BREAKING: Todd Snyder to Pay Six Figure Fine for Consumer Privacy Violations

The California Privacy Protection Agency (CPPA) has taken decisive enforcement action against national clothing retailer Todd Snyder, Inc., highlighting the increasing scrutiny businesses face under the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA). In a release published May 6, 2025, the CPPA announced that the retailer will pay a $345,178 fine and make significant changes to its privacy practices following findings of non-compliance with state privacy laws.

According to the CPPA, Todd Snyder failed to properly configure its privacy portal, resulting in a 40-day window during which consumers’ requests to opt out of the sale or sharing of personal information were not processed. This technical lapse was compounded by procedural missteps: consumers were required to submit more information than was necessary to fulfill privacy requests, including needing to verify their identity before opting out.

In addition to the monetary penalty, Todd Snyder has agreed to reconfigure its opt-out mechanism to ensure effective functioning. The company will also provide CCPA compliance training for its employees.

The CPPA emphasized that businesses are responsible for ensuring their privacy management solutions comply with the law and function as intended. Using a consent management platform does not absolve a business from compliance obligations.

“Businesses should scrutinize their privacy management solutions to ensure they comply with the law and work as intended, because the buck stops with the businesses that use them,” said Michael Macko, head of the CPPA’s Enforcement Division.

This action is part of a broader wave of privacy enforcement. The CPPA recently imposed a $632,500 penalty on American Honda Motor Co. for similar violations and launched the bipartisan Consortium of Privacy Regulators to collaborate with states across the country to implement and enforce privacy laws nationwide.

You can read the CPPA’s press release here: CPPA Announcement

STUNNING ROBOCALL SPIKE After Months of Decline Robocalls Spike to New High In April, 2025

This is not good news.

Through the hard work of R.E.A.C.H., and others, robocall volumes dropped continuously through all of 2024.

The result–over 2 billion less calls in 2023 than in 2024!

While that’s great news, 2025 has seen a massive reversal in the trend. Indeed, robocalls have been up every month this year so far.

The worst part?

April, 2025 saw the most robocalls since August, 2023!

In fact, January-April, 2025 has seen the highest volume of robocalls since the epidemic peaked in 2019.

Not good.

So what’s going on here?

We know the FCC’s TCPA one-to-one rule was shelved back in January. That may have unleashed the floodgates. Perceptions that the Trump administration–and the effort to deregulate American business– would result in less robocall enforcement may also be playing a role here.

Perhaps most striking, the volume of robocalls attributable to “telemarketing” has more than tripled since April, 2019. At that time there were approximately 539MM marketing calls.

In April, 2025– by contrast– there were 1.7BB telemarketing robocalls. In one month!

All data from YouMail’s Robocall Index (https://robocallindex.com/)

Without question, practices in the lead generation industry are contributing to this rise– as is the rise of outbound AI calling practices. One thing is clear, however: the mission of R.E.A.C.H. is more important than ever before.

Will keep a very close eye on this trend. As robocalls skyrocket again we can expect the regulators and Congress to look to pass more anti-robocall bills. (But usually they just end up making things worse.) And any prayer of tort reform– as TCPA cases shoot through the roof–now seems off the table.

Hopefully they’ll listen to the Czar and fix this mess once and for all!

SERIOUSLY?: Robotalker.com Sued in TCPA Class Action For Robocalls And Its Almost Too On the Nose

I remember when that company Sly Dial came along I thought– that name is going to get them in trouble.

But apparently somebody has developed an automated outreach platform and just went ahead and called it “Robotalker” which inadvertently seems to combine the words “robocall” and “stalker” in a very unfortunate way.

Regardless robotalker.com was just sued in a TCPA class action alleging the company made robocalls to a website visitor without consent.

Per the Plaintiff DIEDRICH THIESSEN Robotalker sent her a prerecorded voicemail back in March without her consent.

The plaintiff–represented by Manny Hiraldo– seeks to represent a class of:

TCPA Robocall Class: All persons within the United Stateswho, within the four years prior to the filing of this lawsuitthrough the date of class certification, received one or moreprerecorded voice calls regarding Defendant’s property,goods, and/or services on their cellular telephone line.

So nationwide class of everyone who received a prerecorded call regarding Robotalker’s services regardless of who made the call.

Alot of problems with this class definition, obviously, but will be interesting to see how Robotalker responds regardless.

Will keep an eye on this.

Full complaint here: predocketComplaintFile (11)

Virginia Governor Signs into Law Bill Restricting Minors’ Use of Social Media

On May 2, 2025, Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin signed into law a bill that amends the Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act (“VCDPA”) to impose significant restrictions on minors’ use of social media. The bill comes on the heels of recent children’s privacy amendments to the VCDPA that took effect on January 1, 2025.

The bill amends the VCDPA to require social media platform operators to (1) use commercially reasonable methods (such as a neutral age screen) to determine whether a user is a minor under the age of 16 and (2) limit a minor’s use of the social media platform to one hour per day, unless a parent consents to increase the daily limit.

The bill prohibits social media platform operators from using the information collected to determine a user’s age for any other purpose. Notably, the bill also requires controllers and processors to treat a user as a minor under 16 if the user’s device “communicates or signals that the user is or shall be treated as a minor,” including through “a browser plug-in or privacy setting, device setting, or other mechanism.” The bill also prohibits social media platforms from altering the quality or price of any social media service due to the law’s time use restrictions.

The bill defines “social media platform” as a “public or semipublic Internet-based service or application” with users in Virginia that:

connects users in order to allow users to interact socially with each other within such service or application; and

allows users to do all of the following:

construct a public or semipublic profile for purposes of signing into and using such service or application;

populate a public list of other users with whom such user shares a social connection within such service or application; and

create or post content viewable by other users, including content on message boards, in chat rooms, or through a landing page or main feed that presents the user with content generated by other users.

The bill exempts from the definition of “social media platform” a service or application that (1) exclusively provides email or direct messaging services or (2) consists primarily of news, sports, entertainment, ecommerce, or content preselected by the provider and not generated by users, and for which any chat, comments, or interactive functionality is incidental to, directly related to, or dependent on the provision of such content.

The Virginia legislature declined to adopt recommendations by the Governor that would have strengthened the bill’s children’s privacy protections.

These amendments to the VCDPA take effect on January 1, 2026.

Developments in Patent Subject Matter Eligibility for Software-Related Inventions, in View of Guvera v. Spotify

This article is a revised and updated version of an earlier article titled “Patent Protection for Entertainment Software Inventions” published on November 29, 2022.

Innovators seeking patent protection for software inventions should be aware that all software inventions face patent-eligibility issues.1 Nevertheless, patent practitioners who are experienced in the art of software patent prosecution can help ensure that software inventions get maximum protection.

The trial-court and appellate-court decisions in the case of Guvera v. Spotify from the Southern District of New York and the Federal Circuit demonstrate the importance of drafting patent applications for software inventions according to a clear technological problem-solution framework to avoid invalidation for having claims directed to ineligible subject matter.2

In September of 2022, Guvera, a patent owner (and former music-streaming company), lost its patent infringement case against the music-streaming giant Spotify after the Southern District of New York held that Guvera’s patent was not eligible for patent protection.3

Guvera’s patent claims involved methods of generating playlists with targeted advertising.4

The Southern District of New York held that the patent claims at issue were directed to an abstract idea, lacked an inventive concept, and were, therefore, ineligible for patent protection under 35 U.S.C. § 101 (“Section 101”).

Ever since the U.S. Supreme Court’s Alice decision in 2014, Section 101 has been used to invalidate countless software patents.5 Alice and subsequent Section-101 case law have established that patent claims for software inventions must include features that provide technological improvements.6

The Alice decision was intended, in part, to stop patents from being granted for basic and well-known concepts (i.e., abstract ideas) merely implemented by way of a generic computer.7 As the Southern District of New York noted in Guvera v. Spotify, “merely adding computer functionality to increase the speed or efficiency of the process does not confer patent eligibility.”8

Applying the Alice two-step test for subject-matter eligibility, the Southern District of New York, in Guvera v. Spotify, first determined that Guvera’s patent claims were “directed to the abstract idea of matching content using data identifiers.”9

Next, the Southern District of New York determined that the patent claims did not contain an “inventive concept” and, thus, did not add significantly more to the abstract idea of content matching because, “[a]t bottom, the claims recite the process for implementing the abstract idea of matching content on a computer,” and, “[a]t best, the patent improves the efficiency of content matching….”10

The Southern District of New York noted that Guvera failed to “allege… what ‘unconventional technological solution’ it provide[d] to a ‘technological problem.’”11

On appeal before the Federal Circuit, Guvera interestingly declared in its opening brief that its patent “solves a marketing problem.”12 Spotify, in its response brief, seized on the opportunity to point out “Guvera even concedes that its alleged invention is intended to ‘solve[] a marketing problem’ rather than a technological one.”13

The Federal Circuit affirmed the decision of the Southern District of New York under Federal Circuit Rule 36 without opinion.14

It is important to note that Guvera’s patent was filed with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) on December 15, 2010, almost four years before the Alice decision on June 19, 2014.

Furthermore, a notice of allowance was issued in the application on November 5, 2014, before the first USPTO subject-matter-eligibility guidance examples, 1-36, were published on December 16, 2014.

Thus, Guvera’s patent application could not have been drafted with the benefit of the case law and USPTO administrative guidance that followed.

The USPTO published subject-matter-eligibility guidance examples 37-46 in 2019 and published examples 47-49 in 2024.

The guidance was updated in 2019 to: (i) provide a two-prong inquiry under step one of the Alice two-step test—for determining whether additional claim elements integrate a judicial exception (e.g., an abstract idea) into a practical application—and (ii) provide explicit subcategories of abstract ideas (e.g., mathematical concepts, methods of organizing human activity, and mental processes).15

The guidance was updated in 2024 to assist with determining eligibility of claims involving artificial intelligence-related technology.16

The USPTO guidance examples can be useful for understanding differences between example eligible claims and example ineligible claims to the same subject matter.

How could Guvera’s patent application have been written differently to avoid a determination of invalidity under Section 101?

One of the more reliable ways to overcome a challenge under Section 101 is to show that some of the features in the patent claims provide an improvement to computer functionality. Under Section-101 case law, patent claims that are directed to an improvement to computer functionality are not directed to an abstract idea and are, therefore, patent eligible.17

One of the more reliable ways to show that features in the patent claims provide an improvement to computer functionality is to describe those features, in the detailed description of the patent application, within a technological problem-solution framework.

One way to determine whether a technological problem-solution framework has been provided for a feature is to ask whether the patent application explains how that feature makes the computer (i.e., the device on which the software feature runs) operate more efficiently than with other approaches.

For example, software instructions are typically executed using some type of hardware processor and memory. In many cases, some portion of the detailed description can be drafted to emphasize how the processor and the memory operate more efficiently as a result of some of the claimed features.

Guvera was unable to show that its claimed approach provided an improvement to computer functionality because its patent did not include a clear technological problem-solution statement.18

Therefore, Guvera’s patent provides insight into when a software patent might be in danger of being invalidated under Section 101.

In summation, when determining whether a software invention is eligible for patent protection, try to think of the idea in terms of how it improves computer functionality in a way that is different from other approaches.

1 See, e.g., Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank Int’l, 573 U.S. 208 (2014) (setting forth a two-step test for patent subject-matter eligibility that turned the software-patent world upside down).2 Guvera IP Pty Ltd. v. Spotify, Inc., No. 21-CV-4544 (JMF), 2022 WL 4537999 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 28, 2022); Guvera IP Pty Ltd. v. Spotify USA Inc., No. 2023-1493, 2024 WL 1433505 (Fed. Cir. Apr. 3, 2024).3 Guvera v. Spotify, 2022 WL 4537999, at *1.4 See U.S. Patent No. 8,977,633 (filed Dec. 15, 2010).5 Alice, 573 U.S. 208 (2014).6 See, e.g., Enfish, LLC v. Microsoft Corp., 822 F.3d 1327, 1335 (Fed. Cir. 2016); BASCOM Glob. Internet Servs., v. AT&T Mobility LLC, 827 F.3d 1341, 1349 (Fed. Cir. 2016).7 See, e.g., Alice, 573 U.S. at 223.8 Guvera v. Spotify, 2022 WL 4537999, at *7.9 Id. at *4.10 Id. at *7.11 Id. (emphasis added).12 Opening Brief of Appellant Guvera IP Pty Ltd. at 4, Guvera v. Spotify, 2024 WL 1433505, (No. 10) (emphasis added).13 Spotify USA, Inc.’s Response Brief at 2, Guvera v. Spotify, 2024 WL 1433505, (No. 13) (emphasis added).14 Judgment at 1, Guvera v. Spotify, 2024 WL 1433505, (No. 27).15 See, e.g., USPTO, Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on the 2019 Revised Patent Subject Matter Eligibility Guidance (“2019 PEG”), 2 (2019), https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/faqs_on_2019peg_20190107.pdf.16 2024 Guidance Update on Patent Subject Matter Eligibility, Including on Artificial Intelligence, 89 Fed. Reg. 58,128 (July 17, 2024).17 Enfish, 822 F.3d at 1335 (explaining that it is “relevant to ask whether the claims are directed to an improvement to computer functionality versus being directed to an abstract idea… for which computers are invoked merely as a tool”).18 See Guvera v. Spotify, 2022 WL 4537999, at *7.

States Shifting Focus on AI and Automated Decision-Making

Since January, the federal government has moved away from comprehensive legislation on artificial intelligence (AI) and adopted a more muted approach to federal privacy legislation (as compared to 2024’s tabled federal legislation). Meanwhile, state legislatures forge ahead – albeit more cautiously than in preceding years.

As we previously reported, the Colorado AI Act (COAIA) is set to go into effect on February 1, 2026. In signing the COAIA into law last year, Colorado Governor Jared Polis (D) issued a letter urging Congress to develop a “cohesive” national approach to AI regulation preempting the growing patchwork of state laws. In the letter, Governor Polis noted his concern that the COAIA’s complex regulatory regime may drive technology innovators away from Colorado. Eight months later, the Trump Administration announced its deregulatory approach to AI regulation making federal AI legislation unlikely. At that time, the Trump Administration seemed to consider existing laws – such as Title VI and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act and the Americans with Disabilities Act which prohibit unlawful discrimination – as sufficient to protect against AI harms. Three months later, a March 28th Memorandum issued by the federal Office of Management and Budget directs federal agencies to implement risk management programs designed for “managing risks from the use of AI, especially for safety-impacting and rights impacting AI.”

On April 28, two of the COAIA’s original sponsors, Senator Robert Rodriguz (D) and Representative Brianna Titone (D) introduced a set of amendments in the form of SB 25-318 (AIA Amendment). While the AIA Amendment seems targeted to address the concerns of Governor Polis, with the legislative session ending May 7, the Colorado legislature has only a few days left to act.

If the AIA Amendment passes and is approved by Governor Polis, the COAIA would be modified as follows:

The definition of “algorithmic discrimination” would be narrowed to mean only use of an AI system that results in violation of federal or Colorado’s state or local anti-discrimination laws.

The current definition is much broader – prohibiting any condition in which use of an AI system results in “unlawful differential treatment or impact that disfavors an individual or group of individuals on the basis of their actual or perceived age, color, disability, ethnicity, genetic information, limited proficiency in the English language, national origin, race, religion, reproductive health, sex, veteran status, or other classification protected under the laws of this state or federal law.” (Colo. Rev. Stat. § 6-1-1701(1).)

Obligations on developers, deployers and vendors that modify high-risk AI systems would be materially lessened.

An exception for a developer of an AI system offered with “open model weights” (i.e., placed in the public domain along with specified documentation), as long as the developer takes certain technical and administrative steps to prevent the AI system from making, or being a substantial factor in making, consequential decisions.

The duty of care imposed on a developer or deployer to use reasonable care to protect consumers from any known or foreseeable risks of algorithmic discrimination of a high-risk AI System would be removed.

This is a significant change from the focus on procedural risk reduction duties and away from a general duty to avoid harm.

Developer reporting obligations would be reduced.

Deployer risk assessment record-keeping obligations would be removed.

A deployer’s notice (transparency) requirements for a consumer who is subject to an adverse consequential decision from use of a high-risk AI system would be combined into a single notice.

An additional affirmative defense for violations that are “inadvertent”, affect fewer than 100,000 consumers and are not the result of negligence on the part of the developer, deployer or other party asserting the defense would be added

Effective dates would be extended to January 1, 2027, with some obligations pushed back to April 1, 2028, for a business employing fewer than 250 employees, and April 1, 2029, for a business employing fewer than 100 employees.

Even if the AIA Amendment is passed, COAIA will remain the most comprehensive U.S. law regulating commercial AI development and deployment. Nonetheless, the proposed AIA Amendment is one example of how the innovate-not-regulate mindset of the Trump Administration may be starting to filter down to state legislatures.

Another example: in March, Virginia Governor Glenn Yougkin (R) vetoed HB 2094, the High-Risk Artificial Intelligence Developer and Deployer Act, which was based on the COAIA, and a model bill developed by the Multistate AI Policymaker Working Group (MAP-WG), a coalition of lawmakers from 45 states. In a statement explaining his veto, Governo Youking noted that “HB 2094’s rigid framework fails to account for the rapidly evolving and fast-moving nature of the AI industry and puts an especially onerous burden on smaller firms and startups that lack large legal compliance departments.” Last year California Governor Gavin Newsom (D) vetoed SB 1047, which would have focused only on large-scale AI models, calling on the legislature to further explore comprehensive legislation and states that “[a] California-only approach may well be warranted – especially absent federal action by Congress.”

Meanwhile, on April 23, California Governor Newson warned the California Privacy Protection Agency (CPPA) (the administration agency that enforces the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA)) to reconsider its draft automated decision-making technology (“ADMT”) regulations to leave AI regulation to the legislature to consider. His letter echoes a letter from the California Legislature, chiding the CPPA for its lack of the authority “to regulate any AI (generative or otherwise) under Proposition 24 or any other body of law.” At its May 1st meeting, the CPPA Board considered and approved staff’s proposed changes to the ADMT draft regulations, which include deleting the definitions and mentions of “artificial intelligence” and “deep fakes.” The revised ADMT draft regulations also include these revisions (along others):

Deleting the definition “extensive profiling” (monitoring employees, students or publicly available spaces or use for behavioral advertising) and shifting focusing on use to make a significant decision about consumers. Reducing regulation of ADMT training. However, risk assessments would still be required for profiling based on systemic observation and training of ADMT to make significant decisions or to verify identity or for biological or physical profiling.

Streamlining the definition of ADMT to “mean any technology that processes personal information and uses computation to replace … or substantially replace human decision-making [which] means a business uses the technology output to make a decision without human involvement.”

Streamlining the definition significant decisions to remove decisions regarding “access to,” and limited to “provision or denial of” the following more narrow types of goods and services: “financial or lending services, housing, education enrollment or opportunities, employment or independent contracting opportunities or compensation, or healthcare services,” and clarifying that use for advertising is not a significant decision.

Deleting the obligation to conduct specific risk of error and discrimination evaluations for physical or biological identification or profiling, but the general risk assessment obligations were largely kept.

Pre-use notice obligations were streamlined.

Opt-out rights were limited to uses to make a significant decision.

Giving businesses until January 1, 2027, to comply with the ADMT regulations.

(A more detailed analysis of the CCPA’s rule making, including regulation unrelated to ADMT, will be posted soon.)

MAP-WG inspired bills also are under consideration by several other states, including California. Comprehensive AI legislation proposed in Texas, known as the Texas Responsible AI Governance Act, was recently substantially revised (HB 149) to shift the focus from commercial to government implementation of AI systems. (The Texas legislature has until June 2 to consider the reworked bill.) Other states have more narrowly tailored laws focused on Generative AI – such as the Utah Artificial Intelligence Policy Act which requires any business or individual that “uses, prompts, or otherwise causes [GenAI] to interact with a person” to “clearly and conspicuously disclose” that the person is interacting with GenAI (not a human) “if asked or prompted by the person” and, for persons in “regulated occupations” (generally, need a state license or certification), disclosure must “prominently” disclose that a consumer is interacting with generative AI in the provision of the regulated services.

What happens next in the state legislatures and how Congress may react is yet to be seen. Privacy World will keep you updated.

Ninth Upends Internet Personal Jurisdiction Law–Briskin v. Shopify

In a landmark ruling, the Ninth Circuit expanded the application of specific personal jurisdiction principles to the realm of nationwide e-commerce. On April 21, 2025, an en banc panel issued a 10–1 decision ruling that allegations that Shopify embedded cookies that tracked a California consumer’s location data were sufficient to establish specific personal jurisdiction over Shopify in California (reversing the Court’s prior opinion on this exact issue). In the wake of this decision, businesses may face increased legal challenges in various states. To protect against far-flung lawsuits in unwanted jurisdictions, e-commerce businesses should, if practicable, refrain from collecting location data and engaging in other online activities that may be seen as targeting consumers of a particular state.

The case—Brandon Briskin v. Shopify, Inc.—involves Brandon Briskin, a California resident, who accused Shopify, Inc., a Canadian corporation, along with its U.S. subsidiaries, of privacy violations during an online transaction. Briskin alleged that Shopify unlawfully collected and used his personal information, including location data, without consent, focusing on Spotify allegedly installing tracking cookies and creating consumer profiles from collected data. The district court dismissed the case for lack of specific personal jurisdiction, ruling that an e-commerce platform such as Shopify, which operates nationwide, does not specifically target California residents. The Ninth Circuit affirmed the district court’s ruling but later agreed to reconsider the personal jurisdiction determination en banc.

Applying traditional personal jurisdiction principles to Shopify’s e-commerce activities, the Ninth Circuit panel held that because Shopify’s geolocation technology allowed it to know where Briskin’s smartphone was located in California when it installed cookies on his device, Shopify’s conduct of intercepting Briskin’s information deliberately targeted a California resident, meeting the purposeful direction requirement for specific personal jurisdiction. Accordingly, per the Ninth Circuit, an interactive platform “expressly aims” its wrongful conduct toward a forum state when its contacts are its “own choice and not ‘random, isolated, or fortuitous,’” even if that platform cultivates a “nationwide audience[] for commercial gain.

A significant aspect of the decision was the panel’s rejection of the necessity for “differential targeting,” which refers to the concept that a defendant’s actions within a forum state create specific personal jurisdiction only if the defendant acted with “some prioritization of the forum state”—rather than a general, nationwide focus. This ruling indicates that a business model like Shopify’s, which operates nationwide and utilizes consumer data, can be subject to jurisdiction in any state where it (1) gathers data from a resident of such state and (2) the business has some indication of the resident’s physical location when interacting with the business.

Judge Callahan dissented, expressing concerns that Shopify’s conduct was not expressly aimed at California. The dissent cautioned that the majority’s approach could lead to companies facing jurisdiction based solely on the plaintiff’s location during transactions and noted “[b]y holding that California courts can exert specific jurisdiction over Shopify because Briskin used his iPhone while ‘located in California,’ […] the majority opinion departs from the longstanding principle that jurisdiction turns on ‘the defendant’s contacts with the forum State itself, not the defendant’s contacts with persons who reside there.’”

Putting it Into Practice: The Ninth Circuit’s decision is a major sea change to personal jurisdiction of businesses in the digital age, particularly e-commerce businesses. This ruling serves as a reminder for e-commerce platforms to consider their interactions with consumers in various states, as their business activities may subject them to jurisdictions across the map. To lessen the impact of the Shopify ruling and the likelihood of personal jurisdiction being established in states in the Ninth Circuit businesses can consider geofencing, refraining from collecting online location data, and making sure that other aspects of the business’s online activities are not purposefully directed at a particular state.

Listen to this article

State Department Updates DS-160 Submission Rules

The U.S. Department of State has recently updated its procedural guidelines for visa applicants, introducing a new requirement that may impact how travelers plan their application process. The DS-160, the mandatory Online Nonimmigrant Visa Application, must now be submitted at least 48 working hours before an interview at a U.S. embassy or consulate is scheduled. This change, although seemingly minor, has implications that applicants should consider as they navigate the often complex visa process.

What Is the DS-160?

The DS-160 is a comprehensive electronic State Department form that collects personal, travel, and employment information from applicants seeking a U.S. visa. Completing this document and submitting it online is the first required step in the nonimmigrant visa application process. After submission, applicants receive a confirmation page with a barcode, which is essential for scheduling a visa interview.

What’s Changing — and Why It Matters

Previously, applicants were able to schedule interview appointments promptly after submitting their DS-160 forms. However, under the new rules, the State Department requires at least 48 working hours between the time the DS-160 is submitted and the scheduling of the visa interview. This change may have been implemented to streamline internal processing and allow embassies and consulates sufficient time to review the submitted information before applicants schedule interviews.

Key Points to Know:

48 Working Hours: It’s important to note that this timeframe refers to business days, which excludes weekends and U.S. federal holidays. For example, if an applicant submits the DS-160 on a Friday afternoon, the earliest they could potentially schedule an interview would be the following Tuesday.

Planning Is Crucial: This adjustment underscores the importance of proactive planning. Visa applicants should not only complete their DS-160 but also consider building in extra time to account for the processing window as well as the availability of interview appointments at their preferred embassy or consulate.

No Exceptions: The State Department emphasizes that this requirement is firm, so rushing or attempting to bypass the 48-hour rule is not advisable. Missing this mandate may cause delays in scheduling interviews or receiving visas, which may affect applicants’ overall travel timeline.

Considerations for Applicants:

Submit DS-160 Early: Considering this new requirement, applicants may wish to complete and submit the DS-160 long before thinking about scheduling an interview. Planning ahead may help ensure a smooth progress through the application process.

Coordinate Forms and Fees: Be sure that all components of your application—such as paying the visa fee—align with the DS-160 submission timing. Interviews cannot be scheduled unless all prerequisites, including this submission window, are satisfied.

Monitor Embassy Availability: Some U.S. embassies and consulates have longer waiting periods for interview slots due to high demand. Applicants should look up the interview appointment availability at their local missions to better strategize when to submit the DS-160.

Why the Rule Might Be Beneficial

Although this new policy introduces an additional layer of waiting time, it might yield improved outcomes for applicants. By allowing embassies and consulates a buffer to review submitted forms, officials can catch errors or inconsistencies ahead of the interview.

Takeaways

While the new 48-hour DS-160 submission rule may require adjustments to travel plans or visa preparation timeline, it’s not insurmountable. With foresight, organization, and careful planning, applicants can comply with the requirement and ensure their visa process flows smoothly. Every step in the visa application sequence exists to promote clarity and efficiency, and understanding these changes may help avoid last-minute frustrations. For those seeking to visit the United States, staying informed of procedural updates like this demonstrates the importance of being detail-oriented and proactive.

United States: The Continuing Shift to Modern Money Transmission Laws

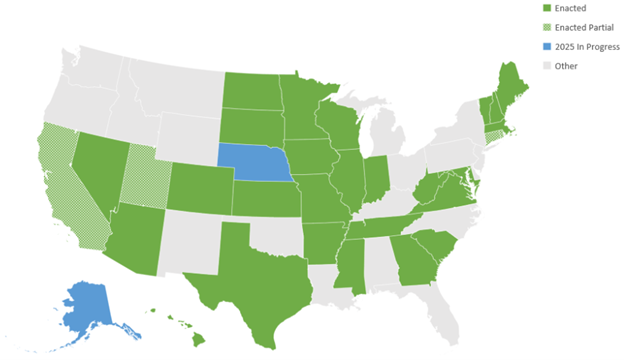

Within the past two months, three states have adopted the Money Transmission Modernization Act (MTMA). The governors of Virginia, Mississippi, and most recently Colorado, signed bills that implement the MTMA, and two other states are currently considering similar bills (Alaska and Nebraska).

Mobile wallets, peer-to-peer payments, and digital assets are modern methods of moving money, but have been historically regulated by laws that in some states have been around for over one hundred years. These laws were originally designed for older forms of non-bank payments, such as money orders, Western Union style remittance services, and travelers checks. The recent boom in financial technology has enabled fintechs to provide nationwide and instant payments, which heightens the need for more uniform laws governing non-bank money transmission. To keep up with the pace of financial technology, the Conference of State Bank Supervisors created the MTMA to bring state money transmission laws into the 21st century. To date, more than half of the states have enacted at least part of the model law. As the rest of the country continues to converge on the MTMA’s model

provisions, money transmission licensing for non-banks will grow more streamlined, enabling more efficient compliance, and thus more efficient payments.

Source: Conference of State Bank Supervisors, CSBS Money Transmission Modernization Act (MTMA) (updated Apr. 30, 2025 ), https://www.csbs.org/csbs-money-transmission-modernization-act-mtma.

The three recent states’ bills enacting the MTMA will go into effect over the next year: Mississippi HB1428 (effective 7/1/2025); Colorado HB1201 (expected to be effective around 8/6/2025); and Virginia HB1942 (effective 7/1/2026). Interestingly, all of these new laws omitted one provision from the model act. Each bill excluded the optional “virtual currency” provisions of the MTMA, which would have explicitly treated certain virtual currency activity as money transmission. Moreover, Virginia also excluded “virtual currency” from the definition of money, indicating a legislative intent to exempt virtual currency from the law. These differences demonstrate that, despite the MTMA efforts to bring general uniformity in state laws, nuances among the states still exist.

Breaking Down the First Legislative Compromise on Commercial Litigation Funding

On April 8, Kansas Senate Bill No. 54 (SB54) became law. SB54 is the first-ever legislative compromise between the commercial legal finance industry and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce (the “Chamber”). The law represents a sensible balance between legitimate regulatory goals, such as identifying conflicts of interest, while protecting privileged and confidential information from the prejudice associated with overbroad, forced disclosure. SB54 has elements in common with other approaches to limited disclosure, such as Judge Polster’s procedures in the Opioids MDL, the 2023 recommendations of the Delaware Judiciary, and District of New Jersey Local Civil Rule 7.1.1.

I negotiated the language of SB54 on behalf of the International Legal Finance Association (“ILFA”). Representatives of the Chamber and the Kansas Chamber of Commerce participated directly in the negotiation of the compromise, which was aided by members of the Senate Judiciary Committee. This article provides an overview of what SB54 does—and does not—require, and why.

Disclosure

SB54 requires the automatic production of commercial litigation funding agreements to the court in camera, with limited disclosures made to opposing parties.

Prior to the negotiation, the Chamber had insisted upon automatic production of full funding agreements to parties. ILFA opposed this provision—as it does consistently—on the grounds that funding agreements: (1) contain sensitive work product, (2) have been held by a “chorus of courts” to be irrelevant and/or protected from disclosure, and (3) contain information that may be used by opposing parties for inappropriate strategic advantage.

As a result of our negotiation, the Chamber softened its previous position that opposing parties in litigation should have the right to automatically obtain funding agreements. Instead, the Chamber agreed to the following limited disclosures regarding the funding agreements, which can be verified by the court’s in camera review.:

The funder’s identity and place of incorporation;

Whether a funder has control or approval rights for litigation decisions;

Whether a funder has the right to review materials designated confidential under a protective order;

Known conflicts between a funder and the adverse party, its counsel, or the court;

A description of the nature of the funder’s financial interest; and

Whether the funder has capital from adverse foreign countries.

These representations address various arguments—many of which, to be clear, are purely hypothetical—that the Chamber has asserted in its effort to advance broader proposals that would mandate prejudicial forced disclosure of full funding agreements under the guise of transparency. For example, the Chamber has argued for full disclosure because “everyone involved in a lawsuit should know who is funding it” and “to avoid conflicts of interest” with the judiciary. The Chamber has also argued for full disclosure on the basis that “funders can exercise immense control over litigations in which they invest,” and could be backed by adverse foreign interests that “may even seek to access confidential trade secret information for state purposes.” These unsupported concerns, as far-fetched and implausible as some of them may seem, are nevertheless addressed by SB54 in a tailored manner that does not afford defendants strategic advantage or lead to satellite litigation, while also providing appropriate levels of transparency and protecting the court’s inherent authority to manage its cases.

Scope

SB54 only requires disclosure regarding agreements between funders and parties. It does not require disclosure concerning financing agreements between funders and counsel, as funders are not in contractual privity with parties under such arrangements. Accordingly, SB54 only requires representations about agreements “if a party has entered into a third-party litigation funding agreement,” which is logical in light of the fact that lawyer-directed financing does not implicate the lion’s share of concerns articulated by the Chamber due to the lack of privity. In addition, disclosure of law firm financing would necessarily ensnare more traditional financing arrangements, such as recourse lines of credit provided by financial institutions.

Foreign Capital

SB54 requires disclosure of capital from “foreign countries of concern,” i.e., those federally designated as foreign adversaries or terrorist organizations, consistent with the approach taken in other states such as Louisiana. ILFA has no objection to this provision, notwithstanding that the Chamber’s articulated bases for seeking such disclosure—that hostile foreign powers may use litigation financers as a conduit to finance cases that are contrary to the U.S. national interest or as a means of obtaining sensitive material produced in discovery—are baseless. Legal finance firms do not control the matters in which they invest. Nor do funders have access to sensitive documents and information produced in discovery. Such information, such as trade secrets, are already protected from improper disclosure through strict protective orders. Investors in legal finance firms are even further attenuated from underlying litigation. They generally have no role in the selection of investments, much less the materials produced via discovery. As one legal expert recently said, the speculation regarding national security is “evidence-free,” and requires “conspiracy thinking to believe this would or could happen.”

The Chamber’s initial bill language required disclosure of capital from all foreign entities, which would have unnecessarily reduced litigants’ access to capital because a significant share of the funding market has been historically domiciled in foreign, allied countries. The Chamber agreed to this compromise, and ILFA accepted the Chamber’s definition of “foreign country of concern.”

Other Provisions

Notably, SB54 does not contain a number of other problematic provisions that are present in disclosure bills proposed in other states, many of which would operate as de facto funding prohibitions. Examples include indemnification for adverse costs, registration, discovery concerning funding and admissibility of funding-related information, mandatory contract language, and return limitations.

Outlook

SB54 demonstrates that compromise is attainable in the historically polarized litigation funding disclosure debate. For states considering pending legislation—many of which face fatigue from perennial bills that seek to solve nonexistent problems—precedent now exists for a rational level of disclosure that protects against prejudice and preserves access to justice.

Dai Wai Chin Feman is a managing director at Parabellum Capital, where he oversees commercial litigation investments and public policy.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The National Law Review.

National Computer Virus Center of China Identifies Violations of Cross-border Transfer Requirements

The National Computer Virus Emergency Response Center of China (“NCERT”) recently discovered 2 mobile apps in breach of cross-border transfer requirements in accordance with the Cybersecurity Law, the Personal Information Protection Law, the Method for Determining the Acts of Illegal, the Illegal Collection and Use of Personal Information by Apps, and other relevant laws and regulations of China.

This was the first time that NCERT announced non-compliance activities related to cross-border transfers of personal information. The non-compliance included the failure to inform relevant data subjects of the contact information of the overseas recipient, the purposes and means of processing by the overseas recipient, the types of personal information transferred to the overseas recipient, and the methods and procedures the data subjects may use to exercise their rights against the overseas recipients, and the failure to obtain separate consent.

FAIR WARNING: GEICO Facing Revised Class Certification Effort in TCPA Suit Over Unwanted Robocalls

One of the most frustrating parts of defending class litigation is when a court allows a party to re-define their class at the time they seek certification.

If you pause to think about that it is absolutely wild.

A defendant might litigate a case for 18 months focused on one class definition, go through discovery, complete expert reports and then have the plaintiff completely change course with virtually no warning.

Terribly unfair and inconsistent with due process in my view.

Better practice is for a plaintiff to give the defense fair warning of their true intentions at the pleadings stage–which is why a motion to strike overly broad classes makes so much sense and Troutman Amin, LLP leverages such motions frequently.

But in an unusual case GEICO and ExamWorks, LLC are sued in a TCPA class action with a plaintiff who is voluntarily seeking to amend his class. And interestingly GEICO opposed the amendment effort.

In Michael Smith v. ExamWorks, 2025 WL 1262931 (D. Md. May 1, 2025) the Plaintiff suing for unwanted robocalls allegedly made by ExamWorks on behalf of GEICO.

The current class definition is: “all persons in the United States” who: (1) were called with a pre-recorded voice message by ExamWorks (or any party on behalf of ExamWorks); (2) to their cellular telephone provided to ExamWorks by GEICO; (3) during the four-year period prior to filing the complaint in this action through the date of certification; and (4) where the called party did not provide the cellular number called to either GEICO or ExamWorks.

The Plaintiff sought to amend the class definition to remove the reference to GEICO in the final sentence of the definition. Thus it would read: “where the called party did not provide the cellular number called to ExamWorks.”

Now in my view, this was a pretty classy move by the Plaintiff. They are giving the defense notice of a planned change before filing for certification and really pinning themselves down to a new definition so the defendants don’t need to worry about another late-stage change. Plus, in my view the newly-defined class is actually harder to certify than the original class. So I would have taken this amendment with a thank you.

But GEICO and ExamWorks both decided to oppose the amendment on a bunch of grounds. Their arguments are pretty weak and basically boil down to “the class can’t be certified and is not fair that they’re changing their definition” to which the court responded (properly) that it is too early to determine class certification, on the one hand, and not too late to change a definition, on the other.

The Court noted in particular that Plaintiffs’ effort to amend was classy and “seems to minimize surprise and unfair prejudice to Defendants.”

So yeah. Defendants objected to something they probably should have been grateful for. If only all TCPA defendants were so lucky.