Deference Denied to the South Carolina Department of Revenue

The South Carolina Court of Appeals determined that Duke Energy Corporation (“Duke”) was entitled to claim nearly $25 million in investment tax credits on its 1996 to 2014 South Carolina income tax returns, as the investment tax credit’s five-million-dollar statutory limitation was an annual—not a lifetime—limitation. Duke Energy Corp. v. S.C. Dep’t of Rev., No. 2020-001542 (S.C. Ct. App. Mar. 26, 2025).

The Facts: Duke provides electrical power to millions of customers in the United States, including to residents of South Carolina. To encourage business formation, retention, and expansion, South Carolina provides a tax credit to businesses that invest in certain property in South Carolina, provided specific requirements are met (the “Investment Tax Credit” or the “Credit”).

On its 1996 through 2014 South Carolina corporate income tax returns, Duke claimed a total aggregate Investment Tax Credit of $24,850,727. The South Carolina Department of Revenue (“Department”) audited Duke’s tax returns and disallowed $19,850,727 (approximately 80 percent) of the Credit that Duke claimed. The Department determined that Duke was entitled to claim only five million dollars of Investment Tax Credit—not because Duke did not meet the statutory requirements of the Credit but because the Department believed the statute imposed a five-million-dollar lifetime limitation on the Credit.

Duke protested the Department’s determination, arguing that the five-million-dollar limitation applied on an annual basis. The South Carolina Administrative Law Court (“ALC”) found the statute to be ambiguous and interpreted the Investment Tax Credit’s five-million-dollar limitation to be a lifetime limit. Duke appealed the ALC’s order to the South Carolina Court of Appeals.

The Law: South Carolina’s Investment Tax Credit is available “for any taxable year” in which corporate taxpayers meet the statutory requirements. The statute states, “[t]here is allowed an investment tax credit against the tax imposed pursuant to [the South Carolina Income Tax Act] for any taxable year in which the taxpayer places in service qualified manufacturing and productive equipment property.”

At issue here was the statute’s subsection imposing a five-million-dollar limit amount on the Credit for utility and electric cooperative companies—“[t]he credit allowed by this section for investments made after June 30, 1998, is limited to no more than five million dollars for an entity subject to the [South Carolina] license tax [on utilities and electric cooperatives].”

The Decision: The South Carolina Court of Appeals found that the statute was not ambiguous, reversed the ALC’s order, and held that Duke was entitled to the $19,850,727 of Investment Tax Credits disallowed by the Department.

In making its determination, the Court analyzed the statute as a whole, indicating that while the five- million-dollar limitation subsection does not contain any time-specific language, it refers to the Investment Tax Credit provision that explicitly defines the Credit as being available in “any taxable year.” The Court also looked to the statute’s purpose provision, which indicates that the Credit was designed to “revitalize capital investment in [South Carolina], primarily by encouraging the formation of new businesses and the retention and expansion of existing businesses . . . .” Reading these provisions together, the Court concluded that because taxpayers can claim the Credit each year the statutory requirements are met, and because the Credit’s purpose is not limited to initial business formation, the Legislature intended to encourage continued investment in South Carolina and a lifetime limit of five million dollars does not comply with that intent.

The Court indicated that while it is deferential to the Department’s interpretation of its laws, it could not give deference to an interpretation that conflicts with the Court’s own reading of a statute’s plain language. This is a nice reminder that even in states where courts are deferential to an agency’s statutory interpretation, deference will not always be provided.

Europe: Central Bank of Ireland updates its UCITS Q&A on Portfolio Transparency for ETFs

In a move that will be welcomed by asset managers conducting ETF business in Ireland, or those who are hoping to move into the Irish ETF space, the Central Bank of Ireland has moved to allow for the establishment of semi-transparent ETFs by amending its requirements for portfolio transparency.

Previously, the Central Bank’s UCITS Q&A 1012 provided that the Central Bank would not authorise an ETF unless arrangements were put in place to ensure that information is provided on a daily basis regarding the identities and quantities of portfolio holdings.

The revised Q&A however, while retaining the ability for ETFs to publish holdings on a daily basis, now provides flexibility in that “periodic disclosures” are now permissible, once the following conditions are adhered to:

appropriate information is disclosed on a daily basis to facilitate an effective arbitrage mechanism;

the prospectus discloses the type of information that is provided in point (1);

this information is made available on a non-discriminatory basis to authorised participants (APs) and market makers (MMs);

there are documented procedures to address circumstances where the arbitrage mechanism of the ETF is impaired;

there is a documented procedure for investors to request portfolio information; and

the portfolio holdings as at the end of each calendar quarter are disclosed publicly within 30 business days of the end of the quarter.

These new semi-transparent ETFs will be most attractive for active asset managers who have previously been dissuaded from establishing an ETF in Ireland due to their reluctance to share their proprietary information.

The CFPB Shuts Down Controversial “Regulation Through Guidance” Practices

The acting head of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) continues to winnow out regulatory tools used by agency staff under the prior administration. Just a month after revoking certain interpretative rules and announcing the deprioritized enforcement of others, the CFPB has now reportedly discontinued the Bureau’s longstanding practice of “regulation through guidance.”

An internal agency memorandum circulated last week by Acting Director Russell Vought apparently did not mince words in criticizing the Bureau’s prior use of “guidance” to effectuate backdoor rulemaking: “For too long this agency has engaged in weaponized practices that treat legal restrictions on its authorities [to engage in rulemaking] as barriers to be overcome rather than laws that we are oath-bound to respect. This weaponization occurs with particular force in the context of the Bureau’s use of sub-regulatory ‘guidance.’” Vought’s concern: “[G]uidance materials [have been used] improper[ly] where they impose rights or obligations on private parties outside of the notice-and-comment process prescribed by the Administrative Procedure Act [APA].” That is, to create new regulatory rules, the APA—5 U.S.C. § 553—requires federal agencies like the CFPB to first publish a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking in the Federal Register and to allow the public an opportunity to comment “through submission of written data, views, or arguments.” The prior CFPB regime’s practice of publishing informal “guidance” to impose de facto rules and obligations on covered parties, without prior notice, did not comply with these statutory requirements. Much of the CFPB’s prior guidance left ambiguous their non-binding nature and whether non-compliance would trigger enforcement action by the CFPB. Vought seeks to remedy that concern.

Importantly, the CFPB directive last week seeks more than just a prohibition of future guidance that “purport[s] to create rights or obligations binding on persons or entities outside the Bureau.” The CFPB is also reportedly committed to “rescind[ing] all ‘guidance’ that has unlawfully regulated private parties in the past.” As the agency’s comprehensive internal review concludes in the coming weeks, the CFPB is expected to ultimately renounce significant existing guidance—from advisory opinions to blog posts—that contravene the APA and the Bureau’s constitutional authority for regulatory rulemaking.

Vought’s internal messaging at the CFPB notably occurred on the same day last week that the White House published its own “Memorandum for the Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies.” See Directing the Repeal of Unlawful Regulations, Presidential Memoranda (Apr. 9, 2025). In that Memorandum, the administration instructed agency heads to review and repeal all “facially unlawful regulations” within the next 60 days that do not conform with the recent Loper Bright decision and nine other Supreme Court opinions. With the assistance of its agency heads, including at the CFPB, the executive branch thus continues its path forward to deregulate.

ERISA Fiduciary Duties: Compliance Remains Essential

The Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) establishes a comprehensive framework of fiduciary duties for many involved with employee benefit plans. Failure to comply with these strict fiduciary standards can expose fiduciaries to personal and professional liability and penalties. With ERISA litigation on the rise, a new administration, and recent news that the Department of Labor (DOL) is sharing data with ERISA-plaintiff firms, a refresher on fiduciary duty compliance is necessary.

What Plans Are Covered?

ERISA’s fiduciary requirements apply to all ERISA-covered employee benefit plans. This generally includes all employer-sponsored group benefit plans unless an exemption applies, such as governmental and church plans, as well as plans solely maintained to comply with workers’ compensation, unemployment compensation, or disability insurance laws.

Who Is A Fiduciary?

A fiduciary is any individual or entity that does any of the following:

Exercises authority over the management of a plan or the disposition of assets.

Provides investment advice regarding plan assets for a fee.

Has any discretionary authority in the administration of the plan.

Note that fiduciary status is determined by function, what duties an individual performs or has the right to perform, rather than an individual’s title or how they are described in a service agreement. Fiduciaries include named fiduciaries. Those specified in the plan documents are plan trustees, plan administrators, investment committee members, investment managers, and other persons or entities that fall under the functional definition. When determining whether a third-party administrator is a fiduciary, it is important to identify whether their administrative functions are solely ministerial or directed or whether the administrator has discretionary authority.

What Rules Must Fiduciaries Follow?

Fiduciaries must understand and follow the four main fiduciary duties:

Duty of Loyalty: Known as the exclusive benefit rule, fiduciaries are obligated to discharge their duties solely in the interest of plan participants and beneficiaries. Fiduciaries must act to provide benefits to participants and use plan assets only to pay for benefits and reasonable administrative costs.

Duty of Prudence: A fiduciary must act with the same care, skill, prudence, and diligence that a prudent fiduciary would use in similar circumstances. Even when considering experts’ advice, hiring an investment manager, or working with a service provider, a fiduciary must exercise prudence in their selection, evaluation, and monitoring of those functions and providers. This duty extends to procedural policies and plan investment and asset allocation, including evaluation of risk and return.

Duty of Diversification: Fiduciaries must diversify plan investments to minimize the risk of large losses, with limited exceptions for ESOPs.

Duty to Follow Plan Documents and Applicable Law: Fiduciaries must act in accordance with plan documents and ERISA. Plans must be in writing, and a summary plan description of the key plan terms must be provided to participants.

Fiduciaries also have a duty to avoid causing the plan to engage in any prohibited transactions. Prohibited transactions include most transactions between the plan and individuals and entities with a relationship to the plan. Several exceptions exist, including one that permits ongoing provision of reasonable and necessary services.

Liabilities and Penalties

An individual or entity that breaches fiduciary duties and causes a plan to incur losses may be personally liable for undoing the transaction or making the plan whole. Additional penalties, often at a rate of 20% of the amount involved in the violation, may also apply. While criminal penalties are rare, are possible when violations of ERISA are intentional. Causing the plan to engage in prohibited transactions may also result in excise taxes established by the Internal Revenue Code.

To limit potential liability, plan sponsors and fiduciaries should ensure the appropriate allocation of fiduciary responsibilities, develop adequate plan governance policies, and participate in regular training. Plan sponsors may purchase fiduciary liability insurance to cover liability or losses arising under ERISA. In addition, the DOL has established the Voluntary Fiduciary Correction Program (VFCP), which can provide relief from civil liability and excise taxes if ERISA fiduciaries voluntarily report and correct certain transactions that breach their fiduciary duties. The VFCP program was recently updated with expanded provisions for self-correction of errors, which are addressed in a previous advisory.

AIFMD 2.0 – Draft RTS and Final Guidelines Published on Liquidity Management Tools

On 15 April 2025, the European Securities and Markets Authority (“ESMA”) published draft regulatory technical standards (the “Draft RTS”) and final guidelines (the “Guidelines”) on Liquidity Management Tools (“LMTs”), as required under the revised Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (EU/2024/927) (“AIFMD 2.0”).

Under AIFMD 2.0, ESMA is required to develop:

regulatory technical standards to specify the characteristics of the liquidity management tools set out in Annex V of AIFMD 2.0; and

guidelines on the selection and calibration of liquidity management tools by alternative investment fund managers (“AIFMs”) for liquidity risk management and mitigating financial stability risk.

The Draft RTS and Guidelines have been published following a consultation period by ESMA. The amendments introduced following the consultation are broadly seen as positive developments from ESMA, introducing greater flexibility for alternative investment funds (“AIFs”) in several cases.

Draft RTS

Some of the key provisions set out in the RTS include:

Redemption Gates

Redemption gates must have an activation threshold and apply to all investors. In the Draft RTS, ESMA has introduced flexibility in expressing activation thresholds for redemption gates. For AIFs, thresholds can be expressed in a percentage of the net asset value (“NAV”), in a monetary value (or a combination of both), or in a percentage of liquid assets. In addition, either net or gross redemption orders shall be considered for the determination of the activation threshold.

ESMA has also introduced a new alternative method for the application of redemption gates – redemption orders below or equal to a certain pre-determined redemption amount can be fully executed while orders above this amount are subject to the redemption gate. The purpose of this mechanism is to avoid small redemption orders being affected by larger redemption orders, that drive the amount of orders above the activation threshold.

Side Pockets

ESMA did not include any provisions in the Draft RTS relating to the management of side pockets, as ESMA concluded there was no mandate within the empowerment of the Draft RTS to allow them to do so.

Applicability of LMTs to Share Classes

The previously published version of the Draft RTS included provisions on the application of LMTs to share classes, requiring the same level of LMTs to be applied to all share classes (e.g. when AIFMs extend the notice period of a fund, the same extension of notice period shall apply to all share classes). ESMA has removed these provisions from the Draft RTS.

Use of other LMTs

Recital 25 of the Draft RTS clarifies that additional LMTs not selected in Annex V of AIFMD 2.0 may be used. These may include, for example, “soft closures” that consist of suspending only subscriptions, only repurchases or redemptions of the AIF.

Other Provisions

Other topics covered in the Draft RTS include swing pricing, dual pricing and anti-dilution levies, as well as redemptions in kind.

Guidelines

Some of the key provisions set out in the Guidelines include:

Selection of LMTs

In the selection of the two minimum mandatory LMTs in accordance with AIFMD 2.0 (set out in Annex V of AIFMD 2.0), ESMA states that AIFMs should consider, where appropriate, the merit of selecting at least one quantitative-based LMT (i.e. redemption gates, extension of notice period) and at least one anti-dilution tool (i.e. redemption fees, swing pricing, dual pricing, anti-dilution levies), taking into consideration the investment strategy, redemption policy and liquidity profile of the fund and the market conditions under which the LMT could be activated.

Governance Principles

AIFMs should develop an LMT policy, which should form part of the broader fund liquidity risk management process policy document, and should document the conditions for the selection, activation and calibration of LMTs. AIFMs also should develop an LMT plan, that should be in line with the LMT policy, prior to or immediately after the activation of suspensions of subscriptions, repurchases and redemptions and prior to the activation of a side pocket.

Disclosure to investors

AIFMs should provide disclosures to investors on the selection, activation and calibration of LMTs in the fund documentation, rules or instruments of incorporation, prospectus and/or periodic reports.

Depositaries

Depositaries should set up appropriate verification procedures to check that AIFMs have in place documented procedures for LMTs.

Other Provisions

The Guidelines also include certain other provisions that impose restrictive obligations on the selection, activation and calibration of LMTs (for example, preventing the systematic activation of redemption gates for funds marketed to retail investors).

Next Steps

The European Commission has three months (i.e. until 15 July 2025) to adopt the Draft RTS, although this period can be extended by one month. The European Commission also has the ability to amend the Draft RTS as required.

Once adopted by the European Commission, the Draft RTS will come into force 20 days following publication in the Official Journal of the European Union.

The Guidelines will be applicable from the day after the Draft RTS comes into force, although AIFMs of funds existing before the date of application of the Guidelines will have a 12-month grace period.

Combatting Scams in Australia, Singapore, China and Hong Kong

Key Points:

Singapore’s Shared Responsibility Framework

Comparing scams regulation in Australia, Singapore and the UK

China’s Anti-Telecom and Online Fraud Law

Hong Kong’s Anti-Scam Consumer Protection Charter and Suspicious Account Alert Regime

The increased reliance on digital communication and online banking has created greater potential for digitally-enabled scams. If not appropriately addressed, scam losses may undermine confidence in digital systems, resulting in costs and inefficiencies across industries. In response to increasingly sophisticated scam activities, countries around the world have sought to develop and implement regulatory interventions to mitigate growing financial losses from digital fraud. So far in our scam series, we have explored the regulatory responses in Australia and the UK. In this publication, we take a look at the regulatory environments in Singapore, China and Hong Kong, and consider how they might inform Australia’s industry-specific codes.

SINGAPORE

Shared Responsibility Framework

In December 2024, Singapore’s Shared Responsibility Framework (SRF) came into force. The SRF, which is overseen by the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) and Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA), seeks to preserve confidence in digital payments and banking systems by strengthening accountability of the banking and telecommunications sectors while emphasising individuals’ responsibility for vigilance against scams.

Types of Scams Covered

Unlike reforms in the UK and Australia, the SRF explicitly excludes scams involving authorised payments by the victim to the scammer. Rather, the SRF seeks to address phishing scams with a digital nexus. To fall within the scope of the SRF, the transaction must satisfy the following elements:

The scam must be perpetrated through the impersonation of a legitimate business or government entity;

The scammer (or impersonator) must use a digital messaging platform to obtain the account user’s credentials;

The account user must enter their credentials on a fabricated digital platform; and

The fraudulently obtained credentials must be used to perform transactions that the account user did not authorise.

Duties of Financial Institutions

The SRF imposes a range of obligations on financial institutions (FIs) in order to minimise customers’ exposure to scam losses in the event their account information is compromised. These obligations are detailed in table 1 below.

Table 1

Obligation

Description

12-hour cooling off period

Where an activity is deemed “high-risk”, FIs must impose a 12-hour cooling off period upon activation of a digital security token. During this period, no high-risk activities can be performed.

An activity is deemed to be “high-risk” if it might enable a scammer to quickly transfer a large sum of money to a third party without triggering a customer alert. Examples include:

Addition of new payee to the customer’s account;

Increasing transaction limits;

Disabling transaction notification alerts; and

Changing contact information.

Notifications for activation of digital security tokens

FIs must provide real-time notifications when a digital security token is activated or a high-risk activity occurs. When paired with the cooling off period, this obligation increases the likelihood that unauthorised account access is brought to the attention of the customer before funds can be stolen.

Outgoing transaction alerts

FIs must provide real-time alerts when outgoing transactions are made.

24/7 reporting channels with self-service kill switch

FIs must have in place 24/7 reporting channels which allow for the prompt reporting of unauthorised account access or use. This capability must include a self-service kill-switch enabling customers to block further mobile or online access to their account, thereby preventing further unauthorised transactions.

Duties of Telecommunications Providers

In addition to the obligations imposed on FIs, the SRF creates three duties for telecommunications service providers (TSPs). These duties are set out in table 2 below.

Table 2

Obligation

Description

Connect only with authorised alphanumeric senders

In order to safeguard customers against scams, any organisation wishing to send short message service (SMS) messages using an alphanumeric sender ID (ASID) must be registered and licensed. TSPs must block the sending of SMS messages using ASIDs if the sending organisation is not appropriately registered and licensed.

Block any message sent using an unauthorised ASID

Where the ASID is not registered, the TSP must prevent the message from reaching the intended recipient by blocking the sender.

Implement anti-scam filters

TSPs must implement anti-scam filters which scan each SMS for malicious elements. Where a malicious link is detected, the system must block the SMS to prevent it from reaching the intended recipient.

Responsibility Waterfall

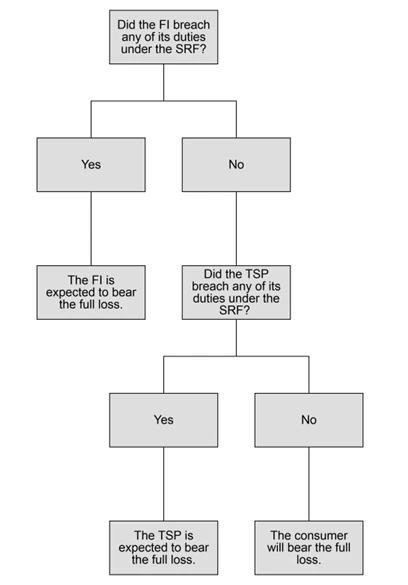

Similar to the UK’s Reimbursement Rules explored in our second article, the SRF provides for the sharing of liability for scam losses. However, unlike the UK model, the SRF will only require an entity to reimburse the victim where there has been a breach of the SRF. The following flowchart outlines how the victim’s loss will be assigned.

HOW DOES THE SRF COMPARE TO THE MODELS IN AUSTRALIA AND THE UK?

Scam Coverage

The type of scams covered by Singapore’s SRF differ significantly to those covered by the Australian and UK models. In Australia and the UK, scams regulation targets situations in which customers have been deceived into authorising the transfer of money out of their account. In contrast, Singapore’s SRF expressly excludes any scam involving the authorised transfer of money. The SRF instead targets phishing scams where the perpetrator obtains personal details in order to gain unauthorised access to the victim’s funds.

Entities Captured

Australia’s Scams Prevention Framework (SPF) covers the widest range of sectors, imposing obligations on entities operating within the banking and telecommunications sectors as well as any digital platform service providers which offer social media, paid search engine advertising or direct messaging services. The explanatory materials note an intention to extend the application of the SPF to new sectors as the scams environment continues to evolve.

In contrast, the UK’s Reimbursement Rules only apply to payment service providers using the faster payments system with the added requirement that the victim or perpetrator’s account be held in the UK. Any account provided by a credit union, municipal bank or national savings bank will be outside the scope of the Reimbursement Rules.

Falling in-between these two models is Singapore’s SRF which applies to FIs and TSPs.

Liability for Losses

Once again, the extent to which financial institutions are held liable for failing to protect customers against scam losses in Singapore lies somewhere between the Australian and UK approaches. Similar to Singapore’s responsibility waterfall, a financial institution in Australia will be held accountable only if the institution has breached its obligations under the SPF. However, unlike the requirement to reimburse victims for losses in Singapore, Australia’s financial institutions will be held accountable through the imposition of administrative penalties. In contrast, the UK’s Reimbursement Rules provide for automatic financial liability for 100% of the customer’s scam losses, up to the maximum reimbursable amount, to be divided equally where two financial institutions are involved.

CHINA

Anti-Telecom and Online Fraud Law of the People’s Republic of China

China’s law on countering Telecommunications Network Fraud (TNF) requires TSPs, Banking FIs and internet service providers (ISPs) to establish internal mechanisms to prevent and control fraud risks. Entities failing to comply with their legal obligations may be fined the equivalent of up to approximately AU$1.05 million. In serious cases, business licences or operational permits may be suspended until an entity can demonstrate it has taken corrective action to ensure future compliance.

Scope

China’s anti-scam regulation defines TNF as the use of telecommunication network technology to take public or private property by fraud through remote and contactless methods. Accordingly, it extends to instances in which funds are transferred without the owner’s authorisation. To fall within the scope of China’s law, the fraud must be carried out in mainland China or externally by a citizen of mainland China, or target individuals in mainland China.

Obligations of Banking FIs

Banking FIs are required to implement risk management measures to prevent accounts being used for TNF. Appropriate policies and procedures may include:

Conducting due diligence on all new clients;

Identifying all beneficial owners of funds:

Requiring frequent verification of identity for high-risk accounts:

Delaying payment clearance for abnormal or suspicious transactions: and

Limiting or suspending operation of flagged accounts.

The People’s Bank of China and the State Council body are responsible for the oversight and management of Banking FIs. The anti-scams law provides for the creation of inter-institutional mechanisms for the sharing of risk information. All Banking FIs are required to provide information on new account openings as well as any indicators of risk identified when conducting initial client due diligence.

Obligations of TSPs and ISPs

TSPs and ISPs are similarly required to implement internal policies and procedures for risk prevention and control in order to prevent TNF. This includes an obligation to implement a true identity registration system for all telephone/internet users. Where a subscriber identity module (SIM) card or internet protocol (IP) address has been linked to fraud, TSPs/ISPs must take action to verify the identity of the owner of the SIM/IP address.

HONG KONG

Hong Kong lacks legislation which specifically deals with scams. However, a range of non-legal strategies have been adopted by the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) in order to address the increasing threat of digital fraud.

Anti-Scam Consumer Protection Charter

The Anti-Scam Consumer Protection Charter (Charter) was developed in collaboration with the Hong Kong Association of Banks. The Charter aims to guard customers against digital fraud such as credit card scams by committing to take protective actions. All 23 of Hong Kong’s card issuing banks are participating institutions.

Under the Charter, participating institutions agree to:

Refrain from sending electronic messages containing embedded hyperlinks. This allows customers to easily identify that any such message is a scam.

Raise public awareness of common digital fraud.

Provide customers with appropriate channels to allow them to make enquiries for the purpose of verifying the authenticity of communications and training frontline staff to provide such support.

More recently, the Anti-Scam Consumer Protection Charter 2.0 was created to extend the commitments to businesses operating in a wider range of industries including:

Retail banking;

Insurance (including insurance broking);

Trustees approved under the Mandatory Provident Fund Scheme; and

Corporations licensed under the Securities and Futures Ordinance.

Suspicious Account Alerts

In cooperation with Hong Kong’s Police Force and the Association of Banks, the HKMA rolled out suspicious account alerts. Under this mechanism, customers have access to Scameter which is a downloadable scam and pitfall search engine. After downloading the Scameter application to their device, customers will receive real-time alerts of the fraud risk of:

Bank accounts prior to making an electronic funds transfer;

Phone numbers based on incoming calls; and

Websites upon launch of the site by the customer.

In addition to receiving real-time alerts, users can also manually search accounts, numbers or websites in order to determine the associated fraud risk.

Scameter is similar to Australia’s Scamwatch, which provides educational resources to assist individuals in protecting themselves against scams. Users can access information about different types of scams and how to avoid falling victim to these. Scamwatch also issues alerts about known scams and provides a platform for users to report scams they have come across.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Domestic responses to the threat of scams appear to differ significantly. Legal approaches explored so far in this series target financial and telecommunications sectors, seeking to influence entities in these industries to adopt proactive measures to prevent, detect and respond to scams. While the UK aims to achieve this by placing the financial burden of scam losses on banks, China and Australia adopt a different approach by imposing penalties on entities failing to comply with their legal obligations. Singapore has opted for a blended approach whereby entities which have failed to comply with the legal obligations under the SRF will be required to reimburse customers who have fallen victim to a scam. However, where the entities involved have met their legal duties, the customer will continue to bear the loss.

Look out for our next article in our scams series.

The authors would like to thank graduate Tamsyn Sharpe for her contribution to this legal insight.

The QPAM Exemption – Key Takeaways for Fund Managers with Benefit Plan Investors

As an asset manager, you may be familiar with the regulatory issues that come into play when a fund permits investments from “benefit plan investors,” which generally include certain employee benefit plans subject to the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974, as amended (“ERISA”) and individual retirement accounts. The main concerns include the need to avoid “prohibited transactions” under ERISA and the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended (the “Code”), and the application of fiduciary status under ERISA when benefit plan investor investments become significant enough so that the fund is deemed to hold ERISA “plan assets.”

Often, managers will work to structure the fund so as to avoid being deemed to hold ERISA plan assets, for example, by limiting benefit plan investor investments to no more than 25% of the fund’s total assets. But what if a sizeable benefit plan investor wants to invest in the fund? How can you track what may and may not be considered a “prohibited transaction” or be confident you’re not inadvertently triggering a breach of your ERISA fiduciary duties? For funds with numerous or sizeable benefit plan investors (generally those exceeding 25% of the fund assets), asset managers may seek relief under the Department of Labor’s Prohibited Transaction Exemption 84-14, as amended, which applies to certain “qualified professional asset managers” or “QPAMs.” This exemption is commonly referred to as the “QPAM Exemption.”

What is the QPAM Exemption?

The QPAM Exemption provides relief from federal excise taxes and required compliance actions that otherwise apply if the fund were to engage in a prohibited transaction under ERISA or the Code.

What transactions are prohibited under ERISA and the Code?

As a general rule, a fiduciary that manages ERISA assets may not use those assets to engage in the sale or exchange, leasing of property, loan or extension of credit, or certain other transactions with a “party in interest” or a “disqualified person.” These transactions are prohibited unless an exception applies. Under ERISA and the Code, the list of “parties in interest” and “disqualified persons” is long and includes service providers to the employee benefit plan (such as the plan’s accountants, attorneys, and brokers with whom the plan conducts business), certain affiliates of the plan, and employee participants and employer sponsors of the plan, among other persons. Many ordinary course transactions are swept into the category of “prohibited transactions.”

What happens if the fund engages in a prohibited transaction?

The IRS imposes a 15% excise tax on the amount involved in any prohibited transaction for each year in which the transaction continues. In addition, any prohibited transaction must be unwound, which can be costly and time-consuming. Engaging in a prohibited transaction is also considered a breach of fiduciary duty under ERISA, which could result in personal liability for plan losses with respect to any individual asset manager with discretionary management authority over the fund’s ERISA plan assets.

Why is it important to qualify as a QPAM?

Asset managers must avoid entering into prohibited transactions when no exemption is available. Due to the sweeping nature of the types of transactions deemed prohibited under ERISA and the Code, managers may find it nearly impossible to enter into many types of transactions on behalf of benefit plan investor clients without first obtaining extensive representations from the investor to ensure the fund won’t inadvertently engage in a prohibited transaction. The QPAM Exemption relieves a manager that qualifies as a QPAM of this administrative burden and operates to avoid the potential for excise taxes and other penalties by excluding many of common transactions that would otherwise be prohibited under ERISA and the Code. In addition, certain lenders transacting with the fund often require the fund to either represent that it does not manage ERISA plan assets or that it qualifies as a QPAM under the QPAM Exemption before moving forward with any loan or credit facility transaction.

Are all prohibited transactions exempt under the QPAM Exemption?

No. Prohibited transactions are generally divided into two categories – party in interest transactions, and fiduciary self-dealing transactions. The QPAM Exemption only applies to the party in interest transactions. Unless another exception applies, a fiduciary managing ERISA plan assets may not engage in certain self-dealing transactions (for example, those involving conflicts of interest between the fund and the benefit plan investor).

Who may qualify as a QPAM?

QPAM status is only available to registered investment advisers (RIAs) and certain types of banks and savings and loan institutions. RIAs seeking QPAM status must generally have total client assets under management and shareholder or partner equity in excess of the thresholds stated in the table below.

Fiscal Year Ending no Later than

AUM Requirement

Equity Ownership Requirement

December 31, 2024

$101,956,000

$1,346,000

December 31, 2027

$118,912,000

$1,694,000

December 31, 2030

$135,868,000

$2,040,000

What else is required to maintain status as a QPAM?

In addition to the qualification requirements, an RIA seeking QPAM status must meet the requirements summarized below.

The RIA must notify the DOL of its intent to rely on the QPAM Exemption, when it changes its name, and again when it no longer qualifies as a QPAM.

The QPAM must acknowledge its fiduciary status in writing.

No single employee benefit plan (including certain affiliate plans) may make up more than 20% of the QPAM’s assets under management.

The party in interest cannot have certain types of authority over the manager.

The QPAM must make an independent decision to enter into the transaction and must have the sole responsibility for the management of plan assets.

The party in interest involved in the transaction cannot be the QPAM or a person related to the QPAM.

The terms of the transaction must be at arm’s length.

The QPAM must maintain records of the transaction for at least six years.

The QPAM and its affiliates must not have engaged in certain disqualifying acts.

We are an RIA seeking to qualify as a QPAM. What’s next?

An investment manager seeking to qualify as a QPAM should first determine whether it currently meets or will meet all of the requirements to satisfy the QPAM Exemption. The qualification points should be fully vetted before notifying the DOL of the intent to qualify and well before making any representations to benefit plan investors or other parties that it may engage in a transaction as a QPAM.

TCPA REVOCATION LESSON: Cenlar’s $714,000.00 TCPA Revocation Settlement Arrives Just In Time to Crystalize Risk

So last Friday the FCC’s new TCPA revocation order went into effect.

While the nastiest parts of the ruling were stayed for one year thanks in large part to the major banks–thanks ABA/MBA and the rest of you!–a good portion of the rule did go into effect.

For those who are not on their revocation game and properly tracking requests the final approval order in a new TCPA class settlement arrives just in time to help you change your ways!

In Kamrava v. Cenlar 2025 WL 1116851 (C.D. Cal April 14, 2025) the court granted final approval to Cenlar’s settlement of a TCPA class involving servicing calls made after revocation of consent.

In many ways this was a throw back case as revocation classes have fallen by the wayside in recent years– leading to less focus on getting it right in some circles. Indeed, the case was filed way back in 2020 and is something of an oddity in today’s TCPAWorld landscape. However, the FCC’s new ruling supercharges risk here, which is why the settlement is so important.

The classes in Kamrava are as follows:

All persons within the United States who received an automated call to their cellular telephone, after revocation of consent, within the TCPA Class Period from defendant or a loan servicer on whose behalf Defendant was sub-servicing, its employees or its agents (the “TCPA Settlement Class”).and

All persons with addresses within the State of California who requested in writing that Defendant or the loan servicer on whose behalf Defendant was sub-servicing to stop contacting them and thereafter (i) received a letter asking them to sign and return a form confirming their cease-and-desist request or (ii) received at least one subsequent telephone call within the RFDCPA Sub-Class Period (the “RFDCPA Settlement Sub-Class”).

I was not involved in the case but I would guess what happened here is Cenlar was only temporarily stopping calls in response to an oral revocation request and then sending out a written letter which, if not returned within a certain timeframe, would result in calls beginning anew.

Thee claims arise between tension between TCPA and FDCPA/RFDCPA revocation rules. Under the debt collection statutes only written requests to stop calls must be honored. But under the TCPA any reasonable means of conveying a revocation is effective– so calls using regulated technology must stop immediately, even if manually launched calls may continue.

Its all part of a thicket of arcane TCPA requirements that can twist an ankle or skin a knee. And in this case Cenlar got snagged for nearly three quarters of a million dollars.

Idaho Joins the De-Banking Ban Wave

Starting July 1, 2025, Idaho will subject financial institutions with total assets over a certain threshold to new restrictions under the Transparency in Financial Services Act. The law follows a growing trend among states seeking to ensure fair access to banking and prevent financial denials based on political, religious, or ideological factors — often known as “de-banking.” Idaho’s statute has much in common with laws passed in Tennessee and Florida (which we covered here) over the past two years.

Covered Institutions and Activities

Like Tennessee (but unlike Florida), Idaho’s statute is crafted to target only larger institutions. Covered financial institutions include:

Banks with over $100 billion in total assets; and

Payment processors, credit card networks, or other payment service providers that processed over $100 billion in transactions in the previous year.

Idaho’s law extends beyond Idaho-chartered institutions, as national banks are specifically covered.

The law applies to any decision involving financial services, which is defined in general terms as “any financial product or service.” This presumably includes the full spectrum of lending, deposits, payments, and other activities offered by the covered institutions.

Prohibited Discrimination Based on “Social Credit Scores”

At the heart of the statute is a prohibition on financial institutions using “social credit scores” to deny or restrict “financial services.” The law defines “social credit scores” broadly, and it includes any analysis or rating that penalizes:

Religious beliefs or practices;

Political expression or associations;

Failure to conduct diversity, equity, or gender-based audits;

Refusal to assist employees in obtaining abortions or gender reassignment services; and/or

Lawful business activities in the fossil fuel or firearms sectors.

The statute allows institutions to apply financial risk-based standards to firearms and fossil fuel businesses, but only if the standards are impartial, quantifiable, and disclosed to customers.

New Explanation Requirement

If a financial institution denies or restricts services, an Idaho customer can request a written explanation. The institution must respond within 14 days and provide:

A detailed basis for the decision;

A copy of the applicable terms of service; and

Specific contract provisions that justify the denial.

Enforcement and Private Rights of Action

Violations of the Transparency in Financial Services Act are treated as violations of Idaho’s Consumer Protection Act. The state attorney general may investigate violations and initiate enforcement actions. But the statute also creates a private right of action: Individuals harmed by violations can sue directly and seek remedies under Idaho’s consumer protection framework.

Preparing for Compliance

Financial institutions covered by the law should begin preparing in advance of the July 1, 2025, effective date. Key steps include:

Evaluating whether service denial or risk assessment practices may encompass any of the prohibited “social credit” criteria.

Familiarizing compliance teams with the law’s requirements to ensure they understand the distinctions between legal risk management and impermissible discrimination.

Assigning personnel to process and respond to customer requests for explanation in a timely fashion.

A National Trend to Watch

Idaho is now the third state to pass a fair access to banking law, and it may not be the last. Financial institutions should give careful thought to their policies and models insofar as they touch on the hot-button activities and issues that animate the de-banking debate.

HM Treasury and FCA Proposals to Reform Regulation of UK AIFMs

On 7 April 2025, HM Treasury (HMT) published a consultation (Consultation) on the reform of the UK regulatory regime for alternative investment funds (AIFs) and their managers, alternative investment fund managers (AIFMs[CM1] ), and the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) simultaneously published a call for input (Call for Input) on how to create a more proportionate, streamlined and simplified regime (the Call for Input and the Consultation together, the Proposals). The Proposals follow the UK’s implementation of the EU Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (UK AIFMD) in 2013 and the UK’s withdrawal from the European Union (Brexit) in 2020.

The Proposals aim to simplify the regulations relating to AIFMs and streamline the existing framework with the intention to make the UK more “attractive” for investment and to encourage growth within the UK economy.

The Current AIFM Regime

The current AIFM regime derives principally from the EU Alternative Investment Managers Directive (EU AIFMD). The application of this regime and the accompanying rules depend on whether an AIFM’s assets under management (AUM) exceed certain thresholds.

In the Consultation, HMT explains that these thresholds have not been updated or reviewed since the introduction of the EU AIFMD in 2013. HMT also describes the current regime creating a “cliff edge effect” where sudden market movements or changes in AUM valuations have inadvertently brought smaller AIFMs within the full scope of the AIFM regime, subjecting such firms to sudden and substantial compliance burdens which it believes has the potential to discourage growth.

HMT Consultation

As a result of the “cliff edge effect”, the Consultation proposes to remove the thresholds and allow the FCA to determine proportionate and tailored rules.

Additionally, HMT proposes two “sub-threshold” categories of “small registered AIFM” that are yet to be authorised:

unauthorised property collective investment schemes; and

internally managed investment companies.

In particular, the Consultation discusses the following key items:

relocating definitions of “managing an AIF”, “AIF”, and “Collective Investment Undertaking” to the Regulated Activities Order, with no change to the regulatory scope;

confirming that there are no plans to amend the UK National Private Placement Regime;

potentially removing the FCA notification requirements when certain AIFMs acquire control of unlisted companies;

prudential rules for AIFMs;

at this stage, there are no proposals to change the rules applying to depositaries, but the FCA is calling for further evidence on whether any changes could be warranted;

reviewing the requirement for appointing external valuers; and

regulatory reporting under AIFMD.

Call for Input

Three New AIFM Thresholds

In the Call for Input, the FCA proposes new categorisations for AIFMs relating to their AIFs’ aggregate net asset value (NAV) (rather than the AUM) of their funds. This metric should be friendlier for managers on the basis that the NAV takes also into consideration the firm’s liabilities and is closer to the “actual value” of the firm, instead of purely considering the value of all assets of the firm.

The Call for Input proposes three divisions and the ability to opt-up to a higher category:

1. Small firms (NAV of £100m or less)

This category of firms would be subject to essential requirements to ensure consumer protection and will “reflect a minimum standard appropriate to a firm entrusted with managing a fund.”

2. Mid-sized firms (NAV more than £100m but less than £5bn)

This category of firms would have a comprehensive regulatory regime that is consistent with the rules that apply to the largest firms, but with fewer procedural requirements. This should, it is hoped, result in the regime for mid-sized firms being more flexible and less onerous than for the largest firms.

3. The largest firms (NAV of £5bn or more)

This category of firms would be subject to rules that are similar to the current full scope UK AIFM regime but tailoring the rules to specific types of activities and strategies. The FCA also intends to simplify AIFMs’ disclosure and reporting requirements.

Other Key Points

Additionally, the Call for Input also considers the following points:

new rule structure for UK AIFMs managing unauthorised AIFs; and

tailoring the rules to UK AIFMs based on the activities they undertake – for example, differentiating between venture capital firms, private equity firms, hedge funds and investment trusts – and their category.

What This Could Mean for UK Asset Management

Driving economic growth is a fundamental point of the current Labour government’s agenda and can be seen through the Proposals. This is also one of, if not the, first time that the UK government and HMT have taken advantage of and embraced Brexit to deviate from the retained EU regulations in an effort to strengthen London as a finance hub.

While the rules relating to Undertakings for the Collective Investment in Transferable Securities (i.e., EU and UK mutual funds, known as UCITS) are unaffected by the Proposals, the Proposals suggest a significant rethink of the UK asset management framework. The Proposals could reduce the regulatory burden on many UK AIFMs, which should be a great benefit to the UK asset management industry post-Brexit. The Proposals therefore focus on emerging and smaller AIFMs in a bid to provide an environment where such firms can continue to grow, without restrictive administrative and regulatory burden.

We expect that this regulatory shift will be welcomed by the market as it has been a complaint for a long time that the current UK AIFMD regime has had too broad of an approach to apply to differing business models.

The Call for Input and the Consultation close on 9 June 2025. The FCA intends to consult on detailed rules in the first half of 2026, subject to feedback and to decisions by HMT on the future regime, while HMT intends to publish a draft statutory instrument for feedback, depending on the outcome of the Consultation.

The Call for Input and the Consultation are available here and here, respectively.

Leander Rodricks, trainee in the Financial Markets and Funds practice, contributed to this advisory.

Ten Minute Interview: Bridging M&A Valuation Gaps with Earnouts and Rollovers [VIDEO]

Brian Lucareli, director of Foley Private Client Services (PCS) and co-chair of the Family Offices group, sits down with Arthur Vorbrodt, senior counsel and member of Foley’s Transactions group, for a 10-minute interview to discuss bridging M&A valuation gaps with earnouts and rollovers. During this session, Arthur explained the pros and cons of utilizing rollover equity, earnout payments, and/or a combination thereof, and discussed how a family office may utilize these contingent consideration mechanics, as tools to bridge M&A transaction valuation gaps with sellers.

The More You Know Can Hurt You: Court Rules Financial Institutions Need ‘Actual Knowledge’ of Mismatches for ACH Scam Liability

On March 26, the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit issued a decision that has important ramifications for banks and credit unions that process millions of Automated Clearing House (ACH) and Electronic Funds Transfer (EFT) transactions daily, some of which are fraudulent or “phishing scams.” In Studco Buildings Systems US, LLC v. 1st Advantage Federal Credit Union, No. 23-1148, 2025 WL 907858 (4th Cir. amended Apr. 2, 2025), the Fourth Circuit held that financial institutions typically have no duty to investigate name and account number mismatches — commonly referred to as “misdescription of beneficiary.” Instead, they can rely strictly on the account number identified before disbursing the funds received. The financial institution will only face potential liability for the fraudulent transfer if it has “actual knowledge” that the name and the account number do not match the account into which funds are to be deposited.

A Phishing Scam Results in Misdirected Electronic Transfers

A metal fabricator (Studco) was the victim of a phishing scam in which hackers penetrated its email systems. Once inside, the scammers impersonated Studco’s metal supplier (Olympic Steel, Inc.) and sent an email with new ACH/EFT payment instructions purporting to be those of Olympic Steel. The instructions designated Olympic’s “new account” at 1st Advantage Credit Union for all future invoice payments. The new account number, however, had no association with Olympic and was controlled by scammers in Africa.

Studco failed to recognize certain red flags in the payment instructions and sent four payments totaling over $550,000. Studco sued 1st Advantage for reimbursement, alleging the credit union negligently “fail[ed] to discover that the scammers had misdescribed the account into which the ACH funds were to be deposited.” Studco claimed that 1st Advantage was liable under Virginia’s version of UCC § 4A-207 because it completed the transfer of funds to “an account for which the name did not match the account number.” Following a bench trial, the district court entered judgment in Studco’s favor for $558,868.71, plus attorneys’ fees and costs. It found that 1st Advantage “failed to act ‘in a commercially reasonable manner or exercise ordinary care'” in posting the transfers to the account in question.

UCC § 4A-207 and Financial Institution Duties and Liability

1st Advantage appealed, and the Fourth Circuit reversed. The Court began by noting that Studco itself failed to spot warning signs in the imposter’s emails: the domain did not match Olympic’s email domain; the new account was at a credit union in Virginia, not Ohio (where Olympic was based); and there were multiple grammatical and “non-sensical” errors contained in the imposter’s instructions.

The Court then turned to 1st Advantage and whether it had a duty to act on any mismatch between the name on the payment instructions (Olympic) and the account number (a credit union customer with no obvious association to Olympic). It first noted the absence of actual knowledge by the credit union. 1st Advantage used a system known as DataSafe that monitored ACH transfers. The Court observed that the “DataSafe system generated hundreds to thousands of warnings related to mismatched names on a daily basis, but the system did not notify anyone when a warning was generated, nor did 1st Advantage review the reports as a matter of course.” The Court further noted that the DataSafe system generated a “warning of the mismatch: ‘Tape name does not contain file last name TAYLOR'” which was the name of the credit union’s account holder, not Olympic.

The Court then assessed Virginia’s version of § 4A-207(b)(1), Va. Code Ann. § 8.4A-207(b)(1), which says in relevant part: “‘If a payment order received by the beneficiary’s bank identifies the beneficiary both by name and by an identifying or bank account number and the name and number identify different persons’ and if ‘the beneficiary’s bank does not know that the name and number refer to different persons,’ the beneficiary’s bank ‘may rely on the number as the proper identification of the beneficiary of the order.'” The Court further noted that the provision states that “[t]he beneficiary’s bank need not determine whether the name and number refer to the same person.” Based upon this, the Court concluded that it “protects the beneficiary’s bank from any liability when it deposits funds into the account for which a number was provided in the payment order, even if the name does not match, so long as it “does not know that the name and number refer to different persons.” [Emphasis added.] Studco argued that constructive knowledge was sufficient or could be imputed to 1st Advantage. The Court disagreed, concluding that “knowledge means actual knowledge, not imputed knowledge or constructive knowledge” and that a “beneficiary’s bank has ‘no duty to determine whether there is a conflict’ between the account number and the name of the beneficiary, and the bank ‘may rely on the number as the proper identification of the beneficiary.'”

In the concurring opinion, however, one judge disagreed that there was no evidence of actual knowledge because 1st Advantage may have received actual knowledge of the misdescription when an investigation of a Federal Office of Foreign Asset Control (OFAC) alert led to a review of the transfers at issue. Because the first two (of four) overseas transfers from the infiltrated 1st Advantage account triggered an OFAC alert, 1st Advantage opened an ongoing investigation into the wires, including a review of the member’s account history. Thus, the concurrence noted that a “factfinder could infer that [the officer’s] investigation led to a [credit union] employee obtaining actual knowledge of a misdescription between account name and number prior to Studco’s two November deposits.”

Lessons Learned Post-Studco

In the age of ubiquitous cyber and other sophisticated scams running throughout the US financial system, the financial services industry surely welcomes this Fourth Circuit decision. The trial court in Studco ruled that 1st Advantage was liable for scam-related ACH transfers in excess of a half-million dollars because 1st Advantage’s core system had triggered a warning regarding the name and account discrepancy, which 1st Advantage did not review or investigate. The fact that 1st Advantage did not undertake to review warnings from its core system appears to have saved 1st Advantage as the Court concluded that “actual knowledge” of the discrepancy was a prerequisite to liability. There was no proof of actual knowledge in this case.

On April 9, 2025, Studco petitioned the Fourth Circuit for rehearing, and alternatively, rehearing en banc with the full court. Studco argues that the panel erred in holding that there was no actual knowledge, pointing out that “1st Advantage opened the scammer’s account and reviewed the account at least 33 times over an approximate 40-day period – each time related to the scammers conducting a suspicious transaction.” Studco argues that a full en banc hearing should be permitted because the application of “UCC Article 4A-207 presents a question of exceptional importance.”

In the end, Studco stands as a warning to banks and credit unions alike that the more they know about the name mismatch issue for any particular transaction, the more liability they may take on. Banks and credit unions should consult their bank counsel to discuss their ACH and EFT review processes and ensure that their processes do not tip into “actual knowledge” and potential liability for transfers rooted in fraud.