Policyholder Plot Twist – Cyber Insurer Sues Policyholder’s Cyber Pros

When a cyber incident occurs and the insurer pays out the claim, they often face the frustrating reality that pursuing the actual criminals – the threat actors – for indemnification is virtually impossible. Thus, insurers are now turning to subrogation claims against the very cybersecurity vendors entrusted by policyholders to protect their systems. Indeed, insurers are increasingly examining whether outsourced cybersecurity providers may have breached their contractual obligations or failed to deliver adequate protection, leading to the loss. This shift means policyholders may find their cybersecurity vendors facing legal action from their own insurer, creating a new layer of risk in vendor relationships.

Last month, Ace American Insurance Company filed a subrogation action against its insured’s cybersecurity and technology vendors, alleging missteps by the technology companies. See Ace American Insurance Company v. Congruity 360, Trustwave Holdings, Case No. 2:25-cv-15657 (D.N.J. Sep. 15, 2025). Ace seeks to recover the $500,000 in damages it paid to its insured, CoWorx, under the cybersecurity policy issued by Ace. Ace alleges that its insured’s cyber incident occurred as a result of Congruity 360 and Trustwave’s negligence. Ace also asserts breach of contract against both defendants.

The complaint details several alleged bases for Ace’s subrogation action against the technology companies contracted by its insured. Against Congruity 360, Ace claims that the contract between CoWorx and Congruity 360 required Congruity 360 to set up multifactor authentication and secure network servers for CoWorx. Ace further alleges that Congruity 360 failed to do so, leading to installation of ransomware. The claims against Trustwave are similar. Ace alleges that Trustwave failed to properly notify the appropriate parties of the cyber incident, preventing CoWorx from being able to take relevant proactive action and significantly increasing CoWorx’s damages from the incident.

Subrogation actions by cyber insurers are becoming more prevalent and, indeed, we are seeing cyber insurers frequently request vendor contracts from their insureds following a cyber incident so that the insurer can evaluate potential subrogation rights. Insurers are likewise scrutinizing a policyholder’s security controls during policy underwriting, looking for evidence that policyholders are managing vendor risk proactively and contractually, to help set premiums and respective policy language. This underscores that, in today’s cyber insurance landscape, the quality of your vendor contracts can directly impact coverage, claims, and your exposure to third-party litigation.

FCA Starts Consultation on UK Motor Finance Consumer Redress Scheme

On 7 October 2025, the FCA published a consultation paper (the “Consultation”) on an industry-wide scheme to compensate motor finance customers who were treated unfairly between 2007 and 2024 (the “Motor Finance Consumer Redress Scheme”). The FCA has also set out steps and its expectations before finalisation of the Motor Finance Consumer Redress Scheme rules in the Dear CEO letter (“Dear CEO Letter”) that the FCA has sent to lenders and brokers alongside the publication of the Consultation.

Nikhil Rathi, chief executive of the FCA, expects that “there will be a wide range of views on the scheme, its scope, timeframe and how compensation is calculated. On such a complex issue, not everyone will get everything they would like. But we want to work together on the best possible scheme and draw a line under this issue quickly.”

The Consultation aims to balance several principles to deliver an easy-to-access and simple-to-deliver scheme, providing fair compensation promptly while ensuring the continued integrity of the motor finance market.

The Consultation departs from the usual three-month consultation period and will close on 18 November 2025 for comments on the overall design of the Motor Finance Consumer Redress Scheme and on 4 November 2025 for comments on the proposals to further extend how long firms have to provide a final response to certain motor finance complaints. If adopted, the Motor Finance Consumer Redress Scheme will be given effect through amendments to CONRED (the FCA’s Consumer Redress Schemes sourcebook).

Background

On 1 August 2025, the UK Supreme Court handed down its long-awaited judgment in Johnson v FirstRand Bank Ltd, Wrench v FirstRand Bank Ltd, and Hopcraft & Anor v Close Brothers Ltd, reported together as [2025] UKSC 33 (“Hopcraft Decision”). While fiduciary duty and bribery claims were dismissed, the Court upheld an “unfair relationship” under s.140A of the Consumer Credit Act 1974 (“CCA”), an outcome with clear implications where intermediary commission or contractual ties were not properly disclosed. For further information in relation to the judgement, please refer to our article here.

The FCA had signaled since March 2025 that it would consult swiftly to give certainty to firms, investors, and customers, and is now proposing to use its power to set up the Motor Finance Consumer Redress Scheme.

Firms and Vehicles in Scope

Who delivers the scheme? The FCA proposes that lenders will operate the Motor Finance Consumer Redress Scheme, with brokers required to co‑operate and provide information promptly, including remitting complaints received to the lender for determination under the Motor Finance Consumer Redress Scheme.

Where liabilities have been assigned or acquired, the assignee would also be responsible for obligations arising from the Motor Finance Consumer Redress Scheme.

What agreements are covered? The scheme would apply to regulated credit agreements used to buy or hire‑purchase a motor vehicle. These are most likely to be personal contract purchase (PCP), hire purchase (HP), or conditional sale agreements. Consumer hire (leasing) agreements are excluded because section 140A of the CCA does not apply to hire. A “motor vehicle” is defined as a “mechanically propelled vehicle intended or adapted for use on roads to which the public has access”. The FCA does not provide an exhaustive list, but caravans and jet skis are given as examples out of scope.

How does the Consultation describe the Scope?

“Subject matter” defines the conduct issues addressed by the Motor Finance Consumer Redress Scheme, a relationship would be considered unfair where there was inadequate disclosure in connection with a motor finance agreement of one or more of the following:

a discretionary commission arrangement (“DCA”);

high commission (where the commission is equal to or greater than 35% of the total charge for credit and 10% of the total loan amount of credit, the relevant values are as at the start of the agreement); or

contractual ties that gave a lender exclusivity or a right of first refusal.

As DCAs are already defined in the FCA Handbook, the FCA is only seeking views on the proposed definitions of high commission payments and contractual ties.

The 35%/10% threshold is the point at which the FCA’s analysis best indicates that borrowing costs may have been more strongly affected by the commission, such that its size would likely to have been a major consideration in the consumer’s mind had they been aware of it when they took out the loan.

The Consultation makes it clear that these thresholds are solely for the purpose of the design of the Motor Finance Consumer Redress Scheme and should not be read across to any other retail financial services market.

A “scheme case” is an agreement the lender assesses under the Motor Finance Consumer Redress Scheme rules. To be a Motor Finance Consumer Redress Scheme case, there must be a relevant motor finance credit agreement and a commission payable by the lender to the broker; cases already finally resolved via court, the Financial Ombudsman Service (“FOS”), or accepted settlement are excluded.

Time Limitation

The Motor Finance Consumer Redress Scheme would cover regulated motor finance agreements taken out between 6 April 2007 and 1 November 2024 where commission was payable by the lender to the broker. The FCA is proposing that lenders will deliver the scheme, rather than brokers.

The FCA states that the start date aligns with the date on which s.140A of the CCA took effect. The end date is based on when the FCA expected firms to move to more transparent practices following the UK Court of Appeal judgment on 24 October 2024 that was subsequently appealed to the UK Supreme Court.

The Consultation sets out that consumers who have already been compensated for complaints covered by the Motor Finance Consumer Redress Scheme would be excluded. Consumers who have a live complaint with the FOS would have their case resolved by the FOS and not through the Motor Finance Consumer Redress Scheme.

Key Elements of the Motor Finance Consumer Redress Scheme

a. Consumer Consent Model (Opt-in/Opt-out): Customers who already complained to a firm (but not to FOS) are in scope by default unless they opt out, firms must contact these customers within three months of the start of the Motor Finance Consumer Redress Scheme.

All other customers must opt in, meaning firms must contact them within six months of the start of the Motor Finance Consumer Redress Scheme.

Customers who have not been contacted can approach their lender to review their case within one year of the Motor Finance Consumer Redress Scheme start date.

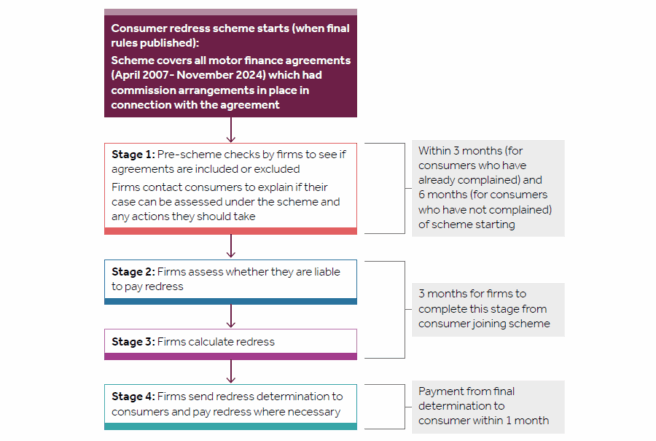

b. Four Stage Process and Timing: The Consultation sets out in four stages the proposed Motor Finance Consumer Redress Scheme and the steps lenders, brokers, and consumers will need to take. Please see below flow chart that provides an overview of the proposed Motor Finance Consumer Redress Scheme stages and timings.

Source: FCA consultation paper CP25/27.

c. Redress Calculation: Recognising the Hopcraft Decision, the FCA proposes that consumers whose cases align closely with the Hopcraft Decision should get the commission repayment remedy.

For most other cases, redress would be calculated using a hybrid approach that averages two methods, the commission repayment remedy and an APR adjustment remedy (which applies a reduced APR to reflect estimated financial loss). This approach aims to balance evidence of consumer loss with the broader range of remedies courts might award, given the uncertainty in cases that differ from the Hopcraft Decision.

In the very limited circumstances where the APR adjustment remedy would produce greater redress than the commission repayment remedy (if relevant) or hybrid remedy (if not), the FCA proposes consumers should get the APR adjustment remedy.

d. Possibility for Rebuttal: The Consultation proposes enabling lenders to rebut the presumption of unfairness in some limited circumstances. For example, lenders would be entitled to determine there was no unfair relationship under the Motor Finance Consumer Redress Scheme if:

there is evidence of adequate disclosure of the relevant arrangement in question; or

in cases only featuring a DCA, the lender can provide evidence that the broker selected the lowest interest rate at which they would not have made any additional commission; or

disclosure of the relevant arrangement in question was inadequate, but the lender can provide evidence that the consumer was sufficiently sophisticated to have nonetheless been aware of the relevant feature(s).

Consumers may still refer such cases to the FOS, but only to check whether the Motor Finance Consumer Redress Scheme rules were followed or pursue a claim in court.

Extension for Handling Motor Finance Complaints

In anticipation of the Hopcraft Decision, the FCA has issued rules to extend the time firms have to respond and issue final responses in relation to motor finance complaints.

Under current rules, firms must start sending final responses to motor finance commission complaints, including those involving DCAs and tied arrangements, from 5 December 2025. However, this would require some firms to issue responses before the FCA concludes the Consultation and confirms whether the proposed redress scheme will proceed.

To avoid inconsistent outcomes and ensure complaints are resolved in an orderly and efficient way, the FCA proposes to extend the deadline for providing final responses to these complaints. This extension would give firms time to align their approach with the final scheme rules and avoid unnecessary duplication or consumer confusion.

It is important to note that the FCA proposes to exclude complaints about leasing agreements from the further extension.

Practical Points for Firms in Scope

The Consultation includes very detailed and prescriptive guidance on how the Motor Finance Consumer Redress Scheme should be implemented by firms. These include monthly data reporting to the FCA to demonstrate progress and compliance, the mandatory use of FCA-prescribed template letters for consumer communications, and a duty to notify the FCA promptly if financial or operational resources are expected to be inadequate. These requirements underline the FCA’s expectation that firms act early, maintain transparency, and ensure robust governance throughout the scheme.

The Dear CEO Letter therefore provides some additional practical guidance on what firms should focus on while the Consultation is ongoing.

The FCA’s Dear CEO Letter makes clear that firms should act now: resolve existing complaints fairly and get ready to deliver the scheme at pace if it proceeds. The FCA states that it will be pragmatic where firms are preparing seriously, but will intervene if they do not.

a. Keep moving on complaints (with two timelines to manage)

Leasing complaints: As mentioned above, the FCA is not proposing a further extension. Firms should plan to resume the standard 8‑week response timelines from 5 December 2025 and give any feedback on this point by 4 November 2025.

Other motor finance commission complaints (non‑leasing): the FCA proposes to extend the deadline to send final responses to 31 July 2026. This is a pause on the final response clock, not a pause on investigation — firms should keep gathering evidence and continue to progress issues that fall outside any scheme (e.g., affordability/forbearance) under normal DISP rules.

b. Build “impacted customer” picture

Lenders should start working to identify and be ready to contact affected customers quickly once the Motor Finance Consumer Redress Scheme has been finalised.

c. Close data gaps with brokers

Lenders should assess what records are needed to test scope and liability. Brokers should prepare by cataloguing lenders used, commission/disclosure records and likely volumes, and by resourcing for lender requests. The FCA expects collaboration to be prompt and constructive.

d. Get case‑handling “fit for scale”

Lenders should review systems and controls to ensure redress can be calculated accurately and consistently at volume. The FCA encourages the use of technology, including AI, where it improves speed and consistency.

e. Resource prudently and avoid steps that hinder redress

Lenders should maintain adequate financial and non‑financial resources, provision or disclose potential liabilities appropriately, and avoid actions (e.g., asset movements, structural changes) that could delay redress. Brokers must also ensure, as a minimum, that they can meet debts as they fall due. Insolvency practitioners appointed over firms should continue to meet regulatory obligations.

f. Put clear senior ownership and robust oversight in place

The FCA expects that Senior Managers at lenders and brokers take responsibility for Motor Finance Consumer Redress Scheme readiness, with appropriate second‑ and third‑line oversight from the outset.

g. Stay open and cooperative with the FCA

The FCA expects that lenders and brokers engage proactively under Principle 11 and make SUP 15 notifications where anything could materially affect their ability to meet obligations (including resource concerns or contemplated transactions).

What Comes Next

The FCA will confirm by 4 December 2025 whether complaint handling deadlines will be extended. If the Motor Finance Consumer Redress Scheme goes ahead, the FCA expects to publish its policy statement and final rules in early 2026, with the Motor Finance Consumer Redress Scheme launching at the same time. On this basis, consumers would begin receiving compensation later in 2026.

What Firms Should Do Now

Lenders and brokers still have a window to influence the design of the eventual Motor Finance Consumer Redress Scheme. We strongly recommend that firms potentially impacted review the Consultation and submit comments on aspects of it that are of concern, e.g. the design, scope, calculation methodologies, opt-in/opt-out proposals. Firms should also engage now with trade bodies, industry groups and their legal advisors so their views are represented as impactfully as possible.

Michigan’s No-Fault Auto Insurance: Navigating Claims After a Hit-and-Run Accident

A hit-and-run accident can leave you feeling shaken and overwhelmed. In Michigan, the no-fault insurance system offers some protections, but recovering compensation after a fleeing driver complicates the process. This blog breaks down what you need to know about no-fault benefits, hit-and-run rules, and your legal options.

Michigan’s No-Fault Insurance System

Michigan law requires all vehicle owners to carry no-fault, or personal injury protection (PIP), insurance. This coverage helps pay for medical expenses, lost wages, attendant care, household services, and other related costs, regardless of who caused the accident.

You can only sue for additional compensation in cases involving serious injuries or specific exceptions. Drivers also have the option to choose from different levels of PIP medical benefits rather than being required to purchase unlimited coverage.

Hit-and-run accident victims can still receive no-fault benefits, including drivers, passengers, pedestrians, and bicyclists. Those without their own insurance may qualify for benefits through Michigan’s Assigned Claims Plan.

If the at-fault driver cannot be identified, you may file a claim under your uninsured motorist (UM) insurance coverage. Many UM policies require a police report to be filed within 24 hours of the accident.

Why Drivers Leave the Scene

Drivers may flee an accident for several reasons:

They are intoxicated or under the influence.

They are driving a stolen vehicle.

They are trying to avoid the police.

They do not have insurance.

They panic or fear legal or financial consequences.

These situations make identifying and holding the responsible party accountable much more difficult.

Can I Sue the Fleeing Driver?

You can pursue a civil lawsuit against the driver only if they are later identified or arrested. If the driver is never identified, filing a lawsuit is not possible, and your recovery will come from your own no-fault or UM insurance coverage.

What Should I Do After a Hit-and-Run?

Following a hit-and-run accident, taking the right steps can help protect your rights and ensure you receive the benefits you are entitled to:

Call the police immediately and file a report. Be sure to include every detail you remember about the other vehicle and the circumstances of the crash.

Take photos of the vehicle damage, the surrounding area, and any evidence such as debris or tire marks.

Seek medical attention right away if you are injured, and save all records of your treatment.

Report the crash promptly to your insurance company.

File your no-fault and UM claims quickly. Michigan law generally requires no-fault claims to be filed within one year, and many insurers may have their own notice deadlines.

Keep records of your injuries, medical expenses, and any correspondence with your insurance company.

Insurance companies sometimes deny or delay valid claims. Speak with a Michigan no-fault insurance lawyer who can help you handle disputes and make sure all deadlines and requirements are met.

Conclusion

Recovering from a hit-and-run accident in Michigan can feel stressful, but your insurance benefits are designed to help. No-fault coverage can pay for medical bills, lost income, and other expenses, and uninsured motorist coverage may provide additional protection if the driver is never found.

Navigating claims and dealing with insurance companies can be complex, so having experienced legal guidance makes a significant difference.

Ninth Circuit Finds Class Certification Inappropriate in Case Involving Projected Sold Adjustments on Auto Insurance Total Losses

A recent Ninth Circuit decision reconciled other decisions within that circuit involving auto insurance total losses, concluding that individual questions predominated and therefore affirming the district court’s denial of class certification. The dissent, however, called for en banc review, suggesting that an intra-circuit split exists.

In Ambrosio v. Progressive Preferred Insurance Company, – F. 4th –, 2025 WL 2628179 (9th Cir. Sept. 12, 2025), the plaintiffs brought a putative class action against Progressive, alleging that it improperly used a “projected sold adjustment” (PSA) to calculate the actual cash value (ACV) of their totaled vehicles. The PSA was used to adjust list prices of comparable vehicles to reflect negotiations at the time of sale. The plaintiffs claimed this resulted in undervaluation and a breach of contract. The district court declined to certify the proposed class on the grounds that individualized issues would predominate, and the plaintiffs appealed.

Affirming the district court, the Ninth Circuit found that the PSA was not facially unlawful under the policies defining ACV based on market value because each insured would need to compare the allegedly flawed “market value” with a correct one to win on the merits. The court noted that the PSA was designed to reflect consumer purchasing behavior and was not unlawful under Arizona law, distinguishing another similar Ninth Circuit case involving a Washington statute. The plaintiffs argued that the PSA always resulted in an undervaluation, but the court disagreed. It explained that “[w]e cannot now read an unwritten requirement into the contract of how to calculate ‘market value,’” and “[i]f the appraisal from [Progressive’s vendor] resulted in a fair ‘market value’ assessment, even while using the PSA, then the ACV would be accurate, and there would be no injury.” Moreover, “[t]his is not a dispute over the amount of any individual’s damages … but over an essential element of each individual [putative class member’s] claim,” i.e., injury. Progressive had demonstrated that it, if a factfinder accepted its evidence from “blue book” type sources, it could prove that, for at least two putative class members, the vehicle’s market value was higher than the amount paid. The majority noted that “denying Progressive this defense altogether would seem to violate due process.”

Judge Wallach of the Federal Circuit, sitting by designation, dissented. The dissent concluded that the PSA was a one-sided deduction that did not fit the contract’s requirement to determine ACV. The dissent criticized Progressive’s evidence of market value as inconsistent with how the claims were adjusted. It concluded that the district court should have certified the class and then interpreted the policy at the summary judgment stage or trial. The dissent acknowledged, however, that the majority opinion was consistent with recent decisions by the Third, Fourth and Seventh Circuits, all in similar cases involving Progressive’s use of PSAs. The dissent also suggested that en banc review may be appropriate.

The majority opinion highlighted a couple of defense strategies that I have often mentioned on this blog, and which were successful here. First, demonstrate how individual putative class members’ cases would be tried if they were individual cases, with specific evidence showing a lack of injury. Second, stress that the defendant cannot be deprived of presenting those defenses merely because of the plaintiff’s desire for class treatment. The class action mechanism is not supposed to alter the parties’ substantive rights.

Consumer Legal Funding Explained: Evidence Versus Assumptions

Consumer Legal Funding (CLF) provides injured individuals with small amounts of money to cover everyday living expenses while their legal claims move through the system. It is a non-recourse transaction: if the consumer does not recover, they owe nothing. For many families, this is the only way to keep food on the table and the lights on while they wait for a fair settlement.

Yet despite its narrow scope and consumer-focused purpose, CLF has faced strong opposition. Insurance companies and defense interests frequently claim it drives up litigation costs, prolongs cases, exploits consumers, and inflates settlements. These objections are often presented as fact, but a closer look reveals that they are based on misconceptions, exaggerations, and, in some cases, deliberate conflation with other forms of litigation financing.

This article addresses the seven most common objections to Consumer Legal Funding and demonstrates why they are wrong.

Objection 1: “CLF Increases Litigation Costs”

Opponents argue that by giving consumers money to survive, CLF somehow causes lawsuits to become more expensive. The claim is that plaintiffs, no longer financially desperate, reject early settlement offers and demand more, which in turn drives up insurance payouts.

Why This Is Wrong:- CLF funds are used for survival, not litigation. Consumers spend this money on rent, groceries, transportation, and utilities. It does not finance attorney fees, depositions, or expert witnesses.- Settlements reflect case value, not funding. The only reason a settlement increases is because an insurer initially offered less than what the claim was worth. CLF enables consumers to wait for a fair resolution, not inflate claims.- No empirical evidence supports the claim. In states that regulate CLF — including Ohio, Utah, and Oklahoma, insurance rates have followed national trends, with no spike attributable to CLF.

Reality: CLF doesn’t increase litigation costs; it prevents insurers from exploiting financial desperation to settle cases cheaply.

Objection 2: “CLF Prolongs Litigation”

Insurers claim that with CLF, plaintiffs can afford to “hold out,” causing unnecessary delays in court and prolonging the resolution of cases.

Why This Is Wrong:- Delays come from the courts, not consumers. Court backlogs, discovery disputes, and insurer tactics are the leading causes of delay.- Consumers want resolution. No injured person wants to stay in litigation longer than necessary. CLF allows them to pay their bills while the process unfolds.- Data disproves the claim. To our knowledge states with regulated CLF have not seen longer case durations compared to states without it.

Reality: CLF doesn’t prolong litigation; it helps consumers survive while insurers and courts take the time they need to resolve cases.

Objection 3: “CLF Exploits Consumers”

Opponents often frame CLF as predatory, likening it to payday loans. They argue that fees and repayment amounts are high and unfair.

Why This Is Wrong:- CLF is non-recourse. Unlike payday loans and other loans, if the consumer loses their case, they owe nothing. These shifts risk away from the consumer.- Consumers choose CLF voluntarily. Individuals review the terms, with legal counsel, and decide if it’s the best option.- The alternative is worse. Without CLF, consumers may face eviction, bankruptcy, or be forced to accept an inadequate settlement.- Costs reflect high risk. Many cases result in no recovery for the funder, so pricing reflects that risk.

Reality: CLF empowers consumers by offering them a risk-free option. Far from being exploitative, it fills a gap where traditional credit products do not work.

Objection 4: “CLF Creates Conflicts of Interest”

Critics argue that third-party funders could influence litigation strategy, interfering with the attorney-client relationship.

Why This Is Wrong:- CLF contracts prohibit interference. In states where CLF is regulated, statutes make clear that funders cannot direct or control litigation decisions.- Consumers remain in charge. The plaintiff, with their lawyer, decides when to settle and for how much.- This is a red herring. There are no documented cases of CLF interfering with attorney-client relationships under regulated frameworks.

Reality: CLF companies have no control over litigation. Decisions remain with the attorney and client.

Objection 5: “CLF Reduces Settlement Incentives”

The claim here is that because consumers can afford to wait, they are less inclined to settle, leading to unnecessary trials.

Why This Is Wrong:- CLF corrects imbalance, it doesn’t distort it. Insurers routinely offer “lowball” settlements, knowing financial hardship forces people to accept them. CLF restores the consumer’s ability to reject unfair offers.- Cases still settle. Over 90% of civil cases nationwide settle. CLF does not change this fact.- Settlement is still in the plaintiff’s interest. Consumers and lawyers have no incentive to prolong litigation unnecessarily.

Reality: CLF doesn’t reduce incentives to settle; it reduces the leverage insurers hold over financially vulnerable people.

Objection 6: “CLF Lacks Transparency”

Opponents push for mandatory disclosure of CLF contracts, claiming defendants should know if a plaintiff has obtained funding.

Why This Is Wrong:- Irrelevant to the case merits. Whether a consumer has received CLF has no bearing on liability or damages.- Creates prejudice. Disclosure would allow insurers to use funding against consumers, arguing they are motivated by profit rather than justice.- No similar disclosure exists. Consumers are not required to disclose their bank accounts as an example.

Reality: CLF contracts are private, irrelevant to case facts, and disclosure rules would only harm consumers.

Objection 7: “CLF Raises Insurance Premiums”

Perhaps the most common accusation is that CLF drives up insurance rates, increasing costs for all consumers.

Why This Is Wrong:- No actuarial evidence supports this. In states with CLF statutes, insurance rates follow the same trajectory as states without CLF.- Premiums rise due to other factors. Medical inflation, jury awards, and market conditions are the real cost drivers.- Scapegoating at work. Blaming CLF is politically convenient but doesn’t reflect reality.

Reality: There is no evidence CLF raises premiums. Insurers use this claim as a distraction from real causes of cost increases.

Conclusion: Empowering Consumers, Not Burdening the System

Every objection raised against Consumer Legal Funding collapses under scrutiny. The product does not increase litigation costs, prolong cases, or inflate settlements. It does not exploit consumers or interfere with the attorney-client relationship. And it certainly does not raise insurance premiums.

What CLF does is provide vulnerable individuals with a measure of financial dignity. It helps them avoid forced settlements, stay afloat during litigation, and pursue justice without being crushed by economic hardship. Insurers oppose CLF not because it harms consumers, but because it limits their ability to exploit consumer vulnerability for profit.

As policymakers and regulators evaluate CLF, they should separate fact from fiction. The evidence is clear: Consumer Legal Funding is not the problem. It is part of the solution, a free-market, risk-sharing tool that helps ordinary people survive the long wait for justice.

Consumer Legal Funding: Funding Lives, Not Litigation

The ADGM Court Confirms its Jurisdiction to Issue Anti-Suit Injunctions to Restrain Onshore Court Proceedings

Introduction

On 13 August 2025, the Abu Dhabi Global Market (ADGM) Court of First Instance (Court of First Instance), in its judgment in A22 and B22 v. C22 [2025] ADGMCFI 0018, confirmed that the ADGM Courts have jurisdiction to issue an anti-suit injunction restraining onshore Abu Dhabi court proceedings where it would be “just and convenient” to do so. However, on the facts, the Court of First Instance declined to grant the requested relief.

Background

The underlying dispute arose out of a payout under an insurance policy that D22 (Contractor) took out with C22 (Insurer) (Policy). As required by the Policy, the Contractor engaged A22, a marine warranty surveyor (Surveyor), for services relating to the loadout and transportation of items for the project (Services). The engagement was made under a letter of intent, which contemplated that the parties would enter a formal service order (Service Order). The Service Order, which was only executed about a year after the Services had been performed, stated that it was subject to the Surveyor’s general terms and conditions, which provides for disputes to be resolved by arbitration under the arbitration rules of the International Chamber of Commerce, seated in Abu Dhabi (Arbitration Agreement).

During the performance of the Services, some equipment was damaged, and the Contractor claimed for loss under the Policy. After indemnifying the Contractor, the Insurer commenced proceedings in the Abu Dhabi onshore courts against the Contractor, the Surveyor and another related entity, B22 (Co-Defendant), to recover the payout. The defendants raised a jurisdictional objection based on the Arbitration Agreement but nonetheless participated in the court proceedings.

Partway through the onshore court proceedings, the Surveyor and Co-Defendant sought an anti-suit injunction from the ADGM Courts to prevent the Insurer from continuing the onshore court proceedings in light of the Arbitration Agreement contained in the Surveyor’s general terms and conditions, referred to in the contract between the Contractor and the Surveyor. The Contractor and the Surveyor took the position that the Insurer was bound by the Arbitration Agreement on the basis that the onshore court proceedings had been brought under asserted subrogation rights which became operative after the insurance moneys were paid to the Contractor.

Judgment of the ADGM Court of First Instance

The Court of First Instance was required to consider whether it had jurisdiction to entertain the application for an interim anti-suit injunction and if jurisdiction were to exist, whether the Court of First Instance should exercise it in favour of the Surveyor and Co-Defendant.

On the first issue, the Court of First Instance held that it had jurisdiction to issue an interim anti-suit injunction restraining onshore court proceedings by virtue of sections 16 and 41 of the ADGM Courts, Civil Evidence, Judgments, Enforcement and Judicial Appointments Regulations 2015 (the ADGM Courts Regulations). Section 16(2)(c) of the ADGM Courts Regulations states that the Court of First Instance may exercise any jurisdiction conferred upon it by the ADGM Courts Regulations and section 41 is the principal source of jurisdiction for an anti-suit injunction application (whether interim or final). In reaching this decision, the Court of First Instance noted that section 41 of the ADGM Court Regulations provides the same jurisdiction as section 37(1) and (2) of the United Kingdom (UK) Senior Courts Act 1981 and that the UK Supreme Court had confirmed the ability of the court to issue anti-suit injunctions under that section.

Having found jurisdiction, the Court of First Instance then considered whether it would be “just and convenient”—the language used in section 41(1) of the ADGM Courts Regulations—to grant the requested relief.

When considering the meaning of “just and convenient”, the Court of First Instance cited the principles adopted by Foxton J in QBE Europe SA/NV v Generali Espana de Seguros y Reaseguros [2022] EWHC 2062 (Comm), as follows:

The touchstone for making an order is what the ends of justice require;

The jurisdiction should be exercised with caution;

The applicant must establish with a “high degree of probability” that there is an arbitration agreement governing the dispute in question; and

A defendant must show “strong reasons” why relief should not be granted, if such an agreement can be established to that standard.

Regarding the question of whether the Surveyor and Co-Defendant had established to “a high degree of probability” that there is a valid arbitration agreement governing the dispute in question, the Court of First Instance noted that this would necessarily require judicial evaluation of the likelihood of a valid arbitration agreement being established at the necessary time. The Court of First Instance stated that although Federal Law No. 6 of 2018—the procedural law governing arbitrations seated in Abu Dhabi—expressly permits the incorporation of an arbitration agreement by reference, further submissions would be required to determine whether the Arbitration Agreement in the Surveyor’s general terms and conditions had been validly incorporated. In any event, the Court of First Instance held that there were other reasons which rendered it unable to conclude that there is a “high degree of probability” of a valid arbitration agreement, such as the timing of execution of the Service Order (one year after the event that gave rise to the claim) and the fact that the Co-Defendant was not a party to the contract in which the arbitration agreement was alleged to reside.

The Court of First Instance further held that, even if it was wrong on this issue, it would still have exercised its discretion not to grant an interim order. This was in part because the order was only sought after the panel of experts had issued an adverse report in the onshore court proceedings, and because the Court of First Instance felt it was not appropriate to interfere with the processes of the onshore court. The Court of First Instance stated that it was not unusual for the onshore courts to defer making a decision on jurisdiction until judgment on the merits is given, and therefore, it would not be appropriate to interfere with that process and any subsequent rights of appeal.

Conclusion

This judgment is significant because it demonstrates that the ADGM Courts have jurisdiction over a claim for an anti-suit injunction restraining onshore court proceedings notwithstanding that the seat of the arbitration (assuming the arbitration agreement is found to be valid) is outside the ADGM (in this case, the seat of arbitration was Abu Dhabi). It also serves to emphasise the importance of parties acting promptly to seek to restrain court proceedings filed in violation of an arbitration agreement. In this regard, the Court of Appeal noted that, whilst delay is not necessarily a bar to relief, the court can refuse relief on the grounds of delay if the circumstances of the particular case so demand.

Ten Minute Interview: Unique Insurance Considerations for High Net Worth Individuals [Video]

Brian Lucareli, director of Foley Private Client Services (PCS) and co-chair of the Family Offices group, sits down with Ethan Lenz, partner and former chair of our Insurance practice, for a 10-minute interview to discuss unique insurance considerations for high net worth individuals and family offices. During the session, Ethan provided an overview of the type of insurance high net worth individuals and family offices should consider and the associated risks. He also touched on the insurance considerations for family office portfolio companies and investments.

Unusual Receivership Assets

When most people think of receiverships, they picture foreclosed real estate or distressed companies with familiar assets. But not every case fits neatly into that mold. Sometimes, receivers are asked to manage assets that are unconventional, difficult to value, or loaded with unique legal obligations.

Unusual receivership assets demand creativity, legal savvy, and financial discipline. By reviewing several unique scenarios below, we’ll highlight just how adaptable receiverships can be.

Why Receiverships Are Gaining Attention

Receiverships are gaining traction as an alternative to bankruptcy in cases involving unusual or sensitive assets. State legislatures, including Missouri, with its Commercial Receivership Act, are updating statutes to provide clearer authority.

Part of the growing popularity of receiverships stems from their efficiency. Bankruptcy cases can be lengthy and expensive, while receiverships often move faster and with fewer administrative costs. This can be particularly attractive in mid-market cases where time and money are limited.

Legislative reforms, such as those in Missouri and other states, aim to standardize procedures and give courts clearer guidance. As these reforms spread, practitioners expect receiverships to be used more frequently, even in industries that historically relied on bankruptcy.

Receiverships as Flexible Legal Tools

Receivership is a state-law remedy that allows a neutral third party, the receiver, to step in and preserve, manage, or sell assets. Unlike bankruptcy, which is a federal process, receiverships operate in state courts and can be tailored to the circumstances of a case.

As Eric Peterson of Spencer Fane LLP notes, “The beauty of receivership is its flexibility. You can craft an appointment order that fits the unique facts, but that flexibility also means you need to be precise. The order is your roadmap.”

That roadmap is particularly important when the assets are non-traditional. Appointment orders should define the receiver’s powers clearly, anticipate regulatory or industry-specific hurdles, and secure funding sources for administration.

Receiverships often work best when the appointment order is drafted with creativity. Courts can authorize the receiver not only to take custody of assets but also to operate businesses, sell assets as going concerns, or engage with regulators. This flexibility distinguishes receiverships from more rigid bankruptcy procedures.

Still, the flip side of flexibility is uncertainty. Because receiverships are governed primarily by state law, standards and practices can vary widely. In some jurisdictions, judges are very familiar with commercial receiverships, and in others, less so. That means parties should not assume consistency from one case to another.

Livestock Operations

Few assets create more complexity than a living herd. Brent King of B. Riley Financial has worked on agricultural receiverships involving pork processing, beef and dairy production, and crop operations. He emphasizes that the receiver’s role is not just financial but operational.

“From farrow to harvest, you’re talking about herd management, feed, growth monitoring, and animal welfare. These aren’t just numbers on a balance sheet; these are living assets,” advises King.

Livestock raises immediate concerns about funding. Feed costs are daily and non-negotiable, and a cash-strapped estate may have no liquidity. Courts must often approve emergency financing to preserve herd value. Environmental and animal welfare regulations add further oversight.

The operational challenges go beyond feed and veterinary care. A receiver may also need to manage breeding schedules, disease prevention protocols, and contracts with processors or distributors. Weather, commodity prices, and biosecurity issues can all influence herd value. Failure to act quickly can turn a viable operation into a distressed liquidation within weeks.

Financial reporting also plays a role. Lenders and courts need transparency on herd counts, feed usage, and mortality rates. Receivers often must implement rapid reporting systems to reassure stakeholders that value is being preserved.

Fertility Clinics and the Question of Frozen Embryos

Perhaps no example captures the legal and ethical complexity of unusual receivership assets better than fertility clinics.

“You can’t just treat frozen embryos like equipment. State laws differ on whether they’re considered property or potential persons, and you have to deal with patients, regulators, and law enforcement all at once,” cautions Jeremiah Foster of Resolute Commercial.

Receivership of fertility clinics requires careful mapping of the asset pool: medical equipment, lab inventory, intellectual property, and patient contracts. But frozen embryos raise thorny questions. Some states impose restrictions on transfer or destruction, and recent legal debates after the fall of Roe v. Wade have intensified scrutiny.

Receivership in a healthcare setting also implicates confidentiality laws. Patient records are protected under HIPAA, meaning the receiver must maintain strict compliance in how data is accessed, stored, or transferred. This can require special training for staff and careful coordination with regulators.

The ethical dimensions are particularly acute with embryos. Courts may need to consider questions of consent if former patients cannot be located or disagree on disposition. In some states, public policy leans toward treating embryos as property, while in others, courts are cautious about authorizing their destruction or transfer. These conflicting approaches place receivers in sensitive positions where legal advice is critical.

Auto Dealerships

Auto dealerships appear straightforward at first glance, but as Baker Smith of BDO Consulting Group, LLC points out, they are ‘ecosystems’ with layers of financial and legal complexity: “Cash flow doesn’t come from sales alone; it’s manufacturer rebates, finance and insurance, service, and parts. If you don’t understand that ecosystem, you won’t understand the value.”

Receivers of dealerships must navigate floor plan financing arrangements, where vehicles on the lot are financed by lenders. If cars are sold ‘out of trust,’ without repaying the floor plan lender, it can quickly spiral into fraud allegations. Curtailment obligations, title transfers, and manufacturer approvals add more hurdles.

Service departments and parts inventories are often the most profitable components of dealerships. Preserving staff in these areas can be essential to maintaining going-concern value. However, labor contracts and customer warranties complicate matters, and receivers must quickly determine which obligations they can and cannot honor.

Marketing and reputation management also matter. Unlike some businesses, dealerships depend heavily on community perception and repeat customers. A receiver stepping in must balance immediate cost-cutting with long-term brand value.

The Commonalities

Though the assets differ in each scenario, certain themes emerge across them all:

The Appointment Order is critical. It defines the receiver’s powers and can shield them from liability.

Funding must be addressed early. From feed to payroll, many unusual assets require immediate cash infusions.

Industry expertise matters. Receivers may need to hire specialists, i.e., veterinarians, lab directors, dealership managers, to stabilize operations.

Stakeholder management is essential. Patients, regulators, and employees all require communication and coordination.

Another recurring theme is the tension between speed and thoroughness. Courts and creditors often want a fast resolution, but rushing can create mistakes, such as overlooking regulatory filings or mishandling sensitive assets, that generate liability. Receivers must strike a balance between moving quickly enough to preserve value and carefully enough to avoid errors.

Funding sources can also be creative. Some courts authorize receiver’s certificates, which function like high-priority loans secured by estate assets. While helpful, they can be controversial among existing creditors because they alter repayment priorities.

Conclusion

Receiverships may never replace bankruptcy, but as more courts embrace their adaptability, they will remain a vital tool for handling the assets that don’t fit the mold.

When approaching a receivership, practitioners should:

Secure funding immediately. Without cash, herds starve, employees leave, and patients panic.

Assess insurance coverage early. Liability insurance for directors, officers, or healthcare providers may extend to receivership operations, but only if policies are preserved and premiums kept current.

Draft the appointment order carefully. Anticipate regulatory, ethical, and operational issues.

Engage industry experts early. Don’t assume a generalist can manage a specialized business.

Prioritize communication. Transparency with stakeholders builds trust and avoids disputes.

Plan for exit. Whether through asset sales, transitions to new operators, or wind-downs, know the likely endgame.

This article was originally published on October 2, 2025 here.

Recent Mass. Chapter 93A Case Highlights Key Distinctions Between Sections 9 and 11

In Sentinel Ins. Co., Ltd. v. Broan-Nutone, LLC, 2025 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 184988, the plaintiff (the Insurer), as subrogee of the Assembly of Christians Gospel Hall Association (the Insured), brought a products liability claim against Broan after a ventilation fan allegedly caused a fire that damaged the Insured’s property. The Insured asserted breach of warranty, negligence, and Chapter 93A claims under both Section 9 and Section 11. After discovery ended, Broan moved for partial summary judgment on both the Chapter 93A claims, among other things.

The court granted summary judgment for Broan on the Chapter 93A claims. In doing so, the court first drew an important distinction between Section 9 and Section 11 claims, because the Insured had not sent a pre-suit demand letter. As the court noted, Section 9 applies to consumer claims and requires a demand letter before filing suit, unless the defendant does not maintain a place of business or assets in Massachusetts. Section 11, which does not require the sending of a pre-suit demand letter, applies to business claims if the unfair acts or practices occurred “primarily and substantially” within the commonwealth. The Insurer initially based its claim on Section 11 but later switched, arguing that Section 9 should apply because the Insured is a church corporation and not a business within the meaning of Chapter 93A.

As to Section 11, the court found that the “center of gravity” of the alleged unfair conduct (design, manufacture, testing, and sale of the fan) occurred outside Massachusetts. The place of injury (the fire in Massachusetts) was not sufficient to establish that the actionable conduct occurred “primarily and substantially” within the Commonwealth and, therefore, the Insured could not sustain a Section 11 claim.

As to Section 9, the court concluded that the complaint did not allege facts showing Broan lacked a place of business or assets in Massachusetts, which is necessary to invoke the exception to the demand letter requirement. The Insurer conceded this fact and suggested that it would seek leave to file an amended complaint, but the court noted this would be difficult given the late stage of litigation. As the court explained: “The Court is not today deciding if such a motion for leave to file an amended complaint would be viable but notes that this case was removed to this Court 28 months ago on April 10, 2023, discovery closed 5 months ago on March 10, 2025, and this matter is scheduled for trial on November 17, 2025.” As a result, the court held that the Insurer’s Chapter 93A claim failed under both Section 9 and Section 11. This case demonstrates the differences between Section 9 and 11 and the importance of making sure the claimant is proceeding under the correct section and satisfies the requirements for the chosen section. It also highlights a potential defense strategy of waiting to seek summary judgment on the claim after discovery ends and when a claimant’s proof fails to satisfy those requirements.

Healthcare AI in the United States — Navigating Regulatory Evolution, Market Dynamics, and Emerging Challenges in an Era of Rapid Innovation

The use of artificial intelligence (AI) tools in healthcare continues to evolve at an unprecedented pace, fundamentally reshaping how medical care is delivered, managed, and regulated across the United States. As 2025 progresses, the convergence of technological innovation, regulatory adaptation (or lack thereof), and market shifts has created remarkable opportunities and complex challenges for healthcare providers, technology developers, and federal and state legislators and regulatory bodies alike.

The rapid proliferation of AI-enabled medical devices represents perhaps the most visible manifestation of this transformation. With nearly 800 AI- and machine learning (ML)-enabled medical devices authorized for marketing by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the five-year period ending September 2024, the regulatory apparatus has been forced to adapt traditional frameworks designed for static devices to accommodate dynamic, continuously learning algorithms that evolve after deployment. This fundamental shift has prompted new approaches to oversight, such as the development of predetermined change control plans (PCCPs) that allow manufacturers to modify their systems within predefined parameters and without requiring additional premarket submissions.

Regulatory Frameworks Under Pressure

The regulatory environment governing healthcare AI reflects the broader challenges facing federal agencies as they attempt to balance innovation and patient safety. The FDA’s approach to AI-enabled software as a medical device (SaMD) has evolved significantly, culminating in the January publication of comprehensive draft guidance addressing life cycle management and marketing submission recommendations for AI-enabled device software functions. This guidance represents a critical milestone in establishing clear regulatory pathways for AI and ML systems that challenge traditional notions of device stability and predictability.

The traditional FDA paradigm of medical device regulation was not designed for adaptive AI and ML technologies. This creates unique challenges for continuously learning algorithms that may evolve after initial market authorization. The FDA’s January 2021 AI/ML-based SaMD Action Plan outlined five key actions based on the total product life cycle approach: tailoring regulatory frameworks with PCCPs, harmonizing good ML practices, developing patient-centric approaches, supporting bias elimination methods, and piloting real-world performance monitoring.

However, the regulatory landscape remains fragmented and uncertain. The rescission of the Biden administration’s Executive Order (EO) 14110, “Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence,” by the Trump administration and the current administration’s issuance of its own EO on AI, “Removing Barriers to American Leadership in Artificial Intelligence,” in January has created additional uncertainty regarding federal AI governance priorities. While the Biden administration’s EO has been rescinded, its influence persists through agency actions already underway, including the April 2024 Affordable Care Act (ACA) Section 1557 final rule on nondiscrimination in health programs run by the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the final rule on algorithm transparency in the Office for Civil Rights. Consequently, enforcement priorities and future regulatory development remain uncertain.

State-level regulatory activity has attempted to fill some of these gaps, with 45 states introducing AI-related legislation during the 2024 session. California Assembly Bill 3030, which specifically regulates generative AI (gen AI) use in healthcare, exemplifies the growing trend toward state-specific requirements that healthcare organizations must navigate alongside federal regulations. This patchwork of state and federal requirements creates particularly acute challenges for healthcare AI developers and users operating across multiple jurisdictions.

Data Privacy and Security: The HIPAA Challenge

One of the most pressing concerns facing healthcare AI deployment involves the intersection of AI capabilities and healthcare data privacy requirements. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) was enacted long before the emergence of modern AI systems, creating significant compliance challenges as healthcare providers increasingly rely on AI tools for clinical documentation, decision support, and administrative functions.

The use of AI-powered transcription and documentation tools has emerged as a particular area of concern. Healthcare providers utilizing AI systems for automated note-taking during patient encounters face potential HIPAA violations if proper safeguards are not implemented. These systems often require access to comprehensive patient information to function effectively, yet traditional HIPAA standards may conflict with AI systems’ need for extensive datasets to optimize performance. AI tools must be designed to access and use only the protected health information (PHI) strictly necessary for their purpose, even though AI models often require comprehensive datasets to achieve their full potential.

The proposed HHS regulations issued in January attempt to address some of these concerns by requiring covered entities to include AI tools in their risk analysis and risk management compliance activities. These requirements mandate that organizations conduct vulnerability scanning at least every six months and penetration testing annually, recognizing that AI systems introduce new vectors for potential data breaches and unauthorized access.

Business associate agreements (BAAs) have become increasingly complex as organizations attempt to address AI-specific risks. These agreements must now encompass algorithm updates, data retention policies, and security measures for ML processes, while ensuring that AI vendors processing PHI operate under robust contractual frameworks that specify permissible data uses and required safeguards. Healthcare organizations must ensure that AI vendors processing PHI operate under robust BAAs that specify permissible data uses and necessary security measures and account for AI-specific risks related to algorithm updates, data retention policies, and other ML processes.

Algorithmic Bias and Health Equity Concerns

The potential for algorithmic bias in healthcare AI systems has emerged as one of the most significant ethical and legal challenges facing the industry. A 2024 review of 692 AI- and ML-enabled FDA-approved medical devices revealed troubling gaps in demographic representation, with only 3.6% of approved devices reporting race and ethnicity data, 99.1% providing no socioeconomic information, and 81.6% failing to report study subject ages.

These data gaps have profound implications for health equity, as AI systems trained on nonrepresentative datasets may perpetuate or exacerbate existing healthcare disparities. Training data quality and representativeness significantly — and inevitably — impact AI system performance across diverse patient populations. The challenge is particularly acute given the rapid changes in federal enforcement priorities regarding diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives.

While the April 2024 ACA Section 1557 final rule regarding HHS programs established requirements for healthcare entities to ensure AI systems do not discriminate against protected classes, the current administration’s opposition to DEI initiatives has created uncertainty about enforcement mechanisms and compliance expectations. Given the rapid turnabout in executive branch policy toward DEI and antidiscrimination initiatives, it remains to be seen how federal healthcare AI regulations with respect to bias and fairness will be affected.

Healthcare organizations are increasingly implementing systematic bias testing and mitigation strategies throughout the AI life cycle, focusing on validating the technology, promoting health equity, ensuring algorithmic transparency, engaging patient communities, identifying fairness issues and trade-offs, and maintaining accountability for equitable outcomes. AI system developers have, until recently, faced increasing regulatory pressure to ensure training datasets adequately represent diverse patient populations. And most healthcare AI developers and practitioners continue to maintain that relevant characteristics, including age, gender, sex, race, and ethnicity, should be appropriately represented and tracked in clinical studies to ensure that results can be reasonably generalized to the intended-use populations.

However, these efforts often occur without clear regulatory guidance or standardized methodologies for bias detection and remediation. Special attention must be paid to protecting vulnerable populations, including pediatric patients, elderly individuals, racial and ethnic minorities, and individuals with disabilities.

Professional Liability and Standards of Care

The integration of AI into clinical practice has created novel questions about professional liability and standards of care that existing legal frameworks struggle to address. Traditional medical malpractice analysis relies on established standards of care, but the rapid evolution of AI capabilities makes it difficult to determine what constitutes appropriate use of algorithmic recommendations in clinical decision-making.

Healthcare AI liability generally operates within established medical malpractice frameworks that require the establishment of four key elements: duty of care, breach of that duty, causation, and damages. When AI systems are involved in patient care, determining these elements becomes more complex. While a physician must exercise the skill and knowledge normally possessed by other physicians, AI integration creates uncertainty about what constitutes reasonable care.

The Federation of State Medical Boards’ April 2024 recommendations to hold clinicians liable for AI technology-related medical errors represent an attempt to clarify professional responsibilities in an era of algorithm-assisted care. However, these recommendations raise complex questions about causation, particularly when multiple factors contribute to patient outcomes and AI systems provide recommendations that healthcare providers may accept, modify, or reject based on their clinical judgment.

When algorithms influence or drive medical decisions, determining responsibility for adverse outcomes presents novel legal challenges not fully addressed in existing liability frameworks. Courts must evaluate whether AI system recommendations served as a proximate cause of patient harm as well as the impacts of the healthcare provider’s independent medical judgment and other contributing factors.

Documentation requirements have become increasingly important, as healthcare providers must maintain detailed records of AI system use, including the specific recommendations provided, the clinical reasoning for accepting or rejecting algorithmic guidance, and any modifications made to AI-generated suggestions. These documentation practices are essential for defending against potential malpractice claims while ensuring that healthcare providers can demonstrate appropriate clinical judgment and professional accountability.

AI-related malpractice cases may require expert witnesses with specialized knowledge of medical practice and existing AI technology capabilities and limitations. Such experts should have the experience necessary to evaluate whether healthcare providers used AI systems in an appropriate manner and whether algorithmic recommendations met relevant standards. Plaintiffs in AI-related malpractice cases face challenges proving that AI system errors directly caused patient harm, particularly when healthcare providers retained decision-making authority.

Market Dynamics and Investment Trends

Despite regulatory uncertainties, venture capital investment in healthcare AI remains robust, with billions of dollars allocated to startups and established companies developing innovative solutions. However, investment patterns have become more selective, focusing on solutions that demonstrate clear clinical value and regulatory compliance rather than pursuing speculative technologies without proven benefits.

The American Hospital Association’s early 2025 survey of digital health industry leaders revealed cautious optimism, with 81% expressing positive or cautiously optimistic outlooks for investment prospects and 79% indicating plans to pursue new investment capital over the next 12 months. This suggests continued confidence in the long-term potential of healthcare AI despite near-term regulatory and economic uncertainties.

Clinical workflow optimization solutions, value-based care enablement platforms, and revenue cycle management technologies have attracted significant funding, reflecting healthcare organizations’ focus on addressing immediate operational challenges while building foundations for more advanced AI applications. The increasing integration of AI into these core healthcare functions demonstrates the technology’s evolution from experimental applications to essential operational tools.

Major technology corporations are driving significant innovation in healthcare AI through substantial research and development investments. Companies such as Google Health, Microsoft Healthcare, Amazon Web Services, and IBM Watson Health continue to develop foundational AI platforms and tools. Large health systems and academic medical centers lead healthcare AI adoption through dedicated innovation centers, research partnerships, and pilot programs, often serving as testing grounds for emerging AI technologies.

Pharmaceutical companies increasingly integrate AI throughout drug development pipelines, from target identification and molecular design to clinical trial optimization and regulatory submissions. These investments aim to reduce development costs and timelines while improving success rates for new therapeutic approvals.

Large healthcare technology companies increasingly acquire specialized AI startups to integrate innovative capabilities into comprehensive healthcare platforms. These acquisitions accelerate technology deployment while providing startups with the resources necessary for large-scale implementation and regulatory compliance.

Emerging Technologies and Integration Challenges

The rapid advancement of gen AI technologies has introduced new regulatory and practical challenges for healthcare organizations. As of late 2023, the FDA had not approved any devices relying on purely gen AI architectures, creating uncertainty about the regulatory pathways for these increasingly sophisticated technologies. Gen AI’s ability to create synthetic content, including medical images and clinical text, requires new approaches to validation and oversight that traditional medical device frameworks may not adequately address.

The distinction between clinical decision support tools and medical devices remains an ongoing area of regulatory clarification. Software that provides information to healthcare providers for clinical decision-making may or may not constitute a medical device depending on the specific functionality and level of interpretation provided.

Healthcare AI systems must provide sufficient transparency to enable healthcare providers to understand system recommendations and limitations. The FDA emphasizes the importance of explainable AI that allows clinicians to understand the reasoning behind algorithmic recommendations. AI systems must provide understandable explanations for their recommendations, which healthcare providers in turn use to communicate with patients.

The integration of AI with emerging technologies such as robotics, virtual reality, and internet of medical things (IoMT) devices creates additional complexity for healthcare organizations attempting to navigate regulatory requirements and clinical implementation challenges. These convergent technologies offer significant potential benefits but also introduce new risks related to cybersecurity, data privacy, and clinical safety that existing regulatory frameworks struggle to address comprehensively.

AI-enabled remote monitoring systems utilize wearable devices, IoMT sensors, and mobile health applications to continuously track patients’ vital signs, medication adherence, and disease progression. These technologies enable early intervention for deteriorating conditions and support chronic disease management outside traditional healthcare settings, but they face unique regulatory challenges related to device performance, user training, and clinical oversight.

Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Considerations

Healthcare data remains a prime target for cybersecurity threats, with data breaches involving 500 or more healthcare records reaching near-record numbers in 2024, continuing an alarming upward trend. Healthcare data remains a prime target for hackers due to its high value on black markets and the critical nature of healthcare operations, which makes organizations more likely to pay ransoms.

The integration of AI systems, which often require access to vast amounts of patient data, further complicates the security landscape and creates new vulnerabilities that organizations must address through robust security frameworks. Healthcare organizations face substantial challenges integrating AI tools into existing clinical workflows and electronic health record systems. Technical interoperability issues, user training requirements, and change management processes require significant investment and coordination across multiple departments and stakeholders.

The Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023’s requirement for cybersecurity information in premarket submissions for “cyber devices” represents an important step in addressing these concerns, but the rapid pace of AI innovation often outstrips the development of adequate security measures. Medical device manufacturers must now include cybersecurity information in premarket submissions for AI-enabled devices that connect to networks or process electronic data.

Healthcare organizations must implement comprehensive cybersecurity programs that address not only technical vulnerabilities but also the human factors that frequently contribute to data breaches. Strong technical safeguards must be implemented when using de-identified data for AI training, including access controls, encryption, audit logging, and secure computing environments, and should address both intentional and accidental reidentification risks throughout the AI development process.

A significant concern is the lack of a private right of action for individuals affected by healthcare data breaches, leaving many patients with limited recourse when their sensitive information is compromised. While many states have enacted laws more stringent than federal legislation, enforcement resources may be stretched thin.

Human Oversight and Professional Standards

In most federal and state regulatory schemes, ultimate responsibility for healthcare AI systems is assigned to the people and organizations that implement it rather than to the AI system itself. Healthcare providers must maintain ultimate authority for clinical decisions even when using AI-powered decision support tools. Healthcare AI applications must require meaningful human involvement in decision-making processes rather than defaulting to fully automated systems.

AI systems must provide healthcare providers with clear, easily accessible mechanisms to override algorithmic recommendations when clinical judgment suggests alternative approaches. Healthcare providers using AI systems must be provided with the tools to achieve system competency through ongoing training and education programs. At the organization level, hospitals and health systems must implement robust quality assurance programs that monitor AI system performance and healthcare provider usage patterns.

Medical schools and residency programs are beginning to incorporate AI literacy into their curricula, while professional societies are developing guidelines for the responsible use of these tools in clinical practice. For digital health developers, these shifts underscore the importance of designing AI systems that complement clinical workflows and support physician decision-making rather than attempting to automate complex clinical judgments.

The rapid advancement of AI in healthcare is reshaping certain medical specialties, particularly those that rely heavily on image interpretation and pattern recognition, such as radiology, pathology, and dermatology. As AI systems demonstrate increasing accuracy in reading X-rays, magnetic resonance images, and other diagnostic images, some medical students and physicians are reconsidering their specialization choices. This trend reflects broader concerns about the potential for AI to displace certain aspects of physician work, though most experts emphasize that AI tools should augment rather than replace clinical judgment.

Conclusion: Balancing Innovation and Responsibility

The healthcare AI landscape in the United States reflects the broader challenges of regulating rapidly evolving technologies while promoting innovation and protecting patient welfare. Despite regulatory uncertainties and implementation challenges, the fundamental value proposition of AI in healthcare remains compelling, offering the potential to improve diagnostic accuracy, enhance clinical efficiency, reduce costs, and expand access to specialized care.

Success in this environment requires healthcare organizations, technology developers, and regulatory bodies to maintain vigilance regarding compliance obligations while advocating for regulatory frameworks that protect patients without unnecessarily hindering innovation. Organizations that can navigate the complex and evolving regulatory environment while delivering demonstrable clinical value will continue to find opportunities for growth and impact in this dynamic sector.

The path forward demands a collaborative approach that brings together clinical expertise, technological innovation, regulatory insight, and ethical review. As 2025 progresses (and beyond), the healthcare AI community must work together to realize the technology’s full potential while maintaining the trust and confidence of patients, providers, and the broader healthcare system. This balanced approach will be essential to ensuring that AI fulfills its promise as a transformative force in American healthcare delivery.

Plunging over the Telehealth Cliff: Now What?

The telehealth cliff that we warned you about on March 3 and March 25, 2025, is now more fact than fiction—and we need a parachute.

Current Medicare telehealth flexibilities expired on September 30, 2025. This expiration has come to be called a “cliff,” since millions of beneficiaries who have used telehealth as a means for receiving health care services since the COVID-19 pandemic could lose coverage for this benefit. Now, they may have to travel to a health care provider’s office or a health care facility to receive most telehealth services, as opposed to simply logging on at home.

Without question, this is a move backward. Since restrictions for Medicare beneficiaries were eased at the start of the global pandemic in March 2020, many Americans—including seniors, those in rural areas, and those with mobility problems—have learned not only to use telehealth but to embrace it and in fact rely upon it.

“We are asking—urging—Congress to not leave millions of patients and beleaguered healthcare providers dangling on the telehealth cliff while they deliberate over dynamics around a government shutdown,” Kyle Zebley, senior vice president of public policy at the American Telehealth Association (ATA) and executive director of the organization’s advocacy arm, ATA Action, said on September 23.

ATA Action also urged Congress to ensure retroactive reimbursement of telehealth services in the event of a government shutdown. Since March, some never lost sight of the issue, while others may have assumed that Congress would step in and act, as it did in the last few expirations. But embroiled in a government shutdown, the September 30 deadline has come and gone. What happens now?

On October 1, 2025, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) released a special edition of its Medicare Learning Network (MLN) Connects, outlining how Medicare operations are being managed for claims, telehealth, and Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs) during the ongoing government shutdown. As part of this update, CMS instructed MACs to place a temporary hold, which can generally last up to 10 business days, on claim payments. The hold is designed to ensure payment accuracy and compliance with statutory requirements, while also avoiding the need to reprocess a high volume of claims if Congress approves government funding. During this time, providers can continue submitting claims, but payments will not be issued until the hold is lifted.

Flexibilities

The COVID-19 public health emergency officially came to an end in May 2023, but the Medicare telehealth flexibilities were extended piecemeal as each subsequent extension ran out. The American Relief Act of 2025, passed in December 2024, created a 90-day extension of the Act through March 2025, in Section 3207. A House and Senate Continuing Resolution (CR) enacted on March 15 extended the telehealth flexibilities through September 30, 2025.

Section 2207 of the CR, “Extension of Certain Telehealth Flexibilities,” was substantively identical to Section 3207 of the American Relief Act (granting the extension for telehealth flexibilities through March 2025). So until September 30, this meant:

THEN: Geographic requirements were removed for telehealth services, and originating sites were expanded, by amending Section 1834(m) of the Social Security Act, 42 U.S.C. 1395m(m) (entitled “Payment for Telehealth Services”) (“the Act”).