FDA Issues FSVP-Related Warning Letters

FDA recently posted two warning letters issued to companies for failure to comply with the foreign supplier verification program (FSVP) requirements in Section 805 of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (21 USC 384a) and the implementing regulations in 21 CFR part 1, subpart L. FSVP is intended to verify that food imported into the U.S. is produced consistent with food safety standards that provide at least the same level of protection as the food safety standards that would apply to the food if it were produced in the U.S.

In one letter to Garcia Fresh Vegetables LLC, FDA indicated that the company had not developed an FSVP for any of the foods that it imports, including fresh produce. In another letter to Radhaswamy Inc. dba Raja Foods LLC, FDA stated that the company had failed to develop an FSVP for all but one of its products and had further failed to take any corrective actions following importation of a product that was added to an import alert due to pesticide adulteration.

Both warnings letters were issued after multiple inspections and following failures to respond to FDA 483a forms issued at the end of the inspections. FSVP violations continue to be a significant source of warning letters.

EPA Will Extend Deadline for Reporting Health and Safety Data for 16 Chemicals

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced on March 6, 2025, that it plans to issue a rule “soon” to extend the reporting deadline for a rule under Section 8(d) of the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) requiring manufacturers (including importers) of 16 chemicals to report data from unpublished health and safety studies to EPA. The rule applies to manufacturers in the North American Industrial Classification System (NAICS) codes for chemical manufacturing (NAICS code 325) and petroleum refineries (NAICS code 324110) that are currently manufacturing (including importing) a listed chemical substance (or will do so during the chemical’s reporting period), or that have manufactured (including imported) or proposed to manufacture (including import) a listed chemical substance within the last ten years. EPA states that the health and safety studies will help inform EPA’s prioritization, risk evaluation, and risk management of chemicals under TSCA. The current reporting deadline is March 13, 2025. EPA intends to extend the reporting deadline by 90 days to June 11, 2025, for vinyl chloride, and 180 days to September 9, 2025, for the other chemicals covered under the rule:

4,4-Methylene bis(2-chloraniline);

4-tert-octylphenol(4-(1,1,3,3-Tetramethylbutyl)-phenol);

Acetaldehyde;

Acrylonitrile;

Benzenamine;

Benzene;

Bisphenol A (BPA);

Ethylbenzene;

Naphthalene;

Styrene;

First Circuit Adopts But-For Causation Standard for Kickback-Premised False Claims Act Actions

On 18 February 2025, the First Circuit Court of Appeals issued its decision in United States v. Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., determining that “but-for” causation is the proper standard for False Claims Act (FCA) actions premised on kickback and referral schemes under the Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS). This issue has divided circuits in recent years, with the Third Circuit requiring merely some causal connection, and the Sixth Circuit and Eighth Circuit requiring the more defendant-friendly proof of but-for causation between an alleged kickback and a claim submitted to the government for payment.

This issue has major implications for healthcare providers, pharmaceutical manufacturers, and other entities operating in the healthcare environment. Both the government and qui tam relators have frequently brought FCA actions premised on alleged kickback schemes, and these actions pose significant potential liability. A higher but-for standard for proving causation represents a key tool for FCA defendants to defend against such actions. There is a good chance that the government petitions the US Supreme Court to review the First Circuit’s decision, and, given the growing split, there is certainly a possibility that this becomes the next issue in FCA jurisprudence that finds itself before the high court.

Background on AKS-Premised FCA Actions and the Growing Circuit Split

To establish falsity in an AKS-premised FCA action, a plaintiff has historically needed to show that the defendant (1) knowingly and willfully, (2) offered or paid remuneration, (3) to induce the purchase or ordering of products or items for which payment may be made under a federal healthcare program. In 2010, Congress added the following language to the AKS at 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b(g): “a claim that includes items or services resulting from a violation of [the AKS] constitutes a false or fraudulent claim for purposes of [the FCA].” (Emphasis added). Courts have generally agreed that the AKS, therefore, imposes an additional causation requirement for FCA claims premised on AKS violations. However, courts have been divided on how to define “resulting from” and the applicable standard for proving causation.

In 2018, the Third Circuit was faced with this issue and explicitly declined to adopt a but-for causation standard. Relying on the legislative history, the Third Circuit determined that a defendant must demonstrate “some connection” between a kickback and a subsequent reimbursement claim to prove causation.

Four years later, the Eighth Circuit declined to follow the Third Circuit and instead adopted a heightened but-for standard based on its interpretation of the statute. The court noted that the US Supreme Court had previously interpreted the nearly identical phrase “results from” in the Controlled Substances Act to require but-for causation. In April 2023, the Sixth Circuit joined the circuit split, siding with the Eighth Circuit and adopting a but-for causation standard.

Eyes Turn Toward the First Circuit

In mid-2023, two judges in the US District Court for the District of Massachusetts ruled on this causation issue as it related to two different co-pay arrangements, landing on opposite sides of the split. In the first decision, United States v. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc., the district court adopted the Third Circuit’s “some connection” standard. The court indicated it was following a prior First Circuit decision—Guilfoile v. Shields—though Guilfoile had only addressed the question of whether a plaintiff had adequately pled an FCA retaliation claim, as opposed to an FCA violation. In the second decision, Regeneron, the district court declined to follow Guilfoile (given Guilfoile dealt with the requirements for pleading an FCA retaliation claim); instead, the district court in Regeneron followed the Sixth Circuit and Eighth Circuit in applying a but-for standard. These dueling decisions set the stage for the First Circuit to weigh in on the circuit split.

First Circuit Adopts But-For Standard

On 18 February 2025, the First Circuit issued its opinion in Regeneron, affirming the district court’s decision and following the Sixth Circuit and Eighth Circuit in adopting a but-for standard. The court first determined that Guilfoile neither guided nor controlled the meaning of the phrase “resulting from” under the AKS. Turning to an interpretation of the statute, the First Circuit noted that “resulting from” will generally require but-for causation, but the court may deviate from that general rule if the statute provides “textual or contextual indications” for doing so. After a thorough analysis of the textual language and its legislative history, the First Circuit concluded that nothing warranted deviation from interpreting “resulting from” to require but-for causation. The court also rejected the government’s contention that requiring proof of but-for causation would be such a burden to FCA plaintiffs that the 2010 amendments to the AKS would have no practical effect.

Notably, the First Circuit made clear that its decision was limited to FCA actions premised on AKS violations under the 2010 amendments to the AKS. The court distinguished such actions from FCA actions premised on false certifications, where a plaintiff asserts that an FCA defendant has falsely represented its AKS compliance in certifications submitted to the government.

Takeaways

The growing confusion and disagreement among district and circuit courts over this issue, coupled with the issue’s import to FCA jurisprudence, creates the potential that this could be the next FCA issue decided by the US Supreme Court.

Until this split is resolved, FCA practitioners must pay close attention to the choice of venue for AKS-premised FCA actions.

But-for causation presents an important tool for FCA defendants in AKS-premised FCA actions. But-for causation may allow a defendant to argue that even if it had acted with an intent to induce referrals, no actual referrals resulted from the conduct, which would allow a defendant to avoid FCA liability altogether. Alternatively, but-for causation may allow a defendant to argue that FCA damages are lower than the total referrals made where the plaintiff is unable to prove all referrals “resulted from” the improper arrangement.

While this is a significant win for FCA defendants, its impact may be somewhat limited for FCA actions that are not premised on AKS violations. It also remains to be seen whether the government and relators will begin bringing FCA actions premised on alleged false certifications of compliance with the AKS (rather than solely relying on an alleged AKS violation itself).

The firm’s Federal, State, and Local False Claims Act practice group practitioners will continue to closely monitor developments on this issue, and we are able to assist entities operating in the healthcare environment that are dealing with AKS-premised FCA actions.

First Circuit Joins Other Circuits in Adopting Stricter Causation Standard in FCA Cases Based on Anti-Kickback Statute

On February 18, 2025, the First Circuit joined the Sixth and Eighth Circuits in adopting a “but for” causation standard in cases involving per se liability under the federal Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS) and the False Claims Act (FCA). In U.S. v. Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, the First Circuit held that for an AKS violation to automatically result in FCA liability, the government must show that the false claims would not have been submitted in the absence of the unlawful kickback scheme. The decision is the latest salvo in the battle over what it means for a false claim to “result from” a kickback, as discussed in our False Claims Act: 2024 Year in Review.

With the fight becoming increasingly one-sided — the Third Circuit remains the only circuit that has adopted a less stringent causation standard — the government may look at alternative theories to link the AKS and FCA.

Key Issues and the Parties’ Positions

As outlined in our previous posts on the issue, the legal dispute revolves around the interpretation of the 2010 amendment to the AKS, which states that claims “resulting from” a kickback constitute false or fraudulent claims under the FCA.

In this case, the government accused Regeneron of violating the AKS by indirectly covering Medicare copayments for its drug, Eylea, through donations to a third-party foundation. The government’s key argument relied on the Third Circuit’s Greenfield decision, the AKS’s statutory structure, and the 2010 amendment’s legislative history to argue that a stringent causation standard would defeat the amendment’s purpose. It urged the court to find that once a claim is tied to an AKS violation, it should automatically be considered false under the FCA — without the need to prove that the violation directly influenced the claim.

Regeneron, on the other hand, argued that an FCA violation only occurs if the kickback was the determining factor in the submission of the claim. Relying on the Eighth and Sixth Circuits’ decisions, prior Supreme Court precedent, and a textual reading of the amendment, Regeneron contended that the phrase “resulting from” could only mean actual causation and nothing less.

The Court’s Decision

The First Circuit sided with Regeneron. It found that, given the Supreme Court’s prior interpretation of “resulting from” phrase as requiring but-for causation, this should be the default assumption when a statute uses that language. While acknowledging that statutory context could, in some cases, suggest a different standard, the court concluded that the government failed to provide sufficient contextual justification for a departure from but-for causation.

The court rejected the government’s argument that, in the broader context of the AKS statutory scheme, it would be counterintuitive for Congress to impose a more stringent causation standard for civil AKS violations than for criminal AKS violations, which require no proof of causation. The court also dismissed the government’s legislative history argument — specifically, the claim that a but-for causation standard would undermine the impetus for the amendment.

Implication: False Certification Theories May Become More Prominent

The First Circuit was careful to distinguish between the per se liability at issue in this case and liability under a false certification theory. While the government must show but-for causation for an AKS violation to automatically give rise to FCA liability, the court said that the same is not true for false certification claims.

Any entity that submits claims for payment under federal healthcare programs certifies — either explicitly or implicitly — that it has complied with the AKS. The court noted that nothing in the 2010 amendment requires proof of but-for causation in a false certification case. The government may take this as a cue to pivot toward false certification claims as a means of linking the AKS and FCA, potentially leaving the 2010 amendment argument behind.

Final Thoughts

The First Circuit’s decision in U.S. v. Regeneron Pharmaceuticals further cements the dominance of the “but for” causation standard in linking AKS violations to FCA liability, making it increasingly difficult for the government to pursue claims under a per se liability theory. With three circuits now aligned on this interpretation and only the Third Circuit standing apart, the tide appears to be turning in favor of a stricter causation requirement.

However, as the court acknowledged, this ruling may not foreclose other avenues for FCA liability — particularly false certification claims, which at least this court has found do not require the same level of causal proof. Given this, the government may shift its focus toward alternative enforcement strategies to maintain the strength of its anti-kickback enforcement efforts. As the legal landscape continues to evolve, healthcare entities and compliance professionals should remain vigilant, as new litigation trends and regulatory responses may reshape the interplay between the AKS and FCA in the years to come.

Listen to this post

HHS Reverses Its Longstanding Policy and Limits Public Participation in Rulemaking

On March 3, 2025, the Secretary of Health and Human Services published a policy statement in the Federal Register that reverses a policy adopted over 50 years ago that was intended to expand public participation in the process of rulemaking at the Department of Health and Human Services (the “Department”). 90 Fed. Reg. 11029 (2025).

This action is at odds with the “radical transparency” that Secretary Kennedy had promised previously, and may affect many programs and financial relationships between individuals, organizations, and others that interact with Health and Human Services (“HHS”).

Regulatory agencies such as HHS and its components, including the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (“CMS”), the Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”), and the National Institutes of Health (“NIH”) must follow rulemaking procedures set out in the Administrative Procedure Act (“APA”) when they formulate and publish regulations that are intended to implement a statute and have the force of law. Those procedures include offering the public an opportunity to be notified of proposed regulations and to submit comments to the agency. The APA also contains several exceptions to the notice and comment requirement, including one for matters relating to “public property, loans, grants, benefits, or contracts.” Nevertheless, HHS and several other federal departments adopted policies that voluntarily waived these exceptions.

In 1971, then-Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare Elliot Richardson issued a policy statement announcing that the Department would voluntarily follow notice and comment procedures for regulations relating to public property, loans, grants, benefits, or contracts (the “Richardson Waiver”). That notice explained that the waiver would allow for greater participation by the public in the rulemaking process, and that the additional burden on the Department was outweighed by the public benefit. The policy also instructed that although the APA allows for rulemaking procedures to be waived when good cause exists, that exception should be used “sparingly.”

HHS’s New Policy Limiting Rulemaking and Potential Safeguards

The new HHS policy statement sweeps away the 1971 policy. Its impact may vary depending on the issue and component of HHS. For example, for research funded by the NIH or other projects funded by agencies within HHS, the new policy could allow a granting or contracting agency to amend financial terms without public participation. This exact issue is currently in the spotlight as courts actively evaluate the legality of the NIH’s recent Supplemental Guidance to the 2024 NIH Grants Policy Statement: Indirect Cost Rates (NOT-OD-25-068))(“Supplemental Guidance”), issued by the Office of the Director of the National Institutes of Health on February 7, 2025, which attempted to impose an across-the-board 15% cap on Indirect Cost (“IDC’) rates for all new grants as well as for existing grants awarded to Institutions of Higher Education. The District Court of Massachusetts has imposed a nationwide preliminary injunction (“PI”) prohibiting the Secretary and NIH from taking any steps to implement or enforce the Supplemental Guidance. Commonwealth of Massachusetts, et al. v. National Institutes of Health, et al., No. 25-CV-10338 (D. Mass. Mar. 5, 2025). The court concluded that the plaintiffs would be irreparably harmed by the Supplemental Guidance and agreed that the Supplemental Guidance was a legislative rule that failed to comply with the notice and comment requirements of the APA. It relied in part on the argument that under the Richardson Waiver, the Secretary could not change the IDC rate unilaterally. The timing of the Department’s policy reversing the Richardson Waiver might be viewed as directly responsive to this disputed point in the ongoing litigation.

In other areas, the policy statement may have little or no impact if there is a separate statutory requirement for rulemaking. In the Medicare statute, for example, Congress mandated in Section 1871(a)(2) of the Social Security Act that HHS must engage in notice and comment rulemaking for any “substantive legal standard governing the scope of benefits, the payment for services, or the eligibility of individuals, entities, or organizations to furnish or receive services or benefits . . . .” Should Congress decide to limit the scope of the new HHS policy, this statute could be a template for legislation.

The impact of the new policy on the Medicaid program is less clear. While there is no similar statutory requirement for rulemaking under the Medicaid program as there is for Medicare, the federal government also has more limited control over the direction of each individual State’s Medicaid program offering. However, there are areas where HHS has sought public comment on changes to state Medicaid program requirements in the past, such as changes proposed by States through Medicaid program waivers that the federal government has to approve. This new policy may be signaling that HHS will choose not to seek comments on those proposed changes in the future.

Returning to the IDC rate litigation, there arguably exists both statutory and regulatory grounding for applying grantees’ existing negotiated indirect cost rates, documented in the negotiated indirect cost rate agreement (“NICRA”) entered into between the government and grantee institutions. First, a provision in the annual appropriations act since 2018 has limited Congress’ ability to impose any type of across-the-board cap. See Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2024, P.L. 118-47, Title II, § 224. This was adopted in response to the first Trump administration’s attempt to impose an across-the-board cap of 10% in 2017. Second, in the HHS regulations applicable to IDC rates, there is an explicit requirement that the negotiated rates must be “accepted by all Federal awarding agencies.” 45 C.F.R. § 75.414(c)(1). This regulatory exception, and alleged noncompliance with the APA’s rulemaking requirement, is at the core of the ongoing IDC rate litigation. As such, there are arguably continued bases for the objection to the NIH Supplemental Guidance notwithstanding the recent reversal of the Richardson Waiver.

Does HHS’s New Policy Signal a Wider Use of the “Good Cause” Exception?

Another part of the new HHS policy to watch carefully involves the exception in the APA that allows agencies to dispense with notice and comment rulemaking when there is good cause that a notice and comment period is impractical or contrary to the public interest. The new HHS policy states that agencies may rely on the good cause exception “in appropriate circumstances” rather than “sparingly” but provides no further clarification.

Courts have interpreted this exception narrowly; for example, they have upheld good cause exceptions when agencies have responded to epidemics and natural disasters, but have rejected exceptions claimed by agencies due to statutory deadlines, economic concerns, or a need to implement a political goal rapidly. In addition, a 2012 report published by the General Accountability Office criticized the frequent use of the good cause exception to avoid public comments on rules. Therefore, it remains to be seen how and when HHS relies on this exception, and whether the reasons offered justify the exception or would stand up to judicial review.

This Week in 340B: February 25 – March 3, 2025

Find this week’s updates on 340B litigation to help you stay in the know on how 340B cases are developing across the country. Each week we comb through the dockets of more than 50 340B cases to provide you with a quick summary of relevant updates from the prior week in this industry-shaping body of litigation.

Issues at Stake: Antitrust; Contract Pharmacy; HRSA Audit Process; Rebate Model

In an antitrust class action case, the court granted the defendant’s motion to dismiss.

In an appealed case challenging a proposed state law governing contract pharmacy arrangements, a group of amici filed an amicus brief in support of appellees.

In an appealed case challenging a proposed state law governing contract pharmacy arrangements, defendants-appellants filed an opening brief.

In a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) case, the plaintiff filed a reply in support of its motion to strike the government’s motion for summary judgment.

In one Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) audit process case, the plaintiff filed a supplemental brief in support of the plaintiff’s motion for preliminary injunction.

A group of 340B covered entities filed a complaint against a group of commercial payors, alleging that the payors were in breach of their contracts by failing to pay the proper amounts for 340B-acquired drugs.

In three cases challenging a proposed state law governing contract pharmacy arrangements in Missouri, the court denied in part and granted in part two separate motions to dismiss and denied plaintiff’s motion for a preliminary injunction in a third case.

In two cases against HRSA alleging that HRSA unlawfully refused to approve drug manufacturers’ proposed rebate models:

In one such case, a group of amici filed an amicus brief in support of defendants.

In one such case, a group of amici moved for leave to file an amicus brief in support of plaintiffs’ motion for summary judgment.

Additional Authors: Kelsey Reinhardt and Nadine Tejadilla

Federal Circuit Refuses to Rehear Case Involving Orange Book Listing of Device Patents

Late last year we reported on the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit decision holding that certain device patents should not have been listed in the FDA’s Orange Book since the claims of the patents in question did not recite the active drug substance.

Following that decision, the brand company patent holder, Teva, filed a petition to request the Federal Circuit to rehear the case in front of all judges in the Circuit. Teva’s position was supported by a number of brand pharmaceutical companies, as well as the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America.

On Monday, March 3, 2025, the Federal Circuit entered an Order denying Teva’s rehearing request. Teva may still attempt to appeal the December 2024 Federal Circuit decision to the United States Supreme Court, but there is no guarantee that the Supreme Court will agree to hear the case.

If left undisturbed by the Supreme Court or further legislative or regulatory actions, the Federal Circuit decision begins to provide some clarity regarding whether device patents can be listed in the Orange Book when they do not recite the active ingredient. Either way, further litigation involving Orange Book patent listings can be expected. It will be important for both brand and generic companies to carefully review the specific language of all patent claims that may be or are currently in the Orange Book for approved drugs where there are device components associated with the drug.

How Alcohol Exporters Can Use FDII and IC-DISC to Maximize Tax Savings

For US alcohol exporters – whether crafting bourbon, brewing craft beer, or bottling fine wines – selling to international markets is a significant opportunity for growth. Two US federal income tax regimes, the foreign-derived intangible income (FDII) deduction and the interest charge-domestic international sales corporation (IC-DISC), offer valuable ways to reduce tax liability and boost profits. Each has unique benefits and trade-offs, making them suited to different business needs. This blog post compares FDII and IC-DISC, helping alcohol exporters decide which tool – or combination – best fits their global ambitions.

Note that all discussions of tax rates are limited to US federal income tax. Additional state and local taxes and excise taxes may also apply.

FDII for Export Income

Introduced under the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), FDII incentivizes US C corporations to earn income from foreign sales while keeping operations stateside by providing a reduced effective tax rate on eligible export income derived from US-based corporations. It targets “intangible” income – profits exceeding a routine return on tangible assets – and applies a deduction directly on the exporter’s tax return.

How FDII Works

Eligible income comes from selling alcohol (e.g., whiskey or wine) to foreign buyers for use outside the United States.

The FDII deduction is 37.5% of qualifying income (dropping to 21.875% after 2025), reducing the effective corporate tax rate from 21% to 13.125% on that portion of income.

No separate entity is required. Claims are made on the existing C corporation’s Form 1120.

Example: A winery exporting $2 million in Pinot noir with $400,000 in net profit might qualify $300,000 as FDII. A 37.5% deduction ($112,500) lowers the tax from $63,000 to $39,375, saving $23,625.

IC-DISC: A Classic Deferral and Rate Reduction Tool

The IC-DISC, a legacy export incentive from the 1970s, operates as a separate “paper corporation” that earns commissions on export sales. It is available to any US business structure (e.g., C corporations, S corporations, and LLCs) and shifts income to shareholders at a lower tax rate or defers it entirely.

How IC-DISC Works

The exporter forms an IC-DISC and pays the entity a commission (up to 4% of export gross receipts or 50% of net export income).

The commission is deductible for the operating company, reducing its taxable income.

The IC-DISC pays no federal tax; instead, its income is distributed to shareholders as qualified dividends (taxed at 20% capital gains rate) or retained for deferral.

Example: A distillery owned by a closely held pass-through entity with $2 million in export sales and $400,000 in net profit pays a $200,000 commission to its IC-DISC. The operating company saves $74,000 in income tax (37%), while shareholders pay $47,600 in capital gains tax (20% plus 3.8% net investment income tax) on the dividend, netting a $27,600 savings.

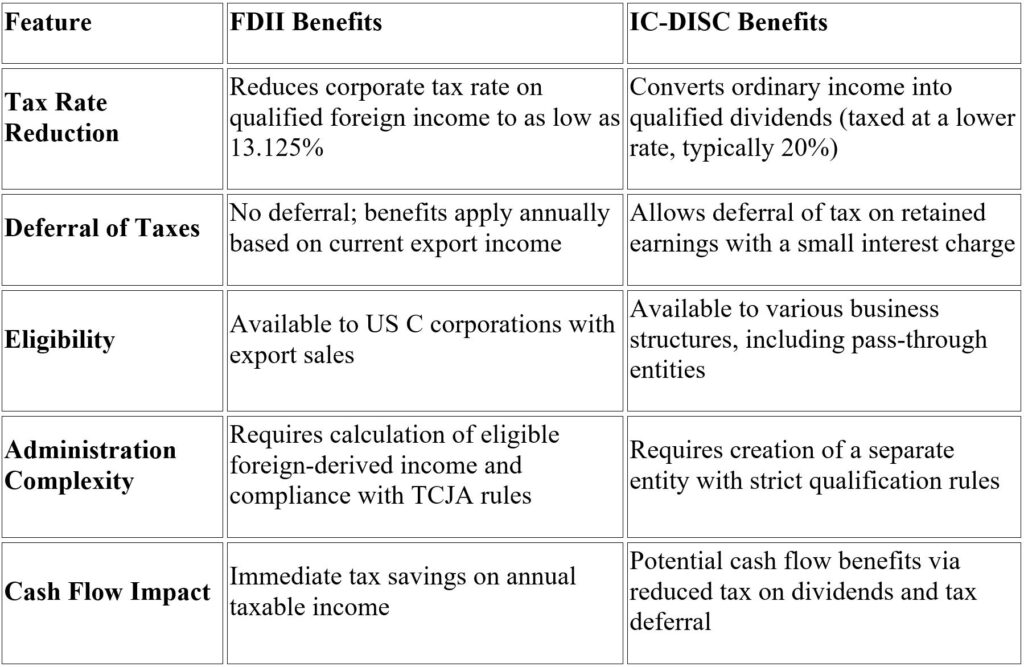

Comparing Tax Benefits: FDII vs. IC-DISC

Combining FDII and IC-DISC?

For alcohol manufacturers and distributors, using both FDII and IC-DISC is possible. FDII reduces the corporate tax rate on export income, while an IC-DISC could shift additional income to shareholders at the capital gains rate or defer it.

Conclusion

FDII and IC-DISC are potent tools for alcohol exporters, each with distinct strengths. FDII delivers a lower tax rate with minimal effort, ideal for C corporations riding the wave of global demand for American products. IC-DISC offers flexibility, deferral, and broader eligibility, suiting a wider range of businesses with an eye on cash flow. As the craft beer, spirits, and wine industries expand abroad, choosing the right regime – or blending them – can uncork significant savings. Consult a tax professional to tailor the choice to your operation.

New State Legislative Efforts to Regulate Color Additives in Food

The introduction of state legislation purporting to regulate food colors and dyes, which saw more than a dozen states introducing bills in 2024, continues to move forward. Recently, California issued an executive order to recommend actions to reduce foods with synthetic food dyes, and Utah recently introduced H.B. 402 seeking to prohibit foods containing various synthetic dyes. Two new additional legislative efforts have emerged from Florida and Virginia.

Florida’s HB641

On January 15, 2025, Florida representatives introduced a new bill, HB641, which seeks to increase transparency for consumers regarding the presence of synthetic dyes in food products. If passed, this bill would require food manufacturers to include a warning label on products containing synthetic dyes.

Virginia’s SB1289:

On February 10, 2025, both chambers of Virginia’s legislature passed SB1289, a bill that will eliminate certain color additives, including Red 40, Yellow 5, and Blue 1, from the food served in the state’s elementary and secondary schools.

We expect to see continued activity at the state level, and following the FDA’s recent action on Red No. 3, advocacy at the federal level may increase.

Cultivated Meat: Legislative Challenges from Georgia and South Dakota

As we’ve previously blogged, the regulatory landscape for cultivated meat is rapidly evolving with states like Nebraska, Florida, and Alabama taking significant steps to restrict or ban these products. The recent legislative actions in Georgia and South Dakota are the latest in various states’ efforts to regulate or restrict these products more stringently.

Georgia General Assembly- HB 163:

On February 27, 2025, the Georgia House of Representatives passed House Bill 163, which, if passed by the Senate, would require restaurants and other food vendors to disclose whether their menu items contain cultivated meat, plant-based meat alternatives, or both. The bill defines “cell-cultured meat” as any food product artificially grown from cell cultures of animal muscle or organ tissues, designed to mimic conventional meat products.

Similarly, “plant-based meat alternatives” are defined as products derived from plants that share sensory characteristics with traditional meat. The bill has passed the Georgia House of Representatives and is currently under review by the Senate Agriculture and Consumer Affairs Committee.

South Dakota- HB 1118

Meanwhile, South Dakota has taken a different stance with House Bill 1118, which has already passed into law. This legislation prohibits the use of state funds for the research, production, promotion, sale, or distribution of cell-cultured protein.

The bill defines “cell-cultured protein” as any product made wholly or in part from cell cultures or the DNA of a host animal, grown outside a live animal.

These bills represent the latest developments of state-level challenges being presented to the cultivated meat industry.

Raw Milk: State Legislative Updates and Challenges

Several states have recently introduced or passed legislation related to raw milk, reflecting a growing interest in unpasteurized milk despite the fact that raw milk can carry harmful bacteria such as Salmonella, E.coli, and Listeria, posing serious health risks. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) strongly advise against consuming raw milk due to these dangers and have implemented regulations to limit its sale.

Despite the long-standing position at both agencies, the new Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Robert F. Kennedy Jr., has been a vocal advocate for raw milk promoting its benefits and criticizing regulatory restrictions. His support has brought renewed attention to the raw milk movement, influencing legislative efforts.

Arkansas Bill HB 1048: This bill would allow the sale of raw goat milk, sheep milk, and whole milk directly to consumers at the farm, at farmer’s markets, or via delivery by the farm.

Utah Bill HB414: This bill has passed the House and is now before the Senate. This bill establishes enforcement steps for raw milk suspected in foodborne illness outbreaks, aiming to protect consumers.

Other states’ Legislation: States including Iowa, Minnesota, West Virginia, Maryland, Rhode Island, Oklahoma, New York, Missouri, and Hawaii have introduced various raw milk-related bills with efforts ranging from expanding sales to implementing stricter safety regulations.

Meat Industry Pushes Back on Cultivated Meat Bans

While several states are taking legislative action to restrict or ban the sale of cultivated meat, with legislators arguing that the bans would protect the meat industry, there is a different message coming from many groups in the industry itself. Critics of the bans argue that they would “restrict free trade and threaten food safety benefits.”

Nebraska, a state that ranks among the top 10 producers of beef and pork, is among many of the states that has proposed a cultivated meat ban, and the state’s governor issued an executive order in August 2024 barring state agencies from buying cultivated meat. However, ranchers and meat industry groups are pushing back on the ban, saying that “it’s up to the consumer to make the decision about what they buy and eat.” Industry groups say that they are “not worried about competition” from cultivated meat but prefer a different approach that would require the products to be clearly labeled as lab-grown.

The North American Meat Institute has similarly opposed cultivated meat bans, writing a letter in opposition to the Florida ban in February 2024. In its letter, the organization says that the bills would be preempted by the Federal Meat Inspection Act, which regulates the processing and distribution of meat products in interstate commerce. Further, the Meat Institute argued that the bans are “bad public policy that would restrict consumer choice and stifle innovation” and that USDA oversight of cell cultivated meat products places the products on a level playing field in terms of food safety and labeling requirements.

In addition, legislators in Wyoming and South Dakota have voted against cultivated meat bans in their states, citing free trade manipulation and urging instead for more packaging and labeling regulations to support informed decisions.