California’s SB 53 and Emerging AI Regulation- Strategic Guidance for Founders and Investors

California recently passed the Transparent in Frontier Artificial Intelligence Act (SB 53), which is the first comprehensive state-level AI safety framework in the United States. This law applies mostly to the large AI developers training models with extreme compute (10^26 FLOP) or earning $500m+ annually.

If you are a founder of a tech startup, it is not likely that this law applies directly to you. However, SB53 may still materially impact your startup business. SB 53 introduces regulatory, commercial, and reputational dynamics that are likely to extend well beyond the Golden State.

Below is a summary of what founders of early-stage AI companies and their investors should be preparing for.

AI governance in commercial agreements, financing and exit transactions:

Core elements of SB 53-aligned governance will likely be included in future procurement checklists, representations and warranties and diligence processes. Even in the absence of a legal mandate, failure to implement basic AI governance protocols may disadvantage startups in commercial agreements, financing and exit conversations.

Establishment of industry norms:

Practices such as red-teaming, security controls for model weights, and whistleblower protections are likely to become baseline expectations across the sector. This is not limited to entities that meet SB 53’s technical thresholds.

Acceleration of compliance timelines:

Founders should anticipate requests from investors and partners for documented compliance readiness earlier than historically expected. Early-stage companies may benefit from proactively integrating governance infrastructure into their product and organizational roadmaps. Treating AI governance not merely as a compliance matter, but as a component of strategic positioning may benefit institutional capital raises.

Impact on incumbent strategies:

SB 53 is explicitly designed to limit the ability of large AI labs to avoid safety obligations in the pursuit of speed or scale. Plus, startups should consider engaging with CalCompute, California’s new state-backed computing initiative, which is designed to provide access to infrastructure, guidance, and public-private research resources. These parts of SB 53 could reduce asymmetries that currently favor dominant players.

Strategic positioning for startups:

Voluntary alignment with SB 53 practices can signal institutional readiness and mitigate reputational risk. California’s AI regulatory leadership is likely to influence policy beyond state borders. Much like the GDPR’s impact on global privacy standards, SB 53 may serve as a prototype for future federal or multi-state regulatory frameworks. Key definitions and enforcement thresholds are expected to evolve through 2027.

Comparison to the EU Artificial Intelligence Act:

The EU Artificial Intelligence Act (January 2024) is broader and more of a burden for startups. Obligations focus on providers of high-risk AI systems and general-purpose AI models, with systematic risk. The EU Act’s stricter compliance requirements apply to those trained on 10^25 flops (vs CA’s 10^26). The EU act also requires regulatory submissions, while CA only requires the Frontier Developers and Large Frontier Developers to publish transparency reports. An earlier version of the CA law, closer in similarity to the EU act, was vetoed by Governor Newsome for being too broad and potentially stifling innovation.

While SB 53 may not affect you directly, we believe startups that embed governance and transparency into their operations will differentiate themselves in highly competitive markets and allow them to align with evolving standards, which has the ultimate benefit of de-risking future partnerships and potential financing and acquisition.

New York Poised to Be at the Forefront of AI Regulation; Five Bills Await Gov. Hochul’s Action

Among the hundreds of bills passed during New York’s 2025 legislative session are several pieces of legislation that impose regulations on developing and using AI. While some of the measures are aimed at refining recently adopted laws, some of the bills would regulate the technology in entirely new ways.

The governor is a strong supporter of advancing AI technology, previously stating, “[w]hoever leads in the AI revolution will lead the next generation of innovation and progress, and we’re making sure New York State is on the front lines. With these bold initiatives, we are making sure our state leads the nation in both innovation and accountability. New York is not just keeping pace with the AI revolution – we are setting the standard for how it should be done.”

The governor has until January to approve or veto the various proposals and is currently receiving input from stakeholders before taking action. Below are some of the key AI-related bills under her consideration.

The Responsible AI Safety and Education Act (RAISE Act) (S.6953-B/A.6453-B)

The RAISE Act would require developers of AI models to implement certain safety measures to protect against misuse of their applications. The proposal also includes the potential for significant penalties (up to) $10 million for a first violation and $30 million for repeat violations. While New York’s legislation closely mirrors California’s SB 53, recently signed into law, the RAISE Act is different in scope, applying to businesses that have in excess of $100 million in training costs – not revenue. The RAISE Act would also go farther, requiring companies to submit safety and security policies to describe how they would reduce the risk of critical harm, and explicitly prohibits the deployment of certain models.

Warning Labels for Certain Social Media Platforms (S.4505/ A.5346)

This bill would require social media platforms that use certain design features, including addictive feeds or infinite scrolls, to display warning labels at each point of access. The New York State Office of Mental Health would determine the content of the warning labels. Operators that fail to comply with posting the warnings consistent with requirements would face fines of up to $5,000 per violation. If signed, New York would join other states including Minnesota and California, who recently enacted similar legislation. This bill comes on the heels of New York enacting two other laws aimed at protecting children who use social media, the New York Child Data Protection Act and the SAFE for Kids, for which the attorney general recently released draft regulations.

Synthetic Performers (S.8420-A/ A.8887-B)

This precedent-setting proposal would require commercial advertisements to disclose the use of synthetic performers – digitally created media that appear as real people. The legislation would mandate the creator or producer of the advertisements to disclose such use or face penalties of up to $5,000. The bill contains certain exceptions for advertisements, such as those that are solely audio. While this legislation is the first in the nation to regulate AI in advertising, New York recently enacted a similar law related to the use of deceptive practices, or “deep fakes,” in elections.

Expansion of Right of Publicity Statute (S.8391/ A.8882)

In 2020, New York enacted a right of publicity, requiring consent for the use of the name, image or likeness of a deceased person for commercial purposes. The law also applied to expressive audiovisual works but only required a disclaimer, rather than consent, prior to such use. This legislation expands current law to require prior consent of a deceased person’s heirs for the use of their voice or likeness in media.

Expansion of Legislative Oversight of Automated Decision-making in Government (LOADinG) Act (S.7599-C/ A.8295-D)

In 2024, New York became the first state in the nation to enact a law that effectively limits how state agencies can use AI in decision making processes. Known as the Legislative Oversight of Automated Decision-making in Government (LOADinG) Act, the law provides requirements related to automated decision-making systems state agencies use for certain decisions. This bill would expand the scope of governmental entities that the law applies to and the types of disclosures required, including by state agencies, local governments, and certain educational institutions. Importantly, the legislation would also require the NYS Office of Technology Services to create and maintain a publicly accessible inventory of the types of automated decision-making tools state entities utilize.

Entities potentially subject to these legislative proposals may wish to evaluate the possible impact to operations, policies, and procedures while the governor considers such proposals.

AI FAILURES IN TCPA: First TCPA Decision Addressing a Party’s Use of GenAI in Briefing is Out–And It Sets the Table Well

So in Zelma v. Wonder Group, Inc. 2025 WL 2976546 (D. N.J. Oct. 22, 2025) the Plaintiff appears to have used AI to generate a brief opposing Plaintiff’s motion to dismiss. (Seems like a category 2 situation since Plaintiff isn’t a lawyer.)

Here is what the Court said on the subject (this is long but good):

Plaintiff included fabricated quotations from real cases, and at other points, cited to cases that, to the best of the Court’s knowledge, do not exist. See id.

Accordingly, Plaintiff was ordered to disclose whether he used any generative artificial intelligence while drafting his Opposition and explain the identified discrepancies. Id. In his response, Plaintiff stated that he saw a “wave of Al-based services” when conducting legal research for this matter, and even tested one of the platforms for “off topic input.” D.E. 19-2 (“Plaintiff’s Letter”) at 1. However, this experience “reinforced [his] decision to rely on [his] personal TCPA archive and trust legal databases.” Id

Plaintiff explained the fabricated quotations in his Opposition by stating that he “inadvertently used quotation marks in places where [he] meant only to paraphrase a holding or summarize the spirit of a ruling,” which he now “understand[s] … could misrepresent intent and mislead the Court.” Id. at 2. According to Plaintiff, he had “always used quotes where a supporting statement is made,” but he “now understand[s] the difference between citation and paraphrasing.” Id. And while Plaintiff acknowledged that “some of the cases [he] originally cited can’t be found or verified in official records,” he chalked that up to either “misread[ing] the source or summariz[ing] it poorly.” Id.

Plaintiff’s explanation strains credulity. Plaintiff has, in this district alone, brought nearly two dozen cases. Thus, despite his pro se status, he is not an inexperienced litigant. Plaintiff’s submissions in this case alone demonstrate a familiarity with caselaw and pleading requirements. He even has a database of TCPA cases. If Plaintiff has enough repeat litigation to maintain a compendium of relevant cases, and has even learned how to properly Bluebook his citations, surely he knows how to use quotation marks…

Plaintiff’s above explanation does not fully account for the fabricated quotations and citations within his brief. It also calls into serious doubt the certification attached to his Opposition, in which Plaintiff declared under the penalty of perjury that he reviewed all relevant law, rules and regulations relevant to this matter. D.E. 9-1. The Court will defer its decision on whether to impose any sanctions against Plaintiff until the conclusion of this litigation.

So… yeah.

AI makes up cases. Makes up quotes.

And lawyers think they should use this?

The Ethics Cauldron: Brewing Responsible AI Without Getting Burned

As AI becomes integral to business operations, businesses face unprecedented ethical and legal challenges that extend far beyond technical implementation.

The intersection of AI capabilities with business ethics creates complex dilemmas requiring thoughtful navigation. Beyond traditional concerns about data privacy and security, AI raises fundamental questions about fairness, transparency, accountability, and human dignity.

Companies that successfully navigate these challenges will build sustainable competitive advantages while avoiding costly legal pitfalls and reputational damage. This post explores the critical intersection of AI, ethics, and business law, providing practical guidance for responsible AI deployment.

The New Business Ethics Landscape

The integration of AI into business processes fundamentally alters traditional ethical considerations. Businesses must grapple with how AI systems make decisions affecting employees, customers, and society at large. Key ethical considerations include ensuring AI systems don’t perpetuate or amplify existing biases, maintaining transparency about when and how AI influences decision-making, respecting human autonomy by providing meaningful choices and oversight opportunities, and considering broader societal impacts of AI deployment, including employment effects and social equity.

Modern businesses cannot afford to treat ethics as an afterthought or compliance checkbox. Ethical AI practices build stakeholder trust, reduce regulatory risk, attract top talent, and create sustainable competitive advantages. Companies should establish clear ethical guidelines for AI use that go beyond legal requirements. Regularly audit AI systems for bias, fairness, and unintended consequences. Provide accessible channels for stakeholders to raise concerns about AI decisions without fear of retaliation. Integrate ethical considerations into every stage of AI development and procurement processes, from initial concept through deployment and monitoring.

Consider establishing an AI ethics board or committee with diverse perspectives, including external advisors who can provide independent viewpoints. This body should have real authority to influence AI decisions, not merely serve as window dressing. Develop clear escalation procedures for ethical dilemmas and ensure leadership understands their responsibility for AI outcomes. Remember that ethical AI isn’t just about avoiding harm, it’s about actively promoting beneficial outcomes for all stakeholders.

Protecting Intellectual Property in the AI Age

Generative AI raises complex IP issues. Currently, works produced purely by GenAI are not copyrightable in the U.S., though a mix of human and machine contributions can be. Some jurisdictions, like China, recognize copyright for AI-generated works, while others (the EU, UK) have yet to take a position. Businesses should ensure that human creativity contributes to public-facing content and recognize that AI cannot be an inventor for patent purposes in most jurisdictions.

The legal landscape on fair use and training data is unsettled. Developers argue that using copyrighted works to train AI models is fair use; copyright owners disagree. Businesses building or using AI models should consider licenses for training data, use factual or public-domain content where possible, and monitor evolving case law. End users can also face liability if AI-generated outputs infringe copyrights; using enterprise AI offerings can provide warranties and indemnification. Avoid prompts that ask AI to replicate specific copyrighted content and prefer general summaries.

Trade Secrets and Avoiding Disclosure

AI-generated content can potentially be protected as trade secrets if confidentiality is properly maintained. However, using AI tools creates new risks for trade secret exposure. Employees might inadvertently input confidential information into public AI platforms, where it could be stored, analyzed, or used for model training. Recent incidents involving engineers exposing source code through public AI tools illustrate these risks vividly.

Use closed, enterprise AI systems rather than public tools for any work involving proprietary information. Ensure these systems provide appropriate data isolation and security guarantees. Prohibit employees from uploading trade secrets, confidential business information, or sensitive personal data to public AI platforms. Implement technical controls where possible to prevent unauthorized data sharing. Remind employees regularly that AI conversations may be stored indefinitely and could be accessed by vendors, other users, or through security breaches.

Develop clear classification schemes for information sensitivity and corresponding AI tool permissions. Highly confidential information should only be processed using on-premises or private cloud AI systems with strong security controls. Moderately sensitive information might be appropriate for enterprise cloud AI tools with appropriate contracts. Public information can be processed using consumer AI tools, though output quality and consistency should still be monitored.

Managing Bias and Ensuring Fairness

AI systems can perpetuate or amplify societal biases present in training data, potentially leading to discriminatory outcomes in hiring, lending, insurance, and other critical decisions. Businesses must proactively address bias throughout the AI lifecycle. Start by examining training data for representational imbalances and historical biases. Implement testing procedures to identify disparate impacts across protected categories. Document efforts to detect and mitigate bias, as this documentation may be crucial for regulatory compliance and legal defense.

Establish clear fairness metrics appropriate to your use cases and regularly monitor performance against these benchmarks. Recognize that different fairness definitions may conflict—for example, equality of outcomes versus equality of opportunity. Make conscious choices about fairness trade-offs and document reasoning. Ensure diverse teams participate in AI development and review to identify potential bias blind spots. Consider external audits for high-stakes applications affecting individuals’ opportunities or rights.

Privacy and Data Protection Imperatives

AI systems often require vast amounts of data for training and operation, raising significant privacy concerns. Personal data used in AI systems remains subject to privacy laws, with additional requirements emerging specifically for AI contexts. Implement data minimization principles, using only necessary data for specified purposes.

Provide transparent notices about AI use in privacy policies and at points of data collection. Explain not just that AI is used, but how it affects individuals and what rights they have. Enable meaningful opt-out opportunities where feasible, particularly for non-essential AI applications. Implement strong security measures to protect personal data throughout the AI pipeline, from collection through model training to inference and output generation. Prepare for data subject rights requests, including access, correction, deletion, and explanations of AI decisions.

Building Ethical AI Culture

Creating an ethical AI culture requires more than policies and procedures. Leaders must model responsible AI use and prioritize ethical considerations alongside business objectives. Celebrate examples of employees raising ethical concerns or choosing ethical approaches over expedient ones. Make ethics a regular part of AI discussions, not an afterthought or compliance exercise.

By following these guidelines and embracing ethical AI principles, businesses can leverage AI’s transformative potential while maintaining stakeholder trust and avoiding legal pitfalls. The businesses that get this balance right will define the next era of business competition.

In the final post, we’ll examine how to evaluate AI tools and structure vendor contracts to protect your organization’s interests.

Data Center Development and the Rise of SLA Insurance

Data center development is booming—driven by AI and other high-throughput workloads. But beyond the physical buildout, a new product is emerging that might enhance the sector’s value proposition: SLA insurance.

The capital intensity of data center projects attracts institutional investors. One common vehicle is asset-backed securitization, where data center leases and their associated cash flows are pooled into tradeable bonds, offering predictable returns. Another is commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS), which bundle loans that data center properties secure, generating returns from aggregated mortgage repayments. These instruments thrive on stability. Long-term leases with creditworthy tenants, standardized contract terms, and sustained demand for digital infrastructure make data centers attractive assets in secondary markets.

However, investors remain cautious about operational risks—especially those tied to service level agreements (SLAs). Complex arrangements to build and operate data center campuses couldexpose operators to steep service credits, rent abatement, or even termination rights if performance obligations are not met. These contingencies may threaten income flow and, by extension, the value of securitized instruments.

Drawing inspiration from M&A rep and warranty insurance — a way to guarantee the income-producing contracts and other assets that sellers promise — SLA insurance seeks to offer a similar safeguard for data center investors and operators. The policy pays out in the event of an SLA breach to mitigate downtime risk, strengthen contract enforceability, and enhance the credit profile of the underlying assets. The mere availability of SLA coverage may improve financing terms, potentially making it easier to raise capital.

As SLA insurance gains traction, it might become a standard feature in digital infrastructure transactions. By de-risking operational performance, it could support more aggressive growth strategies, broader investor participation, and deeper liquidity in the data center financing ecosystem. As such, SLA insurance may become a cornerstone of how digital infrastructure is financed, protected, and scaled.

Mapping the Boundaries of Algorithmic Authority

Sometimes the most revealing AI regulations aren’t the ones that say “you must” — they’re the ones that say “you must not.”

We often focus on the rules for developing, deploying, and procuring AI. But what may be more telling is where the rules stop entirely. Not the “how-to” of compliance, but the “you must not” of prohibition. These hard lines, where legislators draw boundaries around algorithmic authority, reveal an emerging consensus about where algorithmic decision-making creates unacceptable risks.

The EU’s Forbidden Zone: Where Algorithms Fear to Tread

Article 5 of the EU AI Act (enforceable since February 2025) bans AI practices presenting “unacceptable risk,” regardless of safeguards or oversight. These are not regulatory speed bumps; rather, they are solid walls. These bans generally target manipulative or surveillance-heavy AI:

Article 5(1)(a): Prohibits AI systems deploying subliminal techniques (e.g., app nudges) beyond a person’s consciousness or purposefully manipulative or deceptive techniques to materially distort behavior, appreciably impairing the person’s ability to make an informed decision and causing them to make a decision they would not have otherwise made, resulting in or likely resulting in physical or psychological harm. Translation: No sneaky AI nudging you into decisions you wouldn’t normally make.

Article 5(1)(b): Bans systems exploiting vulnerabilities of specific groups (e.g., age, disability) to distort behavior, causing or likely causing harm.

Article 5(1)(c): Prohibits social scoring by public authorities evaluating/classifying individuals based on behavior or characteristics, leading to detrimental treatment.

Article 5(1)(h): Restricts real-time remote biometric identification in public spaces for law enforcement, with exceptions for serious crimes, missing persons, or imminent threats.

These prohibitions share a common thread: they challenge human autonomy by bypassing deliberation (subliminal tactics, vulnerability exploitation) or enabling comprehensive surveillance (social scoring, biometric ID).

The American Patchwork: When Algorithms Can’t Make the Call

US jurisdictions target algorithmic decision-making in employment with specific restrictions:

New York City Local Law 144 (effective July 2023):

Requires annual bias audits for automated employment decision tools (AEDTs), examining disparate impact by race/ethnicity and sex;

Mandates notice to candidates/employees about AEDT use; and

Requires publicly available audit results and data retention policy disclosure.

Think of it this way: if your company’s AI resume screener consistently filters out qualified candidates from certain ZIP codes (which can be a proxy for bias and discrimination), you’ll need documentation showing you tested for — and addressed — this bias.

Illinois Artificial Intelligence Video Interview Act (effective January 2020):

Requires notifying applicants about AI use in video interviews and its mechanics;

Mandates consent before use; and

Limits video sharing to evaluators and requires destruction within 30 days upon request.

California Civil Rights Council Regulations (effective October 1, 2025):

Clarify that automated decision systems (ADS) violating existing FEHA anti-discrimination protections are unlawful;

Extend recordkeeping requirements for ADS data to four years; and

Note that anti-bias testing is relevant to discrimination defenses (but not mandated).

The pattern: transparency and accountability in AI-assisted hiring, not outright bans, with a focus on preventing opacity and disparate impact.

State-Level Comprehensive Frameworks

Texas House Bill 149 (TRAIGA, effective January 1, 2026):

Prohibits development or deployment of AI with intent to discriminate against protected classes; and

Requires government entities to disclose to consumers when they interact with AI systems.

Colorado SB 24-205 (Colorado AI Act, effective June 30, 2026, delayed from February 2026):

Targets “high-risk” AI systems with impact assessments, risk management policies, and consumer notice requirements; and

Requires developers and deployers to use reasonable care to prevent algorithmic discrimination.

Other 2025 State-Level Developments:

Utah: Amended its Artificial Intelligence Policy Act (effective May 2025) to narrow disclosure requirements, focusing on “high-risk” AI interactions in regulated occupations and establishing safe harbor provisions for compliant systems.

Connecticut: SB 2, which would have mandated impact assessments for high-risk AI systems, passed the Senate but stalled in the House amid gubernatorial veto threats over innovation concerns.

Virginia: HB 2094, which would have established comprehensive high-risk AI consumer protections, was vetoed by the Governor in March 2025 over concerns about stifling innovation. This development highlights ongoing legislative friction despite broad support for AI regulation.

Credit and Financial Services

Preexisting laws apply to AI-driven credit decisions:

Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA, 15 U.S.C. § 1681 et seq.): Section 615 mandates adverse action notices when decisions are based on consumer reports. Combined with ECOA’s specific reasons requirement, CFPB guidance (Circular 2023-03) emphasizes that complex algorithms must produce explainable adverse action reasons.

Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA, 15 U.S.C. § 1691 et seq.) and Regulation B (12 CFR Part 1002): Section 1002.9(b)(2) requires creditors to provide specific, actionable reasons for adverse decisions. CFPB Circulars 2022-03 and 2023-03 confirm “the algorithm” is not a valid reason.

The Housing Context

The Fair Housing Act (42 U.S.C. § 3601 et seq.) supports disparate impact liability on AI in tenant screening, mortgage underwriting, and property valuations per the 2015 Inclusive Communities Supreme Court decision. However, HUD’s September 2025 withdrawal of disparate impact guidance — including the 2016 post-Inclusive Communities guidance and 2024 AI advertising guidance — signals a dramatic enforcement shift toward intentional discrimination claims only. While HUD has withdrawn its guidance and shifted enforcement priorities, the Fair Housing Act and Inclusive Communities precedent still stands — it’s the enforcement approach, not the law, that has changed.

Healthcare and Insurance

While housing regulators grapple with enforcement priorities, the healthcare sector is charting a clearer path forward.

Colorado SB 21-169: Requires certain insurers to establish governance frameworks and test external consumer data and AI systems for unfair discrimination based on protected classes.

HIPAA Privacy Rule (45 CFR § 164.524): Guarantees individuals access to their protected health information, which may indirectly support review of data used in AI-driven healthcare decisions.

Texas SB 1188 (effective September 2025): Requires healthcare practitioners to maintain human oversight of AI-generated medical decisions, disclose AI use to patients, and physically store electronic health records in the US.

What the Boundaries Reveal

These regulatory frameworks do not ban AI capability, but do generally establish boundaries requiring:

Transparency: Disclosing use and explaining outcomes.

Human Oversight: Preserving decision-making authority, not just involvement.

Contestability: Enabling challenges/appeals of algorithmic decisions.

Accountability: Mandating bias audits, impact assessments, and risk management.

Practical Governance Implications

For AI governance frameworks:

Risk Classification: Map AI use cases against prohibited practices (e.g., social scoring) and high-risk categories (employment, credit).

Human Oversight Architecture: Ensure humans have expertise and authority to evaluate/override AI (in accordance with Texas’s “preserve authority” standard).

Documentation: Conduct required assessments (e.g., NYC bias audits, Colorado discrimination assessments).

Explainability: Meet FCRA/ECOA standards with specific, defensible reasons — not “the algorithm decided.”

Notice and Consent: Comply with specific notice obligations (e.g., Illinois video interviews, Colorado consumer notices).

The Compliance Question

Evaluate AI implementations by asking:

Does this system make consequential decisions (employment, credit, housing, healthcare, benefits)? What specific requirements apply?

Can a human evaluate and override AI reasoning?

Could we defend an adverse decision to a regulator with specific reasons?

Have we conducted required bias audits/impact assessments?

Looking Forward

As of October 2025, states like New York (AI companion safeguards) and California (finalized AI discrimination regs) add layers, while federal efforts (e.g., the AI Bill of Rights) lag. Successful organizations will be those that hardwire human agency and accountability into AI architecture, ensuring compliance with evolving laws. The boundaries are being drawn now — and crossing them, even inadvertently, could prove costly.

California Expands Whistleblower Retaliation Protections for Employees in the AI Sector

On Sept. 29, 2025, California Gov. Newsom signed Senate Bill 53, the Transparency in Frontier Artificial Intelligence Act, into law. Aimed at preventing catastrophic risks from advanced AI systems, the law sets requirements for large developers working with “frontier models”—including mandatory safety measures, adherence to national and international standards, and public transparency reports. A “frontier model” is defined by the amount of computing power used during training, fine-tuning, or modification—specifically, any model requiring more than 10^26 integer or floating-point operations.

Violations may lead to civil penalties, especially for failures that might result in mass harm (injury or death of 50 or more people) or financial losses exceeding one billion dollars. The law takes effect Jan. 1, 2026.

Among its provisions, Senate Bill 53 establishes whistleblower protections in the AI sector. Employees involved in risk assessment, safety management, or incident response are expressly shielded from retaliation when reporting violations or disclosing information about critical safety threats. To safeguard those who speak out, legislators of the bill have implemented notice and internal reporting procedures to ensure employees are able to report or disclose information without fear of retaliation.

What Is Considered a Catastrophic Risk?

“Catastrophic risk” is defined as “a foreseeable and material risk that a developer’s development, storage, use or deployment of a frontier model will materially contribute to the death of, or serious injury to, more than 50 people or more than one billion dollars ($1,000,000) in damage to, or loss of, property arising from a single incident involving a frontier model” doing any of the following:

Providing expert level assistance in the creation or release of a chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear weapon;

Engaging in conduct with no meaningful human oversight that is either a cyberattack or, if the conduct had been committed by a human, would constitute the crime of murder, assault, extortion, or theft; and

Evading the control of its developer or user.

The statute expressly excludes lawful activity of the federal government, harm caused by a frontier model in combination with other software if the frontier model did not materially contribute to the harm, and information that a frontier model outputs if the information is otherwise publicly accessible in a substantially similar form from another source.

Which Employers Are Covered?

The new law applies to large developers of AI systems that have trained or are training a “frontier model.” It imposes additional requirements on those whose annual gross revenues exceeded $500 million in the preceding calendar year. While some current models do not reach this high technical threshold, ongoing technological advancements may bring many models above this level in the coming years.

Who Qualifies as an Employee?

Covered employees include any employee responsible for assessing, managing, or addressing risk of critical safety incidents.

Critical safety incidents include the following:

Unauthorized access to, modification of, or theft of the model weights of a foundation model that results in death, bodily injury, or damage to property;

Harm resulting from a catastrophic risk, which includes events that lead to the death or serious injury of more than 50 people or more than one billion dollars in financial harm;

Loss of control of a foundation model causing death or bodily injury; and

A foundation model employing deceptive techniques against the frontier developer to subvert the developer’s controls or monitoring—outside of a context of an evaluation designed to elicit this behavior—in a manner that increases catastrophic risk.

Overview of New Whistleblower Protections Statute

Prohibited Conduct

Employers and large developers are prohibited from adopting or enforcing any rule, regulation, policy, or contract that prevents employees from disclosing information about activities posing a catastrophic risk or violations of the law. Employees are protected if they have reasonable cause to believe the information they disclose reveals such risks or violations, and they may report to the attorney general, federal authorities, persons of authority over employees at their company, or authorized investigators. Cal. Labor Code § 1107.1(a).

Notice and Acknowledgement Requirements

Employers must provide clear notice to all employees about their rights under the law. This includes posting notices in the workplace, notifying new hires, and ensuring remote employees receive equivalent information. Written notice must be provided annually, with employees required to acknowledge receipt. Cal. Labor Code § 1107.1(d).

Internal Reporting Process Requirements

The law requires employers to implement a reasonable internal process for covered employees to anonymously report concerns about catastrophic risks or violations of the new law. Employers must provide monthly updates to the reporting employee on the status of investigations and responsive actions. Summaries of disclosures and responses must be shared with company officers and directors quarterly, except when those individuals are implicated in the alleged wrongdoing. Cal. Labor Code § 1107.1(e).

Consequences for Non-Compliance

Failing to comply may be costly. In addition to the attorney general having sole authority to seek civil penalties up to one million dollars per violation through a civil action, covered employees may also sue if they experience retaliatory adverse employment actions. Covered employees may pursue damages for any harm suffered, injunctive relief, and recovery of attorneys’ fees.

Takeaways for Employers

Employers—particularly those developing AI or collaborating with major AI developers—should consider proactively updating internal policies and employee contracts to support safe, protected reporting of critical safety incidents, whether within the organization or to external authorities. Considering California’s expansive definitions of “employee” and joint employer liability, AI developers may wish to also ensure that their service providers and contractors adopt compliant practices. This may require a review of not only internal contracts with direct hires but also third-party contracts for consistency with the law’s requirements.

Finally, employers may wish to carefully review all adverse actions taken against covered employees to confirm they are not retaliatory. Internal processes may need to be strengthened to safeguard employees who report safety concerns or potential violations.

New Federal Legislation Proposes Product Liability Standards for AI Systems

Highlights

Broad Definition of Covered AI Products. The AI LEAD Act would define “Artificial Intelligence Systems” as software, tools, or applications that use algorithms or machine learning to make or assist in decisions—whether standalone or built into larger systems.

Potential Developer and Deployer Liability. Developers could face claims for defective design, failure to warn, breach of express warranty, and strict liability. Deployers may be liable for unauthorized modifications or misuse but can seek dismissal if the developer is available and solvent.

A Federal Cause of Action. The bill creates a federal right of action for individuals, state attorneys general, and the U.S. Attorney General, with a four-year statute of limitations and additional protections for minors.

Retroactive Reach. The legislation would apply to suits filed after enactment, even if the alleged harm occurred beforehand—raising potential due process and fairness concerns.

The Senate recently received S.2937, the AI LEAD Act (Aligning Incentives for Leadership, Excellence, and Advancement in Development Act) introduced on Sept. 29, 2025 by Sens. Dick Durbin (Ill.) and Josh Hawley (Mo.). The Act seeks to establish federal product liability standards tailored to artificial intelligence technologies.

What AI-Related Systems Would be Defined as “Products”

The bill covers “Artificial Intelligence Systems,” which it deems “covered products” under the proposed legislation. It also defines these “covered products” broadly as any software, data system, application, tool, or utility that:

Is capable of making or facilitating predictions, recommendations, actions, or decisions for a given set of human- or machine-defined objectives; and

Uses machine learning algorithms, statistical or symbolic models, or other algorithmic or computational methods (whether dynamic or static) that affect or facilitate actions or decision-making in real or virtual environments.

The bill expressly provides that an AI system may be integrated into, or operate in conjunction with, other hardware or software. As drafted, “covered products” under this Act would encompass not only standalone AI applications such as chatbots, but would also include AI components embedded into larger systems.

The legislation takes the fundamental position that these AI systems constitute “products” within traditional liability frameworks, foreclosing potential arguments for platform immunity under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act.

Potential Liability: Developers and Deployers of AI

The bill envisions potential liability for both developers and deployers of AI technology. It identifies various grounds for potential developer liability, arising under four distinct theories:

Defective design, with proof from plaintiffs that a reasonable alternative design was feasible;

Failure to warn;

Breach of express warranty; and

Strict liability

Plaintiffs also could rely on circumstantial evidence to support an inference of product defect when harm ordinarily occurs from such defects. The proposed legislation further prohibits developers from including user agreement terms that would waive rights, limit forums or produces, or unreasonably restrict liability — rendering such clauses unenforceable.

Additionally, deployers of AI technology could be liable when they make ‘substantial modifications,” or deliberate changes that alter the product’s purpose, use function, or design that are not authorized by the developer or otherwise intentionally misuse the technology contrary to its intended use. However, deployers could seek dismissal from such litigation if the developer of the at-issue technology is available, solvent, and subject to the court’s jurisdiction, absent independent deployer liability.

A Federal Cause of Action

The bill specifically creates a federal cause of action enabling the Attorney General, state attorneys general, individuals, or class actions to bring claims in federal district court, with a four-year statute of limitations applicable to such claims. In addition, the proposed legislation seeks to establish heightened safeguards for minor users. In particular, it provides that risk cannot be presumed “open and obvious” to users under the age of 18.

Potential Shortcomings of the AI LEAD Act

Most notably, the Act would apply retroactively to any action commenced after its enactment, regardless of when the underlying alleged harm and related alleged conduct occurred.

While the bill represents a significant legislative attempt to address alleged AI-related harms, it may face conceptual and practical hurdles. Traditional product liability frameworks are not a tight fit for the kinds of AI technologies called out in the bill, with unique challenges possible when it comes to establishing causation and identifying any so-called “defects” at the time of sale due to the “learning” nature of these technologies. Critics argue the bill may stifle innovation, while others contend that the standards outlined in the bill are too vague to provide meaningful guidance.

What to Consider Today

Although this bill is in the early stages, developers and users of AI technology should consider:

Prompt Compliance Review. Consider conducting comprehensive risk assessments of existing products, focusing on design, training data selection, testing protocols, and adequacy of warnings.

Document, Document, Document! Maintain records of design-related decisions, testing, risk assessments, alternative designs considered, and the rationale for choices made. This documentation may be critical in defending against negligence claims.

Remain Aware of the Standards Applicable to Minors. Under this legislation, the “open and obvious” defense is unavailable for users under 18 years of age. Be intentional when considering minor users.

Emerging Technology Frontiers- Redefining Risk, Control, and Value in Transactions

As Silicon Valley develops the next evolution of technologies from artificial intelligence (AI) to next generation computing, private equity (PE) and venture capital (VC) investors are also facing the next evolution in legal and regulatory challenges that did not exist even five years ago. Historically, innovation outpaces the regulations designed to govern it, and that is certainly true today. So, for investors and legal advisors, transactions involving these frontier technologies are not just about identifying opportunity, but rather rethinking the fundamentals of dealmaking and how risk, control, and value are defined.

The Evolution in Evaluating Transactions

In a traditional VC or PE transaction, there is a clear sense of ownership, intellectual property (IP), and governance. However, when dealing with these cutting-edge technologies, the lines are blurred, and traditional assumptions do not necessarily hold.

Risk must be redefined to expand well beyond just financial exposure or regulatory compliance. It should account for algorithmic accountability, data integrity, and technological sustainability. Control also becomes more complex when value flows through distributed networks, open-sourced frameworks, or autonomous systems. And then there is the recalibration of value itself, as it can no longer be defined solely by tangible assets or traditional revenue models.

The Increasing Importance of Strategic Foresight

Dealmakers should take a more fluid approach to diligence and structuring, thinking beyond the restrictions of static agreements and traditional deal models. Legal teams must anticipate how these rapidly evolving technologies will intersect with regulation, competition, and market expectations, which are also continually changing. And investors must examine not only the value of the technologies companies are developing, but also how resilient that technology and the business model will be as policies shift and new disruptive technologies come online in the future. This kind of strategic foresight is critical.

Strategic foresight involves evaluating how emerging technologies will interact with issues such as shifting antitrust enforcement, data privacy laws, and geopolitical concerns. To effectively do this, harder questions must be asked. Does the company’s core technology depend on data that may later be restricted or regulated? Could its algorithms or AI models trigger new forms of liability as standards evolve? Or are there export control or national security concerns tied to the company’s R&D partnerships? These are the kinds of issues that must be considered as they can affect valuation, timing, and risk.

Bridging the Innovation and Regulation Gap

It is critical to bridge the gap between innovation and regulation. Legal advisors play a key role here, helping founders and investors align cutting-edge technology with practical, enforceable business terms. Legal teams can help shape how risk is allocated and mitigated by crafting and negotiating agreements that are flexible enough to accommodate technological change and consider alternative structures such as staged acquisitions, earn-outs, or joint ventures that let buyers and investors calibrate exposure as a company’s technology matures or as regulatory clarity improves.

When strategic foresight is coupled with a deep understanding of the rapidly changing technology landscape, attorneys can help clients build deal structures that are capable of withstanding policy shifts, public scrutiny, and the relentless pace of innovation that defines Silicon Valley. The best legal advice isn’t just about closing the deal, it’s about positioning the company, and its investors, to be prepared and to thrive no matter what comes next

National Security Meets Investment: Understanding the United Kingdom’s Evolving NSI Regime

The UK National Security and Investment Act 2021 (NSI Act) created a stand‑alone UK screening regime for acquisitions of control over entities and assets that may pose a national security risk. It applies irrespective of deal value or the acquirer’s nationality.

We have previously written about the NSI Act’s operative provisions and about foreign direct investment (FDI) regimes, as well as keeping abreast of updates (see here and here).

The NSI Act has now become a standard consideration for deal lawyers advising on UK transactions. The UK government is prepared to intervene significantly in transactions if it considers that they pose a risk to national security, and this trend looks likely to continue. In addition, because the NSI Act applies to transactions involving technology and artificial intelligence (AI), given the key importance of both those sectors to the UK economy, it will continue to be a relevant, significant consideration for deals for the foreseeable future. Therefore, in this article, we summarise the key aspects of the NSI Act, including the mandatory notification regime, the UK government’s call-in powers and some practical points for parties to consider.

What does the NSI Act cover?

The NSI Act applies to transactions involving the acquisition of a specified level of control over “qualifying entities” or “qualifying assets.” Qualifying entities include any entity other than an individual; qualifying assets include land, tangible moveable property and intangible assets like ideas, information or techniques with economic value that are used in connection with activities or supplies in the United Kingdom (collectively, Qualifying Targets). Its ambit can extend to entities and assets located outside the United Kingdom, provided there is a sufficient UK nexus. Notably, the NSI Act does not impose any thresholds based on turnover, market share or deal value, and UK investors are not exempt.

Core features of the NSI Act

Decision maker and scope. The NSI Act applies across the United Kingdom, with most provisions in force from 4 January 2022, and a call‑in power that captures qualifying acquisitions completed on or after 12 November 2020. While the NSI Act does not define “national security,” the factors guiding call‑in are set out in the statutory Section 3 statement (updated May 2024). The regime is administered by the Investment Security Unit (ISU) in the Cabinet Office, with decisions taken by the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster (the Secretary of State in the Cabinet Office).

Trigger events (control thresholds). The NSI Act captures a range of transactions (Trigger Events) that involve acquiring control over qualifying entities or assets. These include:

shareholdings and voting rights crossing specified thresholds;

rights enabling or preventing the passage of resolutions;

acquisitions of “material influence” over a qualifying entity’s policy; and

rights in qualifying assets enabling use of, or control over, the asset.

Mandatory notification. Acquisitions of control over qualifying entities that carry on activities in any of the specified sensitive sectors must be notified and cleared pre‑completion. The sectors in scope include: advanced materials; advanced robotics; artificial intelligence; civil nuclear; communications; computing hardware; critical suppliers to government; critical suppliers to the emergency services; cryptographic authentication; data infrastructure; defence; energy; military and dual‑use; quantum technologies; satellite and space; synthetic biology; and transport. A mandatorily notifiable acquisition completed without approval will be void. In addition, significant sanctions may apply, including fines of up to the greater of £10 million or 5 percent of global turnover, and potential imprisonment for individuals involved.

Voluntary notification. If a transaction is not subject to mandatory notification but nonetheless may present national security concerns, submitting a voluntary notice can offer greater transactional certainty and protect the parties from the risk of a later call-in. Unlike mandatory cases, voluntary notices can be filed pre‑ or post‑completion.

Call-in power. For acquisitions that are not notified, the Secretary of State has the power to call in the transaction for review within six months of becoming aware of it, and up to five years after completion. However, this five-year limit does not apply in cases where a mandatory notification was required but not made. The Secretary of State may “call in” any in‑scope acquisition (notified or not) for national security assessment if there is a reasonable suspicion of a national security risk. The call-in power applies to deals completed since 12 November 2020. In the year 1 April 2024 to 31 March 2025, under the NSI Act, 56 deals were called-in for full review, of which 49 were for notified acquisitions – an increase on the previous year.

Remedies and sanctions. The Secretary of State may impose conditions, prohibit or unwind transactions, and levy civil/criminal penalties for noncompliance.

Notifying in‑scope transactions

Notification process and initial screening

The ISU can discuss scope and process on a non‑binding basis and can provide guidance on whether a particular acquisition is notifiable in cases of genuine uncertainty.

Notices are submitted via the NSI electronic portal and must be in the prescribed form. A representative, such as a law firm, may submit on behalf of the notifying party.

Once a notice is submitted, acceptance by the ISU typically takes about a week – recently, the median has been seven working days for mandatory notifications and eight for voluntary notifications. After acceptance, the Secretary of State has 30 working days to either clear the transaction or call it in for further review. Importantly, the issuance of information or attendance notices during the screening period does not pause the 30-day review timeline.

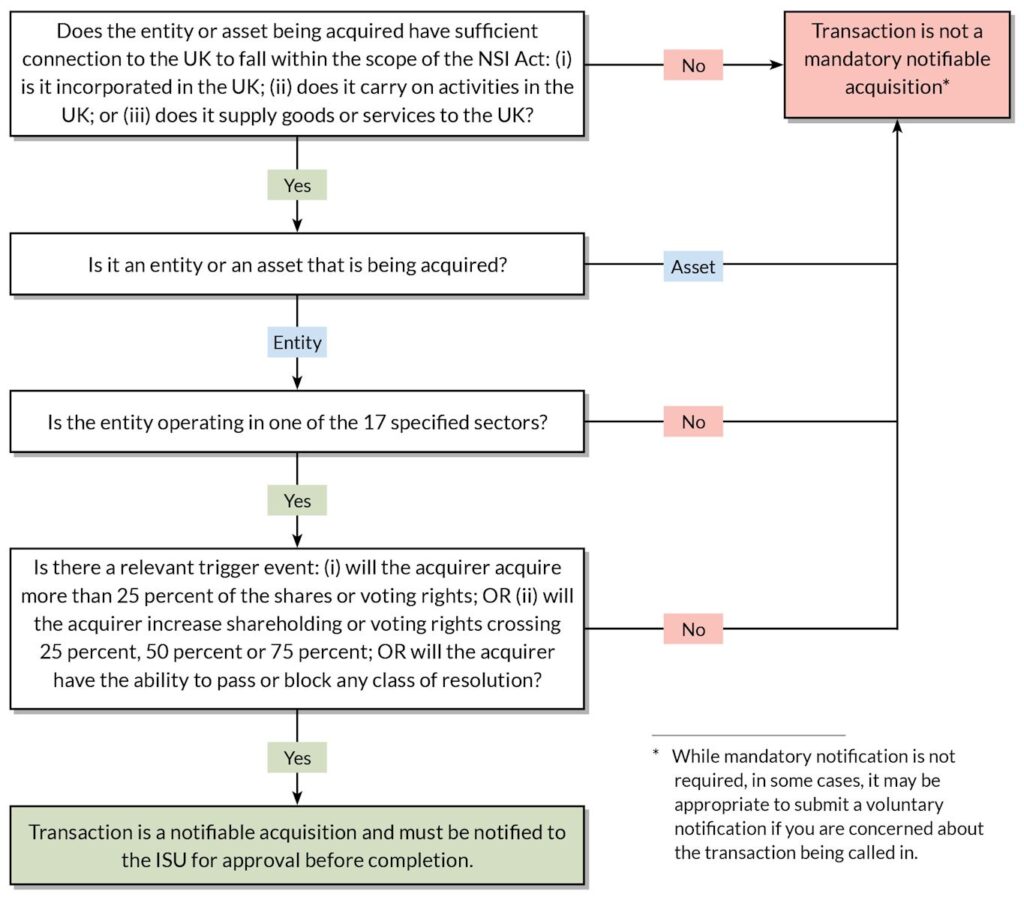

A flowchart to assess whether a transaction is notifiable appears at the end of this article.

Retrospective validation of void notifiable acquisitions

If a mandatory filing was missed and the deal completed, the Secretary of State must either call in the acquisition or issue a validation notice within six months of becoming aware. Affected parties can also apply for a validation notice. If granted, the acquisition is treated as approved and ceases to be void.

Call‑in power and how risk is assessed

Call‑in notices and time limits

The Secretary of State has the authority to call in a qualifying acquisition that is in progress, under contemplation or completed, provided this occurs within the relevant statutory time limits.

For acquisitions completed before the main commencement of the regime, specifically between 12 November 2020 and 3 January 2022, the Secretary of State may still exercise the call-in power, subject to specific timing rules and exceptions where intervention under the Enterprise Act has already taken place.

For transactions that have been notified, the decision to call in must be made within 30 working days of the notice being accepted. For non-notified transactions, the general rule is that the Secretary of State may call in the deal within six months of becoming aware of it, and up to five years after completion.

Section 3 statement: risk factors

The following are considered risk factors under the Section 3 statement:

Target risk. What the entity or asset does, is used for or could be used for; proximity to sensitive sites; and critical supply relationships. Deals within or closely linked to the mandatory sectors are more likely to be called in.

Control risk. The type and degree of control acquired (including cumulative and financing‑related control), and whether that could be used to harm national security.

Acquirer risk. Characteristics such as past behaviour, sectoral capabilities, cumulative holdings, ties or obligations to hostile states or organisations, and sanctions exposure. UK origin does not confer immunity; state‑owned/sovereign investors are not inherently riskier, but ties to hostile actors are relevant.

Assets and land. Asset call‑ins are more likely when connected to mandatory‑sector activities or where land is, or is proximate to, sensitive sites. Export controls and ECJU licensing are considered.

Extraterritorial scope. Non‑UK entities/assets may be called in where there is a UK nexus, including outward direct investments transferring sensitive technology/intellectual property (IP) to non‑UK entities.

National security assessment following call‑in

Timelines and procedure

Once a transaction is called in, the Secretary of State has an initial assessment period of 30 working days, which can be extended by an additional 45 working days if the Secretary of State determines that such extension is needed. If a national security risk is identified and additional time is required to develop appropriate remedies, the parties may agree to a further voluntary extension.

During the assessment period, the timeline may be paused if the Secretary of State issues information or attendance notices. The assessment clock will only resume once the requested information is provided or the notice expires.

Interim orders and information powers

The Secretary of State has the power to issue interim orders during the assessment process. These orders can prevent a transaction from being completed. For example, the Secretary of State could order the parties to refrain from sharing IP or other information. In the case of a transaction that has already completed, the Secretary of State could order the parties to cease taking any steps towards integrating the relevant businesses. Breaching an interim order constitutes both a civil and criminal offence.

Additionally, the Secretary of State may issue information notices, requiring parties to provide documents or attend interviews. These notices can be served extra-territorially on individuals and businesses with a UK connection. Supplying false or misleading information in response to such notices is a criminal offence.

Outcomes and remedies

Clearance. Final notification confirms no further action.

Final orders. Imposed where a national security risk is found and conditions are necessary and proportionate. Conditions commonly address access to sensitive sites/information, governance, supply continuity, UK location of key functions, or restrictions on technology transfer. Prohibitions or unwind orders are possible in rare cases.

Variation/revocation. Final orders are kept under review and can be varied or revoked. Parties may request changes.

Financial assistance. In exceptional cases and with HM Treasury approval, financial assistance may be granted to implement a final order. However, it is worth noting that none has been granted to date.

Sanctions, enforcement and appeals

Civil penalties. For completing notifiable acquisitions without approval, breaching orders or failing to comply with information/attendance notices. Maximum fixed penalties:

Businesses: higher of £10 million or 5 percent worldwide turnover.

Individuals: up to £10 million.

Daily penalties may apply for continuing breaches of orders or information/attendance notices (up to the higher of 0.1 percent worldwide turnover or £200,000 for businesses; up to £200,000 for individuals).

Criminal penalties. For serious offences, including completing a notifiable acquisition without approval, breaching orders and certain information‑related offences. Sentences include up to five years of imprisonment.

Extra‑territorial application. Offences may be committed by conduct inside or outside the United Kingdom. Interim/final orders can apply to conduct outside the United Kingdom where the person has specified UK links.

Civil enforcement. Orders and notices can be enforced by injunction or other relief.

Appeals and judicial review. Monetary penalties are subject to a full merits appeal in the High Court (or equivalent) within 28 days. Other decisions are subject to judicial review, typically within 28 days of grounds arising. No decision has been successfully appealed to date.

The bigger picture: regulation, guidance, reform and next steps

Interaction with merger control and other regimes

CMA merger control. NSI screening runs in parallel with CMA processes. The Secretary of State can direct the CMA to act (or not act) where necessary to avoid undermining national security remedies. The CMA must provide information and assistance to the Secretary of State.

Takeover Code, export control and sectoral rules. Parties must also consider applicable Takeover Code requirements, export controls (ECJU licensing) and any sector‑specific regulations.

Guidance and administration

Comprehensive government guidance is available to help parties navigate the NSI regime. This includes detailed information on how to apply the rules, sector definitions for notifiable acquisitions, instructions for completing notification forms, considerations for academia and research, extra-UK application, market practice, process and timelines, publication policy, and compliance and enforcement. Notably, the Section 3 statement and market guidance were updated in May 2024, and the NSI notification service and templates were refreshed in 2025.

Early and well-evidenced engagement with the ISU is strongly recommended, especially for complex sector assessments, questions regarding non-UK nexus and specific timing requirements. Proactive communication with the ISU can help streamline the process and address potential issues before they arise.

Forthcoming reforms

The UK government is currently consulting (closes 14 October 2025) on updating sector definitions, including:

adding water as a new sector;

creating standalone sectors for semiconductors and critical minerals; and

clarifying and refining several existing sector schedules (for example, AI, data infrastructure, communications, energy, defence and synthetic biology).

The UK government has also announced its intention to exclude certain internal reorganisations and the appointment of liquidators, special administrators and official receivers from the regime.

Practical points for clients

Build NSI into deal planning. Allow time for acceptance plus a 30‑working‑day screening period. Where call‑in is plausible, budget for up to 75 working days of assessment (plus potential clock‑stops) and possible interim orders.

Test for mandatory filing early. Map target activities against the sector schedules. Be alert to adjacent activities and supply chain roles, and to indirect acquisitions through chains of ownership.

Consider voluntary filings. Where target, control or acquirer characteristics could raise risk, a voluntary notice may de‑risk timing and execution.

Intra‑group reorganisations and financing. Internal reorganisations and enforcement over shares can be caught if control thresholds are crossed. While equitable share security at grant typically does not confer control, enforcement or legal title arrangements may. Take counsel and plan filings/conditions accordingly.

Non‑UK targets and assets. Overseas entities that supply into or carry on activities in the United Kingdom, or overseas assets used in connection with UK activities, can be in scope. Outward transfers of sensitive IP/technology may be called in.

UK investors are in scope. Nationality does not determine whether a transaction is notifiable. Acquirer risk is assessed on a case-by-case basis.

Accuracy matters. Provide complete and accurate information. False or misleading information can reopen decisions and constitutes an offence.

Coordinate with other regimes. Align NSI assessments with CMA merger control, Takeover Code, export control and sectoral authorisations.

If you would like tailored guidance on whether your transaction is within scope, whether to notify, and how best to structure and timetable your deal in light of the NSI regime and the ongoing consultation, please contact us.

Should I notify the ISU?

*Eleanor Bines, a trainee in our London office, contributed to this advisory.

State Law Trends, “Captive Audience” Ban Clash, Rhode Island Menopause Law [Video, Podcast]

This week, we’re covering an uptick in state-level employment law activity, federal court decisions on “captive audience” bans, and Rhode Island’s new menopause accommodation requirements.

State Legislative Activity Increases

California has introduced new laws on paid sick leave, artificial intelligence, pay equity, and protections for tipped workers. Meanwhile, other states are also rolling out new laws impacting employment practices.

Courts Clash Over “Captive Audience” Bans

Federal courts have issued conflicting rulings on state restrictions regarding employer-mandated meetings related to union organizing.

Rhode Island Enacts First-Ever Menopause Law

Through a new amendment to its Fair Employment Practices Act, Rhode Island has become the first state in the country to require employers with four or more employees to accommodate menopause symptoms.

The AI Workplace: Legal Considerations for Deploying AI Notetakers [Podcast]

In this episode of The AI Workplace podcast series, Sam Sedaei (associate, Chicago) is joined by Simone Francis (Office Managing Shareholder, St. Thomas; shareholder, New York) to unpack what AI notetakers are and the legal risks they raise at work, including all‑party consent, privacy and notice obligations, privilege and trade secrets, NLRA considerations, transcript access/retention, and litigation holds. The speakers also discuss vendor due diligence, limits on training data, security controls, and how to craft clear, balanced policies tailored to different use cases and audiences.