CTA Interim Final Rule Eliminates Requirements for U.S. Companies and U.S. Individuals to File Beneficial Ownership Reports

On March 26, 2025, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), in an action that was promised earlier in March, issued an interim final rule (the “Interim Rule”) that removes all requirements for U.S. companies and U.S. individuals to report beneficial ownership information (BOI) under the Corporate Transparency Act (CTA).

Specifically, the Interim Rule eliminates all BOI reporting requirements under the CTA for:

all entities that are formed in the United States, and

U.S. individuals who are beneficial owners of any entity, including those entities that were formed under the laws of a foreign country.

In its press release announcing the Interim Rule, FinCEN explains that the Interim Rule narrows the definition of a “reporting company” to include only those entities that are formed under the laws of a foreign country and have registered to do business in any U.S. state or Tribal jurisdiction (i.e., entities that were previously defined under the CTA as “foreign reporting companies”).

Those entities that were previously defined under the CTA as “domestic reporting companies” are now expressly exempt from BOI reporting requirements under the Interim Rule.

Foreign companies that meet the new definition of a “reporting company” under the CTA are required to report their BOI to FinCEN unless one or more of the existing reporting exemptions applies to them. Additionally, any reporting company that is required to make a filing under the CTA is no longer required to report any U.S. persons as beneficial owners, and such U.S. persons are not required to report BOI with respect to any such company.

FinCEN further announced that the new BOI filing deadline for any reporting companies established before March 26, 2025, will be April 25, 2025. Reporting companies that register to do business in the United States on or after March 26, 2025, must file an initial BOI report no later than 30 calendar days after receiving notice from the secretary of state (or similar office) that the company’s registration to do business is effective.

FinCEN has also published questions and answers (Q&As) to provide additional explanatory information on BOI reporting in light of the Interim Rule. Among the information included in the Q&As is that FinCEN is accepting comments on this Interim Rule until May 27, 2025, and that it will finalize the Interim Rule later this year.

We will continue to monitor additional developments regarding the CTA, including any changes that may arise during the comment period before the Interim Rule is finalized.

FinCEN Exempts U.S. Entities from Reporting, but Uncertainty Remains

On March 21, 2025, the previous deadline to report Beneficial Ownership Information (BOI) to the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) under the Corporate Transparency Act (CTA), FinCEN released an interim final rule removing this requirement for U.S. companies. While U.S. companies are no longer required to report BOI under this rule, questions remain over the implementation of the CTA and the possibility that reporting for domestic companies may be reinstated.

The Interim Rule’s Impact

The interim final rule exempts domestic reporting companies and their beneficial owners from a requirement to report BOI to FinCEN by excluding domestic companies from the scope of the term “reporting company.” Under the new rule, a reporting company only includes an entity that is (a) a corporation, limited liability company, or other entity; (b) formed under the law of a foreign country; and (c) registered to do business in the United States. The rule also clarifies that foreign entities are exempt from reporting BOI about any beneficial owner who is a U.S. person.

Accordingly, U.S. entities are not required to file BOI reports, regardless of whether they have U.S. or foreign owners, and foreign entities registered to do business in the U.S. do not need to report any information about U.S. persons. Foreign entities that were registered to do business in the U.S. before March 21, 2025, must file their BOI reports no later than April 20, 2025, and any foreign entities that register to do business in the U.S. after March 21, 2025, must file the report within 30 days after receiving notice that their registration is effective.

The CTA Moving Forward

Although this rule relaxes requirements for U.S. entities, the CTA may not support FinCEN’s interim final rule. With the Supreme Court’s ruling in Loper Bright V. Raimondo, ending deference to regulatory agencies, the interim final rule may come under scrutiny in the courts. If the interim final rule is invalidated, domestic entities could be in the same position as before, having to report BOI to FinCEN.

As a result, while there is no need for domestic entities to report BOI to FinCEN at the moment, domestic entities exempted by the interim final rule should be aware that a court challenge to the interim rule could reinstate reporting requirements, and thus should plan accordingly.

The End of the Corporate Transparency Act Regime for Domestic Companies

On March 21, 2025, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) issued an interim final rule that exempts all domestic companies and persons from all Corporate Transparency Act (CTA) requirements. The only entities remaining in scope are ones that were formed under the laws of a foreign jurisdiction and subsequently registered to do business in a U.S. jurisdiction. Even for these foreign entities, any beneficial owners that are U.S. persons are exempt from all beneficial ownership reporting.

FinCEN’s interim final rule wraps a tumultuous year for the CTA. After a series of federal district court injunctions and stays, FinCEN had initially announced CTA reporting requirements would move forward in full. Then, on March 2, 2025, the Treasury Department, of which FinCEN is a part, announced it would not enforce any CTA requirements against U.S. reporting companies or citizens. The March 2 announcement left many U.S. companies in limbo, because the Treasury Department’s announcement concerned only enforcement, and did not actually lift legal requirements. The distinction between non-enforcement and non-compliance can be important, especially when a company makes representations that they are in compliance with legal requirements. The March 21 interim final rule alleviates these concerns as it lifts the legal compliance requirements for all domestic companies.

Foreign reporting companies have until April 20, 2025 to file beneficial ownership information with FinCEN. Foreign entities that register in a U.S. jurisdiction for the first time after March 31 have 30 days from the date of registration to file an initial beneficial ownership information report.

What is next for beneficial ownership reporting? As far as the CTA goes, FinCEN is accepting comments on the interim final rule and plans to issue a final rule later this year. It is possible we see further changes to the reporting framework, either through the comment process or through additional challenges in the courts. Beyond the CTA, several states are at various stages of implementing their own beneficial ownership reporting regimes. For example, the New York legislature has passed the New York LLC Transparency Act, which largely mirrors the original CTA reporting regime, although it applies only to LLCs. It is schedule to take effect on January 1, 2026. Other states are actively considering beneficial ownership reporting requirements, including Massachusetts, Maryland and California, and it is possible we see further state level regimes ramp up now that the federal rules have been heavily curtailed.

Appeals Court Reinstates MSPB Chair Cathy Harris After Trump Firing, Restoring Quorum on Board

On April 7, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia issued a ruling temporarily reinstating Cathy A. Harris, who leads the Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB), after the Trump administration fired her without cause in February. The court voted 7-4 to vacate an earlier ruling from a three-judge panel on the court which had upheld the firing.

“The DC Circuit has followed the law and has prevented the President of the United States from undermining the entire civil service,” said whistleblower attorney Stephen M. Kohn, founding partner of Kohn, Kohn & Colapinto and Chairman of the Board of National Whistleblower Center. “If the president’s decision to terminate Cathy Harris was upheld the MSPB would have lost its quorum and would have been unable to issue relief to the millions of civil servants protected under civil law.”

“Every federal employee would have been at risk of being illegally fired with no effective recourse if President Trump delayed or failed to nominate a successor and the U.S. Senate delayed or failed to approve the nomination,” Kohn continued. “The MSPB has exclusive jurisdiction over the majority of civil servants. Whistleblowers would be most at risk. Whistleblowers and anyone who dared to blow the whistle would be at risk for summary and illegal discharge.”

President Trump fired Cathy Harris on February 10 without cause. Under federal law, members of the MSPB may be removed from office “only for inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance in office.” According to the DC Circuit, while the Supreme Court has found certain laws with removal protections unconstitutional, it “has repeatedly stated that it was not overturning the precedent established in Humphrey’s Executor and Wiener for multimember adjudicatory bodies.”

If Harris is removed from her post, the MPSB would be without the two members needed for a quorum. The MSPB, a quasi-judicial agency, is the sole venue to adjudicate whistleblower complaints and anti-retaliation claims brought by federal employees. For a period of five years from 2017 through 2022, the MSPB lacked a quorum, meaning they were unable to issue final rulings in whistleblower retaliation cases. By the time quorum was established, the Board faced a backlog of over 3,500 cases.

On March 26, Senator Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) introduced the Congressional Whistleblower Protection Act of 2025. The bill strengthens protections for federal employee whistleblowers who make disclosures to Congress, expanding the types of whistleblowers covered and granting them the right to have their case heard in federal court if there are delays in administrative proceedings. Under the bill, a federal employee whistleblower may seek relief in federal court if corrective action is not reached within 180 days of filing a complaint to the MSPB.

Buyer Beware: Trying to Avoid or Reduce Tariffs

As the typical tariffs on many goods from China have soared to at least 45 percent, some suppliers in China are offering U.S. purchasers a way of avoiding or reducing the tariffs. However, U.S. importers should carefully scrutinize such offers. Attempting to lower or avoid tariffs without the proper analysis and exercise of reasonable care could lead to enforcement actions by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and significant monetary penalties.

The reported proposal: Some suppliers in China are suggesting to their U.S. customers that the supplier issue an invoice for the imported goods not including engineering, patent licensing, setup, or other overhead costs of manufacturing the goods in China. The suppliers would then invoice the U.S. purchasers separately for those costs. That second invoice would not be sent with the shipped goods.

In other words, the declared, dutiable value of the goods would be lower than the total price actually paid by the U.S. importer to the foreign seller. The amount of duties, which are applied as a percentage of the dutiable value, would thus be lowered.

The problem with such a proposal:

1. Under the U.S. Customs valuation rules, the dutiable value (usually the “transaction value”) is generally the price paid or payable to the foreign seller. If certain pre-import costs such as design or engineering are not included in the price of the goods, those costs must be added to the price of the goods to calculate the dutiable value. All payments made to the foreign seller are presumed to be part of the dutiable value, and the U.S. importer of record bears the burden of overcoming this presumption. Thus, failure to include such costs in the dutiable value generally would be a violation of CBP regulations.

2. The U.S. importer of record bears all the liability for underpayments of duties to CBP and for fines and penalties applied as a result of the violation. Civil fines of an amount up to the domestic value of the imported merchandise can be imposed, and criminal penalties can also be imposed for knowing and willful violations. The foreign seller will have been paid by the U.S. purchaser and will not be responsible for what could be significant amounts owed to CBP.

3. Significant enforcement of tariff evasion on goods imported from China is anticipated, including initiation of False Claims Act cases by the Department of Justice. Furthermore, a presidential proclamation issued in February on additional steel and aluminum tariffs directs CBP to impose maximum penalties for misclassification of such products to evade tariffs.

Given all of these circumstances, U.S. importers should exercise caution when considering any tariff avoidance or reduction proposals offered by suppliers in China.

Modern Piracy: Insurance Coverage Options for Cargo Theft and Related Losses

Theft in the cargo industry has skyrocketed in recent years. In the first half of 2024, cargo thefts rose 49 percent and the average loss per shipment by 83 percent. Given these dramatic spikes in cargo theft, policyholders whose operations rely on the safe transportation and trade of cargo should take steps to mitigate against the potential losses of a cargo-theft event. We discuss below the insurance coverage options available to policyholders that can help protect against the risks and losses associated with cargo-related theft if such a loss occurs.

The Spike in Cargo Theft

Certain types of cargo thefts have skyrocketed; between 2022 and 2024, strategic theft (theft by trickery or deception) increased 1455 percent. Similarly, between the last quarters of 2021 and 2022, double brokering rose 400 percent. Other types of theft include forging or altering documents, impersonating legitimate shippers, and simple theft (physically stealing items or shipments).

The causes of this peak vary. The nearly tenfold increase in the cost to move containers between the U.S. and China and worldwide inflation has made shipping that much more expensive. Cost-cutting measures in response to higher costs have eroded the relationships between industry players—notably, many shipments are moved by posting on a load board rather than through a trusted shipping company or professional intermediary—and normalized transacting with strangers. At the same time, thieves have become more familiar with technology and obtained access to powerful tools such as AI to fool industry players.

The Impacted Players

The owners of the stolen cargo are not the only players impacted when cargo is stolen. Any number of parties in the supply chain may suffer losses if a shipment is stolen. Manufacturers and retailers lose property. Shippers lose goodwill and reputation among their clients and may be liable to those clients for the property loss. Recently, brokers have lost, too, as other parties in the chain allege that broker negligence in managing shipments allowed thieves to submit bids, double broker, or reroute shipments.

Insurance Offerings to Protect Against Cargo-Related Theft and Related Losses

Wherever your organization is located in the supply chain, insurance can help offset losses from theft. While traditional forms of insurance may be helpful, insurers have responded to the increased needs of the transportation industry by creating a number of specialized products targeting specific risks.

Cargo Insurance. Cargo insurance—a form of property insurance sometimes called “all risk” because it covers all perils except those specifically excluded—is typically obtained by shippers and protects goods in transit. It is often broken up into ocean marine (transit over the ocean) and inland marine (transit over land). Some insurers offer insurance products further tailored to the type of party, risk, or goods being shipped, allowing shippers who handle high-value loads to obtain additional peace of mind. Brokers may consider contingent cargo loss insurance, which helps protect brokers when the shipper’s cargo insurance policy does not cover a loss and the manufacturer turns to the broker to pay.

When obtaining a cargo insurance policy, it is important to review the conditions of coverage and exclusions. Cargo policies may require the policyholder to implement certain security measures to protect the shipment or pack the shipment in a certain way (which could result in delayed payment or litigation while the facts are investigated). They may also exclude some shipments, notably high-value goods or goods that thieves often target.

Liability Insurance. A staple of any good risk management program, liability insurance covers defense (attorneys’ fees) and indemnity (damages) costs in a lawsuit to recover the costs of a shipment. Shippers should consider general liability insurance, which covers losses from damage to a third party’s property as well as defense costs in the lawsuit. Brokers may obtain a comprehensive policy that bundles general liability insurance with other types of coverages, such as contingent cargo and errors and omissions (“E&O,” which covers defense and indemnity costs from the broker’s alleged negligence in brokering the shipment—for example, if double brokering occurs).

Cyber Insurance. All parties in the supply chain should consider obtaining cyber insurance. As noted above, thieves are increasingly technologically savvy, using AI and other digital tools to impersonate shippers and brokers. Cyber insurance may cover costs incurred when thieves access credentials or digital information and then use that information to scam third parties. It may also cover costs to expel intruders from company computer systems or pay to recover data ransomed by thieves. Cyber policies are often custom and negotiated on a policyholder-by-policyholder basis, so companies should carefully review their offers of coverage and potential exclusions before buying a policy.

Conclusion

Events like cargo-theft—which are on the rise—can cause significant lost profits, extra expenses, and supply-chain disruptions. Commercial policyholders whose operations involve cargo should ensure they can protect against these events and resultant losses. Policyholders should carefully review their existing insurance policies to determine which coverages exist, and whether additional or modified terms are warranted in the event of a cargo-related loss.

DOJ Plans Sweeping Reorganization of ENRD

The US Department of Justice (DOJ) is planning a major reorganization of the Environment and Natural Resources Division (ENRD) that includes consolidating several sections within the division into other DOJ divisions, as well as eliminating field offices.

The DOJ’s reorganization plan is outlined in a March 25 memorandum from Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche entitled “Soliciting Feedback For Agency Reorganization Plan and RIF.” The memo summarizes the DOJ’s March 13 report to the Office of Personnel Management and Office of Management and Budget about potential reorganizations and reductions in workforce (RIF) and solicited feedback from heads of department components by April 2. While the memo discusses proposals for reorganizing several offices, this post focuses on its impact on ENRD.

We previously reported about significant senior leadership changes among career civil service managers within various sections housed within ENRD, specifically the chiefs of the natural resources, environmental enforcement, environmental crimes, and appellate sections (see here). Those managers were offered new duties related to sanctuary city immigration work, though some chose to resign rather than accept the new duties. This new proposal moves towards more significant changes.

According to the memo, the plan would include consolidating civil appeals work currently performed within the ENRD’s civil appeals section into the DOJ Civil Division, and criminal appellate work currently within ENRD would be transferred to the US Attorneys’ Offices. The duties currently performed within the ENRD Law and Policy Section would be transferred into the DOJ Office of Legal Policy. The memo does not address changes specific to the enforcement, defense, or natural resources sections within ENRD. Nevertheless, these proposed changes represent the first significant restructuring of ENRD in decades, as various duties currently performed within ENRD are stripped away and performed elsewhere.

Regarding the field offices, those housing ENRD attorneys that would be closed under the proposal include Denver, Colorado, Sacramento, California, Seattle, Washington, and San Francisco, California. It is unclear if ENRD attorneys currently assigned to those offices would have the option of reassignment to another duty station.

It is also unclear from the memo if and when these various proposals would ultimately result in RIF. Nor is it apparent which of these proposals under consideration will ultimately occur.

Federal Crypto Ownership: Compliance Implications of the Strategic Bitcoin Reserve and U.S. Digital Asset Stockpile

Following President Trump’s March 6 Executive Order establishing a Strategic Bitcoin Reserve and U.S. Digital Asset Stockpile, federal agencies and market participants may begin to grapple with the operational and compliance implications of the federal government’s proposed foray into crypto ownership and stewardship. While many of the program’s details remain under development, the initiative raises questions related to governance, custody, disclosure, and alignment with existing financial and national security laws.

As the U.S. begins to treat digital assets not just as speculative instruments, but as components of sovereign infrastructure, various compliance obligations—some existing, others emerging—will come into play.

Asset Classification and Oversight

Federal agencies charged with oversight of crypto markets—including the SEC, CFTC, FinCEN, and the IRS—will likely need to coordinate with the Presidential Working Group on Digital Asset Markets (previously discussed here), which the executive order references as a key platform for developing operational standards for the reserve. This could include initiatives such as (i) developing inter-agency compliance protocols for classification and treatment of different digital assets, and (ii) addressing whether sovereign ownership triggers obligations under existing securities, commodities, or money transmission laws when assets are transferred, staked, or deployed in decentralized finance protocols to generate yield.

Custody, Security, and Risk Controls

Federal crypto assets are currently held under a patchwork of custody arrangements, often involving third-party custodians retained by the DOJ and U.S. Marshals Service (previously discussed here). The strategic reserve initiative may prompt more formalization and regulation of public-sector crypto custody, including:

Implementation of multi-signature wallets and layered access controls;

Segregated storage of assets across agencies, or centralized consolidation under a single federal custodian;

Audit process for confirming provenance and security of network hardware components used to hold and transfer the digital asset reserve; and

Mandated internal controls and periodic auditing of wallet activity, private key management, and access logs.

Anti-Money Laundering, Sanctions, and Forfeiture Frameworks

As the federal government expands its digital asset holdings, it must maintain robust anti-money laundering (AML) and sanctions compliance for both seized and strategically acquired assets. This could include:

Screening assets and counterparties for exposure to OFAC-sanctioned jurisdictions or wallet addresses;

Establishing procedures for chain-of-custody documentation in asset acquisition or liquidation; and

Determining whether assets acquired through strategic procurement (rather than through seizure in connection with illicit activities) require new reporting or risk management practices under the Bank Secrecy Act and Patriot Act.

Furthermore, to the extent the Digital Asset Stockpile includes tokens used in DeFi protocols or cross-border settlement, further questions arise regarding whether the government must comply with evolving international AML and counter-terrorist financing standards.

Putting It Into Practice

The creation of a Strategic Bitcoin Reserve and Digital Asset Stockpile marks a dramatic turnaround in how the federal government engages with crypto assets—not only as a regulator, but now as a market participant, custodian, and price maker. As this strategy unfolds, agencies and contractors involved in its implementation will need to build robust compliance infrastructures informed by existing financial laws, agency protocols, and national security objectives.

Listen to this post

How to Report a Crypto Ponzi Scheme and Earn an SEC Whistleblower Award

Crypto Ponzi Schemes on the Rise

The rise in popularity of cryptocurrency has created fertile ground for fraud, including Ponzi schemes. Crypto Ponzi schemes function similarly to traditional Ponzi schemes by misleading investors into believing their returns are generated from legitimate trading or business activities. In reality, the fraudulent cryptocurrency companies use new investor funds to pay earlier investors, eventually leading to collapse when recruitment slows.

The SEC remains committed to rooting out these crypto frauds. On February 21, 2025, SEC Commissioner Hester M. Peirce stated:

[T]he Commission’s efforts continue unabated to combat fraud involving securities, including crypto assets that are securities or that were offered and sold as part of an investment contract, and tokenized securities. The Commission welcomes the public’s tips about securities violations.

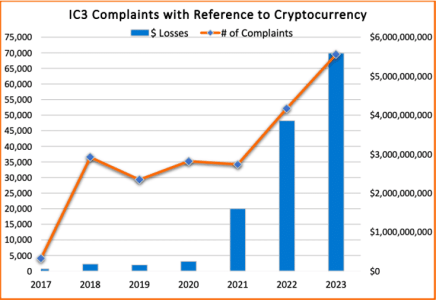

And, indeed, whistleblower tips are needed to combat the rising number of crypto schemes. According to the FBI’s 2023 Cryptocurrency Fraud Report, crypto frauds account for a majority of losses due to financial fraud:

In 2023, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) received more than 69,000 complaints from the public regarding financial fraud involving the use of cryptocurrency, such as bitcoin, ether, or tether. Estimated losses with a nexus to cryptocurrency totaled more than $5.6 billion. While the number of cryptocurrency-related complaints represents only about 10 percent of the total number of financial fraud complaints, the losses associated with these complaints account for almost 50 percent of the total losses.

The FBI’s report also highlights the significant increase in losses due to crypto frauds since 2021:

Under the SEC Whistleblower Program, whistleblowers can submit tips anonymously to the SEC through an attorney and be eligible for an award for exposing any material violation of the federal securities laws, including crypto Ponzi schemes and scams. Since 2011, whistleblower tips have enabled the SEC to bring enforcement actions resulting in more than $6 billion in monetary sanctions and the SEC has issued more than $2.2 billion in awards to whistleblowers. The largest SEC whistleblower awards to date are $279 million (May 5, 2023), $114 million (Oct. 22, 2020), and $110 million (Sept. 15, 2021).

This article discusses: 1) how to identify a crypto Ponzi scheme; 2) the SEC Whistleblower Program; 3) how to report a crypto Ponzi scheme and earn an SEC whistleblower award; and 4) examples of recent SEC enforcement actions against crypto Ponzi schemes and scams.

How to Identify a Crypto Ponzi Scheme

The SEC and FBI have warned investors about common red flags associated with Ponzi schemes, including crypto Ponzi schemes, such as:

High returns with little or no risk: Claims of consistent, substantial profits is a hallmark of Ponzi schemes. Every investment carries some degree of risk and investors should be suspicious of any “guaranteed” investment opportunity.

Complex or secretive investment strategies: Fraudsters often claim proprietary or undisclosed trading algorithms that cannot be independently verified.

Difficulty withdrawing funds: Investors may experience delays or be encouraged to “roll over” their investment for even higher returns. Additionally, some crypto frauds require investors to pay “fees” prior to withdrawing their (fake) profits.

Heavy recruitment incentives: Some schemes require investors to recruit new members to receive payouts, resembling pyramid structures.

Anonymous or unlicensed promoters: Many crypto frauds are run by unknown entities or individuals with no verifiable credentials.

Domain or website names that impersonate legitimate crypto companies and exchanges: Many crypto Ponzi schemes would be halted in their tracks if investors conducted research on their domain names, which would reveal that the websites are fake and/or were created recently to resemble a successful cryptocurrency company or exchange. Investors can use resources, such as Wayback Machine or Whois lookup, to research domains and determine, at a minimum, when a website was created.

If an investment opportunity sounds too good to be true, it likely is.

SEC Whistleblower Program

Under the SEC Whistleblower Program, the SEC will issue awards to whistleblowers who provide original information, including information about Ponzi schemes, that leads to successful enforcement actions with total monetary sanctions in excess of $1 million. A whistleblower may receive an award of between 10% and 30% of the total monetary sanctions collected. If represented by counsel, a whistleblower may submit a tip anonymously to the SEC.

In its short history, the SEC Whistleblower Program has had a tremendous impact on securities enforcement and has been replicated by other domestic and foreign regulators. Since 2011, the SEC has received an increasing number of whistleblower tips in nearly every fiscal year. In FY 2024, the SEC received approximately 24,980 whistleblower tips and awarded over $225 million to whistleblowers.

How to Report a Crypto Ponzi Scheme

To report a Ponzi scheme and qualify for an award under the SEC Whistleblower Program, the SEC requires that whistleblowers or their attorneys report the tip online through the SEC’s Tip, Complaint or Referral Portal or mail/fax a Form TCR to the SEC Office of the Whistleblower. Prior to submitting a tip, whistleblowers should consult with an experienced whistleblower attorney and review the SEC whistleblower rules to, among other things, understand eligibility rules and consider the factors that can significantly increase or decrease the size of a future whistleblower award.

SEC Targets Crypto Ponzi Schemes

The SEC has aggressively pursued crypto-related fraud, including crypto Ponzi schemes and other fraudulent investment scams. Below are some examples of recent crypto-related frauds that were halted by the SEC. Notable cases include:

In August 2024, the SEC filed a lawsuit against NovaTech and its promoters, alleging they operated a fraudulent crypto pyramid scheme that raised around $650 million from over 200,000 investors worldwide. According to the SEC’s complaint, the defendants operated NovaTech as a multi-level marketing (MLM) and crypto asset investment program from 2019 through 2023. They lured investors by claiming NovaTech would invest their funds on crypto asset and foreign exchange markets. In reality, NovaTech used the majority of investor funds to make payments to existing investors and to pay commissions to promoters, using only a fraction of investor funds for trading. The complaint further alleges that the Petions siphoned millions of dollars of investor assets for themselves.

In August 2024, the SEC obtained emergency asset freezes against brothers Jonathan and Tanner Adam for allegedly conducting a $60 million Ponzi scheme affecting more than 80 investors across the U.S. According to the SEC’s complaint, the brothers promised up to 13.5% monthly returns, claiming the funds would be used in a crypto asset trading platform. Instead, they used new investor funds to pay earlier investors and for personal expenses, including luxury items and real estate.

In November 2022, the SEC charged Douver Torres Braga, Joff Paradise, Keleionalani Akana Taylor, and Jonathan Tetreault for their roles in Trade Coin Club, a fraudulent crypto Ponzi scheme that raised more than 82,000 bitcoin, valued at $295 million at the time, from more than 100,000 investors worldwide. According to the SEC’s complaint, Braga created and controlled Trade Coin Club, a MLM program that operated from 2016 through 2018 and promised profits from the trading activities of a purported crypto asset trading bot. The SEC also alleged that Trade Coin Club operated as a Ponzi scheme and that investor withdrawals came entirely from deposits made by investors, not from any crypto asset trading activity by a bot or otherwise.

In August 2022, the SEC charged 11 individuals for their roles in creating and promoting Forsage, a fraudulent crypto pyramid and Ponzi scheme that raised more than $300 million from retail investors worldwide. According to the SEC’s complaint, Forsage allowed millions of retail investors to enter into transactions via smart contracts that operated on the Ethereum, Tron, and Binance blockchains. Forsage allegedly operated as a pyramid scheme for more than two years, in which investors earned profits by recruiting others into the scheme. Forsage also allegedly used assets from new investors to pay earlier investors in a typical Ponzi structure.

As crypto-related fraud continues to evolve, the SEC relies on whistleblowers to expose these scams and protect investors. See the SEC’s Investor Alert: Watch Out for Fraudulent Digital Asset and “Crypto” Trading Websites.

FinCEN Warns US Financial Institutions of Bulk Cash Smuggling Risks from Mexico-Based Cartels

Go-To Guide:

FinCEN recently issued an alert to warn U.S. financial institutions, particularly depository institutions and money services businesses (MBSs), of the risks and red flags associated with bulk cash smuggling by Mexico-based drug cartels and other transnational criminal organizations.

FinCEN’s alert highlights the role played by Mexican and U.S. armored car services in knowingly or unknowingly introducing cartel proceeds into the U.S. financial system.

The alert, together with several other policy announcements from the Trump administration, signals an increased regulatory and enforcement focus on the laundering of cartel funds through U.S. financial institutions.

Financial institutions and common carriers of currency should review and update, as necessary, their compliance programs to address the identified money laundering risks.

On Mar. 31, 2025, as part of its responsibilities in administering the U.S. Bank Secrecy Act (BSA), the Department of the Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) issued an alert urging financial institutions to be vigilant in identifying and reporting transactions potentially related to the cross-border smuggling of bulk cash from the United States into Mexico, and the repatriation of bulk cash into the U.S. and Mexican financial systems by Mexico-based drug cartels and other transnational criminal organizations (TCOs).

The alert highlights one particular money laundering typology that drug cartels have been observed using—namely, utilizing Mexico-based businesses as cover to repatriate smuggled bulk cash back into the United States via foreign and domestic armored car services and air transport. According to FinCEN, this bulk cash is then often delivered by an armored car service to a U.S. financial institution, typically a depository institution or MSB, and either deposited into accounts that are owned by the Mexico-based businesses or transmitted by the MSBs on the Mexico-based businesses’ behalf.

Highlights for US Depository Institutions and MSBs

The alert identifies several red flags for this money laundering typology that U.S.-based depository institutions and MSBs should monitor for, as appropriate, including:

a customer who owns a Mexico-based business receiving a large credit, either from a U.S.-based armored services (ASC) company or after the customer has deposited bulk cash into the bank’s vault at a U.S.-based ACS secure storage facility;

receipt of a large cross-border wire transfer from a Canada-based financial institution to the bank account of a customer that owns a Mexico-based business;

the transportation of large volumes of cash by an ACS company or passenger vehicles to a U.S.-based MSB located along the southwest border, followed by rapid transfer to Mexico; and

delivery of a large volume of cash to a U.S.-based financial institution via an ACS company on behalf of a customer that operates or is affiliated with a Mexico-based business, or a business located near the U.S. southwest border, followed by (i) rapid movement of funds to a financial institution based in Mexico, (ii) a transfer to another affiliated business in the United States, or (iii) transfer to purchase a large volume of goods.

Highlights for Armored Car Services

The alert also highlights red flags that ACS companies should monitor for, including, but not limited to, where a Mexico-based business or individual requests that bulk cash be transported into the United States and/or accepted by a U.S. financial institution, but (i) the funds are not commensurate with the size of the business or the business profile; (ii) the requestor is reluctant to provide information, or provides inconsistent information, on the currency originator; or (iii) the request does not provide a clear explanation of the funds’ source.

The alert also notes FinCEN’s view that certain armored car services and other common carriers of currency may be engaged in “money transmission” under the BSA, which would require FinCEN registration and the implementation of a BSA-compliant anti-money laundering (AML) compliance program. Earlier this year, FinCEN and the U.S. Department of Justice concluded parallel civil and criminal resolutions, respectively, against a major U.S.-based ACS for failure to register with FinCEN and failure to maintain an adequate BSA/AML compliance program.1

Recent Related Announcements and Actions

This alert follows several additional federal actions that, like the resolutions above, signal heightened regulatory and enforcement focus on the AML and counter-terrorism risks drug cartels pose, including the role U.S. financial institutions and ACS companies—knowingly or unknowingly—play. These include:

a Jan. 20, 2025, Executive Order in which President Donald Trump identified drug cartels as a national security threat, broadening the authority of the State Department to designate such cartels as Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs);

the State Department’s designation, on Feb. 20, 2025, of several infamous Central American drug cartels, including Sinaloa, as FTOs under that Executive Order, creating additional legal risks for companies found to have provided financial services to cartels, including under the so-called “Material Support Statute” set forth in 18 U.S.C. § 2339B; and

the U.S. Attorney General’s identification of criminal activity connected to drug cartels, including the laundering of funds for cartels, as a DOJ enforcement priority.

Key Takeaways

Banks, MSBs, ACS companies, and other common carriers of currency should review their AML compliance programs (whether federally-mandated or voluntary) to ensure that the risks identified in the alert are appropriately analyzed and addressed, where necessary.

ACS companies and other common carriers of currency should review their operations with counsel to understand, and potentially respond to, the risk that FinCEN may deem certain activity to be BSA-regulated money transmission.

All companies, whether subject to the BSA or not, that are involved in cross-border cash shipments in any capacity should review their policies for filing Currency or Monetary Instruments Reports (CMIRs). CMIRs must be filed anytime a person attempts or actually does physically transport, mail, or ship, or cause to be physically transported, mailed, or shipped, currency or other monetary instruments in an aggregate amount exceeding $10,000 at one time into or out of the United States.

1 Although the BSA’s definition of “money transmission” includes an exception for certain currency transporters, a 2014 FinCEN administrative ruling stated that the exception does not apply when the consignee (i.e., the person appointed by the shipper to receive the currency or monetary instruments) is a third party.

10 Important Insights for Procurement Fraud Whistleblowers in 2025

If you have information about procurement fraud, providing this information to the federal government could lead to the recovery of taxpayer funds and put a stop to any ongoing fraud. It could also entitle you to a financial reward. In addition to providing strong protections to procurement fraud whistleblowers, the False Claims Act entitles whistleblowers to financial compensation when the information they provide leads to a successful enforcement action.

Whether you are interested in seeking a financial reward or you are solely focused on ensuring integrity and accountability within the federal procurement process, if you have information about procurement fraud, it will be important to make informed decisions about your next steps. While protections and financial incentives are available, whistleblowers who wish to expose procurement fraud must meet various substantive and procedural requirements, and they must come forward before someone else beats them to it.

“Federal procurement fraud is a pervasive issue, and whistleblowers play a critical role in the government’s fight against fraudulent bidding, contracting, and billing practices. For those who are thinking about serving as procurement fraud whistleblowers, understanding the federal whistleblowing process is critical for making informed decisions about their next steps.” – Dr. Nick Oberheiden, Founding Attorney of Oberheiden P.C.

So, what do you need to know if you are thinking about reporting procurement fraud to the federal government? Here are 10 important insights for whistleblowers in 2025:

1. Suspecting Procurement Fraud and Being Able to Prove Procurement Fraud Are Not the Same

Filing a whistleblower complaint for procurement fraud requires more than just suspicion of wrongdoing. To qualify as a federal whistleblower—and to become eligible for the protections and financial compensation that are available—you must be able to help the federal government prove that a contractor or subcontractor has violated the law, whether through false statements, bid rigging, overbilling, or other fraudulent actions.

As a result, if you just have general concerns about procurement fraud, these concerns—on their own—will generally be insufficient to substantiate a procurement fraud whistleblower complaint. However, if you have inside information about a specific form of procurement fraud, then this is a scenario in which filing a whistleblower complaint may be warranted.

2. You Don’t Need Conclusive Proof to Serve as a Procurement Fraud Whistleblower

To be clear, however, filing a whistleblower complaint does not require conclusive proof of government procurement fraud. Instead, to file a whistleblower complaint under the False Claims Act in federal court, you must be able to make allegations that “have evidentiary support or, if specifically so identified, will likely have evidentiary support after a reasonable opportunity for further investigation.” As a result, you do not need any specific type or volume of evidence to serve as a procurement fraud whistleblower. If you have reason to believe that government contract fraud has been committed (or is in the process of being committed), this is generally all that is required.

With that said, the more evidence you have, the better—and you will want to work closely with an experienced procurement fraud whistleblower lawyer to determine whether you can meet the federal pleading requirements. If you need additional information, your lawyer can advise you regarding the information needed and how to collect it, as discussed in greater detail below.

3. You Must Be the First to Come Forward with Material Non-Public Information

Another requirement for serving as a procurement fraud whistleblower is that you must be privy to non-public information. In most cases, you also need to be the first to share this information with the federal government, though certain exceptions may apply.

With this in mind, while it is important to make an informed decision about whether to file a procurement fraud whistleblower complaint under the False Claims Act, it is also important to act promptly. A lawyer who has experience representing federal whistleblowers should understand that time is of the essence and should be able to assist you with making an informed decision as efficiently as possible.

4. While You Should Protect Any Evidence You Have, You Should Be Cautious About Collecting Additional Evidence

If you have collected or copied any evidence from your employer’s facilities or computer systems, you should protect this evidence to the best of your ability. Keep any hardcopy documents in a secure location and keep any electronic files on a secure storage device (and not in the cloud). This is important for your protection and for helping to ensure that you remain eligible to secure federal whistleblower status.

At the same time, if you are aware of additional evidence that you have not yet collected, you will need to be cautious about collecting this additional evidence. Even when you are taking steps to expose fraud, it is important to avoid violating employment policies or non-disclosure obligations–as doing so could put you at risk. While there are rules on when employers can (and can’t) enforce these types of restrictions to prevent whistleblowing, here too, you need to ensure that you are making informed decisions. An experienced procurement fraud whistleblower lawyer will be able to help.

5. If You Come Forward with Qualifying Information, the Government Will Have a Duty to Investigate Further

A key aspect of the procurement fraud whistleblower process is that the government has a duty to investigate allegations that warrant further inquiry. This is due, in part, to the nature of the qui tam procedures under the False Claims Act. The government isn’t necessarily required to pursue an enforcement action—this decision will be based on the outcome of its investigation—but it is generally required to determine if enforcement action is warranted.

With that said, not all substantiated allegations of government procurement fraud will necessarily warrant a federal investigation. If the amount at issue is small, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) may be justified in deciding not to devote federal resources to a full-blown federal inquiry. A whistleblower lawyer who has significant experience in qui tam cases will be able to assess whether the DOJ is likely to determine that your allegations warrant an investigation.

6. Federal Authorities Will Expect to Be Able to Work With You During Their Procurement Fraud Investigation

If you file a procurement fraud whistleblower complaint and the government decides to open an investigation, you will be expected to work with the government during the investigative process. Whether, and to what extent, you remain involved is up to you–but it is important to understand that federal agents and prosecutors will be expecting you to assist to the extent that you can. Your lawyer can advise you here as well, and can communicate with federal authorities on your behalf if you so desire.

7. Procurement Fraud Whistleblowers Are Entitled to Protection Against Retaliation and May Be Entitled to Financial Rewards

If you qualify as a procurement fraud whistleblower under the False Claims Act, you will be entitled to protection against retaliation in your employment (if you are currently employed by the contractor or subcontractor that you are accusing of fraud). Your employer will be prohibited from taking adverse employment action against you based on your decision to blow the whistle; and, if it retaliates against you illegally, you will be entitled to clear remedies under federal law.

If the information you provide leads to a successful enforcement action, you may also be entitled to a financial reward. Subject to certain stipulations, under the False Claims Act, whistleblowers who help the government recover losses from procurement fraud are entitled to between 10% and 30% of the amount recovered.

8. Hiring an Experienced Whistleblower Lawyer is Important, and You Can Do So at No Out-of-Pocket Cost

While filing a procurement fraud whistleblower complaint is a complex process, you do not have to go through the process on your own. You can—and should—hire an experienced whistleblower lawyer to represent you at no out-of-pocket cost. An experienced lawyer will be able to advise you of your options every step of the way, answer all of your questions, and interface with the federal government on your behalf.

9. There Are Several Reasons to Consider Blowing the Whistle on Procurement Fraud

If you have information about government procurement fraud, there are several reasons to consider coming forward. While the prospect of a financial reward is appealing to many, blowing the whistle is also simply the right thing to do. Contractors that engage in procurement fraud deserve to be held accountable, and helping federal and state governments recover taxpayer funds—while also helping to mitigate the risk of future losses—is beneficial for everyone.

10. It Is Up to You to Decide Whether to Blow the Whistle on Procurement Fraud

Ultimately, however, whether you decide to serve as a procurement fraud whistleblower is up to you. While an experienced whistleblower lawyer will help you make sound decisions, your lawyer should not pressure you into coming forward. It is a big decision to make, and it is one that you need to make based on what you believe is the right thing to do under the circumstances at hand.

As we mentioned above, however, time can be of the essence in this scenario. With this in mind, if you believe that you may have inside information, you should not wait to report fraud to the government. Your first step is to schedule a free and confidential consultation with an experienced procurement fraud whistleblower lawyer—and this is a step that you should take as soon as possible.

Understanding the U.S. Embassy Paris Certification Requirement

Last week, the U.S. Embassy in Paris issued a letter and certification form to multiple French companies requiring companies that serve the U.S. Government to certify their compliance with U.S. federal anti-discrimination laws. This certification request was issued in furtherance of President Trump’s Executive Order 14173 on Ending illegal Discrimination and Restoring Merit-Based Opportunities, issued on January 21, 2025. This Order addresses programs promoting Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) and requires that government contractors’ employment, procurement and contracting practices not consider race, color, sex, sexual preference, religion or national origin in ways that violate the United States’ civil rights laws.

Certification Contents

The certification requires U.S. Government contractors to certify that they comply with all applicable U.S. federal anti-discrimination laws and do promote DEI in violation of applicable U.S. federal anti-discrimination laws.

While the letter was issued by the U.S. Embassy in Paris and is arguably limited to contractors serving that embassy, the requirement under the Executive Order extends to all contractors doing business with any U.S. Government agency.

Any company submitting the certification with knowledge that it is false will be deemed to have violated the U.S. False Claims Act, which imposes liability on individuals and companies who defraud governmental programs.

Implications for French Companies

This letter raises questions about the extraterritorial application of U.S. laws to foreign companies and their reach. In particular, while the Executive Order clearly applies to companies (irrespective of nationality) that directly supply or provide services to the U.S. Government, it is unclear whether, for example, the French parent of a U.S. subsidiary providing services to the U.S. Government would be subject to the certification.

The issue is complicated by the fact that French law in some ways conflicts with the provisions of the Executive Order – for instance, requiring that mid-sized and large companies have a minimum percentage of women sitting on their boards.

Neither the Executive Order nor the documents mention any exemptions or carve-outs for suppliers and service providers.

Conclusion

The U.S. Embassy’s certification requirement underscores the current complexities faced by international businesses in dealing with the U.S. Government. French companies should consider carefully assessing their DEI programs and overall compliance with U.S. federal laws while continuing to adhere to their own legal obligations, striking a careful balance as best they can.