The CEQ has No Clothes: The End of CEQ’s NEPA Regulations and the Future of NEPA Practice

On February 20, 2025, the White House Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) posted a pre-publication notice on its website of an Interim Final Rule that rescinds its regulations implementing the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), which, in one form or another, have guided NEPA practice since 1978. CEQ simultaneously issued new guidance to federal agencies for revising their NEPA implementing procedures consistent with the NEPA statute and President Trump’s Executive Order 14,154 (Unleashing American Energy). The Interim Final Rule was submitted for publication in the Federal Register on February 19, 2025 and will become effective 45 days after it is published. This action represents the final blow to CEQ’s NEPA regulations, coming in the wake of two recent federal court decisions in the past few months that foreshadowed their impending demise. In light of those court decisions, CEQ is unlikely to issue new regulations, even under a future presidential administration, without express congressional authorization.

Background

NEPA generally applies to discretionary actions involving federal agencies, including projects carried out by a federal agency itself or by private parties that receive a permit or financial assistance from a federal agency. When NEPA is triggered, it requires a federal agency to analyze the environmental impacts of the project before making a decision to carry it out or issue an approval that may also include conditions or mitigation requirements. NEPA is a procedural law and does not mandate a specific outcome or require that the project proponent mitigate any identified environmental impacts.

NEPA, which was enacted in 1970, is a rather barebones statute. NEPA practice has long been governed by CEQ’s NEPA regulations, which were first promulgated in 1978 after President Carter issued Executive Order 11,991 (Relating to Protection and Enhancement of Environmental Quality) earlier that year directing CEQ to replace its earlier nonbinding guidance. Many common features of NEPA practice — such as environmental assessments, categorical exclusions, programmatic environmental documents, supplemental environmental documents, lead and cooperating agencies, required analysis of a no-action alternative, and required analysis of mitigation measures — are directly tied to CEQ’s 1978 NEPA regulations (some were eventually codified by Congress’s 2023 amendments to NEPA). Agencies could also develop their own NEPA implementing procedures consistent with CEQ’s regulations. Except for one relatively minor amendment in 1986, CEQ’s NEPA regulations did not change between 1978 and 2020, and a large body of case law resulted as courts evaluated agencies’ compliance with the regulations. CEQ substantially revised its regulations during the first Trump administration (in 2020) and during the Biden administration (in 2021 and 2024). For the past nearly 50 years, federal agencies, courts (including the Supreme Court), and NEPA practitioners have largely accepted CEQ’s authority to issue binding regulations without objection.

Recent Court Decisions

Two recent federal court cases challenged the longstanding assumption of CEQ’s authority. First, as we previously reported, in November 2024 the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit found that CEQ lacked authority to issue binding regulations. (Marin Audubon Society v. Federal Aviation Administration, No. 23-1067 (D.C. Cir. Nov. 12, 2024).) On January 31, the full D.C. Circuit denied a petition for rehearing en banc, with a majority of the judges issuing a concurring statement explaining that the earlier decision’s “rejection of the CEQ’s authority to issue binding NEPA regulations was unnecessary to the panel’s disposition” and, impliedly, not part of the court’s holding.

Then, on February 3, in a different case, a federal district court in North Dakota issued a decision expressly holding that CEQ lacked authority to issue binding regulations. (Iowa v. CEQ, No. 1:24-cv-00089 (D.N.D. Feb. 3, 2025).) That case was brought by Iowa and a coalition of 20 other states to challenge CEQ’s regulations issued in May 2024. The court’s decision closely followed the D.C. Circuit’s analysis in Marin Audubon and came to the same conclusion: CEQ does not (and never did) have the authority to issue binding regulations. The court reasoned that CEQ, which was established by NEPA, was authorized by statute only to “make recommendations to the President.” Thus, based on constitutional separation-of-powers principles, President Carter’s 1978 Executive Order could not legally confer regulatory authority on CEQ in the absence of congressional authorization.

Because the court found that CEQ had no regulatory authority, it vacated the challenged 2024 regulations. Notably, although the court’s conclusion about CEQ authority supported vacatur of all CEQ NEPA regulations, it vacated only the 2024 regulations that were challenged in the case before it, leaving “the version of NEPA in place on June 30, 2024, the day before the rule took effect.” The court noted, however, that “it is very likely that if the CEQ has no authority to promulgate the 2024 Rule, it had no authority for the 2020 Rule or the 1978 Rule and the last valid guidelines from CEQ were those set out under President Nixon.”

The court concluded: “The first step to fixing a problem is admitting you have one. The truth is that for the past forty years all three branches of government operated under the erroneous assumption that CEQ had authority. But now everyone knows the state of the emperor’s clothing and it is something we cannot unsee. . . . If Congress wants CEQ to issue regulations, it needs to go through the formal process and grant CEQ the authority to do so.”

CEQ’s Recission of its NEPA Regulations

Meanwhile, CEQ’s NEPA regulations were concurrently under fire from the executive branch. On January 20, President Trump issued Executive Order 14,154 (Unleashing American Energy), which was largely targeted at removing perceived barriers to domestic fossil fuel production and mining, including federal environmental permitting processes. To that end, Section 5 of the Executive Order revoked President Carter’s 1978 Executive Order directing CEQ to issue binding regulations and directed the chairperson of CEQ to, by February 19, (1) propose rescinding all CEQ NEPA regulations and (2) issue new guidance to federal agencies for implementing NEPA. CEQ has now done as directed.

The Interim Final Rule proposes to rescind the entirety of CEQ’s regulations. It will go into effect 45 days after it is published in the Federal Register to give the public an opportunity to submit comments, which CEQ will “consider and respond to” prior to finalizing the rule. In the preamble to the Interim Final Rule, CEQ states it has “concluded that it may lack authority to issue binding rules on agencies in the absence of the now-rescinded E.O. 11191.” While CEQ considers the revocation of the Carter Executive Order to constitute an “independent and sufficient reason” for rescinding the NEPA regulations, it also agrees (contrary to its longstanding and customary practice) that “the plain text of NEPA itself may not directly grant CEQ the power to issue regulations binding upon executive agencies.”

CEQ Guidance to Federal Agencies Regarding NEPA Implementation

At the same time CEQ proposed to rescind its NEPA regulations, it also issued guidance to federal agencies for implementing NEPA going forward and for revising or establishing their own NEPA-implementing procedures, consistent with the NEPA statute and Executive Order 14,154. That guidance recommends agencies “continue to follow their existing practices and procedures for implementing NEPA” while they work on their new procedures and “should not delay pending or ongoing NEPA analyses while undertaking these revisions.” As to these pending or ongoing NEPA reviews, CEQ advises agencies to “apply their current NEPA implementing procedures” and “consider voluntarily relying on” the soon-to-be rescinded regulations.

The guidance also proposes a path forward to agencies to follow in drafting new procedures. It “encourages agencies” to use the 2020 NEPA regulation revisions as a framework and advises that agencies should consider the following:

Prioritize project-sponsor-prepared environmental documents for expeditious review.

Ensure that the statutory timelines established in section 107 of NEPA will be met for completing environmental reviews. (Generally, one year for a completion of an environmental assessment and two years for an environmental impact statement.)

Include an analysis of any adverse environmental effects of not implementing the proposed action in the analysis of a no action alternative to the extent that a no action alternative is feasible.

Analyze the reasonably foreseeable effects of the proposed action consistent with section 102 of NEPA, which does not employ the term “cumulative effects.”

Define agency actions with “no or minimal federal funding” or that involve “loans, loan guarantees, or other forms of financial assistance” where the agency does not exercise sufficient control over the subsequent use of such financial assistance or the effect of the action to not qualify as “major Federal actions.”

Not include an environmental justice analysis, since Executive Order 12,898, which required all federal agencies to “make achieving environmental justice part of its mission” was separately revoked by Executive Order 14,173.

CEQ has set a 12-month timeframe for federal agencies to complete the revision of their NEPA procedures. Agencies must consult with CEQ while revising their implementation procedures and CEQ will hold monthly meetings of the “Federal Agency NEPA Contacts and the NEPA Implementation Working Group” as required by Executive Order 14,154 to coordinate revisions amongst the agencies. Within 30 days of the guidance memorandum, agencies must develop and submit to CEQ a proposed schedule for updating their implementation procedures.

NEPA Practice in the Near Future

Going forward, agencies, project applicants, and NEPA practitioners should rely upon the NEPA statute (as amended by the Fiscal Responsibility Act in 2023) as primary authority. For projects with ongoing or pending NEPA review, applicants should expect federal agencies to continue to apply their existing NEPA practices and rely on the soon-to-be rescinded regulations, except to the extent they are inconsistent with Executive Order 15,154 or the NEPA statute (and in that regard, they will need to be closely evaluated on an individual basis). Case law also will need to be closely analyzed to determine whether courts’ holdings in prior cases were predicated on the statute itself (and therefore, still have binding or persuasive authority, depending on the court) or were based on CEQ’s regulations (in which case they should no longer have any authority). CEQ’s guidance is expressly non-binding, but should also be considered.

In a twist of irony, the rescission of CEQ’s NEPA regulations could lead to greater delays in environmental reviews and permitting (including for fossil fuel production and mining projects favored by Executive Order 14,514), at least in the near term. CEQ’s regulations created uniform procedures that applied to all federal agencies, which was particularly helpful for complex projects that require approvals from multiple federal agencies. Without uniform regulations, each individual agency might now impose its own requirements on the NEPA process. This could result in greater challenges coordinating environmental reviews and permitting among multiple agencies, although CEQ will likely attempt to harmonize implementation procedures as it reviews agencies’ proposals. In addition, permitting delays are expected as agency staff adjust to the new landscape and determine how to comply with NEPA without reliance upon CEQ’s regulations. Staffing shortages resulting from the Trump administration’s efforts to reshape the federal workforce are also likely to additionally exacerbate these problems.

Relatedly, this term, the Supreme Court is considering its first NEPA case since 2004 (Seven County Infrastructure Coalition v. Eagle County) involving the scope of impacts that agencies must consider. Because the case involves the NEPA statute rather than its implementing regulations, the rescission of CEQ’s regulations is unlikely to affect the decision. Oral argument was held in December, and a decision is expected this spring. We will continue to track developments related to this decision.

D.C. Court Finds A Piggyback Statute Of Limitations In Segway-Crash Case

According to court filings, on October 11, 2019, a Segway struck Marilyn Kubichek and Dorothy Baldwin as they strolled along a D.C. sidewalk.

On December 20, 2022, they filed two complaints in the Superior Court based on the Segway incident – one against the operator of the Segway that they said hit them, and one against the tour organizer. The cases were consolidated into one proceeding, Kubichek et al. v. Unlimited Biking et al.

Unfortunately for Ms. Kubichek and Ms. Baldwin, the statute of limitations for negligence in D.C. is three years. Their claims had become untimely before they filed their complaints.

Defendant Eduardo Samonte asserted the statute of limitations in a motion to dismiss, which was granted.

In fact, the order granting Mr. Samonte’s motion actually dismissed the case against both defendants. But the other defendant, Unlimited Biking, had not asserted the statute of limitations.

The question for the Court of Appeals was whether the complaint against Unlimited Biking could be dismissed based on Mr. Samonte’s motion.

Generally speaking, it’s on a defendant to assert the statute of limitations as a defense to the claims against it. Courts don’t do that on their own, and a defendant that fails to assert the statute in its answer to the complaint, or in a motion to dismiss, typically waives the defense.

The Court of Appeals returned to a 1993 case called Feldman, which had suggested that a trial court might have the power to invoke the statute-of-limitations defense on its own, but only if it “is clear from the face of the complaint” that the statutory period has expired.

In the Kubichek case, the Court of Appeals found that it was not clear from the complaints that the statute of limitations had expired.

So – back to court for Unlimited Biking, right?

Not so fast. The Court of Appeals proceeded to fashion a new, “narrow exception” whereby the dismissal of the complaint against Unlimited Biking could be affirmed.

The rule used by the Court appears to work this way:

One defendant asserts the statute of limitations.

+

The plaintiffs have a chance to litigate the issue.

+

The facts relevant to the application of the statute of limitations are not disputed.

+

The relevant facts are the same with respect to both defendants.

=

The trial court may dismiss claims against a defendant that did not assert the statute of limitations.

No litigator or party should neglect to assert a statute-of-limitations defense at the earliest opportunity in a case where the defense may apply. But, after Kubichek, if you are so neglectful, your co-defendant may save you.

Just one more reason why persons who have been harmed and believe they have legal claims should be careful not to wait too long to go to court.

Governor Whitmer Signs New Minimum Wage Law

On February 21, 2025, Governor Gretchen Whitmer signed legislation that preserves Michigan’s tip credit and scales back an increase to the state’s minimum wage. On Wednesday, February 19, 2025, just days before this legislation and the new Earned Sick Time Act (ESTA) were set to take effect, amendments to the minimum wage law received final approval from both the House and Senate. As a result, this afternoon, Governor Whitmer signed both pieces of legislation into law. For more information about changes to ESTA, see Varnum’s advisory here.

Under the amendments to the minimum wage law, the new minimum hourly wage rate is:

Hourly Rate

Effective Date

$12.48

February 21, 2025

$13.73

January 1, 2026

$15.00

January 1, 2027

The new minimum hourly wage rate for tipped employees is:

Hourly Wage Rate

Effective Date

38% of the minimum hourly wage rate

February 21, 2025

40% of the minimum hourly wage rate

January 1, 2026

42% of the minimum hourly wage rate

January 1, 2027

44% of the minimum hourly wage rate

January 1, 2028

46% of the minimum hourly wage rate

January 1, 2029

48% of the minimum hourly wage rate

January 1, 2030

50% of the minimum hourly wage rate

January 1, 2031

The bill also stipulates that beginning in October 2027, the state’s minimum wage must increase based on the rate of inflation. The state treasurer will calculate the increase by multiplying the otherwise applicable minimum wage by the 12-month percentage increase, if any, in the Consumer Price Index for the Midwest region, CPI-U or a successor index as published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Additionally, the bill transfers oversight from the Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs to the Department of Labor and Economic Opportunity. It also subjects employers to a civil fine of no more than $2,500 for failing to pay the minimum hourly wage to employees who receive gratuities in the course of their employment.

Additional Authors: Luis E. Avila, Francesca L. Parnham, and Carolyn M.H. Sullivan

No Business Transaction, No Chapter 93A Claim: Mass. Courts Clarify Requirements

To pursue a Chapter 93A claim, there must be some business, commercial, or transactional relationship between the plaintiff(s) and the defendant(s). An indirect commercial link—such as upstream purchasers—may be sufficient to state a valid claim, but there must ultimately be some commercial connection between the plaintiff and defendant. The District of Massachusetts and the Appeals Court of Massachusetts recently affirmed this requirement in two separate cases.

First, the District of Massachusetts affirmed this principle when it denied plaintiffs’ motion for leave to conduct limited discovery, as the allegations in the complaint only highlighted the commercial relationship between the various defendants and not with the plaintiff. In Courtemanche v. Motorola Sols., Inc., plaintiffs brought a putative class action against a group of commercial defendants and the superintendent of Massachusetts State Police, alleging that the State Police unlawfully recorded conversation content between officers and plaintiffs, and then later used those recordings to pursue criminal charges against plaintiffs. The commercial defendants allegedly willfully assisted the State Police by providing them with intercepting devices and storing the recordings on their servers. The commercial defendants moved to dismiss based on plaintiffs’ failure to allege a business, commercial, or transactional relationship between them and the commercial defendants. Plaintiffs then sought to conduct limited discovery in order to establish such a relationship. The court concluded that allowing even limited discovery on the issue would only amount to an inappropriate fishing expedition and denied the motion.

Shortly thereafter, the Massachusetts Appeals Court reversed portions of a consolidated judgment against defendants for Chapter 93A § 11 violations in Flightlevel Norwood, LLC v. Boston Executive Helicopters, LLC. On appeal, the defendants argued, and the Appeals Court agreed, that the trial judge erred in denying their motion for judgment notwithstanding the verdict. The parties both operated businesses at the Norwood Memorial Airport and subleased adjoining parcels of land with a taxiway running along their common border. At trial, plaintiff argued that defendants engaged in unfair acts to exercise dominion and control over plaintiff’s leasehold to advance defendants’ commercial interests and deliberately interfere with plaintiff’s commercial operations. The Appeals Court reiterated that to maintain a Section 11 claim, a business needs to show more than just being harmed by another business’s unfair practices. Instead, plaintiff must prove that it had a significant business deal with the other company, and that the unfair practices occurred as part of the deal. The Appeals Court thus concluded that Chapter 93A § 11 was inapplicable, as there was no business transaction between the parties.

March 14, 2025, Looming as Important Date for Congressional Republicans and President Trump, and May Provide Leverage to Democrats

March 14, 2025, looms as an important deadline in the middle of President Trump’s first 100 days in office, a milestone often used to evaluate the effectiveness of a new President. March 14 is the day that the American Relief Act, 2025 (Public Law 118-158), which provides temporary funding for the federal government, expires. The law was enacted during the 118th Congress and signed into law by President Biden. At the time, some questioned whether having government funding expire during President Trump’s first 100 days in office was a good idea. Now, Republicans, who control the White House, Senate, and House of Representatives, need to pass legislation to avoid a government shutdown on March 15, and may need Democratic support to do so. The question is, at what cost?

Government funding is not the only thing that expires March 14, 2025. The National Flood Insurance Program was extended through March 14, 2025, and will also expire if not extended, as will Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), which provides benefits to families in need. Congress also needs to raise the debt limit, but not necessarily within this same timeframe.

Simultaneous with figuring out how to fund the federal government for the remainder of Fiscal Year 2025, the Republican-led Congress also is working on legislation to enact President Trump’s priority issues, including extending the 2017 tax provisions, providing money for border security, and addressing immigration. Making matters more challenging, leadership in the House of Representatives and Senate are taking sharply different approaches to developing such legislation. Adding one more degree of difficulty to this legislative effort, House Republicans in the last Congress needed Democrats to vote for the legislation for it to pass. What is unknown this time is whether Democrats will vote in sufficient numbers with Republicans to fund the government and, if so, what concessions they will be able to gain from Republicans to secure their support.

I wrote in December that slim majorities will test Republican unity in the 119th Congress. The looming March 14, 2025, deadline combined with the desire to pass legislation to enact President Trump’s priorities early in 2025, present an interesting test of Republican unity, and may present out-of-power Democrats with sufficient leverage to gain concessions to win their support. The next few weeks will provide a fascinating look at what to expect for the remainder of the 119th Congress.

FDA Continues Push to Improve Food Labeling Practices in the United States

In September 2022, former President Biden convened the White House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health, during which the White House introduced its National Strategy on Nutrition and Health (National Strategy). The National Strategy called for creating more accessible food labeling practices to empower consumers to make healthier choices, among other laudable public health-focused goals. Prior to the January 2025 transition from the Biden to the Trump administration, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) took concrete steps to address this particular National Strategy priority through both formal rulemaking and informal guidance. This blog post summarizes FDA’s actions at the end of the Biden administration intended to modernize food labeling practices and move them forward in today’s more consumer-focused marketplace.

Proposed Rule for Front-of-Package Nutrition Labeling

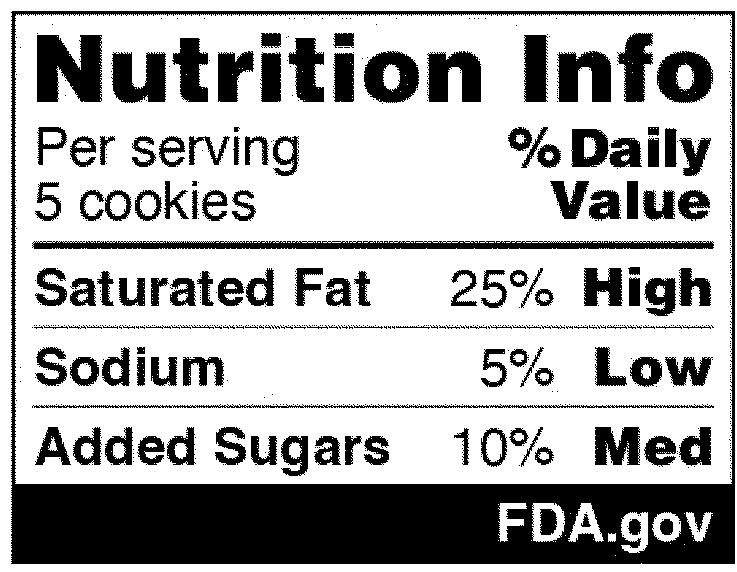

In the National Strategy, the development of front-of-package (FOP) labeling schemes was discussed as one way to promote equitable access to nutrition information and healthier choices. On January 16, 2025, FDA published in the Federal Register a proposed rule that would require a front-of-package nutrition label on packaged foods (Proposed Rule). The Proposed Rule would require manufacturers to add a “Nutrition Info” box on the principal display panel of each packaged food product, which would list the Daily Value (DV) percentage of saturated fat, sodium, and added sugars in a serving of that food. The DV percentage would list how much of the nutrient in a serving contributes to a person’s total daily diet. In addition, each of those nutrients would include corresponding “interpretative information” that would signal to consumers whether the food product contains a low, medium, or high amount of those nutrients. An example of the proposed FOP nutrition information graphic is below. And although the Proposed Rule would not require it, manufacturers could voluntarily include a calorie count on the front of the food package, per existing FDA regulations.

The Proposed Rule does deviate from certain suggestions made in the National Strategy, which advocated for FOP “star ratings” and “traffic light schemes” to promote equitable access to nutrition information. Specifically, the National Strategy considered how to best help consumers with lower nutrition literacy more readily identify foods that comprise a healthy diet. Instead of a front-of-packaging labeling system that would rely on imagery, however, FDA’s proposal opted for written information about the nutrients contained in the food. Both the preamble to the Proposed Rule and FDA’s press release announcing its publication explain that in focus groups conducted in 2022, participants reported confusion over the traffic light system in particular (e.g., when a food contained both nutrients that should be limited but also nutrients for which higher consumption is recommended) and that “the black and white Nutrition Info scheme with the percent [DV] performed best in helping consumers identify healthier food options.”

It will be interesting to see whether comments to the Proposed Rule will remark on FDA’s choice of the written “Nutrition Info” box versus a FOP labeling system that would be more reliant on imagery. FDA is accepting comments on the Proposed Rule until May 16, 2025 (Docket FDA-2024-N-2910). As currently envisioned, if the proposal for FOP nutrition information is adopted, most food product manufacturers would have three years from the effective date to bring labels into compliance (smaller manufacturers would be given four years).

As a result of President Trump’s administrative freeze and new executive orders governing the work of regulatory agencies such as FDA, the fate of this Proposed Rule is currently uncertain. However, newly confirmed Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has articulated that his agenda is to “make America healthy again” (MAHA) and the presidential MAHA Commission was recently established to begin informing the Administration’s work on Mr. Kennedy and President Trump’s priorities in this space. Although Mr. Kennedy did not address food labeling during his Senate confirmation hearings and the executive order creating the MAHA Commission does not speak directly to food labeling or nutrition information accessibility for consumers, interested stakeholders should monitor the upcoming work of the Commission – including whether any opportunities for public comments may be made available – as well as its future “Make Our Children Healthy Again Strategy” that is due in approximately six months. Further, under a deregulatory executive order signed on January 31, 2025, President Trump has directed agencies to eliminate 10 “regulations” for each new regulation to be promulgated, with the term “regulation” expansively defined to include memoranda, guidance documents, policy statements, and interagency agreements. This “one-in, 10-out” order may make the prospect of an FOP nutrition labeling final rule less likely, at least for the foreseeable future.

Final Rule for Use of The Term “Healthy” on Food Labeling

Another recent FDA action related to food labeling was the agency’s finalization of a proposed rule from 2022 that involved a lengthy public consultation and information collection process (see our prior coverage here). On December 27, 2024, FDA published in the Federal Register its Final Rule regarding the use of the term “healthy” in food labeling. The Final Rule updates the definition established 30 years ago for the nutrient content claim “healthy” to be used in food labeling. In President Biden’s National Strategy, one highlighted priority was ensuring that food packages bearing this claim align with current nutrition science and the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (Dietary Guidelines). To advance this goal, FDA was charged with updating the standards for when a company can use the “healthy” claim on its products (work on which was already ongoing at the agency), creating a symbol that can be used to reflect that the food is “healthy, and developing guidance on the use of Dietary Guideline statements on food labels.

The original regulatory definition of “healthy” (codified at 21 C.F.R. § 101.65(d)) sets limits on total fat, saturated fat, cholesterol, and sodium content should a food be labeled as healthy, and requires that the food contain at least 10% of the DV for vitamin A, vitamin C, calcium, iron, protein, and fiber. Under the Final Rule, total fat and dietary cholesterol are no longer factors to be considered when evaluating whether a food is eligible for this particular nutrient content claim. Instead, the agency has established limits on saturated fat, sodium, and added sugars in accordance with the Dietary Guidelines. Additionally, rather than focusing on vitamin A, vitamin C, calcium, iron, protein, and fiber, the Final Rule requires that the food product contain a certain amount of food from at least one of the food groups or subgroups recommended by the Dietary Guidelines, such as fruit, vegetables, grains, dairy, and proteins.

Perhaps most notably, the prior regulatory scheme allowed for foods that were high in added sugars, such as yogurts, breakfast cereals, and fruit snacks, to technically qualify as “healthy” despite not aligning with the definition of “nutrient-dense” foods from the Dietary Guidelines, which specifically applies to certain foods “when prepared with no or little added sugars, saturated fat, and sodium.” Consistent with generally accepted nutritional best practices, the National Strategy also promoted lowering the sodium content in food and decreasing the consumption of added sugars –shared goals of new HHS Secretary Kennedy and the broader MAHA agenda.

The Final Rule does not establish a “healthy” symbol that can be used on food packaging, but FDA has indicated that this symbol may also be on the horizon. In its press release announcing the Final Rule, FDA noted that it is “continuing to develop” this symbol, adding that such a symbol would further FDA’s goal of helping consumers more easily identify healthier food products.

The Final Rule’s effective date (which as of publication of this blog post, has not been changed by the Trump Administration) is February 25, 2025, and the compliance date for manufacturers is February 25, 2028 – three years after the new regulatory definition becomes effective.

Draft Guidance for Industry: Labeling of Plant-Based Alternatives to Animal-Derived Foods

Finally, while not specifically called out in the National Strategy, FDA has been working for several years to develop labeling recommendations for plant-based foods that are being developed and marketed as alternatives to conventional animal products. On January 7, 2025, FDA released the Draft Guidance for the Labeling of Plant-Based Alternatives to Animal Derived Foods (Draft Guidance), in response to the growing demand for plant-based food alternatives in the United States. According to the Plant-Based Food Association, 70% of Americans are consuming plant-based foods. The scope of the newly released guidance encompasses alternatives to poultry, meat, seafood, and dairy products that fall under FDA’s jurisdiction. It expressly excludes plant-based milk alternatives, as separate guidance on that subject was released in February 2023.

The Draft Guidance notes that rather than simply identifying a product as a “plant-based” alternative food, the specific plant source should be disclosed on the food product’s label. This would enable consumers to make more informed choices about purchasing plant-based alternatives. For example, rather than labeling a plant-based cheese solely as such, the cheese’s label should more clearly disclose “soy-based cheese” to reflect its primary ingredients. The Draft Guidance also recommends that if a plant-based alternative food is derived from several different plant sources, the primary plant sources should be identified in the food’s name. The agency provides the examples of “Black Bean Mushroom Veggie Patties” and “Chia and Flax Seed Egg-less Scramble” to illustrate this concept. For labeling purposes, FDA also recommends companies avoid exclusively naming products with “vegan,” “meat-free,” or “animal-free.”

Public comments on the Draft Guidance should be submitted by May 7, 2025 (Docket FDA-2022-D-1102).

Conclusion

One primary goal of the National Strategy was to empower Americans to make healthier, informed choices about their nutrition and food consumption. In the United States, diet-related diseases, such as hypertension, obesity, and diabetes, are on the rise. Under the Biden administration and the leadership of former Commissioner Dr. Robert Califf, FDA sought to fight these alarming trends and to improve public health by increasing access to nutritional information and promoting transparency in food labeling.

Further, while the Proposed Rule, Final Rule, and Draft Guidance all focus on labeling packaged food products that can be purchased in stores, it will be interesting to see how these initiatives influence FDA’s recommendations for food labeling practices in online grocery shopping. On April 24, 2023, FDA published the notice Food Labeling in Online Grocery Shopping; Request for Information (Docket No. FDA-2023-N-0624-0002), which received 31 electronically submitted comments from various stakeholders, including grocer organizations, food scientists, and individual consumers. Indeed, the December 2024 press release for the Final Rule noted that FDA “has already entered into a partnership with Instacart to make it even easier for consumers to find products with the ‘healthy’ claim through online grocery shopping filters and a virtual storefront.” In the wake of the agency actions summarized in this post and the Instacart partnership, we wonder if FDA will move in the future to provide manufacturers and retailers with definitive guidance on online food labeling practices. We will be watching to see how FDA, as well as the work of the MAHA Commission and HHS Secretary Kennedy, may continue to improve food labeling practices in the future.

Two Lawsuits Challenge Trump Administration’s Termination of Venezuela TPS

Advocacy groups and Venezuelan immigrants have filed suit in federal courts over terminated removal protections for Venezuelans in the United States.

On Feb. 19, 2025, the National TPS Alliance, an advocacy group for immigrants who have been granted Temporary Protected Status (TPS), and seven Venezuelans living in the United States, filed a lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California challenging the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS’s) decision to terminate Venezuela TPS. The termination impacts approximately 600,000 Venezuelan nationals (350,000 under the 2023 designation and 250,000 under the 2021 designation).

On Feb. 20, 2025, immigrant advocacy groups CASA, Inc. and Make the Road New York filed a lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for the District of Maryland also challenging the termination of Venezuela TPS.

Both suits allege that DHS Secretary Kristi Noem lacked legal authority to vacate former DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas’ Jan. 17, 2025, decision to grant an 18-month extension of TPS for Venezuela.

The suits further contend that even if DHS possessed legal authority to terminate Venezuela TPS, it arbitrarily deviated from prior decisions, incorrectly concluding that Venezuelans granted TPS reside in the United States illegally.

The plaintiffs also allege that Secretary Noem’s decision was motivated by “racial animus,” pointing to an interview she gave to Fox News announcing her Feb. 5, 2025, decision to terminate Venezuela TPS in which she referred to Venezuelans granted TPS as “dirtbags.”

Both suits cite violations of the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) and the Fifth Amendment’s Equal Protection and Substantive Due Process clauses. They ask the courts to declare that former DHS Secretary Mayorkas’ 18-month extension of Venezuela TPS remains in effect and to enjoin enforcement of the Feb. 3, 2025, vacatur and Feb. 5, 2025, termination decisions.

Both suits have the potential to extend the Venezuela TPS designation for individuals who registered under both the 2021 and 2023 designations, as well as the validity of work authorizations based upon Venezuela TPS, while the litigation is pending.

Michigan’s Earned Sick Time Act Amended: Employer Takeaways

On February 20, 2025, Michigan lawmakers voted to amend the Earned Sick Time Act (ESTA) to provide greater clarity and flexibility to both employees and employers with respect to paid time off, taking immediate effect. This action followed earlier votes this week by the Michigan legislature on the minimum wage law. Governor Whitmer has now signed both pieces of legislation into law.

Key changes to ESTA as of February 21, 2025, are as follows:

Employers are expressly permitted to frontload at least 72 hours of paid sick time per year, for immediate use, to satisfy ESTA’s leave requirement. Employers who frontload hours do not need to carry over unused paid sick time year to year and do not have to calculate and track the accrual of paid sick time for full-time employees. For part-time employees, frontloading in lieu of carryover is also an option, including frontloading a prorated number of hours. Employers choosing to frontload a prorated amount must follow notice, award amount, and true-up requirements.

If paid sick time is not frontloaded, employees still must accrue 1 hour of paid sick leave for every 30 hours worked, but employers may cap usage at 72 hours per year. Only 72 hours of unused paid sick time is required to roll over from year to year for employers who provide leave via accrual.

New hires can be required to wait until 120 days of employment before they can use accrued paid sick time, which could potentially benefit seasonal employers. This waiting period appears to be permitted for frontloading and accruing employers alike, although the bill’s language with respect to frontloading employers is somewhat unclear. This may be an issue for clarification by the Department of Labor and Economic Opportunity, which under the amendment will be responsible for all enforcement of the law.

ESTA now provides several exemptions, including:

An individual who follows a policy allowing them to schedule their own hours and prohibits the employer from taking adverse personnel action if the individual does not schedule a minimum number of working hours is no longer an “employee” under ESTA.

Unpaid trainees or unpaid interns are now exempt from ESTA.

Individuals employed in accordance with the Youth Employment Standards Act, MCL 409.101-.124, are also exempt from ESTA.

Small businesses, defined as those with 10 or fewer employees, are only required to provide up to 40 hours of paid earned sick time. The additional 32 hours of unpaid leave, required under the original version of ESTA, is no longer required. Small businesses, like other employers, are permitted to provide leave via a frontload of this entire applicable amount or to provide the time via accrual. If small businesses use the accrual method (1 hour of paid sick time for every 30 hours worked), they may cap paid sick time usage at 40 hours per year and only permit carryover of up to 40 hours of unused paid sick time year to year. Small businesses have until October 1, 2025, to comply with several ESTA requirements, including the accrual or frontloading of paid earned sick time and the calculation and/or tracking of earned sick time.

Employers can now use a single paid time off (PTO) policy to satisfy ESTA. Earned sick time may be combined with other forms of PTO, as long as the amount of paid leave provided meets or exceeds what is otherwise required under ESTA. The paid leave may be used for ESTA purposes or for any other purpose.

The amendments clarify that an employee’s normal hourly rate for ESTA purposes does not include overtime pay, holiday pay, bonuses, commissions, supplemental pay, piece-rate pay, tips or gratuities.

The amendments specify that the Department of Labor and Economic Opportunity is responsible for enforcement of the Act. Prior provisions that included a private right of action for employees to sue their employers for possible ESTA violations have been removed.

The amendments remove a “rebuttable presumption” of retaliation that was contained in the original Act.

ESTA now permits employers to choose between one-hour increments or the smallest increment used to track absences as the minimum increment for using earned sick time.

The amendments allow a means for employers to require compliance with absence reporting guidelines for unforeseeable ESTA use. To do this, an employer must comply with steps outlined in the amendment including disclosure of such requirements to employees in writing.

The amendments specify that employers must provide written notice to employees including specified information about the Act within 30 days of the effective date. This would mean a date of March 23, 2025.

The amendments allow for postponement of the effective date of ESTA for employees covered by a collective bargaining agreement that “conflicts” with the Act. The effective date for such employees is the expiration date of the current collective bargaining agreement.

The amendments likewise allow for the postponement of ESTA’s effective date for employees who are party to existing written employment agreements that “prevent compliance” with the Act. Reliance on such provisions requires notification to the state.

Some provisions of the bill give rise to continuing confusion or ambiguity, including:

The amended law continues to contain a provision requiring the display of a poster from the Department of Labor and Economic Growth, which appears to be effective immediately upon the date the bill is signed into law. However, no updated poster exists.

The statute’s reference to “conflict” between a collective bargaining agreement and ESTA is not well defined, including how this provision will apply to a collective bargaining agreement that, perhaps intentionally through prior negotiations, includes no current provisions for sick time.

Whether the amended law is intended to exclude nonprofit organizations from the scope of covered employers is unclear. The reference to nonprofits was stricken, but there is no affirmative language excluding them from the broad “employer” definition that remains in the law.

The availability of a 120-day waiting period for a frontloading employer is somewhat unclear, due to the provisions that frontloaded time must be “available for immediate use.”

The date employees may first use earned sick time, in relation to the time frame for employers to finalize and issue policies, would benefit from clarification. The amendment states that accrual begins on the effective date of the Act, and time may be used “when it is accrued.” However, employers appear to have a 30-day time frame to finalize and issue policies defining how they choose to provide ESTA’s benefits.

The extent of employer recordkeeping and/or inspection obligations are unclear under the current law. Previous provisions detailing such requirements are no longer included.

Additional Authors: Luis E. Avila, Francesca L. Parnham, and Carolyn M.H. Sullivan

Hold on Tight: Last-Minute Changes to the Earned Sick Time Act

Michigan’s Earned Sick Time Act (ESTA), scheduled to take effect on February 21, 2025, was amended on February 20, 2025, to provide additional clarity and administrative ease. Yesterday, both chambers of the legislature reached an agreement on an amendment to the ESTA, introducing several changes the day before its scheduled effective date. Many employers have been patiently anticipating this amendment—and that anticipation has finally become a reality.

Quick Hits

Michigan Governor Whitmer is expected to sign an amendment to the Earned Sick Time Act, one day before the act’s effective date, providing several employer-friendly changes.

Employers with fewer than ten employees now have until October 1, 2025, to comply.

Highlights of the amendment include clarifications regarding covered employer qualifications, benefit accruals, employee eligibility, and benefit amounts.

Quick History

In 2019, Michigan enacted the Paid Medical Leave Act (PMLA) in response to an adopted ballot initiative that originally called for the ESTA. At that time, employers implemented changes to their paid time-off policies to comply with the PMLA. However, after the PMLA’s implementation, litigation ensued challenging the adopt-and-amend procedure used by the legislature to move from the ESTA to the PMLA. On July 31, 2024, the litigation reached the Michigan Supreme Court, which, in a 4–3 decision, ruled that the adopt-and-amend approach was unconstitutional. The Michigan Supreme Court confirmed that the ESTA should have taken effect and set its implementation date for February 21, 2025. The ESTA represents a vast departure from the PMLA.

Where Are We Now?

Since the Michigan Supreme Court’s decision, Michigan’s lawmakers have been working to amend the ESTA before its implementation date. Down to the wire, that amendment has now passed and takes effect February 21, 2025; however, employers ten or fewer employees have until October 1, 2025, to comply. The amendment makes several employer-friendly changes, provides more clarity on the ESTA’s requirements, and makes the law easier to administer.

While the official amendment contains further changes, here are some highlights:

Provision

PMLA

ESTA

ESTA as Amended on February 20, 2025

Covered Employers

Applies to employers with 50 or more employees (small business exemption).

Applies to employers, but small employers with fewer than 10 employees must provide slightly different benefit. No exemption.

Applies to all employers, but employers with 10 or fewer employees must provide slightly different benefits. Exempts new business start-ups for 3 years.

Benefit Accrual

Explicitly permits frontloading or minimum accrual of 1 hour paid leave for every 35 hours worked.

No frontloading provided explicitly; frontloading employers still need to track accrual and comply with carryover requirements. Minimum accrual of 1 hour paid leave for every 30 hours worked.

Provides for frontloading at the beginning of a year for immediate use. When frontloading is used, employers do not need to calculate and track accrual. Additional written notice requirements when time is frontloaded for part-time employees. Accrual rate remains 1 hour paid leave for every 30 hours worked.

Eligibility

Excludes exempt, seasonal, temporary, and other employees.

Does not exclude any employees. Expands “family member” to include domestic partners (defined in the act) and “any other individual related by blood or affinity whose close association with the employee is equivalent to a family member.”

Excludes (1) employees that can set their own working hours (with conditions), (2) unpaid interns or trainees, and (3) youth employees as defined under the Youth Employment Standards Act. Definition of “family member” eliminates individuals related by affinity, but recognizes individuals in close relationships that are equivalent to a family relationship.

Benefit Amount

40 hours of paid sick leave.

72 hours of paid sick leave. Employers with fewer than 10 employees must provide 40 hours of paid leave and 32 hours of unpaid leave.

72 hours of paid sick leave per year 40 hours of paid sick leave per year for employers with 10 or fewer employees.

Use of Other Paid Time Off

May comply with the act by providing other paid time off available for statutory purposes.

Same/unchanged.

Same/unchanged.

Carryover

Must carry over up to 40 hours if using the accrual method. No carryover for frontloading.

Must carry over any balance (without regard to the method used to award the time).

No carryover if employers choose to frontload. Employers using an accrual method must carry over up to 72 unused hours (40 hours for employers with 10 or fewer employees).

Cap on Use

May cap at 40 hours of use per year.

May cap use at 72 hours per year.

May cap use at 72 hours per year. Employers with 10 or fewer employees may cap use at 40 hours per year.

Increment of Use

The employer may set the increment.

The smaller of 1 hour or the smallest increment of time the employer uses to track other absences.

Either 1-hour increments or the smallest increment the employer uses to account for absences of use of other time.

Supporting Documentation

If requested, employees must provide within 3 days.

Can only be requested if the employee is absent for more than 3 consecutive days. If requested, the employee must provide in a “timely manner,” and the employer must pay for any out-of-pocket expenses incurred in obtaining the documentation.

Same/unchanged—requires employees to provide documentation within 15 days.

Retaliation

No specific prohibition on retaliation.

Prohibits retaliation with a rebuttable resumption of retaliation, if adverse action is taken against an employee within 90 days of certain activity protected by the act.

No rebuttable presumption of retaliation. Adverse personnel action may be taken against an employee for using earned sick time for a purpose other than that provided in the act or if the employee violates the notice requirements of the act.

Remedies

Administrative complaint only. Must be filed within 6 months. No private cause of action.

Provides a private cause of action with no administrative exhaustion requirement. Can still file an administrative complaint. 3-year statute of limitations on private action.

Administrative complaint only. No private cause of action. 3-year statute of limitations.

Effect on Collective Bargaining Agreements (CBAs)

Did not override a CBA then in effect. Subsequent CBAs need to comply.

Same/unchanged.

Same/unchanged. Also provides a similar exception for certain employment contracts.

Waiting Period

Employers may require employees to wait 90 days after hire to use their sick time.

Employers may require an employee hired after the effective date to wait until the 120th calendar day after hire to use accrued sick time.

Calculation

Earned sick time is paid at the employee’s normal hourly wage.

Clarifies that the rate of pay does not include overtime, holiday pay, bonuses, commissions, supplemental pay, piece rate pay, tips or gratuities in the calculation.

Effect on Termination, Transfer, and Rehire

The employer must reinstate any unused sick time if rehired within 6 months of separation.

The employer must reinstate any unused sick time if rehired within 2 months of separation unless the value of the sick pay was paid out at time of termination or transfer.

Employee Notice

Rely on usual and customary rules.

The employer may create a policy on requesting sick leave if the employer provides the employee a copy of the written policy and the policy allows the employee to provide notice after the employee is aware of the need for earned sick time.

Employer Notice

Written notice must be provided to an employee at the time of hire or not later than 30 days after the effective date of the amendatory act, whichever is later, including: the amount of earned sick time to be provided; the employer’s choice of how to calculate the year; the terms under which sick time may be used, retaliatory personnel action is prohibited; and the employee’s right to file an administrative complaint.

These changes will likely be welcomed by many employers. Employers can now confidently adjust and administer their existing paid time-off policies to comply with the amended ESTA.

Navigating the EPR Laws: What Alcohol Beverage Producers Need to Know

Extended producer responsibility (EPR) laws are relatively new – the first were signed into law in 2021 and 2022 – and are aimed at encouraging producers to package goods in a more environmentally conscientious manner and providing much needed revenue for in-state recyclers overwhelmed by the incoming volumes of recyclable material. In essence, EPR laws require producers whose products reach in-state consumers to register with a producer responsibility organization (PRO) or stewardship organization (SO), report the amount of material that enters the state, and pay fees for that material.

As detailed in this article, how and if these new laws apply to alcohol beverage suppliers is nuanced given both the developing nature of EPR laws as well as the interplay with preexisting container deposit or bottle bill laws.

Who and What Is Covered by the New EPR Laws?

As of the writing of this article, five states have passed EPR laws and 10 others have introduced bills during their most recent legislative sessions, including Connecticut, Hawaii, Nebraska, and New York. EPR programs are still evolving as the various regulatory processes continue; however, once passed by a state, the new rules typically require the state to designate a PRO/SO to administer the producer requirements and aid producers and state agencies with the necessary reporting and payment requirements. For those states that have passed EPR laws, the nonprofit organization Circular Action Alliance is the PRO/SO that has been selected to oversee the process.

Each EPR law has its own definition of “producer” (i.e., those required to report) and of “covered material” (i.e., the materials that must be reported). There are several specifics within each state but, generally, the producer is the entity who actually produces the subject goods or the owner of the brand that is contracting to have the item produced. Speaking broadly, the covered material contemplated by these laws includes the cardboard boxes and glass or aluminum containers that protect and contain the items purchased from retailers. In this regard, EPR laws apply to alcoholic beverages, non-alcoholic beverages, and nearly all other types of consumer goods.

However, exemptions exist for small producers and certain materials. The specifics as to when a producer is exempt from registering and making EPR payments vary by state but, in many instances, those producers shipping small amounts into a certain state will be exempt. For example, Minnesota exempts producers responsible for less than one metric ton of covered material or $2,000,000 in global gross revenue. However, it is important to remember that even if a small producer is, given its status, exempt from registering with a PRO/SO or paying the related EPR fees, it will likely still have reporting requirements to substantiate its claims of being exempt.

How Do These Laws Apply and Interface with Alcohol Beverage Laws?

In the world of beverage alcohol, there are numerous laws already in place, many of which have been in force for decades, that are aimed at sustainability and designed to fund and encourage recycling. These are referred to as beverage container deposit/recycling deposit requirements or “bottle bills.” These laws generally require subject beverages to have, listed on their labels, their deposit amount or to otherwise identify the bottle as one that is subject to deposit requirements. They also require a small deposit to be paid by the retailer and/or by the consumer for the purchase of subject beverages, only refunding the deposit to the consumer when the bottle is returned and requiring a reimbursement and handling fee to be paid by distributors and/or manufacturers for the processing/recycling of the containers.

The exact recycling model, deposit collection, and payment process varies by state. For instance, California does not require the amount of the deposit to be listed on the bottles and requires the distributor and the manufacturer/importer to remit payments, but it does not require the retailer to submit payments, as the retailers are generally acting as the redemption centers for consumers.

Fortunately, many of the EPR laws specifically exempt items subject to beverage container deposit requirements. However, the interplay between the older beverage container deposit requirements and the newer EPR laws are not always straightforward. For example, in Oregon, “beverage containers” as defined by the recycling deposit regulations are excluded from the definition of “covered products” (i.e., those subject to EPR requirements). But only “water or flavored water; beer or another malt beverage; mineral water, soda water, or a similar carbonated soft drink; kombucha; or hard seltzer” are subject to deposit regulation, not wine or spirits. This means, for a producer that is selling wine, spirits, and malt beverages into Oregon, while they would be able to exclude the weight of the cases for the malt beverages (malt cans/bottles would be exempt), they would still have to calculate the weight of the bottles and cases for the wine and spirits when reporting.

In short, given the developing nature of these laws, coupled with the nuances of their interplay with other alcohol beverage-specific requirements, there is no one-size-fits-all analysis as to how and when these laws apply to alcohol beverage producers. There are some instances where an alcohol-specific exemption may apply and other states where no such exemption exists. To ensure compliance in this rapidly evolving landscape, each company’s business structure must be examined carefully to determine whether it, or the products it ships, are subject to EPR laws, bottle bills, or both.

Navigating Changes at the USPTO: Impact of New Government Cost-Reduction Initiatives

The new presidential Administration’s cost-reduction initiatives, including a hiring freeze and return-to-office mandate for federal employees, are poised to impact the efficiency of the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), potentially affecting patent examination timelines and strategies.

The new presidential Administration’s focus on reducing government spending has resulted in a number of cost reducing initiatives, including several that have a direct effect on the USPTO. These initiatives include implementing a hiring freeze across the federal government and a return to office mandate coupled with a buyout option for federal employees. The hiring freeze has resulted in a cancellation of USPTO job advertisements and rescinded offers of employment to new patent examiners, while the return to office mandate coupled with a buyout option for federal employees has the potential to affect a significant number of USPTO employees, including many senior examiners and Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) judges. Moreover, the recent resignation of Commissioner for Patents, Vaishali Udupa, is sure to affect the course and policies of the USPTO as it navigates these significant changes.

These changes are likely to affect the efficiency and speed of patent examinations, appeals, and trials at the PTAB, and could increase pendency of applications and other matters under the purview of the USPTO. Our Intellectual Property (IP) practice group at AFS understands the importance that timely processing of patent applications has on our clients’ business operations and IP strategies. Accordingly, we are committed to minimizing any adverse effects that these changes may have on our clients. We will continue to closely monitor the situation and adapt our strategies to ensure that your patent applications are processed with as little delay as possible.

More Executive Orders Aimed at Improving the Operation of the Federal Government

Executive Order Directing Deregulation and Termination of Certain Regulatory Enforcement Actions

On February 19, 2025, in an executive order titled Ensuring Lawful Governance and Implementing the President’s “Department of Government Efficiency” Deregulatory Initiative, President Trump expressed a policy to “deconstruct[] … the overbearing and burdensome administrative state.” Specifically, President Trump directed each agency head (subject to limited exemptions) to classify all regulations subject to the agency’s sole or shared jurisdiction into one of seven categories. These categories include, for example, “unconstitutional regulations and regulations that raise serious constitutional difficulties,” “regulations that implicate matters of social, political, or economic significance that are not authorized by clear statutory authority,” “regulations that impose significant costs upon private parties that are not outweighed by public benefits,” “regulations that harm the national interest,” and “regulations that impose undue burdens on small business and impede private enterprise and entrepreneurship.” There is no category for a regulation that the agency head finds lawful and appropriate. Each agency head is to provide the Administrator of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) the list of those “unconstitutional regulations and regulations that raise serious constitutional difficulties.” The Administrator of OIRA, then, is tasked with developing an agenda to “rescind or modify these regulations.”

In addition, the executive order directs each agency head to assess whether ongoing enforcement of any regulation identified in the above classification process complies with law and the policies of the Trump administration. On a case-by-case basis and consistent with applicable law, the agency head is to “terminat[e] … all such enforcement proceedings that do not comply” with the executive order’s directive.

Executive Order Affecting Independent Agency Power

On February 18, 2025, in an executive order titled Ensuring Accountability for All Agencies, President Trump amended Executive Order (EO) 12866 to require administrative rulemaking by independent regulatory agencies (such as the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Federal Trade Commission, the National Labor Relations Board, and the banking regulatory agencies (Federal Reserve Board, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency)), which are previously exempted by EO 12866, to go through the regulatory review process promulgated by EO 12866, including submission of any proposed or final rules to the White House’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB) for review before publication.

The executive order further:

Directs the OMB Director to:

Adopt performance standards and management objectives for heads of independent agencies;

Conduct performance reviews over independent agency heads and report to the President; and

Review financial obligations and consult agency heads to adjust budget allocations.

Requires heads of independent agencies to

Consult the OMB and other White House offices on policies and priorities;

Establish a White House liaison position in each agency; and

Submit agency strategic plans to OMB for preclearance before publication.

Prohibits government agencies to advance interpretation of laws in rulemaking or litigations inconsistent with the positions taken by the Attorney General.

Executive Order Reducing the Size and Composition of the Federal Government

On February 19, 2025, in an executive order titled Commencing the Reduction of the Federal Bureaucracy, President Trump directed several actions to reduce the size of the federal government. First, the executive order eliminates, to the maximum extent of the law, the non-statutory components and functions of (i) the Presidio Trust, (ii) the Inter-American Foundation, (iii) the United States African Development Foundation, and (iv) the United States Institute of Peace. The head of each of these entities must submit a report to the OMB Director that (i) states the extent to which it and its components and functions are statutorily mandated and (ii) affirms compliance with the executive order. The OMB Director will terminate or reject funding requests for components or functions that are not statutorily mandated. Second, the Director of the Office of Personnel Management will take steps to eliminate the four Federal Executive Boards and the Presidential Management Fellows Program. Third, the heads of the departments and agencies identified below have been instructed to terminate the following committees and councils:

The Advisory Committee on Voluntary Foreign Aid (U.S. Agency for International Development),

The Academic Research Council and the Credit Union Advisory Council (Consumer Financial Protection Bureau),

The Community Bank Advisory Council (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation),

The Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Long COVID (Department of Health and Human Services), and

The Health Equity Advisory Committee (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services).

Fourth, within 30 days, the Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs, the Assistant to the President for Economic Policy, and the Assistant to the President for Domestic Policy are to recommend additional entities and Federal Advisory Committees to be terminated.

Presidential Memorandum on Disclosure of Terminated Programs, Contracts, and Grants

On February 18, 2025, in a memorandum titled Radical Transparency about Wasteful Spending, President Trump directed the heads of executive departments and agencies to take all appropriate actions to the maximum extent permitted by law to make public the “complete details of terminated programs, cancelled contracts, terminated grants, and any other discontinued obligation of Federal funds.”