How Hemp Retailers Can Comply with Alabama’s Consumable Hemp Law by January 1, 2026

The Traveling Wilburys – perhaps the musical supergroup most aligned with the mood and spirit of the Budding Trends blog – tell us that it’s all right to live the life you please. The state of Alabama, however, has determined that the End of the Line for unregulated consumable hemp is January 1, 2026.

As a reminder, Alabama enacted comprehensive reform of consumable hemp products during the last legislative session. While consumable hemp products are not outright banned under Alabama’s new regime, the who, what, when, where, and how of product offerings are all substantially impacted.

We invite you to read on to see what steps Alabama hemp operators should ensure are taken to comply with each of the provisions of the new law.

What Does HB 445 Prohibit?

Starting on January 1, the sale or possession of consumable hemp products in violation of HB 445 (and sale or possession unlawful hemp products generally) can lead to statutory fines and a class C felony, which includes fines up to $15,000 and potential jail time of one to 10 years.

That is, a person in possession of a Delta-8 vape pen arguably faces the same criminal liability as a person in possession of 1 gram of cocaine or 1 gram of methamphetamine. Don’t ask us why — that’s a question better served for the Alabama Legislature.

And this is not a hypothetical risk. As if hemp operators need a reminder, ABC and local law enforcement will likely enforce HB 445 quickly and harshly. Just before the effective date of HB 445 in July, law enforcement conducted broad, state-wide sweeps of hemp operators, which, in some cases, resulted in the confiscation of up to 60 pounds of product. Consumable hemp operators must be aware that similar sweeps are likely inevitable come January 1, 2026.

What Products Are Impacted?

Any hemp product intended for human or animal consumption. A consumable hemp product is defined as a “finished product that is intended for human or animal consumption and that contains any part of the hemp plant or any compound, concentrate, extract, isolate, or resin derived from hemp. The term includes, but is not limited to, products that contain cannabinoids.” The definition has two important carve outs.

First, any smokable hemp product is not considered a “consumable hemp product.” Smokable is defined to include any product that is heated by combustion, battery, or other means to produce a smoke or vapor. Thus, vapes and flower alike are not consumable hemp products (making them unlawful hemp products).

Second, any product that contains psychoactive cannabinoids that are created by chemical synthesis using non-cannabis materials are not considered “consumable hemp products.” Similarly, those products are also defined as unlawful hemp products, and they are subject to prosecution immediately, even before January 1, 2026.

What Happens if I Sell “Unlawful” Hemp Products?

The sale or possession of an unlawful hemp product, which includes the sale of consumable hemp products by an unlicensed person or a sale that violates the packing restrictions, product content requirements, or labeling requirements, is a class C felony.

Who Can Sell Consumable Hemp Products in Alabama After January 1, 2026?

Only retailers licensed by the ABC Board may sell consumable hemp products in Alabama after the New Year.

Can I Sell Consumable Hemp Products at Just Any Retail Location?

No. Permitted retailer locations generally fall into three categories: 1) hemp “dispensaries;” 2) pharmacies; or 3) grocery stores. Each category requires a location-specific consumable hemp product retailer license, which permits certain retail locations to sell only certain forms of consumable hemp products. For example, hemp dispensaries may sell all forms of consumable hemp products (that is, beverages, edibles, and topical or sublingual products), while retail grocers may only sell consumable hemp beverages. Pharmacies are limited to topical or sublingual consumable hemp products. Of great significance to many, consumable hemp products cannot be sold at convenience stores (currently perhaps the largest point of sale for such products).

In addition, grocery stores and dispensaries must meet certain dimensional requirements, which can be found in Sections 28-12-45(c)(2) and 28-12-45(d)(1), respectively.

Have Noteworthy Hemp Beverage Regulation Changes Been Made Since the Last Set of Proposed Rules?

Yes. The initial regulations promulgated by the ABC Board, which would have required two levels of child-proofing containers, have been modified to allow for the standard type of pop-top typically found on a beer can. This is a significant cost saver for manufacturers. Second, whereas the initial regulations would have required hemp beverages to be locked behind glass and require an employee to retrieve the product, ABC will now allow for unlocked plexiglass that does not require assistance from an employee. In short, while the beverages will be in a different refrigerator from beer, they will be available in the same type of self-service manner as beer. Of course, the beverages will only be available to customers age 21+.

How Do I Sell Consumable Hemp Products in Alabama after January 1, 2026?

Consumable hemp products will be subject to similar types of age-gating (21+), testing, packaging, labeling, and advertising, as will medical cannabis products. And as with medical cannabis products, the first step will be to obtain a license (but not without first running your plans by the local government).

Step 1a: Locate Your Business in a Municipality That Approves of the Sale of Consumable Hemp

For the ABC Board to issue a license, the municipal government covering the jurisdiction in which the retail store is located must approve the retailer’s application for licensure. Thus, practically speaking, a retailer’s first step must be to determine whether the municipality will allow consumable hemp products to be sold (or permit the retailer, specifically, to sell consumable hemp products) within its jurisdiction. This requirement may prove difficult because some municipalities, including Auburn, Millbrook, and Pike Road, have signaled they will not permit the sale of consumable hemp products in their jurisdictions.

Step 1b: Obtain a Consumable Hemp Retailer License

After verifying municipal approval, a written application (and accompanying $50 filing fee) must be submitted to the board by “applicants,” which includes every individual (excluding publicly traded companies) that has a 10% or more stake in the business. This requirement includes the members of any partnerships, associations, or LLCs that meet the ownership threshold as well.

The following information must be included in the application:

Approval letter from the municipality in which the store is located;

Name, DOB, place of birth, address, phone number, driver’s license number, and Social Security number of every applicant;

Proof every applicant is lawfully present in the United States;

Authorization to perform a criminal background check;

Two sets of fingerprints taken by a person trained in fingerprinting;

Complete criminal court record of all arrests and subsequent dispositions for each applicant for the past 10 years;

Acquisition and proof of a $25,000 surety bond for each location;

Proof of ownership or lawful possession of the retail location; and

Certification that all information in the application is accurate.

If the board determines the application is sufficient, it must issue the license, whereupon the licensee must pay a $1,000 licensing fee.

Step 2: Ensure the Product Meets Serving Size and Content Restrictions

Serving sizes for both beverages and edibles are limited to 10 milligrams of THC (topical, sublingual, and other products that are not beverages or edibles may contain 40 milligrams). An edible must be individually wrapped, and a carton of edibles may not contain more than 40 milligrams of THC. For example, a carton containing 10 milligram edibles may only contain four individually wrapped edibles. Similarly, consumable hemp beverages may not exceed 12 fluid ounces and, if in a carton, cannot contain more than four beverages.

Step 3: Test the Product & Obtain a Certificate of Analysis

For starters, each product must be tested by an independent lab and receive a certificate of analysis detailing that the product meets certain requirements and is fit for consumption. As a practical matter, we suggest doing this after ensuring the product meets serving size and content restrictions through in-house potency testing.

The certificate of analysis must include many different product analyses. The certificate must include, but is not limited to, the cannabinoid content and potency; terpene profiles; heavy metal concentrations; chemical concentrations; and residual insecticide, fungicide, herbicide concentrations. The certificate of analysis must identify the products tested by batch number and include the date of certificate issuance, the method of analysis for each test conducted, the product name, a scannable barcode linked to the consumable hemp product’s label, the cannabinoid profile by the percentage dry weight of CBD and total THC (which cannot exceed the amount listed on the product label), and a listing of all ingredients in each product. For a full list of Certificate of Analysis requirements, look to Section 28-12-22.

Step 4: Ensure Proper Packaging of the Product

Consistent with the purpose of Alabama’s hemp regulations, all consumable hemp products must not be packaged in a manner that appeals to children. That is, they may not contain cartoon-like characters of people, animals, or fruit. Additionally, consumable hemp products must not be modeled after a brand of products that is primarily marketed to children (e.g., Warheads, Lemon Drop, Airheads, or other candy or children’s food characters). The product cannot reference terms such as candy, cake, cupcake, or pie in its names or slogan. Similarly, the product cannot contain imagery that imitates school supplies, office supplies, and personal items (e.g., cell phones, earbuds, watches, handheld gaming systems). Finally, the product cannot be branded in a fashion that would lead someone to reasonably believe the package contains anything other than a consumable hemp product.

Step 5: Properly Label the Product and Get the Label Approved

As with many consumable products, hemp products must include a list of all ingredients in descending order of predominance and be labeled with the manufacture date, expiration date, serving size, total number of milligrams in the container, and total number of milligrams per serving size. Like the certificate of analysis, each consumable hemp container must include a scannable barcode or quick response code that is linked to the certificate of analysis. Finally, a myriad of warnings must be included on the label, one of which is a warning to keep the product out of the reach of children. For a full list of label warnings, look to Section 28-12-25.

Finally, a retailer or manufacturer may submit its label, along with a $50 label approval fee, to the board for approval.

Step 6: Comply with Operational and Display Requirements

Certain operational and display requirements apply to each type of license holder.

Hemp dispensaries must only sell consumable hemp products or hold a Lounge Retail Liquor (Class II) license, restrict access to the property for those under 21 years of age (including employees), post a sign (8.5” x 11”) at the entrance detailing the age requirement, and may only sell for purposes of off-premises consumption.

For grocery stores, sales must be limited to consumable hemp beverages. The beverages must be in their own refrigerator or shelved separately (and behind some form of glass or clear plastic) from other alcoholic or non-alcoholic beverages. Importantly, a sign (8.5” x 11”) must be posted on the refrigerator or glass/plastic separator that reads: “These products contain hemp derived compounds. Must be 21 years of age or older to purchase.” Finally, the beverages cannot be visible from an area that contains children’s products.

And for pharmacies, which may only offer topical or sublingual products, all products must be in an area not accessible to the general public. Only a licensed pharmacist or employee directly under their supervision (even if under 21 years of age) may conduct sales for the relevant hemp products.

Step 7: Meet Certain Record Keeping and Reporting Requirements

Licensed retailers must keep and preserve all records related to consumable hemp products for three years. This requirement includes invoices, cancelled checks, and other documentation related to the purchase, sale, exchange, or receipt of all consumable hemp products. And ABC has significant authority to ensure recordkeeping requirements are met. Specifically, ABC “may enter upon the premises of any licensee at any time of the day or night . . . for the detection of violations of this chapter.”

Furthermore, retailers must submit a consolidated report on the last day of the month following the month of receipt or sale of all receipts and sales of consumable hemp products made to customers during the preceding month.

Conclusion

We are less than a month from the implementation of Alabama’s new hemp law, and I get the sense most hemp operators are behind the curve when it comes to understanding and preparing for these significant changes. Those people would be wise to get prepared quickly, because if history is a guide, we can expect law enforcement raids as soon as January 1. Please let us know if we can help you prepare for enactment of the new law.

Thanks for stopping by.

What to Watch: Continued DTC Advertising Enforcement

Just before Thanksgiving, the Food and Drug Administration’s (“FDA’s”) Office of Prescription Drug Promotion (“OPDP”) silently published three untitled letters, furthering this administration’s promise to crack down on direct-to-consumer (“DTC”) prescription drug advertising.[1] The letters (which we’ll call “Letter 1,” “Letter 2,” and “Letter 3”) addressed familiar enforcement themes, such as omission or minimization of risk information, ad presentation and form, and promotion consistent with FDA-required labeling (“CFL”). The letters appeared to have been leftovers from the shutdown, dated from earlier in September when the crackdown was in full swing. This is why we refresh these pages daily.

Letter 1OPDP found a television ad for an oral cardiovascular medication misleading and, therefore, misbranded under the Food, Drug, and Cosmetics Act (“FDCA”), because it overstated the drug’s approved indication. Specifically, the ad represented that the drug was approved on the single endpoint of “reducing the risk of cardiovascular death” in adults with chronic kidney disease (“CDK”) or heart failure (“HF”); however, the drug’s FDA-approved Prescribing Information indicates that approval was based on more granular composite endpoints, including reduction of sustained estimated glomerular filtration rate decline, progression to end-stage kidney disease, cardiovascular or renal death in CDK patients, and reduction of cardiovascular death, hospital visits, or urgent visits in HF patients.

Letter 2OPDP found a webpage for a ketamine injection intended for surgical pain management misleading and, therefore, misbranded under the FDCA, because it promoted the benefits of the drug without communicating risk information and overstated the drug’s approved indication. Specifically, the webpage promoted the drug for pain management in all surgical and diagnostic procedures, but failed to communicate important use limitations from the drug’s FDA-approved Prescribing Information, including an exclusion for procedures requiring skeletal muscle relaxation and specifications that it be used before and/or as a supplement to other general anesthetic agents. OPDP found this especially concerning because this particular drug is a generic and the webpage misleadingly suggested that its intended use was broader than that of its reference listed drug. To wrap up its letter, OPDP also cited the company for failing to submit a copy of the webpage under a Form FDA-2253 prior to initial publication, as required by FDA regulations.

Letter 3OPDP found a television ad for an oral seizure medication misleading and, therefore, misbranded under the FDCA, because it promoted the benefits of the drug with minimized presentation of risk information. Specifically, the ad (i) excluded a warning concerning the risk of liver injury from the drug’s Prescribing Information; (ii) failed to disclose the risk of problems with the heart’s electrical system, as included in the drug’s FDA-approved labeling, despite the fact that the ad stated “[s]erious, life threatening allergic reactions or rash can occur, which may affect the liver, other organs, body parts, or blood cells, as can problems with the heart.” Additionally, certain material information from the drug’s major statement (i.e. the presentation of major risks required for all pharmaceutical television ads) was included in SUPERS but not in the corresponding audio, even though benefits were presented via SUPERS and audio.

FOOTNOTES

[1] See our post on OPDP’s previous enforcement under this administration.

Seeking Grace- Pursuing Method of Treatment Claims in View of Clinical Trial Related Disclosures

I. Background

Method of treatment patents based on Phase II and Phase III clinical trial protocols are routinely pursued to extend patent exclusivity and strategically build a patent portfolio for a drug asset. The claims of these “later-generation” method of treatment patents recite salient features of the Phase II or Phase III clinical trial protocol including patient populations, dosage amounts, dosing regimens, and efficacy outcome measurements. This is done for good reason, as the salient features of the study protocol often appear on the drug label, sometimes as part of explicit active steps.

For a new chemical entity (NCE), a later-generation method of treatment patent provides additional patent term, sometimes years beyond the patent term of the earlier-generation patents, i.e., foundational patents providing composition of matter and/or broad method of treatment exclusivity.

For repurposed drugs or novel dosing protocols, method of treatment patents based on Phase II or Phase III clinical trial study protocols may provide the only meaningful source of patent exclusivity, e.g., if the compound is known and the composition of matter patent has expired or is soon to expire.

Conventional wisdom dictates filing a patent application based on a Phase II or Phase III clinical trial protocol prior to a public disclosure of the study to avoid creation of prior art that can preclude patentability of the method of treatment claims, particularly outside the U.S.[1] Given the strategic importance of later-generation method of treatment patents, care should be taken to understand the timing of any public disclosures relating to the clinical trial and to plan patent application filings accordingly.

One such clinical trial related public disclosure is the posting of the innovator’s clinical trial protocol to ClinicalTrials.gov (“CTG”) as a so-called “study record.”[2] Posting of the study record is part of the U.S.’s well-intentioned effort to conduct human clinical trials with transparency to, inter alia, build public trust in clinical research and help patients find trials for which they might be eligible to participate. Innovators are to submit clinical trial study protocols to FDA no later than 21 days after the first patient is enrolled in the trial[3], and the study record will be posted not later than 30 days after submission[4][5]. Given these deadlines, it is typically not possible to predict the exact day a study record becomes public on CTG. Such an “un-docketable” deadline, unlike the firm date of an expected journal article publication or public symposium, has – perhaps unsurprisingly – led to a fact pattern where a study record is posted to CTG before a corresponding method of treatment patent application is filed.

II. Use of the § 102(b)(1)(A) exception

Clinical trials themselves are not considered a prior public use under 35 U.S.C. § 102(a)(1).[6] CTG study records and other clinical trial related disclosures, however, are considered printed publications and/or “otherwise available to the public” under §§ 102(a)(1) if made before the effective filing date of the patent application. Such clinical trial related disclosures can therefore be used to reject a later-filed patent application’s method of treatment claims as anticipated under 35 U.S.C. § 102(a)(1) and/or obvious under 35 U.S.C. § 103.

In the event a CTG study record or related disclosure becomes publicly available prior to filing a corresponding U.S. method of treatment patent application, the grace period exception under § 102(b)(1)(A) may be invoked to disqualify the disclosure under § 102(a)(1) – provided the disclosure is made one year or less before the effective filing date of the application. Procedurally, should an Examiner make a rejection under 35 U.S.C. §§ 102(a)(1) and/or 103 based on a CTG study record or related disclosure, Applicant can invoke the grace period by submitting a declaration under 37 CFR § 1.130 (“Rule 130”) establishing that the disclosure was made by the inventor or joint inventors and requesting removal of the CTG study record or related disclosure as prior art.

While submission of the Rule 130 declaration seems straightforward, a recent PTAB example, Murray & Poole Enterprises Ltd. v. Institut de Cardiologie de Montreal[7] is illustrative of potential traps. Institut de Cardiologie de Montreal (ICM) attempted to remove “Bouabdallaoui” as prior art by invoking the grace period exception under § 102(b)(1)(A). Bouabdallaoui was published within the one-year grace period and expanded on the results of the “COLCOT” CTG study record. Bouabdallaoui listed seven authors, the second of whom, Dr. Tardif, was the sole inventor on ICM’s patent. The board articulated that invocation of the grace period hinged on whether the declaration of Dr. Tardif provided sufficient information to conclude that Bouabdallaoui was not “by another.”[8] Dr. Tardif’s declaration explained the working relationship with only one co-author (Bouabdallaoui), as inter alia, acknowledgement of Bouabdallaoui’s assistance in conducting the clinical trial and to provide a first author publication. Dr. Tardif’s declaration also described the scope of the COLCOT multi-center clinical trial and ICM’s status as the sponsor, supported by agreements between some of the centers and the sponsor. The board pointed out that only a subset of center-sponsor agreements was provided and, among the agreements provided, none listed Dr. Tardif as the principal investigator.[9] Ultimately, in its decision of institution, the board found that Dr. Tardif’s declaration was insufficient to disqualify Bouabdallaoui as prior art.[10]

As Murray demonstrates, all differences between the authors of the clinical trial related disclosure and inventors on the patent application should be thoroughly explained. Declarations from any superfluous authors, i.e., non-inventors, disclaiming their contribution to the subject matter relied on in making the prior art rejection may help establish that the clinical trial related disclosure is not “by another.” CTG study records, unlike typical publications, list only the sponsor of a clinical trial, not specific individuals responsible for designing the study. Nonetheless, the inventor(s) can attest to the CTG study record as their own work in a declaration. Supporting documentation clearly tying the inventor(s) to the CTG study record, e.g., by naming the inventor(s) as the principal investigator(s), can also be provided.

III. International grace period provisions and filing strategies

In addition to the U.S., several foreign jurisdictions also provide a grace period. While not exhaustive, Table 1 summarizes grace period availability in commonly filed foreign jurisdictions, application filing timing, and whether proactive steps should be taken to make use of the grace period. Practitioners should work closely with local counsel to understand nuanced national requirements and timing to properly rely on each country’s available grace period.

Table 1

Country

Grace Period Available

Time to file application (from disclosure)

Type of first application that should be filed

Can the first application serve as priority document…†

Notes

AU

Yes

12 months

AU Standard Application or PCT

Yes (for PCT)

No proactive steps required.

BR

Yes

12 months

U.S. Provisional, BR, or PCT

Yes

No proactive steps required.

CA

Yes

12 months

CA or PCT

No

No proactive steps required.

CN

No

—

—

CTG disclosure does not qualify for the grace period.

EP

No

—

—

CTG disclosure does not qualify for the grace period.

JP

Yes

12 months

JP or PCT

No

Within 30 days of filing the JP national application or JP national phase entry, a certificate must be filed describing several features of the public disclosure.

KR

Yes

12 months

KR or PCT

Yes, but only if priority filing is (a) a PCT application designating only KR or (b) a direct KR application

Evidentiary documents must be submitted proving the applicant/inventor’s disclosure and showing (i) the date and type of the disclosure, (ii) the disclosing party, and (iii) the content of the disclosure.

MX

Yes

12 months

U.S. Provisional, MX, or PCT

Yes

The date of the public disclosure must be included on a form when filing the MX national application or MX national phase entry of the PCT.

PH

Yes

12 months

U.S. Provisional, PH, or PCT

Yes

No proactive steps required.

SG

Yes

12 months

PCT

No

No proactive steps required.

TW

Yes

12 months

TW

No

No proactive steps required.

U.S.

Yes

12 months

U.S. Provisional or PCT

Yes

No proactive steps required.

† for a PCT or other application filed after the grace period that benefits from the grace period?

Like the U.S., Australia, Brazil, Canada, Japan, Mexico, the Philippines, South Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan all provide grace periods for CTG study records and related disclosures within 12 months of a first patent application’s filing date. They differ, however, with respect to whether the first patent application can serve as a priority document to a later-filed application, e.g., a PCT application, where the national stage application of the PCT application will also be eligible to benefit from the grace period. Certain jurisdictions, e.g., China and Europe, effectively do not have grace periods applicable to CTG study records or related disclosures.

In view of these distinctions, one can envisage complex potential filing strategies depending on international filing priorities.

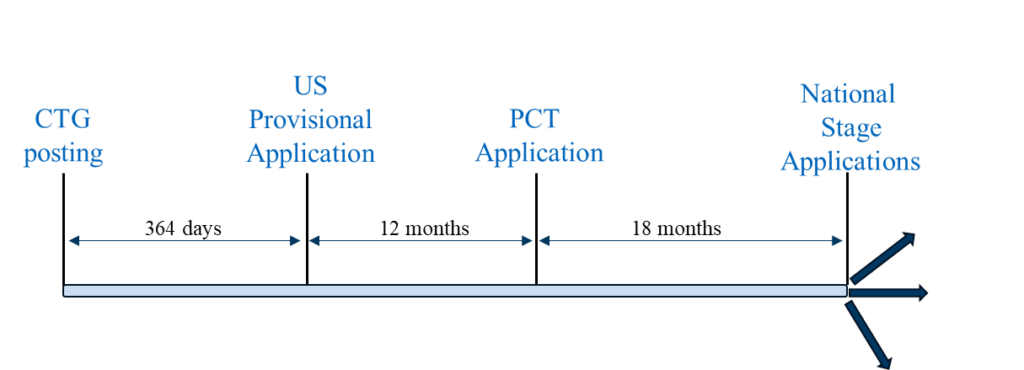

Scenario 1 is a “typical” filing strategy where a U.S. provisional application is the first-filed application in the family. This filing strategy can be followed to pursue patent coverage in countries where a U.S. provisional application filed within 12 months of the CTG study record or related disclosure can serve as a priority document to a PCT application filed 12 months after the U.S. provisional application, and the national phase applications of the PCT application are eligible to benefit from the grace period based on the U.S. provisional application’s filing date. Representative countries in which this filing strategy can be utilized include the U.S., Brazil, Mexico, and the Philippines.

Filing Scenario 1

Scenario 1 can also be followed in countries that actually or effectively lack grace periods (e.g., China and Europe). To overcome the absolute novelty bar in China, possible aspects of the planned commercial methods that are not disclosed in the clinical trial related disclosure can be included in the U.S. provisional and/or PCT application. In Europe, CTG study records or announcements regarding ongoing trials not considered to be novelty destroying, although they can be used in an inventive step analysis.[11] For guidance on the implications of clinical trials as prior art in Europe, we direct the reader to the Spring 2024 AIPLA Chemical Practice Committee’s informative article on this very topic.[12]

Scenario 2 can be followed in countries where a PCT or non-PCT country national application must be filed within one year of the public disclosure for the national application to be eligible to benefit from a grace period. Representative countries in which this strategy can be utilized include Australia, Canada, Japan, Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan.

Filing Scenario 2

Scenario 1 provides two potential advantages compared to (a) a more conservative filing strategy where the U.S. provisional application is filed prior to the CTG study record posting and (b) Scenario 2: (1) maximum time for generating clinical trial results which, if available, can be included in the PCT application, and (2) the potential for maximum patent term.

Scenario 2 does not offer the benefit of an extended duration between CTG study record posting and national or PCT application filing. As such, results of the clinical trial are generally less likely to be available by the time a PCT application or non-PCT country national application is filed. However, many of the above-mentioned countries permit post-filing data during prosecution by which clinical trial results can be presented.[13]

Scenario 3 combines Scenario 1 and Scenario 2 into a unified filing strategy. First, a U.S. provisional application (following Scenario 1), a first PCT application (PCT1) (following Scenario 2), and non-PCT country national application(s) (following Scenario 2) are filed on the same day and within one year of the CTG study record posting. Prior to filing any applications outside the U.S., a foreign filing license should be considered and, if necessary, obtained. PCT1 can be nationalized in the jurisdictions with stricter grace period requirements outlined above for Scenario 2.

Filing Scenario 3

A second PCT application (PCT2) claiming priority to the U.S. provisional application can then be filed on the 12-month Convention date for the U.S. provisional application that includes the results of the clinical trial, if available. PCT2 can be nationalized in the jurisdictions with more relaxed grace period requirements as outlined above for Scenario 1.

This bespoke approach maximizes the potential benefits of grace periods, where available, while accounting for inclusion of clinical trial results data (either in PCT2 or as post-filing data during national stage application prosecution). The result is improved chances of obtaining method of treatment coverage and longer patent term.

IV. Conclusion

CTG posting of a Phase II or Phase III study record or a related public disclosure does not inevitably preclude patentability of method of treatment claims in a later-filed patent application based on the clinical trial protocol. A surprising number of jurisdictions provide grace periods by which a CTG study record or related disclosure can be removed as prior art if a patent application is filed within one year of the disclosure. However, the type of patent application that must be filed within one year varies by jurisdiction, thereby leading to complex filing strategies. In the U.S., to exclude CTG study records using the § 102(b)(1)(A) exception, practitioners should carefully draft Rule 130 declarations that unambiguously tie the inventor(s) of the patent application to the sponsor and principal investigator(s) of the clinical trial. Similarly, Rule 130 declarations to exclude clinical trial related disclosures using the § 102(b)(1)(A) exception should unambiguously explain any and all differences between the author(s) of the disclosure and the inventor(s) of the claimed subject matter.

[1] Most ex-US jurisdictions do not permit “method of treatment” claims per se, although such claims can be reformulated in accordance with local practice, e.g., as Swiss-type claims and/or purpose-limited compounds for use-type claims.

[2] 42 U.S.C. § 282(j)(2)(A)

[3] 42 U.S.C. § 282(j)(2)(C)

[4] 42 U.S.C. § 282(j)(2)(D)

[5] Changes to the clinical trial, including changes to the protocol, are also posted to CTG by the same mechanism such that multiple study records are typically available on CTG for a given clinical trial.

[6] See, e.g., Sanofi v. Glenmark Pharms, Inc., USA, 204 F. Supp. 3d 665 (D. Del. 2016), aff’d sub nom., Sanofi v. Watson Lab’ys Inc., 875 F.3d 636 (Fed. Cir. 2017) (A patent on a method of using dronedarone in treating patients was not ready for patenting before the critical date and thus not a public use); In Re Omeprazole Patent Litigation, 536 F.3d 1361 (Fed. Cir. 2008) (A Phase III clinical trial was not a public use because the invention had not been reduced to practice and therefore was not ready for patenting).

[7] IPR2023-01064, Paper 9 (P.T.A.B., Jan. 16, 2024).

[8] Id., page 54.

[9] Id., page 55.

[10] Id., page 56.

[11] T 158/96, T 715/03, T 1859/08 and T 2506/12

[12] Dr. Holger Tostmann, Newsletter of the AIPLA Chemical Practice Committee, Spring 2024, Volume 12, Issue I, p. 24.

[13] In Canada, utility is established by demonstration or “sound prediction” at the time the application is filed.

The 2026 OPPS Final Rule: Hospitals Now at a Decision Point Regarding Drug Acquisition Cost Survey

The 2026 Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) final rule (the Final Rule), released by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) on 21 November 2025 places hospitals, especially 340B covered entities, in a quandary. Under OPPS, hospitals are currently paid for separately payable drugs at average sales price (ASP) plus 6%. CMS has previously sought to reduce that reimbursement, specifically targeting 340B covered entities, but the American Hospital Association (AHA) and others successfully overturned that policy at the Supreme Court (American Hospital Association v. Becerra). The Final Rule reflects CMS’s next attempt to achieve the same result. Specifically, while the Supreme Court faulted CMS’s payment cuts to 340B covered entities due to the lack of a statutorily mandated drug acquisition cost survey, CMS has now finalized plans to conduct such a survey. The question for hospitals is whether to complete that survey. CMS does not reference statutory tools that permit it to penalize hospitals that opt not to complete the survey but instead has resorted to saber-rattling, devising other ways to potentially reduce reimbursement to nonresponding hospitals not explicitly found within the statute itself. Thus, hospitals need to compare the consequences of volunteering to take the survey, on the one hand, with the probable consequences of declining to take the survey, on the other, and then decide if they will complete it or forego it.

CMS’s Policy Is Governed by the Applicable Statute

When CMS determines the rate for separately payable drugs in its annual rulemaking, the OPPS statute gives CMS two options for setting these rates:

The agency can conduct a survey of hospitals’ drug acquisition costs and set reimbursement rates taking the survey into account; for this option, reimbursement rates may vary by hospital group.

Absent a survey meeting specific statutory requirements, CMS must set reimbursement rates based on “the average price” charged by manufacturers for the drug as calculated and adjusted by CMS; for this option, reimbursement rates may not vary across different hospital groups.

If CMS chooses to conduct a drug acquisition cost survey, the statute requires the survey include “a large sample of hospitals that is sufficient to generate a statistically significant estimate of the average hospital acquisition cost for each [covered drug].” CMS may then vary reimbursement rates by hospital group based on “relevant characteristics,” upon “taking into account the hospital acquisition cost survey data.”

Reduced OPPS Reimbursement Rates for 340B Hospitals

Historically, CMS has not conducted the required OPPS survey, and, prior to 2018, CMS reimbursed all hospitals for OPPS drugs based on ASP plus 6%. On 13 November 2017 however, CMS issued the 2018 OPPS final rule, reducing the reimbursement rate for OPPS-covered drugs to ASP minus 22.5% for 340B covered entities. CMS did not conduct a survey in implementing the new 340B-specific reimbursement rates, resulting in a challenge by AHA and others. On 15 June 2022, in American Hospital Association v. Becerra, the US Supreme Court unanimously held that the 340B covered entity-specific rate was unlawful because CMS was required to conduct a valid acquisition cost survey before targeting 340B hospitals for reduced reimbursement. American Hospital Association v. Becerra, 596 U.S. 724 (2022). To remedy the unlawful cuts, CMS paid a lump sum to bring previously adjudicated claims to the lawful ASP plus 6% reimbursement rate and has reimbursed all 340B hospital claims at ASP plus 6% moving forward.

OPPS Survey Confirmed for Calendar Year 2026

The 2026 OPPS Final Rule confirms that CMS intends to vary OPPS drug reimbursement across certain hospital groups by conducting the survey mandated by statute. CMS indicates it is not limiting the survey to varying reimbursement based on 340B status alone and includes examples of other characteristics that may be used to vary reimbursement (i.e., hospital size, location, urban vs. rural status, and teaching hospital status). CMS intends for the survey to be completed in time to inform reimbursement rates for the 2027 OPPS rule.

CMS is aware that hospitals are considering whether to respond to the survey. CMS agrees that the statute itself does not mandate specific consequences on hospitals for failing to respond but nevertheless believes that the statute implicitly imposes the obligation on hospitals to complete the survey. To avoid a situation where hospitals rationally decide not to take on the burden of completing the survey, CMS resorts to what could only be described as threatening nonresponders. CMS claims that the lack of a response is still “meaningful data” that can drive payment decisions. For example, CMS might take failure to respond to the survey as confirmation that a hospital does not have meaningful additional costs, and, as such, the hospital’s drug costs should not be paid separately but rather should be packaged into the payment for the associated service. Another potential alternative CMS is considering is to attribute to such a hospital the lowest acquisition cost reported by a similarly situated hospital. CMS has also suggested that it might look at supplemental data from other sources, even though there is no provision in the statute for such an approach. Ironically, CMS’s consideration of supplemental information exclusively when setting the ASP minus 22.5% rate was a main factor considered by the Supreme Court in the American Hospital Association v. Becerra decision. CMS has suggested that it would be premature, however, to commit to a specific penalty for failure to complete the survey until the survey process is completed.

Some may find it hard to square CMS’s proposed penalties with the text of the statute. The statute requires CMS to “tak[e] into account the hospital acquisition cost survey data” when setting the payment rate for separately payable drugs. When CMS discerns “relevant characteristics” in data that help explain correlations, CMS can vary reimbursement for a specific group. A nonresponding hospital, in contrast, demonstrates the absence of data, from which no pattern can be discerned. Arguably, opting not to respond is more properly viewed as an “action” and not a “characteristic.” Many hospitals may conclude that, just as with American Hospital Association v. Becerra, CMS is likewise interpreting the statute to reach an outcome, rather than adhering to the statute’s plain meaning. Yet hospitals must also keep in mind that nothing prevents CMS from implementing a policy that is ultimately unlawful, resulting in the imposition of penalties for some period of time until a court overturns any policy that exceeds CMS’s statutory authority.

Hospitals Face a Difficult Choice

Notwithstanding all of CMS’s protestations to the contrary, completing the survey will require significant effort. A lot of the work required cannot be automated and will be manual, given the pervasive nature of lagged discounts, and will require intricate calculations. For 340B covered entities, there is additionally the fear that the data will be used to cut much-needed reimbursement. A rational hospital might opt not to participate if it did not believe that there would be significant negative consequences. The issue a hospital will face is determining what its peers will do. If the response rate is below what is statistically necessary, then the plain meaning of the statute does not allow CMS to use the data to revise its payment policies. However, each hospital will need to decide if it individually is willing to risk the potential consequences CMS set forth in the Final Rule for not responding. In other words, CMS has created a “prisoner’s dilemma.” Each hospital will need to decide whether to minimize its own exposure to the proposed negative consequences by responding or take a chance that the survey is invalidated by an industrywide inadequate response rate.

Some actions available to hospitals will be:

Respond fully;

Disregard the survey; or

Respond to the survey only to state that the hospitals’ costs are not minimal, but that the hardships in responding preclude the full response CMS is seeking. By doing so, the hospital could thwart CMS’s objective of attributing zero cost to a nonresponding hospital.

Of course, most hospitals will not consider this to be an easy decision. Hospitals, especially 340B covered entities, should consult with their advisors and peers to make the decision that is most appropriate for them.

What 340B Hospitals Need to Know About CMS’s CY 2026 OPPS Final Rule

Key Takeaways

CMS launches Drug Acquisition Cost Survey beginning Jan. 1, 2026. OPPS hospitals must submit NDC-level pricing data for both 340B and non-340B drugs, which CMS will use to inform CY 2027 reimbursement policy.

Hospitals must prepare for significant operational and legal risks. Nonparticipation in the survey could lead to drug packaging and reimbursement loss, and hospitals should begin data validation and site-of-service planning now.

Site-neutral payment cuts for drug administration services take effect in CY 2026. Excepted off-campus departments will be paid at the PFS rate — 60% lower than OPPS — affecting 61 HCPCS codes tied to infusion and injection services.

CMS’s recently published CY 2026 OPPS Final Rule will affect 340B covered entities in two key ways starting Jan. 1, 2026. First, CMS will conduct a Drug Acquisition Cost Survey to collect NDC-level pricing data on separately payable 340B and non-340B drugs from all hospitals paid under the OPPS. Second, CMS will apply physician fee schedule (PFS) reimbursement rates to drug administration HCPCS codes furnished at provider-based sites considered excepted under Section 603 of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015.

Payment reductions for drug administration codes will have immediate financial consequences, and CMS’s Acquisition Cost Survey could lead to substantial reimbursement changes. 340B covered entities should carefully evaluate how they plan to respond, as CMS outlined several proposals for hospitals that decline to participate.

OPPS Drug Acquisition Cost Survey

CMS intends to survey all hospitals for detailed acquisition cost data across nearly 2,300 NDCs. CMS intends to use this data to inform OPPS drug payment policy beginning with the CY 2027 OPPS/ASC Proposed Rule. Given the CMS’s prior unlawful attempt to reduce drug reimbursement in 2018 and the Supreme Court’s 2022 decision overturning that effort, the Final Rule signals a renewed push to justify payment cuts for separately payable drugs. The language clearly suggests that 340B covered entities may be a prime target.

Survey Scope and Requirements: What Providers Need to Know

The survey will impose a significant data burden on hospitals, particularly for 340B covered entities. Below is a summary of key requirements and timelines:

Who: All OPPS hospitals must provide requested survey data (note this excludes CAHs since they are not paid under OPPS).

What: Acquisition cost at the NDC level, including discounts directly applicable to an individual NDC and also those discounts not necessarily linked to a single NDC (e.g., discount linked to invoice, prompt pay discounts, wholesaler discounts).

CMS is asking hospitals to separately list their acquisition costs for drug NDCs acquired through the 340B program and those drug NDCs acquired outside of the 340B program.

HRSA’s 340B pilot program is out of scope of this survey.

Hospitals must provide data from July 1, 2024, to June 30, 2025.

When: Starting early 2026.

Considering CMS plans to complete the survey in time to inform the CY 2027 OPPS/ASC proposed rule, data will likely be due by March 31, 2026.

Where and How: CMS will launch a portal on Jan. 1, 2026, that hospitals must register with to upload drug acquisition cost data.

CMS will host webinars on Dec. 9, 2025, and Dec. 11, 2025, to provide an overview of the survey and data submission. Providers should plan to attend. Details and other resources can be found here.

CMS has published a Draft Survey Template that offers some insight into the required data and formatting.

CMS Cuts Reimbursement for Drug Administration Codes at Excepted Off-Campus Sites

Beginning in CY 2026, CMS will expand its site-neutral payment policy to significantly reduce Medicare reimbursement for drug administration services furnished in excepted provider-based hospital outpatient departments (HOPDs). Although these HOPDs were historically “grandfathered” or “excepted” under Section 603 of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 — meaning they could continue to be paid at the higher OPPS rate — CMS is using its authority to curb what it views as inappropriate increases in the volume of outpatient services by reducing the payment differential for the drug administration component (not the drug itself but see above Acquisition Cost Survey discussion). As a result, drug administration services at excepted HOPDs will be paid at the PFS equivalent rate (40% of OPPS), rather than the full OPPS hospital rate.

This policy also signals CMS’s increasing willingness to expand site-neutral payment reforms, suggesting additional future pressure on outpatient reimbursement models, including for 340B hospitals.

For all hospitals paid under the OPPS that provide complex infusion and injection services — including 340B covered entities — this change represents a substantial payment reduction for services provided in excepted HOPDs. CMS estimates a $280 million overall decrease in OPPS spending in CY 2026 from this provision. While the policy does not change payment for the drug itself, it directly affects the payment intended to reimburse hospitals for the cost of the facility, nursing and other staffing costs, supplies, drug preparation and storage, and other overhead. The PFS equivalent rate for drug administration services will represent a 60% reduction of the OPPS rate. This change impacts APCs 5691, 5692, 5693 and 5694, which represent 61 HCPCS.

Key Considerations and Risks for All Hospitals

Hospitals should take proactive steps to prepare for both the drug acquisition survey and the payment changes tied to provider-based drug administration services.

Hospitals should begin validating their ability to extract 340B vs. non‑340B acquisition detail at the NDC level using the Draft Survey Template. The burden will be material, since it includes roughly 2,300 NDCs and requires substantial analysis to incorporate various discounts offered to providers.

Though CMS does not explicitly require participation with an enforcement mechanism, participation is effectively mandatory. Hospitals that do not report their drug acquisition costs may be viewed as lacking meaningful additional, marginal costs related to their acquisition of the drugs and CMS may determine the drugs costs should not be paid separately but should be packaged. Although CMS may lack statutory authority to engage in such rate setting, all hospitals should carefully consider this dialogue and associated risks when considering a non-response.

Certain trade associations are likely looking closely at the survey and associated burdens, and they could coordinate a challenge of the survey. We would also expect legal challenges to resulting rates if stakeholders determine that the survey is inadequate.

Hospitals should also assess the financial impact of CMS’s site-neutral payment policy for drug administration services. Hospitals should evaluate service mix, site-of-service utilization, and potential operational shifts, such as relocating services to on-campus departments or affiliated physician office settings, to mitigate the impact of these payment reductions.

Prop 65 Pulse- October 2025 Bounty Hunter Plaintiff Claims

California’s Proposition 65 (“Prop. 65”), the Safe Drinking Water and Toxic Enforcement Act of 1986, requires, among other things, sellers of products to provide a “clear and reasonable warning” if use of the product results in a knowing and intentional exposure to one of more than 900 different chemicals “known to the State of California” to cause cancer or reproductive toxicity, which are included on The Proposition 65 List. For additional background information, see the Special Focus article, California’s Proposition 65: A Regulatory Conundrum.

Because Prop. 65 permits enforcement of the law by private individuals (the so-called bounty hunter provision), this section of the statute has long been a source of significant claims and litigation in California. It has also gone a long way in helping to create a plaintiff’s bar that specializes in such lawsuits. This is because the statute allows recovery of attorney’s fees, in addition to the imposition of civil penalties as high as $2,500 per day per violation. Thus, the costs of litigation and settlement can be substantial.

The purpose of Keller and Heckman’s latest publication, Prop 65 Pulse, is to provide our readers with an idea of the ongoing trends in bounty hunter activity.

In October of 2025, product manufacturers, distributors, and retailers were the targets of 590 new Notices of Violation (“Notices”) and amended Notices, alleging a violation of Prop. 65 for failure to provide a warning for their products. This was based on the alleged presence of the following chemicals in these products. Noteworthy trends and categories from new Notices sent in October 2025 are excerpted and discussed below. A complete list of all new and amended Notices sent in October 2025 can be found on the California Attorney General’s website, located here: 60-Day Notice Search.

Food and Drug

Product Category

Notice(s)

Alleged Chemicals

Dietary Supplements: Notices include smoothie powder, collagen powder, and nutrition shakes

80+

Notices

Cadmium, Lead and Lead Compounds

Assorted Prepared Food and Snacks: Notices include sunflower seeds, cookies, chips, and soup

63

Notices

Cadmium, Lead and Lead Compounds, Mercury

Seafood: Notices include shrimp sauce, dried squid, and chopped clams

42

Notices

Cadmium and Cadmium Compounds, Lead and Lead Compounds, Mercury and Mercury Compounds

Fruits and Vegetables: Notices include carrots, cherries, and dried apricots

21

Notices

Cadmium, Lead and Lead Compounds

Spices, Sauces, and Tea: Notices include matcha green tea, ground turmeric, and salsa

17

Notices

Lead and Lead Compounds

Noodles, Pasta, and Grains: Notices include brown basmati rice, penne pasta, and ramen noodles

11

Notices

Cadmium, Lead and Lead Compounds

Plant-Based Protein Powder and Superfood Blend

5

Notices

Lead and Lead Compounds, Perfluorononanoic Acid (PFNA), Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA)

Consumer Products

Product Category

Notice(s)

Alleged Chemicals

Receipts, Thermal Receipt Paper, and Energy Drink

200+

Notices

Bisphenol S (BPS)

Household Items: Notices include baskets, plant holders, and tabletops

33

Notices

Di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP),

Diethanolamine, Lead,

Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS), PFOA

Glass, Ceramics, and Other Housewares: Notices include mugs, trays, dishes, and pots

30

Notices

Lead

Bags and Cases

24

Notices

DEHP, Diisononyl phthalate (DINP)

Household Items and Tools: Notices include drain stoppers, hose splitters, and USB cords

12

Notices

Lead

Clothing: Notices include boots, heels, shirts, and pants

12

Notices

DEHP, PFOA

Household Items and Sports Gear: Notices include dumbbells, skipping rope, and kettlebells

8

Notices

DEHP, DINP, Lead, Di-n-butyl phthalate (DBP)

DOJ Ramps Up Antitrust Enforcement in Agriculture Industry

Earlier this year, Foley & Lardner reported on the Department of Justice (“DOJ”) Antitrust Division’s announced plans to ramp up civil and criminal antitrust enforcement in the agriculture sector. Recent actions taken by the DOJ and statements made by leading officials in the Antitrust Division show they are making good on those promises.

Most recently, Assistant Attorney General Gail Slater announced this past Wednesday that DOJ enforcers have initiated several investigations aimed at the meatpacking industry—which she called a “priority” for the DOJ. Earlier this month, U.S. Attorney General Pam Bondi similarly announced that a joint investigation into the industry by the DOJ Antitrust Division and the Department of Agriculture was underway. Both announcements came shortly on the heels of November 7, 2025, Truth Social posts from President Trump, where he called on the DOJ to “immediately begin an investigation” into the major meat processors. The President’s exhortation may have resulted from increasing commentary about rising consumer costs for beef products. The ensuing investigations could be expansive and extend well beyond the companies singled out by the President.

The DOJ has signaled its intended focus on the agriculture industry through other means too. The Antitrust Division and the Department of Agriculture recently executed a Memorandum of Understanding to facilitate the agencies’ cooperation in “monitoring competitive conditions in the agricultural marketplace.” Additionally, the DOJ has initiated large-scale investigations in the industry in recent years, such as the 2021 investigation into the broiler chicken industry, and brought several large agricultural antitrust enforcement actions, including the still-ongoing United States v. Agri Stats, Inc. There, the DOJ alleges that Agri Stats violated Section 1 of the Sherman Act by collecting, utilizing, and sharing competitively sensitive price, cost, and output information among competing meat processors. Given the role of Agri Stats in private antitrust litigation against broiler chicken producers, the DOJ suit highlights the need for agriculture companies to diligently monitor their use of third-party aggregate benchmarking services.

These recent developments have important implications for companies in the agriculture industry (and beyond). They are likely to see a continued uptick in DOJ investigations and resulting criminal and civil enforcement cases. It is also reasonable to expect a flurry of follow-on civil litigation (including class actions) initiated by private plaintiffs. Coming into an election year, these matters may also create pressure for Congressional investigations and hearings. Companies in the agriculture industry should be mindful of this heightened legal, and potentially political, scrutiny.

Significant Hemp Restrictions Included in Funding Bill

On November 12, 2025, the Agriculture, Rural Development, Food and Drug Administration, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act was signed, as part of the reopening the federal government. In addition to a $26 billion spending package, language was included in the bill that would severely limit hemp products, essentially undoing the hemp industry framework established under the 2018 Farm Bill.

The Act revises the “hemp” definition to limit the material to “a total tetrahydrocannabinols [THC] concentration (including tetrahydrocannabinolic acid) of not more than 0.3 percent on a dry weight basis” (no longer focusing on just the delta-9 THC level).

The Act also prohibits final hemp-derived cannabinoid products from containing the following: (1) cannabinoids that are not capable of being naturally produced by a cannabis plant; (2) cannabinoids that are capable of being naturally produced by a cannabis plant and are synthesized or manufactured outside the plant; and (3) more than 0.4 milligrams combined total per container of (a) total THCs (including tetrahydrocannabinolic acid) and (b) “any other cannabinoids that have similar effects (or are marketed to have similar effects) on humans or animals as a tetrahydrocannabinol.”

The revisions are expected to drastically limit (if not effectively eliminate) the availability of hemp-derived cannabinoid products (including those containing cannabidiol (CBD)) given the new “hemp” criteria.

Within 90 days of enactment, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is to work with other agencies to publish a list of: (1) all cannabinoids known to be capable of being naturally produced by a Cannabis sativa L. plant; (2) all THC class cannabinoids known to be naturally occurring the plant; and (3) all other known cannabinoids with similar effects to, or marketed to have similar effects to, THC class cannabinoids.

These provisions are scheduled to take effect on November 12, 2026, at which point many currently-permitted products would become prohibited controlled substances. The cannabis products industry has a limited window in which to pursue a new legislative framework.

The Continuing Impact of Tariffs, Trade Disruptions, and Federal Government Reopening on the U.S. Soybean Sector

The U.S. soybean industry remains a focal point in the intersection of American agriculture, global trade policy, and federal regulatory action. Ongoing trade tensions — particularly between the United States and China — have reshaped the global soybean value chain, while rising input costs, labor constraints, and regulatory uncertainty create additional pressures for farmers. In recent months, attention has turned toward how the reopening of the federal government — after extended funding uncertainty — may influence agricultural markets, regulatory decisions, and the broader operating environment for soybean farmers. The combined effect of trade policy, regulatory backlogs, and supply chain disruptions have created a complex landscape for growers heading into the 2026 planting season.

The U.S.-China trade dispute remains the most significant driver of soybean volatility. China historically purchased more than half of all U.S. soybean exports. Retaliatory tariffs and geopolitical friction have, however, caused dramatic declines. Recent U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) data show that U.S. soybean exports to China in 2025 (to date) totaled around 218 million bushels, down from nearly one billion bushels the prior year. Investigative reporting has also raised questions about whether China will meet its announced purchase commitments. Despite high-profile White House claims of pending deals, reporters found little empirical evidence of large-scale Chinese purchases materializing. Attempts by trade officials to secure new buyers — including recent diplomatic missions to Latin America, Africa, and Southeast Asia — have been met with cautious optimism but limited concrete commitments.

Farmer-facing organizations, including Farm Action, have also argued that trade instability exacerbates existing market concentration and vulnerabilities tied to soybean monoculture. Tariffs have increased the cost of imported fertilizers, chemicals, and machinery parts. This is particularly pronounced in the crop protection market. Simultaneously, CropLife has warned that China’s shifting trade commitments could reshape global crop-protection supply chains, potentially raising costs for U.S. farmers. Labor shortages in agriculture have sharpened due to shifting immigration policy and enforcement. Enforcement-first labor strategies have contributed to supply chain disruptions in food and agriculture, affecting harvesting, processing, and rural labor markets. Soybean farmers, though less labor-dependent than specialty crop growers, still rely heavily on seasonal labor for trucking, grain handling, and logistics. Reduced export demand and increased costs ripple into rural communities, affecting equipment dealers, grain elevators, restaurants, and local tax bases.

Experts have emphasized that prolonged trade instability exposes deeper structural weaknesses in U.S. agriculture. Soybean production has increased in the past 20 years, driven by decades of policy and market consolidation that can magnify vulnerability to export shocks and may leave farmers with fewer alternatives as transportation and marketing systems adapt to the increased national production volumes. Many soy farmers use a corn-soybean rotation (soy helps add natural nitrogen to the corn crop, which has a high nitrogen absorption rate.) Advocacy groups like Farm Action have raised concerns about the potential for increased vulnerabilities, calling for diversification incentives, and antitrust enforcement. A prolonged federal shutdown affects U.S. agriculture more severely than many other sectors. The reopening of the government — whether after a budget lapse or protracted funding delay — has both immediate and long-term impacts on the soybean industry.

Restoration of USDA Market Reporting and Data Integrity

While “critical” government jobs were still operational, much of the work that is key to supporting USDA was stalled or paused. During shutdowns, USDA halts critical functions, including:

World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE) reports;

Export Sales Reporting (ESR);

Crop Progress reports; and

Loan and price support operations.

These data products guide global grain markets. Their absence increases price volatility and uncertainty. Upon reopening, USDA plays catch-up, but market participants often operate on stale or incomplete data — especially damaging in periods of already elevated trade uncertainty. Recent news coverage underscores how USDA data gaps have fueled confusion about China’s purchase commitments.

Resumption of Farm Service Agency (FSA) and Risk-Management Operations

The government shutdown impacted services that kept farmer-adjacent services running smoothly, which ultimately hampered soybean production, including:

Agriculture Risk Coverage (ARC)/Price Loss Coverage (PLC) and crop-insurance signups;

Loan processing;

Conservation program approvals; and

Disaster aid payments.

The shortfalls in funding to key programs ultimately delayed cash flow for farmers already absorbing export-related price shocks.

Restarting EPA Pesticide, Chemical, and Agricultural Approvals

While the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was not shutdown, key EPA functions were affected. Key EPA services that were impacted include:

Registration decisions (including herbicides, seed-treatment chemistries, and fumigants);

Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) rulemaking;

Pesticide label updates and enforcement guidance;

Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) complaint processing; and

Agricultural worker-protection activities.

EPA’s reopening is especially relevant; delays of even a few months can affect seed-purchasing plans and growers’ herbicide programs for the next planting season. EPA’s Agriculture News & Alerts page has repeatedly warned of program delays and backlog recovery each time a shutdown ends.

Resumption of Trade Diplomacy

While trade diplomacy continued during the government shutdown, many key foreign policy employees worked without support staff or reliable paychecks, and with far fewer resources. The reduced resources allotted to trade diplomacy affected:

Trade missions;

Negotiations with China, Mexico, and emerging soybean importers;

Embassy agricultural attaché reporting; and

Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS) market development programs.

This is directly relevant to U.S. efforts to secure new soybean buyers.In the days following reopening, diplomatic engagement typically spikes, as seen in recent U.S. appeals to China to stabilize agricultural relations ahead of high-level meetings.

Reopening of Immigration & Labor Functions

Shutdowns restrict U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) labor-certification processing and U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) immigration workflows, constraining farm labor supply. A reopening allows the release of backlogged H-2A visa certifications and resets enforcement priorities — critical for soybean-adjacent industries like grain transport, storage, and processing.

Policy Outlook for 2026

As the government reopens and agencies work through backlogs, several themes will shape soybean-sector stability:

Trade diplomacy action remains the central uncertainty;

Input cost inflation may persist as global crop-chemical markets adjust to China’s procurement signals;

Calls for diversification and domestic crush expansion are likely to grow louder;

Labor and immigration policy will increasingly be viewed as agricultural policy, not separate issues; and

Trade gyrations affect already low crop prices for U.S. producers, which further impacts farmers’ ability to purchase equipment and inputs such as pesticides.

The U.S. soybean sector sits at the nexus of trade, regulatory policy, and global supply chain dynamics. Tariffs and retaliatory measures continue to disrupt export flows, while rising input costs and structural vulnerabilities challenge financial resilience. The reopening of the federal government adds another layer of complexity — restoring critical operations but also revealing how deeply agricultural markets depend on the continuity of federal agencies. As the 2026 season approaches, policymakers, regulators, and industry stakeholders will need to navigate a landscape shaped by trade uncertainty, regulatory backlogs, and evolving global demand. The resilience of American soybean farmers will depend on the effectiveness of these policy responses and the stability of the institutions that support them.

Actualizing Therapy from Psychedelic Compounds Requires Acknowledging the Past Pioneers as well as Encouraging Cooperation from Current Market Players

In this era of industrialized capitalism, there are serious economic incentives to promote products in nascent industries. Intellectual property and the corresponding legal framework help achieve this promotion. Applying existing legal constructs to manufacturing products in burgeoning fields allows both the industry itself to grow and allows the players within those industries to profit from the growth that their innovation furthers within those industries. These players, however, are not necessarily only limited to the employees within the companies that make up the early competitive landscape. These players also include those pioneers that invented the foundational knowledge that has provided the original opportunities for these industries to exist. For example, biotechnology—including pharmaceuticals and biologics—has benefitted from the guidance that the Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”) and the United States Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) have promulgated over the years. While some of that has been codified statutorily, some only has been communicated outside of legislation through guidance and regulation.

Compounds that have been traditionally traced to psychedelic practice (e.g., LSD, ketamine, and psilocybin) have recently been chemically modified to negate their hallucinogenic properties. Researchers have done so by replacing functional groups off of the integral carbon rings that make up the chemical compounds that hypothetically alter the binding behavior of the receptors. Thus, there exists a unique opportunity to apply these compounds therapeutically. Furthermore, there also exists an unmet need for such medicine as there has been an increase in mental health issues globally which therapies using these compounds may be able to address. Thus, the incentive to expedite the possibility of providing therapy derived from these compounds has become increasingly important. The vehicle enabling such a possible medical breakthrough has yet to be established. We propose applying the already-existing patent system to this nascent industry, which would not only improve the financial situation of the players within the field (pioneers and market participants) as well as validate the science such that the therapeutic options that come from it are safe and trusted.

As basic research continues to unlock the potential of psychedelic compounds to alleviate treatment-resistant symptoms of psychological illnesses like major depressive disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder, there are certain problems that arise with the regulation of the fruits of this research as well as the research itself. As the number of patents issued covering therapeutic uses for psychedelic drugs has escalated rapidly, the industry itself faces urgency in regulating the growth.

Recently, Nature Medicine published online guidelines—Reporting of Setting in Psychedelic Clinical Trails (ReSPCT)—that outline a standardized protocol for psychedelic clinical trials that take into account the necessary safety considerations when administering psychedelics as well as the potential for their effective therapeutic potential. As of now, clinical trials for psychedelics do not provide the necessary framework to properly test the drugs for the FDA to readily rely upon the clinical endpoints that these protocols set. The ReSPCT framework consists of thirty variables, some of which include the environment in which the patients are administered the psychedelic drugs to be tested, how the drugs themselves are dosed and by whom, how the practitioners are supposed to intake the patients, and the actual therapeutic experience of the patients themselves. The guidelines acknowledge that there is fear within the industry that these drugs may in fact harm the patients, but these guidelines take such fear into consideration. While the ceiling for their therapy is high, there still needs to be motivation within the industry for a new regulatory framework as well as more attention toward basic research and clinical testing with the hopes that such attention to detail could ensure that the drugs work and that the patients would eventually not be harmed.

Such guidelines would help regulate the drug development of these dangerous compounds which would go a long way in ensuring the resulting therapies that such clinical research produces are both safe and effective. The FDA currently regulates the underlying clinical research required to approve pharmaceuticals and biologics, requiring market entrants to file a New Drug Application (“NDA”) for new pharmaceutical treatments and a Biologics License Application (“BLA”) for new biologic therapy. Within these submissions, drug manufacturers are required to include detailed information that must comply with the FDA’s strict quality standards before any medication can be administered to the public outside of those patients enrolled in the clinical trials detailed in these applications. These ReSPCT guidelines provide a framework that sets such a requirement in motion for treatment or therapy derived from psychedelic compounds.

Still, even with these guidelines, there remains a warranted recommendation to account for the pioneers that have been researching these compounds for hundreds of years privately. Porta Sophia is a nonprofit designed to address the difficulty in finding prior art that researchers and patent examiners face when designing and evaluating patent applications. Porta Sophia has collected thousands of prior art references from both common and uncommon spaces in an easily accessible database. Such a database’s benefit is at least four-fold: inventors can build on existing knowledge, investors can avoid losses on research that cannot be patented for lack of novelty, Indigenous practitioners are protected from external claims on their traditional knowledge, and potential patients have access to a broader scope of alternatives in the public domain. Thus, having a library that collects any sort of publicly-available information that chronicles the pioneering work of Indigenous traditional practice of psychedelic therapy would go a long way in preserving that knowledge for important laboratory-supported research that would inevitably legitimize the advancement of this knowledge as well as provide a verifiable collection of contemporaneous evidence to support any efforts to financially-reward the pioneers of the advancement of this field of study if such advancement were to transition into more scientifically-approved forums.

Preserving the Indigenous people’s ability to continue their traditional practices also has to be acknowledged. One potential regulation could be created a “ceremonial use” defense to patent infringement for psychedelic compounds and their methods of use. This defense would protect users from claims of infringement related to religious practices when either the plant or the underlying psychedelic compound had a prior religious use. This defense would be analogous to the existing doctrine of prior user rights, where a patent owner cannot sue for infringement based on continued use of a technology which was practiced in private before the patent was issued. The protections could be similar to the “safe harbor” provision of the Hatch-Waxman Act, which allows for the use of patented technology in the development of drugs. The current statutory framework is insufficient to protect ceremonial users because it only covers commercial uses of a technology, so further legislation is needed.

Finally, if the market transitions from nascent to profitable, such that the number of entrants would require the members to compete, industry players could agree to cooperate, similar to how early mRNA companies agreed to coexist during the pandemic. Specifically, the concept of patent pledges amongst these companies became common place. A patent pledge is when inventors commit to limiting the enforcement of their patents, typically spurring market forces to produce affordable copies of the invention for the public benefit. For instance, the Open Covid Pledge was designed to address the public health emergency of the COVID-19 pandemic by curbing enforcement of intellectual property related to treatments. Although the empirical analysis of whether patent pledges work to foster follow-on innovation is thin, there is data to support the idea that pledged patents stimulate start-up activities and provide the basis for further research. The downside of a purely voluntary patent pledge is that it can be difficult to enforce in court, frequently including stipulations and reservations of enforcement rights under certain conditions, adding substantial risk to follow-on research investments. Further legislation may be needed to reform the regulatory framework and provide a clear and predictable legal foundation for research using patented technologies in order to spur additional discovery.

The shifting political landscape has also affected the tenor of the debate around psychedelic medications, with HHS Secretary R.F.K. Jr. pushing an ambitious plan in June 2025 to have new psychedelic drugs rolled out to clinical settings within twelve months. Meanwhile, earlier in the month, Texas Governor Greg Abbot signed a law that invested $50 million into psychedelic clinical trials. Psychedelic research has bipartisan support, uniting politicians like Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-NY, with Rep. Dan Crenshaw, R-Texas, who both supported the House National Defense Authorization Act’s allowance of medical research on psychedelics. With both scientific and political aspects at an inflection point, psychedelic patent law is ripe for new regulatory legislation to provide structure, predictability, and support to all stakeholders.

It seems apparent at least to the authors of this article that therapy derived from psychedelic compounds providing treatment backed by the FDA and supported by the USPTO has entered or at least will very soon enter into this era of industrialized capitalism. Its foundations outside of the commonly-assumed origins of biotechnology—specifically, laboratory-backed basic research—should not be discounted, but acknowledged. Such acknowledgement not only extends to the science that has developed over centuries, but the pioneers who have fostered this development. The pioneers’ anti-establishment proclivities shouldn’t preclude us from rewarding these pioneers. Further, given psychedelic therapy’s entrance, we can be the arbiters of the industry’s success. Promoting legal systems and providing legislative structure that has helped grow other science-derived industries should help ensure that the resulting treatment is both safe and effective.

This article was co-authored by Jonathan Shelnutt (J.D. Candidate at Georgetown Law School).

In Search of: IEEPA Tariff Refunds

Highlights