5 Ways Estate Attorneys Can Bring Order to Their Clients’ Digital Asset Chaos

Digital assets are exploding. According to NordPass, the average person now has 168 online accounts, and that list is growing all the time — in both volume and value. A new survey from Bryn Mawr Trust found that Americans estimate an average value of $191,516 in digital assets; yet, 76% of them still have little to scant knowledge of digital estate planning. More problematic, many advisors still do not acknowledge digital assets as a general asset category to address with clients. As a result, many estate plans inadequately address — or completely ignore — access to and the disposition of digital assets.

Digital assets, at a high level, include: digitally stored documents, email accounts and electronic communications, loyalty program rewards and airline miles, photos and videos, social media accounts, cryptocurrency, subscriptions, online businesses, other digital interests, and accounts controlled by service providers. They all now demand proper estate planning.

Why does any of this matter? Overlooking digital assets leaves the legal representatives of the estate (i.e. executor, administrator, and personal representative):

Potentially locked out of valuable digital assets and accounts, resulting in a direct financial or sentimental loss to the estate and its beneficiaries.

Spending countless hours and resources trying to gain access to said accounts.

Dealing with exposed personal identifiable information from the decedent’s various online accounts, leaving them vulnerable to identity theft and other cybersecurity risks.

In addition to failing to comprehensively serve evolving client needs, a lack of planning in this area could expose attorneys and other advisors to potential future liability. How to access and transfer digital assets should be a standard part of every client conversation for the modern estate planning advisor.

Digital assets are more ubiquitous and valuable than ever, so why does a large swath of the estate planning community still lag behind in addressing this critical area?

This generally stems from a lack of understanding of:

The prevalence of digital assets in most clients’ lives;

The potential negative impact if these assets are overlooked;

How to address this topic with clients;

How to effectively incorporate digital interests into estate plans and accompanying materials; and

Where to turn to for technical guidance and support.

The following general guidelines are aimed to help estate planning advisors better understand this developing area and begin to guide clients through the digital estate planning process, in order to protect clients, their legal representatives and beneficiaries, and our practices:

1. Educate Clients on the Importance of Digital Asset Planning

Most clients don’t realize the risks of ignoring their digital behaviors and footprint. In fact, you have probably heard some say:”I don’t have any digital assets.”

Further, many advisors and clients operate under the ill-advised assumption that, if they don’t own any cryptocurrency, then they don’t have any digital assets. However, the reality is the majority of people have a plethora of digital assets and accounts. Whether they realize it or not, our clients are creating digital footprints in a multitude of ways, every day, often without a second thought. As technology progresses, our digital and physical lives are reaching new levels of entanglement.

So, if a client has, at a minimum:

Photos or videos on a device or in a cloud

Email accounts (and other online electronic communications, Slack, Google Chat, WhatsApp, etc.)

Social media profiles

Online banking, utility, or shopping accounts

Cloud storage (Google Drive, iCloud, etc.)

Loyalty programs or airline miles

…they are accumulating digital assets, accounts, and interests that require protection and planning.

Many clients may also now have an interest in or accumulate:

Domain names and websites

Digital works, recordings, and content (artists and creators)

Ecommerce and other online businesses (i.e. Etsy, Amazon, etc.)

Cryptocurrency, NFTs, and Forex

Gaming tokens

Metaverse or other virtual property

Avatars, digital twins, and personalized bots (and customized AI large language models)

Name, image, and likeness (NIL) considerations, where applicable

… which require even more protection and planning.

The diverse categories of digital assets above demonstrate why it’s important to ask clients questions about their digital behaviors as part of the standard estate planning conversation. Here are a few examples of questions to help initiate the digital asset planning discussion:

Do you use online bill pay for any of your recurring expenses?

Who handles this in your household?

How many personal email accounts do you use?

How much shopping do you do online?

What are your three most important digital assets?

How do you store photos and videos?

Do you use social media?

What, if any, important information do you still receive through traditional mail?

If something suddenly happened to you, is there information in cyberspace or data in a device that would need to be accessed to help administer your estate or that you would want to be transferred to a certain individual or deleted?

These questions are just the beginning of the conversation and can provide a wealth of information to direct the structure of the digital asset aspect of the plan, which should be based on the needs and desires of the client.

2. Help Clients Inventory Their Digital Assets

Most clients underestimate the size of their digital footprint. Beyond social media and email, they often have a mix of valuable, sentimental, and potentially vulnerable digital accounts with personally identifiable information that need managing. As part of gathering general asset and liability information for a client at the beginning of the planning process, collecting information regarding digital assets, accounts, and devices and understanding digital behavior should be standard practice.

There are online services to help you handle this, but here are some tips if you want to do-it-yourself:

Start with Hardware

An inventory should have an area for clients to list all devices that store data, access online accounts, or store biometric information:

Computers & Laptops

Smartphones & Tablets

External Drives, Flash Drives & Hard Wallets

E-Readers, Digital Cameras & Music Players

Wearables, Smart Glasses & Gaming Devices

Alarms & Smart Home Systems

Tip: Even old devices may store sensitive data that requires attention and protection.

Include Stored Data

The inventory should go beyond hardware and map out where digital files reside:

Cloud Services: Google Drive, iCloud, Dropbox, etc.

Local Drives & External Storage: Hard drives, SD cards, USBs

Backups & Archives: Time Machine, Windows Backup

AWS Drives and Services

Applications

Many clients and advisors overlook the personal and financial data tucked away in the cloud, applications, or on forgotten drives. Where is that manuscript? Where are all the family photos and videos stored?

List Online Accounts & Digital Assets with Monetary or Sentimental Value

The inventory should also include all online accounts and digital assets with monetary or sentimental value, as this is where assets can be overlooked, which could result in financial or other loss. Encourage clients to list:

Email Accounts: The gateway to most digital assets and accounts in a paperless world.

Social Media: Facebook, LinkedIn, Instagram, etc.

Financial Platforms: Banks, PayPal, Venmo, Wallets/Exchanges

E-Commerce & Subscriptions: Amazon, streaming services, food delivery

Utilities & Loyalty Programs: Household bills, airline miles, hotel points

Cryptocurrency (date acquired, purchase price, type, blockchain, method stored, public exchange/self-custody? If self-custody, how held [hot storage/cold storage]? How are keys/recovery seed phrases stored?)

NFTs (date acquired, price, blockchain, internet location, transfer rights, royalties, etc.?)

Pro Tip: Have them scan emails for receipts and password reset links to uncover forgotten accounts.

Flag Web-Based Assets & Intellectual Property

For entrepreneurs, creators, or side hustlers, dig deeper:

Domain Names & Hosting Accounts

Websites, Blogs & Online Stores (Shopify, Etsy, and Amazon)

Creative Works: Copyrighted materials, trademarks, code, art, photography, etc.

Having an inventory of the digital assets and accounts of a client stored in a safe location will save significant time and expense in the future. It is also important to periodically update the inventory as digital interests change and expand. Sharing this type of information is prohibited under several federal laws, such as the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act and the Stored Communications Act.

3. Help Clients Set Wishes For Each Asset

Not all digital assets and accounts should be treated equally. Digital asset planning cannot be done using a one-size-fits-all approach. Digital assets and behaviors can vary widely among clients, much like general planning needs for traditional assets.

For instance, some clients will want to preserve family photos or social media accounts, while others may want certain accounts deleted for privacy. It’s important to note: even if digital assets and accounts can be legally accessed by an estate representative, legal access does not equate to actual use, and oftentimes, additional pre-planning measures are required to provide instructions on how to use digital assets or what to do with them once accessed (i.e. an Etsy shop or small online business with intellectual property). This type of use information is not customarily included in the legal documents in an estate plan and instead should be provided through instructions manuals, a tech management plan, or other user related information as part of the overall planning process.

Others clients still may want to liquidate and transfer crypto assets to their estate representatives, which can require additional technological expertise and assistance, and the timing of this can also have potential tax and valuation implications. Cryptocurrency poses its own set of unique planning challenges, which can vary depending on the type of crypto and how it is held (i.e. public exchange or self-custody [which can also take on various forms]) and planning for this type of interest will be further addressed in a future article.

It is important to discuss the following considerations with clients:

Access/Transfer

Can the digital asset be legally transferred or does the user only have a lifetime license?

Can the digital asset be legally owned or accessed by a trust?

Are there revenue-generating accounts, cryptocurrency wallets, or loyalty points that should be preserved or transferred to the estate?

Should online businesses or websites be transferred to a successor or closed and how are these activities being supported during transitional periods?

What information is going to need to be immediately accessible to legal representatives in the event of sudden incapacity or death?

Preserve

Should sentimental assets like family photos, records, videos, or social media profiles be archived for future generations? Who should be the recipient(s)? Should these digital memories be saved in other formats to ensure ease of access?

Is there any intellectual property, like creative works or digital art, that need to be preserved?

Are there recurring subscription fees for software, programs, or platforms connected to or necessary to use/access the digital interest?

Is the digital asset or interest located online or contained in a computer, device, or hard drive? How are items of tangible property that can have intangible digital components handled in an estate plan?

Close

Which accounts should be permanently closed or scrubbed to protect privacy, such as unused subscriptions, wearables, or social media profiles?

Is there any sensitive data that should be wiped, like email accounts or online shopping accounts, or data on a device to prevent identity theft?

Be Aware of Online Tools & RUFADAA Compliance

As part of this conversation, clients must also understand the Revised Uniform Fiduciary Access to Digital Assets Act (RUFADAA), a law adopted by most states to regulate access by a fiduciary (i.e. executor, administrator or personal representative of an estate, trustee of a trust, agent under power of attorney, and guardian of an incapacitated person’s estate) to the digital assets and accounts of a user. Under RUFADAA, users must explicitly authorize fiduciary access based on a three-tier hierarchy:

An Online Tool (an agreement between the user and a service provider separate, which provides directions for the disclosure or non-disclosure of digital assets)

Estate planning documents that address fiduciary access (if an Online Tool is not available or used); and

Terms of Service Agreements (TOSAs) apply if neither of the first two exist. However, many TOSAs restrict or prohibit asset transfers or are silent on fiduciary access, often requiring a court order for access in many situations.

Even if fiduciary access provisions are incorporated into an estate plan, some service providers may still require a court order authorizing access before it is provided or may limit access to certain information. For example, electronic communications, such as the contents of an email, are subject to a heightened standard of privacy under RUFADAA and access must be specifically authorized in estate planning documents or an Online Tool to be disclosed. Obtaining court orders to access digital accounts can be time consuming and expensive — increasing the importance of clear instructions and directives for digital assets to reduce delays and potential legal hurdles.

In addition, identifying accounts where Online Tools have been utilized is important to include in the digital asset inventory. The use of an Online Tool is similar to a beneficiary designation for traditional assets (i.e. retirement plans, investment accounts, and life insurance policies) without the well-settled law to invalidate designations in a variety of situations. Using Online Tools has many benefits and can streamline access, but should be done with great care and reviewed as part of an overall estate plan.

Additionally, new tech solutions have entered the marketplace to help advisors and clients manage digital estates and legacies. These platforms offer inventory tools, secure storage, and digital memorialization services. Such platforms can help reduce legal hurdles, ensure a secure and seamless transition of digital assets and important information, and better serve future estate representatives and practitioners as they carry out the client’s wishes.

4. Partner With Tech-Savvy Professionals & Advisors

The transfer and access of property, including digital assets (that are not controlled by an Online Tool or TOSA), is carried out through the estate administration process, and what a fiduciary is allowed or prohibited to do is determined by jurisdictional estate and fiduciary laws and the provisions of a will or revocable trust.

Unlike physical assets, which can often be easily identified and transferred, digital assets may be protected by passwords, encryption, and privacy policies. They could also have complicated technological components, making them difficult to access without the help of seasoned experts.

While some clients have more complicated technological needs, one solution to address this situation is to empower the fiduciary to be able to hire technology experts to assist with administration of the digital estate.

Another option is to appoint a technology advisor or committee in the planning documents for the fiduciary to utilize. Technical advisor appointments can define the scope of the advice to be provided, requisite technical expertise aligned with a specific digital asset, and include discretionary powers that can be modified by the fiduciary.

Lastly, estate advisors should be familiar with different types of advisors to serve their clients digital interests and needs. For example, some digital assets may be hard to value, requiring specialized expertise from qualified appraisers. Other clients may have their personal or business IT systems hacked, requiring referrals to competent cybersecurity teams and outfits.

5. Make It Legally Binding and Review Regularly

These are many types of clients with varying digital usage that impact both technical and legal aspects of an estate plan. A well-structured digital estate plan should be actionable, secure, and seamlessly integrated with an overall estate plan.

A basic estate plan typically includes:

A will

In some states, a revocable trust

Financial and healthcare powers of attorney

At a minimum, practitioners should discuss with their clients the laws governing fiduciary access to digital assets in their jurisdiction, and whether the client intends to provide for the access or deletion of their digital assets and accounts.

Best Practices for Drafting Digital Asset Provisions

The will should include a clear digital asset clause specifying the client’s intent regarding:

Fiduciary access to digital assets, electronic communications, and online accounts.

A definition of digital assets.

Revocable trusts and financial powers of attorney should echo these directives.

Wills and/or revocable trusts should designate beneficiaries for each digital asset.

Never list usernames or passwords directly in a will or trust. Instead, store this information in a secure location instead.

For clients with complex digital assets, additional documents may be necessary, such as:

Instruction manuals detailing access and management procedures.

Technology management plans to optimize access and use.

As discussed above, if Online Tools are used as part of the planning process, the designated recipient named in the Online Tool or the directive provided will trump fiduciary access provisions in a will or revocable trust.

Reviewing the overall plan on a regular basis helps ensure the plan remains current and provides an opportunity to realign the plan with life changes, new digital assets, and technology platforms designed to help clients and practitioners manage digital assets.

Estate Planners: the Time to Act is Now

Digital assets must no longer be treated as an “emerging” asset class. It’s 2025 — they’ve effectively emerged. For practitioners putting off digital asset planning, make no mistake: digital asset proliferation isn’t going anywhere. The need for this type of planning will only further spike and grow more complicated. Our clients have a digital life, and we must acknowledge that managing digital footprints, devices, accounts, and assets is non-negotiable for a comprehensive estate plan.

As trusted advisors, we must keep apprised of the legal and technical developments surrounding digital assets with the same diligence we apply to staying atop legislative and tax changes that may impact planning. There is too much at stake to ignore or take lightly this growing challenge. Doing so puts our clients at risk and exposes our practices to potential liability. Our clients expect us to secure their digital legacies with a modern approach to the planning process. They expect us to help them bring order to their digital chaos.

Now, it’s time we deliver.

Québec’s Restrictive Approach to Biometric Data Poses Challenges for Businesses Working on Security Projects

The recent decision by the Commission d’accès à l’information du Québec (CAI) regarding a popular grocer’s biometric data project in Quebec has far-reaching implications for other businesses considering or currently using biometric technologies. This pivotal decision not only highlights the CAI’s stringent approach to privacy protection but also sets a significant precedent for any company utilizing or considering utilizing biometric technologies in Quebec. Businesses will want to closely monitor developments to ensure compliance with Quebec’s privacy laws and adapt their practices accordingly.

Quick Hits

The CAI emphasized the broad interpretation of “identity” and “verification” under Quebec’s privacy laws.

The decision highlights the quasi-constitutional nature of privacy protection in Quebec.

The CAI emphasized that if consent involving the capture and comparison of biometric data for identification purposes cannot be obtained, a project—even one focused on security—may not be approved in Quebec.

A prominent grocery store in Quebec proposed implementing a biometric data bank for facial recognition to combat theft and fraud in its stores. The system aimed to identify individuals involved in shoplifting or fraud by comparing surveillance footage with a database of biometric data. However, the CAI’s investigation focused on the project’s compliance with Quebec’s privacy laws, specifically the Act respecting the protection of personal information in the private sector and the Act to establish a legal framework for information technology.

Distinction Between Verification and Identity

A critical aspect of the CAI’s decision was the broad interpretation of “identity” and “verification” under Quebec’s privacy laws. The CAI determined that the grocer’s facial recognition system constituted a form of identity verification, as it involved capturing and comparing biometric data to identify individuals. This interpretation means that any process involving the capture and comparison of biometric data for identification purposes requires explicit consent from the individuals concerned, as mandated by Article 44 of the Act to establish a legal framework for information technology.

The CAI rejected the grocer’s argument that their system did not constitute identity verification because it did not confirm the exact identity of every individual entering the store but rather identified those who matched the biometric profiles of known offenders. The CAI clarified that the act of identifying individuals based on biometric data, even if it is to determine if they belong to a specific group (e.g., known shoplifters), still falls under the category of identity verification.

Explicit Consent Requirement

The CAI highlighted that under Article 44 of the Act to establish a legal framework for information technology, any process that involves the verification of identity through the capture and comparison of biometric data requires the explicit consent of the individuals concerned. The CAI noted that the grocer’s project did not plan to obtain such explicit consent, thereby violating the legal requirements. This requirement for explicit consent is a critical point for other businesses to consider. Any business using biometric technologies may want to confirm that they obtained explicit consent from individuals before collecting and using their biometric data. Failure to do so could result in significant legal repercussions and potential prohibitions on the use of such technologies.

Quasi-Constitutional Nature of Privacy Protection

The CAI’s decision highlights the quasi-constitutional nature of privacy protection in Quebec. Privacy laws in Quebec are designed to offer robust protection to individuals, and the CAI has broad powers to enforce these laws. This means that businesses may want to be particularly diligent in their compliance efforts, as the CAI is likely to take a restrictive approach to the use of biometric data and other sensitive personal information.

Next Steps

The CAI’s decision on the grocer’s biometric data project has significant implications for other businesses using biometric technologies. This development is important as it highlights the necessity of strict adherence to privacy laws, especially when handling sensitive biometric data. Specifically, the broad interpretation of “identity” and “verification,” the explicit consent requirement, and the quasi-constitutional nature of privacy protection in Quebec all provide cause for businesses to be diligent in their compliance efforts. Businesses may want to ensure they obtain explicit consent from individuals before collecting and using biometric data. The CAI’s decision on the grocer’s project serves as a critical reminder that privacy protection is taken very seriously in Quebec, and businesses may want to be proactive in ensuring their practices comply with the stringent requirements of the law. Given the CAI’s broad powers and the quasi-constitutional nature of privacy protection in Quebec, businesses can expect more restrictive decisions in the future.

California Privacy Agency Extracts Civil Penalties in its First Settlement Not Involving Data Brokers

Companies in all industries take note: regulators are scrutinizing how companies offer and manage privacy rights requests and looking into the nature of vendor processing in connection with application of those requests. This includes applying the proper verification standards and how cookies are managed. Last week, the California Privacy Protection Agency (“CPPA” or “Agency”) provided yet another example of this regulatory focus in its Stipulated Final Order (“Order”) with automotive company, American Honda Motor Co., Inc. (“Honda”).

The CPPA alleged that Honda violated the California Consumer Privacy Act (“CCPA”) by:

requiring Californians to verify themselves where verification is not required or permitted (the right to opt-out of sale/sharing and the right to limit) and provide excessive personal information to exercise privacy rights subject to verification (know, delete, correct);

using an online cookie management tool (often known as a CMP) that failed to offer Californians their privacy choices in a symmetrical or equal way and was confusing;

requiring Californians to verify that they gave their agents authority to make opt-out of sale/sharing and right to limit requests on their behalf; and

sharing consumers’ personal information with vendors, including ad tech companies, without having in place contracts that contain the necessary terms to protect privacy in connection with their role as either a service provider, contractor, or third party.

This Order illustrates the potential fines and financial risks associated with non-compliance with the state privacy laws. Of the $632,500 administrative fine lodged against the company, the Agency clearly spelled out that $382,500 of the fine accounts for 153 violations – $2,500 per violation – that are alleged to have occurred with respect to Honda’s consumer privacy rights processing between July 1 and September 23, 2023. It is worth emphasizing that the Agency lodged the maximum administrative fine – “up to two thousand five hundred ($2,500)” – that is available to it for non-intentional violations for each of the incidents where consumer opt-out / limit rights were wrongly applying verification standards. It Is unclear to what the remaining $250,000 in fines were attributed, but they are presumably for the other violations alleged in the order, such as disclosing PI to third parties without having contracts with the necessary terms, confusing cookie and other consumer privacy requests methods, and requiring excessive personal data to make a request. It is unclear the number of incidents that involved those infractions but based on likely web traffic and vendor data processing, the fines reflect only a fraction of the personal information processed in a manner alleged to be non-compliant.

The Agency and Office of the Attorney General of California (which enforces the CCPA alongside the Agency) have yet to seek truly jaw-dropping fines in amounts that have become common under the UK/EU General Data Protection Regulation (“GDPR”). However, this Order demonstrates California regulators’ willingness to demand more than remediation. It is also significant that the Agency requires the maximum administrative penalty on a per-consumer basis for the clearest violations that resulted in denial of specific consumers’ rights. This was a relatively modest number of consumers: “119 Consumers who were required to provide more information than necessary to submit their Requests to Opt-out of Sale/Sharing and Requests to Limit, 20 Consumers who had their Requests to Opt-out of Sale/Sharing and Requests to Limit denied because Honda required the Consumer to Verify themselves before processing the request, and 14 Consumers who were required to confirm with Honda directly that they had given their Authorized Agents permission to submit the Request to Opt-out of Sale/Sharing and Request to Limit on their behalf.” The fines would have likely been greater if applied to all Consumers who accessed the cookie CMP, or that made requests to know, delete, or correct. Further, it is worth noting that many companies receive thousands of consumer requests per year (or even per month), and the statute of limitations for the Agency is five years; applying the per-consumer maximum fine could therefore result in astronomical fines for some companies.

Let us also not forget that regulators also have injunctive relief at their disposal. Although, the injunctive relief in this Order was effectively limited to fixing alleged deficiencies, it included “fencing in” requirements such as use of a UX designer to evaluate consumer request “methods – including identifying target user groups and performing testing activities, such as A/B testing, to access user behavior” – and reporting of consumer request metrics for five years. More drastic relief, such as disgorgement or prohibiting certain data or business practices, are also available. For instance, in a recent data broker case brought by the Agency, the business was barred from engaging in business as a data broker in California for three years.

We dive into each of the allegations in the present case further below and provide practical takeaways for in-house legal and privacy teams to consider.

Requiring consumers to provide more info than necessary to exercise verifiable requests and requiring verification of CCPA sale/share opt-out and sensitive PI limitation requests.

The Order alleges two main issues with Honda’s rights request webform:

Honda’s webform required too many data points from consumers (e.g., first name, last name, address, city, state, zip code, email, phone number). The Agency contends that requiring all of this information necessitates that consumers provide more information than necessarily needed to exercise their verifiable rights considering that the Agency alleged that “Honda generally needs only two data points from the Consumer to identify the Consumer within its database.” The CPPA and its regulations allow a business to seek additional personal information if necessary to verify to the requisite degree of certainty required under the law (which varies depending on the nature of the request and the sensitivity of the data and potential harm of disclosure, deletion or change), or to reject the request and provide alternative rights responses that require lesser verification (e.g., treat a request of a copy of personal information as a right to know categories of person information). However, the regulations prohibit requiring more personal data than is necessary under the particular circumstances of a specific request. Proposed amendments the Section 7060 of the CCPA regulations also demonstrate the Agency’s concern about requiring more information than is necessary to verify the consumer.

Honda required consumers to verify their Requests to Opt-Out of Sale/Sharing and Requests to Limit, which the CCPA prohibits.

In addition to these two main issues, the Agency also alluded to (but did not directly state) that the consumer rights processes amounted to dark patterns (Para. 38). The CPPA cited to the policy reasons behind differential requirements as to Opt-Out of Sale/Sharing and Right to Limit; i.e., so that consumers can exercise Opt-Out of Sale/Sharing and Right to Limit requests without undue burden, in particular, because there is minimal or nonexistent potential harm to consumers if such requests are not verified.

In the Order, the CPPA goes on to require Honda to ensure that its personnel handling CCPA requests are trained on the CCPA’s requirements for rights requests, which is an express obligation under the law, and confirming to the Agency that it has provided such training within 90 days of the Order’s effective date.

Practical Takeaways

Configure consumer rights processes, such as rights request webforms, to only require a consumer to provide the minimum information needed to initiate and verify (if permitted) the specific type of request. This may be difficult for companies that have developed their own webforms, but most privacy tech vendors that offer webforms and other consumer rights-specific products allow for customizability. If customizability is not possible, companies may have to implement processes to collect minimum information to initiate the request and follow up to seek additional personal information if necessary to meet CCPA verification standards as may be applicable to the specific consumer and the nature of the request.

Do not require verification of do not sell/share and sensitive PI limitation requests (note, there are narrow fraud prevention exceptions here, though, that companies can and should consider in respect of processing Opt-Out of Sale/Sharing and Right to Limit requests).

Train personnel handling CCPA requests (including those responsible for configuring rights request “channels”) to properly intake and respond to them.

Include instructions on how to make the various types of requests that are clear and understandable, and that track the what the law permits and requires.

Requiring consumers to directly confirm with Honda that they had given permission to their authorized agent to submit opt-out of sale/sharing sensitive PI limitation requests

The CPPA’s Order also outlines that Honda allegedly required consumers to directly confirm with Honda that they gave permission to an authorized agent to submit Opt-Out of Sale/Sharing and Right to Limit requests on their behalf. The Agency took issue with this because under the CCPA, such direct confirmation with the consumer regarding authority of an agent is only permitted as to requests to delete, correct, and know.

Practical Takeaways: When processing authorized agent requests to Opt-Out of Sale/Sharing or Right to Limit, avoid directly confirming with the consumer or verifying the identity of the authorized agent (the latter is also permitted in respect of requests to delete, correct, and know). Keep in mind that what agents may request, and agent authorization and verification standards, differ from state-to-state.

Failure to provide “symmetry in choice” in its cookie management tool

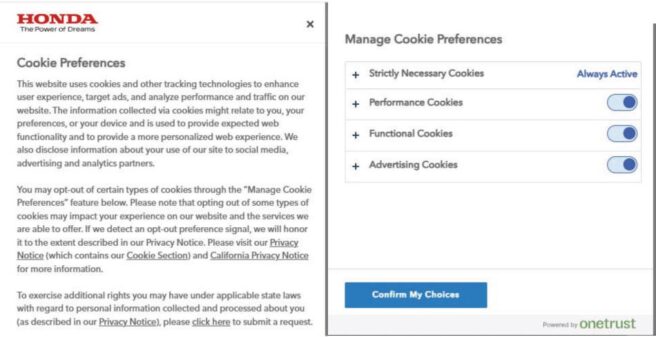

The Order alleges that, for a consumer to turn off advertising cookies on Honda’s website (cookies which track consumer activity across different websites for cross-context behavioral advertising and therefore require an Opt-out of Sale/Sharing), consumers must complete two steps: (1) click the toggle button to the right of Advertising Cookies and (2) click the “Confirm My Choices” button,” shown below:

The Order compares this opt-out process to that for opting back into advertising cookies following a prior opt-out. There, the Agency alleged that if consumers return to the cookie management tool (also known as a consent management platform or “CMP”) after turning “off” advertising cookies, an “Allow All” choice appears (as shown in the below graphic). This is likely a standard configuration of the OneTrust CMP that can be modified to match the toggle and confirm approach used for opt-out. Thus, the CPPA alleged, consumers need only take one step to opt back into advertising cookies when two steps are needed to opt-out, in violation of and express requirement of the CCPA to have no more steps to opt-in than was required to opt-out.

The Agency took issue with this because the CCPA requires businesses to implement request methods that provide symmetry in choice, meaning the more privacy-protective option (e.g., opting-out) cannot be longer, more difficult, or more time consuming than the less privacy protective option (e.g., opting-in).

The Agency also addressed the need for symmetrical choice in the context of “website banners,” also known as cookie banners, pointing to an example cited as insufficient symmetry in choice from the CCPA regulations – i.e., using “’Accept All’ and ‘More Information,’ or ‘Accept All’ and ‘Preferences’ – is not equal or symmetrical” Because it suggests that the company is seeking and relying on consent (rather than opt-out) to cookies, and where consent is sought acceptance and acceptance must be equally as easy to choose. The CCPA further explained that “[a]n equal or symmetrical choice” in the context of a website banner seeking consent for cookies “could be between “Accept All” and “Decline All.” Of course, under CCPA consent to even cookies that involve a Share/Sale is not required, but the Agency is making clear that where consent is sought there must be symmetry in acceptance and denial of consent.

The CPPA’s Order also details other methods by which the company should modify its CCPA requests procedures including (i) separating the methods for submitting sale/share opt-out requests and sensitive PI limitation requests from verifiable consumer requests (e.g., requests to know, delete, and correct); (ii) including the link to manage cookie preferences within Honda’s Privacy Policy, Privacy Center, and website footer; and (iii) applying global privacy control (“GPC”) preference signals for opt-outs to known consumers consistent with CCPA requirements.

Practical Takeaways

It is unclear whether the company configured the cookie management tool in this manner deliberately or if the choice of the “Allow All” button in the preference center was simply a matter of using a default configuration of the CMP, a common issue with CMPs that are built off of a (UK/EU) GDPR consent model. Companies should pay close attention to the configuration of their cookie management tools, including in both the cookie banner (or first layer), if used, and the preference center (shown above), and avoid using default settings and configurations provided by providers that are inconsistent with state privacy laws. Doing so will help mitigate the risk of choice asymmetry presented in this case, and the risks discussed in the following three bullets.

State privacy laws like the CCPA are not the only reason to pay close attention and engage in meticulous legal review of cookie banner and preference center language, and proper functionality and configuration of cookie management tools.

Given the onslaught of demands and lawsuits from plaintiffs’ firms under the California Invasion of Privacy Act and similar laws – based on cookies, pixels, and other tracking technologies – many companies turn to cookie banner and preference center language to establish an argument for a consent defense and therefore mitigate litigation risk. In doing so it is important to bear in mind the symmetry of choice requirements of state consumer privacy laws. One approach is to make it clear that acceptance is of the site terms and privacy practices, which include use of tracking by the operator and third parties, subject to the ability to opt-out of some types of cookies. This can help establish consent to use of cookies by use of the site after notice of cookie practices, while not suggesting that cookies are opt-in, and having lack of symmetry in choice.

In addition, improper wording and configuration of cookie tools – such as providing an indication of an opt-in approach (“Accept Cookies”) when cookies in fact already fired upon the user’s site visit, or that “Reject All” opts the user out of all, including functional and necessary cookies that remain “on” after rejection – present risks under state unfair and deceptive acts and practices (UDAAP) and unfair competition laws, and make the cookie banner notice defense to CIPA claims potentially vulnerable since the cookies fire before the notice is given.

Address CCPA requirements for GPC, linking to the business’s cookie preference center, and separating methods for exercising verifiable vs. non-verifiable requests. Where the business can tie a GPC signal to other consumer data (e.g., the account of a logged in user), it must also apply the opt-out to all linkable personal information.

Strive for clear and understandable language that explains what options are available and the limitations of those options, including cross-linking between the CMP for cookie opt-outs and the main privacy rights request intake for non-cookie privacy rights, and explain and link to both in the privacy policy or notice.

Make sure that the “Your Privacy Choices” or “Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information” link gets the consumer to both methods. Also make sure the opt-out process is designed so that the required number of steps to make those opt-outs is not more than to opt-back in. For example, linking first to the CMP, which then links the consumer rights form or portal, rather than the other way around, is more likely to avoid the issue with additional steps just discussed.

Failure to produce contracts with advertising technology companies

The Agency’s Order goes on to allege that Honda did not produce contracts with advertising technology companies despite collecting and selling/sharing PI via cookies on its website to/with these third parties. The CPPA took issue with this because the CCPA requires a written contract meeting certain requirements to be in place between a business and PI recipients that are a CCPA service provider, contractor, or third party in relation to the business. We have seen regulators request copies of contracts with all data recipients in other enforcement inquiries.

Practical Takeaways

Vendor and contract management are a growing priority of privacy regulators, in California and beyond, and should be a priority for all companies. Be prepared to show that you have properly categorized all personal data recipients, and have implemented and maintain processes to ensure proper contracting practices with vendors, partners, and other data recipients, which should include a diligence and assessment process to ensure that the proper contractual language is in place with the data recipient based on the recipient’s data processing role. To state it another way, it may not be proper as to certain vendors to simply put in place a data processing agreement or addendum with service provider/processor language. For instance, vendors that process for cross-context behavioral advertising cannot qualify as a service provider/contractor. In order to correctly categorize cookie and other vendors as subject to opt-out or not, this determination is necessary.

Attention to contracting is important under the CCPA in particular because different language is required depending on whether the data recipient constitutes a “third party,” “service provider,” or a “contractor,” the CCPA requires different contracting terms be included in the agreements with each of those three types of personal information recipients. Further, in California, the failure to have all of the required service provider/contractor contract terms will convert the recipient to a third party and the disclosure into a sale.

Conclusion

This case demonstrates the need for businesses to review their privacy policies and notices, and audit their privacy rights methods and procedures to ensure that they are in compliance with applicable state privacy laws, which have some material differences from state-to-state. We are aware of enforcement actions in progress not only in California, but other states including Oregon, Texas, and Connecticut, and these states are looking for clarity as to what specific rights their residents have and how to exercise them. Further, it can be expected that regulators will start looking beyond obvious notice and rights request program errors to data knowledge and management, risk assessment, minimization, and purpose and retention limitation obligations. Compliance with those requirements requires going beyond “check the box” compliance as to public facing privacy program elements and to the need to have a mature, comprehensive and meaningful information governance program.

PLOT TWIST: Legal Lead Generator Sued in TCPA Class Action

In an ironic twist, Intake Desk LLC, a company that recruits plaintiffs for personal injury lawsuits and uses the tagline “File More Mass Tort Cases,” now finds itself on the other side of the courtroom—as a defendant in a TCPA class action.

The Complaint in Emily Teman v. Intake Desk LLC (Mar. 19, 2025, D. Mass.) alleges that Intake Desk violated the TCPA by making telemarketing calls to Plaintiff Teman and other putative class members while their numbers were listed on the National Do Not Call Registry and without their written consent, as well as by calling individuals who had previously requested not to receive such calls.

Plaintiff Teman claims she received more than a dozen calls from Intake Desk over several months in 2023, allegedly attempting to sign her up for personal injury lawsuits related to talcum powder. However, Teman asserts that she never consented to these calls, and that her number has been on the National Do Not Call Registry since 2003.

Interestingly, Teman filed another TCPA class action with similar allegations against Select Justice, LLC, a self-proclaimed advocacy group “committed to helping injured individuals seek justice and compensation.” In Emily Teman v. Select Justice, LLC (Mar. 20, 2025, D. Mass.), Teman alleges that she received more than a dozen calls from Select Justice over several months in 2023, including multiple harassing voicemails from different representatives. According to the Complaint, the voicemails implied that Teman had contacted Select Justice to join class action suits related to talcum powder and rideshare assault. Teman asserts that she had never been a customer of Select Justice and never consented to receive calls from them. The Complaint further alleges that the calls prompted Teman to file a Consumer Complaint with the Massachusetts Attorney General’s Office against Select Justice on January 26, 2024.

While the Complaint against Intake Desk states that Teman “never made an inquiry into” its services, the Complaint against Select Justice alleges that she “was not interested in Select Justice’s services.” Perhaps this is just a trivial semantic difference – but in TCPAWorld, every word carries weight.

Joint Alert Warns of Medusa Ransomware

On March 12, 2025, a joint cybersecurity advisory was issued by the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the Multi-State Information Sharing and Analysis Center to advise companies about the tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs), and indicators of compromise (IOCs) to protect themselves against Medusa ransomware.

According to the advisory:

Medusa is a ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) variant first identified in June 2021. As of February 2025, Medusa developers and affiliates have impacted over 300 victims from a variety of critical infrastructure sectors with affected industries including medical, education, legal, insurance, technology, and manufacturing. The Medusa ransomware variant is unrelated to the MedusaLocker variant and the Medusa mobile malware variant per the FBI’s investigation.

The advisory provides technical details on how Medusa gains access to systems, including phishing campaigns as the primary method for stealing credentials. The group also exploits unpatched software vulnerabilities, which reinforces the importance of timely patching.

The threat actors exfiltrate the victim’s data and then deploy the encryptor, gaze.exe, on files while disabling Windows Defender and other antivirus tools. The encrypted files use the .medusa file extension. They then contact the victim within 48-hours and use the .onion data leak site for communication.

The advisory lists the IOCs and TTPs used in the attacks. IT professionals may wish to review them and apply mitigation tactics. The mitigations listed in the advisory are lengthy and worth consulting.

Insider Threats: Potential Signs and Security Tips

In recent news, New York’s Stram Center for Integrative Medicine reported a security incident involving an employee misusing a patient’s payment card information. According to a breach report filed with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office for Civil Rights, the incident may have involved 15,263 patients’ information—even though the bad actor only misused one patient’s payment card. The individual has been arrested and is no longer employed. According to the Stram Center, social security numbers are not involved, but it is offering complimentary credit monitoring and identity protection services to affected individuals.

When we hear “data breach,” we’re likely to think of ransomware incidents, business email compromises, and other cyberattacks from external threats. However, according to a Cybersecurity Insiders report, 83% of organizations reported at least one insider attack in 2024. According to IBM’s 2024 Cost of a Data Breach report, data breaches resulting from insider threats were the costliest, at $4.99 million on average. While insider threats may not make headlines as frequently, organizations should take measures to mitigate risks surrounding insider data incidents. Insider threats include unintentional errors, such as emailing personal information to the wrong recipient, misplacing documents, and speaking about personal information among those without authorized access. Insider threats also include malicious insider threats, such as disgruntled employees.

Organizations should monitor for several signs that may signal a malicious insider threat:

Timing of access – Malicious insiders may access the network and systems at unusual times. If an employee typically only works night shifts but the user’s access logs suddenly reflect daytime activity, this could indicate potential malicious activity.

Unexpected spikes in network traffic – Atypical spikes in network traffic might reflect that a user is downloading or copying large volumes of data.

Unusual requests – If a user is requesting access to applications or information that are beyond the scope of their role or unusual for team members in similar roles, this could signal malicious intent.

Several security practices can help organizations reduce the risk of insider attacks:

Endpoint monitoring – Constant endpoint monitoring can help organizations analyze user and entity behavior, scan networks, and detect potential early signs of insider activity.

Role-based access – Employees should only have access to the information that they need to fulfill their job responsibilities. Providing employees access on a least-privilege basis helps minimize the risk of unauthorized access and misuse.

Culture of awareness – Regular cybersecurity training, including on best practices such as locking one’s computer and maintaining proper password hygiene, can help minimize unauthorized insider access.

Since malicious insiders often already have some level of existing access to an organization’s systems and knowledge of business practices and organization policies, such threats can cause significant harm. Insider threat prevention should be an integral component of all organizations’ overall cybersecurity posture.

CPPA Settles Alleged CCPA Violations with Honda

Last week, the California Privacy Protection Agency (CPPA) settled its first non-data broker enforcement action against American Honda Motor Co. for a $632,500 fine and the implementation of certain remedial actions.

The CPPA alleged that Honda violated the California Consumer Privacy Act as amended by the California Privacy Rights Act (collectively the CCPA) by:

Requiring consumers to provide more information than necessary to exercise their rights under the CCPA. When submitting a request, a consumer is required by Honda’s webform to provide their first name, last name, address, city, state, zip code, email, and phone number. The CPPA alleged that this violated the CCPA by requiring a higher level of verification than required for an opt-out or to limit the use of certain information requests.

Requiring consumers to directly confirm that they have permitted another individual to act as their authorized agent to submit a request to opt-out or limit use. While a company may request written documentation indicating that an individual is an authorized agent for a consumer, a company may not require a consumer to directly confirm that they have provided the permission; companies may only contact consumers directly for requests to know, access, and correct.

Failing to implement a cookie management tool that provides symmetrical choice when a consumer submits requests to opt-out of sale and/or sharing and consents to the use of their personal information. The CPPA alleged that Honda’s website automatically allows cookies by default. To turn off advertising cookies, the user must toggle a button next to “Advertising Cookies” and then click “Confirm my Choices,” but to opt back into advertising cookies, the consumer only needs to press one button. The CPPA alleges that by providing one step to opt-in but two steps to opt-out, Honda did not provide equal or symmetrical choices as the CCPA requires.

Failing to execute written contracts with third-party advertising companies with whom it sold, shared, and/or disclosed consumer personal information. The CPPA alleged that Honda failed to execute CCPA-compliant agreements with the third-party cookie providers it uses on its website and that it sells, shares, and/or discloses personal information for advertising and marketing across different websites.

To resolve the allegations, Honda agreed to:

Implement a new and simpler process for Californians to assert their privacy rights

Update its cookie preference tool to include a “Reject All” button in addition to the “Accept All” button

Separate the methods for submitting requests to opt-out and limit the use of certain information from other rights under the CCPA

Train its employees

Consult a user experience designer to evaluate its methods for submitting privacy requests

The settlement amount is supported by the CPPA by calling out the number of consumers whose rights were implicated by some of Honda’s practices, which emphasizes that the CPPA will determine a fine on a per-violation basis. If your company hasn’t done so already, be sure to update your CCPA compliance program and dot the “I’s” and cross the “t’s” when it comes to your website’s privacy policy regarding cookie preferences and third-party advertisers.

Valenzuela v. The Kroger Co. Chatbot Wiretapping Case Dismissed; Implications and Takeaways for Businesses

A recent noteworthy decision from a federal court in California provides helpful guidance for companies deploying chatbots and other types of tracking technology on their websites, but at the same time highlights the nuances and high wire act of safely collecting consumer information versus stepping over the line.

In Valenzuela v. The Kroger Co., the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California dismissed a proposed class action filed against the grocery chain Kroger, finding that the plaintiff did not have a viable argument under the California Invasion of Privacy Act (CIPA). Because plaintiffs’ attorneys have recently been using CIPA to bring cases against a large number of companies, this decision is potentially an important decision in privacy jurisprudence. However, the narrowness of the decision leaves open other paths for plaintiffs and demonstrates the need for companies to carefully and thoughtfully assess what online tracking they conduct in order to minimize their risk of class action litigation.

The plaintiff in the case alleged Kroger, through a third-party vendor called Emplifi, unlawfully intercepted and recorded chat-based conversations between customers and Kroger’s website (i.e., communications with a “chatbot” on the website). The central claim was that Kroger “aided and abetted” Emplifi’s allegedly wrongful conduct of allowing Meta Platforms Inc. to mine data collected through Emplifi’s chatbots (including the one deployed on Kroger’s website) to gather information about user interests and target ads to those users on Meta’s social media platforms like Facebook and Instagram.

More specifically, the case was brought under Section 631(a) of CIPA which prohibits, among other things, any person from:

Tapping or making unauthorized connections with a telegraph or telephone line;

Willfully and without consent reading the contents of communications in transit;

Using information obtained via such interception; or

“Aiding, agreeing with, employing or conspiring with” any person to commit these acts.1

After a lengthy procedural back-and-forth, the Court allowed the plaintiff to proceed only under the “aiding and abetting” theory (the fourth prong). In its ruling, the Court emphasized that to hold Kroger liable under the fourth prong, the plaintiff needed to demonstrate that Kroger knew—or plausibly should have known—of Emplifi’s alleged unlawful eavesdropping or otherwise acted with knowledge or intent to facilitate it. The plaintiff pointed to the vendor’s marketing materials and the cost and ease with which the chatbot was installed on the Kroger website, arguing that Kroger must have known Emplifi was intercepting conversations without customers’ consent. The Court rejected this argument, holding “[i]t is not a plausible inference that because Emplifi could ‘quickly and cheaply’ deploy the bot, Kroger should have known Emplifi harvested user data.”

The Court ruled that because there was not a plausible allegation that Kroger had actual or constructive knowledge of the alleged unlawful sharing of chatbot communications with social media companies, Kroger could not be held liable for “aiding and abetting” the third parties’ alleged violation of CIPA.

What the Kroger Ruling Means for Businesses

Although this decision was made at the district court level and does not have a precedential effect, the Court’s reasoning provides a roadmap of what companies should be aware of when considering integrating chatbots or other large language model enabled third-party technologies onto their websites. Of note, this case focused on section 631(a) of CIPA only, and did not involve section 638.51(a), which prohibits the installation of “pen registers” or “tap and trace” devices without appropriate approvals and which plaintiffs are regularly claiming apply to website tracking software. As a result, even if the rationale from the Kroger decision is extended to other cases by other courts, companies will continue to face the risks associated with claims brought 638.51(a). Nonetheless, there are valuable lessons to be learned from the Kroger decision and other recent court decisions:

“Knowledge” of a third party’s actions is a key to a company’s liability. This includes constructive knowledge, that a company could gain from the third-party’s documentation and marketing communications as to the capabilities of their products.

Courts will require specific, fact-based allegations showing a company’s awareness and intent regarding any purported interception of communications.

Plaintiffs with more robust support for allegations of unauthorized data collection may have more success bringing similar claims.

Additionally, and as always, litigation defense is costly and even a successful defense can be a burden on a company. Even though Kroger won in this case, it took almost three years of litigation expenses to obtain that victory. Taking proactive steps to assess website tracking tool deployment can lower the risk of litigation in the first place and avoid these costs:

Ensuring that proper notice is given to, and appropriate consent is obtained from, website visitors

When onboarding third-party software providers, businesses should conduct thorough due diligence on data collection and sharing practices.

Contractual provisions should clarify that any data recording or sharing be done in compliance with all applicable laws, and that providers will indemnify the business if violations arise.

Footnotes

[1] The plaintiff in this matter also sought to bring a claim under §632.7 of CIPA (illegal interception of cellular communications for individuals who used the chatbot from their internet-enabled smartphones). That claim was dismissed with prejudice in March of 2024 with the Court finding that section of CIPA only applies to communications between two or more cellular phones and not between a cellular phone and a website.

AI Governance: The Problem of Shadow AI

If you hang out with CISOs like I do, shadow IT has always been a difficult problem. Shadow IT refers to refers to “information technology (IT) systems deployed by departments other than the central IT department, to bypass limitations and restrictions that have been imposed by central information systems. While it can promote innovation and productivity, shadow IT introduces security risks and compliance concerns, especially when such systems are not aligned with corporate governance.”

Shadow IT has been a longstanding problem as IT professionals can’t implement security measures and guidelines when they are unaware of its use.

Now that artificial intelligence (AI) is widely used for purposes including work, it is imperative that organizations address its governance, as they previously addressed employees’ use of IT assets. Otherwise, employees will use AI tools without the organization’s knowledge and outside of its acceptable use policies, exacerbating the problem of shadow AI in the organization.

A recent TechRadar article concluded that “you almost certainly have a shadow AI problem.” The risks of having shadow AI in the organization include: “the leakage of sensitive or proprietary data, which is a common issue when employees upload documents to an AI service such as ChatGPT, for example, and its contents become available to users outside of the company. But it could also lead to serious data quality problems where incorrect information is retrieved from an unapproved AI source which may then lead to bad business decisions.” And don’t forget about the problem of hallucinations.

Implementing an AI Governance Program is one way to address the shadow AI problem. AI Governance programs differ depending on business needs, but all of them address who owns the program, AI tools usage, what tools are sanctioned, how AI tools can be used, guardrails around the risks of data loss, data integrity and accuracy, and user training and education. Governing the use of AI tools in an organization is similar to governing the use of IT assets. The most important thing is to get started before shadow AI gets out of hand.

Privacy Tip #436 – Microsoft Warns of Crypto Wallet Scanning Malware StilachiRAT

A Microsoft blog post reported that incident response researchers uncovered a remote access trojan in November 2024 (dubbed StilachiRAT) that “demonstrates sophisticated techniques to evade detection, persist in the target environment, and exfiltrate sensitive data.”

According to Microsoft, the StilachiRAT threat actors use different methods to steal information from the victim, including credentials stored in the browser, scans for digital wallet information, system information, and data stored on the clipboard.

Once inside the victim’s system, StilachiRAT scans the configuration data of 20 cryptocurrency wallet extensions for the Google Chrome browser, extracting and decrypting saved credentials from Google Chrome. The 20 cryptocurrency wallet extensions targeted are listed in the blog article. The article also lists recommended mitigations.

One takeaway from the article is to not store critical credentials in Chrome, a common and simple security measure. If a threat actor gains access to these credentials, multiple applications could be at risk. You may wish to consider which passwords you are saving in Chrome and refrain from saving the credentials for any banking or cryptocurrency platforms, as well as for access to your employer’s system. These are credentials worth memorizing.

Reminder: New York Cybersecurity Reporting Deadline April 15, 2025; New Regulations Effective May 1, 2025

Covered entities regulated by the New York State Department of Financial Services (NYDFS) must submit cybersecurity compliance forms by April 15, 2025. New sets of requirements for system monitoring and access privileges, enacted as part of 2023 amendments to the NYDFS cybersecurity regulations, will take effect on May 1 and November 1, 2025.

Quick Hits

Covered entities in New York must submit their annual cybersecurity compliance forms to the NYDFS by April 15, 2025, either certifying material compliance or acknowledging material noncompliance.

Starting May 1, 2025, new requirements will be implemented, including enhanced access management protocols, vulnerability management through automated scans, and improved monitoring measures to protect against cybersecurity threats.

In November 2023, NYDFS amended its comprehensive cybersecurity regulations with the changes set to take effect on a rolling basis over the following two years. Several amendments went into effect on November 1, 2024, and several more are set to take effect on May 1 and November 1, 2025.

The regulations apply to NYDFS-regulated entities, which include financial institutions, insurance companies, insurance agents and brokers, banks, trusts, mortgage banks, mortgage brokers and lenders, money transmitters, and check cashers. Certain large companies regulated by NYDFS (Class A companies) have additional requirements, while certain small businesses are exempt from specific regulations.

April 15 Annual Compliance Reporting Deadline

The NYDFS cybersecurity regulations require financial services companies and other covered entities to file annual notices of compliance to the superintendent of NYDFS by April 15, 2025, covering the prior calendar year. Under the amended regulations, covered entities must submit either a certification of material compliance with the cybersecurity requirements or an acknowledgment of noncompliance. In the acknowledgment of noncompliance, covered entities must (1) acknowledge the entity did not materially comply, (2) identify all sections of the regulations with which the entity has not complied, and (3) provide a “remediation timeline or confirmation that remediation has been completed.”

Covered entities must submit the certification or acknowledgment electronically using the NYDFS portal and the form on the NYDFS website.

New Requirements Effective May 1, 2025

Several requirements of the amended NYDFS cybersecurity regulations take effect on May 1, 2025, for nonexempt covered entities. Class A companies are subject to additional requirements that are not addressed below.

Access Privileges and Management

The amended regulations will require covered entities to limit user access privileges based on job function, limit the number and use of privileged accounts, periodically (but at least annually) review user access privileges, disable or securely configure protocols that permit remote control of devices, and “promptly” terminate accounts after a user’s departure. The regulations further require covered entities to implement a written password policy that meets industry standards.

Vulnerability Management

In addition to penetration testing, the amended regulations will require covered entities to perform “automated scans of information systems” and manual review of systems not covered by such scans to determine potential vulnerabilities.

System Monitoring

The amended regulations will require covered entities to implement “risk-based controls designed to protect against malicious code.” This includes monitoring and filtering web traffic and email to block malicious code.

New Requirements Effective November 1, 2025

The final batch of requirements under the amended cybersecurity regulations take effect on November 1, 2025. Covered entities will be required to implement multifactor authentication for all individuals to access the entity’s information systems. If the entity has a chief information security officer (CISO), the CISO “may approve in writing the use of reasonably equivalent or more secure compensating controls,” which must be reviewed at least annually.

Additionally, covered entities will be required to “implement written policies and procedures designed to produce and maintain a complete, accurate and documented asset inventory of the covered entity’s information systems.” The policies will be required to include methods to track information for each asset and “the frequency required to update and validate” the entity’s asset inventory.

Next Steps

Covered entities may want to take steps to comply with the April 15 compliance reporting deadline and the next round of cybersecurity requirements, which will take effect on May 1, 2025. Additional requirements for certain written policies and procedures and the implementation of multifactor authentication are set to take effect on November 1, 2025.

FBI Warns of Hidden Threats in Remote Hiring: Are North Korean Hackers Your Newest Employees?

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) recently warned employers of increasing security risks from North Korean workers infiltrating U.S. companies by obtaining remote jobs to steal proprietary information and extort money to fund activities of the North Korean government. Companies that rely on remote hires face a tricky balancing act between rigorous job applicant vetting procedures and ensuring that new processes are compliant with state and federal laws governing automated decisionmaking and background checks or consumer reports.

Quick Hits

The FBI issued guidance regarding the growing threat from North Korean IT workers infiltrating U.S. companies to steal sensitive data and extort money, urging employers to enhance their cybersecurity measures and monitoring practices.

The FBI advised U.S. companies to improve their remote hiring procedures by implementing stringent identity verification techniques and educating HR staff on the risks posed by potential malicious actors, including the use of AI to disguise identities.

Imagine discovering your company’s proprietary data posted publicly online, leaked not through a sophisticated hack but through a seemingly legitimate remote employee hired through routine practices. This scenario reflects real threats highlighted in a series of recent FBI alerts: North Korean operatives posing as remote employees at U.S. companies to steal confidential data and disrupt business operations.

On January 23, 2025, the FBI issued another alert updating previous guidance to warn employers of “increasingly malicious activity” from the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, or North Korea, including “data extortion.” The FBI said North Korean information technology (IT) workers have been “leveraging unlawful access to company networks to exfiltrate proprietary and sensitive data, facilitate cyber-criminal activities, and conduct revenue-generating activity on behalf of the regime.”

Specifically, the FBI warned that “[a]fter being discovered on company networks, North Korean IT workers” have extorted companies, holding their stolen proprietary data and code for ransom and have, in some cases, released such information publicly. Some workers have opened user accounts on code repositories, representing what the FBI described as “a large-scale risk of theft of company code.” Additionally, the FBI warned such workers “could attempt to harvest sensitive company credentials and session cookies to initiate work sessions from non-company devices and for further compromise opportunities.”

The alert came the same day the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) announced indictments against two North Korean nationals and two U.S. nationals alleging they engaged in a “fraudulent scheme” to obtain remote work and generate revenue for the North Korean government, including to fund its weapons programs.

“FBI investigation has uncovered a years-long plot to install North Korean IT workers as remote employees to generate revenue for the DPRK regime and evade sanctions,” Assistant Director Bryan Vorndran of the FBI’s Cyber Division said in a statement. “The indictments … should highlight to all American companies the risk posed by the North Korean government.”

Data Monitoring

The FBI recommended that companies take steps to improve their data monitoring, including:

“Practice the Principle of Least Privilege” on company networks.

“Monitor and investigate unusual network traffic,” including remote connections and remote desktops.

“Monitor network logs and browser session activity to identify data exfiltration.”

“Monitor endpoints for the use of software that allows for multiple audio/video calls to take place concurrently.”

Remote Hiring Processes

The FBI further recommended that employers strengthen their remote hiring processes to identify and screen potential bad actors. The recommendations come amid reports that North Korean IT workers have used strategies to defraud companies in hiring, including stealing the identities of U.S. individuals, hiring U.S. individuals to stand in for the North Korean IT workers, or using artificial intelligence (AI) or other technologies to disguise their identities. These techniques include “using artificial intelligence and face-swapping technology during video job interviews to obfuscate their true identities.”

The FBI recommended employers:

implement processes to verify identities during interviews, onboarding, and subsequent employment of remote workers;

educate human resources (HR) staff and other hiring managers on the threats of North Korean IT workers;

review job applicants’ email accounts and phone numbers for duplicate contact information among different applicants;

verify third-party staffing firms and those firms’ hiring practices;

ask “soft” interview questions about specific details of applicants’ locations and backgrounds;

watch for typos and unusual nomenclature in resumes; and

complete the hiring and onboarding process in person as much as possible.

Legal Considerations

New vendors have entered the marketplace offering tools purportedly seeking to solve such remote hiring problems; however, companies may want to consider the legal pitfalls—and associated liability—that these processes may entail. These considerations include, but are not limited to:

Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) Implications: If a third-party vendor evaluates candidates based on personal data (e.g., scraping public records or credit history), it may be considered a “consumer report.” The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) issued guidance in September 2024 taking that position as well, and to date, that guidance does not appear to have been rolled back.

Antidiscrimination Laws: These processes, especially as they might pertain to increased scrutiny or outright exclusion of specific demographics or countries, could disproportionately screen out protected groups in violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (e.g., causing disparate impact based on race, sex, etc.), even if unintentional. This risk exists regardless of whether the processes involve automated or manual decisionmaking; employers may be held liable for biased outcomes from AI just as if human decisions caused them—using a third-party vendor’s tool is not a defense.

Privacy Laws: Depending on the jurisdiction, companies’ vetting processes may implicate transparency requirements under data privacy laws, such as the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the European Economic Area (EEA), when using third-party sources for candidate screening. Both laws require clear disclosure to applicants about the types of personal information collected, including information obtained from external background check providers, and how this information will be used and shared.

Automated Decisionmaking Laws: In the absence of overarching U.S. federal legislation, states are increasingly filling in the gap with laws regarding automated decisionmaking tools, covering everything from bias audits to notice, opt-out rights, and appeal rights. If a candidate is located in a foreign jurisdiction, such as in the EEA, the use of automated decisionmaking tools could trigger requirements under both the GDPR and the recently enacted EU Artificial Intelligence Act.

It is becoming increasingly clear that multinational employers cannot adopt a one-size-fits-all vetting algorithm. Instead, companies may need to calibrate their hiring tools to comply with the strictest applicable laws or implement region-specific processes. For instance, if a candidate is in the EEA, GDPR and EU AI Act requirements (among others) apply to the candidate’s data even if the company is U.S.-based, which may necessitate, at a minimum, turning off purely automated rejection features for EU applicants and maintaining separate workflows and/or consent forms depending on the candidate’s jurisdiction.

Next Steps