Eleventh Circuit Addresses Rule 9(b) Heightened Pleading Standard in False Claims Act Case

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit has concluded that a successful False Claims Act (FCA) claim should “allege not just a scheme, but a scheme that actually led to false claims being submitted to the government”—and must do so with particularity.

This heightened pleading standard cost the qui tam relators in United States ex rel. Vargas v. Lincare, Inc. et al., 24-11080, 2025 WL 1122196 (11th Cir. Apr. 16, 2025), three out of the four claims in their fourth amended complaint. The U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Florida had dismissed the entire complaint for failing to plead sufficient facts under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 9(b) (“Rule 9(b)”).

The Eleventh Circuit reversed in part, holding that certain allegations of upcoding were adequately pleaded under Rule 9(b) to survive a motion to dismiss. The complaint alleged that the defendants, a medical supplier and its subsidiary, improperly coded the accessories (i.e., batteries, chargers, and cables) of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machines as ventilator accessories. Ventilator accessories are covered by TRICARE, a health insurance program for military personnel and their families; CPAP accessories are not.

The Eleventh Circuit affirmed the dismissal of claims alleging: (1) the routine waiver of patient copays in violation of TRICARE conditions of participation; (2) automatic shipments of CPAP supplies, such as masks (TRICARE covers these supplies only upon a request); and (3) illegal kickbacks to employees of labs or medical offices who could choose which supplier was used.

“The most direct way to satisfy [Rule 9(b)] is by identifying specific claims submitted to the government: invoices, billing records, reimbursement forms,” wrote Senior U.S. Circuit Judge Gerald Bard Tjoflat. Alternative means (other than documentary proof) may satisfy Rule 9(b), the court noted, as long as the claim has “sufficient indicia of reliability”—a case-by-case determination.

Reliability and Falsity

The Eleventh Circuit concluded that the relators successfully pleaded specific allegations relating to the CPAP accessory scheme. The court rejected the defendants’ arguments that: (1) there were insufficient indicia of reliability to show that an actual claim was submitted, and (2) even if claims were submitted, they were not false. On these points, the court determined the following:

Reliability: The relators adequately alleged hands-on access to private records, including patient files, billing correspondence, and authorizations for payment—“the type of inside information that [is] sufficient at the pleading stage.” The relators identified specific claims (i.e., specific instances of upcoding), with dates, amounts, and billing codes.

Falsity: The relators adequately alleged that the coding practices were improper and the resulting claims were false. Though the defendants claimed that TRICARE allowed the substitute ventilator codes, this was a factual dispute and not grounds for dismissal, per the court.

Meanwhile, the relators identified no specific false claims submitted to TRICARE in connection with: (1) any co-pay waiver, (2) the auto-ship scheme involving CPAP replacement supplies, or (3) the alleged kickbacks.

No Shotgun Pleadings

In a separate concurrence, Judge Tjoflat called attention to a “foundational pleading defect that the District Court did not reach.” The relators’ fourth amended complaint, he noted, packed all four of the fraud claims described above into a single count—burdening the courts, defendants, and the appellate process.

“That is not how litigation works,” he wrote. “The fourth amended complaint is a shotgun pleading—something we have condemned time and time again. It…forces courts to play detective rather than umpire.”

Shotgun pleadings, the judge stated, run counter to Rule 8 (requiring statements in a claim to be “short and plain,” with allegations that are “simple, concise, and direct”) and Rule 10 (requiring each claim founding on a separate transaction or occurrence to be stated in a separate count, “if doing so would promote clarity”). When confronted with a shotgun complaint, he said, a defendant should move for a more definite statement under Rule 12(e). And a district court should sua sponte strike it—“early and firmly.”

Takeaways

The Vargas decision offers clarity in the Eleventh Circuit on the rigorous application of the Rule 9(b) “reliable indicia” standard in the FCA context. With this decision, the Eleventh Circuit has made clear that merely alleging fraudulent schemes or practices is not enough to survive a Rule 9(b) challenge. Relators must allege concrete details connecting alleged schemes to actual false claims submitted to the government. Failure to do so is likely to result in dismissal. As demonstrated in Vargas, the Eleventh Circuit’s strict application of the standard underscores the high bar that relators must clear to avoid dismissal at the pleading stage.

Epstein Becker Green Staff Attorney Ann W. Parks contributed to the preparation of this post.

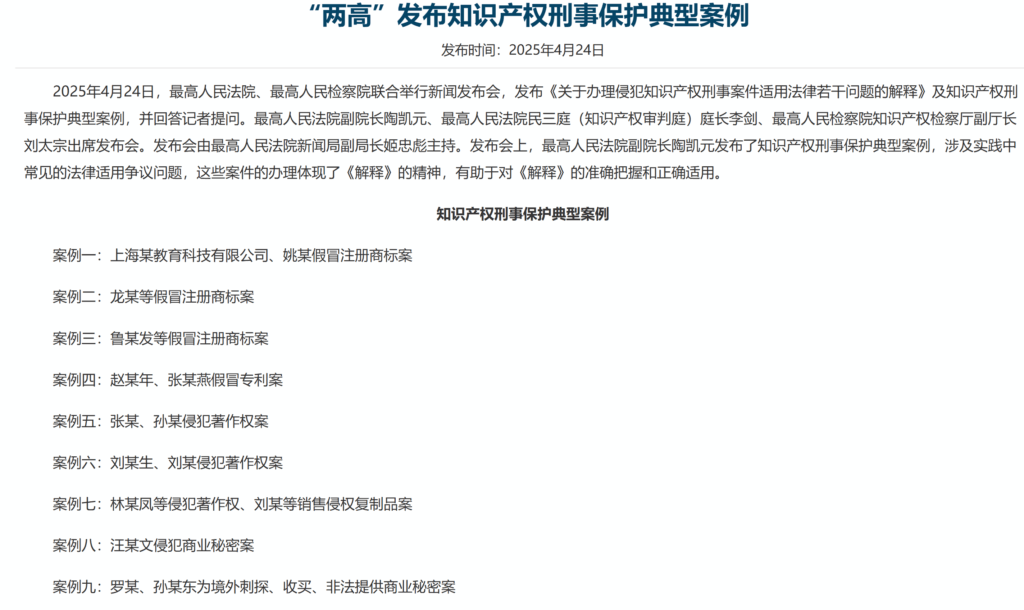

China’s Supreme People’s Court and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate Release Typical Cases of Criminal IP Enforcement for 2024

On April 24, 2025, China’s Supreme People’s Court (SPC) and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate (SPP) released the Typical Cases of Criminal IP Enforcement for 2024 (知识产权刑事保护典型案例). This batch was released to show how the newly-issued Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate on Several Issues Concerning the Application of Law in Handling Criminal Cases of Infringement of Intellectual Property Rights applies in criminal cases. This batch involves several foreign IP owners including Lego and Universal Studios. In addition, two criminal trade secret theft cases made the list.

As jointly explained by the SPP and SPC:

Case 1

Case of Shanghai XX Education Technology Co., Ltd. and Yao XX counterfeiting registered trademarks

【Basic Facts】

Lego and “LEGO Education” are registered trademark of Lego Co., Ltd., and the approved services are education, training, entertainment competitions, etc. The defendant, Shanghai XX Education Technology Co., Ltd., rented a store to operate the “LC Lego Robot Center”, and the defendant Yao was the actual operator of the company. From March to June 2021, Yao displayed the authorization letters, Lego Education coach qualification certificates and other documents purchased from others that counterfeited the registered trademarks of ” Lego” ” and “LEGO Education”, and used ” Lego” and other logos for store signs, decorations, posters, employee clothing, shopping mall signs, etc., to provide education and training services. Shanghai XX Education Technology Co., Ltd. collected more than 510,000 RMB in training course fees, most of which was used by the company.

[Judgment Result]

The Third Branch of the Shanghai People’s Procuratorate accused the defendant Shanghai XX Education Technology Co., Ltd. and the defendant Yao of the crime of counterfeiting registered trademarks and filed a public prosecution with the Shanghai Third Intermediate People’s Court. After trial, the Shanghai Third Intermediate People’s Court held that Shanghai XX Education Technology Co., Ltd. used the same trademark as the registered trademark on the same service without the permission of the registered trademark owner, and Yao was the directly responsible supervisor of the unit, both of which constituted the crime of counterfeiting registered trademarks, and therefore sentenced them to punishment.

【Typical significance】

The “Amendment to the Criminal Law of the People’s Republic of China (XI)” amended Article 213 of the Criminal Law, bringing the counterfeiting of registered service trademarks into the scope of regulation of the Criminal Law, and strengthening the criminal protection of registered trademarks. In this case, it was determined that the education and training services provided by the defendant unit and the services approved for use by the service registered trademark of the right holder were the same type of services, and the training fees collected by the defendant unit were used as the basis for conviction, which was in line with the provisions of the Criminal Law. The “Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate on Several Issues Concerning the Application of Laws in Handling Criminal Cases of Infringement of Intellectual Property Rights” further clarified the identification standards for “the same type of service” based on the actual situation such as the characteristics of the service industry, stipulated that the amount of illegal income was the standard for conviction of the crime of counterfeiting registered service trademarks, and further clarified that the service fees collected by the perpetrators were illegal income.

Case 2

Long et al. counterfeit registered trademark case

【Basic Facts】

The products approved for use by Rong’s registered trademark are “medical isolation gowns, surgical gowns”, etc. From December 2021 to January 2022, the defendants Long, Gao, Chen, Yuan, and Zeng, after planning, purchased protective clothing and packaging materials without the permission of Rong, the registered trademark owner, and packaged disposable medical protective clothing on their own, and sold them with Rong’s registered trademark attached. Among them, Long was responsible for contacting to purchase packaging materials, Gao, Chen, and Yuan were responsible for purchasing protective clothing, Yuan also provided an account for collecting payments, Zeng contacted private factories for OEM production of counterfeit medical protective clothing, and hired workers to package protective clothing. Long and others sold more than 40,000 sets of disposable medical protective clothing, with an illegal business amount of more than 580,000 RMB.

[Judgment Result]

The People’s Procuratorate of Nanchang High-tech Industrial Development Zone, Jiangxi Province, accused the defendant Long and others of the crime of counterfeiting registered trademarks and filed a public prosecution with the People’s Court of Nanchang High-tech Industrial Development Zone. After trial, the People’s Court of Nanchang High-tech Industrial Development Zone held that the goods “disposable medical protective clothing” and “medical isolation clothing and surgical clothing” approved for the registered trademarks are basically the same in terms of product functions, uses, main raw materials, consumer objects, sales channels, etc., and the relevant public believes that they are the same kind of goods, which belongs to the “same kind of goods” stipulated in Article 213 of the Criminal Law. Long and others used the same trademark as the registered trademark on the same kind of goods without the permission of the registered trademark owner, which constituted a joint crime, and the amount of illegal business was more than 580,000 RMB, which constituted the crime of counterfeiting registered trademarks, and were sentenced to punishment.

【Typical significance】

The identification of “the same kind of goods” is a difficult issue in handling criminal cases involving counterfeit registered trademarks. In practice, when the name of the goods produced and sold by the perpetrator is different from the name of the goods approved for use by the registered trademark of the right holder, if the two are the same or basically the same in terms of function, purpose, main raw materials, consumer objects, sales channels, etc., and the relevant public generally believes that they are the same kind of goods, they should be identified as “the same kind of goods”. In this case, the infringing goods and the goods approved for use by the registered trademark of the right holder are “the same kind of goods” in accordance with the law, and the defendants were accurately sentenced according to the law based on their roles in the joint crime, effectively cracking down on the illegal and criminal acts of manufacturing and selling counterfeit medical products. The “Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate on Several Issues Concerning the Application of Laws in Handling Criminal Cases of Infringement of Intellectual Property Rights” further clarifies the identification standards of “the same kind of goods” based on actual conditions. In addition, in order to accurately crack down on crimes of infringement of intellectual property rights in accordance with the law, the judicial interpretation clarifies the specific circumstances in which joint crimes are punished.

Case 3

Case of Lu XX et al. counterfeiting registered trademarks

【Basic Facts】

From November 2019 to August 2022, the defendant Lu XX and others, without the permission of the registered trademark right holder, commissioned others to produce trademarks such as “HARRY POTTER” and “UNIVERSAL STUDIOS”, and produced magic robes, scarves, ties and other Universal Studios Harry Potter products with the above trademarks through self-processing, sewing and labeling, and then sold them, with an illegal business amount of more than 11.25 million RMB. The public security organs seized 25,730 counterfeit registered trademark products and 72,550 hang tags, collar labels, washing labels, etc. in the premises operated by Lu XX.

[Judgment Result]

The People’s Procuratorate of Tongzhou District, Beijing, accused the defendant Lu XX and others of the crime of counterfeiting registered trademarks and filed a public prosecution with the People’s Court of Tongzhou District, Beijing. The People’s Court of Tongzhou District, Beijing held that the registered trademark owner registered trademarks such as “HARRY POTTER” and “UNIVERSAL STUDIOS”, and the alleged infringing mark added elements that lacked distinctive features after “UNIVERSAL STUDIOS”, which did not affect the distinctive features of the registered trademark and was an “identical trademark”. Lu XX and others used trademarks identical to their registered trademarks on the same kind of goods without the permission of the registered trademark owner, which constituted the crime of counterfeiting registered trademarks and were sentenced to punishment.

【Typical significance】

In order to further combat the crime of counterfeiting registered trademarks and unify and clarify the identification standards of “identical trademarks”, the “Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate on Several Issues Concerning the Application of Laws in Handling Criminal Cases of Intellectual Property Infringement” clarified the identification standards of identical trademarks. In this case, the addition of elements lacking distinctive features to the alleged infringing mark does not affect the distinctive features of the registered trademark and should be identified as a trademark identical to the registered trademark, demonstrating the concept of strict intellectual property protection.

Case 4

Zhao XX and Zhang XX’s patent counterfeiting case

【Basic Facts】

The defendants Zhao XX and Zhang XX run a biotechnology company. Since 2021, the two have printed the invention patent number of a Chinese medicine research company’s “A method for preparing a purslane extract” on the cosmetics packaging produced by their company without the permission of the Chinese medicine research company, and sold cosmetics that counterfeit the above patent. Zhao and Zhang sold counterfeit cosmetics with the above patent for more than 990,000 RMB, and the value of the counterfeit cosmetics with the above patent that have not yet been sold is more than 570,000 RMB, and the total amount of illegal business is more than 1.56 million RMB.

[Judgment Result]

The People’s Procuratorate of Baiyun District, Guangzhou City, Guangdong Province, accused the defendants Zhao and Zhang of patent counterfeiting and filed a public prosecution with the Baiyun District People’s Court of Guangzhou City. After trial, the Baiyun District People’s Court of Guangzhou City held that Zhao and Zhang had been operating a cosmetics production company for many years. They knew that the use of patent marks or patent numbers should be authorized by the patent owner, but they still marked other people’s patent numbers on the product packaging without the permission of the patent owner, misleading the public into believing that the cosmetics were patented products. This was an act of “counterfeiting other people’s patents” and the circumstances were serious, constituting the crime of patent counterfeiting, and therefore sentenced them to punishment.

【Typical significance】

The crime of patent counterfeiting regulates the act of counterfeiting other people’s patents without the permission of the patent owner. Falsely marking other people’s patent numbers to mislead the public into believing that the products sold are legally produced and manufactured by the patent subject damages the legitimate rights and interests of the patent owner and disrupts the market economic order. If the circumstances are serious, criminal liability shall be pursued in accordance with the law. The “Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate on Several Issues Concerning the Application of Laws in Handling Criminal Cases of Intellectual Property Infringement” clarifies the specific circumstances of counterfeiting other people’s patents and the standard for “serious circumstances” to strengthen criminal protection of patents.

Case 5

Copyright infringement case of Zhang and Sun

【Basic Facts】

Between the end of 2017 and January 2023, the defendants Zhang and Sun, etc., developed and operated a number of film and television aggregation apps for the purpose of profit. Zhang, Sun, etc. downloaded popular audiovisual works without the permission of the copyright owner and uploaded them to a rented cloud storage server, and purchased technical analysis services from others, and provided audiovisual works playback and download services to the public through the multiple apps they operated. Through the technical analysis service, the public can obtain the audiovisual works from the above-mentioned multiple apps involved in the case without jumping to the network platform of the relevant copyright owner. Zhang, Sun, etc. made profits by publishing paid advertisements and collecting advertising promotion fees in the multiple apps involved in the case. Among them, Zhang, Sun, etc. disseminated more than 72,000 audiovisual works through “hotlinking”.

[Judgment Result]

The People’s Procuratorate of Xinwu District, Wuxi City, Jiangsu Province, accused the defendants Zhang and Sun of copyright infringement and filed a public prosecution with the People’s Court of Xinwu District, Wuxi City. The People’s Court of Xinwu District, Wuxi City held that Zhang and Sun objectively made the relevant audiovisual works directly appear on the multiple apps involved in the case by “stealing links”, which was an act of “providing” works. The public was able to obtain the above-mentioned audiovisual works from the multiple apps involved in the case at a time and place selected by individuals and directly play and download them, infringing the copyright owner’s right to disseminate through information networks, which was an act of “disseminating to the public through information networks” as stipulated in Article 217 of the Criminal Law. Zhang and Sun disseminated audiovisual works to the public through information networks for the purpose of profit without the permission of the copyright owner, which constituted the crime of copyright infringement and were sentenced to punishment.

【Typical significance】

The “Amendment to the Criminal Law of the People’s Republic of China (XI)” clearly stipulates that “dissemination to the public through information networks” is an implementation behavior, which is distinguished from “copying and distributing”. Without the permission of the copyright owner, “dissemination to the public through information networks” infringes the copyright owner’s information network dissemination right. According to the “Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate on Several Issues Concerning the Application of Laws in Handling Criminal Cases of Infringement of Intellectual Property Rights”, if a person provides works, audio and video products, and performances to the public by wire or wireless means without permission, so that the public can obtain them at the time and place of their choice, it shall be deemed as “dissemination to the public through information networks” as stipulated in Article 217 of the Criminal Law. With the emergence of new technologies in the field of information dissemination, more and more technologies similar to “hotlinking” can avoid the link of uploading works, allowing users to obtain corresponding works, which is very harmful to society. Based on the specific methods of “hotlinking” and its social harm, this case is determined to be an information network dissemination behavior, which infringes the copyright owner’s information network dissemination right, which is conducive to accurately defining the nature of deep linking behaviors such as “hotlinking.”

Case 6

Liu XX’s and Liu YY’s copyright infringement case

【Basic Facts】

From March 2019 to July 2022, the defendant Liu XX, for the purpose of profit, without the permission of the copyright owner, made dongles to circumvent the technical protection measures of copyright, copied related software without authorization, and sold dongles and pirated software. Liu XX also instructed the defendant Liu YY to sell dongles and pirated software. During this period, Liu XX was responsible for making the dongles, copying pirated software, putting goods on shelves, sending express delivery, etc., and Liu YY was responsible for account customer service, collection, etc. The illegal business amounts involved by Liu XX and Liu YY were more than 1.06 million RMB and more than 140,000 RMB, respectively. The dongles sold by Liu XX and Liu YY can circumvent the technical protection measures taken by the copyright owner for their software copyrights.

[Judgment Result]

The Third Branch of the Shanghai People’s Procuratorate accused the defendants Liu XX and Liu YY of copyright infringement and filed a public prosecution with the Third Intermediate People’s Court of Shanghai. The Third Intermediate People’s Court of Shanghai held that Liu XX and Liu YY, for the purpose of profit, deliberately circumvented the technical measures taken by the copyright owner to protect the copyright for their works without the permission of the copyright owner. In particular, Liu Sheng produced and sold dongles and pirated software, etc., and was at the source of the industrial chain in the relevant series of cases. The act of providing devices to circumvent technical measures has great social harm. Liu XX’s circumstances are particularly serious, and Liu YY’s circumstances are serious. Both of them have committed the crime of copyright infringement and were sentenced to punishment.

【Typical significance】

The “Amendment to the Criminal Law of the People’s Republic of China (XI)” includes the act of circumventing technological measures in the scope of regulation of the crime of copyright infringement, further strengthening the criminal protection of copyright. The social harm caused by providing devices for circumventing technological measures is great, and it is a criminal act stipulated in the Criminal Law. In this case, Liu XX and Liu YY were held criminally responsible for the crime of copyright infringement in accordance with the law, fully protecting the legitimate rights of copyright owners, and demonstrating the strength and determination to strengthen criminal judicial protection of intellectual property rights and serve the innovative development of the digital economy. The “Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate on Several Issues Concerning the Application of Law in Handling Criminal Cases of Intellectual Property Infringement” clearly stipulates that the act of intentionally providing devices, components, and technical services for circumventing technological measures constitutes the crime of copyright infringement.

Case 7

Case of Lin XX et al. infringing copyright and Liu XX et al. selling infringing copies

【Basic Facts】

From 2019 to February 2023, the defendant Lin and others copied and distributed “scripted murder game” works by scanning, typesetting, printing and other means without the permission of the copyright owner, and the illegal business amount was more than 5.4 million RMB. The defendants Liu, Yang XX, and Yang YY knew that the “scripted murder games” sold by Lin and others were infringing copies without the permission of the copyright owner, but they still purchased them and sold them to the outside. Among them, Liu’s sales amount was more than 7.38 million RMB, and Yang XX’s and Yang YY’s sales amount was more than 3.12 million RMB.

[Judgment Result]

The People’s Procuratorate of Nanhu District, Jiaxing City, Zhejiang Province, accused the defendant Lin and others of copyright infringement, and the defendants Liu , Yang XX, and Yang YY of selling infringing copies, and filed public prosecutions with the Nanhu District People’s Court of Jiaxing City. The Nanhu District People’s Court of Jiaxing City held that Lin and others, for the purpose of profit, copied and distributed literary works and works of art without the permission of the copyright owner, which constituted copyright infringement; Liu, Yang XX, and Yang YY sold infringing copies, which constituted the crime of selling infringing copies, and sentenced them to punishment.

【Typical significance】

The “Amendment to the Criminal Law of the People’s Republic of China (XI)” has amended the provisions for the crime of selling infringing copies, and changed “huge illegal proceeds” to “huge illegal proceeds or other serious circumstances”, expanding the circumstances for conviction. In order to further crack down on illegal and criminal acts of copyright infringement and improve the standards for conviction, the “Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate on Several Issues Concerning the Application of Laws in Handling Criminal Cases of Intellectual Property Infringement” stipulates that “sales amount”, “value of goods” and “number of copies” are “other serious circumstances.” In order to further distinguish between the crime of copyright infringement and the crime of selling infringing copies, the judicial interpretation clarifies that the “copying and distribution” in the crime of copyright infringement does not include the simple “distribution” behavior. Distributing infringing copies made by others by selling them should be deemed as the crime of selling infringing copies. This series of cases was convicted and sentenced for the crime of copyright infringement and the crime of selling infringing copies according to the specific acts committed by each defendant, which is in line with the spirit of the judicial interpretation.

Case 8

Case of Wang XX infringing on trade secrets

【Basic Facts】

From April 2020 to April 2021, the defendant Wang worked in a certain automobile company in Wuhu. On March 23, 2021, Wang was preparing to switch to a new energy automobile company in Zhejiang to engage in electrical appliance research and development. In order to bring the switch control technology of a certain automobile company in Wuhu to a certain new energy automobile company in Zhejiang, on the evening of April 4, 2021, Wang dismantled the computer hard disk of the leaders of Group 1 and Group 2 of the Intelligent Vehicle Technology Center of a certain automobile company in Wuhu, which he had no authority to view, and took it away, and uploaded the technical information of the “center console switch assembly” and “one-button start ” of a certain model of automobile switch system in the computer hard disk to his own Baidu cloud account. After evaluation, the reasonable license fee for the above two technical information is 1.14 million RMB.

[Judgment Result]

The People’s Procuratorate of Wuhu Economic and Technological Development Zone, Anhui Province, accused the defendant Wang of violating trade secrets and filed a public prosecution with the People’s Court of Wuhu Economic and Technological Development Zone. The People’s Court of Wuhu Economic and Technological Development Zone held that the technical information contained in the technical drawings of the “center console switch assembly” and “one-button start ” in the switch system of a certain model of a certain automobile company in Wuhu was a trade secret. Wang obtained trade secrets by dismantling and taking away the computer hard drive, which was an act of obtaining trade secrets by improper means of theft. The amount of loss can be determined according to the reasonable license fee of the trade secret. The circumstances were serious and constituted the crime of violating trade secrets, so he was sentenced to punishment.

【Typical significance】

The “Amendment to the Criminal Law of the People’s Republic of China (XI)” changed the standard for conviction of the crime of infringing on trade secrets from “causing major losses to the rights holder of the trade secrets” to “serious circumstances”, increasing the criminal protection of trade secrets. The person who obtains trade secrets by improper means does not have legal knowledge or possession of the trade secrets before, and his act of obtaining trade secrets by improper means is itself illegal and should be severely punished. If a trade secret is obtained by improper means, the amount of loss of the rights holder can be determined according to the reasonable license fee of the trade secret, and it is not required to use the trade secret for production and operation to cause profit loss. In this case, according to the provisions of the Criminal Law, Wang’s behavior was determined to be “serious circumstances” and he was sentenced in accordance with the law, demonstrating the strict protection of innovative achievements. The “Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate on Several Issues Concerning the Application of Laws in Handling Criminal Cases of Infringement of Intellectual Property Rights” further clarified the standard for determining “serious circumstances..

Case 9

Case of Luo XX and Sun XX spying, buying and illegally providing commercial secrets an overseas entity

【Basic Facts】

In August 2022, the defendant Sun accepted the commission of a foreign person and provided him with commercial information on new energy batteries of a certain technology company for a fee. After Sun discussed with the defendant Luo, Luo obtained the company’s new energy battery research and development data, future industrial layout and other commercial information from relevant personnel of a certain technology company through illegal means such as espionage and bribery, and Sun provided it to the foreign person. Sun received a remuneration of more than 110,000 RMB, of which 70,000 RMB was paid to Luo . In April 2023, Luo directly accepted the commission of the foreign person and again provided commercial information of a certain technology company and received a remuneration of 100,000 RMB.

[Judgment Result]

The People’s Procuratorate of Yinzhou District, Ningbo City, Zhejiang Province, accused the defendants Luo and Sun of spying, buying, and illegally providing commercial secrets for foreign countries, and filed a public prosecution with the People’s Court of Yinzhou District, Ningbo City. After trial, the People’s Court of Yinzhou District, Ningbo City held that the new energy battery research and development data and future industrial layout information illegally provided by Sun and Luo to foreign personnel were commercial secrets, and Luo and Sun constituted the crime of spying, buying, and illegally providing commercial secrets for foreign countries, and sentenced them to punishment.

【Typical significance】

In order to maintain a fair and competitive market economic order, the “Criminal Law Amendment (XI) of the People’s Republic of China” adds the crime of stealing, spying, buying, and illegally providing trade secrets from abroad, improves the criminal law network, and strengthens the criminal protection of trade secrets. This crime is a behavioral crime, and criminal liability can be pursued without requiring the circumstances to be serious. The “Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate on Several Issues Concerning the Application of Law in Handling Criminal Cases of Infringement of Intellectual Property Rights” stipulates the specific circumstances of the “serious circumstances” for the sentencing standard of this crime, which is consistent with the circumstances of conviction for the crime of infringing trade secrets, etc., to ensure the effective connection between the conviction and sentencing of the two crimes.

An AI Whistleblower Bill is Urgently Needed

Last year, thirteen brave AI whistleblowers issued a letter titled “A Right to Warn about Advanced Artificial Intelligence,” risking retaliation for highlighting rampant concerns around internal safety and security protocols on products that are built shielded from proper oversight being released to and unleashed upon the public. Legislation is needed to help workers responsibly report the development of high-risk systems that is currently occurring without appropriate transparency and oversight.

The concerns of these AI whistleblowers, in combination with the documented attempts of AI companies to stifle whistleblowing, underscore the urgent need for Congressional action to pass a best-practices whistleblower bill that specifically addresses AI employees.

Like the powerful developing sectors preceding it, insiders in the Artificial Intelligence industry do not have explicit access to safeguards for reporting until legislation is passed. There is historical precedent for sector-based protections: Congress has enacted whistleblower protection laws in past decades that covered employees across relevant industries, including nuclear energy in the 1978 Energy Reorganization Act, airlines under AIR21 in 2000, the federal government in the 1989 Whistleblower Protection Act, and Wall Street under Dodd-Frank in 2010. This legislation helps ensure that workers in such specified fields are able to speak out on issues endangering the public. As its emergence in popular consciousness is recent — ChatGPT was initially released November of 2022 — legislation is behind technological advancement, with executives urging legislators to employ “light touch” regulation. Employees working for AI companies are left without any specialized whistleblower protections.

Why We Need an AI Whistleblower Bill

The whistleblowers’ letter cited public claims from leading scholars, advocates, experts and AI companies themselves pointing to the significant potential harms of AI technology when released into the market without the proper safety protocols. These concerns included further entrenchment of existing inequalities, media manipulation and misinformation, and loss of control of autonomous AI systems. These companies themselves have even published reports on their models’ concerning and risky behavior, but continue to deploy their products for public, business, government, and military use. Specific points the group noted last year that companies, governments, and advocacy groups have made on the matter include:

Serious risk of misuse, drastic accidents, and societal disruption … we are going to operate as if these risks are existential (OpenAI)

Toxicity, bias, unreliability, dishonesty (Anthropic)

Offensive cyber operations, deceive people through dialogue, manipulate people into carrying out harmful actions, develop weapons (e.g. biological, chemical) (Google DeepMind)

Exacerbate societal harms such as fraud, discrimination, bias, and disinformation; displace and disempower workers; stifle competition; and pose risks to national security (US Government – White House)

Further concentrate unaccountable power into the hands of a few, or be maliciously used to undermine societal trust, erode public safety, or threaten international security … [AI could be misused] to generate disinformation, conduct sophisticated cyberattacks or help develop chemical weapons (UK Government – Department for Science, Innovation & Technology)

Inaccurate or biased algorithms that deny life-saving healthcare to language models exacerbating manipulation and misinformation (Statement on AI Harms and Policy (FAccT))

Algorithmic bias, disinformation, democratic erosion, and labor displacement. We simultaneously stand on the brink of even larger-scale risks from increasingly powerful systems (Encode Justice and the Future of Life Institute)

Risk of extinction from AI…societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war (Statement on AI Risk (CAIS))

With guidance from the scientific community, policymakers, and the public, these risks can be adequately mitigated. However, AI companies have financial incentives to avoid effective oversight.

Also in 2024, whistleblowers brought to light broad confidentiality and non-disparagement agreements which were used to muzzle current and former employees from voicing their concerns. OpenAI whistleblowers filed a complaint with the SEC detailing that OpenAI utilized employment agreements which included:

Non-disparagement clauses that failed to exempt disclosures of securities violations to the SEC;

Requiring prior consent from the company to disclose confidential information to federal authorities;

Confidentiality requirements with respect to agreements, that themselves contain securities violations;

Requiring employees to waive compensation that was intended by Congress to incentivize reporting and provide financial relief to whistleblowers.

While OpenAI claims to have addressed its non-disclosure agreements, the chilling effect of these threats remains in company culture. It is highly concerning that OpenAI whistleblowers with inside knowledge on what oversight is needed have no explicit legal federal protections whatsoever. As it stands, a whistleblower working for major AI companies could be fired for raising concerns around issues such as venues for misuse, internal and external security concerns.

Without information from whistleblowers, the ability of the U.S. government to police and regulate this newly developing technology is curtailed, risking heightening the technology’s risks to public health, safety, national security, and more. Insiders must be able to disclose potential violations safely, freely, and appropriately to law enforcement and regulatory authorities.

What an AI Whistleblower Bill Needs to Include

Legislation must send the message to the AI industry, and to the tech industry at large, that violations on the right of employees to report wrongdoing will not be tolerated. Potential whistleblowers at AI companies must have comprehensive avenues to report even potential violations, instances of misconduct, and safety issues occurring throughout the field. Effective whistleblower laws require that such complaints be welcomed and rewarded as a matter of law and policy, not discouraged by companies sending direct or indirect messages to employees that chill their speech that has resulted in so many catastrophes in the past.

It is critical that an AI whistleblower law pass through the 119th Congress. Any such law must follow the solid precedents used in recent whistleblower legislation that has been passed, either unanimously or without any controversy, by Congress. The most recent example of a private sector whistleblower law that incorporated the basic due process requirements necessary to protect whistleblowers was the Taxpayer First Act, 26 U.S. Code § 7623(d). This law includes the following basic procedures, all of which need to be incorporated into any AI whistleblower law:

Due Process Protections: This includes the right to file a retaliation case in federal court and a jury trial, if requested.

Protection Against Retaliation: Anti-retaliation language that establishes that no employer, individual, or agent of an employer may fire, demote, blacklist, threaten, discriminate or harass an employee/former employee/applicant for employment and/or contractor who has engaged in protected activities covered under the law, which would include providing truthful information to state or federal law enforcement or regulatory authorities.

Appropriate Damages: A whistleblower who prevails in a retaliation case must be afforded a full “make whole” remedy, including (but not limited to) reinstatement and restoration of all of the privileges of his or her prior employment, back pay, front pay, compensation for lost benefits, compensatory damages, special damages, and all attorney fees, costs, and expert witness fees reasonably incurred. Some laws also provide double back pay or punitive damages, which should also be considered. Moreover, a court must have explicit jurisdiction to afford all equitable relief, including preliminary relief.

An Adequate Definition of a Protected Disclosure: Protected whistleblower disclosures should cover reports made, both internally to corporations and to other appropriate authorities, including Congress, and/or state law enforcement or regulatory authorities. Disclosures covered should include reporting threats AI may pose to national security, public health and safety, and financial frauds.

Anonymous and confidential reporting to a company’s internal compliance program.

Prohibition against contractual restrictions on the right to blow the whistle, including barring of mandatory arbitration agreements that would restrict an employee from filing a complaint under the whistleblower law.

No federal preemption or interference with the right to file claims under other state or federal law.

Modern anti-fraud and public safety laws uniformly include whistleblower protections similar to those outlined above. These include the laws such as the aforementioned Taxpayer First Act, as well as the Food Safety Modernization Act, Sarbanes-Oxley Act, the Anti-Money Laundering Act, and the National Transportation Security Act. Given the potential threats posed by AI, how companies have mishandled deployment, and the importance that emerging AI technology is safely developed, there is an urgent need for insiders working in the AI sector to be properly protected when they lawfully report threats to the public interest.

Charges Dropped Against Early Cryptocurrency Exchange Operator

Go-To Guide:

In early 2025, a federal judge dismissed charges against an Indiana businessman for failure to register his cryptocurrency exchange platform with Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN).

In doing so, the court noted that FinCEN had not put the industry on notice that cryptocurrency businesses could be subject to the registration requirement until late 2013, after the core time period at issue in the indictment.

Although the Department of Justice (DOJ) immediately appealed the decision, it later withdrew its appeal and voluntarily dismissed all proceedings against the defendant on April 23.

This dismissal of charges against an early cryptocurrency exchange operator follows DOJ’s recent announcement of a nationwide shift in its approach to digital asset enforcement.

In late April, at the government’s request, an Indiana federal judge put a final end to the prosecution of an Indiana man for allegations that he engaged in unlicensed money transmission (and related tax offenses) in connection with his operation of a virtual currency exchange from 2009 to 2013.1 The case represents a relatively rare instance in which a court granted a pretrial motion to dismiss charges related to unlicensed money transmission, although the impact of the decision may be limited to cases from 2013 and earlier—the year that FinCEN issued key guidance on the topic. The case has also attracted attention for what it may signal about DOJ’s digital asset enforcement priorities.

United States v. Pilipis

In early 2024, federal prosecutors in Indiana charged Maximiliano Pilipis with money laundering and willful failure to file tax returns, based on allegations that, from 2009 to 2013, Pilipis operated cryptocurrency exchange platform AurumXchange that was required to, but did not, register as a money transmitting business.

The Bank Secrecy Act requires money transmitters to register with FinCEN, and 18 U.S.C. § 1960 makes it a crime, among other things, to knowingly operate an unregistered money transmitting business. In 2013 and again in 2019, FinCEN issued guidance to clarify that the definition of money transmitter includes those who make a business of accepting, exchanging, and transmitting virtual currencies such as Bitcoin. And Congress, in the Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020, codified the extension of money transmission to any transfers of “value that substitutes for currency.”2 Notably, however, the conduct at issue in the Pilipis indictment predated that guidance and legislation.

In a motion to dismiss the indictment, Pilipis argued that the government already investigated AurumXchange 14 years ago and did not identify any wrongdoing. He also argued that at the time his business was operational, the legal framework surrounding virtual currencies was ambiguous, and prior to March 2013, it was unclear whether entities like AurumXchange were even required to register with FinCEN.

In February 2025, the court dismissed the money laundering counts to the extent they were predicated on a violation of § 1960 prior to the issuance of the 2013 FinCEN guidance, concluding that AurumXchange had no obligation to register with FinCEN prior to that guidance. The court allowed the tax charges to proceed and also indicated that there was a fact issue about whether any of the alleged money laundering conduct post-dated the 2013 FinCEN guidance and might therefore state a viable offense.

DOJ appealed the dismissal order to the Seventh Circuit in late February 2025, but later withdrew its appeal and moved to dismiss both the criminal case and a related civil forfeiture case on April 23, 2025. Judge Magnus-Stinson granted that motion and dismissed the criminal and civil cases with prejudice the same day.

The move follows an April 7, 2025, memorandum issued by U.S. Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche, which announced that DOJ will “no longer pursue litigation or enforcement actions that have the effect of superimposing regulatory frameworks on digital assets while President Trump’s actual regulators do this work outside the punitive criminal justice framework.” Among other things, the memorandum directed prosecutors not to charge “regulatory violations in cases involving digital assets,” including “unlicensed money transmitting under 18 U.S.C. § 1960(b)(l)(A) and (B)… unless there is evidence that the defendant knew of the licensing or registration requirement at issue and violated such a requirement willfully.” Takeaways

Virtual currency businesses and other early adopters of emerging technologies have been subject to a certain degree of legal uncertainty for some time, as laws and regulations struggle to keep up with the pace of innovation. In this instance, the district court declined to apply regulatory guidance retroactively, and the DOJ abandoned its enforcement efforts.

Members of the digital assets community should continue to monitor developments in this space in light of the administration’s approach to digital asset regulation and enforcement. However, even if the DOJ may be limiting the types of enforcement cases it will bring against digital asset firms, it may continue to prosecute cases that reflect the administration’s priorities (e.g., fraud, money laundering, and sanctions violations). In addition, state enforcement activity is continuing to date and may increase.

1 United States v. Pilipis, Case No. 1:24-cr-00009-JMS-MKK.

2 Pub. L. No. 116–283 § 6201(d), codified at 31 U.S.C. § 5330(d)(1)(A) (eff. Jan. 1, 2021).

Paint It White: No Sovereign Immunity in Economic Espionage Case

The US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit affirmed a district court’s denial of foreign sovereign immunity to a Chinese company accused of stealing trade secrets related to the production of proprietary metallurgy technology. United States v. Pangang Grp. Co., Ltd., Case No. 22-10058 (9th Cir. Apr. 29, 2025) (Wardlaw, Collins, Bress, JJ.)

Pangang is a manufacturer of steel, vanadium, and titanium. E.I. du Pont de Nemours (DuPont) had a proprietary chloride-route technology used for producing TiO₂, a valuable white pigment used in paints, plastics, and paper. Pangang allegedly conspired with others to obtain DuPont’s trade secrets related to TiO₂ production through economic espionage in order to use the stolen information to start a titanium production plant in China. The US government filed a criminal lawsuit.

In defense, Pangang invoked the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA) and federal common law, arguing that it was entitled to foreign sovereign immunity from criminal prosecution in the United States because it was ultimately owned and controlled by the government of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). In a prior appeal, the Ninth Circuit had found that Pangang failed to make a prima facie showing that it fell within the FSIA’s domain of covered entities. On remand, the district court again rejected Pangang’s remaining claims of foreign sovereign immunity, including its claims based on federal common law.

While the appeal was pending, the Supreme Court’s 2023 decision in Turkiye Halk Bankasi v. United States clarified that common law, not the FSIA, governs whether foreign states and their instrumentalities are entitled to foreign sovereign immunity from criminal prosecution in US courts. This led to a rebriefing of the present appeal to focus on the now-controlling issues concerning the extent to which Pangang enjoys foreign sovereign immunity under federal common law. Under federal common law, an entity must satisfy two conditions to enjoy foreign sovereign immunity from suit:

It must be the kind of entity eligible for immunity.

Its conduct must fall within the scope of the immunity conferred.

The Ninth Circuit concluded that Pangang did not make a prima facie showing that it exercised functions comparable to those of an agency of the PRC and therefore was not eligible for foreign sovereign immunity from criminal prosecution. The Court also found that “[t]he mere fact that a foreign state owns and controls a corporation is not sufficient to bring the corporation within the ambit of [sovereign immunity].” Since Pangang’s commercial activities were not governmental functions, there was no evidence that sovereign immunity should be applied. Therefore, the Ninth Circuit affirmed the district court’s denial of the motion to dismiss based on sovereign immunity.

FINRA Facts and Trends: May 2025

FINRA’s Modernization Pitch: New Initiatives Aimed at Updating FINRA Rules and Easing Regulatory Burdens

On April 21, 2025, FINRA unveiled FINRA Forward, a broad review of its rules and regulatory framework that is intended to modernize existing rules regarding member firms and associated persons.

As part of its initiatives, FINRA is inviting significant engagement from industry members, seeking comments and feedback from member firms, investors, trade associations and other interested parties in an effort to update and adapt FINRA’s rules and regulatory standards to better suit the modern environment and the latest technologies used by member firms.

In a blog post, FINRA’s President and CEO, Robert Cook, wrote that FINRA “must continuously improve its regulatory policies and programs to make them more effective and efficient.”

FINRA has identified three goals of its FINRA Forward initiative: (1) modernizing FINRA’s rules; (2) empowering member firm compliance; and (3) combating cybersecurity and fraud risks. FINRA’s focus on modernizing rules will seek to eliminate unnecessary burdens on member firms, and to modernize requirements and facilitate innovation. With respect to compliance, FINRA aims to better protect investors and safeguard markets by enhancing the ways in which FINRA supports its member firms’ compliance efforts. Finally, FINRA is expanding its cybersecurity and fraud prevention activities.

The FINRA Forward initiatives were first previewed in Regulatory Notice 25-04, published on March 12, 2025, which identified two areas of initial focus for FINRA’s modernization effort: capital formation and the modern workplace. At the same time, FINRA requested comments for other areas FINRA should consider as part of its review. Following on the heels of Regulatory Notice 25-04, FINRA soon afterward published a series of more detailed Notices: Regulatory Notice 25-05, regarding associated persons’ outside activities; Regulatory Notice 25-06, which addresses capital formation; and Regulatory Notice 25-07, on the modern workplace.

We focus below on FINRA’s request for comments, in Regulatory Notice 25-07, on modernizing FINRA rules, guidance and processes for the organization and operation of member workplaces. This initiative promises a “broad rule modernization review” and “significant changes” to FINRA’s rules and regulatory framework “to support the evolution of the member workplace.” This modernization effort has the potential to significantly change regulatory compliance programs for virtually every FINRA member firm.

While noting that commenters “should not be limited by the topics and questions FINRA identifies,” FINRA has highlighted the following rules, guidance and processes on which it welcomes comments from industry members.

Branch Offices and Hybrid Work

FINRA is contemplating additional updates to FINRA Rule 3110 (the Supervisory Rule) in its continued effort to account for technological advances and hybrid working arrangements.

Just last year, FINRA amended Rule 3110 in response to changes in work arrangements, allowing members to designate eligible private residences as “residential supervisory locations” (RSLs) and to be treated as non-branch locations. FINRA also launched a voluntary, three-year pilot program that permits eligible members the flexibility to satisfy their inspection obligations under Rule 3110 without requiring an on-site visit to the office or location.

Now, in response to further feedback from members, FINRA is questioning whether the branch office and office of supervisory jurisdiction (OSJs) designations remain relevant in an age of digital monitoring, cloud-based systems and virtual meetings. Additionally, FINRA is asking if there are ways the Central Registration Depository (CRD) system and Form BR can be revised to “better align FINRA, other SRO and state requirements for broker-dealers with the uniform branch office definition and registration and designation of offices and locations.”

Registration Process and Information

Associated persons and member firms submit information to SROs and state and federal regulators through Uniform Registration Forms that communicate this information to FINRA’s CRD system. Notice 25-07 is now seeking comments on proposed changes to the process and systems currently in place to address modern technologies and workplaces, as well as the substance or presentation of the information provided to the public. These contemplated changes could impact such forms as Form BD and Forms U4 and U5.

Qualifications and Continuing Education

All securities professionals seeking registration must demonstrate the necessary qualifications by passing a standardized professional examination. After they are registered, these professionals are required to maintain their qualifications by completing a Continuing Education (CE) program that is designed to ensure that registered persons stay current as industry standards and rules evolve.

From time to time, FINRA has adapted its qualification and CE requirements to account for improvements in technology, learning theory and assessment methodologies. For example, in 2022 FINRA responded to the increased frequency of job changes and member restructures by implementing the Maintaining Qualifications Program (MQP) for individuals that have decided to temporarily step out of roles that require active registration. Members have taken advantage of the MQP since its launch in 2022, with approximately 38,000 individuals participating in or having participated in the program.

Now, FINRA is seeking input on further improving the CE program and exam framework to better serve the industry. Among other things, FINRA is asking whether registered persons should be allowed to take certain qualification exams without needing firm sponsorship. More generally, FINRA is also asking whether new technologies can be leveraged to identify appropriate candidates for positions that require registration and whether it should consider any changes to the CE and MQP to ensure that it is meeting the needs of its members.

Delivery of Information to Customers

As digital communication becomes the standard in customer engagement, FINRA is examining whether its existing rules on document delivery and account transfers still make sense in an increasingly paperless world.

The current rules, based on guidance issued decades ago, require firms to obtain informed customer consent before delivering documents electronically — an approach that can be cumbersome given how digitally savvy most investors now are. At the same time, rules around account transfers — especially those using “negative consent” (where the transfer proceeds unless the customer objects) — remain narrow, even though business needs often demand flexibility. For instance, when firms exit a business line or shift clearing arrangements, obtaining affirmative consent from every affected customer may be logistically impossible, creating risk and delay.

FINRA is now asking whether more flexible, principles-based standards should replace rigid prescriptive ones, particularly regarding negative consent scenarios. FINRA is also exploring whether its rules should be better aligned with those in the investment advisory world, where digital delivery and flexible account transfer protocols are more common. These questions are particularly relevant as firms use mobile apps, dynamic disclosures and automated notifications to streamline service. At the same time, FINRA must ensure that these innovations don’t compromise privacy, security or investor understanding. By opening this discussion, FINRA aims to support a future-ready regulatory environment where efficiency and investor protection go hand in hand.

Recordkeeping and Digital Communications

With the explosion of digital communication channels, broker-dealers face growing challenges in complying with recordkeeping requirements under both SEC Rule 17a-4 and FINRA rules. From emails and instant messages to Zoom meetings, AI chatbots, and interactive websites, the range of communications that may be deemed “business-related” has expanded dramatically.

“Off-channel” communications — messages sent through unauthorized apps or platforms — remain a major concern. These communications pose compliance and enforcement risks, and can lead to gaps in supervisory oversight. Similarly, as firms adopt generative AI tools for customer engagement or internal operations, questions arise about whether those communications need to be retained and how best to do so. For example, should chatbot responses or AI-generated meeting summaries be archived the same way as emails? What about dynamic content on websites that changes based on user behavior? The goal is to ensure that recordkeeping rules remain effective and clear in a multiplatform, mobile-first environment.

Rather than creating new obstacles to innovation, FINRA wants to promote best practices and enable compliance through thoughtful modernization. Member feedback will be vital in identifying pain points, sharing successful approaches following the recent off-channel communication enforcement actions by the SEC, and recommending specific rule or guidance updates that strike the right balance between oversight and adaptability.

Compensation Arrangements

FINRA draws attention to two particular types of compensation arrangements where existing rules and regulatory frameworks may be ripe for change.

First, compensation arrangements related to personal services entities (PSEs) have recently come under scrutiny. PSEs are legal entities, such as limited liability companies, that are often formed by registered representatives as a vehicle to receive compensation for the representatives’ services, while also achieving tax benefits and other benefits. The problem with this compensation arrangement is that, under existing guidance, receipt of transaction-based compensation traditionally has been a strong indicator of broker-dealer activity. As a result, member firms often have concerns about paying transaction-based compensation directly to PSEs, because of uncertainty as to whether doing so could require the PSE to register as a broker-dealer and/or violate the member firm’s duty to maintain supervisory control over the securities-related compensation paid directly to registered representatives.

Second, there has been a recent rise in programs that pay continuing commissions to retired registered representatives or their beneficiaries. Under existing rules (in particular Rule 2040(b), however, such compensation arrangements are valid only if the registered representative contracts for such continuing commissions before an unexpected life event that renders the representative unable to work.

FINRA is seeking comments on potential regulatory or rulemaking changes that could facilitate these types of compensation arrangements, or ease the regulatory burden associated with them, while still continuing to preserve effective broker-dealer supervision.

Fraud Protection

FINRA is considering changes to existing rules designed to help prevent fraud.

In particular Rule 2165 currently allows firms to place temporary holds on account activity — in the accounts of a “specified adult” — when the firm reasonably believes that financial exploitation of that adult has occurred or is occurring. But these temporary holds are subject to time limits, which can sometimes constrain the firm’s ability to protect customer assets, such as when the firm is unable to convince the customer that financial exploitation is occurring, or when an investigation has not yet concluded. Thus, FINRA is exploring whether to expand the time limits, or to extend the application of Rule 2165 beyond “specified adults.”

FINRA is also seeking comments on ways to potentially modify or enhance Rule 4512, which requires firms to make efforts to identify a “trusted contact person” for all non-institutional accounts — i.e., a person whom the firm can contact when a customer is unavailable or becomes incapacitated.

Leveraging FINRA Systems to Support Member Compliance

Member firms can currently employ FINRA’s systems in a variety of ways to support their compliance efforts, including relying on the CRD system, FINRA’s verification process, the Financial Professional Gateway, and the newly launched Financial Learning Experience to satisfy certain of their regulatory requirements.

As part of the FINRA Forward initiatives, FINRA is seeking feedback on other ways that FINRA can use its systems to reduce costs and burdens on member firms.

FINRA is requesting that all comments be submitted by June 13, 2025, and comments will be posted publicly on FINRA’s website as they are received.

The Founders Sound the Alarm on the President’s Unchecked Power to Terminate Appointees at Will

“[I]f this unlimited power of removal does exist, it may be made, in the hands of a bold and designing man, of high ambition, and feeble principles, an instrument of the worst oppression, and most vindictive vengeance.”

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution (1833)

President Trump has clearly communicated his administration’s belief in presidential supremacy, emphasizing his authority to fire any federal appointee or employee, even those for whom Congress has required “good cause” for discharge. Regarding federal employee whistleblowers, the assertion of these powers wreaked havoc on the laws designed to protect employees who lawfully report waste, fraud, and abuse. President Trump fired both the Special Counsel and a Member of the Merit Systems Protection Board, both of whose jobs were protected under the federal laws that created the positions. More recently, President Trump has threatened to fire the Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, another appointee whose position is protected under law.

By testing the unitary executive theory in the courts, the debate over the limits of the President’s authority to remove executive officers will soon be decided. The final decisions regarding the President’s removal authority will have a lasting impact on all federal employee whistleblowers, as the legal framework designed to protect these whistleblowers was all premised on the independence of the officials making final determinations in retaliation cases. If these officials are not independent (i.e., are not free from the threat of discharge by a sitting President), one of the most important safeguards included in the whistleblower laws covering federal employees will be compromised.

As the debate over Presidential powers moves through the halls of Congress, the Courts, and ultimately by the voters of the United States, the concerns raised by the Founders of the United States need to be carefully considered. The policy issues they identified years ago continue to resonate today.

The first Founder to comment on the President’s authority to remove officials was Alexander Hamilton. While the States were debating whether to approve the Constitution, Alexander Hamilton directly addressed this issue in Federalist No. 77. Hamilton explained that “the consent of [the Senate] would be necessary to displace as well as to appoint.” Hamilton recognized that the U.S. Constitution required a check and balance on the President’s authority to remove all non-judicial appointees who were confirmed by the Senate.

In other words, the issue was not whether or not the President had the constitutional power to fire appointees, but rather whether the Constitution required Senate approval for any such termination. Hamilton understood that, not only was the President’s power to terminate limited, but he went further and stated that any such termination had to be approved by the body that had originally approved the appointment (i.e., the Senate).

In 1803, a pivotal constitutional law issue arose in the landmark case Marbury v. Madison. The decision was authored by the most respected Supreme Court Justice in history, Chief Justice John Marshall. Justice Marshall explained that the President’s power of removal was controlled by Congress. Congress established the terms of the law establishing the office in question. This reasoning was not just accepted; it was a cornerstone of the unanimous decision, grounded in Congress’s authority to create inferior offices and define the rules governing them. The Constitution explicitly designates these powers not to the President, but to Congress.

In discussing the President’s removal authority, Chief Justice Marshall explained: “Where an officer is removable at the will of the executive, the circumstance which completes his appointment is of no concern…but when the officer is not removable at the will of the executive, the appointment is not revocable, and cannot be annulled.” Thus, if Congress creates a position for which the occupant cannot be fired “at will,” and termination from that position must follow the restrictions placed on it by Congress.

Justice Marshall further explained that a President is barred from simply removing officers at his pleasure if Congress did not grant the President such powers: “[Mr. Marbury] was appointed; and [since] the law creating the office gave the officer a right to hold for five years, [he was] independent of the executive, [and] the appointment was not revocable.”

The most authoritative discussion of the policies underlying the power of a President to remove inferior officers was carefully explained by Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story’s widely respected 1833 Commentaries on the Constitution. In his text, he provides a thorough explication of the history and background of the removal authority and its significance within U.S. Constitutional law. Justice Story explained the polices that strongly weighed against expanding Presidential powers to include a unilateral right to fire federal appointees or employees, if Congress set limits on such removals.

In the Commentaries, Justice Story warned of the catastrophic impact of unrestrained presidential removal powers:

“[I]f this unlimited power of removal does exist, it may be made, in the hands of a bold and designing man, of high ambition, and feeble principles, an instrument of the worst oppression, and most vindictive vengeance.

***

“Even in monarchies, while the councils of state are subject to perpetual fluctuations and changes, the ordinary officers of the government are permitted to remain in the silent possession of their offices, undisturbed by the policy or the passions of the favorites of the court. But in a republic, where freedom of opinion and action are guaranteed by the very first principles of the government, if a successful party may first elevate their candidate to office, and then make him the instrument of their resentments, or their mercenary bargains; if men may be made spies upon the actions of their neighbors, to displace them from office; or if fawning sycophants upon the popular leader of the day may gain his patronage, to the exclusion of worthier and abler men, it is most manifest, that elections will be corrupted at their very source; and those, who seek office will have every motive to delude and deceive the people.

***

[S]uch a prerogative in the executive was in its own nature monarchical and arbitrary; and eminently dangerous to the best interests, as well as the liberties, of the country. It would convert all the officers of the country into the mere tools and creatures of the president. A dependence so servile on one individual would deter men of high and honorable minds from engaging in the public service. And if, contrary to expectation, such men should be brought into office, they would be reduced to the necessity of sacrificing every principle of independence to the will of the chief magistrate, or of exposing themselves to the disgrace of being removed from office, and that, too, at a time when it might no longer be in their power to engage in other pursuits.’

Six years later, in ex parte Hennen (1839), the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously upheld the principle that Congress had the authority to limit the removal authority of the President “by law,” for all appointments that were not “fixed by the Constitution.” Crucially, Hennen held that “the execution of the power [of removal] depends upon the authority of law, and not upon the agent who is to administer it.”

Hennen has never been overturned by the Supreme Court.

The 1903 case Shurtleff v. United States followed Hennen. The Court held that Congress had the authority to limit the removal authority of the President whenever it used “clear and explicit language” to impose such a limitation. Shurtleff has not been overruled by the Supreme Court.

That brings us to the landmark case primarily relied upon by those supporting the imperial powers of the President: Myers v. United States. This case has been mischaracterized as promoting a unitary executive. Far from it. The Court’s 6-3 holding –with distinguished justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. and Louis Brandeis among the dissenters– did not diminish or overturn the precedents established by Hennen or Shurtleff.

The issue at hand was not whether Congress could limit the removal authority of the President. Rather, the case decided a radically different issue: Whether the President needed to obtain the approval of the Senate any time he sought to terminate any official who was confirmed by the Senate. The case concerned an older established doctrine that, because a Senate vote was necessary to confirm certain appointments, a Senate vote should also be needed to remove that official.

The limited scope of the case was clarified by James M. Beck, the Solicitor General of the United States, who argued the case on behalf of the President. His statement to the court was clear: “[I]t is not necessary to decide” the issue of a President’s general removal authority. Further in his argument, after being questioned about the scope of the President’s removal authority, Beck explained that “it is not necessary for me to press the argument [against removal restrictions] that far (i.e., beyond the issue of Senate approval of removal decisions).” In essence, the case of Myers centered on an old argument about Senate interference with executive duties. This issue is fundamentally distinct from the debate today, which focuses on legislative regulations on the President’s ability to fire executive officers.

Justice Brandeis, in his dissent, further elaborated the very narrow nature of the issue decided in Meyers: “We need not determine whether the President, acting alone, may remove high political officers.” Brandeis’ dissent, along with those of Justices Holmes and James Clark McReynolds need to be understood in the context of the Founders’ views on executive power as expressed by Alexander Hamilton (Federalist No. 77), Chief Justice Marshall (Marbury v. Madison), and Justice Story (Commentaries on the Constitution). Justice Brandeis’ explanation of past precedent needs to be given its just weight in the debates that are unfolding today: “In no case has this Court determined that the President’s power of removal is beyond control, limitation, or regulation by Congress.”

Supporters of unrestrained presidential power to fire executive officers often reference the congressional debates on the establishment of the Department of Foreign Affairs in 1789 as their primary justification. However, this reliance again overlooks the historical context of the discussions regarding the president’s authority over foreign affairs.

The congressional vote regarding the removal of an executive officer did not address the constitutional question of whether Congress had the authority to impose restrictions on the president’s ability to terminate such officers. Instead, the issue being decided concerned an opposite proposition. The debate was over an amendment that would have stripped the President of the unilateral authority to remove the Secretary of Foreign Affairs. The amendment sought to strip the President of the power to fire the Secretary of Foreign Affairs. The specific clause the amendment sought to strike from the bill was the ability for the secretary “to be removed from the office of the president of the United States.”

The amendment was introduced by Virginia Congressman Alexander White, who had in the prior year participated in the Virginia convention that voted to approve the Constitution. Congressman White was very clear that the purpose of his amendment was not to decide whether or not Congress had the authority to set restrictions on a President’s removal authority. The issue was whether the Constitution prevented the President from having any such authority. Congressman White was simply raising the issue discussed in Federalist No. 77, i.e., whether the authority of the Senate to approve an appointment implied a requirement that the Senate concur in any removal. The issue was not whether the President had imperial powers, but instead was whether the President’s authority to terminate officers should be severely restricted.

Congressman White explained the meaning of his amendment as follows: “As I conceive, the powers of appointing and dismissing to be united in their natures, and a principle that never was called in question in any government, I am adverse to that part of the clause which subjects the secretary of foreign affairs to be removed at the will of the President”.

Although his amendment was not approved, Congressman White’s perspective—that the power of removal should be radically restricted—was supported by many members of the First Congress. But in defeating White’s amendment, the First Congress did not enact any law that would restrict Congress from placing limits on the removal powers of a president. That issue was simply not before the First Congress.

Regardless of the various arguments now being raised concerning the President’s removal authority, the warnings articulated by Justice Story have never been refuted. If the Supreme Court were to conclude that Congress lacked the authority to limit the President’s power to fire, at-will, any and all executive officers, the fear articulated by Justice Story would become the law of the land, and as he warned, would be “eminently dangerous to the best interests, as well as the liberties, of the country”.

Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States, § 1533 (1st ed. 1833).

Compl. Dellinger v. Bessent, No. 1:25-cv-00385 (D.D.C. Feb. 2, 2025) ECF 1, Attachment A.

Tom Jackman, Federal Judge Rules Trump’s Firing of Merit Board chair was illegal, Wash. Post (Mar. 4, 2025), https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2025/03/04/trump-firing-cathy-harris-mspb-illegal/.

Colby Smith & Tony Romm, Trump Lashes Out at Fed Chair for Not Cutting Rates, New York Times, (Apr. 17, 2025), https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/17/business/economy/trump-jerome-powell-fed.html.

The Federalist, No. 77 (Alexander Hamilton).

Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 137 (1803).

See McAllister v. United States, 141 U.S. 174 at 189). (reaffirming the holding of Marbury v. Madison in regard to Presidential Powers 141 U.S. 1704).