Iowa Requires Equal Treatment for Adoptive Parents by Employers

On May 19, 2025, Iowa Governor Kim Reynolds signed House File 248, which requires employers to treat adoptive parents the same as biological parents under certain circumstances. Specifically, if an employee adopts a child up to six years of age, an employer must treat the employee “in the same manner as an employee who is the biological parent of a newborn child for purposes of employment policies, benefits, and protections for the first year of the adoption.”

The law defines adoption as the “permanent placement in this state of a child by the Department of Health and Human Services, by a licensed agency under chapter 238 [child-placing agencies], by an agency that meets the provisions of the interstate compact in section 232.158, or by a person making an independent placement according to the provisions of chapter 600.”

The law does not require employers to provide disability leave to an employee without a qualifying disability under an employer’s disability policies. However, Iowa employers should review any policies or benefits geared toward new parents to ensure compliance with the law.

The law will take effect on July 1, 2025, as Iowa Code § 91A.5B and it will be enforced by the Iowa Department of Inspections Appeals and Licensing.

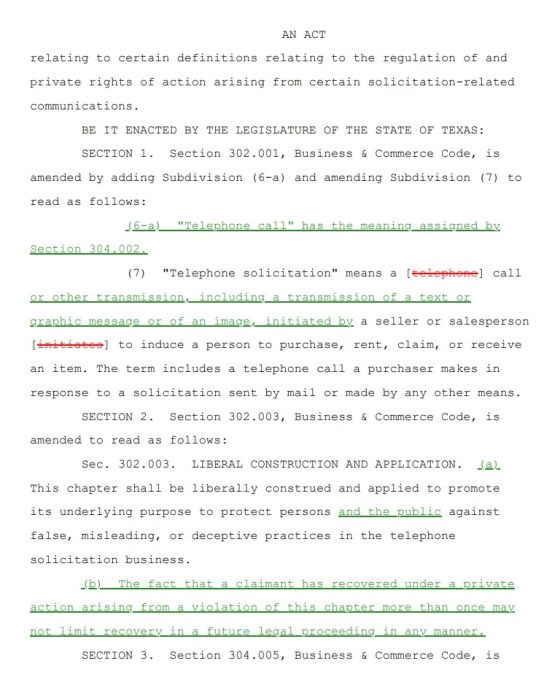

Everything Is Bigger in Texas: SB140 Passed—Texas’ New Mini-TCPA Takes Effect September 1, 2025! Bringing New Private Right of Action, Broader Telephone Solicitation Definition & Right to Repeat Claim

On June 20, 2025 – Governor Abott signed into law Texas Bill SB140 – as TCPAWorld previously reported the Texas-sized bill drastically amends the Texas Mini-TCPA statute – the Texas Business & Commerce Code (“TBCC”) by creating a private right of action under the Deceptive Trade Practices act that provides triple-stacked liability, extends the definition of telephone solicitations to cover text messages, and gives an open door to serial lawsuits.

The new law will take effect on September 1, 2025.

So for those who are making telemarketing calls or text messages in the Lone Star State – here’s what you need to know right now:

Private Right of Action Automatically Afforded Under Deceptive Trade Practices Act (“DTPA”): The new Texas Law creates a NEW private right of action under the DTPA for telemarketing violations – such as noncompliance with call-hour restrictions, failure to register, ignoring opt out requests, and using prohibited automated dialing or announcing devices (“ADAD”). Under the DTPA, consumers can seek treble damages, mental anguish awards and attorney’s fees – substantially increasing the potential exposure for a Texas telemarketing violation. The bill explicitly states that these chapters should be “liberally construed” to protect folks against false, misleading, or deceptive practices in telephone solicitation and telemarketing.

Expanded Definition of “Telephone Call” and “Telephone Solicitation”: A telemarketing call no longer only includes a voice call – it now includes text messages, images, graphics messages, or other electronic transitions initiated by a seller to induce a person to purchase, rent, claim, or receive an item. So the ambiguity in Texas is over – SB140 brings SMS, MMS, or other visual solicitations within the scope of the TBCC.

Private Right of Action for Repeat Claims: The new law clarifies that multiple legal recoveries for the same violation will not limit future recovery. Expect to see even more aggressive, serial litigants and filings in Texas!

You can see the new amendments here:

Now the TBCC is already a hotly litigated statute in Texas and particularly appealing to serial plaintiffs – – especially because of Texas’ registration requirements with a $5,000 per violation penalty. If you are operating in or contacting consumers in Texas, its critical to keep in mind:

Private Right of Action Under TBCC: Currently, under Section 304.052 of the TBCC, consumers do have a private right action for violations of Texas’s DNC and ADAD regulations – however this right is limited by procedural requirements. Before filing a lawsuit, a consumer must file a complaint to either the Texas Public Utility Commission, the Texas Attorney General, or any state agency. If the agency subsequentially initiates its own civil enforcement action in response, the consumer cannot pursue their claim for damages. If the consumer fails to file such a complaint – or cannot prove that the agency declined to act – their privacy action under the TBCC is barred. But with the NEW added private right of action under the DTPA it appears consumers can bypass those procedural barriers and bring claims directly for telemarketing violations – including for DNC violations, ADAD use, and text messages – without having to first go through a state agency. Expect to see a surge in private lawsuits in Texas now permitting treble damages, attorney’s fees and mental anguish claims.

Triple-Stacked Liability? TCPA + Mini-TCPA + DTPA: Texas already allows for what appears to be dual recovery under both the TCPA and TBCC. While real TCPAWorld dwellers understand that double recovery for the same violation under both state and federal law should be impermissible, (See the Czar’s masterful win in Masters v. Wells Fargo, 12-CA-376-SS (W.D. Tex. Jul. 11, 2013), some Texas courts have erroneously held that a violation of the TCPA constitutes an automatic violation of the TBCC. So that means a TCPA violation in Texas can cost you not $500.00 but $1,000.00. Automatically. And every time. And now layer on top potential DTPA damages!

Texas Registration Requirements: Section 302.101 of the TBCC requires sellers to hold a registration certification if making telephone solicitations from Texas or to a purchase in Texas. Violations of this provision will cost you $5,000 a pop – however note the registration requirement does have a bunch of exemptions folks can leverage.

Everything is indeed bigger in Texas.

Texas is supposed to be famously pro-business but these new amendments to its mini-TCPA law massively expands the reach of the statute and opens the door to a rash of new lawsuits against unsuspecting businesses big and small. This is a huge gift to plaintiff’s attorneys who may had the doors to federal courthouses closed on similar claims.

California’s SB 690: A Game-Changer for Website Privacy Lawsuits Pushes Forward

On June 3, 2025, the California Senate unanimously passed Senate Bill 690 (SB 690) in a 35-0 vote, a strong show of support for reining in a flood of lawsuits that have taken many companies by surprise over the last few years. The bill now heads to the California Assembly, where it will face further scrutiny. If ultimately signed into law, SB 690 could reshape how privacy law is enforced in the digital space, offering much-needed clarity (and relief) for businesses across the country.

What is SB 690 All About?

SB 690 is aimed squarely at modernizing how California’s Invasion of Privacy Act (CIPA) is applied in today’s online economy. Originally passed in 1967 to address concerns around wiretapping and old-school eavesdropping, CIPA has recently been used in a very different context against websites and online tools for tracking online users’ behavior and use of a website.

In the last few years, plaintiffs’ lawyers have filed a wave of lawsuits alleging that everyday digital tools, such as cookies, chatbots, and analytics software violate CIPA. Some lawsuits even treat these technologies as illegal surveillance devices under the law. The result? A growing number of businesses, from major retailers to small e-commerce shops, have been hit with expensive and time-consuming legal threats.

Many of these cases are class actions, often pushing businesses to settle rather than fight it out in court. Critics have called this a form of legal “gotcha” using a decades-old law to penalize routine online practices that are otherwise regulated by California’s more recent privacy laws.

What SB 690 Would Change

SB 690 seeks to fix this problem by updating CIPA to reflect how digital communication and data collection actually work today. The bill would:

Exempt businesses from CIPA liability when they record or intercept online communications for a “commercial business purpose.”

Clarify that tools like session replay software, chat logs, or web tracking pixels are not “wiretaps” or surveillance devices when used in standard business operations.

Prevent private lawsuits (i.e., lawsuits brought by consumers, not the government) related to these practices, as long as the company is using the data for a valid business reason.

Importantly, SB 690 defines “commercial business purpose” by borrowing language from California’s existing privacy laws—the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) and California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA). That means businesses following those laws’ rules around data collection, marketing, analytics, and consumer opt-outs would be protected under SB 690.

What About Current Lawsuits?

Originally, SB 690 was written to apply retroactively, which would have wiped out many of the CIPA lawsuits already in progress. But that retroactive provision faced resistance and was removed just before the Senate vote. As it stands now, the bill would only apply to future cases, so businesses already facing CIPA lawsuits won’t receive immediate relief, and websites that track users before obtaining consent (particularly in California) could still face these demands and lawsuits in the meantime.

Why This Matters

Supporters of SB 690 argue that it restores legal balance. California already has some of the toughest privacy laws in the country. The CCPA and CPRA give consumers strong rights, including the ability to opt out of having their data sold or shared. But CIPA, which wasn’t designed for the internet era, has created an overlapping (and often conflicting) patchwork of rules.

The business community has been calling for reform, arguing that the CIPA lawsuits are stifling innovation and creating a “tax” on companies just for using standard tools to understand their customers or secure their platforms.

What’s Next?

SB 690 now moves to the California Assembly, where it will go through committee hearings and floor votes. If it passes the Assembly without changes, it will head to Governor Newsom’s desk. If amended, it may need to go back to the Senate for a final vote.

If SB 690 becomes law, businesses that use standard online tools for legitimate purposes (marketing, security, customer service, etc.) and comply with CCPA/CPRA rules will be far less likely to face CIPA lawsuits. That could mean fewer legal headaches, fewer settlements, and more certainty in how businesses can operate online.

But until the bill is fully enacted, the current legal risks under CIPA remain so businesses should stay alert and ensure compliance with existing privacy laws. The battle over online privacy enforcement in California is far from over, but SB 690 could mark a turning point.

Fair Workweeks: Navigating the Patchwork of Predictive Scheduling Laws

Predictive scheduling laws, also known as “Fair Workweek” laws, are gaining traction across the United States to protect hourly workers from erratic and last-minute shift changes. These laws typically require employers to provide employee work schedules at least two weeks in advance and offer predictability pay when changes are made without sufficient notice. The goal is to provide employees—especially those in retail, food service, and hospitality—greater stability and transparency in their work schedules.

Predictive scheduling laws have been enacted in several jurisdictions across the United States, including cities like Berkeley, Chicago, Emeryville, Los Angeles, New York City, Philadelphia, San Francisco, San Jose, and Seattle. Oregon has also enacted them statewide.

On July 1, 2025, the County of Los Angeles is set to join these jurisdictions. The Los Angeles County ordinance applies to retail employers with over 300 employees worldwide, operating in unincorporated areas of Los Angeles County. Like its counterparts, the Los Angeles County predictive scheduling ordinance contains various requirements, including but not limited to:

Advance Scheduling

Employers must provide employee work schedules at least 14 calendar days in advance.

Employees have the right to decline any changes to the original schedule that would add work hours or additional shifts.

Good Faith Estimate

Employers must provide employees with a written estimate of expected work schedules at hiring and/or within 10 calendar days of an employee’s request.

If the employee’s actual hours, days, location, or shifts worked substantially deviate from the good faith estimate, employers must present a documented legitimate business reason unknown at the time of providing the good faith estimate.

Predictability Pay

Employers must pay employees an additional hour of pay at their regular rate for each work schedule change that does not result in a loss of time or results in more than 15 minutes of additional work time.

Employers must pay employees one-half of their regular rate of pay for time not worked due to employer-initiated schedule changes.

Predictability pay is not required if: (1) an employee requests the schedule change; (2) an employee voluntarily accepts a schedule change due to another employee’s absence; (3) an employee accepts extra hours offered prior to the hiring of new employees or workers; (4) an employee’s hours are reduced due to the employee’s violation of law or of the employer’s policies; (5) the employer’s operations are “compromised pursuant to law”; or (6) extra hours worked require the payment of overtime.

Rest Between Shifts

Employers are required to give employees at least 10 hours of rest between shifts unless the employee provides written consent to work two shifts with fewer than 10 hours of rest in between.

If an employee consents, they are entitled to “a premium of time and a half for each shift not separated by at least ten (10) hours.”

Additional Hours Must Be Offered to Current Employees

Employers must offer available work hours to current employees before hiring new staff.

Employers must offer the additional work hours to each current employee either in writing or by posting an offer at the worksite.

Employers must make the offer at least 72 hours prior to hiring any new staff.

Upon receipt of the offer, existing employees have 48 hours to accept the offer of additional hours in writing.

Upon the expiration of the 48 hours, the employer may hire additional staff members to work any additional hours that current employees do not accept.

At any time during the 72-hour period, if the employer receives written confirmation that none of its current employees will accept the additional work hours, the employer may immediately hire new staff members.

Employer Takeaways

While the Los Angeles County ordinance and its counterparts aim to promote fairness and stability for workers, they may also introduce compliance challenges for employers. This is especially true for the Los Angeles ordinance as the County has yet to release FAQs and/or consolidated regulations to help employers comply with the new law. To that end, predictive scheduling laws across the board tend to be highly technical and nuanced, requiring employers to navigate a web of compliance obligations. The complexity increases for companies operating across multiple jurisdictions, many with their own versions of predictive scheduling rules – making a one-size-fits-all policy difficult to apply.

To that end, businesses must balance operational flexibility with legal obligations. Employers may consider implementing reliable scheduling software to help manage jurisdictional changes and track compliance. Although sophisticated scheduling software may be beneficial, it is crucial for companies and their legal teams to continually assess compliance with these evolving predictive scheduling laws. Accordingly, employers should train managers and human resources professionals on the various predictive scheduling legal requirements and establish clear communication channels for shift changes to help ensure that employees are aware of their rights to decline last-minute modifications. It is also crucial for employers to maintain records of schedules, changes, and communications to comply with these laws’ record-keeping requirements.

The expansion of predictive scheduling laws across jurisdictions presents both challenges and opportunities for employers. While the regulatory landscape is intricate, investing in scheduling systems, training management teams, and fostering open communication with employees can help businesses meet legal requirements as well as enhance workplace morale and operational efficiency.

Bid Protests in Hawaii

The state of Hawaii provides a detailed statutory framework for protesting state procurements to ensure fairness, accountability, and transparency in the government contracting process. This article outlines the essential protest procedures under Hawaii Revised Statutes (HRS) Chapter 103D, including initial protest requirements, administrative hearings, and judicial review.

1. Who May Protest and When?

Under HRS § 103D-701, any actual or prospective bidder, offeror, or contractor who is aggrieved in connection with the solicitation or award of a contract may file a protest. However, the protest must adhere to strict timelines:

General Deadline: Within five working days of when the aggrieved party knew or should have known of the facts.

Award/Proposed Award Protests: Must be submitted within five working days of the award posting (if no request for debriefing was made).

Solicitation Content Protests: Must be filed before the offer due date.

Protests must be in writing and submitted to the chief procurement officer (CPO) or the designated official named in the solicitation.

Protesters are entitled to a stay of the procurement pre-award or a stay of performance post-award.

2. Resolution by the Procurement Officer

Before any formal administrative hearing, the CPO or designee has the authority to resolve protests under HRS § 103D-701(b). If mutual resolution fails, the CPO must issue a written decision that:

States the reasons for the decision;

Notifies the protester of the right to pursue an administrative hearing under HRS § 103D-709.

For construction or airport contracts, this decision must be issued within 75 calendar days, with a possible 45-day extension for good cause.

Pending the CPO’s decision, no further action may be taken on the contract unless the CPO issues a written determination that proceeding is necessary to protect substantial state interests.

3. Relief Available

If a protest is sustained, and the protester should have received the award, the protester is entitled to reasonable actual costs, including bid preparation costs—but not attorneys’ fees.

4. Actions if a Procurement Is Found Unlawful

Before Award:

If prior to award it is determined that a solicitation or proposed award of a contract is in violation of the law, then the solicitation or proposed award must be cancelled or revised to comply with the law.

After Award:

If after an award it is determined that a solicitation or award of a contract is in violation of law, and if the contractor acted in good faith, the contract may be:

Ratified, affirmed, or modified, or

Terminated with compensation for work performed (excluding attorneys’ fees).

If the contractor acted fraudulently or in bad faith:

The contract may be voided, or

Ratified/modified with damages reserved to the state.

5. Administrative Review: Hearings Officers (HRS § 103D-709)

If the protest is denied, the aggrieved party may seek de novo administrative review from hearings officers appointed by the Department of Commerce and Consumer Affairs (DCCA):

Hearings must begin within 21 days of request receipt.

A written decision is required within 45 days.

Only parties to the protest may initiate this review.

The standard of proof is preponderance of the evidence.

Jurisdictional Thresholds:

For contracts under $1 million, the issue under protest must exceed $10,000.

For contracts $1 million or more, the issue under protest must equal at least 10% of the estimated value.

Fees & Bonds:

A protest bond of 1% of the estimated contract value is required.

A non-refundable filing fee is also due:

$200 for contracts ≥ $500,000 but < $1 million. $1,000 for contracts ≥ $1 million. Failure to pay results in dismissal. A frivolous or bad-faith protest may lead to forfeiture of the bond to the general fund. 6. Judicial Review (HRS § 103D-710) Only parties aggrieved by the administrative decision may seek judicial review in the circuit court. Key rules include: Must be filed promptly; the court generally loses jurisdiction if not resolved within 30 days. The review is on the record only, with exceptions for newly discovered, material evidence. The court may affirm, reverse, remand, or modify the decision if there is a legal or procedural defect, or if the decision is arbitrary or clearly erroneous. Conclusion Hawaii’s protest procedures are highly structured, requiring strict adherence to filing deadlines, jurisdictional thresholds, and procedural requirements. Contractors and offerors pursuing or defending against a protest should engage with counsel familiar with the nuances of HRS Chapter 103D and related administrative rules. Understanding this framework ensures that your rights as a bidder or offeror are preserved and effectively asserted throughout the procurement process.

Texas Multifamily Revolution: Governor Abbot Considers Texas Senate Bill That Could Transform Zoning for Mixed-Use Residential / Multifamily Developments

Introduction to Texas Senate Bill SB 840

To combat the housing shortage in Texas, the Texas Senate introduced Bill C.S.S.B. 840 (SB 840 or the bill) in April 2025. The purpose of the bill is to streamline the conversion of non-residential buildings and raw land to mixed-use residential or multifamily use. The Texas Senate and House passed the bill on a bipartisan basis, and it was sent to the Governor’s office on May 28, 2025. If SB 840 is executed by the Governor, or if the Governor fails to take any action by June 22, 2025, SB 840 is set to become effective September 1, 2025.

SB 840 requires municipalities in the state of Texas to allow for mixed-use residential and/or multifamily residential use and development on properties zoned for office, commercial, retail, warehouse or mixed-use. No reclassification of use or change in zoning may be required for a municipality to authorize the conversion of an existing building or the development of raw land for mixed-use residential or multifamily purposes. The permit approval process is also significantly streamlined. To convert an existing building from a nonresidential use to mixed-use residential or multifamily, municipalities may not require a traffic analysis, more than one parking space per dwelling unit, design requirements more restrictive than minimum standards, or impact fees. The bill also provides limitations on municipal enforcement of ordinances related to height, density, parking and setbacks for mixed-use residential or multifamily developments. For example, municipalities may not enforce an ordinance pertaining to mixed-use residential or multifamily that is more restrictive than the greater of (i) the highest residential density allowed in such municipality, or (ii) 36 units per acre.

SB 840 only applies to municipalities with a population greater than 150,000 located in a county with a population greater than 300,000. For reference, Plano, Frisco and McKinney all satisfy the population threshold. The bill does provide exceptions for properties located close to heavy industrial areas and similar uses and does not prohibit municipalities from enforcing regulations related to the preservation of historic districts or landmarks.

This article provides a summary of the components of the proposed bill, while also discussing potential risks and effects for the Texas real estate market. For specific questions regarding the bill’s applicability to certain properties and/or developments, legal counsel should be consulted. The bill is also subject to change.

Summary of the Bill

1. Multifamily Uses Must Be Allowed in Non-Residential Zoning Classifications.

Municipalities must allow mixed-use residential use and development or multifamily residential use and development in a zoning classification that allows for office, commercial, retail, warehouse or mixed-use or development. “Multifamily residential use” is defined as “a site for three or more dwelling units within one or more buildings.” “Mixed-use residential” is defined as “a site consisting of residential and nonresidential uses in which the residential uses are at least 65 % of the total square footage of the development.”

2. Population Minimums.

In its current draft, SB 840 only applies to municipalities with a population greater than 150,000 that are located (wholly or partially) in a county with a population greater than 300,000. For reference, Collin County has a population of over one million, with Plano at approximately 290,000, Frisco at 225,000 and McKinney at 213,000.

3. Streamlined Conversion Process for Office, Retail and Warehouse Buildings.

The proposed changes introduce a streamlined process for converting office, retail and warehouse buildings into residential spaces. A building proposed to be converted to multifamily use must: (i) be used for office, retail or warehouse, (ii) be converted to residential for at least 65% of the building and at least 65% of each floor of the building, and (iii) be constructed at least five years before the proposed date of conversion. However, there are certain requirements that have been waived. In connection with a conversion to mixed-use and/or multifamily use, a municipality may not require: (i) a traffic impact analysis; (ii) construction of improvements or payment of a fee in connection with mitigating traffic effects; (iii) more than one parking space per unit; (iv) the extension, upgrade, replacement or oversizing of a utility facility except as necessary to provide the minimum capacity needed; (v) a design requirement, including a requirement related to the exterior, windows, internal environment of a building or interior space dimensions of an apartment, that is more restrictive than the applicable minimum standard under the International Building Code as adopted as a municipal commercial building code under Section 214.216; or (vi) an impact fee.

4. Streamlined Permit Approval Process.

The bill introduces mandatory permit approvals. If the proposed development and/or change in use meets the land development regulations in SB 840, then the municipal authority responsible for approving building permits must approve the permit and may not require further action for the approval to take effect.

Additionally, the legislation limits the enforcement of building ordinances on mixed-use residential or multifamily developments. A municipality may not adopt or enforce ordinances more restrictive than the following upon mixed-use residential or multifamily residential developments:

Density. Municipality must allow greater of (i) highest residential density allowed, or (ii) 36 units per acre.

Height. Municipality must allow the greater of (i) highest height that would apply to an office, commercial, retail or warehouse development constructed on the site, or (ii) 45 feet.

Setback. Municipality must allow the lesser of (i) a setback that would apply to an office, commercial, retail or warehouse development constructed on the site, or (ii) 25 feet.

Parking. Municipality cannot require (i) more than one parking space per dwelling, or (ii) a multi-level parking structure.

Floor Area/Lot Ratios. Municipality may not enforce an ordinance that restricts the ratio of the total building floor area of a mixed-use residential or multifamily residential development in relation to the lot area of the development.

5. Exceptions to Applicability of SB 840.

The “Heavy Industrial Exception” provides that regardless of population metrics, SB 840 does not apply to (i) zoning classifications that allow heavy industrial uses, (ii) land in close proximity to heavy industrial use, airports or military bases, or (iii) land designated by a municipality as a “clear zone” or “accident potential zone.”

Additionally, SB 840 does not impact municipal ability to enforce:

Short-term rental regulations;

Water quality protection regulations/requirements;

The following regulations, which are generally applicable to other developments in the municipality:

unless otherwise stated: (i) sewer and water access requirements and (ii) building codes;

stormwater mitigation requirements; or

regulations related to historic preservation, including protecting historic landmarks or property in the boundaries of a local historic district.

6. Enforcement of SB 840.

SB 840 authorizes a housing organization or other person adversely affected or aggrieved by a violation of the bill’s provisions to bring an action for declaratory or injunctive relief against a municipality. The court will award court costs and reasonable attorney’s fees to a claimant who prevails in such an action.

Potential Impacts & Associated Risks of SB 840

Likelihood of Passage. There is strong bipartisan support behind SB 840, but various municipalities throughout the state are lobbying against the bill. There may be additional provisions added that provide for exceptions to applicability, or it could be vetoed.

Commercial/Office Risks. The potential upside for commercial/office aside, certain commercial and/or office sites could be negatively impacted by adjected law-quality/high-density multifamily construction.

Multifamily Values. Passage of SB 840 has the potential to devalue existing multifamily properties and/or saturate the multifamily housing market in some municipalities. As multifamily supply increases, developers relying on exclusive and/or isolated multifamily zoning classifications will experience less demand.

Municipal Workarounds. SB 840 provides for exceptions related to the preservation of historic districts for municipalities. If SB 840 passes, there may be a concerted effort by municipalities to categorically and/or geographically broaden historic designations. Municipalities could also conceivably seek to broaden/apply other exceptions – water quality enforcement, heavy industrial, etc.

Infrastructure Risks. Critics of SB 840 have asserted that reclassifications from commercial to multifamily could strain existing utility and roadway infrastructure. They maintain that the bill’s waiver of traffic studies and additional parking mandates presents safety and health risks. The bill’s author (Senator Bryan Hughes) maintains that the population thresholds in the bill, along with the other exceptions to applicability, mitigate these risks.

Single Family Neighborhood Risks. Single family neighborhoods tend to value and/or plan around commercial and/or retail areas. Reclassifying commercial sites to multifamily has the potential to devalue single family homes, which were planned or developed in close proximity to commercial developments.

Administrative/Legal Risk. SB 840 does not directly address Public Improvement Districts or District Overlays, but the present bill would override any conflicting ordinances (subject to the exceptions in the bill). Further localized research would be necessary to assess the interplay between SB 840 and existing overlays for a specific property or district. For example, if a property is reclassified as residential but is located within a traditionally commercial district overlay, there may be a question as to what residential quality standards would apply. Municipalities may need to adopt additional quality controls to ensure that the residential development conforms to the surrounding character if a reclassification occurs.

The proposal of SB 840 represents a legislative effort to combat the Texas housing shortage by facilitating a streamlined conversion of non-residential buildings into mixed-use or multifamily properties. The bill, which has bipartisan support from the Texas legislature, is awaiting action from the Governor. While the bill has obvious upsides for multifamily development, its passage could significantly destabilize the real estate market in Texas by taking away local municipal control.

Blockchain+ Bi-Weekly; Highlights of the Last Two Weeks in Web3 Law: June 20, 2025

It was a busy two weeks in Congress, as key pieces of digital asset legislation move forward in both the House and Senate. While the stablecoin bill in the Senate looks like it may pass quickly, the overarching market structure bill in the House has been hotly debated and appears to lack bipartisan consensus. In other news, various crypto companies are looking to go public after a major stablecoin issuer went public with great success recently, and the SEC is clearing the way for expected upcoming formal rulemaking on the application of securities laws to digital assets.

These developments and a few other brief notes are discussed below.

GENIUS Act Vote in Senate: June 11, 2025

Background: In the Senate, there was a 68-30 vote to invoke cloture on the GENIUS Act, setting the stablecoin bill up for final passage this week. President Trump has put out a statement saying he would sign the bill into law in its current form if it hits his desk. It is expected that by the time of publication of this latest Bi-Weekly update, the GENIUS Act will have passed the Senate, but the bill will still need to go to the House, and then the Senate again if the House makes any changes, before it can reach the President’s desk. The current House stablecoin legislation differs from the GENIUS Act in various ways, including issuers being regulated at both the state and federal levels and how foreign issuers are regulated.

Analysis: The end of week vote to invoke cloture was a move by Senate Majority Leader Thune to end the effort to pass the bill via “regular order” which opens floor proceedings for submission and debate on various amendment proposals. This means the bill is now moving forward with just the changes negotiated with Democrats which lead to 16 Democrats supporting the GENIUS Act in a procedural vote on the Senate floor last month. The list of Senators who voted in favor of cloture is worth monitoring, with Senate Minority Leader Schumer voting against. This stablecoin bill cloture vote came the same week as Treasury Secretary Bessent testified to the Senate Appropriations committee that the Treasury Department is estimating the U.S. Dollar denominated stablecoin market to grow to $2 trillion by the end of 2028.

House Financial Services and Agriculture Committees Markup CLARITY Act : June 10, 2025

Background: The House Financial Services and Agriculture committees held separate hearings to mark up the CLARITY Act with the Financial Services committee focused on the SEC related-elements, while the Agriculture committee worked through the CFTC-related provisions. The biggest change was the protection for crypto developers, wallet makers, and infrastructure providers (previously a separate bill dubbed the Blockchain Regulatory Certainty Act introduced by Representatives Emmer and Torres). The bill passed through the Agriculture committee on an overwhelming 47-6 vote. The vote in the Financial Services committee was a closer 32-19.

Analysis: The Agriculture committee’s overwhelmingly bipartisan vote came right around the start of the Financial Services committee markup, and this fact was harped on regularly by bill proponents as a reflection of bipartisan bill support. The Financial Services markup process was choppier, going well into the night with roughly 40 amendments offered without any expectation of being approved. The current draft would give the CFTC spot market authority over most digital assets, but there is seemingly a push by opponents to give the SEC more power in this area.

House Financial Services Committee Holds Crypto Hearing: June 4, 2025

Background: The House Financial Services Committee held a hearing entitled American Innovation and the Future of Digital Assets: From Blueprint to a Functional Framework to discuss issues related to digital asset regulation. Witnesses included the Chief Legal Officer for Uniswap Labs, Katherine Minarik, and former CFTC Chair Rostin Behnam. Proponents of passing digital asset legislation aimed at encouraging its development in the United States emphasized in the hearing the need for legislative certainty to protect consumers and ensure companies are not leaving the United States to pursue building products and services with blockchain technologies. Opponents cited concerns with the President’s conflicts of interest and argued digital assets should change to meet existing laws rather than making new laws for digital assets.

Analysis: This was just a warmup to the CLARITY Act markup. This hearing started with Ranking Member Waters stating in reference to the CLARITY Act “the only thing clear about this bill is we need to start over.” Republicans pulled a surprise attendance at minority day as well, where typically only the minority party members would attend. The House Agriculture Committee also held a digital asset hearing, but that was less dramatic. There is still much to be done in the regulatory environment, and further changes can be expected including whether what has been dubbed the “DeFi Purity Test” provisions by some is included in whatever the final bill is.

Briefly Noted:

401K Updates: Our last Bi-Weekly update highlighted recent changes from the Department of Labor related to inclusion of crypto in 401(k) plans. Our employment law colleagues here at Polsinelli wrote a larger update on this and how it affects plan managers worth reading here.

Joint Statement on Validator and Developer Protections: The largest advocacy organizations in the digital asset industry put out a joint statement encouraging the Blockchain Regulatory Certainty Act (a bipartisan bill introduced by Representatives Emmer and Torres) be added to the CLARITY Act. It looks like it worked as it was added to the new bill language, so good work all around on this.

SEC Roundtable on DeFi: The SEC roundtable discussion on the agency’s potential role in decentralized finance is worth going back and watching if you did not catch it live. The intro from Chair Atkins was great, as were the additions from Michael Mosier on privacy and data communications systems.

CFTC Chair Nomination Hearing: Brian Quintenz had his confirmation hearing on June 10. It is widely expected he will be confirmed, but the fact that he will likely be the sole CFTC Commissioner shortly after confirmation (if he is confirmed) is an interesting wrinkle.

Samurai Motion to Dismiss: The developers behind bitcoin privacy tool Samourai Wallet moved to dismiss the DOJ’s unlicensed money transmitter related charges last week. “[The DOJ’s legal theory is] akin to charging an encrypted messaging app developer with conspiracy because it may know that some customers use the app to communicate about financial crimes. Or charging a burner phone manufacturer because it may know some customers use the phones to facilitate drug crimes.” DeFi Education Fund and Blockchain Association also wrote an amicus advocating for dismissal (even though the judge took a rare route and denied requests for amicus submissions).

Crypto Company IPOs: Circle’s shares opened at $69.50 on the New York Stock Exchange after its IPO priced at $31. It joins Coinbase as one of the limited publicly traded crypto companies. Gemini has also apparently has confidentially filed for an IPO with the SEC as did digital asset exchange Bullish. There are also expectations for other businesses in the space to explore going public in the near future.

SOL Spot ETF Filings: All the major players filed their S-1 prospectuses with the SEC to try to be in the first batch of SOL ETFs which everybody expects to happen. The big issue remains staking, which these vehicles need to be able to do to be competitive with spot buying on the open market.

SEC Withdraws Rule Proposals: The SEC has formally withdrawn most of the rule proposals issued under the prior administration, including several proposed rules which would have had significant implications on DeFi and crypto custody. It is a rare move to see rule proposals formally retracted rather than fading silently into the background, so this signifies an attempt to create a “clean slate” for upcoming expected rule proposals under Chair Atkins.

Coinbase State of Crypto Report: The Coinbase yearly State of Crypto research is out. Biggest findings are in the cover photo, including that 60% of Fortune 500 executives surveyed said their companies are currently working on blockchain initiatives. They also did a livestream with various big names in crypto and policy going through the results and plans for the upcoming year.

Conclusion:

As the first half of 2025 wraps up, the digital asset policy landscape is entering a critical phase. Stablecoin legislation appears poised for Senate passage, while the broader market structure bill continues to spark heated debate in the House. Meanwhile, key regulatory and enforcement developments—including the SEC’s rule withdrawals, the DOJ’s evolving theories on developer liability, and growing IPO activity—suggest a transitional moment for Web3 in the United States. With bipartisan momentum behind certain reforms and a growing chorus pushing for clarity, the next few months will be essential in shaping the legal infrastructure for blockchain and digital asset innovation.

EU Commission Proposes the Simplification of EU Chemicals Rules for Defence Applications

On 17 June 2025, the European Commission issued a Defence Readiness Omnibus in the form of a Communication accompanied by several legislative proposals (see full list).

The Commission’s proposal aims to speed up defence investments and thereby increase the Member States’ and industry’s capabilities and infrastructures. It notably acknowledges the unfitness of the current regulatory environment of the EU in times of international tensions, including hindrance by environmental legislations.

The package encompasses a proposal accommodating certain requirements of the EU’s chemicals legislation to defence needs by way of amendments to REACH (Regulation (EU) 1907/2006), the CLP (Regulation (EU) 1272/2008 on classification, labelling and packaging) and the BPR (Regulation (EU) 528/2012 on biocidal products).

The proposal foresees the possibility for Member States to exempt certain substances from the requirements of the above cited Regulations “where necessary in the interests of defence”. While such a possibility already exists under all three Regulations, the proposal appears to provide further facilitation, by withdrawing the requirement that the exemption shall only be granted in “specific cases”. This aims to respond to the Member States’ particular caution so far in the use of the exemption.

It further amends the POPs Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2019/1021 on persistent organic pollutants) to ensure that defence readiness be considered in the preparatory stages of substances restriction and prohibition processes.

The package also includes a Commission Notice providing companies with guidance on the application of the sustainable finance framework, the Taxonomy Regulation, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (‘CSRD’) and the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (‘CSDDD’) to the Defence industry.

This new package is issued in a context of intensified calls for simplification by Member States and certain political groups, to which the Commission has already responded via a series of proposals. A broader simplification initiative addressing the requirements of the CLP Regulation is notably expected to be issued on 2 July. Intel suggests that the initiative may be followed by the issuance of a second part later this year.

While this will generate further uncertainties for the industry in the next months, the Commission has shown a strong interest towards input from the industry. Involvement in ongoing discussions with stakeholders is thus key for any industry actor willing to weigh in in the process before the finalization of the proposals this year.

Oregon Law Restricts Common Management Service Organization – Professional Entity Structure

On June 9, 2025, Oregon Governor Tina Kotek signed into law Oregon Senate Bill 951 (Oregon CPOM Law), further expanding Oregon’s prohibition on the corporate practice of medicine (CPOM) doctrine. The stated purpose of the Oregon CPOM Law is to build upon Oregon’s established corporate practice of medicine prohibition, originally established by the Oregon Supreme Court in the 1947 decision in State ex rel. Sisemore v. Standard Optical Co, which banned corporations from holding a majority ownership in medical practices, practicing medicine, or employing physicians.

The Oregon CPOM Law, summarized below, prohibits a variety of practices and arrangements between non-licensed management services organizations (MSOs) and licensed professionals or professional entities that have, until now, been generally permissible. This law is emblematic of the nationwide trend to restrict the influence of non-licensed entities in health care and to restrain private equity-based investment in health care. The Oregon CPOM Law takes a dramatic step toward making Oregon one of the nation’s most stringent CPOM states.

Ownership Restrictions

Under the Oregon CPOM Law, an MSO or any of its shareholders, directors, members, managers, officers, or employees (MSO Agents), subject to the below exceptions, may not:

own or control a majority of the shares in a professional medical entity (Professional Medical Entity) with which the MSO has a management agreement; or

simultaneously serve as a director, officer, employee, or independent contractor of both the Professional Medical Entity and the MSO.

The exceptions permit: (1) an owner of a Professional Medical Entity to serve as an independent contractor of an MSO if the owner owns less than 10% of the Professional Medical Entity, or (2) if the owner’s ownership in the MSO is “incidental” and without relation to the owner’s compensation as a shareholder, director, officer, employee, or independent contractor of the MSO. The Oregon CPOM Law does not define the term “incidental”, and we anticipate that further guidance may be forthcoming on how these exceptions will be interpreted. While we wait for further guidance, an owner of a Professional Medical Entity should proceed with caution prior to receiving equity in an MSO.

These new prohibitions substantially limit the longstanding arrangement in MSO-Professional Medical Entity arrangements where the owner of the Professional Medical Entity holds shares in the MSO, through receipt of rollover equity in the MSO, often while also entering into an independent contractor relationship with the MSO to provide certain services to the MSO. Notably, this prohibition does not apply to out-of-state Professional Medical Entities providing telemedicine in Oregon as long as such entities do not have a physical location in Oregon where patients receive clinical services.

For purposes of the Oregon CPOM Law, “Professional Medical Entity” means entities formed under Oregon law to practice medicine or nursing. The Oregon CPOM Law explicitly excludes from its reach arrangements between MSOs and

Behavioral health care providers;

Licensed opioid treatment programs, providers that primarily provide office-based or medication-assisted treatment services, or providers of withdrawal management services or sobering centers;

Hospitals;

Long-term care facilities;

Residential care facilities; and

PACE organizations, mental health or substance use disorder crisis line providers, or certain Indian health program, Tribal behavioral health or Native Connections program providers.

Additionally, the Oregon CPOM Law does not apply to Professional Medical Entities who through themselves act as an MSO or own a majority interest in an MSO. Notably, the law does not apply to other licensed professions such as psychology, social work, dentistry, and veterinary medicine.

Control Restrictions

In addition to the above, an MSO and its MSO Agents may not: (1) enter into an agreement to control or restrict the sale or transfer of a Professional Medical Entity’s shares or assets, subject to the exceptions below; (2) vote by proxy for a Professional Medical Entity that the MSO manages; (3) cause a Professional Medical Entity to issue shares of stock in an affiliate or subsidiary; (4) pay dividends from an ownership interest in a Professional Medical Entity; or (5) acquire or finance the acquisition of a majority interest in a Professional Medical Entity.

Exceptions to Stock Restriction Agreement Limitation

Under the Oregon CPOM Law, an MSO or its MSO Agents may continue to control or restrict the sale or transfer of a Professional Medical Entity’s equity or assets in the following instances, all of which are generally commonplace in existing MSO- Professional Medical Entity arrangements:

The Professional Medical Entity breaches its management services agreement with the MSO;

The professional license of the Professional Medical Entity’s owner is suspended or revoked;

The owner of the Professional Medical Entity is:

disqualified from holding equity in a Professional Medical Entity;

excluded, debarred, or suspended from a federal health care program, or is under investigation which could result in him or her being, excluded, debarred, or suspended from a federal health care program;

indicted for a felony or another crime that involves fraud or moral turpitude; or

disabled, permanently incapacitated, or dies.

Clinical Decision-Making

The Oregon CPOM Law also prohibits an MSO or its MSO Agents from exercising de facto control over a Professional Medical Entity’s administrative, business, or clinical operations in ways that affect clinical decision-making or the quality of care. “De facto control” includes, but is not limited to, (1) hiring or terminating physicians, nurse practitioners or physician assistants and associates (Licensees); (2) setting work schedules, compensation, or terms of employment for Licensees; (3) specifying the amount of time a Licensee may spend with a patient; (4) establishing billing and collection policies; (5) setting rates for Licensees’ services; and (6) negotiating, executing, performing, enforcing, or terminating the Professional Medical Entity’s payor contracts.

Effective Date

The above restrictions go into effect on January 1, 2026, for (1) MSOs and Professional Medical Entities that are incorporated or organized in Oregon on or after June 9, 2025; and (2) existing MSOs and Professional Medical Entities that are sold or transfer ownership on or after June 9, 2025. For MSOs and Professional Medical Entities that existed before June 9, 2025, and that are not sold or whose ownership is not transferred on or after June 9, 2025, the Oregon CPOM Law goes into effect on January 1, 2029.

Non-Competition and Non-Disparagement

Effective June 9, 2025, the Oregon CPOM Law renders void and unenforceable, with very limited exceptions, (1) noncompetition agreements between MSOs and Licensees, and (2) nondisclosure or non-disparagement agreements between Licensees and MSOs, hospitals, and hospital-affiliated clinics. Noncompetition agreements have traditionally protected MSO investments by preventing Licensees from competing with the Professional Medical Entities with whom the MSO has a management agreement. This prohibition will require significant reexamination of current arrangements between MSOs and Licensees and the structuring of future transactions in this space.

Looking Forward

This move by Oregon to reshape the traditional MSO-Professional Medical Entity model is in line with the continued barrage of state legislation aimed at curbing non-licensed investors’ role in health care, with a particular emphasis on private equity. As we have noted in our previous blog posts, health care transaction review laws are becoming commonplace with states like Massachusetts, California, and Oregon leading the charge. While many of the transaction review laws seek to review and approve proposed transactions involving private equity, this move by Oregon to reshape the traditional MSO-Professional Medical Entity model is a drastic step towards trying to eliminate private equity’s role in the delivery of health care in Oregon generally. Time will tell whether other states will follow Oregon in taking this drastic step and whether any legal challenges will be made to the Oregon CPOM Law.

Shining a Light on Pay: Understanding New Jersey’s New Transparency Mandate for Employers

On June 1, 2025, New Jersey’s Pay and Benefit Transparency Act (“the Act”) took effect, ushering in a new era of openness around pay and benefits for job applicants and employees. This law is part of a growing national movement toward pay transparency, but it introduces several unique requirements and has a broad reach. Employers operating in or hiring employees from New Jersey must act quickly to ensure compliance.

Key provisions of the Act include:

Broad Definition of Employer. The Act applies to any employer that has 10 or more employees over 20 or more calendar weeks and: (a) conducts business in New Jersey; (b) employs individuals within New Jersey; or (c) takes applications for employment within New Jersey even if the employer neither conducts business in New Jersey nor employs individuals in the state. On its face, the Act applies even if a company does not have any active employees in the state of New Jersey. The Act covers private businesses, public entities, and non-profits, as well as job placement and referral agencies and other employment agencies.

Transparent Job Postings. All job postings—whether for a new hire, transfer, or promotion—must now include:

The exact hourly wage or salary, or a defined range (with both a starting and ending point)—vague statements such as “up to $35 per hour” or “$70,000 and above” are not allowed; and

A general description of benefits and other compensation programs for which the employee would be eligible (g., medical insurance, vacation, retirement benefits, parental leave, bonuses, stock, or profit-sharing options). Statements such as “great benefits offered” or “health insurance and more” are not sufficient.

Internal Promotional Notifications. Employers must make “reasonable efforts” to notify all current employees in the “affected department(s)” about promotional opportunities before making a promotion decision. This applies whether the opportunity is advertised internally or externally. A promotion is defined as a change in job title and an increase in compensation. However, there are exceptions for: (a) promotions based solely on seniority or performance, which are exempt from the notification requirement; and (b) promotions made on an emergent basis due to an unforeseen event.

Enforcement and Penalties. The New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development (the “NJDOL”) is responsible for enforcement of the Act. There is no private right of action, and penalties for non-compliance include up to $300 for the first violation and up to $600 for each subsequent violation. Each non-compliant job posting or failure to notify about a promotional opportunity is considered a separate violation, regardless of the number of forums used for the posting. The NJDOL will likely publish administrative regulations further interpreting the Act, but no such guidance is available to date. The lack of various terms leaves some uncertainty as to how the Act will be implemented. For example, the Act does not define an “employee” or “affected department.” Blank Rome will continue to monitor for updates.

Anti-Retaliation Protections. Employers are prohibited from retaliating against employees who discuss or inquire about compensation information.

New Jersey’s Pay and Benefit Transparency Act represents a significant shift in employment practices, with a strong focus on fairness and openness. Taking proactive steps now to update your job postings, promotion processes, and compensation disclosures will help your organization avoid penalties and demonstrate a commitment to workplace equity. Engaging with HR professionals and legal counsel will help your organization implement these new requirements effectively and ensure ongoing compliance with New Jersey’s pay transparency law.

Senate Passes GENIUS Act: Landmark Federal Stablecoin Bill Advances to House

The US Senate has passed the Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for U.S. Stablecoins Act (GENIUS Act) by a vote of 68-30, a significant development for cryptocurrency regulation in the United States. This passage follows the recent advancement of the Digital Asset Market Clarity (CLARITY) Act, a crypto market structure bill, through the House Financial Services and Agriculture committees and toward a full House vote, demonstrating growing bipartisan momentum for comprehensive crypto regulation.[1] The GENIUS Act represents the first comprehensive federal framework governing stablecoins, setting the stage for what could become the most significant digital asset regulatory development in years. The bill now advances to the House of Representatives, with President Trump expressing intent to sign stablecoin legislation before Congress’s August recess.

Key Provisions

The GENIUS Act would create three distinct categories of permitted issuers: subsidiaries of insured depository institutions, federal qualified payment stablecoin issuers regulated by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, and state qualified payment stablecoin issuers supervised by certified state regulators.

The proposed regulatory framework centers on a stringent reserve requirement that would mandate permitted issuers maintain identifiable reserves backing outstanding stablecoins on at least a 1:1 basis. These reserves would need to comprise highly liquid, low-risk assets, including US coins and currency, demand deposits at insured institutions, Treasury securities with 93 days or less maturity, and approved repurchase agreements. The GENIUS Act would explicitly prohibit rehypothecation of these reserves.

The Act would impose comprehensive operational requirements, including monthly reserve composition disclosures, public redemption policies with transparent fee structures, and robust anti-money laundering compliance programs. Large issuers with over $50 billion in outstanding tokens would be required to publish audited financial statements prepared in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles. All permitted issuers would face ongoing examination and supervision by their primary federal regulator, which would be granted enforcement authority, including civil monetary penalties and registration suspension powers.

The legislation would also prohibit stablecoin issuers from paying any form of interest or yield to holders solely in connection with holding stablecoins, effectively barring yield-bearing stablecoins. Additionally, the Act directs Treasury to study “non-payment stablecoins,” including algorithmic stablecoins that rely solely on other digital assets created by the same originator to maintain their fixed price, suggesting these types of stablecoins fall outside the current regulatory framework.

Importantly, the legislation would explicitly exclude payment stablecoins issued by permitted entities from the definition of “security” under federal securities laws, providing critical regulatory clarity that has been a major source of uncertainty in the digital asset space.[2] The legislation would also establish a three-year transition period after which digital asset service providers may only offer stablecoins issued by permitted entities.

Next Steps and Industry Impact

The GENIUS Act must now pass the House of Representatives before reaching President Trump’s desk. Trump has indicated he wants to sign stablecoin legislation before Congress’s August recess, creating potential momentum for House consideration. If enacted, the legislation would take effect 18 months after passage or 120 days after federal regulators issue implementing regulations, whichever comes first.

For the stablecoin sector, the GENIUS Act would provide the regulatory clarity that has long been sought by financial institutions looking to issue or use stablecoins.[3] The framework could accelerate stablecoin adoption by traditional financial institutions while potentially creating competitive advantages for compliant US-based stablecoin issuers over offshore competitors. The legislation’s reserve requirements and operational standards could help establish consumer confidence in stablecoins as a legitimate financial instrument. This may drive growth in the $240 billion market as major corporations explore stablecoin applications.

[1]See Katten’s Quick Reads post discussing the introduction of the Clarity Act here.

[2]See Katten’s Quick Reads post on recent guidance issued by the Division of Corporation Finance of the Securities and Exchange Commission, which clarified that covered stablecoins are not securities.

[3]See Katten’s client advisory on recent guidance from banking regulators easing restrictions against banks and insured depository institutions from participating in “crypto-related activities,” including maintaining stablecoin reserves and issuing cryptocurrencies such as stablecoins.

Update on the SHIPS for America Act

The Shipbuilding and Harbor Infrastructure for Prosperity and Security for America Act (SHIPS for America Act) that was originally introduced in Congress in 2024 has been reintroduced in the Senate of the 119th Congress as S. 1541, with Sens. Mark Kelly, D‑Ariz., Todd Young, R-Ind., Lisa Murkowski, R-Alaska, Tammy Baldwin, D-Wis., Rick Scott, R-Fla., and John Fetterman, D-Pa., as its cosponsors. Sens. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., and Dan Sullivan, R-Alaska, subsequently joined as cosponsors as well. The bill has been initially referred to the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation.

A companion bill of the same name has been introduced as H.R. 3151 in the House of Representatives by Rep. Trent Kelly, R-Miss., on behalf of himself and 37 cosponsors — 21 Republicans and 16 Democrats. The House bill was referred to 12 different committees for consideration within their respective subject matter jurisdictions.

The numerous House committees to which the bill has been referred reflects the comprehensive scope of the bill’s proposals for revitalizing the United States as a maritime nation. While the SHIPS for America Act contains many specific legislative proposals, the principal policy objective of the SHIPS for America Act is to enhance US national security by increasing the involvement of US-built, US-flag vessels in international trade and in particular to compete with China more strategically in that trade. The provisions of the SHIPS for America Act are designed to achieve this overall policy objective in several ways.

First, the SHIPS for America Act contains provisions to establish national oversight and consistent funding for the US maritime industry. If passed, the SHIPS for America Act would create a White House-level position of Maritime Security Advisor, who in turn would lead an interagency Maritime Security Board tasked with making whole-of-government decisions to implement a national maritime strategy.

The SHIPS for America Act would also establish a Maritime Security Trust Fund similar to the dedicated trust funds for other modes of transportation that are supported by user fees, such as the Highway Trust Fund. The purpose of the Maritime Security Trust Fund would be to provide funding for federal programs that support US maritime transportation independent of the annual appropriations process, funded by duties, fees, penalties, taxes, and tariffs collected by US Customs and Border Protection.

To increase the number of US‑built, US-flag vessels engaged in international trade, the SHIPS for America Act would create a new program, the Strategic Commercial Fleet Program, with the goal of establishing a fleet of 250 privately owned US-built, US-flag, US-crewed vessels in international trade by 2030 that are also capable of serving national defense interests. The program would provide annual support payments to cover the difference in capital costs and operating costs associated with constructing and operating a US-built, US-flag vessel as compared with a fair and reasonable estimate of the costs of constructing and operating that type of vessel in a foreign shipyard or under a foreign flag.

The SHIPS for America Act would also establish a shipbuilding financial incentive program that allows the US Maritime Administration (MARAD) to aid in the construction of US-built, US-flag vessels that are not part of the Strategic Commercial Fleet, or to make investments in US shipyards and facilities that produce critical components for shipyards. The SHIPS for America Act would also make changes to MARAD’s Title XI, Capital Reserve Fund, Capital Construction Fund, and Small Shipyards Grants programs designed to encourage the construction of new vessels.

An investment tax credit of 33% would be available for investments to construct, repower, or reconstruct eligible oceangoing vessels in the United States and a 25% investment tax credit for investments in a qualified shipyard in the United States.

The SHIPS for America Act includes several provisions designed to help ensure that there will be cargo for the new vessels to carry. Among them would be an increase in the percentage of US government cargo required to be carried on US-flag vessels from 50% to 100%. Within 15 years, 10% of all cargo imported from the People’s Republic of China would be required to be carried on US-flag vessels. US-built vessels would be required to carry 10% of total seaborne crude oil exports by 2035 and 15% of total seaborne liquefied natural gas exports by 2043.

Finally, the SHIPS for America Act addresses the need for a sufficient shipyard workforce to build these new vessels and for enough mariners to crew them once they are built. Incentives for recruiting and retaining mariners and shipyard workers would include public service loan forgiveness, educational assistance under the GI Bill, and preference when applying for federal employment.

There has been commentary suggesting that some of the different ways in which the SHIPS for America Act seeks to achieve its policy objectives — direct financial support, investment tax credits, cargo preference, and workforce development, among others — could eventually be incorporated into separate bills in order to facilitate their consideration and passage. The projected costs of each of the various incentives will need to be tallied, and funding for them will need to be provided. In any event, the renewed recognition of maritime transportation’s vital role in our nation’s security is likely to provide favorable prospects for the SHIPS for America Act and similar legislative initiatives.