Driving Towards the Legalisation of Fully Autonomous Vehicles in the UK

As many will know, the Autonomous Vehicle Act 2024 (the “AV Act”) paved the way to legalising the use of autonomous vehicles on UK roads. However, before any autonomous vehicles can be used on the UK roads (other than under controlled trials), it is important to be aware that the AV Act does not, at this stage, authorise those vehicles for use on the UK’s roads. Rather, the AV Act grants the Secretary of State the power to authorise this at a later date once the “safety principles” for such usage have been determined.

On 10 June 2025, the Secretary of State launched a call for evidence and consultation on the secondary legislation which will be required to establish these “safety principles”:

Call for Evidence on Automated Vehicles: Statement of Safety Principles

The AV Act requires the Secretary of State to prepare a Statement of Safety Principles which is to be used in different ways across the safety framework for automated vehicles including for:

pre-deployment authorisation checks;

carrying out in-use monitoring and regulatory compliance checks; and

undertaking annual assessment on the overall performance of automated vehicles.

This call for evidence seeks information to support an understanding of:

what safety principles might be used;

the safety standards which might be described; and

how safety performance can be measured.

There are also questions about the development of safety principles and how those could be used in practice.

See the “full list of questions” section of the call for evidence for all questions: Automated vehicles: statement of safety principles – GOV.UK

Consultation on Automated Vehicles: Protecting Marketing Terms

The AV Act also gives the Secretary of State the power to protect certain terms, so that they can only be used to market vehicles which have been authorised under the AV Act as being automated (self-driving). In turn, the AV Act then provides that these protected terms must not be used to market driver assistance systems.

This consultation seeks views on this including whether certain terms including “self-driving”, “driverless” and “automated driving” should be protected, whether any symbols should be protected and whether restrictions should only apply only when used to describe a vehicle as a whole.

See section 4 of the consultation for the full list of questions: Automated vehicles: protecting marketing terms – GOV.UK.

Deadline

The deadline for responding to both the call for evidence and consultation (there is no requirement to respond to both though) is 23:59 on 1 September 2025.

The Draft Clean Air Act: Thailand Readies Legislation to Combat Air Pollution

Thailand is suffering from a continuing increase in harmful particulate matter dust (especially PM2.5) and other air pollution in many parts of the country, including Bangkok, its capital and commercial center. There are various causes behind the increase in toxic air pollution, including intense agricultural demands, industrial emissions, urban activities, transboundary pollution, and seasonal factors.

According to several statistics, Thailand is one of the world’s top commercial agricultural producers, with various cash crops, like rice, maize, and sugarcane, grown throughout the country. However, this high level of agricultural production leads to adverse effects on human health, our climate, and the environment.

In Thailand, agricultural burning, using fire to clear land for planting and to remove excess biomass, is a traditional practice that farmers in various parts of the country use for its speed and low-costs. This practice has intensified over the past decades as Thailand transitioned from subsistence farming to commercial agriculture, and Thai farmers came under pressure to satisfy the increasing demands of large agricultural businesses to produce more cash crops. To further exacerbate the issue, Thailand’s neighbors also practice agricultural burning, which can lead to transboundary pollution.

As air pollution gains more attention, especially in developing countries, the United Nations General Assembly (the “UNGA”) passed a resolution in 2022 recognizing the right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment as a basic human right. The UNGA called upon its member states (which include Thailand), international organizations, businesses, and other stakeholders to “scale up their efforts” to ensure a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment for all humans across the world.

To combat air pollution, the authorities in Thailand have enacted a patchwork of legal measures, including stricter vehicle emission standards, promotion of electric vehicles, regulation of industrial emissions, and various other regulatory instruments, to combat practices that result in air pollution. However, at this moment, Thailand does not have any specific and comprehensive legislation to combat the causes of air pollution.

Thus as part of its efforts to combat air pollution in the country and further afield, the Thai government has recently initiated steps to implement a citizen-driven legislative tool designed to serve as the cornerstone of the legal framework for addressing air pollution – the Draft Clean Air Act (the “Draft Act”).

Current Status of the Draft Act

At present, the Thai government is in the stage of reviewing and consolidating the seven versions of the Draft Act, including one proposed by the Cabinet, five submitted by various Thai political parties[1], and one developed by a civil society organization, the Thailand Clean Air Network. These seven versions are being formalized and unified into a single consolidated act.

Specifically, the Draft Act is currently being considered by an Ad Hoc parliamentary committee, which includes senators and is supported by two subcommittees: one focusing on the Draft Act’s principles and administrative structure, and the other on legal liabilities and enforcement.

As part of this legislative process, from 2024 to the present, the committee and its two subcommittees have held numerous meetings to amend and refine the content of the draft.

Once their review is complete, a public consultation will be conducted through the Parliament’s official website. The finalized draft will then be submitted to the House of Representatives for a vote in the remaining readings. If approved, the Draft Act is expected to be submitted for royal assent and officially enacted into law within the next year.

Core Principles and Key Provisions of the Draft Act

Definition of Clean Air

Within the Draft Act, “clean air” is defined as air that is free from pollutants exceeding acceptable standards. These standards will be based on decisions by a national committee, international organizations, or academic consensus, depending on which of the seven versions of the Draft Clean Air Act will ultimately be adopted.

Public Rights to Clean Air

The Draft Clean Air Act recognizes various fundamental rights of the public, including:

Right to breathe clean air

Right to access and receive information

Right to participate in policy and planning

Right to seek environmental justice through the court

Right to health screening and medical treatment

Duties of Persons

The Draft Clean Air Act outlines personal duties on individuals and businesses:

Duty to avoid causing air pollution that adversely affects others

Duty to support and cooperate with government efforts to address air pollution

Problem-Solving Mechanisms

The Draft Clean Air Act proposes the following proactive and preventive mechanisms, to be implemented by the Pollution Control Department, to address air pollution issues:

Monitoring, forecasting, and early-warning systems

Provincial-level pollution databases and mapping

Designation of pollution surveillance or hazardous zones

Measures to tackle transboundary pollution

Economic and Behavioral Incentives

The Draft Clean Air Act proposes several policy, fiscal, and regulatory tools to encourage cleaner practices, including:

Taxes for emitting air pollutants

Air pollution management fees

Deposit-refund system

Allocation and transfer of air pollution emission rights

Risk insurance

Subsidies, support, or incentives for individuals or activities that promote clean air

Other tools or measures as prescribed by the Clean Air Policy Committee

Establishment of a Clean Air and Health Fund

The Draft Act proposes to establish a revolving Clean Air and Health fund intends to support activities to promote clean air, compensate victims of air pollution, and penalize violators, such as:

Relief and compensation for damage caused by pollution

Research and community capacity building

Regional and international collaboration

Litigation and legal enforcement (as further discussed below)

Penalties for Activities Resulting in Air Pollution

It is noteworthy that the various versions of the Draft Act intend to introduce new and robust enforcement structures to combat air pollution.

Firstly, they introduce the concept of Clean Air Officers, empowered in four versions (the ones proposed by the Government, Palang Pracharath, Bhumjaithai, and Pheu Thai). These officers will be able to inspect facilities, demand data disclosures, and, in some cases, suspend operations that are contributing to air pollution.

Secondly, these versions also propose enhanced monitoring systems, data collection at provincial and district levels, and public access to real-time air quality data (as emphasized in Kao Klai’s version). Businesses can expect mandatory environmental assessments and continuous monitoring, particularly in pollution-heavy sectors, like agriculture.

Lastly, the penalties vary across the different versions. For example:

Most of the versions recognize the penalties for polluting activities outside the country; this extraterritoriality concept will be discussed further in parallel with Singaporean law to predict the possible impacts on businesses.

Regarding the matter of imprisonment, the Government’s and Palang Pracharath’s versions impose up to one year of imprisonment in addition to fines of 100,000 Thai Baht for domestic violations, with harsher penalties for cross-border pollution, while the Kao Klai and the Clean Air Network versions propose prison terms of up to five years.

Distinctively, Kao Klai uniquely mandates public disclosure of polluters and environmental transparency for publicly-listed companies, raising ESG and reputational stakes for large corporations.

Several acts impose penalties on companies for failing to report emissions, missing required fees, obstructing enforcement, causing transboundary haze issues, and on officers for neglecting their duties.

Comparative Overview

While Thailand is still in the process of developing its regulatory framework to address air pollution, numerous other countries around the world have already established comprehensive laws and regulations aimed at promoting air quality and reducing pollution.

These international efforts can serve as valuable examples and benchmarks for Thailand as it works towards implementing its own clean air framework. Countries such as the United States, European Union member states, the United Kingdom, the Philippines, and Singapore have enacted robust legislation that sets stringent air quality standards, regulates emissions from various sources, and imposes penalties for non-compliance. These laws not only aim to protect public health and the environment but also encourage sustainable practices and technological innovations to reduce air pollution and its impact on the public and the environment.

United States: The Clean Air Act in the United States is one of the most comprehensive air quality laws globally. It was established in 1963 and significantly amended in 1970, granting the Environmental Protection Agency broad powers to regulate air pollutants throughout the country.

European Union: The EU Air Quality Directive, specifically the revised Ambient Air Quality Directive, sets binding air quality standards for European Union member states. It focuses on pollutants such as particulate matter (PM10 and PM2.5), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), and ozone (O3).

United Kingdom: The United Kingdom has various legislative instruments to combat air pollution, including the UK Clean Air Act 1956, later extended by the Clean Air Act 1968 and consolidated in the Clean Air Act 1993. Most recently, the UK adopted the Environment Act 2021 to further strengthen the UK’s provisions for air quality.

The Philippines: The Philippine Clean Air Act 1999 (Republic Act No. 8749), which establishes a comprehensive air pollution control policy aimed at protecting public health and the environment, imposes strict penalties for environmental violations.

Singapore: Singapore first adopted a legislative instrument to combat air pollution in 1971, the Clean Air Act of 1971. Furthermore, Singapore introduced the Transboundary Haze Pollution Act 2014 (“THPA”), which extends to any conduct or thing outside Singapore that causes or contributes to any haze pollution in Singapore.

Thailand’s attempt to introduce legislation tackling air pollution mirrors a broader regional shift toward imposing cross-border environmental accountability on businesses. It draws clear parallels with Singapore’s THPA, which holds companies liable for haze originating beyond its borders. For instance, in 2013, severe haze from fires located in Indonesia caused hazardous, transboundary pollution in Singapore, revealing enforcement gaps. Singapore sought plantation maps to identify polluters and enhance accountability under this law, underscoring the importance of strong air quality regulations and regional cooperation. Because air pollution does not recognize national boundaries, this extraterritorial approach is a key reason Thailand’s Draft Clean Air Act is expected to show similar principles.

Potential Impacts of the Draft Clean Air Act on Businesses

Due to the ongoing nature of the legislative process, it is difficult to forecast with precision how the Draft Act could impact businesses in Thailand and further afield. Businesses contributing to air pollution in Thailand may face financial penalties, potential litigation, reputational damage, or a combination thereof, depending on the strength of the Draft Act. Further, if businesses in Thailand have operations in surrounding countries that result in transboundary air pollution impacting Thailand, they too may face potential financial penalties and litigation under the Draft Act. This, however, depends on whether or not the Draft Act will have extraterritorial reach when adopted.

In various other countries, regulatory authorities are increasingly holding companies accountable for their environmental impact, and fines are imposed on those found responsible for activities resulting in air pollution. As one example, the New South Wales Land and Environment Court recently fined one of Australia’s largest gold mines AUS$350,000 for breaching air pollution regulations by exceeding dust limit regulations on five occasions at a ventilation site.

Preparing Businesses for the Draft Clean Air Act

To prepare for the introduction of the Draft Clean Air Act, businesses in Thailand should take proactive measures to mitigate the impacts their operations have on the environment. This includes the following recommendations:

Adopting cleaner production techniques to lower air pollution; for example, investing in air filtration systems to ensure harmful pollutants are eradicated at the source.

Reviewing elements of their supply chain to ensure that suppliers are adhering to clean air practices; for instance, agricultural businesses should work with farmers to reduce reliance on agricultural burning by exploring cleaner alternatives for land clearing and biomass removal.

Training and developing their people to understand the negative impacts of air pollution.

Ensuring your operational procedures align with recognized international standards.

Furthermore, businesses should stay alert to governmental regulations and initiatives, including the Draft Clean Air Act, to ensure compliance with new, stricter emission standards. Ideally, businesses should be exploring methods to reduce air pollution before the Draft Clean Air Act comes into force to ensure broad compliance. By taking these steps to mitigate air pollution, businesses in Thailand can contribute to improving air quality and safeguarding public health, rather than be the cause of the problem, while avoiding potential fines, litigation and reputational harm in Thailand and further afield.

Concluding Remarks on the Draft Clean Air Act

As we explained throughout this legal update, it is challenging to predict the precise regulations that could be included in the finalized version of the Draft Clean Air Act. The legislative process involves multiple stages of review, amendment, and consultation, which can lead to significant changes before the Draft Act is officially enacted into law in Thailand.

Nonetheless, while the implementation of an act specifically advocating for clean air will not entirely resolve the complex issue of air pollution in Thailand and its neighboring countries, the Draft Act represents a crucial, positive step forward in the fight against air pollution and its detrimental impacts, because for the first time in Thailand, it will establish the basic human right to clean air under Thai law. As such, it will embody the collective to lay a strong foundation for ongoing efforts to improve air quality in the country. It will also empower businesses, individuals, and local communities to take proactive steps in reducing pollution and protecting the environment.

This article was drafted by Chumbhot Plangtrakul, Ronnarit Ariyapattanapanich, and Joseph Willan, with research assistance from Lapon Lertpanyaroj, Premchama Lamiedvipakul, and Worrawantra Nuam-In.

[1] These political parties are Palang Pracharath, Bhumjaithai, Pheu Thai, Kao Klai, and the Democrat Party

Shareholder Disputes in Medical and Dental Practices in Australia

Key Takeaways

Shareholder disputes arise from circumstances both anticipated and unanticipated at the time of formation of a business relationship.

Shareholder disputes cause major disruptions to a business, which can ultimately harm the value of the investment or put the ongoing existence of the company at risk.

The risks of a shareholder dispute arising, and the impact of it if it does, can be mitigated by ensuring a comprehensive shareholders’ agreement is in place.

If a dispute arises, resolution can be more readily achieved where share valuation methods, dispute resolution mechanisms, and shareholders’ roles and rights are clearly defined.

Shareholder Disputes: Anticipating the Causes and Navigating the Challenges

Shareholder disputes are a common occurrence in today’s business landscape. These conflicts often emerge from complex and interrelated issues that are usually not anticipated during the initial stages of developing the business. The context in which they arise, and the potential consequences, can make these disputes very difficult to resolve without significant disruption to the business and its owners.

Such disputes can also severely impact a business’s operational efficiency, market value, and growth potential. Many disputes result in prolonged conflicts (including costly litigation) which erode shareholder value, tarnish professional reputations and, without resolution, can become a zero-sum game.

Shareholders should anticipate the challenges businesses face, the common causes of disputes and how they might be resolved with a view to implementing a number of protections that might facilitate swift, cost-effective resolutions and preserve the value of their investments (of time, money, effort and relationships) if a dispute arises.

How Can the Prospect of a Shareholder Dispute be Minimised?

No business endeavour should be undertaken without at least a reasonable understanding of the following:

The roles and responsibilities of each shareholder in the business.

What is being contributed by each shareholder, and how they will be remunerated or compensated for those contributions.

The circumstances in which each shareholder might choose to exit and the consequences of doing so.

How the business might be valued if shareholders propose to sell their shares, or a buyout is ordered by the court to ensure that the shareholders’ original intentions and respective contributions over time are reflected in that outcome and to prescribe the method of calculation that a valuer must adopt (remembering any agreement can be varied later, if necessary, and may not be binding on the court).

What rights of access each shareholder has to the books and records of the business.

When the court might intervene in the affairs of a company and what powers it has.

What duties shareholders who are also (or are related to) directors or employees might owe to the company, and what restraints might arise on their conduct (including after they leave the company).

It will be impossible to effectively clarify (or agree) on those matters once a dispute has arisen or seems likely to arise. They must be dealt with upfront, regardless of the perceived strength of the parties’ relationship, likelihood of commercial success, or nature and size of the business.

Why Do Shareholder Disputes Arise?

When Business Goals Diverge

Divergent goals among shareholders pose significant challenges. As businesses evolve, shareholders may develop conflicting visions for the company’s future. Changes in shareholders’ personal circumstances can misalign what were once shared objectives, leading to disagreements over growth, risk and direction.

Stalemates arising due to incompatible goals can hinder progress and profitability or even bring trading to a halt altogether.

When Corporate Governance Deteriorates

Corporate mismanagement can be both the cause and product of shareholder disputes. In the first case, poor governance can lead to inefficiencies and mismanagement that may contribute to a dispute. In the latter case, by the time a dispute has arisen it can be difficult to manage business functions that require shareholder cooperation. That difficulty can create or compound inefficiencies and mismanagement.

Disputes often arise when there is ambiguity or disagreement over governance structures or a misunderstanding of the duties owed by stakeholders. Effective corporate governance requires clearly defined roles, responsibilities and decision-making processes, yet these elements are often scrutinised only after disagreements have arisen.

When Interpersonal Relationships Break Down

Interpersonal relationships are often collateral damage to shareholder disputes, if not themselves a contributing factor. That element can exacerbate conflicts, emotionally bias parties, and make objective and solution-oriented resolutions much harder to accomplish.

Interpersonal incompatibility is frequently not apparent at the start of a venture and is not just limited to differing personalities. Isolated clashes, such as differences in management style, communication issues or a breakdown in trust, might be all that is needed to spark tension.

When Shareholders Disagree About Money

Financial disagreements are frequently the trigger point for bitter disputes. These might surround disagreements about profit distribution, investment strategies and financial transparency. Disagreements about money are, in many respects, also more prone to heightened emotional influence.

The money factor between shareholders is unavoidable, even if it is only a minor concern at the early stages of business. After a business has had the opportunity to develop (and typically after the shareholders have invested a significant amount of time and labour into that development), the attitude of shareholders can shift, and perceived entitlements can later become irreconcilable.

How can Shareholders Mitigate Risk Before it Arises?

Anticipating the common causes of shareholder disputes is useful for identifying potential risks early and taking proactive measures to address or avoid them.

Understanding your legal rights, stakeholder obligations and potential risks is crucial for safeguarding your investment. Taking stock of your governing documents is key to making informed decisions in relation to risk factors. During prosperous times, the importance of having a robust legal framework governing shareholder relations is all too often underestimated. This oversight can jeopardize investments if relationships turn sour in the future.

While the benefit of hindsight and objective high-level speculation might make these things seem obvious, it is very common for these factors to go unchecked until it is too late in the game.

Fundamentally, the shareholders should ensure a comprehensive shareholders’ agreement is in place, dealing with the issues described above, so that there is no doubt about the parties’ respective rights and obligations.

What if a Dispute Does Arise?

Some disputes are inevitable. Nonetheless, many can be resolved before undue time and money are wasted where the parties’ rights, obligations and causes for complaint are clearly defined; the room for the dispute to escalate is reduced; and the parties are prepared to agree to a sensible approach to resolution. An early and less costly resolution might be achieved where the following occurs:

There is a dispute resolution mechanism agreed to between the parties (in the shareholders’ agreement) that:

forces the parties to engage in good faith settlement negotiations before the dispute is escalated to litigation, arbitration or some other formal determination process; and

predetermines how shares will be valued if a dispute arises, so that the ultimate outcome of an escalated dispute can be anticipated by both sides with greater certainty and considered during negotiations.

There is an early identification of what shareholders want out of the dispute (which might require advice about their rights and obligations).

All parties are prepared to commit to identifying some mutually acceptable outcome, or an independent determination of the dispute, particularly if the relationship between the parties is to continue (which may be advantageous for various reasons).

The parties settle on an approach that seeks to preserve the value of the business (including the shareholders’ shares), rather than harming the other parties (as is often a motivating factor).

If the relationship cannot be salvaged, it is possible to agree to a carefully managed exit from the business, possibly including appropriate restraints.

ASIC Trialling Fast-Tracked Initial Public Offerings

On 10 June 2025, the Australian Securities and Investment Commission (ASIC) announced that it was commencing a two-year trial of a fast-tracked initial public offering (IPO) process (Fast-Track Process).

This announcement comes in response to the decline in IPOs and public companies in Australia.1

Who is Eligible for the Fast-Track Process?

To be eligible for the Fast-Track Process, entities planning an IPO will be required to have:

A minimum projected market capitalisation at quotation of at least AU$100 million; and

No securities that will be subject to escrow imposed by the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX),

(Eligible Entities or Eligible Entity).

What is the Fast-Track Process?

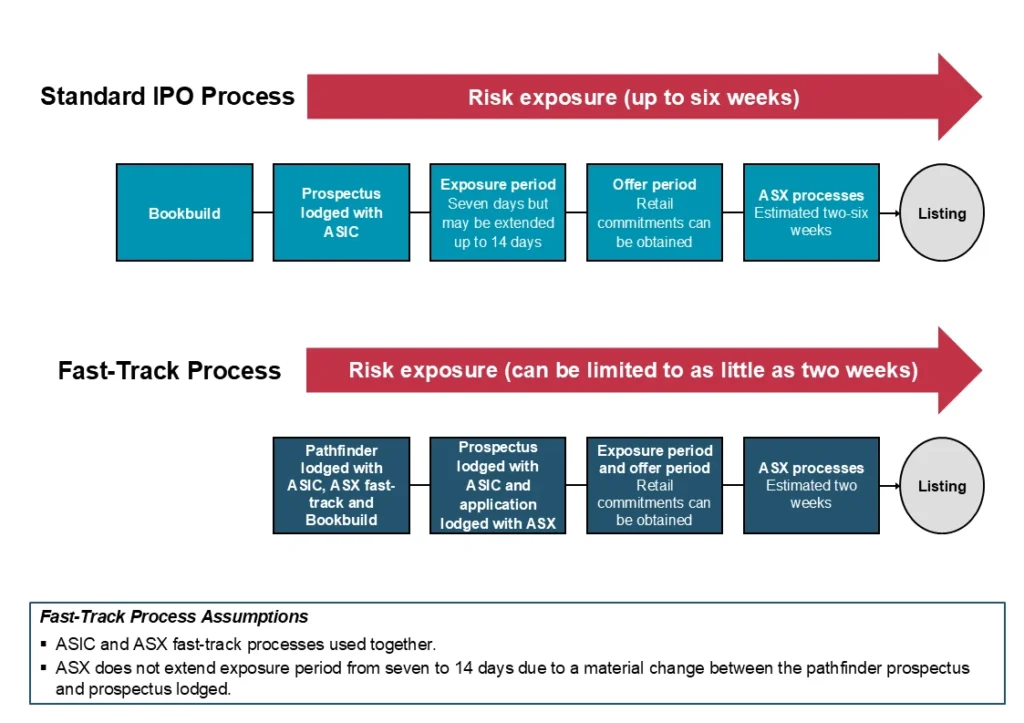

Under a standard IPO process, once a prospectus is lodged with ASIC for review, the prospectus is subject to a mandatory exposure period of seven days which is often extended to 14 days. Applications for securities offered under the prospectus can only be accepted after the exposure period ends.

Under the Fast-Track Process, Eligible Entities can provide a pathfinder prospectus (being a prospectus that is provided to institutional investors and omits pricing information) to ASIC at least 14 days prior to formal lodgement.2 As ASIC will be provided with an opportunity to review the pathfinder prospectus prior to lodgement, it will generally not need to extend the seven day exposure period after formal lodgement of the IPO prospectus.

However, if any new material information has been included in the prospectus or has come to light since the pathfinder prospectus was lodged with ASIC, the seven-day exposure period may still be extended. Accordingly, the prospectus lodged should not differ in any material respect from the pathfinder prospectus except for pricing, offer metrics and financial information, and as otherwise agreed with ASIC.

ASIC has also announced a “no-action” position meaning that ASIC does not intend on taking action where Eligible Entities accept an application for securities during the exposure period (which would be in contravention of subsections 727(3) or (6) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth)).3

Alignment with ASX Fast-Track Process

The Fast-Track Process aligns with the ASX’s changes to Guidance Note 1 which took effect from 30 May 2025.

Under a standard IPO process, ASX will not commence review of a listing application until an entity lodges its prospectus with ASIC. Therefore, it may take up to six weeks from formal lodgement before a listing decision is made.

Under the revised Guidance Note 1, ASX may agree to “front end” its review where an Eligible Entity lodges a draft listing application (and accompanying draft documents) with the ASX no less than four weeks prior to the formal lodgement date of the prospectus with ASX (in the same form as lodged with ASIC).4 ASX estimates that official quotation of the Eligible Entity’s securities would occur two weeks after formal lodgement of the prospectus with the ASX.

Eligible Entities are encouraged to discuss the Fast-Track Process with ASX at the earliest opportunity to ensure that ASX is agreeable and that its proposed timetable can be accommodated. We recommend raising the Fast-Track Process as part of any in-principle advice application lodged with the ASX prior to formal lodgement of the prospectus. ASX may reject the Fast-Track Process where the pathfinder prospectus and other documents are not near final drafts.

What are the Benefits of the Fast-Track Process?

The Fast-Track Process allows Eligible Entities to become listed on ASX faster.

As the Fast-Track Process provides ASIC with an opportunity to informally review a pathfinder prospectus before it becomes publicly available, ASIC may be able to raise concerns earlier in the process, thereby potentially reducing the need for replacement or supplementary prospectuses.

Additionally, the Fast-Track Process reduces the period between the pre-commitment of institutional investors to acquire shares in the IPO and the commencement of trading of the Eligible Entity’s securities on ASX.

Accordingly, the Fast-Track Process should reduce the period during which institutional investors are “on risk” by decreasing the time that they are exposed to adverse market fluctuations while ASIC and ASX review the Eligible Entity’s prospectus and listing application.

As the share price offered to institutional investors is often discounted to accommodate for risk, the reduction in time between institutional investor pre-commitment and quotation may lead to better pricing outcomes for Eligible Entities.

Risk Exposure of Institutional Investors Under a Standard IPO Compared to a Fast-Track Process

Source: Aimee Foster, K&L Gates, 2025

Conclusion

The Fast-Track Process trial is indicative of ASIC’s attitude towards streamlining the process to encourage IPO activity. However, whether there will be an increase in the number of Australian IPOs over the next two years is yet to be seen.

Footnotes

1 ASIC Discussion Paper: Australia’s evolving capital markets: A discussion paper on the dynamics between public and private markets, released on 26 February 2025.2 An Eligible Entity wishing to use the Fast-Track Process should email its pathfinder prospectus to [email protected] This does not preclude other third parties from taking action for this conduct.4 ASX Guidance Note 1, section 2.6.

Cross-Border Catch-Up: Understanding International Anti-Harassment Training Laws [Podcast]

In this episode of our Cross-Border Catch-Up podcast series, Maya Barba (San Francisco) and Kate Thompson (New York, Boston) discuss the intricacies of mandatory anti-harassment training and policies across various countries. Kate and Maya provide an overview of the requirements in Australia, China, South Korea, India, Romania, and Peru, among other countries. The speakers review which employees need to be trained, the duration and frequency of required training programs, and the types of harassment, including sexual harassment, discrimination, and bullying, that these trainings must cover.

HealthBench: Exploring Its Implications and Future in Health Care

As we noted in our previous blog post, HealthBench, an open-source benchmark developed by OpenAI, measures model performance across realistic health care conversations, providing a comprehensive assessment of both capabilities and safety guardrails that better align with the way physicians actually practice medicine.

In this post, we discuss the legal and regulatory questions HealthBench addresses, the tool’s practical applications within the health care industry, and its significance in shaping the future of artificial intelligence (AI) in medicine.

Legal and Regulatory Implications

Practice of Medicine Concerns

HealthBench’s sophisticated evaluation of AI models in health care contexts raises important questions about the unlicensed practice of medicine and corporate practice of medicine doctrines.

By measuring how models respond to clinical scenarios—particularly in areas like emergency referrals and clinical decision-making—HealthBench provides valuable metrics for assessing when an AI system might cross the line from providing general health information to engaging in activities that could constitute medical practice.

Unlike multiple-choice tests, which primarily assess factual knowledge, HealthBench evaluates models on the types of interactions that might trigger regulatory scrutiny, such as providing personalized clinical advice or making what could be interpreted as medical recommendations, as well as suggesting diagnoses that could merit higher reimbursement. This distinction is crucial as state medical boards and regulators develop frameworks for AI oversight that consider functional capabilities rather than simply knowledge recall. As we highlighted in Epstein Becker Green’s overview of Telemental Health Laws, the regulatory landscape for digital health varies significantly across jurisdictions, requiring careful navigation of different state-specific requirements regarding corporate practice of medicine and the provision of telehealth services.

The benchmark’s ability to distinguish between appropriate responses to health care professionals versus general users also helps clarify when models are operating as clinical decision support tools versus direct-to-consumer health resources, a distinction increasingly important for compliance with state-specific corporate practice of medicine restrictions.

The benchmark can also serve to guide whether a model is biased towards diagnoses with higher risk scores or reimbursement levels, which informs fraud and abuse considerations. The benchmark is also important on the payer side as AI is increasingly used for utilization management and prior authorization, which requires consideration of the individual clinical profile for the determination of medical necessity for an item or service rather than simply relying on a clinical decision-making tool.

EU AI Act and High-Risk Classification

Under the EU AI Act, AI systems intended for use as safety components in medical devices or for providing medical information used in clinical decision-making are classified as “high-risk.” HealthBench’s comprehensive evaluation framework—particularly its assessment of emergency referrals, accuracy, and safety—provides metrics directly relevant to demonstrating compliance with the risk management, technical documentation, and human oversight requirements imposed on high-risk AI systems under the Act.

The benchmark’s measurement of context awareness and the ability to recognize when uncertainty is present aligns with the Act’s requirements that high-risk AI systems appropriately consider limitations in their design and communicate these effectively to users. These capabilities cannot be meaningfully assessed through multiple-choice tests but are captured in HealthBench’s conversational evaluation approach.

Addressing Bias and Fairness

HealthBench’s global health theme evaluates whether models can adapt responses across varied health care contexts, resource settings, and regional disease patterns. This assessment helps identify potential biases in model responses that might disadvantage users from underrepresented regions or health care systems.

Traditional medical knowledge tests have often reflected Western medical education and practice patterns, potentially obscuring biases in how AI systems approach global health questions. HealthBench’s development with physicians from 60 countries who collectively speak 49 languages provides a foundation for assessing model performance across diverse populations, though further work on explicit bias evaluation remains an area for continued development.

Health Care Industry Implementation Considerations

Clinical Workflow Integration

HealthBench evaluates whether models can safely and accurately complete structured health data tasks—such as drafting medical documentation or enhancing clinical decision-making. These metrics help health care institutions assess how effectively AI models might integrate into existing clinical workflows and identify potential friction points before deployment. As the FDA continues to refine its approach to digital health technologies, the ability to demonstrate robust performance on realistic clinical tasks becomes increasingly important for regulatory clearance and market adoption.

Unlike knowledge-based examinations, HealthBench measures capabilities that directly translate to potential clinical applications, providing more actionable insights for implementation planning.

Patient-Provider Communication

The expertise-tailored communication theme measures whether models can distinguish between health care professionals and general users, tailoring communication appropriately. This assessment is crucial for deployment decisions, as models that cannot effectively modulate their responses based on user expertise may create confusion or misunderstanding in clinical settings.

Traditional benchmarks provide little insight into these communication capabilities, which represent core skills for physicians but are rarely captured in standardized testing environments. As ambient listening AI is generating more interest in the health care ecosystem, this benchmark can help to guide whether the information captured represents an accurate clinical picture or is biased. For example, this is particularly relevant in the contexts of complex clinical profiles where poor clinical decision-making could result in medical malpractice. Additionally, this benchmark would also be relevant in the context of clinical profiles where improper coding could impact claims submission that yield higher reimbursement. On the other hand, the benchmark can help practitioners understand whether their ambient listening tools streamline their practice and permit them to be more efficient.

Risk Management and Liability

HealthBench’s evaluation of model reliability—particularly the “worst-at-k” performance that measures how quickly worst-case performance deteriorates with sample size—provides essential metrics for health care risk management. The benchmark reveals that even frontier models like o3, while achieving an overall score of 60%, see their worst-at-16 score reduced by a third, indicating significant reliability gaps when handling edge cases.

This type of risk assessment is impossible with conventional multiple-choice evaluations, which typically report only aggregate scores without revealing the frequency or severity of concerning responses—a critical oversight when considering clinical deployment.

Future Directions and Limitations

While HealthBench represents a significant advancement in health care AI evaluation, it focuses primarily on conversation-based interactions rather than specific clinical workflows that may utilize multiple model responses. The benchmark also does not directly measure health outcomes, which ultimately depend on implementation factors beyond model performance alone.

Real-world studies measuring both quality of model responses and outcomes in terms of human health, time savings, cost efficiency, and user satisfaction will be important complements to benchmark evaluations like HealthBench.

Conclusion

HealthBench establishes a new standard for evaluating AI systems in health care, one that emphasizes real-world applicability, physician validation, and multidimensional assessment. By moving beyond the artificial constraints of multiple-choice tests toward evaluations that mirror authentic clinical practice, HealthBench provides a more meaningful and rigorous assessment of AI capabilities in health care contexts.

As health care organizations, technology developers, and regulators navigate the rapidly evolving landscape of health care AI, benchmarks like HealthBench provide important frameworks for ensuring that innovation advances alongside safety, quality, and ethical deployment.

By grounding progress in physician expertise and realistic scenarios, HealthBench offers a valuable tool for assessing both performance and safety as health care AI continues to evolve—ultimately supporting the responsible development of AI systems that can meaningfully improve human health.

Treasury’s Latest Moves: Fast-Track for Foreign Investors & Outbound AI Investment Inquiry

The U.S. Department of the Treasury (“Treasury”) has been active in the context of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States’ (“CFIUS”) and the Outbound Investment Security Program (“OISP”). The main updates relate to: (1) Treasury’s announcement of an intent to launch a Fast Track Pilot Program under CFIUS for Foreign Investors; and (2) the review of Silicon Valley firm Benchmark Capital’s investment in Manus AI, a Chinese-linked startup.

Fast Track Pilot Program

On May 8, 2025, Treasury announced its intent to establish a fast track process to facilitate greater investment in U.S. businesses from allies and partners, as outlined in the America First Investment Policy Memorandum issued early in the Trump Administration[1] pursuant to the Policy’s objective of maintaining a strong, open investment environment for such parties.

A key feature of the envisioned fast track process involves the launch of a “Known investor portal” through which CFIUS will be able to collect information from foreign investors in advance of a filing. The Known investor portal can potentially be a useful tool for certain investors that either frequently file, or are competing for an opportunity and will benefit in a bid process from Known investor status. Through this approach, Treasury expects not only to maintain and enhance an open investment environment that benefits the U.S. economy, but also to ensure the Committee is able to identify and address any national security risks that may arise from such foreign investments.

The press release regarding Treasury’s intent to launch the Fast Track Pilot Program for Foreign Investors can be accessed through the following link: https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sb0136.

Review of Benchmark Capital’s Investment in Chinese Startup Manus AI

Treasury is also reviewing a $75 million investment made by Silicon Valley based Benchmark Capital (“Benchmark”), in Manus AI, a Chinese-linked startup (“Manus”).

According to sources, Benchmark received an inquiry from Treasury on “whether its financial backing of Manus AI falls under new restrictions aimed at investments in artificial intelligence and other sensitive technologies destined for ‘countries of concern’.”[2] Such inquiry would come in the context of Treasury’s enforcement of the OISP, under which U.S. entities must notify the Treasury of investments that could “accelerate and increase the success of the development of sensitive technologies” in ways that might harm U.S. interests[3].

Benchmark hasn’t responded publicly with respect to the inquiry, but is expected to argue that notification is unnecessary based on legal advice it had received before investing in Manus.

The issues raised include: (i) whether Manus develops its own AI models (in which case it would be subject to the notification requirement) or if it builds products based on pre-existing models; and (ii) whether Manus can be deemed a Chinese-based company, considering its parent organization is incorporated in the Cayman Islands and the company employs staff in the U.S., Singapore, Japan and China, as well as stores data on cloud servers run by western firms. For many transactions, these and related questions can be difficult to answer, and we are guiding parties through strategies and practices for how to do so.

According to sources, the case highlights the growing tension between promoting technological innovation and protecting national security, and it could set an important precedent for future outbound investment strategies, reviews and national security policy as a whole.

[1] For more information, see: Trump Administration issues America First Investment Policy – Insights – Proskauer Rose LLP. Accessed 6/3/2025.

[2] Cited from: Treasury Probes Benchmark’s Investment in Chinese-Linked AI Startup Manus. Accessed 6/3/2025.

[3] For more information, see: U.S. Department of the Treasury issues final regulations implementing Executive Order 14105 Targeting Tech Investment in China – Insights – Proskauer Rose LLP. Accessed 6/3/2025.

Amsterdam’s New Permit Requirement for Mid-Range Rentals: Key Considerations for Landlords

Beginning July 1, 2025, the city of Amsterdam will implement a permit requirement for so-called “mid-range” rental properties. This regulatory change is aimed at preserving the availability of affordable rental housing for middle-income residents. For landlords with properties in this segment, the new rules introduce a number of compliance obligations, as well as certain practical challenges that merit careful attention.

Under the new regime, tenants seeking to rent a mid-range property (defined as those with a base rent up to €1,184.82 per month or with between 144 and 186 property valuation points) will need to obtain a housing permit prior to moving in. This permit requirement also applies to certain newly built properties for which the municipality has capped the rent in an agreement with the developer or the terms of the ground lease. The permit will only be issued if the tenant’s income at the start of the lease does not exceed €81,633 per year for single households or €89,821 for households with more than one occupant. The city intends to use this mechanism to ensure that these homes remain accessible to the target group of middle-income earners. Any changes in income after the initial review will not lead to a re-evaluation of the permit.

For landlords, compliance with the permit requirement is mandatory. It will not be permissible to rent out a qualifying property to a tenant who has not secured the necessary permit. In addition, landlords are expected to inform prospective tenants about the property’s valuation points, which in turn set the maximum allowable rent. These requirements are likely to add a layer of administrative complexity to the leasing process.

There are several potential risks for landlords who fail to adapt to the new rules. Most notably, non-compliance may result in fines or other enforcement measures by the municipality. While Amsterdam has indicated that it will take a relatively lenient approach to enforcement in the early months following the introduction of the permit requirement, landlords should not assume this grace period will last indefinitely.

Another consideration is the potential for rental income loss due to delays. The process of applying for and receiving a housing permit can take several weeks. It will be important for landlords to communicate proactively with prospective tenants about the new requirement and to properly address this in the lease agreement.

Finally, landlords should be prepared for increased administrative and record-keeping obligations. The new rules will require careful documentation of property valuation points and tenant income eligibility. In the short term, this may require additional time and resources, particularly as the market adjusts to the new regulatory landscape.

In summary, while the new permit regime presents clear challenges, it can also offer an opportunity for diligent landlords to distinguish themselves by ensuring transparency and compliance in their leasing practices. Those with questions about how these changes may affect their portfolio, or who require assistance navigating the new requirements, should consult with an experienced Dutch real estate counsel.

Canada Refines Focus on Greenwashing Prosecutions

Recently, the Canadian Competition Bureau published updated guidelines concerning its approach to environmental claims following last year’s amendments to Canadian law that specifically targeted greenwashing. These guidelines are not especially surprising–there is a stated focus on four types of claims that will be the subject of enforcement: (1) “false or misleading representations”; (2) “product performance claims”; (3) “claims about the environmental benefits of a product”; and (4) “claims about the environmental benefits of a business or business activity”–all of which are grounded specifically in a statutory provision. The guidelines further identify six principles that companies should abide by in order to avoid prosecution: (1) “Environmental claims should be truthful, and not false or misleading”; (2) “Environmental benefits of a product and performance claims should be adequately and properly tested”; (3) “Comparative environmental claims should be specific about what is being compared”; (4) “Environmental claims should avoid exaggeration”; (5) “Environmental claims should be clear and specific–not vague”; and (6) “Environmental claims about the future should be supported by substantiation and a clear plan.” All of these principles are generally self-explanatory, and should be part of good business practices.

However, more than the specific guidance offered, what is perhaps more significant is that the Canadian Competition Bureau has chosen to issue these detailed guidelines in response to the greenwashing amendments. While the Competition Bureau often issues such guidelines, it does so in circumstances when legal amendments are deemed significant and where enforcement may be considered a priority. This development therefore indicates the extent of the focus on greenwashing by the relevant Canadian regulators.

Recently, the Act was amended to include two new provisions that explicitly address environmental claims. These new provisions build on the provision of the Act that requires that certain claims be evidence-based. The Bureau is therefore taking this opportunity to describe our approach to environmental claims specifically as they relate to the deceptive marketing provisions of the Act.Footnote2 However, readers are reminded that other laws enforced by the Bureau, including the Consumer Packaging and Labelling Act and the Textile Labelling Act, also prohibit certain types of deceptive representations, and may be relevant to environmental claims.

competition-bureau.canada.ca/…

UK ICO Publishes Draft Guidance on Internet of Things Products and Services

On June 16, 2025, the UK Information Commissioner’s Office (the “ICO”) published its draft guidance on Internet of Things (“IOT”) products and services (the “Guidance”). Through the Guidance, the ICO aims to provide clarity to manufacturers and developers of smart products, such as smart speakers and Wi-Fi fridges, to ensure they create products that comply with data protection law. The Guidance covers key areas such as:

Types of Information: The Guidance explains the different types of personal data which may be processed by IoT products and services, including health, biometric and location data, and how such data may be used and collected.

Accountability: The ICO considers areas of accountability in the context of IoT products and services, such as the controller and processor relationship, privacy by design, and the use of IoT products and services by children.

Lawful Processing: The Guidance considers the application of the lawful bases and the special category conditions of processing under the UK General Data Protection Regulation (the “UK GDPR”) to of IoT products and services, and gives examples of how manufacturers and developers can seek to ensure that freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous consent is obtained by consumers.

Fair Processing: The ICO encourages manufacturers and developers to consider how personal data is processed, focusing on key issues such as necessity, proportionality and purpose limitation.

Transparency: The Guidance includes examples for manufacturers and developers on how to inform consumers of how they collect, use and share personal data.

Security: The Guidance stresses the importance of implementing and maintaining appropriate technical and organizational measures, providing examples of such including encryption and multi-factor authentication.

Data Subject Rights: The ICO reminds manufacturers and developers of their responsibility to inform consumers of their data subject rights under the UK GDPR.

The ICO’s intention behind the Guidance is to empower organizations to consider responsible use of information and compliance with data protection laws. However, the ICO has warned manufacturers and developers that it is “closely monitoring compliance” and will be “ready to act” where it believes “corners are being cut or personal information is being collected recklessly.”

The ICO has asked for manufacturers, developers and the wider tech industry to share their views on the draft Guidance, which will be open for consultation until September 7, 2025.

Overriding Interest Summer 2025

Welcome to the latest edition of Overriding Interest.

Inside this issue:

New Joiners

Articles of Interest

Events

Cases Studies

Pro Bono Cases

To access the full edition of this newsletter, please click here.

Anzeigen Digital – BaFin Ermöglicht Zukünftig Digitale Anzeigen zu Geldwäschebeauftragten

Die Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (BaFin) öffnet ihr Portal der Melde- und Veröffentlichungsplattform (MVP-Portal) zukünftig auch für geldwäscherechtliche Anzeigen.Konkret betrifft dies alle im Voraus anzeigepflichtigen Sachverhalte rund um den Geldwäschebeauftragten und dessen Stellvertreter, also:

• die Bestellung;• etwaige Änderungen (z.B. Kontaktdaten);• die Entpflichtung.

Zur Vornahme von Anzeigen auf diesem digitalen Weg bedarf es lediglich einer Registrierung auf dem MVP-Portal und einer Zulassung zum sog. „Fachverfahren‚ Geldwäscheprävention und Terrorismusfinanzierung“. Die digitale Anzeige soll voll wirksam sein und eine Übersendung per Post ist zukünftig nicht mehr erorderlich. Das neue Verfahren steht allen Verpflichteten, die unter Aufsicht der BaFin stehen, seit dem 13. Juni 2025 offen.