California’s AI Revolution: Proposed CPPA Regulations Target Automated Decision Making

On November 8, 2024, the California Privacy Protection Agency (the “Agency” or the “CPPA”) Board met to discuss and commence formal rulemaking on several regulatory subjects, including California Consumer Privacy Act (“CCPA”) updates (“CCPA Updates”) and Automated Decisionmaking Technology (ADMT).

Shortly thereafter, on November 22, 2024, the CPPA published several rulemaking documents for public review and comment that recently ended February 19, 2025. If adopted, these proposed regulations will make California the next state to regulate AI at a broad and comprehensive scale, in line with Colorado’s SB 24-205, which contains similar sweeping consumer AI protections. Upon consideration of review and comments received, the CPPA Board will decide whether to adopt or further modify the regulations at a future Board meeting. This post summarizes the proposed ADMT regulations, that businesses should review closely and be prepared to act to ensure future compliance.

Article 11 of the proposed ADMT regulations outlines actions intended to increase transparency and consumers’ rights related to the application of ADMT. The proposed rules define ADMT as “any technology that processes personal information and uses computation to execute a decision, replace human decisionmaking, or substantially facilitate human decisionmaking.” The regulations further define ADMT as a technology that includes software or programs, uses the output of technology as a key factor in a human’s decisionmaking (including scoring or ranking), and includes profiling. ADMT does not include technologies that do not execute a decision, replace human decisionmaking, or substantially facilitate human decisionmaking (this includes web hosting, domain registration, networking, caching, website-loading, data storage, firewalls, anti-virus, anti-malware, spam and robocall-filtering, spellchecking, calculators, databases, spreadsheets, or similar technologies). The proposed ADMT regulations will require businesses to notify consumers about their use of ADMT, along with their rationale for its implementation. Businesses also would have to provide explanations on ADMT output in addition to a process for consumers to request to opt-out from such ADMT use.

It is important to note that the CCPA Updates will be applicable to organizations that meet the thresholds of California civil codes 1798.140(d)(1)(A), (B) and (C). These civil codes apply to organizations that: (A) make more than $25,000,000 in gross annual revenues; (B) alone or in combination, annually buy, sell, or share the personal information of 100,000 or more consumers or households; and (C) derive 50% or more of its annual revenues from selling or sharing a consumers’ personal information. While not exhaustive of the extensive rules and regulations described in the proposed CCPA Updates, the following are the notable changes and potential business obligations under the new ADMT regulations.

Scope of Use

Businesses that use ADMT for making significant decisions concerning consumers must comply with the requirements of Article 11. “Significant decisions” include decisions that affect financial or lending services, housing, insurance, education, employment, healthcare, essential goods services, or independent contracting. “Significant decisions” may also include ADMT used for extensive profiling (including, among others, profiling in work, education, or for behavioral advertising), and for specifically training AI systems that might affect significant decisions or involve profiling.

Providing a Pre-Use Notice

Businesses that use ADMT must provide consumers with a pre-use notice that informs consumers about the use of ADMT, including its purpose, how ADMT works, and their CCPA consumer rights. The notice must be easy-to-read, available in languages the business customarily provides documentation to consumers, and accessible to those with disabilities. Business must also clearly present the notice to the consumer in the way which the business primarily interacts with the consumer, and they must do so before they use any ADMT to process the consumer’s personal information. Exceptions to these requirements will apply to ADMT used for security, fraud prevention, or safety, where businesses may omit certain details.

According to Section 7220 of the CCPA Updates, pre-use notice must contain:

A plain language explanation of the business’s purpose for using ADMT.

A description of the consumer’s right to opt-out of ADMT, as well as directions for submitting an opt-out request.

A description of the consumer’s right to access ADMT, including information on how the consumer can request access the business’ ADMT.

A notice that the business may not retaliate against a consumer who exercises their rights under the CPPA.

Any additional information (via a hyperlink or other simple method), in plain language, that discusses how the ADMT works.

Consumer Opt-Out Rights

Consumers must be able to opt-out of ADMT use for significant decisions, extensive profiling, or training purposes. Exceptions to opt-out rights include where businesses use ADMT for safety, security, or fraud prevention or for admission, acceptance, or hiring decisions, so long as it is necessary, and its efficacy has been evaluated to ensure it works as intended. Businesses must provide consumers at least two methods of opting out, one of which should reflect the way the business mainly interacts with consumers (e.g., email, internet hyperlink etc.). Any opt-out method must be easy to execute and should require minimal steps that do not involve creating accounts or providing unnecessary info. Businesses must process opt-out requests within 15 business days, and they may not retaliate against consumers for opting out. Businesses must wait at least 12 months before asking consumers who have opted out of ADMT to consent again for its use.

Providing Information on the ADMT’s Output

Consumers have the right to access information about the output of a business’s ADMT. The CPPA regulations do not define “output,” but the term likely includes outcomes produced by ADMT and the key factors influencing them.

When consumers request access to ADMT, businesses must provide information on how they use the output concerning the consumer and any key parameters affecting it. If they use the output to make significant decisions about the consumer, the business must disclose the role of the output and any human involvement. For profiling, businesses must explain the output’s role in the evaluation.

Output information includes predictions, content, recommendations, and aggregate statistics. Depending on the ADMT’s purpose, intended results, and the consumer’s request, the information provided can vary. Businesses must carefully consider these nuances to avoid over-disclosure.

Human Appeal Exception

The CPPA proposes a “human appeal exception,” by which consumers may appeal a decision to a human reviewer who has the authority to overturn the ADMT decision. Business can choose to offer a human appeal exception in lieu of providing the ability to opt out when using ADMT to make a significant decision concerning access to, denial, or provision of financial or lending services, housing, insurance, education enrollment or opportunity, criminal justice, employment or independent contracting opportunities or compensation, healthcare services, or essential goods or services.

To take advantage of the human appeal exception, the business must designate a human reviewer who is able to understand the significant decision the consumer is appealing and the effects of the decision on the consumer. The human reviewer must consider the relevant information provided by the consumer in their appeal and may also consider any other relevant source of information. The business must design a method of appeal that is easy for consumers to execute, requiring minimal steps, and that it clearly describes to the consumer. Communications and disclosures with appealing consumers must be easy to read and understand, written in the applicable language, and reasonably accessible.

Risk Assessments

Under the CPPA’s proposed rules, every business that processes consumer personal information must conduct a risk assessment before initiating that processing, especially if the business is using ADMT to make significant decisions concerning a consumer or for extensive profiling. Businesses must conduct risk assessments to determine whether the risks to consumers’ privacy outweigh the benefits to consumers, the business, and other stakeholders.

When conducting a risk assessment, businesses must identify and document: the categories of personal information to be processed and whether they include sensitive personal information; the operational elements of its ADMT processing (e.g., collection methods, length of collection, number of consumers affected, parties who can access this information, etc.); the benefits that this processing provides to the business, its consumers, other stakeholders, and the public at large; the negative impacts to consumers’ privacy; the safeguards that it plans to implement to address said negative impacts; information on the risk assessment itself and those who conducted it; and whether the business will initiate the use of ADMT despite the identified risks.

A business will have 24 months from the effective date of these new regulations to submit the results of their risk assessment conducted from the effective date of these regulations to the date of submission. After completing its first submission, a business must submit subsequent risk assessments every calendar year. In addition, a business must review and update risk assessments to ensure accuracy at least once every three years, and it should convey updates through the required annual submission. If there is any material change to a business’ processing activity, it must immediately conduct a risk assessment. A business should retain all information collected of a business’ risk assessments for as long as the processing continues, or for five years after the completion of the assessment, whichever is later.

What Businesses Should Do Now

The CPPA’s proposed ADMT regulations under the CCPA emphasize the importance of transparency and consumer rights. By requiring businesses to disclose how they use ADMT outputs and the factors influencing the outputs, the regulations aim to ensure that consumers are well-informed, and safeguards exist to protect against discrimination. As businesses incorporate ADMT, including AI tools, for employment decision making, they should follow the proposed regulations’ directive to conduct adequate risk assessments. Regardless of the form in which these regulations go into effect, preparing a suitable AI governance program and risk assessment plan will protect the business’s interests and foster employee trust.

Please note that the information provided in the above summary is only a portion of the rules and regulations proposed by the CCPA Updates. Now that the comment period closed, the CPPA will deliberate and finalize the CCPA Updates within the year. Evidently, these proposed regulations will require more action by businesses to remain compliant. While waiting for the CPPA’s finalized update, it is important to use this time to plan and prepare for these regulations in advance.

CASE OF THE STOLEN LEADS?: Court Refuses to Enforce Lending Tree Lead That Was Not Transferred to the Mortgage Company That Called Plaintiff

So a loan officer at one mortgage company leaves the mortgage company he was with and seemingly steals leads and takes them to another mortgage company (maybe this was allowed, but I doubt it.)

While at the new mortgage company he sends out robocalls to the leads he obtained from the prior company–including leads submitted on leandingtree.com.

One of the call recipients sues under the TCPA claiming she had consented to receive calls from the first mortgage company but not the second because Lending Tree had only transferred the lead to the first company.

The second mortgage company–Fairway Independent Mortgage Company– moved for summary judgment in the case arguing that because it too was on the vast Lending Tree partners list, the consumer’s lead was valid for the calls placed by the LO while employed by it as well.

Well in Shakih v. Fairway, 2025 WL 692104 (N.D. Ill March , 2025) the Court determined a jury would have to decide the issue.

Although Plaintiff submitted the Lending Tree form and thereby agreed to be contacted by over 2,000 companies–including both of the mortgage companies at issue– the Lending Tree website provided the information would only be provided to five of those companies.

In the Court’s view a jury could easily determine the consumer’s agreement to provide consent was limited to only the five companies Lending Tree selected on the consumer’s behalf to receive calls– not to all 2,000 companies.

Lending Tree itself submitted a brief explaining that sharing leads between partners is not permitted, and the Court found this submission valuable in assessing the scope of the consent the consumer was presumed to have given.

The Court was also unmoved that the LO had previously spoken to the plaintiff while employed at his previous mortgage company–the mere fact that the LO changed jobs did not expand the scope of the consent that was previously given.

So like I said, absolutely fascinating case. The jury will have to sort it out and we will pay close attention to this one.

Proposed HIPAA Security Rule Updates May Significantly Impact Covered Entities and Business Associates

As we noted in our previous blog here, on January 6, 2025, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office for Civil Rights (OCR) published a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) proposing substantial revisions to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Security Rule (45 C.F.R. Parts 160 and 164) (the “Security Rule”).

This NPRM is one of several recent actions taken on the federal level to improve health data security. A redline showing the NPRM’s proposed revisions to the existing Security Rule language is available here. Comments on this NPRM must be submitted to OCR by March 7, 2025. Over 2,800 comments have been submitted thus far. These comments include opposition from several large industry groups raising concerns about the costs of compliance, asserting that the NPRM would impose an undue financial burden without a clear need for such changes to the existing framework. Some commentators expressed concerns regarding the burden on smaller or solo practitioners, while other commentators wrote in support of the effort to improve cybersecurity and commented on suggested alterations to particular elements of the rulemaking. Although the Trump administration has not apparently publicly commented on the NPRM and the final outcome of the rulemaking remains unclear, this Insight details important changes in the NPRM and potential widespread impacts on both covered entities and business associates (collectively, “Regulated Entities”).

The NPRM, if finalized as drafted, establishes new prescriptive cybersecurity and documentation requirements. This represents a significant change for a rule whose hallmark has historically been a flexible approach based upon cybersecurity risk, considering the size and complexity of an organization’s operations. Notably, the background to the NPRM is that the Security Rule already applies to Regulated Entities, including health-related information technology (IT) and artificial intelligence (AI) organizations that process health data on behalf of covered entities. The overall impact of the proposed changes may vary because certain Regulated Entities may already have in place the more robust safeguards prescribed by the NPRM. However, for those Regulated Entities that have not previously taken all such steps, including complying with the enhanced documentation requirements, the burden of the new compliance requirements may be significant.

OCR pointed to several justifications for the proposed revisions to the Security Rule, including:

the need for strong security standards in the health care industry to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the health care system;

the continuous evolution of technology since the Security Rule was last updated in 2013;

inconsistent and inadequate compliance with the Security Rule among Regulated Entities; and

the need to strengthen the Security Rule to address changes in the health care environment, including the increasing number of cybersecurity incidents resulting from a proliferation of evolving cyber threats.

Although not discussed in detail by OCR, the growing number of state privacy and data protection laws, risk management frameworks related to data protection, and court decisions have also contributed to the impetus for greater specificity in the Security Rule with its focus on protecting identifiable patient health information.

Notably, many of the substantive requirements in the NPRM are already incorporated in various guidelines and safeguards for protecting sensitive information, such as the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Cybersecurity Framework and HHS’s cybersecurity performance goals (CPGs). Voluntary compliance with these recognized guidelines has been incentivized pursuant to the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act’s 2021 amendment because a Regulated Entity that adopts “recognized security practices” is entitled to have its adoption considered by OCR in determining fines and other consequences if the agency conducts a review of the Regulated Entity’s HIPAA compliance. Accordingly, OCR noted that these standards and other similar guidelines were considered in the development of the NPRM requirements. Moreover, even if they have already implemented these practices, Regulated Entities will be faced with significantly increased administrative requirements, such as regular review and enhanced documentation requirements.

Key Proposed Changes

The NPRM includes the following key revisions:

New/Updated Definitions Clarify Electronic Systems Within the Rule’s Protections

The NPRM includes 10 new definitions and 15 changed definitions. Some of the new definitions address basic concepts that OCR had not defined previously, including “risk,” “threat,” and “vulnerability.” These definitions are not groundbreaking but will help guide Regulated Entities in establishing a more uniform standard for what they should be evaluating when considering data security.

Another change to the definitions section involves OCR’s proposed updates to defining “information systems” as well as new definitions for “electronic information system” and “relevant electronic information system.” Throughout the NPRM, OCR clarifies when all electronic information systems must abide by a rule versus only the relevant electronic information systems. In effect, each definition narrows the preceding definition, with “relevant information electronic systems” encompassing the smallest group of systems.

The NPRM defines an “electronic information system” as an “interconnected set of electronic information resources under the same direct management control that shares common functionality” and “generally includes technology assets such as hardware, software, electronic media, information and data.” Conversely, “relevant electronic information systems” are only those electronic information systems that create, receive, maintain, or transmit electronic protected health information (ePHI) or that otherwise affect the confidentiality, integrity, or availability of ePHI. The catchall phrasing broadens the definition significantly, requiring Regulated Entities to consider electronic systems they rely on that do not contain any ePHI but may affect access to and/or the confidentiality or integrity of ePHI.

“Addressable” Security Implementation Specifications Would Become “Required”

The Security Rule sets forth three categories of safeguards an organization must address: (1) physical safeguards, (2) technical safeguards, and (3) administrative safeguards. Each set of safeguards comprises a number of standards, and, beyond that, each standard consists of a number of implementation specifications, which is an additional detailed instruction for implementing a particular standard.

Currently, the Security Rule categorizes implementation specifications as either “addressable” (i.e., which give Regulated Entities flexibility in how to approach them) or “required” (i.e., they must be implemented by Regulated Entities). In meeting standards that contain addressable implementation specifications, a Regulated Entity currently has the option to (1) implement the addressable implementation specifications, (2) implement one or more alternative security measures to accomplish the same purpose, or (3) not implement either an addressable implementation specification or an alternative. In any event, the Regulated Entity’s choice and rationale must be documented.

According to the NPRM, OCR has become concerned that Regulated Entities view addressable implementation specifications as optional, thereby reducing the ultimate effectiveness of the Security Rule. The NPRM proposes to remove the distinction between “addressable” and “required” specifications, making all implementation specifications required, except for a few narrow exemptions.

Technology Asset Inventories and Information System Maps Are Required

The current Security Rule requires Regulated Entities to assess threats, vulnerabilities, and risks but stops short of prescribing particular methods or means of doing so. Certain recognized security practices generally include assessing technology assets and reviewing the movement of ePHI through technological systems to ensure there are no blatant vulnerabilities or overlooked risks.

The NPRM proposes to turn these practices into explicit requirements to create a technology asset inventory and a network map. The technology asset inventory would require written documentation identifying all technology assets, including location, the person accountable for such assets, and the version of each asset. The network map must illustrate the movement of ePHI through electronic information systems, including how ePHI enters, exits, and is accessed from outside systems. Additionally, the network map must account for the technology assets used by business associates to create, receive, maintain, or transmit ePHI. Both the technology asset inventory and network map would need to be reviewed and updated at least once every 12 months.

More Specific Risk Analysis Elements and Frequency Requirements Are Imposed

The Security Rule currently requires Regulated Entities to conduct a risk analysis assessing the potential risks and vulnerabilities to the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of ePHI held by such entities. As mentioned above, the Security Rule itself does not actually define “risk,” leaving some latitude for Regulated Entities to determine what should be included and considered in their risk analyses. While NIST (e.g., SP 800-30), the CPGs, and other authoritative sources have, over time, developed practices for conducting risk analyses, the current Security Rule (last updated in 2013) does not reflect what many now consider to be “best practices,” nor does it provide a specific methodology for Regulated Entities to consider in analyzing risks.

The NPRM imposes specific requirements that must be included in a risk analysis and its documentation, including:

a review of the aforementioned technology asset inventory and network map;

identification of all reasonably anticipated threats to the ePHI created, received, maintained, or transmitted by the Regulated Entity;

identification of potential vulnerabilities to the relevant electronic information systems of the Regulated Entity;

an assessment and documentation of the security measures the Regulated Entity uses to ensure that the measures protect the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of the ePHI;

a reasonable determination of the likelihood that “each” of the identified threats will exploit the identified vulnerabilities; and

if applicable, a reasonable determination of the potential impact of such exploitation and the risk level of each threat.

OCR notes in its preamble that there is still flexibility in determining risk based on the specific type of Regulated Entity and that entity’s specific circumstances. A high or critical risk to one Regulated Entity might be low or moderate to another. OCR is attempting to draw a fine line between telling Regulated Entities more explicitly what they should consider as risks (and what classification of risk should be assigned) while staying true to the hallmark flexibility of the Security Rule in allowing Regulated Entities to determine criticality.

The NPRM requires that risk analyses be reviewed, verified, and updated at least once every 12 months or in response to environmental or operational changes impacting ePHI. In addition to the risk analysis, the NPRM also proposes a separate evaluation standard wherein the Regulated Entity must create a written evaluation to determine whether any and all proposed changes in environment or operations would affect the confidentiality, integrity, or availability of ePHI prior to making that change.

Patch Management Is Now Subject to Mandated Timing Requirements

The NPRM proposes a new patch management standard that requires Regulated Entities to implement policies and procedures for identifying, prioritizing, and applying software patches throughout their relevant electronic information systems. The NPRM proposes specific timing requirements for patching, updating, or upgrading relevant electronic information systems based on the criticality of the patch in question:

15 calendar days for a critical risk patch,

30 calendar days for a high-risk patch, and

a reasonable and appropriate period of time based on the Regulated Entity’s policies and procedures for all other patches.

The NPRM contains limited exceptions for patch requirements where a patch is not available or would adversely impact the confidentiality, integrity, or availability of ePHI. Regulated Entities must document if/when they rely on such an exception, and they must also implement reasonable and appropriate compensating controls to address the risk until an appropriate patch becomes available.

Workforce Controls Are Tightened, Including Training and Terminating Access

The Security Rule currently has general workforce management requirements, including procedures for reviewing system activity, policies for ensuring workforce members have appropriate access, and required security awareness training. Although Regulated Entities are currently required to identify the security official responsible for the development and implementation of the security policies and technical controls, the NPRM would require the identification to be in writing.

Despite the current rules relative to workforce security, OCR noted that many Regulated Entities are not in full compliance with such requirements. OCR cited to an investigation involving unauthorized access by a former employee of a Regulated Entity as an example of Regulated Entities not tightly controlling and securing access to their systems. The NPRM addresses that issue by outlining more explicit requirements for workforce control policies, which must be written and reviewed at least once every 12 months.

In addition, the NPRM proposes strict timing requirements for workforce access and training:

Terminated employees’ access to systems must end no later than one hour after termination.

Other Regulated Entities must be notified after a change in or termination of a workforce member’s authorization to access ePHI of those other Regulated Entities no later than 24 hours after the change or termination.

New employees must receive training within 30 days of establishing access and at least once every 12 months thereafter.

Verifying Business Associate Compliance Is Required to Protect Against Supply Chain Risks

The NPRM also includes a new requirement for verifying business associate technical safeguards. Under the NPRM, Regulated Entities must obtain written verification of the technical safeguards used by business associates/subcontractors that create, maintain, or transmit ePHI on their behalf at least every 12 months. Such verification must be written by a person with appropriate knowledge of, and experience with, generally accepted cybersecurity principles and methods, which the HHS website refers to as a “subject matter expert.”

Multi-Factor Authentication and Other Technical Controls Are Mandatory

While the Security Rule has significant overlap with the NIST Cybersecurity Framework and CPGs, the NPRM would further align the Security Rule with these frameworks relative to technical controls. For example, the NPRM would require Regulated Entities to implement minimum password strength requirements that are consistent with NIST. Additionally, the NPRM proposes multi-factor authentication requirements that are consistent with the CPGs, which identify multi-factor authentication as an “essential goal” to address common cybersecurity vulnerabilities. Under the NPRM, multi-factor authentication will require verification through at least two of the following categories:

Information known by the user, such as a password or personal identification number (PIN);

Items possessed by the user, including a token or a smart identification card; and

Personal characteristics of the user, such as a fingerprint, facial recognition, gait, typing cadence, or other biometric or behavioral characteristics.

The NPRM permits limited exceptions from multifactor authentication where (1) current technology assets do not support multi-factor authentication, and the Regulated Entity implements a plan to migrate to a technology asset that does; (2) an emergency or other occurrence makes multi-factor authentication infeasible; or (3) the technology asset is a device approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Other proposed minimum technical safeguards in the NPRM include:

segregation of roles by increased privileges,

automatic logoff,

log-in attempt controls,

network segmentation,

encryption at rest and in transit,

anti-malware protection,

standard configuration for OS and software,

disable network ports,

audit trails and logging,

vulnerability scanning every six months, and

penetration testing every 12 months.

Contingency/Disaster Planning Is Required to Ensure Resiliency

The Security Rule requires contingency planning for responding to emergencies or occurrences that damage systems containing ePHI, including periodic testing and revision of those plans.

The NPRM outlines more concrete obligations relative to contingency planning, including requirements to identify critical electronic information systems. The NPRM proposes relatively short timing requirements, requiring the implementation of procedures to restore critical electronic information systems and data within 72 hours of a loss and requiring business associates to notify covered entities upon activation of their contingency plans within 24 hours after activation.

Regulated Entities are granted the ability to define what these critical electronic information systems are in conducting their criticality analysis and should consider the quick turnaround time for restoring access when making these determinations.

Impact of the Proposed Changes

Regardless of what security framework, controls, and processes Regulated Entities may already have in place, there are three areas where all organizations can expect to see a significant impact in terms of planning and implementation: (1) increased documentation burden; (2) increased compliance obligations; and (3) business associate agreements (BAAs) compliance. The compliance burden will certainly be significant (as many of the commentators have pointed out), but given the breadth of the NPRM, the full extent of the compliance burden will need to await a final resolution of the rulemaking process.

Increased Documentation Burden

While the Security Rule already requires that Regulated Entities develop and maintain security policies and procedures, the NPRM would expressly require that those policies and procedures, as well as proposed additional plans (e.g., security incident response plans), be documented in writing. As a result, if/when OCR is assessing a Regulated Entity’s compliance with the Security Rule, it will likely have a longer checklist of written policies and procedures it expects to see. In addition, the technology asset inventory, network map, written verification of technical safeguards used by business associates, and all of the analyses and evaluations required by the NPRM would need to be memorialized in writing. Many of these documents would require review at least once per year. Many Regulated Entities may find the new documentation requirements impose an increased administrative burden. Further, with respect to Regulated Entities that do not have sufficient internal expertise or resources to tackle the implementation of these proposed requirements, it is likely that Regulated Entities will need to engage third-party legal and IT experts to meet these requirements.

Increased Compliance Obligations

With the additional written policies and procedures come additional obligations to test and review those procedures. Policies cannot be established and stored away until OCR asks to review them; rather, security policies must be revisited and reviewed at least every 12 months. The NPRM also requires that some of these policies be put to the test to determine the adequacy of the procedures in place at least once every 12 months. This will require dedication of additional time and resources on an ongoing basis. Again, to meet these requirements, Regulated Entities may need to engage third-party legal and IT experts to support these efforts.

The NPRM also contains some new timing requirements that may necessitate the development and implementation of new processes to meet these tight deadlines:

A former employee’s access must end within one hour of the termination of the individual’s employment.

Business associates must report to covered entities within 24 hours of activating contingency plans.

Disaster plans must restore critical electronic information systems and data within 72 hours of a loss.

Critical and high-risk patches not exempted from the rule must be deployed within 15 and 30 days, respectively.

Business Associate Agreements Compliance

As business associates are directly regulated under the Security Rule, they will also be beholden to the enhanced requirements of the NPRM. In addition, as a result of many of the NPRM’s proposed changes, covered entities and business associates will owe one another new obligations.

As a result, it is likely that these new requirements under the NPRM will impact what is memorialized in BAAs. For example, Regulated Entities must obtain written verification from their business associates that they have implemented the required technical safeguards not only upon contracting but at least once a year thereafter. Regulated Entities should also consider revising their existing BAAs to make more explicit the security safeguard requirements that the NPRM imposes, such as multi-factor authentication and patch management. Further, in light of the potential significant changes to security obligations under the NPRM, parties may also wish to reconsider other provisions in their BAAs regarding risk allocation and indemnification rights, audit rights, third-party certification obligations, offshoring, and reporting triggers and timelines, among others. Depending on the volume of BAAs a Regulated Entity maintains, this renegotiation of BAAs could become a costly and time-consuming endeavor.

Recognition of New/Emerging Technologies

Finally, OCR acknowledged the constantly evolving nature of technology, including quantum computing, AI, and virtual and augmented reality. OCR reiterated its position that the Security Rule, as written, is meant to be technology-neutral; therefore, Regulated Entities should comply with the rule regardless of whether they are using new and emerging technologies. Nevertheless, OCR discussed how the Security Rule may apply in the case of quantum computing, AI, or virtual and augmented reality use and has included a request for information from industry stakeholders and others regarding:

whether HHS’s understanding of how the Security Rule applies to new technologies involving ePHI is not comprehensive and, if so, what issues should also be considered;

whether there are technologies that currently or in the future may harm the security and privacy of ePHI in ways that the Security Rule could not mitigate without modification, and, if so, what modifications would be required; and

whether there are additional policy or technical tools that HHS may use to address the security of ePHI in new technologies.

* * * * *

The future of the NPRM remains uncertain as to whether it will be finalized under the second Trump administration. While efforts to strengthen cybersecurity protections across the health care sector have gained bipartisan support, including under the first Trump administration, the estimated cost of compliance and heightened regulatory obligations under the NPRM may face challenges in light of the second Trump administration’s stated position against increased federal regulation.

Alaap B. Shah also contributed to this article.

China Issues Measures on Data Protection Compliance Audits

The Cyberspace Administration of China (“CAC”) recently released requirements regarding data protection audits, titled “Administrative Measures on Compliance Auditing of Personal Information Protection” (the “Measures”). The Measures will go into effect on May 1, 2025.

The Measures were promulgated in accordance with the Personal Information Protection Law (“PIPL”) and Administrative Regulations on the Security of Network Data. The Measures set forth the: (1) conditions that would trigger an audit of a data handler’s compliance with relevant personal information protection legal requirements; (2) selection of third-party compliance auditors; (3) frequency of compliance audits; and (4) obligations of data handlers and third-party auditors in conducting compliance audits. An Appendix to the Measures, titled “Guidelines on Personal Information Protection Compliance Auditing” (the “Guidelines”), contains additional compliance audit requirements.

Voluntary and Mandatory Compliance Auditing

The Measures will require data handlers that process the personal information of more than 10 million individuals to conduct compliance auditing at least once every two years.

The Measures will permit cyberspace administration and other relevant authorities to request data handlers to conduct third-party audits where:

the data handler’s processing activities pose a great risk to the rights and interests of individuals;

the data handler lacks sufficient security measures;

the data handler’s processing activities may infringe on the rights and interests of a large number of individuals; or

the data handler experiences a data breach that results in the leakage, tampering, loss or destruction of the personal information of more than one million individuals or the sensitive personal information of more than 100,000 individuals.

For the above scenarios, the data handler will need to complete a compliance audit in accordance with the Measures’ requirements and submit an audit report to the data handler’s competent authority, with any requested corrections submitted within 15 business days to the authority.

Additionally, the Measures specify that data handlers may conduct compliance audits on a voluntary basis, either internally or through the use of a third-party auditor.

Specific Requirements for Certain Types of Data Handlers

Pursuant to the Measures, data handlers processing the personal information of more than one million individuals will need to designate a person in charge of the protection of personal information (referred to herein as the “Designated Data Protection Personnel”). Data handlers providing key online platform services with a significant number of users and a complex business model will need to establish an independent organization consisting mainly of external members to monitor compliance audits.

Requirements for Third-Party Auditors and Designated Data Protection Personnel

Third-party auditors will be required to be equipped with audit staff, premises, facilities and funds appropriate to the services provided, and to protect the confidentiality of data reviewed during compliance audits. Additionally, third-party auditors will be prohibited from using subcontractors.

The Measures will prohibit data handlers from using the same third-party auditor (or its affiliates) or the Designated Data Protection Personnel to conduct compliance audits on the same subject more than three times in a row.

Guidance on Compliance Audits

The Guidance will require data handlers to evaluate the following factors in compliance audits:

the legal basis for processing the personal information;

the relevant personal information processing rules;

whether the data handler has fulfilled its individual notification obligations;

the data handler’s joint processing activities;

the vendors processing personal information on the data handler’s behalf;

whether there has been a transfer of personal information due to a merger, reorganization, separation, dissolution, bankruptcy or other reason;

whether the data handler has shared personal information with other data handlers;

whether the data handler engages in automated decision-making activities;

whether the data handler publicly publishes personal information (including instances in which the data handler obtains individuals’ consent to do so);

whether the data handler has installed surveillance devices that may be used to identify individuals in public places;

whether the data handler processes sensitive personal information;

whether the data handler processes personal information of minors under 14 years old;

whether the data handler transfers personal information outside of China;

how the data handler complies with the right to erase personal information;

how the data handler protects the rights of individuals in its processing activities;

how the data handler responds to individuals’ data protection inquiries and explains its personal information processing activities;

the data handler’s internal management policies and operating procedures;

the technical security measures the data handler has implemented to protect personal information;

the data protection education and training programs provided by the data handler to its workforce;

the performance of the Designated Data Protection Personnel;

whether the data handler conducts personal information protection impact assessment where required;

the data handler’s incident response plan and its implementation of the plan; and

for data handlers providing key online platform service with a significant number of users and a complex business model, the data handler’s social responsibility report on personal information protection.

CARU Takes Privacy Action Against Buddy AI Children’s Learning Program

The Children’s Advertising Review Unit of BBB National Programs (CARU) announced a decision involving Buddy AI, a program that touts itself as an “Early learning AI teacher.” According to CARU, which encountered Buddy AI as part of its routine monitoring efforts, the app and website did not comply with the federal Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) or CARU’s children’s privacy guidelines.

Buddy AI, which is operated by AI Buddy, Inc., is a generative AI tutor for young children. The service offers voice-based lessons to help children learn English. CARU expressed concern that Buddy AI did not provide adequate notice of its information collection and use practices, make reasonable efforts to ensure that parents were directly notified of such practices, post a prominently labeled children’s privacy policy, or obtain necessary parental consent before enrolling children in the service. CARU credited Buddy AI with addressing CARU’s concerns and making changes to its app during the course of CARU’s investigation.

ANOTHER RETAILER SUED: TCPA Lawsuit Bites Sol de Janeiro in the Bum Bum

Hello again, TCPAWorld! After a grueling 2.5 months of bar prep (phew), I’m back! It’s wonderful being in the office again and I’m excited to turn my attention back towards all things Troutman Amin (and away from certain bar subjects that shall not be named).

2025 has already been jam packed with TCPA updates, rulings, and new trends, and as I was trying to catch up, I came across a familiar brand in a sticky situation. If you frequent skincare TikTok or the revered aisles of Sephora (like I do), you likely know Sol de Janeiro (“Defendant”) as a popular body care and fragrance brand. Now personally, I wouldn’t mind a discount code or two for my next body butter purchase. However, a certain Amani Manning (“Plaintiff”) is kicking up quite a stink about text messages she claims to have received, allegedly a little too early and in violation of the TCPA.

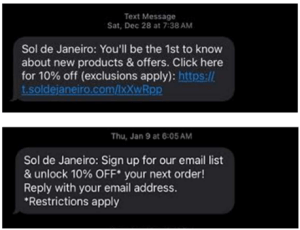

In Amani Manning v. Sol de Janeiro USA, Inc. (N.D. CA March 03, 2025), Plaintiff alleges that she received two “unauthorized” telephone solicitations from Defendant at 6:05 AM and 7:38 AM in her time zone.

Plaintiff alleges that these communications were sent in violation of TCPA’s call time limitations, which prohibit any telephone solicitation to a residential telephone subscriber before 8 a.m. or after 9 p.m. 47 C.F.R. § 64.1200(c)(1). The Complaint also states that Plaintiff’s telephone number has a California area code – presumably to counter any suggestion that she received text messages intended for a different time zone.

Plaintiff seeks to represent the following class: All persons in the United States who from four years prior to the filing of this action through the date of class certification (1) Defendant, or anyone on Defendant’s behalf, (2) placed more than one marketing text message within any 12-month period; (3) where such marketing text messages were initiated before the hour of 8 a.m. or after 9 p.m. (local time at the called party’s location).

Now as the Czar pointed out, the TCPA only restricts “telephone solicitations” to call time hours—which means calls made with consent or an established business relationship with the recipient are likely not subject to these restrictions. Interestingly, Plaintiff does not specifically allege that she did not consent to any telephone solicitations – only that she “never signed any type of authorization permitting or allowing Defendant to send them telephone solicitations before 8 am or after 9 pm.” However, the Complaint goes on to state, “If Plaintiff’s claim that Defendant routinely transmits telephone solicitations without consent is accurate, Plaintiff and the Class members will have identical claims capable of being efficiently adjudicated and administered in this case.” Confusing, but we’ll keep an eye on what happens.

In the meantime, Sol de Janeiro is just one of many retailers that have been named as defendants in recent call time lawsuits. See IN HOT WATER: Louisiana Crawfish Company Sued Over Early-Morning Text Messages – TCPAWorld, RUDE AWAKENING: Wellness Company Allegedly Sends 5:00 A.M. Texts To Consumers Without Consent. – TCPAWorld, and this one the Czar talked about just this morning: TRENDING: TCPA Class Action Against Steve Madden Shows Clear Trend of SMS Club Suits Against Retailers – TCPAWorld.

First Class Action Filed Under Washington’s MY Health MY Data Act Draws Parallels to Previous SDK Litigation

On February 10, 2025, the first class action complaint was filed pursuant to Washington’s MY Health MY Data Act (“MHMDA”), Wash. Rev. Code Ann. § 19.373.005 et seq. See Maxwell v. Amazon.com, Inc. et al., Case No. 2:25-cv-261 (W.D. Wash.). Broadly, the lawsuit alleges that, by using software development kits (“SDKs”), defendants Amazon.com, Inc. and Amazon Advertising, LLC harvested the location data of tens of millions of Americans without their consent and used that information for profit. The Complaint’s core allegations in that regard are akin to previous SDK class actions, but the MHMDA claim is new.

Software Development Kits:

The Maxwell lawsuit focuses on an SDK allegedly licensed by Amazon to a variety of mobile applications. SDKs are bundles of pre-written software code used in mobile and other applications. Many SDKs include code required in virtually every app: APIs, code samples, document libraries, and authentication tools. Rather than writing code from scratch, developers often license SDKs to streamline the app development process. In theory, SDKs allow developers to build apps in a fast and efficient manner. However, many SDKs also gather user information, including location data.

The MY Health MY Data Act:

The MHMDA came into effect on March 31, 2024, and regulates the collection and use of “consumer health data.” The term is broadly defined as personal information linked or reasonably linkable to a consumer and identifies the consumer’s physical or mental health status, including “[p]recise location information that could reasonably indicate a consumer’s attempt to acquire or receive health services or supplies.” Wash. Rev. Code Ann. § 19.373.010. Among other things, regulated entities must provide consumers with a standalone consumer health data privacy policy; adhere to consent and authorization requirements; refrain from prohibited geofencing practices; comply with valid consumer requests; and enter into certain agreements with their processors. Unlike some other relatively similar state laws, the MHMDA includes a broad private right of action.

The Complaint:

Plaintiff Cassaundra Maxwell alleges that Amazon’s SDKs, operating in the background of other applications like the Weather Channel and OfferUp apps, unlawfully obtained user location data without consumers’ knowledge or consent. More specifically, Plaintiff claims that “Amazon collected Plaintiff’s consumer health data, including biometric data and precise location information that could reasonably indicate a consumer’s attempt to acquire or receive health services or supplies” without sufficient notice or consent. Plaintiff further asserts that, once the data was harvested, Amazon used it for its own targeted advertising purposes and for sale to third parties.

Plaintiff seeks to certify a class consisting of all natural persons residing in the United States whose mobile device data was obtained by Defendants through the Amazon SDK. The Complaint includes seven purported causes of action: (1) Federal Wiretap Act violations, (2) Stored Communications Act violations, (3) Computer Fraud and Abuse Act violations, (4) Washington Consumer Protection Act violations, (5) MHMDA violations, (6) invasion of privacy, and (7) unjust enrichment.

Historical Perspective:

Despite the new MHMDA claim, the Maxwell v. Amazon Complaint is similar to those from prior SDK cases. In Greenley v. Kochava, Inc., 684 F. Supp. 3d 1024 (S.D. Cal. 2023), for example, California residents brought a putative class action alleging improper data collection and dissemination by data broker Kochava. Similar to the Maxwell case, the plaintiffs in Greenley claimed that Kochava developed and coded its SDK for data collection and embedded it in third-party apps. They claimed the SDK secretly collected app users’ data, which was then packaged by Kochava and sold to clients for advertising purposes. Much like the Maxwell litigation, the improper interception and use of location data was a focal point of the Greenley plaintiffs’ allegations. Whereas the action against Amazon relies on the MHMDA, other Washington state law, and federal statues, the Greenley plaintiffs’ claims were rooted in alleged violations of California state law, including the California Computer Data Access and Fraud Act (CDAFA), California Invasion of Privacy Act (CIPA), and California Unfair Competition Law (UCL). In Greenley, Defendants filed a motion to dismiss, arguing inter alia that Plaintiff lacked standing. The Court denied the motion, holding that, “[T]he Complaint plausibly alleges Defendant collected Plaintiff’s data” and “there is no constitutional requirement that Plaintiff demonstrate lost economic value.” Greenley v. Kochava, Inc., 684 F. Supp. 3d 1024 (S.D. Cal. 2023).

Although the facts vary, some recent cases suggest courts may still be receptive to lack of standing arguments under certain circumstances. In a class action in the Southern District of New York, plaintiff claimed Reuters unlawfully collected and disclosed IP address information. Xu v. Reuters News & Media Inc., 1:24-cv-2466 (S.D.N.Y.). Plaintiff alleged violations of the California Invasion of Privacy Act. The Court dismissed Plaintiff’s claims for lack of standing, holding that the IP address used by Plaintiff to visit Reuters’ website does not constitute sensitive or personal information. Xu v. Reuters News & Media Inc., No. 24 CIV. 2466 (PAE), 2025 WL 488501 (S.D.N.Y. Feb. 13, 2025). The Complaint included no allegations of physical, monetary, or reputational harm. The Court noted that Plaintiff did not claim he received any targeted advertising (much less that he was harmed by such advertising) or that Reuters collected sensitive or personal identifying information data that could be used to steal his identify or inflict similar harm. See also Gabrielli, v. Insider, Inc., No. 24-CV-01566 (ER), 2025 WL 522515, at *4 (S.D.N.Y. Feb. 18, 2025) (holding that, “Not only does an IP address fail to identify the actual individual user, but the geographic information that can be gleaned from the IP address is only as granular as a zip code.”)

Takeaways:

Although the Maxwell Complaint against Amazon relies on the recently enacted MHMDA, its underlying allegations largely track previous SDK claims. As states continue to enact privacy legislation granting private rights of action, businesses should expect to see SDK complaints repackaged to fit the confines of each statute. Until courts sort through these types of claims over the course of the next several years, we may see many more cases follow in Maxwell’s footsteps. Businesses, particularly those in the healthcare space, should be mindful about their use of SDKs going forward.

BACK TO BASICS: Court Dismisses Plaintiff’s TCPA Case Against Liberty Bankers On the Simplest Possible Grounds–But Its Lawyers Missed it

For anyone who wonders why it is so important to hire attorneys that know the TCPA inside and out, here is another fun example.

In Gutman v. Liberty Bankers Insurance, 2025 WL 615128 (D. N.J. Feb. 26, 2025) a court dismissed a TCPA suit after conducting its own review of the complaint and determining it was insufficient on obvious grounds.

Interestingly, however, the Defendant’s own lawyers had missed the key issues and moved to dismiss on unrelated– and irrelevant–grounds.

In other words, Defendant should have lost because it challenged the wrong issues. But the Court viewed the flaws in the case as so obvious that it could not in good conscious allow the case to proceed.

Holy moly.

In analyzing the motion the Court said the following: “As an initial matter, neither party meaningfully addresses whether the Complaint meets the elements required to plead either claim under the TCPA.”

I mean, that’s just nuts. The entire concept of a 12(b)(6) is to challenge the elements of a claim are not pleaded.

But the Court did the analysis for Liberty Bankers and determined:

The regulated technology claim fails because no allegations existed that an ATDS was used; and

The DNC claim fails because plaintiff did not allege residential usage of his phone or that he received more than one solicitation in a 12 month period.

Anyone that practices TCPA defense would have spotted those issues immediately.

But per the Court’s order the Defendant simply missed those issues and focused on the “failure” to specifically allege the dates and times of phone calls– which is never going to win as a motion to dismiss ground.

Eesh.

But either way Defendant walked away with the W and TCPAWorld walks away with a reminder– don’t expect the court to bail you out.

A Brief Reminder About the Florida Information Protection Act

According to one survey, Florida is fourth on the list of states with the most reported data breaches. No doubt, data breaches continue to be a significant risk for all business, large and small, across the U.S., including the Sunshine State. Perhaps more troubling is that class action litigation is more likely to follow a data breach. A common claim in those cases – the business did not do enough to safeguard personal information from the attack. So, Florida businesses need to know about the Florida Information Protection Act (FIPA) which mandates that certain entities implement reasonable measures to protect electronic data containing personal information.

According to a Law.com article:

The monthly average of 2023 data breach class actions was 44.5 through the end of August, up from 20.6 in 2022.

While a business may not be able to completely prevent a data breach, adopting reasonable safeguards can minimize the risk of one occurring, as well as the severity of an attack. Additionally, maintaining reasonable safeguards to protect personal information strengthens the businesses’ defensible position should it face an government agency investigation or lawsuit after an attack.

Entities Subject to FIPA

FIPA applies to a broad range of organizations, including:

• Covered Entities: This encompasses any sole proprietorship, partnership, corporation, or other legal entity that acquires, maintains, stores, or uses personal information…so, just about any business in the state. There are no exceptions for small businesses.

• Governmental Entities: Any state department, division, bureau, commission, regional planning agency, board, district, authority, agency, or other instrumentality that handles personal information.

• Third-Party Agents: Entities contracted to maintain, store, or process personal information on behalf of a covered entity or governmental entity. This means that just about any vendor or third party service provider that maintains, stores, or processes personal information for a covered entity is also covered by FIPA.

Defining “Reasonable Measures” in Florida

FIPA requires:

Each covered entity, governmental entity, or third-party agent shall take reasonable measures to protect and secure data in electronic form containing personal information.

While FIPA mandates the implementation of “reasonable measures” to protect personal information, it does not provide a specific definition, leaving room for interpretation. However, guidance can be drawn from various sources:

Industry Standards: Adhering to established cybersecurity frameworks, such as the Center for Internet Security’s Critical Security Controls, can demonstrate reasonable security practices.

Regulatory Guidance: For businesses that are more heavily regulated, such as healthcare entities, they can looked to federal and state frameworks that apply to them, such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Entities in the financial sector may be subject to both federal regulations, like the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, and state-imposed data protection requirements. The Florida Attorney General’s office may offer insights or recommendations on what constitutes reasonable measures. Here is one example, albeit not comprehensive.

Standards in Other States: Several other states have outlined more specific requirements for protecting personal information. Examples include New York and Massachusetts.

Best Practices for Implementing Reasonable Safeguards

Very often, various data security frameworks have several overlapping provisions. With that in mind, covered businesses might consider the following nonexhaustive list of best practices toward FIPA compliance. Many of the items on this list will seem obvious, even basic. But in many cases, these measures either simply have not been implemented or are not covered in written policies and procedures.

Conduct Regular Risk Assessments: Identify and evaluate potential vulnerabilities within your information systems to address emerging threats proactively.

Implement Access Controls: Restrict access to personal information to authorized personnel only, ensuring that employees have access solely to the data necessary for their roles.

Encrypt Sensitive Data: Utilize strong encryption methods for personal information both at rest and during transmission to prevent unauthorized access.

Develop and Enforce Written Data Security Policies, and Create Awareness: Establish comprehensive data protection policies and maintain them in writing. Once completed, information about relevant policies and procedures need to shared with employees, along with creating awareness about the changing risk landscape.

Maintain and Practice Incident Response Plans: Prepare and regularly update a response plan to address potential data breaches promptly and effectively, minimizing potential damages. Letting this plan sit on the shelf will have minimal impact on preparedness when facing a real data breach. It is critical to conduct tabletop and similar exercises with key members of leadership.

Regularly Update and Patch Systems: Keep all software and systems current with the latest security patches to protect against known vulnerabilities.

By diligently implementing these practices, entities can better protect personal information, comply with Florida’s legal requirements, and minimize risk.

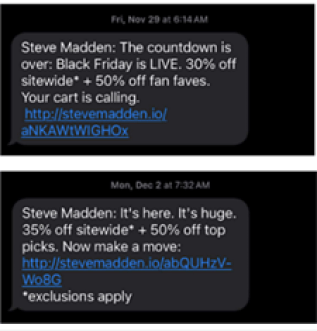

TRENDING: TCPA Class Action Against Steve Madden Shows Clear Trend of SMS Club Suits Against Retailers

Well the uptick has become a deluge and there is a very clear trend in new TCPA class actions right now. The Plaintiff’s bar–particularly our “friends” at Jibrael S. Hindi’s shop–are focused on text club messaging engagement outside of the TCPA’s timing windows.

For instance in a new suit against footwear company Steve Madden, Hindi’s client VALERIA TORRES claims she received text messages before 8 am:

As a result the Plaintiff is suing on behalf of the following class:

All persons in the United States who from four years prior tothe filing of this action through the date of class certification(1) Defendant, or anyone on Defendant’s behalf, (2) placedmore than one marketing text message within any 12-monthperiod; (3) where such marketing text messages wereinitiated before the hour of 8 a.m. or after 9 p.m. (local timeat the called party’s location).

As I have pointed out previously it is unclear whether the TCPA’s timing restrictions apply to calls and texts made with express written consent– but Hindi’s shop is apparently committed to finding out.

Will be interesting to see how this shakes out.

You can read the full complaint here: Madden Class Action

CA Legislators Charge That Privacy Agency AI Rulemaking Is Beyond Its Authority

As we have covered, the public comment period closed on February 19th for the California Privacy Protection Agency (CPPA) draft regulations on automated decision-making technology, risk assessments and cybersecurity audits under the California Consumer Privacy Act (the “Draft Regulations”). One comment that has surfaced (the CPPA has yet to publish the comments), in particular, stands out — a letter penned by 14 Assembly Members and four Senators. These legislators essentially charged the CPPA for being over its skis, calling out “the Board’s incorrect interpretation that CPPA is somehow authorized to regulate AI.”

And these lawmakers did not stop there. They questioned the Draft Regulations based on their projected costs on businesses:

While we recognize CPPA’s role in the regulatory setting, the CPPA must avoid operating in a vacuum when developing regulations. You voted to move these regulations forward with the knowledge they will cost Californians $3.5 billion in first year implementation, with ongoing costs of $1.0 billion annually for the next 10 years, and 98,000 initial job losses in California. That is nothing to say of the adverse impact on future investment and jobs noted by the analysis that will get moved to other states, or the startups that will get developed elsewhere….

It is also important to note that California could face a $2 billion deficit in 2025, as recently reported by the Legislative Analyst Office. Your votes to move these regulations forward are unlikely to help California’s fiscal condition in 2025 and, in fact, stand to make the situation much worse. We urge you to take a broader view and redraft all of your regulations to minimize its costs to Californians. Moving forward, the CPPA must work responsibly with other branches of government to get these regulations right in order to avoid significant and irreversible consequences to California. [Emphasis added.]

All of this said, it should not be construed that Privacy World disapproves of robust risk assessments as a best practice and as practically necessary for sound information governance and to ensure legal compliance. However, there is a difference between guidance and compulsion, and it seems that this debate is happening at the highest level in Sacramento, which is timely given the CPPA Board is about to select a new Executive Director to lead the CPPA. There is no doubt that California has been, and remains, the leader in consumer privacy protection, and CPPA Board and staff have the best interest of California and its citizens in mind. It is exactly these kinds of comments, however, that will help the CPPA achieve its goals and follow its mission.

Accessibility Law in Canada: Cross-Country Disability Access Legislation

Some jurisdictions in Canada are subject to accessibility legislation that sets disability access standards, such as for provincially regulated organizations operating in the provinces of Ontario and Manitoba and for federally regulated industries (such as telecommunications, transportation, etc.).

These laws generally do not provide a direct right of action for alleged violations of disability access standards. Rather, recourse is available through other legislation that prohibits discrimination on the basis of disability, including human rights legislation in every Canadian jurisdiction.

Quick Hits

Organizations that are provincially regulated in Ontario and/or Manitoba, and/or organizations that are federally regulated (e.g., telecommunications, railways, etc.) are currently subject to accessibility legislation.

Provincially regulated private-sector organizations in other Canadian provinces and territories are not currently subject to accessibility standards legislation.

For federally regulated organizations, the Accessible Canada Act (ACA) requires development of an accessibility plan in consultation with people with disabilities and annual reporting on progress. The next deadline, for private-sector organizations to file their second progress report, is June 1, 2025.

In Ontario, the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA) applies to all organizations and requires compliance reporting every three years. The next deadline is December 31, 2026.

In Manitoba, the Accessibility for Manitobans Act sets accessibility standards for all organizations. The next deadline is for meeting information and communication standards by May 1, 2025.

Provincial Accessibility Legislation

Ontario has Canada’s oldest and most fulsome accessibility legislation: the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act, 2005 (AODA). Organizations operating in Ontario are required to meet the standards set out in the AODA and its regulations. Every three years, organizations covered by the AODA must submit a report regarding their compliance to the Ontario Ministry of Seniors and Accessibility. The next reporting deadline is December 31, 2026.

Manitoba was next to enact accessibility legislation with the establishment of the Accessibility for Manitobans Act in 2013. Organizations are currently subject to accessibility standards under the legislation and were required to meet those standards for customer service in 2018 and employment in 2022.

The next deadlines are to meet the information and communication standards by May 1, 2025 (some specific public-sector organizations had earlier deadlines) and the transportation standard by January 1, 2027 (with the exception of accessibility upgrades to existing buses operated by conventional transit operators). Standards for the design of outdoor public spaces are in development.

Several other provinces have enacted accessibility legislation under which accessibility standards will or may apply to private-sector employers once established by regulation at some point in the future.

British Columbia’s Accessible British Columbia Act (2021) currently applies only to school districts, educational institutions, municipalities, health authorities, and other public-sector organizations, who were required to comply by September 1, 2024.

Saskatchewan’s Accessible Saskatchewan Act (2023) currently applies only to the government of Saskatchewan.

Accessibility legislation in New Brunswick (the 2024 Accessibility Act), Newfoundland and Labrador (2021’s An Act Respecting Accessibility in the Province), and Nova Scotia (Accessibility Act (2017)) do not yet impose accessibility standards on organizations, as regulations are still in development.

Several other provinces and territories do not have accessibility legislation at this time: Alberta, Northwest Territories, Nunavut, and Prince Edward Island.

Federal Accessibility Legislation

Notably, federally regulated organizations (e.g., telecommunications, railways, etc.) operating in any Canadian province or territory are subject to the federal Accessible Canada Act (ACA), regardless of whether the jurisdiction has separate provincial accessibility legislation.

Under the ACA, organizations are required to develop an accessibility plan that identifies barriers to accessibility in seven priority areas (including employment, the built environment, communication, information technology, procurement, design and delivery of programs and services, and transportation). Organizations are required to consult with people with disabilities in preparing their plans, which should outline the actions that are being taken to address the identified barriers.

Private-sector organizations were required to publish their first accessibility plans by June 1, 2023. Annual progress reports setting out what has been done to address the identified barriers were required to be published in June of each of the next two years (i.e., June 1, 2024) for the first progress report and June 1, 2025, for the second progress report. The following year, by June 1, 2026, organizations are required to publish a new accessibility plan, and the reporting cycle continues. Governmental organizations have their deadlines one year before private-sector organizations.