Anzeigen Digital – BaFin Ermöglicht Zukünftig Digitale Anzeigen zu Geldwäschebeauftragten

Die Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (BaFin) öffnet ihr Portal der Melde- und Veröffentlichungsplattform (MVP-Portal) zukünftig auch für geldwäscherechtliche Anzeigen.Konkret betrifft dies alle im Voraus anzeigepflichtigen Sachverhalte rund um den Geldwäschebeauftragten und dessen Stellvertreter, also:

• die Bestellung;• etwaige Änderungen (z.B. Kontaktdaten);• die Entpflichtung.

Zur Vornahme von Anzeigen auf diesem digitalen Weg bedarf es lediglich einer Registrierung auf dem MVP-Portal und einer Zulassung zum sog. „Fachverfahren‚ Geldwäscheprävention und Terrorismusfinanzierung“. Die digitale Anzeige soll voll wirksam sein und eine Übersendung per Post ist zukünftig nicht mehr erorderlich. Das neue Verfahren steht allen Verpflichteten, die unter Aufsicht der BaFin stehen, seit dem 13. Juni 2025 offen.

European Commission Kick Starts Overhaul of EU Telecom Law

“Look, if you had one shot or one opportunity to seize everything you ever wanted in one moment, would you capture it or just let it slip?” asks Eminem in his song “Lose Yourself”. This year might provide just one of those once-in-a-life time opportunities for EU telecom law.

Many stakeholders have been calling for a reform of EU telecom law for some time, venting their frustration at the EU legislature. Earlier this month, finally, the European Commission launched a public call for input on the review of the EU Electronic Communications Code (EECC) and the adoption of a new Digital Networks Act (DNA), which could replace the EECC (and other regulatory instruments) entirely.

The European Commission (and specifically the Directorate‑General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology, Unit B1) believes that: “as laid out in the Letta, Draghi and Niinistö reports, and in the Commission’s Communication A Competitiveness Compass for the EU, a cutting-edge digital network infrastructure is critical for the future competitiveness of Europe’s economy, security and social welfare” and “a modern and simplified legal framework … is key”. Such a regulatory change was first explored in the Commission’s 2024 White Paper “How to master Europe’s digital infrastructure needs?” (see our thoughts on the white paper here: The European Commission Publishes a New Master Plan for Europe’s Digital Infrastructure)

The new public call for input now gives more colour to the Commission’s plans on the proposed DNA, which is likely to focus on the following potential areas for reform:

Simplification – The DNA could aim to:

Reduce existing reporting obligations (up to 50%) and to remove unnecessary regulatory burdens (e.g. requirements for providers of business-to-business services and IoT services) and re-focusing Universal Service obligations on affordability aspects;

Repeal and recast various related legislative instruments (e.g. EECC, BEREC Regulation, Open Internet Regulation, Radio Spectrum Policy Programme);

Introduce a simplified authorisation regime and a reduced and more harmonised set of common authorisation conditions, so that operators can more easily operate cross-border, and further coordination and common implementation of other applicable requirements for providers (e.g. security and law enforcement);

Harmonise end-user protection rules;

Create a more fertile ground for pan-European / cross-border telecom consolidation.

Spectrum – The DNA could propose:

To strengthen the peer review procedure, ensure timely authorisation of spectrum on the basis of an evolving roadmap and set common procedures and conditions for the national authorisation of spectrum;

Longer license duration and easier renewals, and to gear spectrum auction designs towards spectrum efficiency and network deployment as basis for the early introduction of 6G;

Flexible authorisation including spectrum sharing (in line with EU competition law principles) and facilitate requests for spectrum harmonisation;

To reinforce EU sovereignty and solidarity regarding harmonisation of spectrum, and when addressing cross-border interferences from third countries; and

To establish a level playing field for satellite constellations used for accessing the EU market. Separately, the European Commission is also running a parallel call for input on the review of the EU regulatory framework for licensing mobile satellite services (MSS) spectrum.

Level Playing Field – the DNA could include:

Creating effective cooperation among the actors of the broader connectivity ecosystem (e.g. cloud services and infrastructure providers) giving the empowerment of NRAs/BEREC to facilitate cooperation (e.g. through a dispute resolution mechanism) under certain conditions and in duly justified cases; and

A clarification of the Open Internet rules concerning innovative services (such as e.g. network slicing and in-flight connectivity), e.g. by way of interpretative guidance, while fully preserving the Open Internet principles.

Access Regulation – the DNA could propose:

To apply ex-ante regulation (i.e. access conditions at national level) after the assessment of the application of symmetric measures (e.g. Gigabit Infrastructure Act or other forms of already existing symmetric access) only as a safeguard, following a market review based on the existing three criteria test and a geographic market definition, and subject to the review of the Commission, BEREC and other NRAs, with the Commission retaining veto powers;

To simplify and increase predictability in the access conditions by introducing a pan-EU harmonised access product(s) with pre-defined technical characteristics, which would be a default remedy imposed on operators with significant market power if competition problems were identified; and

To accelerate copper switch-off by providing a toolbox for fibre coverage and national copper switch-off plans, and by setting an EU-wide copper switch-off date as default, along with a derogation mechanism to protect end-users with no adequate alternatives.

Governance: in order to reinforce the Single Market dimension, the DNA could consider an enhanced EU governance with sufficient administrative and regulatory capacity (consultative or decision-making competences), through enhancing respective roles of BEREC, BEREC Office and RSPG to address various pan-European tasks and further the digital single market.

The Commission is consulting widely to gather information and ensure that the public interest is well reflected in the design of the DNA. In addition, multiple consultation activities have been already carried out in Brussels and at national level, including through three studies commissioned to external consultants, covering the following areas:

Regulatory enablers for cross border networks/ completing the single market;

Access Policy including review of the Relevant Markets Recommendation, and review of access provisions of the EECC; and

Financing issues, including the future of the Universal Service.

As integral part of the studies, further interaction with stakeholders is envisaged through e.g. interviews, questionnaires and workshops in Brussels. The final report of the studies is planned to be published once finalised in Q4 2025 together to the impact assessment of the detailed proposals for the DNA.

However, EU member states remain skeptical about the Commission’s more ambitious plans to overhaul telecom rules, especially when it comes to simplification, governance and management of national resources (such as spectrum and numbering). Therefore, the Commission is keen to engage, as appropriate, also with BEREC and the RSPG, and through ad hoc workshops with national authorities at member state level.

The deadline for responding to the call for input is 11 July. This provides the last official opportunity to try to influence the Commission’s thinking before the publication of the detailed proposals for a new EU telecom law because the EU Commission is not planning another official public consultation before publishing the DNA proposal… would you capture it or just let it slip?

URS v BDW [2025]: Supreme Court Confirms Consultants’ Duty to Developers for Historic Defects

Summary

The UK Supreme Court’s (Court) decision in URS Corporation Ltd v BDW Trading Ltd [2025] UKSC 21 resolves key questions around the recoverability of remediation costs where the developer no longer owns the property and has no enforceable legal liability to leaseholders at the time of the works.

The Court affirmed that, under English law, a professional consultant may owe a duty of care in tort to a developer client, even where that client has divested its interest in the property and is not subject to a third-party claim. It rejected arguments that BDW’s remediation works were voluntarily incurred and therefore not recoverable.

The ruling will be of significant interest to consultants, developers, insurers, lenders and those operating in the construction sector more broadly. For developers, the case highlights that reputational risk, potential personal injury liability and wider safety obligations may justify remediation, even without third-party claims or ownership. For purchasers and real estate investors, it underscores the importance of factoring latent defect risks into due diligence, as sale or transfer does not necessarily shield against tortious liability.

Background

BDW Trading Ltd (BDW), a major UK developer, engaged URS Corporation Ltd (URS) to provide structural engineering designs for two high-rise residential developments. Following safety reviews in 2019, serious structural defects were discovered. Although BDW no longer owned the properties, it carried out extensive remedial works and brought a negligence claim against URS to recover the costs.

At the time of the works, potential claims by leaseholders under the Defective Premises Act 1972 (DPA) appeared time-barred under the standard six-year limitation period. The Building Safety Act 2022 (BSA), which came into force later, retrospectively extended this period to 30 years, reviving interest in previously time-barred potential claims.

Ground 1: Was BDW’s Remediation “Voluntary” and Irrecoverable?

As BDW had no enforceable liability to leaseholders under the DPA at the time of the works, URS argued that BDW’s losses were voluntarily incurred and therefore outside the scope of URS’ duty of care.

The Court disagreed. It held that while BDW’s DPA liability was time-barred, it remained a continuing legal obligation. BDW still faced potential personal injury claims, which were not time-barred, as well as significant reputational and moral pressure to act. The Court found that BDW had no realistic alternative but to undertake the remediation.

The costs were foreseeable, reasonable and within the scope of URS’ duty of care. This finding is especially relevant for consultants (and their insurers); even where contractual limitation periods have passed, tortious duties may survive, particularly where public safety is at issue.

Ground 2: Relevance of Section 135 of the BSA

The Court confirmed that section 135 of the BSA, which retrospectively extends the limitation period under the DPA to 30 years, was relevant even though BDW’s claim was brought in tort and for contribution, rather than directly under the DPA.

Section 135 applies where the potential for the enforcement of DPA liability forms part of the legal reasoning for another claim, for example, to rebut an argument that remediation was voluntary or that there was no liability for the same damage in a contribution claim context. As a result, BDW’s DPA liability was revived, and there was no limitation bar in place when the costs were incurred.

The Court clarified that section 135 does not preclude a trial judge from considering whether the remedial works were reasonable as a matter of causation or mitigation.

For professionals, the retrospective effect of the BSA significantly increases the exposure window, particularly in tort and contribution claims revived by the (now) longer limitation period under the DPA.

Ground 3: Are Developers Owed Duties Under the DPA?

The Court confirmed that a developer like BDW can be owed a duty under section 1 of the DPA by professionals such as URS. The duty is owed to any person, including a developer, to whose “order” the dwelling is being built.

URS argued that the DPA intended to protect consumers, like individual purchasers, not commercial developers. They also argued that it was anomalous for a developer to owe and be owed the same duty. The Court rejected both arguments.

The Court held that consumer protection would be better served by a broad interpretation of the duty. If a purchaser were to bring a DPA claim against a developer for defective work, and the developer had commissioned that work from a third party, it would be entirely appropriate for the developer to be owed a corresponding duty by that third party. This would ensure the developer could seek redress from the party which had caused the defect and that purchasers would not be left without recourse, particularly in the event of a developer’s insolvency.

The Court dismissed the suggestion that a party cannot owe and be owed the same duty. There is no logical inconsistency as duties under the DPA can run through the chain of responsibility without being circular.

Ground 4: Can a Contribution Claim Arise Without a Third-Party Claim?

The Court held that BDW did not need to be sued by leaseholders in order to claim contribution from URS under the Civil Liability (Contribution) Act 1978.

It was sufficient that BDW:

Faced potential liability for the same damage; and

Had made a payment in kind by undertaking the remedial works as compensation.

Thus, a contribution claim may arise from proactive remediation, taken to mitigate foreseeable liability, without waiting for third-party proceedings. For developers, this decision supports early resolution of defects and may open recovery routes even before formal claims materialise.

Conclusion

With the BSA marking a decisive policy shift towards stronger accountability, this decision confirms that developers who act responsibly to address serious defects can expect greater support from the courts. Significantly, liability for unsafe work can survive divestment and time-bars and cannot easily be avoided by pointing to the absence of formal claims. Construction professionals should expect increased scrutiny of historic projects and prepare for a risk environment where legal responsibility can persist long after practical completion, especially where safety is concerned.

FCA Consults on Proposals for Stablecoin Issuance and Cryptoasset Custody

The UK Financial Conduct Authority (the FCA) recently published two consultations: CP25/14 on stablecoin issuance and cryptoasset custody (CP25/14), and CP25/15 on prudential requirements for cryptoasset firms (CP25/15, and together with CP25/14, the Consultations).

The Consultations are the latest milestone in the FCA’s roadmap for cryptoasset regulation. They build on HM Treasury’s draft legislation published in April 2025, which will bring certain cryptoasset-related activities within the UK regulatory perimeter. Further details on the draft legislation can be found in our previous update (available here).

Scope of the Consultations

The Consultations focus on “qualifying” stablecoins (i.e., cryptoassets that aim to maintain a stable value by referencing at least 1 fiat currency) and related activities. Issuing such stablecoins and custody of qualifying cryptoassets will become regulated activities requiring FCA authorisation when conducted by way of business in the UK.

CP 25/14

In CP 25/14, the FCA seeks views on its proposed rules and guidance for the activities of issuing a qualifying stablecoin and safeguarding qualifying cryptoassets. The proposals aim to ensure regulated stablecoins maintain their value and require customers to be provided with clear information on how the assets backing an issuance of qualifying stablecoins are managed.

Among other things, CP25/14 covers the following proposals:

Authorisation. Firms carrying out the new regulated activities must be authorised under Part 4A of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000;

Full Reserve Backing. Stablecoin issuers must fully back their tokens with high-quality, low risk, liquid assets equal in value to all outstanding stablecoins. These backing assets must be held in a statutory trust and managed by a separate, independent custodian. Reserves are limited to low-risk instruments with only limited use of longer-term public debt or certain money-market funds;

Redemption rights and transparency obligation. Stablecoin holders must have the legal right to redeem qualifying stablecoins at par value on demand directly. The payment order of redeemed funds must be placed by the end of the business day following receipt of a valid redemption request; and

No interest to holders. Firms cannot pass through to stablecoin holders any interest earned on the reserve assets.

CP 25/15

In CP 25/15, the FCA seeks views on its proposed prudential rules and guidance for firms issuing qualifying stablecoins and safeguarding qualifying cryptoassets, including financial resource requirements.

Parts of the proposed prudential regime will be placed in a new proposed integrated prudential sourcebook (COREPRU), while sector-specific prudential requirements for firms undertaking regulated cryptoassets activities will be set out in a new CRYPTOPRU sourcebook.

Notably, the key proposals in CP 25/15 cover the following areas:

Capital requirements. The FCA proposes a minimum own-funds requirement for so-called “CRYPTOPRU Firms” that will require them to hold as own funds the higher of:

a permanent minimum requirement (i.e., £350,000 for issuing qualifying stablecoins or £150,000 for safeguarding of qualifying cryptoassets);

a fixed overhead requirement based on annual expenditure; or

a variable activity-based “K-factor” requirement.

Liquidity requirements. Firms must hold a minimum amount of liquid assets. There will be a basic liquid assets requirement for all CRYPTOPRU firms, and an issuer liquid asset requirement for those that issue qualifying stablecoins.

Concentration risk. Firms will be required to monitor and control for concentration risk, to ensure that they are not overly exposed to one or more counterparties or asset types.

Next Steps

The Consultations close on 31 July 2025. The FCA will consider any feedback before publishing its final rules, which are expected in 2026.

CP 25/14 and CP25/15 are available here and here, respectively.

Leander Rodricks, trainee in the Financial Markets and Funds practice, contributed to this article.

USCIS Makes Changes to TN Policy Manual: Key Updates for Employers

USCIS has released an update to its Policy Manual, bringing significant changes to regulations on the TN nonimmigrant visa classification and perhaps some employers’ practices. For instance, because of changes to the Scientific Technician/Technologist category, employers in the healthcare industry may need to consider other visas for certain roles.

Eligibility

To be eligible for a TN visa, the individual must have Canadian or Mexican citizenship, an offer of employment in a designated USMCA profession, and the qualifications of the profession as specified in the treaty.

The policy update provides:

The intended employment must be with a “U.S. employer or entity” — which appears to be a departure from prior rules. It is unclear whether the policy intends to limit TN employment to an actual U.S. organization and to exclude a foreign employer operating or doing business in the U.S.

Self-employment does not qualify for the TN classification.

Application Procedures

The updated policy appears to expand TN visa application submission to any Class A port-of-entry, which would include both the Northern and Southern borders, and any airport with a CBP post accepting international flights. It also appears to restrict applications at CBP pre-clearance or pre-flight stations to those located within Canada.

Documentation Requirements

The policy update provides:

If the specified profession requires a bachelor’s degree, the applicant must have a bachelor’s degree or the academic foreign equivalent.

If the degree was earned outside of the U.S., Canada, or Mexico, an academic equivalency evaluation is required.

If the profession allows or requires experience in addition to the degree or alternate to the degree, letters from prior employers confirming experience should be provided.

The applicant must meet any licensing requirements that apply to their profession in the state where they will work if they will engage in activities that legally require a license.

Specific Professions

The list of qualifying TN professions includes 63 distinct professional categories. The 2025 policy update changes some individual professions directly:

The Scientific Technician/Technologist (ST/T) must work in direct support of a supervisory professional in one of 10 disciplines. The ST/T category is not applicable for individuals who will work in patient care, as medicine is not a covered discipline.

The Physician may only engage in patient care that is incidental to teaching or research.

The Computer Systems Analyst category does not include programmers, although some incidental programming activities may be performed.

The Economist category does not include market research analysts, marketing specialists, or financial analysts.

Engineers must have a qualifying engineering degree in a field related to the engineering job being offered. The Engineer category should not be used to fill a primarily computer-related position unless the applicant’s background is truly in engineering and the category does not cover generic programmer or technician roles.

Implications

Duration of stay and renewal policies are largely consistent with prior USCIS guidance.

Employers with TN employees will face new challenges under the 2025 update:

Applicants under the Engineers category with degrees unrelated to the job (even if they work in an engineering firm) could face denial. Companies in the tech sector need to ensure the Engineer category is not used for roles like software developer and IT analyst if the individual is not truly an engineer by training.

Mexican and Canadian professionals in finance or marketing roles will find it harder to obtain TNs unless their job description is squarely within economic analysis.

Employers must ensure TN professionals work strictly within the scope of approved employment parameters.

Defra Calls for Comments on Indicative Lists for LC-PFCAs, Their Salts, and Related Compounds

On June 2, 2025, the United Kingdom (UK) Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (Defra) requested comment on a draft indicative list for long-chain perfluorocarboxylic acids (LC-PFCA), their salts, and related compounds. According to Defra, at the 20th meeting of the Persistent Organic Pollutants (POP) Review Committee of the Stockholm Convention on POPs, the Committee recommended listing LC-PFCAs, their salts, and related compounds in Annex A of the Convention, allowing for specific exemptions. Defra notes that the listing extends to compounds classified as substances capable of degrading or transforming into LC-PFCAs. Because of the complexity of identifying and effectively communicating the wide variety of substances that can break down or convert into perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) or LC-PFCAs, the Committee established an intersessional working group to develop a draft indicative list of long-chain PFCAs, their salts, and related compounds. Defra states that the draft indicative list for LC-PFCAs will complement existing registers, covering the listings of PFOA, its salts, and PFOA-related compounds, as well as perfluorohexanesulfonic acid (PFHxS), its salts, and PFHxS-related compounds. The Committee seeks additional information and feedback on the indicative lists. Comments are due June 30, 2025.

Council of the EU and EP Agree on “One Substance, One Assessment” Legislative Package

The Council of the European Union (EU) announced on June 12, 2025, that it reached a provisional agreement with the European Parliament (EP) on the “one substance, one assessment” (OSOA) legislative package, “which aims to streamline assessments of chemicals across relevant EU legislation, strengthen the knowledge base on chemicals, and ensure early detection and action on emerging chemical risks.” The package contains three proposals: a directive concerning the re-attribution of scientific and technical tasks; a regulation aimed at enhancing cooperation among EU agencies in the area of chemicals; and a regulation establishing a common data platform on chemicals. According to the Council, the co-legislators maintain the objectives of the European Commission’s (EC) legislative package but expanded the information available in the common platform to include scientific data submitted voluntarily, clarified the treatment of medical data, and ensured that the content of the platform will be publicly available. The provisional agreement will now be considered by the Council of the EU and the EP for formal adoption.

According to the press release, the OSOA package would create a common platform to integrate existing databases and provide a “one-stop shop” for chemical data from EU agencies and the EC. The platform would allow one legislative area to share knowledge with another and would mandate the systematic collection of human biomonitoring data to inform policymakers about chemical exposure levels. The press release notes that a monitoring and outlook framework “will detect chemical risks early, support fast regulatory responses, and track impacts through an early warning system and indicators.” It would also empower the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) to generate data when needed and ensure transparency of scientific studies.

Under the agreement, the platform, hosted by ECHA, would provide access to all chemical data generated or submitted as part of the implementation of “about” 70 pieces of EU legislation. The agreement requires ECHA to create and manage a database, inside the common data platform, that lists alternatives to substances of concern. The database should include alternative technologies and materials that do not require such substances of concern. The agreement specifically supports the voluntary submission of scientific data to be included in the platform.

The press release states that the agreement considers that certain categories of newly generated data relating to chemical substances present in medicinal products from the European Medicines Agency (EMA) must also be addressed. According to the press release, the EC will assess whether to add further categories of chemical data related to medicinal products (for instance, other elements than active substances, substances that are now considered non-relevant, or data held by national agencies) in the future. The press release notes that the co-legislators agreed that legacy data from EMA (i.e., data generated and submitted before the entry into force of the regulation) would be gradually integrated into the platform, starting six years after the regulation enters into force.

Under the agreement, the platform would provide access to data that are already public, in line with the rules of the originating legal acts. The press release notes that the OSOA package will help ECHA, and other agencies, to generate studies for multiple purposes. The agreement proposes that four years after the regulation on the common data platform enters into force, ECHA should commission an EU-wide human biomonitoring study to understand better the population’s exposure to chemicals. Human biomonitoring data from the EU and national research programs will also be included in the platform.

Commentary

OSOA is part of the 2020 Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability (the CSS), a key building block of the European Green Deal. As a core element of the European Green Deal’s zero pollution ambition, the CSS aims to strengthen protection for people and the environment while driving innovation toward safer and more sustainable chemicals. One of the goals of the CSS is to simplify and consolidate the EU regulatory framework on chemicals, and OSOA is intended to establish a simpler process for assessing chemical risks and hazards.

UK regulator has fake reviews in its sights

The Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act 2024 (DMCCA) [Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act 2024] has both increased consumer protection rights in the UK and the enforcement powers of the main consumer regulator, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) which for the first time has been granted wide-ranging powers to investigate suspected breaches of consumer law and unilaterally impose significant fines. Prior to the DMCCA the CMA had to go via the courts for a business to face fines, a power that was exercised infrequently [A New Era for Consumer Law and Regulation | Global IP & Technology Law Blog].

One of the many areas in which the DMCCA has increased and clarified consumer protection rights are fake reviews and reviews which conceal the fact that they have been provided in return for an incentive (whether monetary or otherwise) (banned reviews). The new rules apply to banned reviews however those are made available, whether online or otherwise.

In particular, the DMCCA has introduced specific new offences of submitting or commissioning a banned review, offering to procure a banned review and offering services that facilitate the submission, commission or publication of a banned review.

However, for legitimate traders who display or make available consumer reviews in any media (classified under the DMCCA as a “publisher”) one of the biggest changes is a new positive obligation to take effective action to prevent banned reviews appearing. That obligation includes requirements to: (1) have a clear policy on the prevention and removal of banned reviews; and (2) assess the risk of banned reviews appearing and take such further proactive steps as are “reasonable and proportionate” to address any risks that are identified.

In April the CMA published statutory guidance on the sort of measures which it expects publishers to have in place. That guidance makes clear that the CMA does not consider there to be a ’one size fits all’ or ’tick box’ approach that is appropriate for all publishers. As such, the regulator accepts that what is appropriate for one publisher might not be right for another [CMA208 – Fake reviews guidance]

Since publishing this guidance, the CMA has moved into enforcement territory -initially focused on the big players in the consumer review market. Indeed, earlier this year, the CMA secured undertakings from Google, including an agreement to sanction UK businesses that boost their star ratings with fake reviews as well as sanctioning people who have written fake reviews for UK businesses [CMA secures important changes from Google to tackle fake reviews – GOV.UK] and more recently formal undertakings have been secured from other high-profile brands to enhance existing systems for tackling fake reviews.

However, the CMA is not stopping there and on 6 June announced that in its next phase of work to tackle fake reviews it will be looking into the conduct of other players across the sector to determine whether further action is required [Online reviews – GOV.UK]. As part of this phase, the CMA is currently conducting an initial sweep of review platforms to identify those who need to do more to comply with these new requirements. As such, it is likely that many websites which publish consumer reviews but have not yet taken steps to comply with these new requirements will face enforcement action by the CMA if they fail to rectify that.

DOJ Releases Promised Guidelines for Investigation and Enforcement Under the FCPA

On Monday June 9, 2025, the Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche released “Guidelines for Investigations and Enforcement of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.” This much anticipated update directly responds to Executive Order 14209, signed by President Trump earlier this year, which temporarily paused Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) enforcement. The new Guidelines focus FCPA enforcement going forward on protecting U.S. business interests, furthering the Administration’s efforts to stamp out cartels and transnational criminal organizations, and prioritizing prosecution of individuals rather than corporations. Conduct that can be described as “routine business practices” in foreign countries, under the Guidelines, will not be pursued.

The Guidelines reference and closely mirror Executive Order 14209 (EO) which stated that the FCPA should not be “stretched beyond proper bounds and abused in a manner that harms the interests of the United States,” or enforced in a manner that “harms American economic competitiveness and, therefore, national security.” EO, § 1. The EO reflected the Administration’s concern that FCPA enforcement created a competitive disadvantage abroad and instructed the Department of Justice (DOJ) to stop all new FCPA proceedings for 180 days, review ongoing FCPA matters to ensure alignment with U.S. interests, and issue updated guidelines for investigation and enforcement.

Now that the Guidelines have been issued, it is clear the DOJ will continue to enforce the FCPA but with more focus on industries that touch on the Administration’s foreign policy goals (like defense, critical infrastructure, and strategic resources) and foreign companies competing with U.S. companies.

The New Approach Set Forth in the Guidelines

1. Approval to Initiate FCPA Cases

The Guidelines require that all new FCPA cases must be authorized by the Assistant Attorney General for the Criminal Division, or a more senior official. This new approval process means that top DOJ leadership will be keeping a watchful eye on line prosecutors to ensure adherence to the priorities described in the Guidelines.

2. The Principal Factors in Prosecution Decisions

The Guidelines set out four factors for prosecutors to consider when deciding whether to investigate or prosecute a potential FCPA violation. The Guidelines repeatedly state that these factors are not exhaustive and “myriad factors must be considered when determining whether to investigate or prosecute.” It is clear, however, that these four substantive issues will undoubtedly receive significant attention in charging decisions and resolutions. All existing FCPA actions will be reviewed under these parameters within the next 180 days, and all future actions will be governed by these Guidelines.

a. Combating Cartels and Transnational Criminal Organizations

A primary consideration in deciding whether to pursue an FCPA action under the new Guidelines is whether the alleged conduct is linked to a cartel or transnational criminal organization.

b. Protecting U.S. Business Opportunities

Prosecutors are now directed to target conduct that “deprived specific and identifiable U.S. entities of fair access to compete” or resulted in economic harm to U.S. companies or individuals. This may prompt U.S. based companies to report potential FCPA violations in situations, for an example, when a foreign competitor secures a contract from a foreign government in a bidding process.

c. National Security Considerations

The third factor prosecutors are to consider under the Guidelines is whether the alleged misconduct undermines U.S. national security by preventing the U.S. or American companies from accessing strategic business sectors. The Guidelines reference the EO’s focus on “critical minerals, deep-water ports, or other key infrastructure or assets.” The clear goal is to use the FCPA to prevent threats to national security caused by bribing corrupt foreign officials in these key strategic sectors.

d. “Serious Misconduct”

The Guidelines discourage – and likely will entirely stop the investigation of any routine, business practices and minor gifts or hospitality. Instead, the DOJ will focus on major bribery schemes, evidence of concealment or obstruction, and cases with strong indicia of corrupt intent tied to specific individuals. The Guidelines also leave room for prosecutors to make enforcement decisions based on the likelihood (or lack thereof) of foreign law enforcement actions.

What Happens Next?

The FCPA Guidelines are just one of the many changes to the Administration’s policies on investigation and enforcement of white collar crime. Matthew Galeotti, head of the Justice Department’s Criminal Division, said at an anti-corruption conference in New York on Tuesday “the through-line is that these Guidelines require the vindication of U.S. interests.”

This means that companies should consider reassessing their risk in the areas now prioritized by the DOJ, especially when doing business in regions with significant cartel activity, and transactions related to strategic business sectors. Companies should update compliance programs to ensure they are tailored to address the specific factors identified in the Guidelines and in line with global anti-bribery laws. Additionally, companies should be cognizant of the focus on individual accountability when conducting internal investigations and shape compliance programs to identify culpable individuals and take appropriate action.

Companies should also be aware that these Guidelines are just that, guidelines. They create no enforceable rights, and the FCPA is still the law of the land and has a minimum five-year statute of limitations. Maintaining a compliance program that complies with the FCPA to its fullest extent remains as vital as ever.

How President Trump’s ‘One Big Beautiful Bill’ Will Impact Businesses in Australia

Retaliatory tax provisions contained in H.R. 1, the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” that recently passed the US House of Representatives, if enacted, would drastically impact common cross-border transactions, including US operations of foreign multi-national groups and inbound investments.

APPLICABILITY OF SECTION 899

Code Section 899 imposes retaliatory taxes on “applicable persons” resident in “discriminatory foreign countries,” which are defined as countries that impose unfair foreign taxes (UFTs). The US Treasury Department would quarterly publish a list of discriminatory foreign countries. The “applicable persons” subject to increased taxes include individuals and corporations resident in discriminatory foreign countries, as well as foreign corporations more than 50% (by vote or value) owned directly or indirectly by such applicable persons (unless such majority-owned corporations are publicly held). Subsidiaries of US-parented multinational groups would generally not be applicable persons.

Three categories of taxes are identified as “per se” UFTs: undertaxed profits rule taxes imposed pursuant to the OECD’s Pillar 2, digital service taxes, and diverted profits taxes.

Australia has adopted both the Undertaxed Profits Rule as well as the Diverted Profits Tax, and so Australia is a discriminatory foreign country and subject to the retaliatory tax provisions in section 899.

Certain categories of taxes, including value-added taxes, goods & services taxes, and sales taxes, are exempted from being classified as UFTs. Australia’s Digital Services Tax is contained in the Goods and Services Tax and so is not currently classified as having a Digital Services Tax.

When a country repeals all of its UFTs, it generally will cease to be a discriminatory foreign country, and persons associated with that country generally will cease to be applicable persons.

RETALIATORY TAX PROVISIONS

The retaliatory tax provisions in Code Section 899 mainly fall into two categories, (1) increased rates of US tax on applicable persons, and (2) a more stringent version of the base erosion and anti-abuse tax (“BEAT”) currently contained in Code Section 59A, referred to as the “Super BEAT.”

Increased Rates of US Tax on Applicable Persons

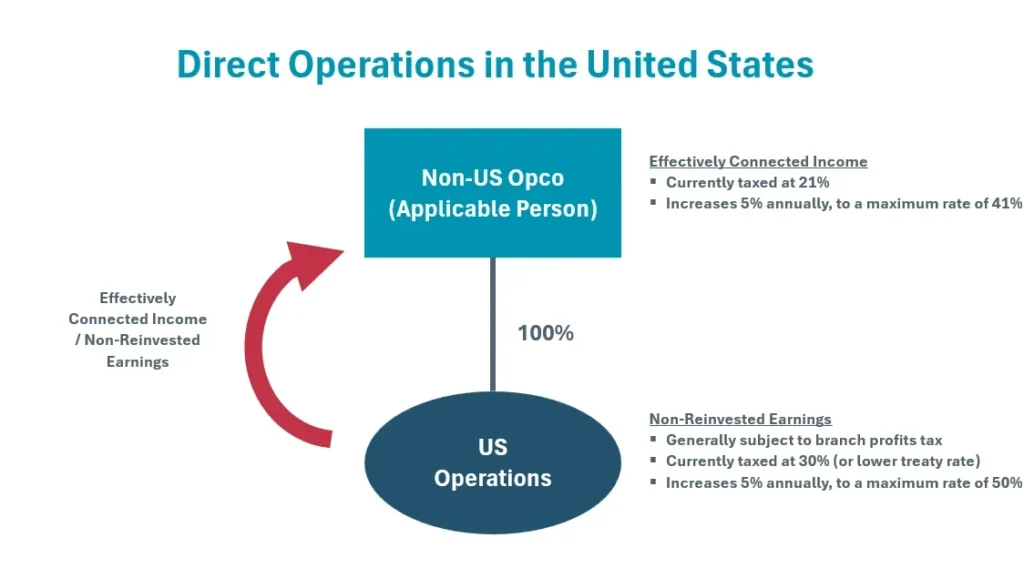

The rates of US tax to which applicable persons are subject would be increased 5 percentage points each year, possibly beginning in the current year, until the rates reach a maximum of 20 percentage points above the current statutory rates (determined without regard to any treaty). The applicable US tax rates that would be subject to increase include (1) the 30% withholding tax on passive US-source income (e.g., dividends, interest, rent, and royalties), (2) the 21% corporate income tax, and (3) the 30% branch profits tax imposed on the non-reinvested earnings of a US trade or business conducted by a foreign corporation.

Income that is currently statutorily exempt from US tax–such as US-source interest income that qualifies for the “portfolio interest” exemption–would, generally speaking, remain exempt from US tax; however, Code Section 899 expressly overrides the US tax exemption for sovereign wealth funds and other foreign governmental entities contained in Code Section 892.

In the case of appliable persons that qualify for a zero or reduced rate of tax pursuant to an income tax treaty, the increased tax rate to which the applicable person is subject would initially be 5 percentage points above the applicable treaty rate, although the rate would climb 5 percentage points each year until it reached 20 percentage points above the maximum statutory rate (determined without regard to a treaty). This may result in a 50% withholding rate on certain distributions from the United States.

The Super BEAT

In addition to the current BEAT in Code Section 59A, which was adopted as part of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, Code Section 899 would impose a modified “Super BEAT” on US corporations which are more than 50% owned (by vote or value, directly or indirectly) by applicable persons.

Several aspects of the Super BEAT would make it more likely for targeted companies to be liable for the BEAT. First, certain thresholds that limit the applicability of the regular BEAT would be removed. The current BEAT only applies to US subsidiaries (1) of multinational groups with gross receipts of at least $500 million, and (2) whose “base erosion” payments – i.e., deductible payments to related foreign persons–exceed 3% of total deductions (or 2% in the case of certain financial firms). These thresholds would not apply under the Super BEAT, potentially subjecting US companies to the Super BEAT despite not being part of large multi-national groups or making significant related-party payments.

The new Super BEAT would potentially both increase the tax liability of current BEAT taxpayers and subject additional US companies to the BEAT.

APPLICATION TO COMMON CROSS-BORDER TRANSACTIONS

CONCLUSION

The retaliatory tax provisions in Code Section 899, if enacted, would have a significant and potentially negative impact on a wide variety of cross-border transactions, including US operations of foreign multi-national groups. Click here for a more comprehensive alert on this issue.

New Proposed Dutch Self-Employment Legislation

On 3 April, a new legislative proposal by the political parties VVD, D66, CDA and SGP was published for consultation. It aims to bring long-awaited clarity to the legal status of self-employed individuals in the Netherlands. It partially replaces a previous proposal by the Dutch government (Wet verduidelijking beoordeling arbeidsrelaties en rechtsvermoeden; WVBAR) which addresses similar issues but had been subject to criticism from some stakeholders, including the Dutch Council of State. The political parties submitting the new legislative proposal believe it provides for a clearer framework than the WVBAR for determining the legal status of a working relationship.

Like many other countries, The Netherlands has long struggled with the grey area between employment and self-employment. Recent rulings from the Dutch Supreme Court emphasize that the key criteria for classifying employment relationships — including the distinction between employees and the self-employed – remain primarily a legislative matter. Indeed, issues such as whether to further define what it means to be “in service of” someone, how deeply the work is embedded within an organization, or whether to introduce legal presumptions (for example, based on remuneration levels) are all currently being considered by both Dutch and European lawmakers. The Supreme Court made it clear that no further judicial developments in this area are appropriate at this time, signaling a clear need for legislative action rather than court rulings to clarify and regulate these matters.

Self-Employment Law (Zelfstandigenwet)

This latest legislative proposal is designed to address long-standing challenges in the Dutch labor market by pursuing three core objectives. First, it aims to provide legal certainty for both self-employed individuals and the businesses that engage them, offering clarity around the classification of work relationships. Second, it seeks to modernise labour legislation to better reflect today’s labor market, acknowledging the growing desire among many professionals to work independently and retain greater autonomy. Third, it strives to create a level playing field between employees and the self-employed, while simultaneously enhancing the social protection available to the latter.

To achieve these goals, the legislative proposal introduces a three-stage cumulative assessment to determine whether someone may lawfully operate as a self-employed individual.

1. Independence test

The independence test consists of five mandatory criteria. An individual will only be considered as self-employed if they meet all the following conditions:

They work for their own account and at their own risk;

They maintain proper and reliable administration (i.e. accounts and the other records appropriate to a free-standing business);

They present themselves in the market as an independent entrepreneur;

They have made adequate arrangements to protect against the risk of incapacity for work; and

They contribute proportionately to a provision that protects against income loss and/or risk of poverty in retirement.

It would be the responsibility of the self-employed individual to demonstrate that they comply with these criteria.

2. Working relationship test

If the individual satisfies the first test, the next stage is to assess whether the working relationship between the parties qualifies as self-employment – the relationship must meet all four of the following criteria:

There is a mutual intention between the parties to collaborate outside the context of an employment contract;

The self-employed individual has freedom to determine their own working hours;

The self-employed individual has freedom to organise their own work; and

There is no hierarchical supervision exercised by the client over the individual.

The written agreement between the parties must explicitly explain how these criteria are fulfilled.

3. Sectoral legal presumption

Finally, in those sectors with a high risk of false self-employment, the new proposal allows for sector-specific legal presumptions. These presumptions help establish when a relationship is likely to be an employment contract rather than genuine self-employment, based on factors tailored to the particular industry. This approach balances the need for sector-specific enforcement in areas vulnerable to abuse, while avoiding unnecessary regulation in sectors where genuine self-employment is more common and less problematic.

New Supervisory Body

The proposal also seeks to establish a Commission for the Assessment of Self-Employed Persons (Commissie Beoordeling Toetsingskader Zelfstandigenwet). This body would be able to provide legally binding advice to one or both parties and evaluate the working relationship either before, or within a year of, the contract starting. It would play a vital role in providing early and binding clarity, reducing uncertainty and disputes about employment status.

Impact

Under this latest proposal, businesses would take greater responsibility for classifying correctly the status of individuals working for them. It offers reduced legal risk thanks to the clearer frameworks, but it also requires companies to stop relying on outdated model agreements and instead assess each contract individually. For genuinely self-employed individuals, the proposal provides clearer recognition of their entrepreneurial status and mandates protections against income loss and pension gaps. Overall, it should pave the way for greater legal certainty for all parties when entering contracts.

The legislative proposal is currently open for consultation until 23 June 2025, allowing stakeholders and the public to review and provide feedback on the draft law. However, following the collapse of the Dutch government on 3 June – after the PVV withdrew from the governing coalition – new elections will be held on 29 October. As a result, the future of many recent legislative proposals, including this one, remains uncertain. We will of course keep you posted on developments.

France’s Nuclear Gamble: Status, Challenges and the Road Ahead

France is doubling down on nuclear energy. Once a symbol of national pride and now the backbone of its decarbonized electricity mix, nuclear power is experiencing a full-fledged renaissance in France. After years of hesitation, political consensus has crystalized around a clear ambition: to make nuclear energy the cornerstone of both climate neutrality and energy sovereignty.

With nearly 70 percent of its electricity still coming from nuclear sources, France stands out globally for its unique energy mix. While other nations have sought to phase out or limit their nuclear capacity, France is investing heavily in its expansion, most notably through the planned construction of 14 next-generation EPR2 reactors and a growing focus on innovative technologies like Small Modular Reactors (SMRs).

This renewed momentum is backed by a supportive legislative and regulatory framework, with reforms aimed at streamlining procedures without compromising safety. However, the scale of the challenge is significant. The sector faces persistent industrial, financial and social headwinds. Whether France can overcome these hurdles will determine not only the success of its nuclear revival but also the future shape of its energy mix as it pursues carbon neutrality by 2050.

A Historic Choice That Still Shapes Today’s Energy Mix

France’s reliance on nuclear power is rooted in a bold political decision made in response to the 1974 oil crisis, known as the “Messmer Plan.” Today, nuclear power still accounts for more than two-thirds of French electricity production. In 2024, 67.1 percent of French electricity came from nuclear plants, with 57 reactors operating across 18 sites.[1]

With a total nuclear capacity of 62.9 GWe, France is the second-largest producer of nuclear electricity globally. This longstanding commitment to nuclear energy has allowed the country to maintain one of the lowest carbon electricity mixes in Europe.

While nuclear energy has sparked public debate, especially on safety and environmental issues, political support has shifted firmly back in its favor. Plans to reduce the nuclear share to 50 percent were first delayed and then abandoned entirely in 2022, in recognition of the energy transition and security challenges ahead.

A State-Led Ecosystem of Strategic Players

France’s nuclear industry is structured around a tightly coordinated group of state-backed entities:

Electricité de France (EDF), fully state-owned, operates all nuclear reactors.

Orano, 90 percent state-owned, manages the entire nuclear fuel cycle, from uranium mining to spent fuel.

ANDRA handles radioactive waste and oversees the controversial Cigéo deep geological repository project in Bure.

The Commission for Atomic Energy and Alternative Energies (Commissariat à l’Énergie Atomique et aux Énergies Alternatives) conducts cutting-edge nuclear and energy R&D.

The Nuclear Safety Authority (Autorité de sûreté nucléaire or ASN) and the Radiation Protection Institute (Institut de radioprotection et de sûreté du nucélaire) ensure oversight, transparency, and safety.

Framatome, 80 percent owned by EDF, designs and manufactures nuclear reactors and components.

Together, these institutions manage each stage of the nuclear cycle, from generation to disposal, ensuring full lifecycle control and a high degree of safety and public accountability.

The State of the Nuclear Fleet: Aging Infrastructure and the Need for Renewal

France’s nuclear fleet is standardized around Pressurized Water Reactors (PWRs), including 56 second-generation units and one third-generation European Pressurized Reactor (EPR), which is a specific, advanced design that evolved from the PWR technology, at Flamanville, commissioned in December 2024. It was the first new reactor since 1999.

The long gap between new projects resulted from several factors: a temporary overcapacity, a policy shift favoring renewables, and massive delays and cost overruns in existing projects. For example, the Flamanville EPR ended up costing over €23 billion, compared to the initial estimate of €3.3 billion.

Reactors were originally designed for 40 years of operation (60 years for EPRs), but extensions beyond this period are possible with ASN approval. The average age of the current fleet is 39 years, and the oldest still-operating reactors date back to 1979. Coordinating the decommissioning of these older units with the launch of new ones is now a critical challenge. The premature closure of Fessenheim, intended to coincide with Flamanville’s start-up, failed to achieve this synchronization.

A Renewed Legal and Regulatory Framework

France’s nuclear regulation was consolidated in 2006 with the Transparency and Nuclear Safety Act (TSN),[2] which created the ASN and set out new obligations on transparency, public information, and environmental protection. This framework was further updated in 2016 to align with EU law through the transposition of three key Euratom directives on nuclear safety, radiation protection, and waste management.

More recently, the 2023 Nuclear Acceleration Act[3] simplified permitting procedures to speed up the construction of new reactors. Key reforms include the separation of nuclear permits from land development approvals, streamlined environmental assessments and shorter litigation timelines. Meanwhile, the EU’s inclusion of nuclear energy in its green taxonomy in 2022 confirmed its status as a sustainable energy source, subject to stringent safety and waste management criteria.

A New Economic Model for Nuclear Power

For over a decade, France operated under a unique regulatory scheme known as ARENH (Regulated Access to Historic Nuclear Electricity), introduced in 2010 to open the electricity market to competition. Under this system, EDF – France’s state-owned utility – was required to sell a portion of its nuclear output (up to 100 TWh per year) at a fixed low price (€42/MWh) to alternative suppliers.

While initially intended to foster competition and benefit consumers, the mechanism became increasingly unsustainable for EDF, especially during periods of high market prices, such as the 2022-2023 energy crisis. It also drew growing criticism from the European Commission, which considered it a distortion of competition and incompatible with EU internal market rules. In response, the French government decided to phase out ARENH by the end of 2025.The phase-out of the ARENH mechanism marks a turning point in the sector’s financial regulation. From 2026 onward, EDF will operate under a new regime based on revenue-sharing and consumer protection.

This post-ARENH model introduces:

A tax on excess nuclear revenues, with a 50 percent levy above a set threshold and up to 90 percent above a higher “capping” threshold.

A universal nuclear rebate, funded by this tax, to reduce electricity bills for all consumers.

An oversight from the Energy Regulation Commission, France’s independent regulatory authority overseeing the electricity and gas markets, ensuring that the system remains transparent and effective.

The new framework is designed to ensure EDF’s financial stability, attract investment, and maintain competitive energy prices for end users.

Industrial Revival and Strategic Investment

France’s nuclear renaissance is anchored in two main projects: the construction of six EPR2 reactors (with the potential for eight more) and the development of SMRs like the NUWARD project. Delays have already pushed the first EPR2 commissioning from 2035 to 2038, while the estimated cost of the program has risen to nearly €80 billion.

Financing is expected to come from state-backed loans, a regulated CfD model offering EDF a guaranteed price of €100/MWh, and private investments through initiatives like the France Nuclear Fund 2, aimed at supporting SMEs in the supply chain.

These projects are also embedded in the forthcoming Multiannual Energy Program(PPE 3), which will reaffirm nuclear power’s central role while encouraging innovation in reactor design, fuel reprocessing, and fusion research. Notably, the CEA’s WEST tokamak set a world record by maintaining plasma for over 22 minutes, a key step in the pursuit of fusion energy.

France’s Position on the European Stage

France’s pro-nuclear stance also extends to EU negotiations. In April 2025, Paris formally opposed efforts to raise renewable energy targets without parallel recognition of nuclear energy. It advocates replacing the current Renewable Energy Directive with a broader, “decarbonized energy” directive that includes nuclear on equal footing. Germany’s recent shift in stance toward nuclear power, despite its historical opposition and the closure of its last nuclear plants in 2023, marks a significant step toward recognizing nuclear energy as a long-term low-carbon asset. In May 2025, Germany announced that it would no longer oppose French efforts to incorporate nuclear power into European legislation.

This reflects a broader effort to secure regulatory parity for nuclear energy, emphasizing France’s uniquely low-carbon electricity mix. As the EU works toward its 2040 climate goals and prepares its roadmap for COP30, France is positioning itself as a leader in pragmatic, diversified decarbonization.

Conclusion

In conclusion, France’s bet on nuclear energy is bold but calculated. Its success depends on mastering complex industrial projects, securing sustainable financing and maintaining public and political support. If successful, France will not only preserve its unique energy model but may also set the standard for a low-carbon, resilient electricity system in Europe and beyond.

In this context, navigating the legal, financial, and regulatory framework will be critical for investors, suppliers and stakeholders across the nuclear value chain.

This article was co-authored with Bracewell trainees Tala Fawaz and Gwénolé Noyalet.

Read a French language version of this article.

FOOTNOTES

[1] RTE, Bilan Electrique 2024.

[2] Law No. 2006-686 of 13 June 2006 on transparency and safety in nuclear matters.

[3] Law No. 2023-491 of 22 June 2023 on accelerating procedures related to the construction of new nuclear facilities near existing nuclear sites and the operation of existing facilities.