Case Closed: Commission Sanctions Ruling Isn’t an Import Decision

The US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit dismissed an appeal for lack of jurisdiction, finding that a denial of sanctions at the International Trade Commission was not a “final determination” under trade law because it did not affect the exclusion of imported goods. Realtek Semiconductor Corp. v. ITC and Future Link Systems, LLC, Case No. 23-1187 (Fed. Cir. June 18, 2025) (Reyna, Bryson, Stoll, JJ.)

In 2019, Future Link entered into a license agreement with MediaTek, Inc. (not a party to the present litigation), which included a provision for a lump-sum payment if Future Link filed a lawsuit against Realtek. Future Link subsequently initiated a patent infringement complaint against Realtek before the Commission. During the proceedings, Future Link settled with a third party and determined that the settlement resolved the underlying dispute, prompting it to notify Realtek and ultimately withdraw its complaint. Realtek moved for sanctions, citing the MediaTek agreement as improper, but the administrative law judge (ALJ), while expressing concern about the agreement’s lawfulness, found no evidence it influenced the complaint and denied sanctions. The Commission terminated the investigation after no petition for review of the ALJ’s termination order was filed. Realtek then petitioned the Commission to review the denial of sanctions, but the Commission declined, closing the sanctions proceeding. Realtek appealed to the Federal Circuit, not challenging the investigation’s termination but seeking an order requiring Future Link to pay a fine based on the alleged impropriety of its agreement with MediaTek.

Realtek argued that the Commission and the ALJ violated the Administrative Procedure Act (APA). In response, the Commission and Future Link not only defended the denial on the merits but also challenged the Federal Circuit’s jurisdiction and Realtek’s standing to appeal. The Court agreed that it lacked jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 1295(a)(6), which only authorizes review of final determinations under specific subsections of Section 337 of the Tariff Act of 1930 (19 U.S.C. § 1337). Because the Commission’s denial of sanctions under subsection (h) does not constitute a “final determination” under § 1337(c), the Court declined to address standing or the merits of the sanctions issue.

The Federal Circuit emphasized that a “final determination” within the meaning of § 1295(a)(6) refers to decisions affecting the exclusion of imported articles, such as those made under subsections (d), (e), (f), or (g) of § 1337. Realtek argued that the Commission’s denial of its sanctions request qualified as a final merits decision, but the Court disagreed, citing long-standing precedent, including its 1986 decision in Viscofan, S.A. v. ITC, that limits appellate jurisdiction to exclusion-related rulings. Because the sanctions decision had no bearing on whether products were excluded from importation, the Court held that it lacked the authority to review and dismissed the appeal.

Confidentiality Agreements Applied to Nonparty Recipients

In Dale v. T-Mobile US, Inc. – a putative antitrust class action litigation – Magistrate Judge Jeffrey Cole resolved whether and to what extent confidentiality agreements between parties apply to productions nonparty recipients of subpoenas made.

Background

In this litigation, the parties entered a confidentiality order governing discovery in the case. After the parties issued subpoenas to numerous non-parties, a dispute with the non-parties arose regarding certain portions of the confidentiality order. Although the parties and the non-party subpoena recipients “nearly reached agreement [during meet and confers] for amending the Confidentiality Order,” they could not agree on certain topics, including whether defendant’s in-house counsel would be permitted to review highly confidential information from the non-parties. A motion to amend the confidentiality order was brought to the court.

Although Judge Cole ultimately denied the motion, he provided the parties and non-parties with guideposts and encouraged all to work cooperatively toward a mutually acceptable resolution. Magistrate Judge Cole initially noted that non-parties have “vastly different expectations regarding the confidentiality of their information” and explained that “parties to a lawsuit must accept the invasive nature of discovery, non-parties are just that, not parties …, and they generally do not have anywhere near the same skin in the game.” Therefore, “a non-party is entitled to greater protection in the discovery process than parties….”

Judge Cole then turned to the merits of the parties’ arguments. In rejecting defendant’s argument that the non-parties should be bound by the confidentiality order because the court was “well-aware of the nonparty discovery that Plaintiffs’ claims would entail,” the judge cited to the plain language of the confidentiality order, noting that by its terms the order applies only to “any named Party to this action … and to Non-Parties who agree to be bound by this Order.” Magistrate Judge Cole then analyzed the three factors a court must consider when the modification of a confidentiality agreement is sought (citing Heraeus Kulzer, GmbH v. Biomet, Inc.). He found the first factor, the nature of the order, favored modification “because the non-parties did not agree” to the confidentiality order. He concluded that the second factor, the foreseeability that modification would become necessary, also favored the non-parties because the parties’ agreement “left open the very real possibility that non-parties — competitors with one of the parties — would disagree with it.” Finally, he found the third factor, the parties’ reliance on the order, “is really neither here nor there” because they knew “non-parties they planned on subpoenaing would understandably balk.”

Regarding the substance of the non-parties’ objections to the confidentiality order, Magistrate Judge Cole noted that “[t]he non-parties have some very real concerns about in-house counsel for a competitor poring over their documents” and that “it is no small matter for in-house counsel to compartmentalize information learned in discovery.”

Magistrate Judge Cole urged the parties and non-parties to “take a critical look at their current positions and make another attempt to come up with something workable” and to “think creatively with an eye toward what is truly and not merely academically meaningful.” He also suggested that the parties and non-parties “put together some sort of mutually acceptable agreement rather than have something perhaps imposed on them down the road.” Ultimately, Magistrate Judge Cole denied the motion to amend the confidentiality order and ordered the parties to meet and confer “with the forgoing considerations and weaknesses in positions in mind.”

Conclusion

This decision provides a few useful reminders. First, disputes that can be resolved without imposing upon the court should seek to be resolved amicably. It also serves as a reminder that parties will be bound by the plain terms of an agreement – especially one the court orders. Finally, protections afforded to non-parties in a litigation may be greater given the different expectations of non-parties who have “no skin” in the litigation. Thought should be given to this when drafting agreements that might impact a non-party.

An Oft-Overlooked Requirement in the N.Y. Commercial Division Rules: The Rule 11-e(d) Statement of Completion

Effective April 1, 2015, the Commercial Division of the New York State Supreme Court promulgated a series of reforms to the Rules of Practice for the Commercial Division, including the addition of new Rule 11-e, which provides specific requirements for responding and objecting to document requests.

In particular, Rule 11-e(a)-(b) requires parties to provide particularized responses and specify in detail whether documents are being withheld in response to all or part of the requests, and Rule 11-e(c) requires a date for the completion of document production prior to depositions. These are markedly different than those required by the Uniform Civil Rules that govern non-Commercial New York State Supreme Courts and County Courts, and have been the subject of much discussion by courts and practitioners in the ensuing years. However, one significant requirement of Rule 11-e that is often overlooked concerns Rule 11-e(d).

In particular, Rule 11-e(d) provides as follows:

(d) [b]y agreement of the parties to a date no later than one (1) month prior to the close of fact discovery, or at such time set by the Court, the responding party shall state, for each individual request: (i) whether the production of documents in its possession, custody or control and that are responsive to the individual request, as propounded or modified, is complete; or (ii) that there are no documents in its possession, custody or control that are responsive to the individual request as propounded or modified.

In other words, in addition to responding and objecting to document requests at the outset with specificity as required by Rule 11-e(a)-(b), one month prior to the close of fact discovery or another date set by a court, parties are further required to issue a statement that specifically denotes for each request whether document production is complete as requested or modified, or that they are not in possession of responsive documents. Such a formal obligation at the conclusion of discovery to specify whether production is complete for each individual request is not found in the Uniform Civil Rules or the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, and appears to be entirely unique.

Despite this, Rule 11-e(d) seems to have largely gone unaddressed in the last decade with most courts and practitioners focusing instead on the other significant requirements of Rule 11-e. Even so, as recently as 2023, in Men of Steel Enterprises, LLC v. Bespoke Harlem W., LLC, 2023 N.Y. Slip Op. 30404[U] (Sup. Ct. N.Y. Co. 2023), the Honorable Joel M. Cohen ordered plaintiffs to submit amended responses to comply with the requirements of Rule 11-e(d) and did so despite the fact that plaintiffs had already represented in their opposition that they had produced all responsive documents and did not have additional documents in their possession, custody, and control—demonstrating that the Rule is alive and well and may be enforced to the full extent, even if merely as a formality. While it remains unclear how focused courts will be on the requirements of Rule 11-e(d) statements going forward, including their form and use, those practicing in the Commercial Division should be prepared to comply with its requirements.

After Oral Argument, Supreme Court Dismisses Labcorp Appeal of Class Certification Based On Article III Standing and Circuit Split Persists

On April 29, 2025, the Supreme Court heard oral argument in Labcorp v. Davis, in which it considered the question of whether Article III standing must be determined for all members of the class, including uninjured members, at the outset of class certification. The issue presented is one that has deeply divided the federal courts of appeals after it was left open by the Court’s prior rulings in TransUnion LLC v. Ramirez and Spokeo, Inc. v. Robins. On June 5, 2025, the Supreme Court dismissed the case as improvidently granted, leaving the question unresolved.

Backdrop: Labcorp Case Before the Ninth Circuit

In 2020, a class actional lawsuit was filed against Labcorp alleging that its express self-check-in kiosks violated federal and California disability laws because they were not accessible to blind individuals. The District Court certified two classes of legally blind Labcorp patients who were unable to access the kiosks: a nationwide class for purposes of injunctive relief under the ADA and a California class for purposes of monetary damages under the California statute.

On appeal, the Ninth Circuit affirmed the class certifications. Labcorp petitioned for review, arguing that only those who actually used the kiosks had Article III standing to sue and all uninjured members included in the class could not sustain their claims because they lacked an Article III injury.

The Supreme Court granted certiorari. The question presented for the Court’s consideration was as follows:

May a federal court certify a class action pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23(b)(3) when some members of the proposed class lack any Article III injury?

Labcorp’s Argument: Article III Standing Necessary for Class Certification

Petitioner Labcorp’s argument hinged on the predominance requirement of Rule 23(b)(3). Citing to In re Rail Freight Fuel Surcharge Antitrust Litigation and In re Asacol Antitrust Litigation from the D.C. Circuit and First Circuit, respectively, counsel for Labcorp noted that, when a class is defined to include plaintiffs without Article III standing, the Article III issue predominates and swamps any common issues.

Labcorp explained that, if a class is defined on the front end such that both injured and uninjured individuals are encompassed by the definition of the class, thousands of mini-trials would have to be conducted to separate them, which it argued would become more important than any other common issues.

The justices questioned Labcorp as to why uninjured members would require standing given that, ordinarily, only one person must satisfy the standing criteria in order to invoke the jurisdiction of the Court.

Moreover, the justices highlighted that, specifically in the class context, absent class member claims are added to the case when it is certified, but they are not added as new parties. Based on this distinction, the justices further questioned why it would be necessary to prove whether individuals were injured or uninjured at the outset.

The justices’ final line of questioning pertained to when the appropriate time would be to determine Article III standing, with one of the justices suggesting that the determination of Article III standing is only pertinent when apportioning damages.

The rationale for this was that courts do not do anything with respect to uninjured members’ claims until the damages stage. Thus, because uninjured class members’ claims are “just riding along [and] not affecting the litigation in any way,” the justices highlighted that this cast doubt on the necessity of a showing of Article III standing at the outset.

Respondent’s Argument: Article III Standing Not a Requirement for Absent Members

Counsel for Respondent Davis began his argument highlighting that centuries of precedent dictate that only the representative of a class, who is actually before the court as a named party, must prove Article III standing at the outset of class certification and not the absent class members.

Further, Davis’ counsel argued that the understanding has always been that absent class members are not parties over whom the court exercises jurisdiction unless and until the court is doing one of two things: exercising its remedial power with respect to an absentee or deciding a question that it wouldn’t otherwise have to decide, such as an individual question.

The justices’ main line of questioning revolved around how uninjured members would be eventually left out of the damages calculation. Counsel noted that there would have to be an administratively feasible mechanism outlined at the outset to weed out the uninjured members for damages purposes.

Counsel for Davis ended by arguing that Labcorp’s proposed alternative could actually have disastrous consequences for other defendants. As is, defendants can “rest easy knowing that they’ve prevailed in a class action and someone isn’t going to run into state court and bring the exact same claim and say, a-ha, we didn’t have Article III standing in that first case.” This, counsel argued, would disturb the finality of class-wide judgments.

Supreme Court’s Dismissal of the Case and Kavanaugh’s Dissent

On June 5, 2025, the Supreme Court dismissed the case, noting that it had been improvidently granted. Justice Kavanaugh, however, dissented, and the concerns highlighted in his dissent were foreshadowed by his questioning concerning real-world consequences during argument.

Justice Kavanaugh stated that he “would hold that a federal court may not certify a damages class that includes both injured and uninjured members.” His rationale was that, when there is a damages class that includes both injured and uninjured members, the case could not by definition meet the Rule 23 requirement that common questions predominate.

Turning attention to real-world consequences, Justice Kavanaugh noted that classes that are overinflated with uninjured members threaten massive liability for businesses that are targeted with class actions. This, he said, can coerce businesses into unjustifiably costly settlements, which could have severe and widespread consequences. When forced into unjustifiably costly settlements, businesses would then raise the costs of doing business and would be forced to pass on the costs to consumers in the form of higher prices, to retirement account holders in the form of lower returns, and to workers in the form of lower salaries and lesser benefits.

Future of Article III Standing and Class Certification with a Surviving Circuit-Court Split

Currently, there is a three-way split amongst circuits regarding the question of Article III standing and class certification.

The D.C. Circuit and First Circuit permit certification of a class only if the number of uninjured members is de minimis. The Ninth Circuit permits certification even if the class includes more than a de minimis number of uninjured class members. The Eighth and Second Circuits have taken the strictest approach, rejecting certification if any members are uninjured.

Because the Supreme Court still has not ruled on the issue, defendants should continue to scrutinize potential standing deficiencies for both class representatives and absent class members as well. However, there may yet be a resolution, as the issue has been raised again in State Farm Mut. Auto. Ins. Co. v. Jama.

In its petition for certiorari, State Farm poses the question of whether a Rule 23(b)(3) damages class can be certified when some members of the proposed class lack any Article III injury. Whether the Supreme Court will grant certiorari is unclear, but if it does, there will be a renewed opportunity for the Court to answer the question and resolve the longstanding circuit split on the issue.

Texas Governor Signs HB 40, Expanding Jurisdiction of the Texas Business Court

On the final day of the 89th Legislative Session, the Texas Legislature passed House Bill 40 (HB 40) to expand the jurisdictional and operational framework of the Texas Business Court.1 The Bill has since been signed by Governor Abbott and becomes effective on September 1, 2025. The new law builds on Texas’s 2023 initiative to establish a specialized venue for complex business litigation and makes the forum more accessible to corporate litigants. The most significant changes include amendments to reduce the monetary threshold for invoking the Business Court’s jurisdiction and to expand the category of case types that may be heard.

The Bill’s amendments, coupled with broader national conversations around litigation costs and court specialization, support the Business Court playing an increasingly important role in the national corporate governance and commercial litigation landscape. The new statutory changes also make now the time for Texas businesses and in-house counsel to evaluate whether their governing documents and contracts are up-to-date to take full advantage of Texas’s new laws.

Reduced Monetary Threshold

HB 40 lowers the Business Court’s amount-in-controversy requirement from $10 million to $5 million — and allows that threshold to be met by aggregating “the total amount of all joined parties” claims — for certain case types. These include:

cases arising out of a “qualified transaction” (defined as any single transaction or a “series of related transactions” with consideration valued at or above $5 million);

actions arising out of a “business, commercial, or investment contract or transaction,” other than an insurance contract, in which the parties agree to Business Court jurisdiction;

claims involving alleged violations of the Texas Finance Code or Business & Commerce Code by an organization, its officers or other governing persons; and

certain matters relating to intellectual property rights or trade secrets disputes.

Under the initial version of the Texas Business Court Act that passed in 2023, the lower $5 million threshold applied only to fundamental internal governance and securities matters — such as derivative actions, internal affairs disputes, securities claims against an organization or related persons, fiduciary duty claims against controlling persons and managerial officials and the like. The Bill’s promulgation of a lower threshold for other claim types within the Court’s jurisdiction should ultimately make the Business Court more accessible to a broader array of commercial parties and increase the volume of cases.

Additional Claim Categories Within Business Court Jurisdiction

In a significant addition, HB 40 adds intellectual property and trade secrets claims to the statute’s jurisdictional coverage. While the 2023 Act did not authorize the Business Court to hear intellectual property matters, HB 40 now expressly permits the Court to hear trade secrets cases and other “action[s] arising out of or relating to the ownership, use, licensing, lease, installation, or performance of intellectual property.”

HB 40 separately clarifies the Business Court’s authority to render decisions on arbitration matters. Parties that otherwise have standing to file claims in Business Court will be permitted to use the forum to enforce arbitration agreements, appoint arbitrators, review arbitral awards or seek other judicial relief authorized by an arbitration agreement.

While the above amendments to the Business Court’s jurisdictional scope are significant, HB 40 was almost more expansive. The initial version of the Bill would have extended the Business Court’s jurisdiction to also capture insurance and indemnity contract matters, “fundamental business transactions” involving mergers and similar large corporate asset transactions, certain large banking litigations, malpractice claims filed by corporate clients and multidistrict litigation (MDL) transfer cases. However, HB 40 was repeatedly revised in committee and through the legislative process to land on a much-narrowed change in the law, at least for now.

Other Substantive Changes to Texas State Laws

HB 40 includes other amendments to Texas state laws affecting the rights and obligations of parties seeking to litigate in the Business Court. Some of the more notable such amendments are addressed below.

Venue: The Bill expressly permits parties to amend their governing documents to designate venue for Business Court matters involving derivative proceedings, governance or internal affairs disputes, fiduciary duty claims against certain corporate persons and other actions arising out of the Business Organizations Code.

Exclusion of Consumer Actions: The Bill prohibits parties from filing state and federal consumer claims in Business Court, even if supplemental jurisdiction may otherwise exist. This amendment essentially prevents large consumer class actions from flooding the Court’s gates.

Expansion of Injunctive Relief Procedure: A new provision is added to the Texas Civil Practice & Remedies Code allowing parties to seek writs of injunction from another Business Court judge if the appointed judge is unavailable to timely consider and implement the writ’s purpose.

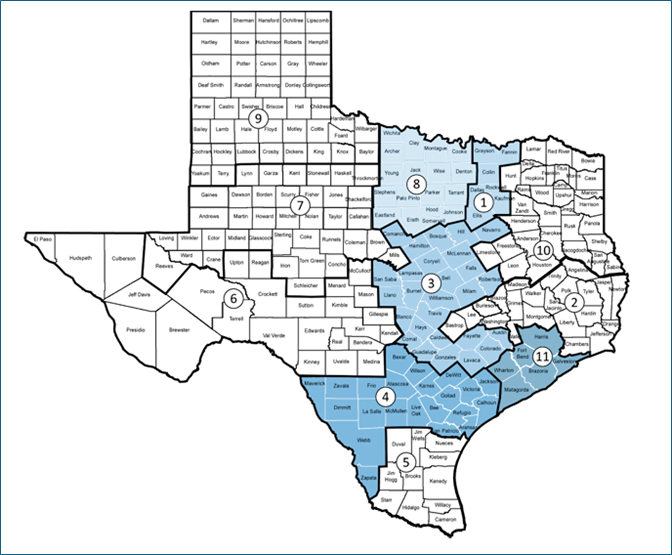

Montgomery County Moves Division: Montgomery County (covering Conroe, The Woodlands and other areas north of Houston) is being transferred out of the non-operational Second Business Court Division and added to the Eleventh Business Court Division (Houston). Houston — as well as Dallas — has notably received a large share of the new case filings in the opening months of the Court’s existence.

Preserving Rural Business Court Divisions: The legislature modified statutory sunsetting language from the Business Court Act to preserve the six non-operational divisions of the Business Court — namely the Second, Fifth, Sixth, Seventh, Ninth and Tenth Divisions (color-coded in the white regions of the map below).2

Context: New Industry Pressure in Delaware Increases Appeal for Texas Court System

The Texas Legislature’s passaContext: New Industry Pressure in Delaware Increases Appeal for Texas Court Systemge of HB 40 — less than a month after passing another business-friendly amendment to the Texas Business Organizations Code (SB 29) — comes at a time of significant scrutiny as to whether Delaware remains the premier state for incorporation and corporate governance.

While Delaware has long been the preferred forum for resolving internal governance and fiduciary matters, recent backlash from institutional investors and industry group advocates has highlighted perceived shortcomings in the Delaware Chancery Court. The Delaware Legislature has tried to step in to curb the noise, including by amending the Delaware General Corporation Law to add new safe harbor protections for controlling stockholder transactions, exculpating controlling shareholders from liability for alleged breaches of the duty of care, and implementing limits on shareholder books and records requests.

The national discourse continues nonetheless. In fact, the same week that HB 40 made its final rounds through the Texas Legislature, a Stanford Law School study3 also made rounds through corporate boardrooms, again questioning outcomes out of the Delaware Chancery Court. The study specifically found that the Chancery Court system has increasingly allowed large fee multipliers for plaintiffs’ attorneys, often exceeding 10 times the lodestar, at higher rates than observed in cases out of the federal court system. These findings have prompted renewed criticism from corporate governance groups and further calls for reform.

The growing tension in Delaware should ultimately increase the appeal of Texas and its alternative corporate governance system.

Conclusion

The Texas Legislature was busy this session expanding corporate protections and enhancing its Business Court system. The enactment of HB 40 specifically helps Texas build out its Business Court framework by refining jurisdictional standards and procedural mechanisms to expand access to the Court. Importantly, the statutory changes this session may require corporate parties to revise their governance documents and contracts to take full advantage of these laws. Katten attorneys across multiple practice groups continue to closely monitor developments and to counsel clients on invoking new protections provided by the legislature.

[1] The Texas Legislature enacts HB 40 just weeks after passing Senate Bill 29 (SB 29) — which previously expanded the Business Court’s jurisdiction over corporate governance matters and also extended related litigation protections to domestic entities. See Texas Governor Signs New Business-Friendly Governance Law to Promote In-State Corporate Growth: Senate Bill 29 Analysis, Katten (May 14, 2025), available at https://natlawreview.com/article/texas-governor-signs-new-business-friendly-governance-law-promote-state-corporate.

[2] See Texas Business Court Divisions Map, Tex. Judicial Branch, available at https://www.txcourts.gov/media/1458995/texas-business-court-divisions-map.pdf.

[3] Grundfest, Joseph A. and Dor, Gal, Lodestar Multipliers in Delaware and Federal Attorney Fee Awards (April 30, 2025), available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5237545.

Jurisdiction Affirmed: Trademark Ripples Reach US Shores

Addressing for the first time the issue of whether a foreign intellectual property holding company is subject to personal jurisdiction in the United States, the US Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit reversed a district court’s dismissal and determined that the holding company, which had sought and obtained more than 60 US trademark registrations, had sufficient contacts with the US to support exercise of personal jurisdiction. Jekyll Island-State Park Auth. v. Polygroup Macau Ltd., Case No. 23-114 (11th Cir. June. 10, 2025) (Rosenbaum, Lagoa, Wilson, JJ.)

Polygroup Macau is an intellectual property holding company registered and headquartered in the British Virgin Islands. Jekyll Island is a Georgia entity that operates the Summer Waves Water Park and owns a federally registered trademark for the words SUMMER WAVES. In 2021, Jekyll Island discovered that Polygroup Macau had registered nearly identical SUMMER WAVES marks. After Polygroup Macau asked to buy Jekyll Island’s domain name, summerwaves.com, Jekyll Island sued Polygroup Macau for trademark infringement and to cancel Polygroup Macau’s marks. The district court dismissed the case for lack of personal jurisdiction, finding that “the ‘causal connection’ between Polygroup Macau’s activities in the United States and Jekyll Island’s trademark claims was too ‘attenuated’ to support personal jurisdiction.” Jekyll Island appealed.

The Eleventh Circuit reviewed whether personal jurisdiction was proper under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 4(k)(2), also known as the national long-arm statute. Rule 4(k)(2) allows courts to exercise personal jurisdiction over foreign defendants that have enough contacts with the US as a whole, but not with a single state, to support personal jurisdiction. To establish personal jurisdiction under Rule 4(k)(2), a plaintiff must show that:

Its claim arises under federal law.

The defendant is not subject to jurisdiction in any state’s courts of general jurisdiction.

“[E]xercising jurisdiction is consistent with the United States Constitution and laws.”

The parties agreed that the first two elements were satisfied; the only dispute was whether the exercise of jurisdiction was consistent with due process.

The Eleventh Circuit noted that in the patent context, the Federal Circuit determined that a foreign defendant that “sought and obtained a property interest from a U.S. agency has purposefully availed itself of the laws of the United States.” The Eleventh Circuit found that a trademark registration is even stronger than patent rights because a “trademark registrant must show that he is already using the mark in U.S. commerce to identify and distinguish goods or intends to soon.” Polygroup Macau had more than 60 registrations and allowed other companies and customers to use those marks, which was enough to establish that it had sought out the benefits afforded under US law.

Additionally, while Polygroup Macau did not license its trademark rights, it permitted other related companies to use the SUMMER WAVES trademark to identify their products. Products marked with Polygroup Macau’s registered mark were sold in the US through dozens of retailers. Although there were no formal written agreements, the Eleventh Circuit found that Polygroup Macau exercised some degree of control over the marks. And, since the trademark rights themselves flowed from the mark’s use in domestic commerce, the Court found that Polygroup Macau “should have known that [the marks] would be used in United States commerce by related Polygroup companies.” The Court found that Polygroup Macau’s actions, taken together, displayed its attempts to exploit the US market and supported a finding of personal jurisdiction.

Finally, the Eleventh Circuit concluded that allowing related entities to use the marks was sufficiently related to the underlying trademark infringement action and found that requiring Polygroup Macau to appeal in a Georgia court was not unfair.

Artificial Doubt: Predictive Challenges to Image Evidence in the Age of AI and the Legacy of Digital Photographic Authentication

This article examines the emergent legal strategy of challenging the authenticity of visual evidence by claiming it was generated or altered by artificial intelligence (AI). Building on the historical trajectory of digital photography’s acceptance in courtrooms, it predicts a growing trend wherein defendants assert “AI fakery” as a form of reasonable doubt, even when logically implausible. The analysis draws upon precedents that guided the judicial reception of digital imagery, anticipating how similar legal tests may be adapted to confront the uncertainty that generative AI introduces. The rapid advancement of AI, as seen with the June 2025 release of Google’s Veo 3, may create an environment of potentially conflicting judicial decisions as the technology continues to evolve.

Introduction

As generative artificial intelligence matures, it brings with it a crisis of confidence in the authenticity of digital media. Yan (2023) argues that, as part of the evolution of defense challenges, the legitimacy and reliability of evidence can be a catalyst for judicial review. This article argues that such claims, regardless of their merit, will become a strategic lever for sowing doubt in juries, much like early objections to digital photography. By reviewing judicial approaches to photo admissibility in the digital era, a reasonable prediction of convergence will reshape how courts handle visual evidence allegedly tainted by AI manipulation.

The Rise of Digital Photo Skepticism in the Courts

The skepticism surrounding visual evidence is not a new phenomenon. In the 1990s and early 2000s, courts struggled with whether digital photographs could be reliably authenticated, given the ease of digital image manipulation. Early opinions show judicial hesitation. In State v.

Swinton (2004), the Connecticut Supreme Court reviewed the use of computer-generated images in forensic comparison and emphasized the need for a strong foundational showing of accuracy and reliability. The court demanded rigorous expert testimony to validate the process through which the images were produced.

Similarly, in United States v. Habershaw (Cole et al., 2015), the court admitted a digital image but required the proponent to demonstrate the chain of custody and technical reliability. These cases reflect a period when the authenticity of digital images was contested not only by technical challenges but also by a latent judicial unfamiliarity with the medium.

Yet by the 2010s, courts routinely accepted digital photographs, assuming their reliability, absent specific claims of tampering. In United States v. Anderson (United States v. Anderson, 2010), the courts held that “{a} photograph may be authenticated based on the testimony of a witness familiar with the scene depicted and accuracy of the image, even if the photograph is digital.” The focus has shifted from technological origin to contextual trustworthiness, a key pivot point that AI-generated evidence now threatens to undermine in reverse.

Generative AI and the Reemergence of Conscious Doubt

Deepfakes and other generative tools have placed us at another inflection point. Defense strategies are increasingly incorporating the question of whether a photo or video has been manipulated by AI, despite evidence to the contrary. Defense attorneys may begin to involve the specter of AI-generated forgeries to challenge the evidentiary integrity of images. Unlike prior challenges grounded in demonstrable technological limits, these objections are often rhetorical, leveraging juror unfamiliarity with AI to cast probabilistic doubt.

Jurors today may be particularly vulnerable to doubt when defense attorneys suggest that key evidence—especially images, audio, or video—could have been artificially generated using AI. Similar to the “CSI effect,” which skews juror expectations by portraying forensic evidence as infallible on television, the “AI doubt effect” may cause jurors to overestimate the plausibility of fabrication. Even without technical proof, merely introducing the possibility that a piece of evidence could be deepfaked or algorithmically altered may erode trust in its authenticity. This tactic exploits both the novelty and perceived mystery of artificial intelligence, prompting jurors to question evidence that would otherwise seem conclusive. As AI continues to advance, the courtroom may see a shift from questioning the integrity of investigators to questioning the integrity of reality itself. The result could be a chilling effect on prosecutions that rely on digital evidence unless courts develop clearer standards for authenticating media in the era of AI.

The legal system has already signaled its discomfort with AI-manipulated media. In United States v. Thomas (USA V. Thomas, No. 22-60367 (5th Cir. 2023), 2023), prosecutors were compelled to preemptively authenticate surveillance footage amid claims that it might have been generated by artificial means. Though the court ultimately admitted the evidence, the mere presence of such an objection illustrates a strategic pivot: invoking AI is no longer about proving fakery but about invoking its plausibility to unseat credibility.

Predictive Analysis: The AI-Evidence Paradigm Will Follow the Digital Photography Trajectory

Much like early digital photo cases, courts will need to resolve three emerging doctrinal issues: (1) the standard for authenticating AI-susceptible evidence; (2) the threshold for allowing “AI manipulation” objections to proceed; and (3) the weight such arguments should carry in jury deliberation.

Authentication:

Under Federal Rule of Evidence 901 (a) (Rule 901. Authenticating or Identifying Evidence, n.d.), the evidence must be “sufficient to support a finding that the item is what the proponent claims it is.” As a flexible standard, it has historically allowed for witness testimony or metadata. However, in the age of generative AI, this may no longer suffice. Courts may demand technical certification or expert validation-akin to the Swinton approach-especially if the defense invokes AI manipulation as a potential threat.

Objection Threshold:

Objections based solely on speculation that AI might have been involved, without affirmative evidence, risk clogging the judicial process. The court will likely adopt a gatekeeping function similar to that in Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., (Daubert V. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 509 U.S. 579 (1993), n.d.), requiring defense assertations to meet a preliminary showing of plausibility before triggering extensive evidentiary hearings.

Jury Perception and Prejudicial Impact:

As with early digital photography cases, there is a risk that jurors, influenced by media portrayals of AI’s capabilities, will overestimate the ease of deepfake production. Courts must weigh the Rule 403 (Rule 403. Excluding Relevant Evidence for Prejudice, Confusion, Waste of Time, or Other Reasons, n.d.) danger of undue prejudice, as speculative claims of AI fakery may distort rational deliberation. Instructions clarifying the burden of proof and cautioning against technological speculation may become standard in trials involving digital imagery.

Preemptive Doctrinal Solutions

To prevent the erosion of evidentiary trust, courts, and legislatures must act proactively. The judicial system could establish a rebuttable presumption of authenticity for images with clear metadata, a chain of custody, and expert validation, placing the burden on the challenging party to offer more than mere conjecture.

Model jury instructions should evolve to include language addressing AI-related objections. For example: “The defense has raised a possibility that the image may have been altered by artificial intelligence. You may consider this claim only if you find credible evidence supporting it, not merely because such alteration is theoretically possible”.

Legal scholars have begun to call for standardized AI forensic tools. Just as photo enhancement tools gained legitimacy through peer review and industry standards, AI authentication mechanisms, such as digital provenance frameworks like Adobe’s Content Authenticity Initiative, may become part of the evidentiary protocol. A stall in this preemptive approach surrounds the inherent speed at which AI is advancing and able to avoid such authenticators.

Conclusion

The use of artificial intelligence to question the authenticity of visual evidence is not just a future concern; it is a present tactic, echoing the transitional anxiety that accompanies digital photography’s courtroom debut. Courts must apply historical wisdom, refusing all speculative doubt to supplant procedural rigor. Just as the judiciary adapted to the digital lens, it must now refine its focus to discern the real from the fabricated in an era where the line between them has never been more ambiguous.

References

Cole, K.A., Gurugubelli, D., & Rogers, M.K. (2015, May 20). A review of recent case law related to digital forensics: Proceedings of the 2015 annual ADFSL Conference on Digital Forensics, Security and Law. Daytona Beach, FL.

https://commons.erau.edu/adfsl/2015/wednesday/2/

Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 509 U.S. 579 (1993). (n.d.). Justia Law. https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/509/579/

Rule 403. excluding relevant evidence for prejudice, confusion, waste of time, or other reasons. (n.d.). LII / Legal Information Institute.

https://www.law.cornell.edu/rules/fre/rule_403

Rule 901. Authenticating or identifying evidence. (n.d.). LII / Legal Information Institute. https://www.law.cornell.edu/rules/fre/rule_901

State v. Swinton, 268 Conn. 781,847 A2d. 921 (2004).

https://caselaw.findlaw.com/court/ct-supreme-court/1407681.html

Yan, Q. (2023). Legal Challenges of Artificial Intelligence in the Field of Criminal Defense. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media, 30(1), 167–175. https://doi.org/10.54254/2753-7048/30/20231629

USA v. Thomas, No. 22-60367 (5th Cir. 2023). (2023, January 6). Justia Law. https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/appellate-courts/ca5/22-60367/22-60367-2023- 01-06.html

United States v Anderson, No. 09.1733,618 F.3d 873 (8th Cir. 2010) https://caselaw.findlaw.com/court/us-8th-circuit/1536307.html

Justice Kavanaugh Signals One Conservative Vote in Labcorp Toward Imposing a Pre-Certification Standing Requirement Under FRCP 23

On June 5, 2025, the Supreme Court declined to decide the question, certified in Laboratory Corp. of America Holdings v. Davis, as to “[w]hether a federal court may certify a class action pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23(b)(3) when some members of the proposed class lack any Article III injury.” The Court instead dismissed the case as improvidently granted, due to apparent procedural complexities in how the case was presented on appeal.

Justice Kavanaugh nonetheless weighed in. In a lone dissenting opinion, Kavanaugh made clear where he stands, concluding that “Rule 23 and this Court’s precedents make this a straightforward case” requiring standing questions to be decided at the pre-certification stage of class proceedings. Specifically, “a federal court may not certify a damages class that includes both injured and uninjured members. Rule 23 requires that common questions predominate in damages class actions. And when a damages class includes both injured and uninjured members, common questions do not predominate.”

Kavanaugh’s dissenting opinion separately laments the “serious real-world consequences” and undue pressure that inflated, overbroad classes place on defendants—often “coerc[ing] businesses into costly settlements that they sometimes must reluctantly swallow rather than betting the company on the uncertainties of trial.”

While Kavanaugh’s position presumably conforms with many of the other conservative justices, the Court’s per curiam order dismissing the case leaves a current circuit split intact for now as to the proper resolution of standing questions at the pre-certification stage. The question should soon be presented to the Court again on a cleaner procedural vehicle rising through the appellate courts.

“Overbroad and incorrectly certified classes threaten massive liability—here, with potential damages up to about $500 million per year. That reality in turn can coerce businesses into costly settlements that they sometimes must reluctantly swallow rather than betting the company on the uncertainties of trial. . . . . [T]he coerced settlements substantially raise the costs of doing business. And companies in turn pass on those costs to consumers in the form of higher prices; to retirement account holders in the form of lower returns; and to workers in the form of lower salaries and lesser benefits. So overbroad and incorrectly certified classes can ultimately harm consumers, retirees, and workers, among others. Simply put, the consequences of overbroad and incorrectly certified damages class actions can be widespread and significant.” (Kavanaugh, J., dissenting)

OVER THE HILL: Litigator Adean Hill Jr. Just Can’t Seem to Get Service Accomplished

TCPAWorld has a bunch of little side stories in addition to all the big ones.

Here’s a quick one for you.

In Adean Hill v. Amity One Tax, 2025 WL 1592957 (N.D. Tex. June 5, 2025) the Court gave Hill one last chance to serve the complaint on the defendant.

Backing up, the case has been around for a while and the court had already given Hill until May 29, 2025 to get the complaint served. But that date passed without service.

Instead Hill filed a motion for substituted service–to permit service by mail– but that is a method of service already permitted in Texas apparently, so the motion was unnecessary. Then again his motion lacked a sworn statement of his previous efforts to serve Amity, so it would have been denied regardless.

Still the court gave him until July 7, 2025 to accomplish service. Let’s see if he pulls it off.

I know, weird one. But the idea of a litigator struggling with the basics of serving a complaint tells you what you’re dealing with out there at times.

A New Gateway for Cross-Border Enforcement: Hague Judgments Convention Comes into Effect in the UK on 1 July 2025

The Hague Convention of 2 July 2019 on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Judgments in Civil and Commercial Matters (the “Hague Judgments Convention”) will come into effect in the UK on 1 July 2025. The process of enforcing UK judgments[1] in other contracting states (including all EU Member States (except Denmark), Ukraine and Uruguay) will now be far more streamlined in most cases, thereby reducing the delay, cost and uncertainty of enforcement in those jurisdictions.

While the entry into force of the Hague Judgments Convention in the UK is a welcome step in the facilitation of cross-border dispute resolution, particularly post-Brexit, there are some notable limitations to its scope. For instance, it does not provide for the automatic recognition and enforcement of relevant judgments, judgments must meet certain requirements, and it will apply only to UK judgments where the underlying proceedings were commenced on or after 1 July 2025.

Scope and purpose of the Hague Judgments Convention

The Hague Judgments Convention provides a uniform and simplified legal framework for the reciprocal recognition and enforcement of judgments in civil and commercial matters across contracting states, without the need to re-examine the substance of the case in fresh proceedings (provided that certain criteria are met; see below). For example, only a specified group of documents will need to be produced in every case[2].

Importantly, the Hague Judgments Convention applies to judgments where the dispute falls within both exclusive and non-exclusive jurisdiction clauses (in contrast to the 2005 Hague Convention[3], for example, which applies only to exclusive choice of court agreements), making it widely applicable to many cross-border contracts.

A broad range of civil and commercial matters are within its scope, including both contractual and tort claims. Several types of cases are excluded, however, including: status and legal capacity of natural persons; family law; defamation; insolvency; tax; customs; revenue; administrative law matters; anti-trust; privacy; activities of armed forces; carriage of passengers and goods; and intellectual property matters[4]. Arbitration and related proceedings are also expressly excluded[5].

Eligibility criteria for recognition and enforcement and other limitations

There are several limitations as to the scope and applicability of the Hague Judgments Convention, which will apply only to UK judgments where the underlying proceedings were commenced on or after 1 July 2025.

Notably, it does not provide for the automatic recognition and enforcement of judgments, unlike the simplified EU regime[6]. To be eligible for recognition and enforcement, a judgment must fall within one of the specified bases[7]. These include (but are not limited to) the defendant: having expressly submitted to the jurisdiction of the court of origin; having been habitually resident in the state of origin at the time it became a party to the relevant proceedings; or having had their principal place of business in the state of origin at the time it became a party to the proceedings, with the dispute arising out of activities of that business.

Recognition and enforcement may be refused in certain (relatively limited) cases. These include cases where: (1) a judgment has been obtained by fraud; (2) the defendant was not notified of the proceedings in sufficient time to arrange a defence; (3) recognition would be manifestly incompatible with public policy of the state in which enforcement is requested; (4) a judgment is inconsistent with a judgment given by a court of the requested state in a dispute between the same parties; or (5) a judgment is inconsistent with an earlier judgment given by a court of another state between the same parties on the same subject matter[8]. Any refusal by the requested state to enforce a judgment under the Hague Judgments Convention does not prevent a subsequent application for recognition or enforcement of the judgment in that state, however.

Further, the law of the requested state (i.e. the country in which recognition and enforcement is sought) governs the applicable procedure (unless the Hague Judgments Convention provides otherwise). This is likely to introduce some uncertainty around timing and process, albeit the relevant court is still required to act expeditiously[9]. Any pre-existing treaties to which a contracting state is a party will also continue to apply, although the contracting states must as far as possible interpret the Hague Judgments Convention to be compatible with any other treaties that are in force[10].

Geographic reach: other contracting states

The Hague Judgments Convention has broad geographic reach (where matters fall within its scope).

As at the date of publication (June 2025), contracting states include all EU Member States (except Denmark), Ukraine and Uruguay (and the UK from 1 July 2025) [11].

Albania, Andorra and Montenegro each have ratified the Hague Judgments Convention, where it is expected to come into force in 2026[12]. Meanwhile, the United States, Israel, Costa Rica, Kosovo, North Macedonia and Russia have all signed the Hague Judgments Convention, thus signalling an intention to join, although those states will not be bound until they ratify it.

Significance for the UK and its judicial system

Since leaving the EU, the UK has not benefited from certain mechanisms that facilitate cross-border enforcement of civil judgments across EU Member States, such as the Brussels I Recast Regulation 2015 (“Brussels Recast 2015”) and the Lugano Convention 2007. For example, Brussels Recast 2015 provided for automatic recognition of judgments across EU Member States without the need for a declaration of enforceability.

Since the end of the post-Brexit transition period on 31 December 2020, enforcement of UK judgments has followed the domestic rules in – and (where applicable) bilateral agreements with – overseas jurisdictions, all of which vary and can lead to legal uncertainty and increased costs.

The Hague Judgments Convention helps to fill this post-Brexit enforcement gap to some extent – albeit with the caveat that (as noted above) it does not provide for the automatic recognition and enforcement of judgments as does the simplified EU regime.

Accordingly, while the Hague Judgments Convention (re)strengthens the attractiveness of the UK as a forum for resolving international commercial disputes by providing a reliable enforcement mechanism in participating countries, it remains to be seen how the courts of contracting states will apply it in practice in terms of both procedure and any pre-existing treaties in place.

Conclusion

The entry into force of the Hague Judgments Convention in the UK is a welcome step in the facilitation of cross-border dispute resolution, particularly post-Brexit. The clear and streamlined framework for the recognition and enforcement of judgments across other contracting states will be of benefit to businesses and individuals who are engaged in international commerce and who wish to rely upon the UK courts to uphold their legal rights. Despites its limitations, the Hague Judgments Convention is still expected to improve legal efficiency and enhance enforcement predictability, whilst also reinforcing the UK’s position as a global legal hub.

[1] I.e. Judgments issued by the courts of England & Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland.

[2] Article 12.

[3] Hague Convention of 30 June 2005 on Choice of Court Agreements.

[4] Article 2.

[5] Article 2(3)).

[6] E.g. under the Brussels I Recast Regulation 2015; see further below.

[7] Article 5.

[8] Article 7.

[9] Article 13(1).

[10] Article 23.

[11] Contracting states at the time of publication are: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, European Union, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Ukraine and Uruguay. For the latest status, see: https://www.hcch.net/en/instruments/conventions/status-table/?cid=137 (links to a third party website).

[12] On 1 March 2026 in Albania and Montenegro; and on 1 June 2026 in Andorra.

SCOTUS Declines to Decide Fate of Classes with Uninjured Members: 8-1 Decision in LabCorp Leaves Unresolved Whether Rule 23 Allows Certification for a Class Containing Members Who Lack Standing

The United States Supreme Court, in an 8-1 decision on June 5, 2025, dismissed the highly anticipated case of Laboratory Corporation of America Holdings v. Davis as “improvidently granted.” Laboratory Corporation of America Holdings, dba Labcorp, v. Luke Davis, et al., No. 22-55873. The decision, or lack thereof, sidesteps a critical question for class action litigation: whether a damages class can be certified under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23 when it includes individuals who have not suffered any actual injury.

LabCorp was challenging a Ninth Circuit decision that allowed the certification of a massive class of visually impaired individuals under California’s Unruh Civil Rights Act. Cal. Civ. Code. § 51. The suit alleged LabCorp’s check-in kiosks were inaccessible, triggering statutory damages of $4,000 per violation. With a class size potentially in the hundreds of thousands, the exposure was astronomical—a classic case of “bet the company” litigation.

Background of the Case

LabCorp is a clinical diagnostic laboratory that tests samples collected from patients at its patient service centers. In a suit filed before the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California, a group of legally blind and visually impaired individuals sued LabCorp under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the Unruh Civil Rights Act, alleging that the company’s self-service check-in kiosks were inaccessible. The District Court certified a damages class consisted of “[a]ll legally blind individuals in California who visited a LabCorp patient service center in California during the applicable limitations period and were denied full and equal enjoyment of the goods, services, facilities, privileges, advantages, or accommodations due to LabCorp’s failure to make its e-check-in kiosks accessible to legally blind individuals.”

LabCorp filed a petition under Rule 23(f)’s interlocutory appellate procedure, contending that the class encompassed uninjured individuals.

While LabCorp’s petition was pending, the District Court clarified the class definition, explaining that the class included “[a]ll legally blind individuals who . . . , due to their disability, were unable to use” LabCorp kiosks.

Subsequently, the Ninth Circuit granted LabCorp’s Rule 23(f) petition. LabCorp’s key argument was that the class was fatally overly broad and swept in countless individuals who may have never intended to use a kiosk in the first place, and thus suffered no actual injury. The Ninth Circuit relying on its opinion in Olean Wholesale Grocery Coop., Inc. v. Bumble Bee Foods LLC, 31 F.4th 651, 665 (9th Cir. 2022), held that a class can be certified even if it includes “more than a de minimis number of uninjured class members.”

Supreme Court Proceedings

The Supreme Court initially granted certiorari to address the question of “[w]hether a federal court may certify a class action pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23(b)(3) when some members of the proposed class lack any Article III injury.” However, after oral arguments, the Court dismissed the case in a one-line order, without ruling on the merits, stating that the writ of certiorari was “improvidently granted.”

Justice Kavanaugh’s Dissent

Justice Kavanaugh dissented from the dismissal, expressing that the Court should have addressed the merits. He argued (correctly) that certifying a damages class containing uninjured members is inconsistent with Rule 23, which requires that common questions of law or fact predominate in class actions. Notably, Kavanaugh also emphasized the risk from “[c]lasses that are overinflated with uninjured members rais[ing] the stakes for businesses that are the targets of class actions.” He went on to underscore that certifying such classes “can coerce businesses into costly settlements that they sometimes must reluctantly swallow rather than betting the company on the uncertainties of trial.”

“Classes that are overinflated with uninjured members raise the stakes for businesses that are the targets of class actions.”

The Circuit Split

This decision effectively leaves undisturbed the split in authorities that has existed since the Supreme Court’s decision in TransUnion LLC v. Ramirez, 594 U.S. 413, 431 (2021). In TransUnion, while the Supreme Court held that “[e]very class member must have Article III standing in order to recover individual damages,” it did not decide when a class member’s standing must be established and whether a class can be certified if it contains uninjured class members. Subsequently, while some courts have denied class certification if there are uninjured class members, other courts have found it appropriate to address a class member’s standing after certification.

LabCorp, in its petition for certiorari, addressed the “three camps” of opinions:

Circuits holds that a class may not be certified where it includes members who have suffered no Article III injury (the Second Circuit, Eighth Circuit, and some courts in the Fifth and Sixth Circuits);

Circuits that have strictly applied Rule 23(b)(3)’s predominance requirement to reject classes that contain more than a de minimis number of uninjured members (the D.C. Circuit and the First Circuit); and

Circuits that have held that the presence of uninjured class members should not ordinarily prevent certification (the Ninth Circuit, Seventh Circuit, and Eleventh Circuit).

In light of the majority opinion, this question remains unresolved.

Beijing IP Court Releases 2024 Annual Cases

On April 30, 2025, the Beijing IP Court (BIPC) released their list of 2024 annual cases including 7 IP-related cases and 1 antitrust case. The Court explained that the cases “cover the four major intellectual property trial areas of patents, trademarks, copyrights, and competition and monopoly, involving innovative achievements in emerging industries in key areas such as medicine, communications, seed industry, platform economy and data. These cases reflect five major characteristics: increasing efforts to protect industrial innovation in key areas, cracking down on intellectual property infringements, helping to build a high-level socialist market economic system, serving the development of the intellectual property rule of law, and contributing Chinese wisdom to world intellectual property governance.”

Press conference releasing the 2024 annual cases.

The original text is available here via social media as the BIPC seems to be geoblocked as of the time of writing.

As summarized by the BIPC:

Case Ⅰ: Standard-Essential Patent Infringement and Royalty Rate Dispute——Assisting a Renowned Enterprise in the Communications Field to Reach a Global Settlement1. Case InformationPlaintiff: X CompanyDefendant: X Guangdong Mobile Communications Company.2. Basic FactsBoth parties to this case are renowned enterprises in the field of communications. At the time of this trial, the two parties had been engaged in licensing negotiations for many years over the 3G and 4G standard – essential patent portfolios, and there were numerous related parallel litigations in various jurisdictions globally, including infringement claims and tariff claims. The plaintiff is the holder of the invention patent titled ‘Base Station Device, Mobile Station Device and Communication Method’. It claims that the patent involved is a standard – essential patent of the LTE communication standard, and believes that the defendant’s acts of manufacturing, selling and offering for sale the two models of mobile phones involved constitute an infringement of the patent right involved, and requests the court to order the defendant to stop the infringing acts.The plaintiff did not file a claim for damages and stated that the purpose of its lawsuit was to advance the licensing negotiations. The defendant filed a counterclaim in the dispute over the royalties of the standard essential patents in this case, requesting the court to make a judgment on the licensing conditions, including but not limited to the licensing royalties, within the scope of mainland China for the 3G and 4G standard essential patents which the plaintiff owns and has the right to license for the intelligent terminal products manufactured and sold by the defendant. After trial, the Beijing Intellectual Property Court held that the counterclaim filed by the defendant met the acceptance conditions, thereby accepted the defendant’s counterclaim and actively promoted the joint trial of the two lawsuits, and finally facilitated the two parties to successfully reach a global patent cross – licensing agreement. On the same day, the parties applied for the withdrawal of this case and the counterclaim respectively on the grounds of reaching a settlement, and the Beijing Intellectual Property Court ruled to approve the withdrawal of the lawsuit by both parties.3. Judgment GistWhen a standard-essential patent holder files a patent infringement lawsuit, requesting the court to order the implementer to stop infringing the patent involved, and the implementer files a counterclaim, requesting the court to rule on the licensing conditions of the standard – essential patent portfolio including the patent involved, the court may take into account the fact that both the counterclaim and the original claim need to examine the same fact, that is, the licensing negotiation matters between the patent holder and the implementer regarding the patent involved and the related standard – essential patent portfolio.The counterclaim should be accepted and jointly tried, in a situation where there is a high degree of correlation between the counterclaim and the original claim.4.Typical SignificanceUnder civil procedure law theory, the relationship between the counterclaim and the original claim serves as the basis for their joint trial. The closer the substantive legal relationship between the original claim and the counterclaim, the more necessary it is to jointly try them in the same case. Article 233 of the “Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court Concerning the Application of the Civil Procedure Law of the People’s Republic of China (Amended in 2022)” (referred to as the Judicial Interpretation Concerning the Civil Procedure Law) stipulates the acceptance conditions for counterclaims, stating that if the counterclaim and the original claim are based on the same legal relationship, there is a causal relationship between the claims, or the counterclaim and the original claim are based on the same fact, the people’s court should jointly try them. Generally, the counterclaims and original claims accepted by the people’s court are based on the same legal relationship or the same fact, but there are certain particularities in the field of standard – essential patents.A patent that must be used to implement a certain technical standard is called a standard-essential patent. With the vigorous development of the digital economy, standard-essential patent technologies are widely applied in fields such as mobile communication, intelligent connected vehicles, and the Internet of Things. A smart terminal product often contains thousands of standard – essential patents. Against the backdrop of intensified market competition and accelerated technological iteration, licensing negotiations and disputes surrounding standard-essential patents are increasing day by day. In a standard-essential patent infringement case, the right basis usually only involves one or several patents, and the alleged infringing product is also specific. However, in actual licensing negotiations, the two parties often conduct negotiations concerning the entire standard – essential patent portfolio of the patent holder and all related products of the implementer. This leads to a situation where a standard – essential patent infringement lawsuit and a royalty rate lawsuit are not consistent in the scope of patents and products involved. So, on the surface, it does not meet the general acceptance conditions for counterclaims in the civil procedure law. This is exactly the case in this lawsuit. Based on this, the Company claimed that the counterclaim filed by the Mobile Communications Company should not be accepted, and further claimed that the original claim and the counterclaim did not involve the same fact because it did not request the calculation and payment of infringement damages based on the licensing fees in this case.In response to this claim, the court referred to the previous judicial practice of standard – essential patent trials, comprehensively considered the trial ideas and judgment logic of standard – essential patent infringement lawsuits and royalty rate lawsuits, and held that in an infringement lawsuit involving standard-essential patents, whether to order the defendant to stop the infringement is not only determined by whether the defendant has implemented the patent involved without permission, but also by whether the negotiating parties have violated the FRAND obligation. To determine whether the patent holder has violated the FRAND licensing obligation and whether the implementer has violated the obligation of good faith negotiation, in addition to examining the negotiating behaviors of both parties, it is also necessary to examine whether the licensing conditions proposed by both parties during the negotiation process are obviously unreasonable. These licensing conditions are not only for the patent involved, but for all 3G and 4G standard-essential patents for which the X Company has the right to grant licenses. To determine whether the licensing conditions proposed by both parties are obviously unreasonable, it is necessary to determine the reasonable range of licensing conditions, and the trial content of the royalty rate lawsuit for standard-essential patents is exactly the licensing conditions.Based on this special trial logic, although the counterclaim and the original claim in this case are not based on the same legal relationship, there is a causal connection between them, and both are closely related to the fact of the licensing negotiation between the two parties. On this basis, the Beijing Intellectual Property Court held that the the counterclaim should be accepted and jointly tried.The acceptance of the counterclaim aligns with the interests of the parties, which was mutually acknowledged by both sides. The essence of standard -essential patent disputes is to promote negotiation consensus through litigation confrontation, and seek negotiation benefits through litigation procedures. In this case, on the one hand, the patent holder has already initiated an infringement lawsuit and sought injunctive relief in advance, on the other hand, the patent implementer hopes that the court will rule on the licensing conditions. If the counterclaim of the patent implementer is not accepted, it can only initiate another subsequent lawsuit, and a new lawsuit may still need to go through complex and time-consuming procedures such as service of process in foreign-related cases and objections to jurisdiction. This is not only inefficient, but also the sequence and speed of the two lawsuits may affect the negotiating positions of the two parties. Facts have proved that the joint trial of the two lawsuits promoted the two parties to successfully reach a global cross-licensing agreement and subsequent cooperation plan, which resolved the long-standing patent disputes between the two parties and achieved a win-win cooperation between the two parties.This case not only delves deep into the application of the law and clarifies the conditions for the joint trial of a standard-essential patent infringement lawsuit and a counterclaim for standard-essential patent royalties, but also adheres to the judicial concept of “promoting negotiation through trial and substantially resolving disputes”, promoting the substantial resolution of disputes, maximizing the interests of both parties, and promoting industrial licensing. The fair and efficient trial of this case demonstrates the high level and professionalism of China’s judicial protection of intellectual property rights, and reflects the wisdom and responsibility of Chinese courts in the new era in resolving international disputes, as a useful reference for the trial of similar cases in the future.