It’s hard to avoid the topic of artificial intelligence. Since ChatGPT was introduced in November 2022, AI has infiltrated just about every aspect of human life—and at a pace that is almost impossible to keep up with. Pope Francis recently attended the G7 summit to address global leaders on the perils and promises of AI—the first time a pontiff has ever addressed the G7 summit. Apple just announced that Siri, its voice assistant, is getting updated with generative AI technology. There’s even an AI candidate running for office in the U.K.

AI’s rapid expansion in society has had a profound impact on our education system. Although education technology has been implemented in K-12 schools for decades, this more recent wave involving generative AI has brought significant optimism about how AI can transform education and improve outcomes for the most marginalized students, especially while schools still try to recover from learning loss caused by remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet, many have also expressed grave concerns about the dangers of AI in education, including its potential to exacerbate already persistent inequalities.

Understanding how AI will impact racial disparities in education is critically important to usher in a new generation of technology in schools. This article examines current issues that stakeholders should consider to realize the potential of AI to advance educational equity while also mitigating the risk of bias and discrimination resulting from its usage. Although the topics covered are not exhaustive, we offer some foundational questions and analytical frameworks to help provoke thinking and contribute to the ongoing discussion about race, AI, and education.

What is AI and how has it been used in education?

AI refers to the simulation of human intelligence in machines that are programmed to think and learn like humans. Traditional AI, often called “narrow AI,” includes systems designed to respond to specific sets of tasks via natural language processing and data analysis. Think of voice assistants like Siri or Alexa. According to Bernard Marr, a Forbes contributor, these AIs “have been trained to follow specific rules, do a particular job, and do it well, but they don’t create anything new.” On the other hand, generative AI involves algorithms capable of creating new content, such as text, images, music, and even code, based on massive amounts of data they are trained on. Generative AI includes and is most commonly known for its Large Language Models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT and Google Gemini. Because LLMs are trained on immense amounts of data, they can understand and generate natural language and other types of content to perform a wide range of tasks, such as writing an essay or coding a website.

But what does AI have to do with education? Researchers have actually traced back AI’s application in education to 1970 when Jaime Carbonell, a computer scientist, created a student-facing instructional model called SCHOLAR that “posed or answered questions regarding South American geography and gave instant feedback about the quality of a learner’s responses in natural language.” Present uses of AI in education have built on this foundation, with AI being leveraged primarily to enhance teaching and learning experiences. These tools include but are not limited to:

- Adaptive learning platforms, such as DreamBox and Kidaptive, that use AI to personalize the learning process for students by analyzing their strengths and weaknesses and providing customized educational content;

- AI-driven tutoring systems, like Carnegie Learning’s MATHia and Khanmigo, which offer on-demand assistance and feedback, helping students grasp complex concepts outside the traditional classroom setting; and

- AI-powered writing tools, such as HyperWrite and Grammarly, that assist students in improving their writing skills and provide real-time grammar checks.

However, the integration of AI in education has raised a number of significant issues, particularly regarding its potential to either improve or exacerbate racial disparities.

What are the potential benefits of AI in addressing racial disparities in education?

One potential benefit of AI in education is its ability to personalize learning through adaptive learning systems. Personalized learning may be most impactful for low-income students and students of color, particularly because these students were disproportionately impacted by learning loss due to COVID-19, resulting in a widening of academic achievement gaps. AI can be used to reduce the harmful impacts of these disparities by personalizing learning based on students’ needs. Using machine learning algorithms, AI-enabled adaptive learning systems can analyze student performance data and adjust the difficulty of classroom content based on students’ areas for improvement. These applications of AI tools can improve student information retention, learning outcomes, and teacher capacity.

The Ready to Learn afterschool program offered in urban public schools in Pittsburgh, Pa. is one example of how an AI tool can reduce math achievement gaps for marginalized students. The program uses a Personalized Learning² (PL²) system, a hybrid model that combines human mentoring with AI tutoring, to adapt math content difficulty based on individual student performance. Students using PL² experienced nearly double the gains on standardized math assessments compared to a control group. These findings demonstrate how AI can be used to reduce symptoms of systemic racial inequality and help tailor learning to students’ individual needs.

AI can also help multilingual learners navigate language acquisition with greater ease by providing students with real-time lessons and feedback. At Rancho Milpitas Middle School in Milpitas, Calif. where about 20% of the students are classified as English learners, English Language Arts teacher Victoria Salas Salcedo uses Project Topeka to provide AI-produced feedback and reduce the achievement gap in her classroom. She shared with EdSurge, an education news outlet, that students who often struggle academically in her class “were encouraged because they had immediate, direct feedback that would show them the exact space in their writing where they could improve.” Salas Salcedo described Project Topeka as “almost like having an extra teacher in the room, coaching [students] through the writing process.” This innovative AI application has allowed her to allocate more time to personalized instruction and support for each student.

In addition to advancing student learning through tailored feedback, AI can help accommodate students with disabilities. For example, AI-powered speech-to-text tools, like the application Dictate, can help learners with physical disabilities record written text. Similarly, AI can be used to translate text-to-speech for students who are visually impaired, thereby increasing their access to learning content. The development of more advanced generative AI technology for the classroom, including adaptive technology, is currently underway and has the potential to transform accessibility for all students. However, proper laws and policies to regulate these tools are likely needed particularly because AI algorithms have been known to be discriminatory.

How might AI algorithms exacerbate racial disparities in education?

AI algorithms may exacerbate racial disparities in education when developers input historical data into the technology that replicate pre-existing biases that the model is trained to believe are accurate. For example, predictive analytical tools in education use data, statistical algorithms, and machine learning to help educators support students on their academic and professional journeys. These predictive analytical tools also play a role in determining the likelihood of future student success. Nevada is one of six states where every district uses Infinite Campus, a program that tracks students’ attendance, behavior, and grades to support an “early-warning system” that “employs a machine-learning algorithm to assess the likelihood that each student whose data enters the system will or will not graduate.”

While these tools are intended to assist educators in improving outcomes for students, predictive analytics often rate racial minorities as less likely to succeed academically. This is because race is included as a risk factor in the algorithms and treated as an indicator of success or failure based on the historical performance of students with those identities. For example, an analysis conducted in 2021 found that Wisconsin’s Dropout Early Warning System, which uses race as a data point to predict the likelihood a student will graduate high school on time, generated false alarms about Black and Latino students “at a significantly greater rate than it did for their White classmates.” This false alarm rate, defined as “how frequently a student [the algorithm] predicted wouldn’t graduate on time actually did graduate on time,” was 42% higher for Black students than White students. Instead of clarifying what extra support students need, risk scores tend to have a negative influence on how teachers perceive students and their own beliefs about their academic potential.

Universities are also using algorithms, for example, in the admissions process to determine the likelihood a student is admitted, how much financial aid they should receive, and whether they decide to enroll. Admissions algorithms use a university’s admissions criteria and historical admissions data, comparing them with an applicant’s transcript, essay answers, and even recorded interviews to assist an admissions officer in streamlining admissions decisions, often by sorting applicants into tiers based on their likelihood of admission. Companies such as OneOrigin, Student Select, and Transparency in Education offer algorithmic tools to universities and students that claim to improve efficiency, cut costs, increase admissions yield, and provide transparency to applicants.

However, critics argue that because AI algorithms use historical data to make predictions they are more prone to producing discriminatory outcomes. For example, AI enrollment algorithms use a college’s past applicant data—including high school GPA, standardized test scores, socioeconomic status, zip code, and even how frequently applicants attended college recruitment events—to help determine levels of scholarship funding and the likelihood of enrollment for future students. Although these data inputs are race-neutral and used for a legitimate reason (i.e. predicting the likelihood a student will enroll, which helps with ensuring course availability), the AI tool can nonetheless produce disparate racial impacts. For example, because Black and Latino students have historically scored lower on the math section of the SAT than White and Asian students, the AI algorithm may allocate more scholarship funding to White and Asian students than Black and Latino students.

What are some ethical considerations that may complicate the usage of AI in education?

AI is an emerging technology that presents both great promise and peril for education—a position that raises ethical questions regarding its use. As an emerging technology it is still unclear what AI is fully capable of doing, what future iterations might be like, what new dangers may arise, and how students will interact with it. Yet regardless of the unknown, because AI has the potential to transform education its use will likely continue to expand in U.S. schools.

However, AI’s promise for improving education is complicated by its associated risks. For example, while all schools in a given state may implement similar AI tools in the classroom, wealthier schools may hold an advantage over underfunded ones solely because they can afford to invest in the best AI technologies. In a scenario where wealthy students have access to better AI tools, what if AI does improve academic results for low-income Black students but further boosts results for wealthy White students, widening the academic achievement gap? Should we embrace that outcome because academic results for Black students are nonetheless improving? Or should there be, for example, more careful consideration around AI’s implementation to focus on expanding learning opportunities for students who are most likely to be disadvantaged by AI’s use? And most importantly, are unequal outcomes in AI usage even realistically avoidable given the nature of inequality in the U.S.?

In a scenario where wealthy students have access to better AI tools, what if AI does improve academic results for low-income Black students but further boosts results for wealthy White students, widening the academic achievement gap? Should we embrace that outcome because academic results for Black students are nonetheless improving?

There are also major ethical concerns around student privacy and data collection. AI may accelerate learning for students, but it will also collect, store, and use an enormous amount of data about them. This mass data collection can both threaten students’ privacy and advance existing inequalities. As mentioned above, predictive tasks using student data are susceptible to algorithmic bias and can result in negative outcomes, particularly for low-income students of color. Furthermore, families and students may not be fully aware of what data is being collected, how it will be used, or may never have consented to its use for those purposes. These issues present complications around using student data to propel AI tools intended to improve educational outcomes.

How might the digital divide and AI literacy impact underserved students?

Even with safe AI tools to use, without adequate digital access students will not equally benefit from AI technology. Access to AI underscores the need to ensure students not only have reliable devices and connectivity to the internet—an issue known as the digital divide—but also whether they and their teachers can develop AI literacy, the knowledge and resources needed to understand, use, and evaluate AI.

The digital divide disproportionately impacts students of color, low-income, and rural students. An April 2020 Pew Research Center poll found that nearly half of all parents with lower incomes said they lacked reliable internet connectivity at home and it was likely their children would need to complete school work on a cell phone. A November 2023 Pew Research Center survey found that 72% of White teens had heard about ChatGPT compared to 56% of Black teens. Another study by the Public Policy Institute of California found that in 2021, a staggering 35% of low-income California households still didn’t have reliable internet access. Broadband inequity also persists for rural residents. Researchers have found that 38% of Black residents in the rural south lack broadband access and 43% of Black residents in Mississippi lack access to both broadband and a laptop. Without a device or reliable connectivity, the promise of AI for the nation’s most vulnerable students will unlikely be realized.

Yet, gaining access to a laptop or the Internet is only part of the solution. Even if underserved students have proper infrastructure for AI usage, they often do not have adequate educational resources to support AI literacy, such as a qualified teacher or high-quality curriculum. Without AI literacy, AI tools used by students in under-resourced schools will likely be utilized less effectively than the same tools being utilized by their wealthier counterparts. This discrepancy in AI usage may lead to an expansion of achievement and opportunity gaps in education rather than a closing of those gaps.

Unequal access to AI tools carries enormous consequences for students, including negatively impacting academic performance and undermining career prospects. Limited access also means fewer students from underrepresented backgrounds entering professions in a future workforce where AI competency will be increasingly important for employment and economic mobility.

How does the rapidly evolving nature of AI impact its regulation?

AI has rapidly evolved since ChatGPT became available—and there’s no indication that AI’s development is slowing down. Yet, while proper regulation may help address AI’s issues, passing AI legislation is no easy feat. AI’s nature to quickly change complicates regulatory efforts because regulations may find it difficult to keep pace and run the risk of regulating issues just as technological advances make them no longer controversial. Congress has yet to pass any AI legislation for this very reason. The lack of progress at the federal level has prompted states to take the lead in moving AI policy efforts forward.

In May, Colorado enacted what may be the first comprehensive U.S. state regulation of AI, the Artificial Intelligence Act, which requires “developers” and “deployers” to use “reasonable care to avoid algorithmic discrimination in high-risk artificial intelligence systems.” These “high-risk AI systems” are defined as “those that when used make or are a substantial factor in making ‘consequential’ decisions,” such as those affecting employment or employment opportunity, education enrollment or opportunity, and financial or lending services. More recently, California lawmakers advanced around 30 bills on AI to protect consumers and jobs—one of the largest efforts to regulate AI in the nation. The California legislature is expected to vote on these proposals by August 31.

In October 2022, the White House released the Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights, which identifies five principles that “should guide the design, use, and deployment of automated systems to protect the American public in the age of artificial intelligence.” These five principles include protections against algorithmic discrimination, bolstering data privacy, and building safe and effective systems. Utilizing principles from the Blueprint, in May 2023 the Office of Educational Technology in the U.S. Department of Education released a report, “Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Teaching and Learning,” which synthesizes extensive feedback from education stakeholders that combined with existing research form recommendations for how to advance AI education policy. Further building on the Blueprint, in October 2023, President Biden issued the Executive Order on the Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence—which “establishes new standards for AI safety and security.”

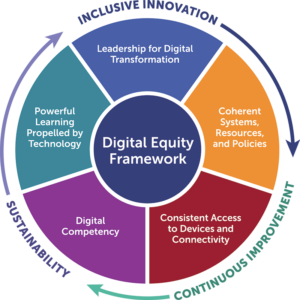

Digital Promise, a global nonprofit working to expand opportunities for all learners, recently released a Digital Equity Framework that offers a systems approach to implementing technology in education, and specifically has implications for AI usage. The Digital Equity Framework prioritizes five key domains designed to address the digital divide, create strong systems that safeguard against risks, and help realize the opportunities presented by emerging technologies like AI. The framework domains include having coherent systems, resources and policies, providing consistent access to devices and connectivity, and building digital competency. Frameworks that take a comprehensive and systems-level approach to using AI can help support education policy at all levels of government.

There also remains an open question as to what responsibility tech companies should have in regulating and ensuring the ethical development of their own AI programs. On one end, because tech companies produce AI tools for public consumption they should bear some responsibility for regulating it. Yet on the other end, it is unclear whether profit-driven companies can be trusted to ethically regulate a technology that is key to their business growth. Should AI regulations come from those who stand to benefit from weak policies?

To date, several leading companies—including Microsoft, OpenAI, and Google—have made an effort to self-regulate by launching the Frontier Model Forum, a “group that promises to work on establishing best practices for the industry and researching AI safety.” Whether they’ve shaped meaningful AI regulations is still to be determined, but most recently they launched the AI Safety Fund, which supports research grants to “address some of the most critical safety risks associated with the proliferated use” of the most cutting-edge generative AI models, like ChatGPT-4.

What should be done now about the usage of AI in education?

As AI usage in education expands, stakeholders should consider how AI tools can become more accessible, particularly in rural and urban communities that have larger populations of low-income students and students of color. Several organizations are already working to address AI access issues. For example, the Stanford Classroom-Ready Resources About AI For Teaching (CRAFT) is a co-design initiative combining the expertise of high school teachers with Stanford researchers and students to provide “free AI Literacy resources about AI for high school teachers, to help students explore, understand, question, and critique AI.” Programs like these can be particularly impactful for communities where technology access is especially low, such as the rural south.

Additionally, because AI can replicate biases based on the data it is trained on (e.g. SAT scores), AI developers should consider who is part of building their AI tools. For programs that aim to improve teaching and learning in K-12 schools, teachers, students, administrators, and families can serve as consultants and collaborators in the development of those AI technologies. Teachers and students provide important contextual information—like whether some activities are small group rather than whole or how neurodiversity affects student learning—that can combat bias in existing predictive algorithms and produce more successful individualized results for diverse students.

Ultimately, the rapid advancement of AI technology commands an urgent need for the U.S. education system to realize the vast potential of AI to address seemingly intractable racial disparities in education—which has serious implications for our future economy. Likewise, the usage of AI in education cannot ignore its tendency to perpetuate bias and discrimination. AI remains a very complex, nuanced, and interconnected issue that leaders in and outside of education should prioritize deeper learning and engagement with. Government, civil society, and tech companies nonetheless have the responsibility to develop AI regulations to ensure its safe and ethical implementation. In an industry where innovation is paramount and technological advances abundant, the sky should be the limit when it comes to advancing educational equity in the era of AI.

Hoang Pham is the Director of Education and Opportunity at the Stanford Center for Racial Justice.

Tanvi Kohli (JD ’26) is a Research Assistant at the Stanford Center for Racial Justice interested in international human rights and environmental justice.

Emily Olick Llano (MA ’24) is a Summer Fellow at the Stanford Center for Racial Justice interested in the intersection of immigration, post-secondary access, and policy.

Imani Nokuri (JD ’25) is a Research Assistant at the Stanford Center for Racial Justice interested in the intersections of race and technology.

Anya Weinstock (JD ’24) was an Advanced Clinic student in the Stanford International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution Clinic and is interested in international human rights and technology law and policy.

Parts of this article were adapted from a memorandum the Stanford Center for Racial Justice and the Stanford International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution Clinic authored for the UN Special Rapporteur on Contemporary Forms of Racism providing analysis about AI and racial discrimination in education for her forthcoming thematic report to the UN General Assembly and Human Rights Council. That memo included student contributions from Bojan Srbinovski, Masha Miura, Imani Nokuri, Roshan Natarajan, Emily Olick Llano, Isabelle Coloma, Tanvi Kohli, Maya King, Anya Weinstock, and Michelle Shim.

Follow the Stanford Center for Racial Justice on LinkedIn and Instagram. Subscribe to the Racial Justice Weekly digest and our monthly newsletter.