UK ICO Launches Review of Children’s Privacy in Mobile Gaming

On December 1, 2025, the UK Information Commissioner’s Office (“ICO”) announced a new initiative to scrutinize privacy protections in mobile games frequently played by children in the UK. As digital gaming continues to grow in popularity among children, the review by the ICO signals renewed regulatory attention as to how mobile gaming platforms safeguard personal data of young users.

The ICO will conduct a monitoring program focusing on 10 mobile games widely used by children. The assessment will center on three critical areas:

Default Privacy Settings: Evaluating whether games are configured to protect children’s privacy from the outset.

Geolocation Controls: Scrutinizing how games handle location data and whether children’s whereabouts are adequately protected.

Targeted Advertising: Reviewing practices around serving targeted ads to children.

In addition to these core areas, the ICO’s review will consider any other privacy risks that emerge during the process.

This latest focus follows the ICO’s Children’s code strategy, which has previously led to significant improvements in children’s privacy standards on social media and video-sharing platforms.

Read the UK ICO press release here.

CNIPA November 2025 Press Conference: More Details on Examination of AI Patents and the Chinese IP Firm Rectification Campaign

On November 28, 2025, China’s National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) held a press conference that provided more details about the recently revised Guidelines for Patent Examination for Artificial Intelligence (AI) and the recently announced Rectification Campaign on IP firms and IP practitioners that includes the Ministry of Public Security. Excerpts follow.

Regarding the Examination Guidelines:

Q: Lizhi News Reporter:

Director Jiang just mentioned that the recent revisions to the Patent Examination Guidelines further improve the examination standards for patent applications in the field of artificial intelligence. We have noticed that the Guidelines have been revised in several recent revisions, all of which have addressed related content. What is the relationship between this revision and previous revisions? What is the specific significance of these adjustments and changes?

A: Jiang Tong, Director of the Examination Business Management Department of the Patent Office

Thank you for your question. Accelerating the development of next-generation artificial intelligence is a strategic issue concerning whether my country can seize the opportunities presented by the new round of technological revolution and industrial transformation. Intellectual property plays a crucial dual role in serving the development of the artificial intelligence industry, providing both institutional and technological support. To promptly respond to the urgent needs of innovation entities for the protection of AI-related technologies, we have revised and improved the examination standards for patent applications in the field of artificial intelligence three times, and clarified them in the “Patent Examination Guidelines.”

The 2019 revision added a dedicated chapter on algorithmic features and clarified the standards for examining the subject matter eligibility, novelty, and inventiveness. The 2023 revision clarified the standards for examining the subject matter eligibility of artificial intelligence and big data, enriched the types of protectable topics, and for the first time introduced “user experience enhancement” as a factor in assessing inventiveness. This revision further improves the examination standards in the field of artificial intelligence, establishing a dedicated chapter for “artificial intelligence and big data” for the first time, mainly including three aspects:

First, we must strengthen ethical review of artificial intelligence. We should enhance the role of policy and legal safeguards, and in accordance with Article 5 of the Patent Law, which addresses the legality and ethical requirements of patent authorization, clarify that the implementation of AI-related technical solutions such as data collection and rule setting should comply with legal, social, and public interest requirements, thus solidifying the safety bottom line and guiding the development of AI towards “intelligent good.”

Second, the requirements for disclosing technical solutions in application documents are clarified. Addressing the “black box” nature of artificial intelligence models—that is, the public only knows the model’s inputs and outputs but not the logical relationship between them—and the potential problem of insufficient disclosure of technical solutions, the requirements for writing detailed descriptions in scenarios such as model construction and training are clarified, and the criteria for judging full disclosure are refined, thereby promoting the dissemination and application of artificial intelligence technologies.

Third, improve the rules for judging inventiveness. Clarify the inventiveness review standards for artificial intelligence technologies in different application scenarios and for different objects of processing, and use case studies to illustrate how to consider the contribution of algorithmic features to the technical solution, so as to further improve the objectivity and predictability of the review conclusions.

Going forward, we will continue to track the development of emerging industries and new business models such as artificial intelligence, and continue to improve our review standards in a timely manner to better adapt to the needs of technological development, providing a solid institutional guarantee for supporting the national strategic emerging industries layout and serving high-level scientific and technological self-reliance. Thank you.

Regarding the Rectification Campaign

Q: China Intellectual Property News Reporter:

Recently, the CNIPA, the Ministry of Public Security, and the State Administration for Market Regulation jointly launched a special campaign to rectify the intellectual property agency industry. What is the background to this special campaign? What are the main rectification measures to be taken?

A: Wang Peizhang, Director of the Department of Intellectual Property Utilization and Promotion

Thank you for your question. The intellectual property agency industry is a core component of the intellectual property service industry. High-quality agency services are crucial for achieving high-quality creation, efficient utilization, and high-standard protection of intellectual property. In recent years, the intellectual property agency industry has continued to develop and its service level has been continuously improving, making significant contributions to building a strong intellectual property nation. However, driven by profit, illegal and irregular activities in the intellectual property agency industry have also become increasingly frequent, seriously damaging the legitimate rights and interests of innovation entities, disrupting normal market order, and hindering the healthy development of the intellectual property cause. In response, the CNIPA attaches great importance to this issue and, in conjunction with the Ministry of Public Security and the State Administration for Market Regulation, has launched a three-month special rectification campaign.

This special rectification campaign adheres to the principles of problem-oriented approach, addressing both symptoms and root causes, implementing differentiated policies, and striving for practical results. It deploys 14 tasks across three aspects: severely cracking down on illegal and irregular activities, focusing on rectifying non-standard professional practices, and strengthening source governance. First, it severely cracks down on seven prominent illegal agency behaviors, including falsifying patent applicant information, fabricating patent applications, acting as an agent for a large number of abnormal patent applications, engaging in fraud, acting as an agent for malicious trademark applications, acting as an unqualified patent agent, and soliciting agency business through improper means. It also strengthens the connection between administrative and criminal law, transferring cases constituting crimes to public security organs for legal prosecution. Second, it focuses on rectifying the practice of agencies and personnel renting or lending their qualifications, accelerating the cleanup of agencies that have obtained agency qualifications through fraudulent means or no longer meet the conditions for practicing, and promoting the streamlining and improvement of the industry. Third, it comprehensively regulates the application, transfer, and operation behaviors of three types of entities: innovation entities, intellectual property buyers, and transaction operation platforms, and accelerates the optimization and adjustment of various assessment and evaluation policies related to patents. By strictly investigating and punishing illegal patent agencies and practitioners, rectifying and eliminating irregular practices, and publicly exposing typical illegal cases, a rapid deterrent effect is achieved. Simultaneously, the campaign emphasizes coordinated efforts from the application, examination, and agency ends to combat improper patent trading, curbing patent applications not based on genuine invention and patent trading not aimed at industrialization at the source. Overall, this special rectification campaign is not only a precise rectification of the problems exposed in the industry but also a powerful impetus for the long-term healthy development of the industry.

Next, we will strengthen organization and implementation, intensify rectification efforts, deepen source governance, and improve publicity and guidance to ensure that the rectification work achieves tangible results, promote the development of the intellectual property agency industry through standardization and improvement, and provide strong support for the high-quality development of the intellectual property cause. Thank you.

A full transcript of the press conference is available here (Chinese only).

Seeking Grace- Pursuing Method of Treatment Claims in View of Clinical Trial Related Disclosures

I. Background

Method of treatment patents based on Phase II and Phase III clinical trial protocols are routinely pursued to extend patent exclusivity and strategically build a patent portfolio for a drug asset. The claims of these “later-generation” method of treatment patents recite salient features of the Phase II or Phase III clinical trial protocol including patient populations, dosage amounts, dosing regimens, and efficacy outcome measurements. This is done for good reason, as the salient features of the study protocol often appear on the drug label, sometimes as part of explicit active steps.

For a new chemical entity (NCE), a later-generation method of treatment patent provides additional patent term, sometimes years beyond the patent term of the earlier-generation patents, i.e., foundational patents providing composition of matter and/or broad method of treatment exclusivity.

For repurposed drugs or novel dosing protocols, method of treatment patents based on Phase II or Phase III clinical trial study protocols may provide the only meaningful source of patent exclusivity, e.g., if the compound is known and the composition of matter patent has expired or is soon to expire.

Conventional wisdom dictates filing a patent application based on a Phase II or Phase III clinical trial protocol prior to a public disclosure of the study to avoid creation of prior art that can preclude patentability of the method of treatment claims, particularly outside the U.S.[1] Given the strategic importance of later-generation method of treatment patents, care should be taken to understand the timing of any public disclosures relating to the clinical trial and to plan patent application filings accordingly.

One such clinical trial related public disclosure is the posting of the innovator’s clinical trial protocol to ClinicalTrials.gov (“CTG”) as a so-called “study record.”[2] Posting of the study record is part of the U.S.’s well-intentioned effort to conduct human clinical trials with transparency to, inter alia, build public trust in clinical research and help patients find trials for which they might be eligible to participate. Innovators are to submit clinical trial study protocols to FDA no later than 21 days after the first patient is enrolled in the trial[3], and the study record will be posted not later than 30 days after submission[4][5]. Given these deadlines, it is typically not possible to predict the exact day a study record becomes public on CTG. Such an “un-docketable” deadline, unlike the firm date of an expected journal article publication or public symposium, has – perhaps unsurprisingly – led to a fact pattern where a study record is posted to CTG before a corresponding method of treatment patent application is filed.

II. Use of the § 102(b)(1)(A) exception

Clinical trials themselves are not considered a prior public use under 35 U.S.C. § 102(a)(1).[6] CTG study records and other clinical trial related disclosures, however, are considered printed publications and/or “otherwise available to the public” under §§ 102(a)(1) if made before the effective filing date of the patent application. Such clinical trial related disclosures can therefore be used to reject a later-filed patent application’s method of treatment claims as anticipated under 35 U.S.C. § 102(a)(1) and/or obvious under 35 U.S.C. § 103.

In the event a CTG study record or related disclosure becomes publicly available prior to filing a corresponding U.S. method of treatment patent application, the grace period exception under § 102(b)(1)(A) may be invoked to disqualify the disclosure under § 102(a)(1) – provided the disclosure is made one year or less before the effective filing date of the application. Procedurally, should an Examiner make a rejection under 35 U.S.C. §§ 102(a)(1) and/or 103 based on a CTG study record or related disclosure, Applicant can invoke the grace period by submitting a declaration under 37 CFR § 1.130 (“Rule 130”) establishing that the disclosure was made by the inventor or joint inventors and requesting removal of the CTG study record or related disclosure as prior art.

While submission of the Rule 130 declaration seems straightforward, a recent PTAB example, Murray & Poole Enterprises Ltd. v. Institut de Cardiologie de Montreal[7] is illustrative of potential traps. Institut de Cardiologie de Montreal (ICM) attempted to remove “Bouabdallaoui” as prior art by invoking the grace period exception under § 102(b)(1)(A). Bouabdallaoui was published within the one-year grace period and expanded on the results of the “COLCOT” CTG study record. Bouabdallaoui listed seven authors, the second of whom, Dr. Tardif, was the sole inventor on ICM’s patent. The board articulated that invocation of the grace period hinged on whether the declaration of Dr. Tardif provided sufficient information to conclude that Bouabdallaoui was not “by another.”[8] Dr. Tardif’s declaration explained the working relationship with only one co-author (Bouabdallaoui), as inter alia, acknowledgement of Bouabdallaoui’s assistance in conducting the clinical trial and to provide a first author publication. Dr. Tardif’s declaration also described the scope of the COLCOT multi-center clinical trial and ICM’s status as the sponsor, supported by agreements between some of the centers and the sponsor. The board pointed out that only a subset of center-sponsor agreements was provided and, among the agreements provided, none listed Dr. Tardif as the principal investigator.[9] Ultimately, in its decision of institution, the board found that Dr. Tardif’s declaration was insufficient to disqualify Bouabdallaoui as prior art.[10]

As Murray demonstrates, all differences between the authors of the clinical trial related disclosure and inventors on the patent application should be thoroughly explained. Declarations from any superfluous authors, i.e., non-inventors, disclaiming their contribution to the subject matter relied on in making the prior art rejection may help establish that the clinical trial related disclosure is not “by another.” CTG study records, unlike typical publications, list only the sponsor of a clinical trial, not specific individuals responsible for designing the study. Nonetheless, the inventor(s) can attest to the CTG study record as their own work in a declaration. Supporting documentation clearly tying the inventor(s) to the CTG study record, e.g., by naming the inventor(s) as the principal investigator(s), can also be provided.

III. International grace period provisions and filing strategies

In addition to the U.S., several foreign jurisdictions also provide a grace period. While not exhaustive, Table 1 summarizes grace period availability in commonly filed foreign jurisdictions, application filing timing, and whether proactive steps should be taken to make use of the grace period. Practitioners should work closely with local counsel to understand nuanced national requirements and timing to properly rely on each country’s available grace period.

Table 1

Country

Grace Period Available

Time to file application (from disclosure)

Type of first application that should be filed

Can the first application serve as priority document…†

Notes

AU

Yes

12 months

AU Standard Application or PCT

Yes (for PCT)

No proactive steps required.

BR

Yes

12 months

U.S. Provisional, BR, or PCT

Yes

No proactive steps required.

CA

Yes

12 months

CA or PCT

No

No proactive steps required.

CN

No

—

—

CTG disclosure does not qualify for the grace period.

EP

No

—

—

CTG disclosure does not qualify for the grace period.

JP

Yes

12 months

JP or PCT

No

Within 30 days of filing the JP national application or JP national phase entry, a certificate must be filed describing several features of the public disclosure.

KR

Yes

12 months

KR or PCT

Yes, but only if priority filing is (a) a PCT application designating only KR or (b) a direct KR application

Evidentiary documents must be submitted proving the applicant/inventor’s disclosure and showing (i) the date and type of the disclosure, (ii) the disclosing party, and (iii) the content of the disclosure.

MX

Yes

12 months

U.S. Provisional, MX, or PCT

Yes

The date of the public disclosure must be included on a form when filing the MX national application or MX national phase entry of the PCT.

PH

Yes

12 months

U.S. Provisional, PH, or PCT

Yes

No proactive steps required.

SG

Yes

12 months

PCT

No

No proactive steps required.

TW

Yes

12 months

TW

No

No proactive steps required.

U.S.

Yes

12 months

U.S. Provisional or PCT

Yes

No proactive steps required.

† for a PCT or other application filed after the grace period that benefits from the grace period?

Like the U.S., Australia, Brazil, Canada, Japan, Mexico, the Philippines, South Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan all provide grace periods for CTG study records and related disclosures within 12 months of a first patent application’s filing date. They differ, however, with respect to whether the first patent application can serve as a priority document to a later-filed application, e.g., a PCT application, where the national stage application of the PCT application will also be eligible to benefit from the grace period. Certain jurisdictions, e.g., China and Europe, effectively do not have grace periods applicable to CTG study records or related disclosures.

In view of these distinctions, one can envisage complex potential filing strategies depending on international filing priorities.

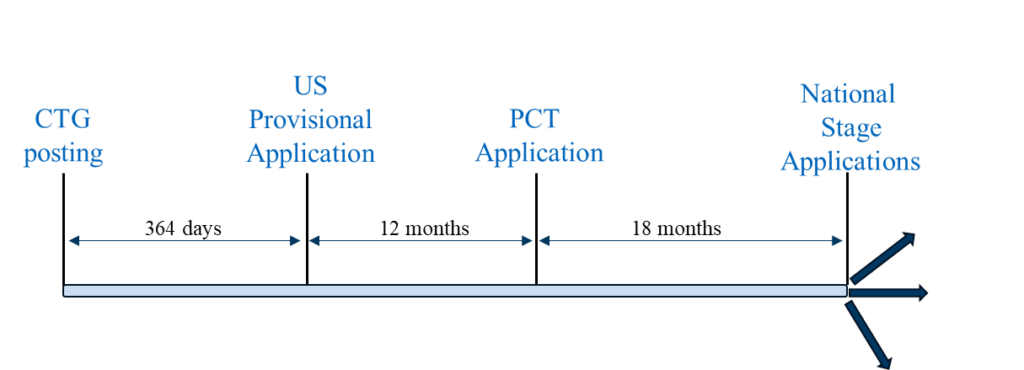

Scenario 1 is a “typical” filing strategy where a U.S. provisional application is the first-filed application in the family. This filing strategy can be followed to pursue patent coverage in countries where a U.S. provisional application filed within 12 months of the CTG study record or related disclosure can serve as a priority document to a PCT application filed 12 months after the U.S. provisional application, and the national phase applications of the PCT application are eligible to benefit from the grace period based on the U.S. provisional application’s filing date. Representative countries in which this filing strategy can be utilized include the U.S., Brazil, Mexico, and the Philippines.

Filing Scenario 1

Scenario 1 can also be followed in countries that actually or effectively lack grace periods (e.g., China and Europe). To overcome the absolute novelty bar in China, possible aspects of the planned commercial methods that are not disclosed in the clinical trial related disclosure can be included in the U.S. provisional and/or PCT application. In Europe, CTG study records or announcements regarding ongoing trials not considered to be novelty destroying, although they can be used in an inventive step analysis.[11] For guidance on the implications of clinical trials as prior art in Europe, we direct the reader to the Spring 2024 AIPLA Chemical Practice Committee’s informative article on this very topic.[12]

Scenario 2 can be followed in countries where a PCT or non-PCT country national application must be filed within one year of the public disclosure for the national application to be eligible to benefit from a grace period. Representative countries in which this strategy can be utilized include Australia, Canada, Japan, Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan.

Filing Scenario 2

Scenario 1 provides two potential advantages compared to (a) a more conservative filing strategy where the U.S. provisional application is filed prior to the CTG study record posting and (b) Scenario 2: (1) maximum time for generating clinical trial results which, if available, can be included in the PCT application, and (2) the potential for maximum patent term.

Scenario 2 does not offer the benefit of an extended duration between CTG study record posting and national or PCT application filing. As such, results of the clinical trial are generally less likely to be available by the time a PCT application or non-PCT country national application is filed. However, many of the above-mentioned countries permit post-filing data during prosecution by which clinical trial results can be presented.[13]

Scenario 3 combines Scenario 1 and Scenario 2 into a unified filing strategy. First, a U.S. provisional application (following Scenario 1), a first PCT application (PCT1) (following Scenario 2), and non-PCT country national application(s) (following Scenario 2) are filed on the same day and within one year of the CTG study record posting. Prior to filing any applications outside the U.S., a foreign filing license should be considered and, if necessary, obtained. PCT1 can be nationalized in the jurisdictions with stricter grace period requirements outlined above for Scenario 2.

Filing Scenario 3

A second PCT application (PCT2) claiming priority to the U.S. provisional application can then be filed on the 12-month Convention date for the U.S. provisional application that includes the results of the clinical trial, if available. PCT2 can be nationalized in the jurisdictions with more relaxed grace period requirements as outlined above for Scenario 1.

This bespoke approach maximizes the potential benefits of grace periods, where available, while accounting for inclusion of clinical trial results data (either in PCT2 or as post-filing data during national stage application prosecution). The result is improved chances of obtaining method of treatment coverage and longer patent term.

IV. Conclusion

CTG posting of a Phase II or Phase III study record or a related public disclosure does not inevitably preclude patentability of method of treatment claims in a later-filed patent application based on the clinical trial protocol. A surprising number of jurisdictions provide grace periods by which a CTG study record or related disclosure can be removed as prior art if a patent application is filed within one year of the disclosure. However, the type of patent application that must be filed within one year varies by jurisdiction, thereby leading to complex filing strategies. In the U.S., to exclude CTG study records using the § 102(b)(1)(A) exception, practitioners should carefully draft Rule 130 declarations that unambiguously tie the inventor(s) of the patent application to the sponsor and principal investigator(s) of the clinical trial. Similarly, Rule 130 declarations to exclude clinical trial related disclosures using the § 102(b)(1)(A) exception should unambiguously explain any and all differences between the author(s) of the disclosure and the inventor(s) of the claimed subject matter.

[1] Most ex-US jurisdictions do not permit “method of treatment” claims per se, although such claims can be reformulated in accordance with local practice, e.g., as Swiss-type claims and/or purpose-limited compounds for use-type claims.

[2] 42 U.S.C. § 282(j)(2)(A)

[3] 42 U.S.C. § 282(j)(2)(C)

[4] 42 U.S.C. § 282(j)(2)(D)

[5] Changes to the clinical trial, including changes to the protocol, are also posted to CTG by the same mechanism such that multiple study records are typically available on CTG for a given clinical trial.

[6] See, e.g., Sanofi v. Glenmark Pharms, Inc., USA, 204 F. Supp. 3d 665 (D. Del. 2016), aff’d sub nom., Sanofi v. Watson Lab’ys Inc., 875 F.3d 636 (Fed. Cir. 2017) (A patent on a method of using dronedarone in treating patients was not ready for patenting before the critical date and thus not a public use); In Re Omeprazole Patent Litigation, 536 F.3d 1361 (Fed. Cir. 2008) (A Phase III clinical trial was not a public use because the invention had not been reduced to practice and therefore was not ready for patenting).

[7] IPR2023-01064, Paper 9 (P.T.A.B., Jan. 16, 2024).

[8] Id., page 54.

[9] Id., page 55.

[10] Id., page 56.

[11] T 158/96, T 715/03, T 1859/08 and T 2506/12

[12] Dr. Holger Tostmann, Newsletter of the AIPLA Chemical Practice Committee, Spring 2024, Volume 12, Issue I, p. 24.

[13] In Canada, utility is established by demonstration or “sound prediction” at the time the application is filed.

Adopting an “Orphan Works” Scheme: Proposals from the Copyright Amendment Bill 2025 (Cth)

The Federal Government recently announced Australia’s first statutory orphan works scheme by way of the Copyright Amendment Bill 2025 (Cth) (Bill).

Orphan works refer to copyright materials for which the owner cannot be identified or located. The policy considerations on orphan works are discussed at length in an earlier blog post, Proposed Copyright Reform in Australia – Limited Liability Scheme for Use of Orphan Works.

The Bill also clarifies the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) (Act) to permit use of copyright materials by schools in online teaching environments, as well as outlining other minor technical amendments to the Act.

Reasonably Diligent Searches

The Bill adds Division 2AAA to the Act, which limits the remedies available to copyright owners for copyright infringement if an owner could be identified or located at the time of infringement. Specifically, the Court cannot grant relief against an alleged infringer if:

They conducted a “reasonably diligent search” for the copyright owner;

The search was conducted within a reasonable period before the infringing use;

They maintained a record of the search;

The copyright owner could not be identified or located at the time of the infringing use and therefore permission could not be obtained; and

A clear and reasonably prominent notice was given in relation to the infringing use, stating that:

The copyright owner could not be located or identified; and

The orphan works scheme applies.

On the point of “reasonably diligent” searches, the Explanatory Memorandum explained:

Higher standards of search would be reasonably expected for types of material and uses that present a higher level of risk to rights holder interests, such as commercial uses, more vulnerable materials (including photographs and images) and culturally sensitive materials. Higher standards of search may also be required if the work is a foreign work and the copyright owner is likely to be residing overseas.

Implications of the Scheme

If a copyright owner is identified or located after allegedly infringing use, the scheme will allow the rights holder to seek reasonable payment for past use and for the parties to negotiate terms for continuing use. The scheme also empowers the Courts to set reasonable terms for continuing use or to provide injunctive relief.

However, it is explicitly stated that the scheme is not intended to support large-scale uses of orphan works for training large language models or other generative AI. Instead, the reasonable diligence conditions are likely to be too “administratively burdensome, time consuming and impractical”.1

Overall, the proposed orphan works scheme will provide copyright users with greater legal certainty and increased access to a larger collection of cultural, historical and educational works. Rights holders may also earn new income from works that have been unknowingly or unintentionally orphaned, but with which they are reunited as the owner through the diligent search requirements.

What Happens Next?

The Bill has been referred to the Legal and Constitutional Affairs Legislation Committee for inquiry, and the committee’s report is due on 19 December 2025.

A Recent Change In Patent Office Procedures Makes Challenging Patents More Difficult

Retail and consumer products companies in the United States face a constant threat of patent infringement lawsuits and—for reasons described herein—that threat could soon increase. These lawsuits can be costly and disruptive, exposing companies to significant legal fees, discovery expenses, and the risk of large damages awards or injunctions.

In 2011, Congress enacted the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act (AIA), providing accused infringers with a way to challenge the validity of issued patents, called inter partes review (IPR). The stated intent behind the creation of the IPR process was to improve patent quality by providing a faster, less expensive, and more efficient administrative alternative to federal court litigation for challenging patent validity. As part of this process, the AIA created the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), a tribunal within the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), to handle IPRs.

Companies facing infringement lawsuits quickly saw many benefits of the IPR process. The costs of an IPR were far less than litigating a patent case to final judgment in federal court, and the standard of proof for invalidating a patent in an IPR proceeding was much lower than in federal court (preponderance of the evidence versus a clear and convincing standard). In addition, many district courts would agree to stay patent lawsuits while IPRs were pending, leading to even greater cost savings. The success rate for instituted IPR proceedings has been overwhelmingly favorable to patent challengers, with nearly 80% of challenged claims being found invalid when the PTAB issued a final written decision.

The AIA provides that an IPR may not be instituted unless the petition “shows there is a reasonable likelihood that the petitioner would prevail with respect to at least one of the claims challenged in the petition.” This provision has been interpreted to provide the Director of the USPTO with complete discretion to deny institution.

Historically, the Director delegated this authority to the PTAB; the PTAB would assess the merits of an IPR petition and institute an IPR proceeding in more than 60% of the cases. However, beginning in 2020, the PTAB started considering non-merits factors and increasingly exercising its discretion to deny institution of IPRs.

In April 2025, the interim Director of the USPTO revoked the delegation of authority to consider discretionary issues from the PTAB, and restored that authority with the Director. By mid-2025, the IPR institution rate had dropped to approximately 35%. After the new permanent Director was confirmed in September 2025, he further consolidated power and issued a memorandum stating that the Director would make all IPR institution determinations in summary fashion without providing any supporting reasoning.

Under the new procedures, the IPR institution denial rate is now near 100%. Industry groups, including the National Retail Federation, have sent letters to government officials opposing these changes, and unsuccessful IPR petitioners have filed mandamus challenges, but, thus far, those efforts have not altered the USPTO’s policies.

In light of these changes, we expect to see an uptick in patent litigation against retail and consumer products companies, as patent owners become less fearful of IPR challenges.

However, there is another defensive strategy. Accused infringers should consider the ex parte reexamination (EPR) process as an alternative to IPRs, which will become less advantageous. The EPR process was established in 1981 and allows for a post-grant review of validity before the USPTO.

EPRs offer some of the benefits of IPRs, but also come with some disadvantages. On the plus side, EPRs are not subject to any discretionary denial risk, leading to a near 95% grant rate. EPRs typically cost a fraction of an IPR, largely because, once filed, the requester no longer participates in the process. And like IPRs, an EPR proceeding can lead to a stay of district court litigation, although the stay rate is lower for EPRs because the EPR process takes longer. On the other hand, EPRs have a lower successful rate of invalidation, and provide the patent owner with the opportunity to amend the patent claims during the process, which can impact litigation strategy.

In light of this quickly changing landscape, retail and consumer products companies facing patent infringement claims should discuss with their patent counsel the pros and cons of these two administrative patent challenge processes early in any litigation for the best chance for success.

Claim Construction: Indefinite or Clerical Error?

This Federal Circuit opinion analyzes the “very demanding standard” of judicial correction of erroneous wording of a patent claim.

Background

Canatex Completion Solutions owns U.S. Patent No. 10,794,122. This patent covers a releasable connection device for a downhole tool string used during downhole operations in oil and gas wells. The device has two parts locked together. In circumstances where the further downhole (first) part of the device has gotten stuck, the operator can disconnect the two parts of the device, leaving the further downhole (first) part in the well while pulling the upper (second) part to the surface.

Canatex accused Wellmatics, LLC, GR Energy Services, LLC, GR Energy Services Management, LP, GR Energy Services Operating GP, LLC, and GR Wireline, L.P. (collectively, “Defendants”) of infringing the ’122 patent in the District Court for the Southern District of Texas. In response, Defendants challenged the ’122 patent’s validity. The claimed phrase at issue was “the connection profile of the second part.” Defendants argued the claims that included this phrase were indefinite for lack of an antecedent basis, while Canatex argued the phrase contains an evident error and that the intended meaning was “the connection profile of the first part.”

The district court agreed with Defendants that the claims were indefinite, ruling that “the error” identified by Canatex “is not evident from the face of the patent and the correction to the claim is not as simple as [Canatex] makes it seem.” In fact, the court ruled this “error” “was an intentional drafting choice and not an error at all.” The court further concluded that Canatex’s failure to seek correction from the USPTO pursuant to 35 U.S.C. § 255, which expressly permits the USPTO to correct certain clerical, typographical, and minor errors, suggested that the error is neither minor nor evident on the face of the patent.

Canatex appealed to the Federal Circuit, challenging as legally erroneous the district court’s determinations that (i) no error in the claim phrase at issue was evident on its face of the patent and (ii) there was no unique evident correction.

Issues

Whether it is evident on the face of the ’122 patent that the claim language at issue contains an error.

Whether Canatex’s correction of “second” to “first” is the unique correction that captures the claim scope a reasonable relevant reader would understand was meant based on the claim language and specification.

Holdings

Yes. It is evident on the face of the ’122 patent that the claim language at issue contains an error.

Yes. The correction of “second” to “first” is the unique correction that captures the claim scope a reasonable relevant reader would understand was meant based on the claim language and specification.

Reasoning

Error evident on the face of the ’122 patent. The Federal Circuit reasoned that a relevant artisan would immediately see that, as written, there is an error in the claim. The phrase at issue plainly requires an antecedent (“the connection profile of the second part”), but no “connection profile of the second part” is previously recited in the claim. In addition, the Federal Circuit reasoned that the reference to a nowhere-identified “connection profile of the second part” “makes no sense” given the claim language. Further, the Federal Circuit reasoned this error was evident in view of the patent specification. Regarding Canatex’s failure to seek correction from the USPTO, the Federal Circuit distinguished between a correction made by the PTO under § 255, which is only made as prospective (i.e., going forwards), and a judicial correction, which determines the meaning the claim has always had.

The unique correction. The Federal Circuit reasoned that the only reasonable correction was to change “second” to “first” in the claim language. This was what the claim language as a whole required. Further, the specification showed that the patentee plainly meant the connection profile of the first part. Nothing in the prosecution history suggested otherwise. The Federal Circuit rejected Defendants’ arguments that there are other reasonable corrections, reasoning that Defendants’ alternative corrections were either unavailing or inconsistent with the claim’s meaning.

Conclusion

The Federal Circuit reversed and remanded. The Federal Circuit concluded that it is evident the claim contains an error and that a relevant artisan would recognize that there is only one correction that is reasonable given the intrinsic evidence. Although the Federal Circuit recognized a judicial correction to claim language in this case, this opinion nevertheless highlights “the very demanding standards for judicial correction of a claim term” and that such corrections are only “proper in narrow circumstances.”

Ninth Circuit Refuses to Apply California’s “Reasonable Particularity” Requirement to Claims Under the Defend Trade Secrets Act

The Ninth Circuit’s recent decision in Quintara Biosciences, Inc. v. Ruifeng Biztech, Inc. underscores an important distinction in trade secret law between California’s Uniform Trade Secrets Act (“CUTSA”) [Cal. Civ. Code, §§ 3426 et seq.] and the federal Defend Trade Secrets Act (“DTSA”) [18 U.S.C.A. §§ 1832 et seq.]. Specifically, the Court’s reasoning clarifies when and how plaintiffs must identify their alleged trade secrets under each regime.

Quintara Biosciences (“Quintara”), a DNA sequencing analysis company, alleged that Ruifeng Biztech (“Ruifeng”) misappropriated nine of Quintara’s trade secrets, ranging from databases and marketing plans to specialized protocols and software code. Quintara brought suit in the United States District Court for the Northern District of California.

At the Rule 26(f) discovery planning conference, Ruifeng sought to compel Quintara to identify its trade secrets with “reasonable particularity” before discovery could proceed as required by Section 2019.210 of the CUTSA. See C.C.P. § 2019.210 (“before commencing discovery relating to the trade secret, the party alleging the misappropriation shall identify the trade secret with reasonable particularity”). The district court agreed and ordered Quintara to do so before discovery could commence. Quintara later amended its trade secret identification to add even more detail but Ruifeng, still dissatisfied, filed a Rule 12(f) motion to strike.

While the district court acknowledged that “state procedure does not govern here,” it nonetheless applied the CUTSA reasonable particularity standard. Finding that all but two of Quintara’s trade secrets failed to satisfy the CUTSA’s threshold, the district court struck those trade secrets. After losing at trial, Quintara appealed.

On appeal, the Ninth Circuit reversed the order striking Quintara’s trade secrets. The opinion drew key distinctions between the DTSA and the CUTSA. In particular, while the CUTSA requires plaintiffs to identify their trade secrets with “reasonable particularity” before discovery can proceed, the DTSA only requires identification of a trade secret with “sufficient particularity” in order for that claim to survive summary judgment. The Ninth Circuit held that the district court’s reliance “on a California rule that does not control a federal trade-secret claim” to strike Quintara’s trade secrets constituted an abuse of discretion.

Quintara makes clear that the DTSA and the CUTSA impose different procedural hurdles for plaintiffs. In federal court under the DTSA, litigants enjoy greater initial flexibility but must ultimately refine and substantiate their claims with “sufficient particularity” to survive a motion for summary judgment. In contrast, plaintiffs pursuing CUTSA claims in California state court must identify their trade secrets with “reasonable particularity” before discovery can even commence.

USPTO’s Revised Inventorship Guidance for AI-Assisted Inventions- What Changed, What Stayed, and What Practitioners Should Do Now

The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has issued updated examination guidance (“New Guidance”) on inventorship in applications involving artificial intelligence (AI). The document rescinds and replaces the February 13, 2024 guidance and clarifies how inventorship should be determined when AI is used in the inventive process. The New Guidance jettisons the Pannu test for this purpose, which focused on joint inventorship issues, and instead focuses on conception. This action is another step by the new USPTO leadership to bolster the patent system. It remains to be seen whether the courts will agree with this approach. It is possible that some patents will be granted by the USPTO under this guidance but be found invalid by the courts. This will remain highly fact dependent. Below is a detailed breakdown of the key changes and practical implications for patent strategy across utility, design, and plant filings.

The Big Reset: Prior AI Inventorship Guidance Withdrawn

The USPTO expressly rescinds the February 13, 2024 “Inventorship Guidance for AI-Assisted Inventions” in its entirety and withdraws its application of the Pannu joint inventorship factors to AI-assisted inventions as a general inventorship framework. The Office emphasizes that Pannu was and remains a doctrine to determine joint inventorship among multiple natural persons; it does not apply where the only other “participant” is an AI system, which by definition is not a person. In short, the prior approach is off the table, and the agency has refocused the analysis on traditional legal principles of conception and inventorship.

No “Joint Inventor” Question When AI Is the Only Other Actor

The New Guidance squarely states that when a single natural person uses AI during development, the joint inventorship inquiry does not arise because AI systems are not “persons” and therefore cannot be joint inventors. This resolves prior confusion over whether to run a joint-inventorship analysis in single-human-plus-AI scenarios; the answer is no. The presence of AI tools does not, by itself, trigger multi-inventor analysis.

One Uniform Standard: Traditional Conception Governs AI-Assisted Work

The USPTO underscores that the legal standard for inventorship is the same for all inventions—there is no separate or modified standard for AI-assisted inventions. Only natural persons can be inventors under Federal Circuit precedent. Accordingly, AI—regardless of sophistication—cannot be named as an inventor or joint inventor. The touchstone of inventorship remains “conception,” defined as the formation in the inventor’s mind of a definite and permanent idea of the complete and operative invention. Conception requires a specific, settled idea and a particular solution to the problem at hand; a general goal or research plan is insufficient.

Conception Requires Particularity and Possession

The New Guidance reiterates that inventorship is a highly fact-intensive inquiry focused on whether the inventor possessed knowledge of all limitations of the claimed invention such that only ordinary skill would be necessary to reduce it to practice, without extensive research or experimentation. The analysis turns on the ability to describe the invention with particularity; absent such a description, an inventor cannot objectively substantiate possession of a complete mental picture. This framing reinforces the benefit of robust, contemporaneous documentation of the inventor’s mental steps and the concrete claims that flow from them—especially when AI has been used to generate or refine inputs that inform the claimed features.

AI as a Tool: Presumptions, Naming Practices, and Rejections

As a practical matter, the USPTO maintains its presumption that inventors named on the application data sheet or oath/declaration are the actual inventors. However, the Office instructs that a rejection under 35 U.S.C. §§ 101 and 115 (or other appropriate action) should be applied to all claims in any application that lists an AI system or other non-natural person as an inventor or joint inventor. Conceptually, AI systems—including generative AI and computational models—are “instruments” used by human inventors, analogous to laboratory equipment, software, and databases. Inventors may use the “services, ideas, and aid of others” without those sources becoming co-inventors; the same principle applies to AI systems. When a single natural person is involved, the only question is whether that person conceived the invention under the traditional conception standard.

Multiple Human Contributors: Joint Inventorship Still Uses Pannu

When multiple natural persons are involved in creating an invention with AI assistance, traditional joint inventorship principles, including the Pannu factors, apply to determine whether each person qualifies as a joint inventor. Each purported inventor must: (1) contribute in some significant manner to the conception or reduction to practice; (2) make a contribution that is not insignificant in quality relative to the full invention; and (3) do more than merely explain well-known concepts or the current state of the art. Importantly, the mere involvement of AI tools does not alter the joint inventorship analysis among human contributors. Practitioners should evaluate and document each human’s inventive contribution against the claims, as usual.

Beyond Utility: Design and Plant Patents Are Covered

The New Guidance confirms that the same inventorship inquiry applies to design patents and utility patents. For plant patents, the statute and Federal Circuit precedent require that the inventor contributed to the creation of the plant (not just discovered and asexually reproduced it). The USPTO clarifies that these principles apply equally when AI assists the development of designs or plant varieties. As a result, applicants should treat AI involvement as they would any other tool across all patent types—demonstrating human conception and contribution consistent with the governing statutes and case law.

Priority and Benefit Claims: Inventor Identity Must Align

For applications and patents claiming benefit or priority (U.S. or foreign) under 35 U.S.C. §§ 119, 120, 121, 365, or 386, the named inventors must be the same—or at least one named joint inventor must be in common—and must be natural persons. Priority claims to foreign applications that name an AI tool as the sole inventor will not be accepted. Where a foreign application names both a natural person and a non-natural person (e.g., an AI) as joint inventors, the U.S. filing must list only the natural person(s), including at least one in common with the foreign filing. The same approach applies to national stage entries under 35 U.S.C. § 371: name the natural person(s) as inventor(s) in the application data sheet accompanying the initial U.S. submission.

Practical Implications and Action Items for Patent Strategy

Document human conception thoroughly. Maintain detailed inventor notebooks (electronic or paper) that describe, in the inventor’s own words, the definite and permanent idea of the complete and operative invention—especially the claim limitations—before or contemporaneous with AI use. Capture prompts, inputs, iterations, and the human analysis that distills AI outputs into specific claim language or design features. This helps establish the inventor’s possession and particularity.

Treat AI outputs like lab results, where feasible. If AI “conceives” part of the “invention” to be claimed, conduct careful analysis of whether there is sufficient human conception. Position AI as an instrument that provides data or suggestions. The decisive step is the human’s mental formation of the complete and operative invention—a specific solution and claimable features—not the mere receipt of AI-generated content.

Adjust cross-border filing strategies. In jurisdictions that allow non-human inventors, plan ahead to avoid misalignment with U.S. requirements. Ensure that priority chains retain at least one natural-person inventor in common and that U.S. filings exclude non-natural persons from inventorship. Coordinate with foreign counsel on naming conventions to preserve U.S. priority.

Prepare for examiner scrutiny. Anticipate that examiners may question inventorship in filings that discuss AI extensively. Have ready documentation demonstrating human conception and the particular claim limitations conceived by the human inventor(s), as well as appropriate inventorship declarations.

What Did Not Change

Despite evolving capabilities, AI cannot be named as an inventor in the U.S., and the inventorship standard is unchanged: it centers on human conception.

Traditional inventorship doctrines continue to apply. Conception, joint inventorship, and priority requirements remain grounded in statutory and Federal Circuit principles. AI is treated as a tool, not as a co-inventor.

Claims drive the analysis. Whether one inventor or many, the question is who (or what) conceived the limitations of the claimed invention. The presence of AI does not alter the claim-centric nature of inventorship assessments.

Bottom Line

The USPTO’s New Guidance simplifies and clarifies the path forward: there is no AI-specific inventorship test, AI cannot be named as an inventor, and traditional conception standards govern. For single-inventor, AI-assisted cases, focus on documenting human conception with particularity. For multi-inventor scenarios, continue to apply Pannu among human contributors. Extend these principles across utility, design, and plant filings, and ensure priority claims align with natural person inventorship to avoid fatal defects. With careful documentation and claim-focused analysis, AI can be a powerful instrument in innovation while maintaining clear, defensible human inventorship.

New Inventorship Guidance on AI-Assisted Inventions- AI Can’t Be an Inventor, But AI Can Be a Tool in the Inventive Process (For Now…)

As readers may recall, in February 2024, the USPTO issued guidance on inventorship in AI-assisted inventions, which we wrote about here. On November 26, 2025, the USPTO rescinded that guidance and replaced it with new guidance.

By way of background, the February 2024 Guidance analyzed the naming of inventors for AI-assisted inventions using the Pannu factors, which state that an inventor must (1) contribute in some significant manner to the conception or reduction to practice of an invention, (2) make a contribution to the claimed invention that is not insignificant in quality when measured against the full invention, and (3) do more than merely explain well-known concepts and/or the current state of the art. In the February 2024 Guidance, the USPTO noted that in the context of AI-assisted inventions, the Pannu factors were informed by the following considerations:

Use of an AI system in creating an AI-assisted invention does not categorically negate the natural person’s contributions as an inventor, if the natural person “contributes significantly” to the invention

Providing a recognized problem or a general goal or research plan to an AI system does not rise to the level of conception

Reduction of the output of an AI system to practice alone is not a significant contribution that rises to the level of inventorship

A natural person who designs, builds, or trains an AI system in view of a specific problem to generate a particular solution could be an inventor

Owning or overseeing an AI system used in the creation of an invention does not constitute a significant contribution to conception

The November 2025 Guidance withdraws the analysis of the Pannu factors, indicating that the Pannu factors only apply when determining when multiple natural persons qualify as inventors. The November 2025 Guidance further emphasizes that the same legal standard for determining inventorship applies, whether or not AI systems were used in the inventive process. AI systems are described as tools, analogous to laboratory equipment, computer software, research databases, and the like. And under well-established practice, inventors can use the services of others – including AI systems – without those sources becoming co-inventors.

This Guidance significantly simplifies the analysis of how AI systems can be used in the inventive process. In removing the Pannu factors from the analysis of whether an AI system is an inventor, the November 2025 Guidance allows inventors to extensively use AI systems in developing an invention without needing to consider the extent to which an inventor used an AI system – such as tracking the prompts used by an inventor to prompt an AI system to generate an invention, characterizing the nature of the prompts as describing a general problem, directing an AI system towards a particular solution, or the like.

This change may also reduce the likelihood of AI creators being deemed co-inventors, because they are only considered as tool-builders. For example, in an AI-assisted drug discovery collaboration between AI experts and drug discovery scientists, under the new Guidance, the drug discovery scientists may use the services, ideas, and aid of the AI system without any concern that the AI system or its creators could become co-inventors. However, whether the AI experts are inventors should be assessed.

In short, the November 2025 Guidance reiterates that AI systems themselves cannot be named as an inventor on a patent application or issued patent. This is in line with the Federal Circuit’s decision in Thaler v. Vidal, 43 F.4th 1207 (Fed. Cir. 2022), in which the Federal Circuit held that only natural persons could be listed as inventors on a patent application or issued patent. Thus, past policy involving the rejection of claims under 35 U.S.C. § 101 and 115 for claims in any application in which an AI system is listed as an inventor or joint inventor remains in place. Relatedly, because only natural persons can be listed as inventors on a patent application or an issued patent, priority claims to foreign applications that name an AI tool as a sole inventor will not be accepted, and the ADS for US patent applications should only name natural persons even when claiming priority to a foreign application including natural persons and AI tools as joint inventors.

We would observe that this is an administrative change, subject to recission by subsequent notice and comment. Because this may not be a permanent change, it may still be worth preserving evidence of how inventors use AI systems in the inventive process to defend against future challenges to patent validity.

UKIPO Set to Increase Fees for the First Time in Years from April 2026

On 5 November 2025, the UK Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO) announced that, subject to legislative approval, fees for patents, trade marks and designs will rise from 1 April 2026. This marks the first major adjustment in years: trade mark fees have not increased since 1998, design fees since 2016 and patent fees since 2018.

Summary of Changes

Fees will increase by an average of 25% across all intellectual property rights. Some key changes are summarised below:

The trade mark application fee will increase from £170 to £205, with the fee for each additional class increasing from £50 to £60;

The trade mark renewal fee will increase from £200 to 245, with the fee for each additional class increasing from £50 to £60; and

The fees for single and multiple design applications will increase slightly, whilst design renewals will see a relatively larger increase in fees. In addition, the fee to register a deferred design will increase from £40 to £50 per design.

The UKIPO cites rising operational costs and inflation as the driving forces behind the changes. For the UKIPO’s full list of current and new fees, see here.

Timing and Transition

The new fees will take effect on 1 April 2026. Until then, current rates remain in place. The UKIPO will issue detailed guidance early next year to help businesses whose fees are due around that time navigate the transition.

Takeaways

These changes underscore the importance of proactive IP management. If you have filings or renewals on the horizon, consider accelerating them to benefit from current rates. If you wish to discuss how the new UKIPO fee structure could impact your portfolio, please contact us and we would be happy to advise on your specific circumstances.

Sophie Verstraeten contributed to this article

Getty Images (US) Inc (and others) v Stability AI Limited. Input- Getty Images v Stability AI. Output: Continued Uncertainty.

On 4 November 2025 the UK High Court handed down its judgment in the case of Getty Images (US) Inc (and others) v Stability AI Limited [2025] EWHC 2863 (Ch) [High Court Judgment Template].

The case concerned the training, development and deployment of Stability AI’s “Stable Diffusion” generative AI model and, as one of the first and to date most high-profile intellectual property (IP) infringement claims against an AI developer to make it all the way to trial in the UK courts, was originally envisaged as having potential to provide much-needed wide-ranging judicial guidance on the application of existing UK IP law in the field of AI. However, as the case progressed and the scope of Getty’s claims gradually reduced to a shadow of the original, it became apparent that this judgment, whilst still of note in respect of a number of key issues, would not be the silver bullet which many had originally anticipated.

At over 200 pages the judgment is long and complex, including detailed discussion of the witness and expert evidence which the Court considered before reaching its findings.

Key takeaways at a high-level are:

Primary Copyright Infringement: by close of evidence at the trial Getty had abandoned its key claims alleging that the training of Stability AI’s “Stable Diffusion” AI model and certain of its outputs had infringed Getty UK copyright works and/or database rights. Key reasons for this decision on the part of Getty would appear to be relatively limited evidence of actual potentially infringing output coupled with an acknowledgement that the development and training of Stable Diffusion had not taken place in the UK despite Getty’s claim being in respect of its UK rights. As a result, the Court declined to rule on these claims – meaning that the current legal uncertainty in this area continues, to the frustration of many.

Secondary Copyright Infringement: for the purposes of establishing a secondary copyright infringement claim, the Court has confirmed that the model weights used in the training of an AI model can be considered “articles” for the purposes of the relevant legislation. However, in this case the Court went on to find that those model weights did not themselves contain any Getty copyright works and so could not be considered an infringing copy. Whilst this is helpful guidance, it has long been accepted that references to an “article” in the relevant legislation covers both tangible and intangible items, hence this was an unsurprising decision for the Court to reach.

Trade Mark Infringement: the Court held that there was some limited evidence that certain earlier versions of Stable Diffusion had produced outputs which included a “Getty Images” UK registered trade mark as a watermark thereby infringing Getty’s registered trade mark. However, the Court emphasised that this finding is both “historic and extremely limited in scope” and that as a result of changes which had been made to later versions of Stable Diffusion, it could not hold that there was likely to be any continuing proliferation of such infringing output from Stable Diffusion.

Exclusive Licensee Claims: the Court has confirmed that when bringing a copyright infringement claim in the capacity of an exclusive licensee (as opposed to copyright owner) the Court will consider in detail whether the licences in question meet the relevant legislative definition of an “exclusive licence”. As such, it must be a completely exclusive licence, excluding even the rights of the copyright owner themselves, granted to only one licensee and it must be signed. That said, the Court will be willing to apply a very broad definition when deciding whether those have been “signed” (e.g. not just wet ink but includes online acceptance). Again, whilst useful guidance, this essentially just confirms the already accepted interpretation of this legislation.

Additional Damages Claim: as a result of the very limited findings of trade mark infringement on the part of Stability AI alongside the abandonment of the primary copyright infringement claims and failure of the secondary copyright infringement claim, the Court rejected Getty’s claims for additional/aggravated damages. The Judge noted that she could not hold that there had been any blatant and widespread infringement of UK IP rights by Stability AI, as Getty had claimed which would have justified an award of such damages.

For a more detailed summary and analysis of the case and each of these issues please see our full client briefing.

Car Shipper’s Federal — But Not State — Trade Secrets Claims Survive in Alleged Cross-Border Undercutting Scheme

Montway LLC is an Illinois-based leading automotive-transport broker that assists customers with transporting their vehicles across the country to alleviate them of the burden of driving those vehicles themselves.

In Montway’s industry, a customer who wants to ship her car reaches out to a broker with her location, destination, and vehicle information. The broker — like Montway — responds with a quote and posts the shipping job to a centralized “load board” viewable by other brokers and carriers, or the entities who would physically transport a vehicle. If a carrier thinks that the offered price is fair, then it may accept the job. The broker then connects the carrier and the customer and takes a cut of the quoted price as a broker’s fee. To maintain the competitiveness of the brokerage system and to prevent undercutting, brokers do not include a customer’s identity or contact information.

Montway operates a Bulgaria-based subsidiary, MDG EOOD, that runs its sales operation. MDG EOOD had two employees: Ivan Karakostov and Radion Tzakov. In 2023, while still employed by MDG EOOD, Karakostov formed a competing broker, Navi Transport Services LLC. Soon after he formed the company and quit MDG EOOD, Karakostov approached Tzakov and encouraged him to leave MDG EOOD and join Navi, which he did.

After Karakostov and Tzakov left, Montway observed a consistent pattern. For multiple customer inquiries that Montway had internally recorded and quoted — but before those customers accepted Montway’s quotes and before any job was posted to the load board — Navi appeared on the load board posting with what Montway describes as the same shipment at a lower price. Montway then lost the opportunity. Montway alleged that the most plausible explanation was that Navi was obtaining the identities and contact details of Montway’s prospective customers from current Montway employees and then using that information to send unsolicited, lower quotes that undercut Montway.

There were other factors that made Montway suspicious. Navi’s website generally resembled Montway’s, including its terms of use page. It also contained a handful of peculiar, similarly worded reviews, including multiple reviews by people with the same name. One customer even stated in a review that Navi “solicited” her business. And Navi’s website claimed that it had shipped more than 20,000 vehicles despite being new and having a minimal online footprint.Montway and MDG EOOD sued Navi, Karakostov, and Tzakov for inter alia, misappropriation under the federal Defend Trade Secrets Act (DTSA) and the Delaware Uniform Trade Secrets Act (DUTSA).

Case Information

Montway LLC v. Navi Transport Services LLC, No. 25-cv-00381, 2025 WL 3151403 (D. Del. Nov. 11, 2025)

Plaintiffs: Montway LLC and MDG EOODDefendants: Navi Transport Services, LLC, Ivan Karakostov, Radion TzakovJudge: Stephanos Bibas, sitting by designation.

Analysis and Outcome

The court denied Navi’s, Karakostov’s, and Tzakov’s motion to dismiss with respect to Montway’s DTSA claim in part.

The court held that Montway plausibly alleged protectable trade secrets in the identities and contact information of its potential customers, but not in its price quotes. This is because Montway reasonably maintained the secrecy of its customer identities and contact information by training employees on confidentiality, maintaining internal confidentiality policies and procedures, and imposing electronic safeguards to limit access. By contrast, Montway’s quotes were not kept secret. Once accepted, the quotes were functionally public via the load board, even if customer identities were withheld. And Montway’s customer information gained value from its secrecy because, otherwise, competitors could use the information to submit cheaper quotes and undercut the broker, destroying the broker’s first‑mover advantage.

As to misappropriation, the complaint adequately alleged that Navi used Montway’s trade secrets without consent and acquired them through improper means, namely by inducing or receiving confidential lead and contact information from current Montway employees who owed a duty of confidentiality. Although the allegations were circumstantial, the court emphasized that pleading misappropriation through circumstantial evidence is permissible where there are sufficient “plus factors” making misappropriation plausible rather than speculative. The complaint alleged several such factors.

Navi’s negligible web presence relative to Montway.

The timing pattern in which Navi posted ostensibly identical jobs at lower prices before Montway’s prospects accepted Montway’s quotes.

AA customer review indicating that Navi “solicited” business, consistent with unsolicited outreach rather than inbound inquiries.

Taken together, these facts plausibly supported the inference that Navi was using Montway’s confidential lead information to target and undercut Montway’s prospects.

Accordingly, the court denied dismissal of the DTSA claim against Navi, but only to the extent the asserted trade secrets are the identities and contact information of Montway’s potential customers. Additionally, the court denied the motion with respect to Montway’s DTSA claim against Karakostov and Tzakov personally because allegations reflect that they were personally responsible for obtaining Montway’s trade secrets and because they knew Navi’s leads were gained through improper means. The court dismissed any DTSA theory premised on Montway’s quotes themselves.

The court, however, dismissed Montway’s DUTSA claim against the defendants without prejudice because the complaint did not plausibly allege that misappropriation occurred “in” Delaware. Based on the pleaded facts, the relevant conduct occurred in Bulgaria or possibly Illinois, but not Delaware. The court permitted Montway to amend its complaint to add more facts to support the DUTSA claim

John M. Hindley and Nicole Curtis Martinez contributed to this article