May v. Must – The Scope of Agency Permitting Review under Statutory Standards

The Law Court recently issued a decision in Eastern Maine Conservation Initiative v. Board of Environmental Protection that contains an enlightening discussion of what an agency must consider—as opposed to what an agency may consider—in issuing a permit. In so doing, it adopted an important limit on how far agencies must go in reviewing a project’s downstream impacts.

The case involved an appeal of a permit issued by the Department of Environmental Protection for an aquaculture facility. The permit, upheld by the Board of Environmental Protection, authorized construction of the aquaculture facility under the state Site Location of Development Law (Site Law) and installation of intake and outfall pipes under the Natural Resources Protection Act (NRPA).

Opponents of the project argued that the agency erroneously failed to conduct an independent assessment under NRPA of the harm that the project would cause to wildlife habitats. NRPA specifies that certain enumerated activities require a permit, including construction and dredging. These proposed activities must then meet various standards, including that the activity will not “unreasonably harm” wildlife habitat. Petitioners did not challenge the agency’s assessment of the impacts of construction and dredging; instead, they argued that the agency should have analyzed the effects of effluent discharge—an activity that is not enumerated in NRPA—on wildlife habitat.

The Law Court rejected this argument based on the plain language of NRPA. The Court concluded that only enumerated “activities” trigger agency review in an application for a permit under NRPA. Because the discharge of treated wastewater is not an enumerated activity, the Court held that the agency did not err by declining to analyze the issue in approving the permit.

Most interestingly, the Law Court went on to distinguish one of the cases relied upon by the petitioners, Hannum v. Board of Environmental Protection. In that case, the Law Court had upheld a denial of a NRPA permit for installation of a pier and floating dock. The agency had concluded that the use of the dock—not just its construction—would disturb tern and seal colonies. The Court affirmed because it concluded that the Board has the power to deny a permit based on its proposed use. In Eastern Maine Conservation Initiative, the Court distinguished the case as follows:

To be clear, in Hannum we did not say that the agency is obligated under NRPA to consider the expected effects on wildlife of the intended use of a structure or facility. Rather, Hannum held that it was within the agency’s discretion to take those impacts into consideration in evaluating compliance with the standard in [NRPA].

In the Court’s view, then, Hannum establishes that (at least in certain circumstances) DEP may consider activities other than those enumerated in NRPA. As an aside, it may be reasonable to question the holding in Hannum—after all, if NRPA specifically identifies the relevant activities whose impacts must be considered, the expressio unius est exclusio alterius canon of statutory interpretation would seem to suggest that the agency may not go any further. Regardless, Eastern Maine Conservation Initiative makes clear that Hannum only goes so far—simply because it may consider certain unenumerated activities, the agency at the very least does not have to consider unenumerated activities that may follow from NRPA-regulated conduct (and which had separately been reviewed under a different statutory scheme). This is an important limitation on the required scope of agency review for environmental permits.

Changes to Long Island Development: Oversight Through Special Use Permits

Go-To Guide:

Special use permits are becoming more common for various developments across Long Island municipalities.

These permits allow certain uses in zoning districts, subject to additional standards or conditions.

The approval process typically involves public hearings and consideration of factors like traffic, environmental impact, and community compatibility.

Municipalities aim to balance development needs with community concerns through special use permits, but the process may be time-consuming for applicants.

Long Island municipalities have been revising their zoning ordinances to address evolving community needs, environmental considerations, and intelligent development, expanding the list of uses that require special use permits. This GT Advisory explains what a special use permit is, what it entails, and analyzes the potential implications of a special use permit on future development.

In the past year, the towns of Babylon, Huntington, and Smithtown have revised, or are considering revising, their respective zoning codes to incorporate or expand special use permit requirements.

Town of Babylon – The town board revised its code to require a special use permit for recreational marijuana dispensaries.

Town of Huntington – In the Melville Town Center overlay, the town board adopted amendments to its zoning code to require a special use permit for mixed-use buildings, breweries, wineries, and similar uses. Huntington is also considering requiring a special use permit for certain warehouse uses in industrially zoned properties.

Town of Smithtown – Officials are considering amending the zoning code to require a special use permit for rail transfer stations and rail freight terminals.

A special use permit (also known as a “special permit,” “special exception,” or “conditional use permit”) is a land use approval for a use that is generally considered to be permitted in the respective zoning district subject to compliance with additional standards or conditions. The special use permit differs from a variance in that “[a] variance is an authority to a property owner to use property in a manner forbidden by the ordinance while a special [use permit] allows the property owner to put his property to a use expressly permitted by the ordinance.” North Shore Steak House, Inc. v. Board of Appeals of the Inc. Village of Thomaston, 30 N.Y.2d 238, 331 N.Y.S.2d 645 (1972). Simply put, a special use permit is an “as of right” use subject to additional conditions that ensure compatibility with the character of the surrounding community.

Throughout Long Island, special use permits are often required for religious or educational uses within a residential zone, drive-through establishments, and active recreational uses. Municipalities favor special use permits because they require a public hearing where the deciding board can ensure that the application conforms to the required standards or conditions. These standards or conditions are set forth in the local zoning ordinance and vary from municipality to municipality, but often center around traffic and parking impacts, conformity with the municipality’s comprehensive plan, environmental effects, and pedestrian safety. This provides the municipality flexibility by allowing the deciding board to consider each application on a case-by-case basis.

Oftentimes, the deciding board may waive the conditions of the special use permit. Where the board deciding the special use permit is the local planning or zoning board, under the New York State Town Law and Village Law, the governing board (typically the town board or village board of trustees) may authorize the board to waive approval conditions. As long as the board has the authority to do so, it may waive conditions if it determines the conditions, as they apply to the specific application, are not in the interest of the public health, safety, or general welfare, or inapplicable to the requested use. To make this determination, boards will often consider the application’s consistency with the local zoning code, the comprehensive plan, compatibility with surrounding uses, precedent, fairness, and – often most importantly – public input.

Regardless of whether the board decides to grant or deny the special use permit application, the decision must be based upon substantial evidence in the written record. North Shore Steak House, 30 N.Y.2d at 245. Generalized community objections, community pressure, and speculation cannot be the sole basis for denial of a special use permit. Instead, the written record must support that the special use permit’s specific negative impacts will exceed similar as-of-right uses. Robert Lee Realty Co. v. Village of Spring Valley, 61 N.Y.2d 892, 474 N.Y.S.2d 475 (1984).

Municipalities throughout Long Island face challenges as they increase reliance on special use permits. The special use permit application process requires significant time and resources – including traffic studies, civil and architectural plans, and environmental review under the State Environmental Quality Review Act. Some applicants may grow impatient and choose to abandon projects that might have economic and community benefits to the locality. As such, the reviewing agency should have the resources to ensure a speedy review so that the applicant can secure a public hearing.

Special use permits likely will remain a central land use regulation in Long Island’s future. The regulation generally provides a tool to allow municipalities to promote sustainable development and ensure compatibility with the comprehensive plan. However, municipalities should work with applicants and residents to navigate the challenges and opportunities discussed in this GT Advisory.

10 Ideas for MSHA Leaders in the Trump Administration to Consider

The Trump administration has made a number of changes to the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) already, and more are sure to come. So now is as good a time as ever to list some ideas for the new agency leadership to consider.

Quick Hits

The Trump administration has already implemented several changes to MSHA, with more expected, prompting a call for new leadership to consider ideas such as improving inspector consistency and deemphasizing noncritical safety standards.

Enhancing compliance outreach, especially for small or new mines, and advocating for rule changes are key priorities for mine operators.

To promote safety and health, MSHA should increase transparency in inspector training, issue more policy guidance, emphasize compliance assistance, manage inspector professionalism, continue issuing safety alerts, and hold all stakeholder meetings with online participation options.

Improving consistency regarding inspector interpretation of MSHA standards is at the top of many operator lists. Deemphasizing spending inspection time on standards that do not appreciably affect safety is high on the list of priorities, as well.

Yet another priority is enhancing compliance outreach for all operators—especially small or new mines. Operators may also want to advocate for certain rules to be changed.

Ten Ideas for MSHA to Explore

Mine operators will likely have many more good ideas to add to this list. Once a new assistant secretary at MSHA is in place, the mining industry should be ready to offer these suggestions—and more. Here are ten suggestions to get things rolling:

1. Establish a means via MSHA’s website for operators to submit to agency headquarters specific examples of misinterpretations of standards and other issues that occur in the field.

This will provide an opportunity for headquarters to weigh in. It will also allow headquarters to be informed directly by operators about what’s happening in the districts.

A specific occurrence may end up being resolved at the local level, but it is important for headquarters to know and track trends. This would present opportunities to enhance inspector training or issuance of guidance to operators.

2. Improve transparency and fair notice to operators by providing more information on how new and existing inspectors are being trained on the Mine Act and MSHA’s standards. This will help compliance, as well as increase the overall understanding regarding how inspectors are to apply the law.

3. MSHA should generally issue more policy guidance for new and existing standards.

4. End the growing practice of issuing citations for workplace examinations based on other violations being found in an area. MSHA’s “Program Policy Manual” states that the agency will not do this, yet it has become a common practice.

5. Increase the agency’s emphasis on compliance assistance to mine operators. This directly contributes to the agency’s mission of promoting safety and health by not only providing operators with information to help reduce exposure to hazards, but by enhancing the agency’s goodwill with operators and miners.

Such goodwill can help operators be fully receptive to the compliance assistance and lessons learned when enforcement is necessary. It can also facilitate further positive interactions with the agency that can help to improve safety.

6. As for specific standards to de-emphasize, we are not suggesting reinstating MSHA’s “Rules to Live By.” That list was largely used to justify heightened enforcement.

What we mean here is there are certain standards that are cited more than they should be given how minor the conditions typically are. Inspection time, which will be more critical given the shortage of inspectors, could be better spent if inspectors are not devoting energy to looking for things like whether switches are labeled in electrical boxes or portable extension cords have had a continuity check done.

7. MSHA needs to manage its inspector workforce to promote professionalism and good use of official time on duty. Inspectors who spend time berating the mine operator and its managers and using aggressive tactics to intimidate foremen and miners are hurting the agency’s effectiveness.

8. MSHA should continue to issue fatalgrams and other best practices alerts. The agency should provide updates on its fatal accident reports to note when citations issued in the investigation were modified or vacated.

9. MSHA’s ability to change its current final rules is constrained by the Mine Act, but there are certainly opportunities to do so without diminishing safety. Among the obvious rule changes needed are the prohibitions in MSHA’s crystalline silica rule on the use of respirators and rotation of miners for compliance.

10. On a positive note, MSHA should continue its stakeholder meetings at the district level and at the headquarters level. District-level meetings should always offer an online participation option, but not all do.

Stakeholder meetings are a great opportunity for the agency to provide updates and safety information, as well as answer questions from the audience.

Lay of the Land: Challenges to Data Center Construction—Past, Present and Future [Podcast]

In this episode of Lay of the Land, we are joined by Paul Manzer, principal and data center market leader with Navix Engineering, to explore the evolving landscape of data center construction. We dive into the unique civil engineering challenges—from site selection to due diligence—and trace the evolution of these challenges from past limitations to present-day complexities like supply chain issues and legal hurdles.

Looking ahead, we discuss future trends driven by AI and emerging technologies, examining how legal strategies and engineering innovation can address these challenges. We provide key takeaways for developers and investors, emphasizing the critical collaboration between legal and engineering teams.

Right to Work Compliance: Are UK Employers Keeping Up?

On Sunday, the government announced an extension of Right to Work (RTW) checks to businesses hiring gig economy and zero-hours workers, which we covered here. Just two days later, it released a report – an essential safeguard against illegal working.

Key Findings from the Report

Commissioned by the Home Office and conducted by Verian, the study surveyed 2,152 businesses across various industries in September 2024, with 30 follow-up interviews providing deeper insights. Here’s an overview of what it found:

High awareness, patchy understanding – While 89% of employers claim to be aware of RTW checks, far fewer understand exactly how to conduct them correctly. The biggest confusion? Rules around agency and zero-hours workers—no surprise given the recent law change!

Over-reliance on third parties – Some employers wrongly believe they can outsource RTW checks entirely. 81% of surveyed businesses using agency workers assumed recruitment agencies were responsible for conducting checks which is entirely understandable given that there is currently no legal obligation to conduct right to work checks on workers (only on employees).

Confusion over digital checks – Many employers aren’t keeping up with online verification. Despite all the available technology, 79% still rely primarily on manual methods. 37% of those surveyed use the Home Office online service and 23% use Identity Service Providers (IDSPs).

Compliance is inconsistent – Many businesses fail to check the right documents, exposing themselves to risk if audited.

Small businesses struggle the most – Larger firms with dedicated HR teams tend to have better compliance, whereas SMEs often lack the resources or expertise. Alarmingly, 62% of micro and small employers incorrectly believed a driving licence was a valid RTW document, compared to 42% of medium and large sponsors.

The Construction industry is at greater risk of non-compliance – Employers in construction showed the biggest knowledge gaps around acceptable RTW documents and re-checks. 41% of surveyed businesses in the sector believed illegal working was common.

Employers prioritise compliance but for different reasons – When asked why they conduct RTW checks, 91% cited preventing illegal working, 88% were focused on avoiding penalties (basically the same thing) and a very wholesome 87% said they were simply “doing the right thing”.

What’s at Stake?

Failing to meet RTW obligations can have serious consequences, including:

Fines of up to £60,000 per illegal worker (tripled from £20,000 in 2024).

Criminal liability for knowingly hiring workers who do not have the right to work (or having reasonable grounds to believe that is the case)

Reputational damage, including bad press and loss of contracts. Both public and private procurement functions are increasingly hot on this sort of thing.

Sponsorship licence risks—non-compliance could lead to licence revocation, forcing businesses to dismiss sponsored workers and preventing them from obtaining more.

How Can Employers Improve Compliance?

With the Home Office tightening enforcement, businesses need to take a proactive approach:

Review and update policies – Ensure internal HR teams understand the latest RTW check guidance and use digital verification tools correctly.

Train staff regularly – Many compliance failures result from human error. Providing ongoing training helps prevent costly mistakes.

Conduct audits – Regularly reviewing RTW records can help spot gaps and correct issues before a Home Office audit.

Use the right tech – Employers should use the Home Office’s online RTW service where applicable and ensure all checks follow the statutory excuse process.

Keep clear records – Retaining copies of RTW documents is essential for proving compliance.

The report makes it clear that while most UK employers fully intend to comply with RTW requirements, many fall short on execution. As penalties rise, businesses hiring zero-hours workers—particularly in construction, hospitality and healthcare—must ensure they fully understand RTW obligations. A small investment in compliance today could prevent huge financial and legal headaches down the line. Regrettably, it appears that the government has not taken this clear evidence that employers can fail to follow all the current regulations despite their best efforts to do so as a cue to simplify the relevant law, but instead as a reason to add further layers of complexity to it. Dumping the minefield which is worker status on top of the existing morass of rules can only end in tears before bedtime.

Why School Districts Should Consult With Legal Counsel Before Signing a Standard AIA Contract

Numerous school referenda were approved in the 2025 Spring election this week, and construction is now on the horizon. Let’s consider the contracts that will become the foundation of these building projects.

The American Institute of Architects (AIA) provides a comprehensive suite of contracts designed to streamline the creation and management of construction agreements. While these forms are expertly crafted to anticipate challenges in construction projects, they are primarily tailored for commercial use rather than for governmental entities such as school districts. As a result, AIA contracts may not fully address the unique legal and regulatory considerations school districts must navigate when undertaking construction projects. To ensure compliance with state laws and to safeguard their interests, school districts should carefully review and modify these contracts as necessary. Most importantly, school districts should consult their legal counsel before executing any construction or design contract to ensure it aligns with their specific requirements and legal obligations.

It’s important to note that any unrevised AIA contract is essentially a base form and represents just the beginning of the drafting process. Created by an association that represents architects, these agreements require careful review and revision by the school district’s counsel so that the interests of the owner-district are also incorporated. Representation by counsel during the development of the contract documents contributes toward ensuring a more balanced agreement that protects the district’s interests. This is crucial in creating a fair and equitable contractual relationship among the parties.

No standard form can perfectly accommodate every project. Each construction project and each school construction project are unique. A contract that works for one project or district may require modifications to suit the specific needs of another. Thorough review and customization are essential to ensure that AIA construction and design contracts align with the district’s wishes, requirements and legal obligations.

AIA construction contracts typically include the architect’s agreement, the contractor’s contract, and the general conditions, all of which must be consistent with one another. A common mistake is revising one of these agreements without carefully reviewing the other two documents, potentially creating conflicts between provisions.

Revisions to the base agreements might include inserting provisions that address critical steps occurring during a pre-referendum phase of a project. For instance, the parties may agree to add contract terms that reflect the contractor’s commitment to provide referendum support services such as contributing to strategy development, research, community engagement, and/or graphic design, copywriting, and editing of referendum materials. Moreover, the construction contract should be modified to require strict adherence to the plans and specifications while granting the district’s facility manager the right to observe the work during any phase of construction. The contract should include a warranty ensuring high-quality craftsmanship and materials that meet required standards. Provisions should also be added to minimize disruption to school operations and to enforce compliance with the district’s or the school’s access policy during construction.

Similarly, the design agreement should clearly outline the school district’s expectations for conceptual design, allow the facility manager opportunities to review the design, require the designer to incorporate all legal requirements, and define the designer’s responsibility for inspecting the work. Finally, it is up to the school district to establish the insurance requirements in the contracts. AIA documents do not specify coverage amounts, as these figures must be determined based on the specific project needs and on the guidance of the district’s insurance broker.

It has been the intention of this update to shed light on some of the reasons why consulting an experienced construction law attorney is invaluable when a district begins the process of contract review and development. While AIA contracts are widely recognized as the industry standard for construction agreements, these agreements should be improved upon to best serve the interests of the school district and to level the playing field between all parties.

Yes, Damages for Delay: Court Permits Delay Damage Claim to Proceed

A federal court in upstate New York is permitting a subcontractor’s delay claim to proceed notwithstanding a “no damages for delay” provision in the subcontract. The case, The Pike Company, Inc. v. Tri-Krete, Ltd., involves delay claims asserted by a subcontractor hired to install pre-cast concrete walls on a college dormitory project. The subcontractor alleges that the general contractor, The Pike Company, actively interfered with its work causing it to incur costs to overcome that interference and mitigate delays. Pike moved for summary judgment based on the no damages for delay provision in the subcontract, which generally provided that (1) the subcontractor’s only remedy for delays caused by an act or omission of the contractor was an extension of the schedule and (2) any damages for delay, interference, or changes in sequence were waived.

The court held that while such clauses are generally valid and enforceable, there are a number of recognized exceptions:

Yet there are exceptions to the general enforceability of a no damages for delay provision. Even when a contract includes such a provision, damages may be recovered for: (1) delays caused by the contractee’s bad faith or its willful, malicious, or grossly negligent conduct, (2) uncontemplated delays, (3) delays so unreasonable that they constitute an intentional abandonment of the contract by the contractee, and (4) delays resulting from the contractee’s breach of a fundamental obligation of the contract. For example, the failure of a contractor to supervise and coordinate the work of subcontractors on a construction site may preclude the enforcement of a no damages for delay provision. Likewise, a no damages for delay provision may be found to be unenforceable where there is an “intentional abandonment” of the contract that renders it unenforceable—such as when an owner makes dramatic changes to the work or causes significant delay. As the party seeking to preclude the enforcement of the no damages for delay provision, [the subcontractor] bears the “heavy burden” of demonstrating that the provision does not apply.

Applying this law to the facts at hand, the court held that evidence in the record supported a finding that one or more of these exceptions applied. This included evidence that Pike interfered with the subcontractor’s means and method of production, failed to timely complete predecessor work, compressed the subcontractor’s schedule by a factor of 50%, and refused to grant time extensions as provided for in the subcontract. Such evidence of uncontemplated and unreasonable delays caused by Pike, and Pike’s breach of its fundamental subcontract obligations, precluded summary judgment in Pike’s favor.

The court also rejected Pike’s argument that the subcontractor failed to give adequate written notice of its delay claims. The court held that under New York law, oral directives may sustain a claim for extra work damages notwithstanding a contractual provision requiring written authorization. The court further held that Pike arguably waived the written notice requirement when it granted change orders to another contractor on the same job without insisting on written notice. The issues created genuine issues of material fact that precluded summary judgment in Pike’s favor.

A copy of the court’s decision can be found here. No trial date has been set.

Listen To This Article

Pedestrian Fatalities Up Almost Half from a Decade Ago

During the first half of 2024, drivers killed 3,304 pedestrians in the United States, a 2.6% decrease from the same period in 2023, according to a new study from the Governors Highway Safety Association (GHSA). However, this decline does not overshadow the alarming trend of rising pedestrian fatalities over the past decade, which have increased by 48% since 2014, translating to 1,072 more deaths.

Pedestrian Fatality Trends

Each year, the GHSA releases the first comprehensive look at pedestrian traffic death trends for the first six months of the year, using preliminary data from State Highway Safety Offices (SHSOs). The analysis indicates that while pedestrian fatalities decreased slightly from last year, they remain 12% higher than in 2019, emphasizing a concerning trajectory for road safety.

The slight decrease in pedestrian fatalities in early 2024 aligns with a broader trend in overall traffic deaths. According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), total roadway fatalities dropped 3.2% during the first half of 2023. Nevertheless, the overall numbers remain significantly higher than those recorded five and ten years ago. In the first half of 2024, there were 18,720 roadway deaths, showing a 10% increase from 17,025 in the same period of 2019 and a 25% rise from 15,035 in 2014.

At the state level, the GHSA report reveals mixed results: pedestrian fatalities decreased in 22 states, while 23 states and the District of Columbia (D.C.) saw increases. Five states reported no change in their numbers. Notably, seven states experienced consecutive decreases in pedestrian fatalities, whereas four states faced two significant increases.

Why Are Roads So Dangerous for Pedestrians?

There is a combination of factors contributing to this rising danger for pedestrians. A decline in traffic enforcement since 2020 has allowed dangerous driving behaviors—such as speeding, distracted driving, and driving under the influence—to grow rapidly. Additionally, many roadways are designed primarily for fast-moving vehicles, often neglecting the needs of pedestrians. Many communities lack infrastructure – such as missing sidewalks and poorly lit crosswalks – that also help protect pedestrians. Furthermore, the growing presence of larger, heavier vehicles on roads increases the risk of severe injuries or fatalities in pedestrian accidents.

What Can Be Done?

To tackle this pedestrian safety crisis, the GHSA advocates for an approach that establishes a strong safety net that can protect everyone on the road. A crucial part of this strategy is traffic enforcement focused on dangerous driving behaviors – like speeding, and impaired or distracted driving – that disproportionately endanger pedestrians.

In summary, while there are signs of progress in addressing pedestrian safety, the statistics reveal a pressing need for ongoing efforts to protect those who walk on our roads. By strengthening enforcement, improving infrastructure, and promoting safe practices among both drivers and pedestrians, we can work toward reversing this tragic trend and ensuring safer streets for everyone.

Mistake No. 9 of the Top 10 Horrible, No-Good Mistakes Construction Lawyers Make: Screwing Up the Hearing Exhibits

I have practiced law for 40 years with the vast majority as a “construction” lawyer. I have seen great… and bad… construction lawyering, both when representing a party and when serving over 300 times as a mediator or arbitrator in construction disputes. I have made my share of mistakes and learned from my mistakes. I was lucky enough to have great construction lawyer mentors to lean on and learn from, so I try to be a good mentor to young construction lawyers. Becoming a great and successful construction lawyer is challenging, but the rewards are many. The following is No. 9 of the top 10 mistakes I have seen construction lawyers make, and yes, I have been guilty of making this same mistake.

While the legal profession has come a long way as far as being “paperless,” with few exceptions, construction legal disputes still maintain a high level of tree killing. To be clear, clients have moved on and are at the forefront, using AI as well as project specific software (like Procore) to manage the enormous amount of documentation necessary to timely and properly design and build large projects. While I have served on a few arbitration panels where all sides cooperate and have presented exhibits exclusively via thumb drives/laptops and links, these are the exceptions and not the rule. Last year, I was on a panel for a three-week arbitration involving six parties (owner, architect, prime contractor, surety, two subcontractors). Despite pre-hearing admonitions by the panel for counsel to work cooperatively on joint exhibits, clearly labeled and numbered, the parties presented each panel member with a total of 60 black exhibit books, each more than six inches thick… and 75% of the exhibits in each side’s set were exactly the same. Precious time was wasted during the hearing dealing with redundant and poorly organized exhibits and caused a lot of confusion. A typical exchange went something like this: “Panel, please go to our Exhibit Book 23, exhibit 235, and sorry, this exhibit has 45 pages that are not numbered, so go somewhere in the middle.” Counsel and the arbitrators would then stand up, reach back to their exhibit book stack, sort through and find the right numbered book, haul it back to the table, move (or step over) the five books they just used, pull open the book with the three-hole binder (which typically gets broken), and try to find the referenced exhibit.

There’s a better way, and before the construction lawyers out there grind their teeth and shake their heads, please remember that your goal as an advocate is to persuade the arbitrator of the merits of your client’s position. Anything you can do to make the arbitrator’s decision easier (yes, treat your arbitrator like Santa) should be done. Here are just a few of the ways – some easy, some hard – that have been implemented to address this issue, especially in large, multi-week arbitrations, with hundreds of exhibits and scores of witnesses:

Go fully or even partially paperless.

This takes full cooperation and coordination with not only counsel, but the arbitrator (who may still want hard copies). Technology is great until it is not. Is the hearing room appropriate and has the necessary technology? Of course, no need to worry about a room if it is a 100% virtual arbitration (which happened many times during COVID). But, what’s plan B if something goes wrong? Chaos happens, and that’s no good especially if it happens to you (and thus your client).

Create a joint set of exhibits.

Most good arbitrators mandate in the initial scheduling order that counsel exchange a list of all possible exhibits 30 days prior to the hearings and then work together in good faith (yes, I know that can be hard) to create a joint set of exhibit books. As mentioned above, if each side prepares and brings its own set of exhibit books, it is certain that many, if not most, of the exhibits in each sides’ books will be identical. Avoiding duplication is really easier than you think. The books can be organized in sections with a joint index. By way of example: pre-hearing briefs; contracts; pay applications, pictures/videos, damages backup, summaries, specifications, expert reports; and a year-by-year chronology (notice letters and emails). Remember that generally the technical rules of evidence do not strictly apply in arbitrations, so there is no need to fight about relevancy or admissibility. Absent something unusual, all the submitted exhibits from all sides will be admitted by the arbitrator. While this process can take time and effort, setting aside the fact that it will make the arbitrator’s life easier (especially during the post-hearing award process), it has enormous benefits, including making the preparation of witnesses and examinations so much easier and more efficient. If you try it, you will like it. If the arbitrator does not suggest this process during the initial call, you should do so.

Identify the exhibit books you will be using before an examination.

Do not wait until you begin a witness examination (direct or cross) to specify which book you will be using. Tell the arbitrator (and counsel) before you start which books you will be using so everyone can pull out those books and better follow your examination. Again, this eliminates all sides going back and forth to find the applicable witness books.

Consider creating witness exhibit books.

This may seem counterintuitive if the goals is to limit the number of books, but if you have a witness with a small number of exhibits that are scattered among multiple books, consider putting together an exhibit book for that witness that has the exhibits already numbered (as well as what books they are in).

Color code the exhibit books on the front and the spine.

Most counsel use the same black exhibit books. While there may be a label on the front and sometimes the spine, especially if there are multiple books, there can be confusion and time wasted. Using a different color code on the labels, or even different color binders, can help efficiency (“Please go to book 5, the red one.”).

Make sure each page in each exhibit is numbered.

While many of the exhibits will have their own numbers, confusion and delay occur when, for instance, there is an exhibit that has 20-60 pages, but the individual pages are not numbered. This happens with photos, long text streams and multiple invoices. There is nothing more frustrating for an arbitrator (and a witness), and it disrupts an examination, for the lawyer to say: “Please turn to book 18, exhibit 135, and if you go about ¼ of the way in, you will see a picture that looks like…” And no one can find it. Worse, halfway through your “Perry Mason-like” cross examination about that picture, the arbitrator says “Counsel, sorry, I must have been looking at the wrong picture. Can you orient me?”

Make good decisions on what exhibits go into your books, and keep up with what exhibits have been used in the hearing.

The arbitrator understands that since there is limited pre-hearing discovery in most arbitrations (sometimes no depositions), the tendency is to include every possible document or email. But be careful not to dump scores of exhibits into books that may not even be used. This will impact your credibility. And pay close attention to what exhibits are actually used during the hearing. It may be (again, treat your arbitrator like Santa) that with everyone’s cooperation, there can be scores of exhibits removed from books, or even complete books can be withdrawn.

When there will be multiple exhibit books, these simple guidelines will help you, your client, and witnesses better prepare and present your case. You can enhance your credibility by using these tactics regarding exhibits prior to your next arbitration hearing.

What Is DMSMS and What to Do About It?

What does DMSMS mean?

DMSMS stands for Diminishing Manufacturing Sources and Material Shortages. It is the loss or impending loss of manufacturers or suppliers of items, raw materials, or software. In other words, DMSMS is obsolescence. DMSMS occurs when companies (at any level of the supply chain) that make products, raw materials, or software stop doing so or are about to stop. DMSMS issues can occur for various reasons, such as technological advancements, shifts in market demand, regulatory changes, or a manufacturer’s strategic business decision.

Where can contractors find DMSMS requirements?

DMSMS requirements are typically found in prime contracts. Specifically, a Statement of Work (“SOW”) can describe DMSMS requirements such as: a DMSMS Management Plan, a Bill of Materials, Health Status Reports, End of Life Notices, and various other requirements to mitigate DMSMS risks. The contract may use Contract Data Requirements Lists (“CDRLs”) to specify the content of deliverables, the inspection and acceptance process, and the frequency of delivery (e.g., the Contractor must deliver a Health Status Report “monthly” or an End of Life Notice “as required”).

Below are descriptions of these DMSMS concepts:

A DMSMS management plan is a comprehensive strategy that outlines the processes, roles, responsibilities, and tools necessary to proactively identify, assess, and mitigate the risks associated with the loss or impending loss of manufacturers or suppliers of critical items, raw materials, or software throughout the life cycle of a system.

A Bill of Materials is a comprehensive list of materials, components, and assemblies required to construct, manufacture, or repair a product, often presented in either a flat or indentured format to show the relationships and hierarchy of the items.

A Health Status Report provides a comprehensive accounting of specific obsolescence issues within a system and identifies estimated obsolescence dates, usage rates, and stocks on hand for each item.

An End of Life Notice provides the part numbers, descriptions, and manufacturers for all items that are approaching or have reached a point when the item will no longer be produced, supported, or maintained by its manufacturer.

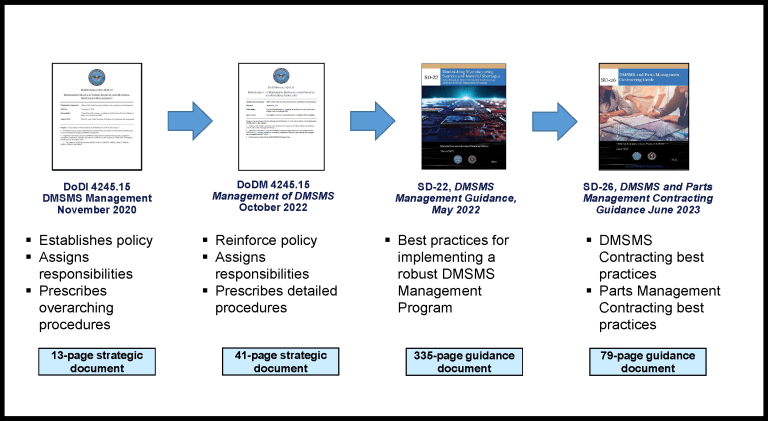

What are the important DMSMS resources?

Below are key policies on DMSMS that also include recommended contract language:

1 – Source: Robin Brown, Under Secretary of Defense Research & Engineering, DMSMS & Parts Management Program (Apr. 23, 2024) (ndia.dtic.mil/wp-content/uploads/2024/dla/Tue_Breakout_DMSMS_PMP.pdf).

DoD Instruction 4140.01 Vol. 3 recommends 18 potential courses of action for the Department of Defense (“DOD”) to consider when trying to resolve DMSMS issues, such as encouraging the existing source to continue production, making a life of type buy, converting design specifications to performance-based specifications, etc.

What risks does DMSMS pose to contractors?

Increased Costs: Contractors may need to invest in managing DMSMS risks and finding alternative sources, redesigning components, or making a life of type buy to ensure the availability of critical items. These activities can be expensive and, depending on the contractual language, may not be covered by the contract, leading to financial strain.

Compliance Risks: Contractors must comply with contract terms related to DMSMS and other terms such as qualified baselines and source of origin for parts. Failure to adhere to these requirements can result in legal and financial penalties. For example, the use of non-compliant materials or failure to report DMSMS issues can lead to contract termination or other legal actions.

Schedule Delays: DMSMS issues can cause significant schedule delays and disrupt production timelines due to the time required to identify, qualify, and implement alternative solutions.

Quality and Reliability Concerns: The use of alternative parts or materials can introduce quality and reliability concerns. For example, counterfeit parts or parts that do not meet the original specifications can compromise the performance and safety of the system. This can result in increased maintenance costs, reduced system reliability, and potential safety hazards.

Strained Customer Relationships: DMSMS can significantly strain a contractor’s relationship with its government customer. DMSMS issues can lead to increased costs, contract non-compliances, schedule delays, and quality concerns. The government purchasing command has its own customer, the warfighter, and contractors that fail to perform as required can strain that purchasing command’s relationship with the warfighter, leading to further reputational harm if the contractor is blamed for negative impacts to the warfighter.

What should contractors do to mitigate DMSMS risks?

Identify all prime contract requirements that need to be flowed down to meet prime contract terms.

Establish subcontract terms up front that will mitigate DMSMS risk such as recurring parts forecasting updates, licensing with the Original Equipment Manufacturers for access to Bills of Materials, using external data sources to identify predicted level of obsolescence risk for supplies, and developing interchangeability Parts Lists.

Negotiate terms so that if a supplier will no longer manufacture a part, they will license sufficient intellectual property (“IP”) for another source to manufacture the part. This should include the IP for necessary tooling.

Establish subcontract terms defining the party responsible for cost increases due to DMSMS issues.

Negotiate advance notice terms regarding parts availability such as requiring the supplier to provide a Last Time Buy Notice months prior to discontinuation of the product.

Request information regarding DMSMS as part of the supplier selection process.

Collaborate with customers and higher-tier suppliers through proactive risk identification and resolution, regular reviews and updates, and effective communication.

Boosting Boston’s Housing: City & State Partner to Overcome Market Challenges

According to recent news coverage, about 30,000 housing units proposed for Boston are approved by the Boston Planning Department (BPD) yet unable to break ground due to market conditions. In response, the Wu administration, in partnership with the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is advancing the following strategies to facilitate construction commencement: revising affordable housing agreements, providing direct public funding through a newly launched fund, and granting tax abatements, tax credits, and grants for office-to-residential conversions.

Revised Affordability

The Inclusionary Development Policy (IDP) originally created by a mayoral executive order in 2000, and now codified in Article 79 of the Boston Zoning Code, requires developers of market-rate housing projects to include a prescribed number of income-restricted housing units at prescribed affordability levels. The BPD prefers on-site IDP units, although compliance may be achieved by creating off-site units near the project or by paying into an IDP fund in an amount based on the project’s location in a high, medium, or low property value zone.

For stalled projects, the BPD and the Mayor’s Office of Housing (MOH) have been willing in certain circumstances to revise a project’s IDP commitments given the difficult financial environment and the urgency to build more housing. This strategy is not part of a formal program and does not follow rigid procedural rules.

Examples of recent proposals include:

A payment in lieu of half of the approved on-site IDP units based on the applicable property value zone and conditioned on building permit issuance within a specified timeframe, with the contributed amount being directed to an identified nearby affordable housing project; and

A commitment to deliver 4% instead of 18% on-site IDP units in an initial building, and to construct a separate project in close proximity with larger, more deeply affordable units, funded with proceeds from the sale or refinancing of the initial building.

In each case, affordable housing agreements with MOH were amended with a limited administrative process.

Momentum and Accelerator Funds

MassHousing is administering a newly created Momentum Fund, supplemented for Boston projects by the City of Boston’s Accelerator Fund, providing additional equity alongside private equity to improve the economics of stalled projects. The resulting noncontrolling investment would:

Comprise a quarter to half of the total ownership interests;

Be committed before construction financing closes;

Be funded when permanent financing closes; and

Be coterminous with the project’s senior loan up to 15 years.

The Momentum Fund is capitalized with $50 million as part of the Affordable Homes Act signed by Governor Healey in August 2024, and the Accelerator Fund is capitalized with $110 million proposed by Mayor Wu and approved by the Boston City Council in January 2025. MassHousing will review applications and handle underwriting, and will consult with the BPD on applications for projects in Boston.

To receive funds, projects must create at least 50 net new housing units, at least 20% of them income restricted at 80% AMI, and must demonstrate that they are energy code compliant and can commence construction within 6 months of the commitment of funds.

Resources for Office to Residential Conversions

Boston’s Downtown Residential Conversion Incentive Program supports downtown office-to-residential conversions in light of the post-pandemic decline in office utilization paired with businesses vacating Class B and C properties in favor of Class A properties. Eligible proposed conversions must be IDP and energy code compliant, and must commit to commence construction by December 31, 2026.

Developers under this program can obtain tax abatements of up to 75% at the standard residential tax rate for up to 29 years as memorialized in a Payment in Lieu of Taxes (PILOT) agreement, along with fast-tracked project impact review and reduced mitigation and public benefit commitments.

By the end of last year, 14 submitted applications to the Conversion Program representing 690 housing units resulted in 4 project approvals, with submissions and approvals continuing this year based on an extension of the program through December 2025.

Separately, the Commonwealth’s Affordable Housing Trust Fund has allocated a total of $15 million for grants to conversion projects of at least 70,000 square feet. This fund can provide up to $215,000 per affordable unit and up to a total of $4 million per project. The City of Boston will apply to the state for such funding on behalf of qualifying project applicants. As of early March 2025, about $7.5 million of the original pool is still available. In addition, the Affordable Homes Act establishes a tax credit program for qualified conversion projects covering up to 10% of total development cost to be administered by the Executive Office of Housing and Livable Communities (“EOHLC”). EOHLC is currently developing guidelines for implementation and is seeking input from developers and other interested parties.

An Unanticipated Complication of Investing in SFR: Investors Sometimes End Up Being HOA Managers

Build-to-Rent (“BTR”) is a subsector of Single Family Rentals (“SFR”). As a subsector of SFR, BTR occupies a unique space within the U.S. residential rental market. The broader category of SFR includes scattered homes for rent, while BTR communities are entire neighborhoods of new homes being rented instead of sold to homebuyers.

Traditional homebuilders are making their way into the SFR market through their BTR communities. Rather than building homes and selling them as soon as they are completed, many homebuilders have adopted a different strategy. They are holding the homes after completion and renting them. For homebuilders, BTR presents an alternative revenue stream that may provide some protection from the cyclical fluctuations of the traditional homebuilding market. This diversification has insulated some homebuilders from slowed sales in the last two years due to higher mortgage rates. This is good news for shareholders in the publicly traded homebuilders, and also for the tenants in the brand new homes who otherwise could not qualify for or afford to buy a new home.

Additionally, some institutional investors are buying entire communities in one transaction. Both scenarios result in the institutional investor having control of the applicable HOA. Some investors operate their SFR communities like multi-family rental projects whereby the homes are not built on separately platted lots but are constructed on one large lot that can only be conveyed as one property. The norm, however, is that rental homes are individually transferrable lots within community associations. When one entity owns all of the lots within a community association, the need to operate the community association in accordance with its governing documents may be questioned. It is my position that there are benefits to institutional owners in keeping community associations operative and in retaining the expertise of common interest development (aka HOA) experts.

In some neighborhoods, the development and permitting process included a requirement by the municipality that a community association must be formed to maintain shared facilities such as private streets or drainage facilities. In those cases, local law requires that the community association remain active and conduct the required maintenance.

Some communities have common area amenities shared by the residents which are often owned by the community association. If an institutional owner who owns all of the homes does not keep the association’s corporate status active and compliant, there may be title issues with the ownership of the shared amenities. Without an active association, it may not be possible to insure the common amenities.

Additionally, for the institutional owner there is liability protection in the association owning amenities like a swimming pool, tennis courts, or a fitness center. In the event of an injury on those amenities, the association would be the liable property owner, not the institutional owner. This serves to limit liability to the assets of the association, while protecting those of the institutional owner.

The institutional owner may find operating an association burdensome because state laws vary widely and there are many corporate governance laws that apply to community associations differently than other types of business entities. Therefore, institutional investors should consider retaining HOA managers to exclusively handle HOA-related issues within their communities. Such managers have different knowledge and skill sets than the leasing or property managers that might otherwise be engaged by an institutional owner in the operation of a rental community.

Additionally, attorneys who specialize in HOA law and have regional expertise can provide benefit to institutional owners. When an institutional owner owns an entire community, HOA counsel can ensure compliance with niche laws. If you have any questions or would like more information on this subject, please feel free to get in touch with the author of this article.