The AI Royal Flush: The Five Foundations of Artificial Intelligence, Part 2

This is Part 2 of a summary of Ward and Smith Certified AI Governance Professional and IP attorney Angela Doughty’s comprehensive overview of the potential impacts of the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) for in-house counsel.

Generative AI Best Practices for In-House Counsel

Considering all of the risks and responsibilities outlined in Part 1 of this series, Doughty advises in-house counsel to mandate training, discuss with the management team control of approved tools, and organize a review of what data can be used with AI at each company level.

TRAINING

Training has the potential to bridge generational gaps and create a working environment where people are more comfortable sharing new ideas. “I am very proud of our firm for the way that we have adapted to the modern business landscape,” noted Doughty. “We have some folks who have been practicing for 30 to 40 years, and we have some right out of law school. With everyone evolving and learning at the same rate, we’re using training to build a more inclusive culture.”

HUMAN REVIEW

Having an actual human review key decisions is another best practice. In a case where an experienced person would not have required an additional layer of review, but AI is being used to streamline the process, prudent companies should conduct a secondary review of the AI-generated work.

MONITOR REGULATIONS

Similar to the technology, the regulatory environment is constantly in flux. Most of the potential regulations are currently just proposals that are not legally binding. For example:

The EU AI Act is a comprehensive legislative framework that aims to regulate AI technologies based on their level of risk. It’s designed to ensure that AI systems used in the EU are safe and respect fundamental rights and EU values.

The U.S. Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights outlines principles to protect the public from the potential harms of AI and automated systems, focusing on civil rights and democratic values in the U.S.

The FTC enforces consumer protection laws relevant to AI, focusing on issues like fairness, transparency, bias, and data privacy, but it currently operates within a more reactive and general deceptive trade practices legal framework.

Like the future, the final rules are impossible to predict. Doughty expects that transparency, fairness, and explainability will be common themes.

Regulators will want to know how decisions were made, whether AI was involved, how data is processed, and how data is protected. “They will not hesitate to hold senior-level people accountable. This is partially why clear policies are an effective strategy for minimizing risk,” commented Doughty.

Different regions have different ideas regarding ethics and bias. This increases the challenge of navigating the evolving regulatory framework.

COMPLIANCE

“Compliance with all of the standards is practically impossible, which makes this very similar to data protection and privacy. One of my worst nightmares is when a client asks me to make them compliant,” added Doughty, “because, in most cases, it’s simply not feasible.”

Penalties are likely to vary in proportion to the risk to society. Companies should consider whether using AI is worth the reputational damage and harm it could cause to individuals.

Businesses operating in high-risk sectors may see additional regulations compared to other businesses. It is a patchwork of inconsistent, overlapping laws, and that is unlikely to change. “If there is a positive to this, it is that it will keep us in business for a long time,” joked Doughty.

Legal knowledge will continue to be vital for helping clients make decisions. Critical thinking skills and an understanding of jurisprudence will also continue to support job security for attorneys.

Remember, AI is a Tool, not a Replacement.

“As attorneys, we have empathy skills. People don’t want to sit in front of a computer and talk about really difficult, hard things. They want to look you in the eyes,” Doughty explained.

AI is just a tool, and fears over being replaced may be overblown. Doughty is using the technology on a daily basis. Along with using it to edit her presentation into bullet points for experienced in-house attorneys, she uses it to draft legal scenarios.

Doughty advises not to use a person’s real name because of privacy. “I also use it when I am frustrated with someone, so I draft how I really feel, then ask the AI to make it more professional,” noted Doughty.

AI can quickly write an article if provided with a topic, a target audience, and a few links. The speed and accuracy are astonishing, but many believe it is difficult, if not impossible, to determine whether the copy was plagiarized. This is likely to be the subject of ongoing litigation.

Audience Questions Answered

In the Q&A portion of the presentation, the audience questions came in quickly. Doughty attempted to address all she could in the time allotted and offered to take calls regarding questions after the program.

In response to a question centered on navigating ongoing regulations, Doughty advised following the National Institute of Standards and Technology Cybersecurity Framework.

Another audience member wondered, “Can AI be trusted?”

“No, it cannot be trusted at all,” said Doughty. “There is not a single tool that I would recommend using as the basis for legal decisions without substantial human oversight – same as you would with any other technology tool.”

“What technology or change, if any, compares to the effect generative AI is having on the legal system and profession?”

“I don’t think we’ve seen anything like this since Word, Excel, and Outlook came out in terms of changing the way that we practice law and prepare legal work products. I remember having to go from the book stacks to Westlaw; it was just a different way to do research, but I still had to do all of those things. This is even more revolutionary than what we saw at that point.”

“How do you mitigate the risk of harmful bias in a vendor agreement?”

“The short answer is to fully vet your vendors. Many vendors understand the risks and will include representations and warranties within their contracts, but this one is difficult. Understanding the training model and data used for training can be key, as it was with the earlier examples of AI hiring tools trained in male-dominated industries that preferred male applicants.”

“Any tips to bring up the topic of AI to organizational leadership?”

“Quantify the risk and discuss all of the penalties that could occur, along with the opportunity costs associated with ruining a deal.”

“Are there any legal-specific AI tools that you see as a good value?”

“In terms of legal research, writing, or counsel, I would not advise using AI for any of that right now – outside of the (very) expensive, but known, traditional legal vendors, such as Westlaw and Thompson Reuters. This is partially because most of the AI tools people are using are open AI tools. This means every question and answer – right or wrong – is being used to train the technology. This is also partially because to ethically use these tools, we must understand their strengths and weaknesses enough to provide sufficient oversight, and many attorneys are not there yet.”

“What about IP infringement?”

“If AI has been predominantly trained on existing content and you use it to create an article, does the writer have an infringement claim? This is to be determined, and it’s one of the biggest issues being litigated right now. There are a slew of artists that are suing Gen AI companies for this purpose.”

“What about the environmental impact of AI processing?”

“Generative AI significantly impacts the environment due to its high energy consumption, especially during the training and operation of large models, leading to substantial carbon emissions. The use of resource-intensive hardware and the cooling needs of data centers further exacerbate this impact.”

“Any suggestions for when the IT department believes their understanding of the risks supersede the opinions of the legal department?”

“This is when the C-suite needs to come in because the legal risk and responsibility are already out there, and implementation is under a completely different department. It’s a business decision. I look at the IT department no different than the marketing or sales departments in determining the legal risk and making a recommendation.”

“Any recommendations for AI-based tools to stay on top of the regulatory tsunami?”

“Not yet, but I spend a lot of time listening to demos and participating in vendor training sessions. Signing up for trade association newsletters is another way to stay current. These are free resources for training and help with staying current on industry trends and proposed regulations.”

Conclusion

Doughty concluded the session by reminding the group of In-House Counsel that their ethical duties and responsibilities extend to governance, compliance, risk management, and an ongoing understanding of the ever-evolving landscape of Generative AI.

Court: Training AI Model Based on Copyrighted Data Is Not Fair Use as a Matter of Law

In what may turn out to be an influential decision, Judge Stephanos Bibas ruled as a matter of law in Thompson Reuters v. Ross Intelligence that creating short summaries of law to train Ross Intelligence’s artificial intelligence legal research application not only infringes Thompson Reuters’ copyrights as a matter of law but that the copying is not fair use. Judge Bibas had previously ruled that infringement and fair use were issues for the jury but changed his mind: “A smart man knows when he is right; a wise man knows when he is wrong.”

At issue in the case was whether Ross Intelligence directly infringed Thompson Reuters’ copyrights in its case law headnotes that are organized by Westlaw’s proprietary Key Number system. Thompson Reuters contended that Ross Intelligence’s contractor copied those headnotes to create “Bulk Memos.” Ross Intelligence used the Bulk Memos to train its competitive AI-powered legal research tool. Judge Bibas ruled that (i) the West headnotes were sufficiently original and creative to be copyrightable, and (ii) some of the Bulk Memos used by Ross were so similar that they infringed as a matter of law.

The court rejected Ross Intelligence merger and scènes à faire arguments. Though the headnotes were drawn directly from uncopyrightable judicial opinions, the court analogized them to the choices made by a sculptor in selecting what to remove from a slab of marble. Thus, even though the words or phrases used in the headnotes might be found in the underlying opinions, Thompson Reuters’ selection of which words and phrases to use was entitled to copyright protection. Interestingly, the court stated that “even a headnote taken verbatim from an opinion is a carefully chosen fraction of the whole,” which “expresses the editor’s idea about what the important point of law from the opinion is.” According to the court, that is enough of a “creative spark” to be copyrightable. In other words, even if a work is selected entirely from the public domain, the simple act of selection is enough to give rise to copyright protection.

Relying on testimony from Thompson Reuters’ expert, the court compared “one by one” how similar 2,830 Bulk Memos were to the West headnotes at issue. The found that 2,243 of the 2,830 Bulk Memos were infringing as a matter of law. Whether Ross Intelligence’s contractor had access to the headnotes was an open question, the court reasoned that a Bulk Memo that “looks more like a headnote that it does the underlying judicial opinion is strong circumstantial evidence of copying.” Questions of infringement are, of course, normally left for the fact finder, but the court found a reasonable juror could not conclude that the Bulk Memos were not copied from the West headnotes.

The court then went on to rule as a matter of law that Ross Intelligence’s fair use defense failed – even though only two of the four fair use factors favored Thompson Reuters. The court specifically found that Ross Intelligence’s use was commercial in nature and non-transformative because the use did not have a “further purpose or character” apart from Thompson Reuters’ use. The court also found dispositive that Ross’ intended purpose was to compete with Thompson Reuters, and thus would impact the market for Thompson Reuters’ service. The court, on the other hand, found that the relative lack of creativity in the headnotes, and the fact that users of Ross’ systems would never see them, also favored Ross.

The court distinguished cases holding that intermediate copying of computer source code was fair use, reasoning that those courts held that the intermediate copying was necessary to “reverse engineer access to the unprotected functional elements within a program.” Here, copying Thompson Reuters’ protected expression was not needed to gain access to underlying ideas. How this reasoning will play out in other pending artificial intelligence cases where fair use will be hotly contested is anyone’s guess – in most of those cases, the defendants would argue that they are not competing with the rights owners and that, in fact, the underlying ideas (not the expression) are precisely what the copying is trying access.

The court left many issues for trial (including whether Ross infringed the West Key Number system and thousands of other headnotes). Nonetheless, the opinion seems to be striking victory for content owners in their fight against the AI onslaught. Although Judge Bibas has only been on the Third Circuit bench since 2017, he has gained a reputation for his thoughtful and scholarly approach to the law. Whether his ruling sitting by designation as a trial judge in the District of Delaware can make it past his colleagues on the Third Circuit will be worth watching.

The case is Thomson Reuters Enterprise Centre GmbH et al v. ROSS Intelligence Inc., Docket No. 1:20-cv-00613 (D. Del. May 06, 2020).

Navigating Text Messages in Discovery

In We The Protesters, Inc., et al., v. Sinyangwe et. Al, the Southern District of New York was recently called upon to resolve a discovery dispute that, according to the Magistrate Judge, “underscore[d] the importance of counsel fashioning clear and comprehensive agreements when navigating the perils and pitfalls of electronic discovery.” More specifically, the court was determining whether, without an express agreement between the parties’ counsel in place, plaintiffs could properly redact text messages based on responsiveness.

We The Protesters, Inc. Background

The litigation arose from a business divorce between the founders of nonprofit Campaign Zero. Plaintiffs’ complaint asserted 17 causes of action for inter alia, trademark infringement, unfair competition, misappropriation, and conversion. Defendants counterclaimed, accusing plaintiffs of copyright infringement, trademark infringement, cyberpiracy, and unfair competition.

In March 2024, the Hon. John P. Cronan granted in part and denied in part plaintiffs’ motion to dismiss three of defendants’ counterclaims. Discovery proceeded and the current dispute came to light after the parties exchanged productions of text messages and direct messages from a social media platform.

In drafting the operative discovery protocol, the parties agreed to collect and review all text messages in the same chain on the same day whenever a text within the chain hit on an agreed-upon search term. (Dkt. No. 64 at 1 & Ex. A). Plaintiffs understood this to mean they needed to produce only the portions of the messages from the same-day text chain that were responsive or provided context for a responsive text message.

Defendants had a different understanding, claiming the entire same-day text chain must be produced in unredacted form. Upon reviewing plaintiffs’ production, defendants objected and claimed plaintiffs’ unilateral redaction of these text messages was improper. Following an unsuccessful meet and confer, defendants filed a letter-motion seeking to compel production of unredacted copies of all text messages in the same chain that were sent or received within the same day. Plaintiffs responded, contending their redactions were proper and, in the alternative, seeking a protective order.

Discussion

Text Messages in Discovery

The court’s decision began with the observation that text messages are an increasingly common source of relevant and often critical evidence in 21st century litigation.[1] According to the court, text messages do not fit neatly into the paradigms for document discovery embodied by Rule 34 of the Federal Rules. Although amended in 2006 to acknowledge the existence of electronically stored information (ESI), i.e., email, the rules were crafted with different modes of communication in mind. Unlike emails, with text messages each text or chain cannot necessarily be viewed as a single, identifiable “document.”

And so, the issue is whether, for discovery purposes, each text message should be viewed as its own stand-alone “document”? Or is the relevant “document” the entire chain of text messages between the custodian and the other individual(s) on the chain, which could comprise hundreds or thousands of messages spanning innumerable topics?[2]

As the opinion notes, federal courts have adopted different approaches with respect to text messages. Some courts, including the Southern District of New York, suggest that a party must produce the entirety of a text message conversation that contains at least some responsive messages.[3] By contrast, other jurisdictions, like the Northern District of Ohio, hold “the producing party can unilaterally withhold portions of a text message chain that are not relevant to the case.”[4] “Still other courts have taken a middle ground.”[5]

Against this backdrop, the court noted that litigants are free to—and are well-advised to—mitigate the risk of this uncertain legal regime by agreeing on how to address text messages in discovery. Rule 29(b) specifically affords parties the flexibility to design their own, mutually agreed upon protocols for handling discovery, but “encourage[s]” counsel “to agree on less expensive and time-consuming methods to obtain information.”[6] Such “‘private ordering of civil discovery’” is “‘critical to maintaining an orderly federal system’” and “‘it is no exaggeration to say that the federal trial courts otherwise would be hopefully awash.’”[7]

The court noted a party may think twice about insisting on the most burdensome and costly method of reviewing and producing text messages for its adversary if it knows it will be subject to the same burden and cost. In general, the parties are better positioned than the court to customize a discovery protocol that suits the needs of the case given their greater familiarity with the facts, the likely significance of text message evidence, and the anticipated volume and costs of the discovery.[8]

Resolution Where Agreement is Incomplete

Here, the court noted the parties negotiated an agreement regarding the treatment of text messages. However, the agreement was incomplete. According to the court, email exchanged between the parties, along with the parties’ summary of the verbal discussions that took place show agreement that (1) discovery would include text messages; (2) specific search terms would be used to identify potentially responsive text messages; and (3) when a search term hit on a text message, counsel would review all messages in the same chain sent or received the same day, regardless of whether the text message that hit on the search term was responsive. The parties both produced responsive text messages in the form of same-day text chains, manifesting mutual assent that a same-day chain represented the appropriate unit of production. However, the parties’ agreement did not explicitly address whether, in producing those same-day text chains, texts deemed irrelevant and non-responsive would be redacted or, instead, the chains needed to be produced in their entirety. It was that failure that caused the instant dispute.

In resolving the dispute, the court viewed the issue through the prism of the parties’ prior agreement, discussions, and lack of discussions. The court indicated its task was not to determine the “right answer” to the redaction question in the abstract, but rather how to proceed with an agreement that was unknowingly incomplete. The court identified its task as akin to filling a gap in the parties’ incomplete agreement.[9]

In completing its task, the court noted the familiar principle of contract law that “contracting parties operate against the backdrop” of applicable law which, in this context, was supplied by Al Thani — the leading case in the Southern District on the issue of redactions from text messages and one authored by the presiding district judge in this litigation. Al Thani holds squarely that “parties may not unilaterally redact otherwise discoverable” information from text messages for reasons other than privilege.[10] Yet that is precisely what plaintiffs did.

The court further relied upon Judge Aaron’s decision in In re Actos Antitrust Litigation as instructive. In Actos, the issue involved “email threading,” i.e., the production of a final email chain in lieu of producing each separate constituent email. Specifically, a discovery dispute arose because defendants made productions “using email threading even though the Discovery Protocol, by its terms, did not permit such approach.”[11] Judge Aaron rejected defendants’ unilateral decision to use threading, explaining “if the issue had been raised when the parties were negotiating the Discovery Protocol, Plaintiffs may have been able to [avoid the issue], however, Plaintiffs were not provided the opportunity to negotiate how email threading might be accomplished in an acceptable manner.”[12] The court declined to impose threading on plaintiffs.

Here, the court found the Actos reasoning persuasive. If plaintiffs wanted to redact their text messages, it was incumbent upon them to negotiate an agreement to that effect or, in the absence of agreement, resolve the issue with the court before defendants made their production. Accordingly, as in Actos, the court construed the absence of a provision in the parties’ agreement allowing redaction of text messages to preclude plaintiffs from unilaterally redacting.

Considerations for Text Message Discovery

We The Protesters, Inc., is an important reminder of a few things. First, text messages and other forms of mobile instant messages are a critical form of evidence in today’s litigation. Any discovery protocol should address preservation, production, and potential redactions to that ESI. Additionally, given the cost and burden attendant to ESI, parties should leverage Rule 29(b) and fashion their own, mutually agreeable protocols for handling discovery, with an eye toward proportionality and efficiency. Finally, cooperation and communication are key in litigation. When in doubt, consider picking up the phone to opposing counsel. Here, had plaintiff confirmed its intention to redact content prior to production, much effort and cost may have been avoided.

[1] Mobile phone users in the United States sent an estimated 2 trillion SMS and MMS messages in 2021, or roughly 5.5 billion messages per day, a 25-fold increase from 2005. SMS and MMS messages represent only a subset of the universe of mobile instant messaging, or MIM, which also includes other means of messaging via mobile phones. MIM, in turn, does not account for the vast volume of instant messages, or IM, sent on computer-mediated communication platforms. The use of IM and MIM “has become an integral part of work since COVID-19.” Katrina Paerata, The Use of Workplace Instant Messaging Since COVID-19, Telematics and Informatics Reports (May 2023).

[2] After all, an email chain is typically confined to a single subject, whereas a single text chain can read more like a stream of consciousness covering countless topics.

[3] Lubrizol Corp. v. IBM Corp., (citing cases); see also Al Thani v. Hanke (noting the general rule that parties may not unilaterally redact otherwise discoverable documents for reasons other than privilege,) id. at *2; see also Vinci Brands LLC v. Coach Servs., Inc. (following Al Thani).

[4] Lubrizol at *4 (citing cases from various jurisdictions that follow this approach).

[5] Id. (citing cases from such jurisdictions).

[6] Id. 1993 Adv. Comm. Note.

[7] Brown v. Hearst Corp. (quoting 6 Moore’s Federal Practice § 26.101(1)(a)).

[8] See generally Jessica Erickson, Bespoke Discovery, 71 Vand. L. Rev. 1873, 1906 (2018) (“Parties should have more information than judges about the specific nature of their disputes and thus should be in a better position to predict the types of restrictions that will be appropriate.”).

[9] See In re World Trade Center Disaster Site Litig. (“In limited circumstances, a court may supply a missing term in a contract.”); Adler v. Payward, Inc.(“[C]ourts should supply reasonable terms to fill gaps in incomplete contracts.”) (citation omitted).

[10] Al Thani at *2.

[11] Id. at 551.

[12] Id.

Hangzhou Internet Court: Generative AI Output Infringes Copyright

On February 10, 2025, the Hangzhou Internet Court announced that an unnamed defendant’s generative artificial intelligence’s (AI) generating of images constituted contributory infringement of information network dissemination rights, and ordered the defendant to immediately stop the infringement and compensate for economic losses and reasonable expenses of 30,000 RMB.

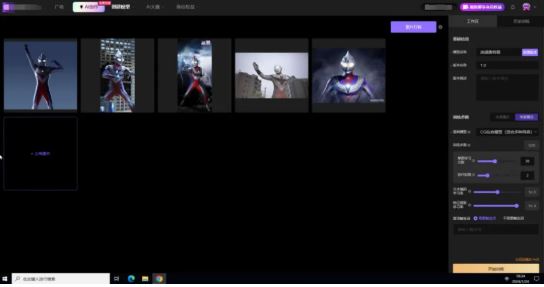

LoRA model training with Ultraman

Infringing image generated with the model.

The defendant operates an AI platform that provides Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) models, and supports many functions such as image generation and model online training. On the homepage of the platform and under “Recommendations” and “IP Works”, there are AI-generated pictures and LoRA models related to Ultraman, which can be applied, downloaded, published or shared. The Ultraman LoRA model was generated by users uploading Ultraman pictures, selecting the platform basic model, and adjusting parameters for training. Afterwards, other users could then input prompts, select the base model, and overlay the Ultraman LoRA model to generate images that closely resembled the Ultraman character.

The unnamed plaintiff (presumably Tsuburaya Productions) alleged that the defendant infringed on their information network dissemination rights by placing infringing images and models on the information network after training with input images. The defendant used generative AI technology to train the Ultraman LoRA model and generate infringing images, constituting unfair competition. The plaintiff demanded the defendant cease the infringement and compensate for economic damages of 300,000 RMB.

The defendant countered that their AI platform, by calling third-party open-source model code, integrates and deploys these models according to platform needs, offering a generative AI platform for users. However, the platform does not provide training data and only allows users to upload images to train the model, which falls within the “safe harbor” rule for platforms and does not constitute infringement.

The Court reasoned:

On the one hand, if the generative artificial intelligence platform directly implements actions protected by copyright, it may constitute direct infringement. However, in this case, there is no evidence to prove that the defendant and the user jointly provided infringing works, and the defendant did not directly implement actions protected by information network dissemination rights.

On the other hand, in this case, when the user inputs infringing images and other training materials and decides whether to generate and publish them, the defendant does not necessarily have an obligation to conduct prior review of the training images input by the user and the dissemination of the generated products. Only when it is at fault for the specific infringing behavior can it constitute aiding and abetting infringement.

Specifically, the following aspects are considered comprehensively:

First, the nature and profit model of generative AI services. The open source ecosystem is an important part of the AI industry, and the open source model provides a general basic algorithm. As a service provider directly facing end users at the application layer, the defendant has made targeted modifications and improvements based on the open source model in combination with specific application scenarios, and provided solutions and results that directly meet the use needs. Compared with the provider of the open source model, it directly participates in commercial practices and benefits from the content generated based on the targeted generation. From the perspective of service type, business logic and prevention cost, it should maintain sufficient understanding of the content in the specific application scenario and bear the corresponding duty of care. In addition, the defendant obtains income through users’ membership fees, and sets up incentives to encourage users to publish training models, etc. It can be considered that the defendant directly obtains economic benefits from the creative services provided by the platform.

Secondly, the popularity of the copyrighted work and the obviousness of the alleged infringement. Ultraman works are quite well-known. When browsing the platform homepage and specific categories, there are multiple infringing pictures, and the LoRA model cover or sample picture directly displays the infringing pictures, which is relatively obvious infringement.

Thirdly, the infringement consequences that generative AI may cause. Generally speaking, the results of user behavior using generative AI are not identifiable or intervenable, and the generated images are also random. However, in this case, because the Ultraman LoRA model is used, the characteristics of the character image can be stably output. At this time, the platform has enhanced the identifiability and intervention of the results of user behavior. And because of the convenience of technology, the pictures and LoRA models generated and published by users can be repeatedly used by other users. The trend of causing the spread of infringement consequences is already quite obvious, and the defendant should have foreseen the possibility of infringement.

Finally, whether reasonable measures have been taken to prevent infringement. The defendant stated in the platform user service agreement that it would not review the content uploaded and published by users. After receiving the lawsuit notice, it has taken measures such as blocking relevant content and conducting intellectual property review in the background, proving that it has the ability to take but has failed to take necessary measures to prevent infringement that are consistent with the technical level at the time of the infringement.

In summary, the defendant should have known that network users used its services to infringe upon the right of information network dissemination but did not take necessary prevention measures. It failed to fulfill his duty of reasonable care and was subjectively at fault, constituting aiding and abetting infringement.

Violations of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law did not need to be considered as copyright infringement was determined.

The full text of the announcement is available here (Chinese only).

With Enough Human Contribution, AI-Generated Outputs May Be Copyright Protectable

After several months of delays, the U.S. Copyright Office has published part two of its three-part report on the copyright issues raised by artificial intelligence (AI). This part, entitled “Copyrightability,” focuses on whether AI-generated content is eligible for copyright protection in the U.S.

An output generated with the assistance of AI is eligible for copyright protection if there is sufficient human contribution. The report notes that copyright law does not need to be updated to support this conclusion. The Supreme Court has explained that individuals can receive copyright protection when they translate an idea into a fixed and tangible medium. When an AI model supplies all creative effort, no human can be considered an author, thus no copyrightable work. However, when an AI model assists a human’s creative expression, the human is considered an author. The Copyright Office analogizes this to the principle of joint authorship because a work is copyright-eligible even if a single person is not responsible for creating the entire work.

The contribution level is determined by what a person provides to the AI model. The Copyright Office reasoned that inputting a prompt by itself is not a sufficient contribution to be considered an author. The report analogizes this to a person hiring an artist, where the person may have a general artistic vision, but the artist produces the creative work. Additionally, because AI models generally operate as a black box, a user is cannot exert the necessary level of control to be considered an author.

However, when a user inputs a prompt in combination with their original work, the resulting AI-generated output is copyrightable for the material that is perceivable from their expression. The author’s own work helps provide the AI model with a starting point and limits the range of outputs.

Finally, AI-generated content can be copyrightable when arranged or modified with human creativity. For example, while an AI-generated image is not copyrightable, a compilation of the images and a human-authored story can be protected by copyright. The Copyright Office is currently working on the third part of its report, which should be published later this year and will focus on the implications of using protected works to train AI models.

DeepSeek AI’s Security Woes + Impersonations: What You Need to Know

Soon after the Chinese generative artificial intelligence (AI) company DeepSeek emerged to compete with ChatGPT and Gemini, it was forced offline when “large-scale malicious attacks” targeted its servers. Speculation points to a distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attack.

Security researchers reported that DeepSeek “left one of its databases exposed on the internet, which could have allowed malicious actors to gain access to sensitive data… [t]he exposure also includes more than a million lines of log streams containing chat history, secret keys, backend details, and other highly sensitive information, such as API Secrets and operational metadata.”

On top of that, security researchers identified two malicious packages using the DeepSeek name posted to the Python Package Index (PyPI) starting on January 29, 2025. The packages are named deepseeek and deepseekai, which are “ostensibly client libraries for access to and interacting with the DeepSeek AI API, but they contained functions designed to collect user and computer data, as well as environment variables, which may contain API keys for cloud storage services, database credentials, etc.” Although PyPI quarantined the packages, developers worldwide downloaded them without knowing they were malicious. Researchers are warning developers to be careful with newly released packages “that pose as wrappers for popular services.”

Additionally, due to DeepSeek’s popularity, it is warning X users of fake social media accounts impersonating the company.

But wait, there’s more! Cybersecurity firms are looking closely at DeepSeek and are finding security flaws. One firm, Kela, was able to “jailbreak the model across a wide range of scenarios, enabling it to generate malicious outputs, such as ransomware development, fabrication of sensitive content, and detailed instructions for creating toxins and explosive devices.” DeepSeek’s chatbot provided completely made-up information to a query in one instance. The firm stated, “This response underscores that some outputs generated by DeepSeek are not trustworthy, highlighting the model’s lack of reliability and accuracy. Users cannot depend on DeepSeek for accurate or credible information in such cases.”

We remind our readers that TikTok and DeepSeek are based in China, and the same national security concerns apply to both companies. DeepSeek is unavailable in Italy due to information requests from the Italian DPA, Garante. The Irish Data Protection Commissioner is also requesting information from DeepSeek. In addition, there are reports that U.S.-based AI companies are investigating whether DeepSeek used OpenAI’s API to train its models without permission. Beware of DeepSeek’s risks and limitations, and consider refraining from using it at the present time. “As generative AI platforms from foreign adversaries enter the market, users should question the origin of the data used to train these technologies. They should also question the ownership of this data and ensure it was used ethically to generate responses,” said Jennifer Mahoney, Advisory Practice Manager, Data Governance, Privacy and Protection at Optiv. “Since privacy laws vary across countries, it’s important to be mindful of who’s accessing the information you input into these platforms and what’s being done with it.”

Dog Toy Maker in the Doghouse (Again) for Tarnishing Jack Daniel’s Marks

Addressing this case for the third time, the US District Court for the District of Arizona found on remand that Jack Daniel’s was entitled to a permanent injunction after finding that VIP Products’ “Bad Spaniels” dog toy diluted Jack Daniel’s trademark and trade dress, despite VIP not having infringed those marks. VIP Products LLC v. Jack Daniel’s Properties Inc., Case No. CV-14-02057-PHX-SMM (D. Ariz. Jan. 21, 2025).

This case began more than 10 years ago when VIP filed a declaratory judgment action that its “Bad Spaniels” Silly Squeaker dog toy did not infringe or dilute Jack Daniel’s trademark rights. Jack Daniel’s counterclaimed, alleging trademark infringement and dilution. The district court initially entered a permanent injunction against VIP, finding that VIP’s “Bad Spaniels” toy violated and tarnished Jack Daniel’s trademarks and trade dress. VIP appealed, and the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit found that VIP’s use of “Bad Spaniels” was protected expressive speech under the First Amendment. On remand, the district court granted summary judgment to VIP on infringement and dilution. Jack Daniel’s appealed, but the Ninth Circuit affirmed the grant of summary judgment.

The Supreme Court granted certiorari and held that the heightened protection afforded by the First Amendment does not apply where the contested mark is used as a trademark. The Supreme Court therefore vacated the Ninth Circuit’s decision and remanded for further consideration. The Ninth Circuit remanded the case to the district court to determine whether VIP’s use of “Bad Spaniels” tarnished and/or infringed Jack Daniel’s trademarks and trade dress, consistent with the Supreme Court’s decision.

On remand, VIP attempted to challenge the constitutionality of the Lanham Act’s cause of action for dilution by tarnishment, arguing that “the statute amounts to unconstitutional viewpoint discrimination by enjoining the use of a mark that ‘harms the reputation’ of a famous mark.” Ultimately, the district court did not consider the merits of the constitutional challenge. The district court stated that although it was not precluded from considering VIP’s constitutional challenge, the issue was not properly before the court because VIP had not amended its pleadings to assert the challenge.

The district court assessed dilution by tarnishment using a three-factor analysis of fame, similarity, and reputational harm. With respect to fame, the parties did not dispute that the JACK DANIEL’S mark was famous. Nonetheless, VIP contended that Jack Daniel’s had not shown tarnishment of a famous mark by a “correlative junior mark.” Specifically, VIP argued that the famous JACK DANIEL’S mark correlated with VIP’s “Bad Spaniels,” and VIP’s use of “Old. No. 2” correlated with Jack Daniel’s mark “Old No. 7.” According to VIP, there could be no tarnishment because only the latter was offensive and Jack Daniel’s had not demonstrated that “Old. No. 7” was a famous mark. The district court disagreed with VIP’s correlative mark argument, stating, “it is VIP’s use of Jack Daniel’s marks – on a poop-themed dog chew toy – that Jack Daniel’s claims tarnish its trademarks, not ‘Bad Spaniels’ itself when taken in isolation.”

The district court had already found a high degree of similarity between the marks, which VIP did not contest because the “Bad Spaniels” toy had been “intentionally designed” to mimic Jack Daniel’s Tennessee Whiskey.

Addressing the third factor (reputational harm), the district court stated that “the relevant inquiry is how the use of the junior mark affects the consumer’s positive impressions of the famous mark.” Here, because “Jack Daniel’s produces a product intended for human consumption, association of Jack Daniel’s marks with something like dog feces is particularly detrimental,” even if “it is obviously true that ‘Bad Spaniels’ does not actually contain dog feces and consumers would not believe that it does.”

Although VIP’s “parodic intentions in creating ‘Bad Spaniels’ d[id] not exempt VIP from the [Trademark Dilution Revision Act’s] cause of action for dilution by tarnishment,” the district court noted that the parody was relevant to the likelihood of confusion analysis. When assessing a parody’s impact on the infringement analysis, the court first reviewed whether VIP’s “Bad Spaniels” product evoked Jack Daniel’s, and “whether it creates contrasts through humor adequate to dispel confusion as to the source of the parody.” Here, the court found that “Bad Spaniels” met both factors because it “both evokes and humorously contrasts with Jack Daniel’s marks such that it succeeds as a parody.”

Having established that “Bad Spaniels” qualified as a successful parody, the district court turned to the typical likelihood of confusion factors. The court noted that the finding of parody tipped some factors that would ordinarily favor the plaintiff in VIP’s favor: “Adjusting the Sleekcraft [likelihood of confusion] factors to account for parody neutralizes or flips three important factors – similarity of the marks, VIP’s intent, and strength of Jack Daniel’s mark.”

Here, the similarity of the marks favored VIP, as similarities were necessary for the parody to successfully evoke the Jack Daniel’s marks. Likewise, the strength of Jack Daniel’s marks weighed in VIP’s favor, as the “widespread recognition of the parodied trademark” allowed the parody to avoid consumer confusion. Finally, VIP’s intent in selecting the mark was a neutral factor, as VIP did not intend to create confusion or deceive consumers, but to create a parody product.

Although VIP prevailed on the issue of trademark infringement, the district court nonetheless found that a permanent injunction was appropriate here because “‘Bad Spaniels’ finds itself in the category of a non-confusion parody product that is nonetheless impermissible under the Lanham Act’s cause of action for tarnishment.”

Practice Note: It will be interesting to see whether and how this case continues. The ruling leaves open the possibility for a constitutional challenge to the Lanham Act’s cause of action for dilution by tarnishment. For now, it suggests that parodies that may be sheltered from infringement are still susceptible to dilution by tarnishment.

Eye-Catching: Biosimilars Injunction Prevails

Addressing a preliminary injunction in patent litigation related to the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA), the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit upheld the district court’s grant of a preliminary injunction, finding that there was a proper exercise of personal jurisdiction and that no substantial question of invalidity had been raised for the patents at issue that would prevent the injunction from issuing. Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc., Case No. 24-1965 (Fed. Cir. Jan. 29, 2025) (Moore, C.J.; Reyna, Taranto, JJ.)

Regeneron holds a Biologics License Application for Eylea®, a therapeutic product containing aflibercept (a VEGF antagonist used in various treatments for eye diseases). Regeneron owns multiple patents related to its Eylea® product, including a patent directed to intravitreal injections using VEGF formulations. Mylan, Samsung Bioepis (SB), and other companies filed abbreviated Biologics License Applications (aBLAs) with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) seeking approval to market Eylea® biosimilars. Regeneron brought suit against these parties asserting infringement of its patent and filed a motion for a preliminary injunction.

The district court granted the preliminary injunction against SB, enjoining it from offering for sale or selling the subject of its aBLA without a license from Regeneron. SB appealed, arguing that:

The exercise of personal jurisdiction over it was improper.

There was a substantial question of invalidity of the patent under either obviousness-type double patenting or lack of adequate written description.

There was no causal nexus established.

The Federal Circuit upheld the exercise of personal jurisdiction on SB, finding that SB had minimum contacts with the state of West Virginia. SB is headquartered in South Korea and entered into a development and commercialization agreement with Biogen for a biosimilar to Eylea®, SB15, that gives SB continuing rights and responsibilities as the agreement is implemented. The Court found that SB did not have to distribute the product itself under the agreement for it to be subject to personal jurisdiction. Further, the Court found that SB’s aBLA and internal documentation indicated an intent to distribute SB15 US-wide, which was sufficient to establish intent to distribute the product in West Virginia.

The Federal Circuit also upheld the district court’s grant of the preliminary injunction. SB invoked another patent in the same family as the asserted patent that was directed to an intravitreal injection containing a VEGF trap as the reference patent for an obviousness-type double patenting theory. The Federal Circuit upheld the district court’s findings that the stability requirement, the “glycosylated” requirement, and the “vial” limitations in the claims of the asserted patent were all patentably distinct from the reference patent. The Court found that the stability requirement recited in the asserted patent was more specific than, and not inherent within, the reference patent. The Court further agreed that the reference patent embraced both non-glycosylated and glycosylated aflibercept, not only the glycosylated aflibercept contained in the asserted patent claims.

The Federal Circuit then addressed SB’s arguments that the specification lacked sufficient written description for the claimed glycosylation and stability requirements of the asserted patent. The Court rebuffed SB’s argument, finding that the specification described an embodiment with glycosylated aflibercept and crediting expert testimony that a person of ordinary skill in the art (POSA) would understand from the example that aflibercept could be glycosylated at those specific residues. The Court also disagreed with SB’s argument that the upper and lower bounds of the stability requirements were not described in the specification because a specification does not need to express the details of every embodiment of the invention, and credited expert testimony that a POSA would understand from the specification that those bounds would be included.

Finally, the Federal Circuit addressed SB’s argument that the district court erred in finding a causal nexus between SB’s infringement and Regeneron’s irreparable harm. The Court found no evidence that SB possessed or planned to commercialize a noninfringing product and found that the combination recited in the asserted claims (essentially the Eylea® product) was what drove consumer demand.

Rules Are Rules, Especially in Trademark Proceedings

The Commissioner for Trademarks recently issued a precedential decision terminating a reexamination proceeding for the registrant’s failure to respond within a statutory time period, where there was insufficient justification to waive the response requirement. In re Trigroup USA LLC, Reg. No. 7094794 (Jan. 24, 2025) (Gooder, Comm’r for Trademarks)

The Trademark Modernization Act of 2020 (TMA) created two new trademark proceedings: expungement and reexamination. The US Patent & Trademark Office (PTO) began accepting petitions for these proceedings in 2021. The reexamination proceeding must be filed within the first five years after the registration of a trademark and can only be filed against applications filed on the basis of use (§ 1(a)) or intent to use (§ 1(b)). The proceeding questions whether the mark was in use by a certain date:

In the case of a use-based application, the mark must have been in use on all the goods or services identified in the application by the filing date of the application.

In the case of an intent-to-use application, the mark must have been in use on all the goods or services identified in the application by either the date the Allegation of Use was filed or the deadline for filing the Statement of Use.

A party filing for reexamination must submit evidence that the mark was not in use by those relevant dates.

When the PTO institutes a reexamination proceeding, it issues an Office Action providing the registrant with the opportunity to rebut the claims of non-use. The rules require a response within three months of the Office Action issue date, and failure to respond results in the cancellation of the registration.

Here, the registrant did not respond to the Office Action, and the PTO cancelled the registration. The registrant then filed a Petition to the Director requesting reinstatement of the registration. Such a petition is required to include a response to the original Office Action. However, in this case, the registrant did not provide such a response, and on that basis the Commissioner found that the Petition should not be granted.

The Commissioner further found that even if the petition had included a complete response, it did not set forth sufficient facts to justify a late response. Trademark Rule 2.146(a)(5) permits the Director to waive any requirement of the rules that is not mandated by statute only “in an extraordinary situation, when justice requires, and no other party is injured.” 37 C.F.R. § 2.146(a)(5).

The registrant explained that it had an ongoing matter in China and the failure to respond was due to inadvertent error because it was dealing with the Chinese matter. The Commissioner found that this was not an extraordinary circumstance. The registrant also explained that cancellation of the registration would hinder its ongoing efforts in China and prevent it from manufacturing its products there. The Commissioner found that justice did not require the waiver of the PTO rules just because there would be harm to the registrant: “a party cannot be excused from the rule merely because the results in a particular case may be harsh.”

Practice Note: The Commissioner found that the registrant established neither an extraordinary circumstance nor that justice required a waiver of the rules to permit a late response and reinstate the registration. This is a lesson to practitioners to make sure that all responsive deadlines are met and to follow the rules and requirements because some mistakes are incurable.

Assessing Inputs: Determining AI’s Role in US Intellectual Property Protections

The US Patent & Trademark Office (PTO) issued additional guidance on the contribution of artificial intelligence (AI) in its January 2025 AI Strategy. Similarly, the US Copyright Office issued part two of its “Copyright and Artificial Intelligence” report, addressing the copyrightability of AI- or partially AI-made works. Both agencies appear to be walking a fine line by accepting that AI has become increasingly pervasive while maintaining human contribution requirements for protected works and inventions.

In its published strategy, the PTO states that its vision is to unleash “America’s potential through the adoption of AI.” The strategy describes five focus areas:

Advancing the development of intellectual property policies that promote inclusive AI innovation and creativity.

Building best-in-class AI capabilities by investing in computational infrastructure, data resources, and business-driven product development.

Promoting the responsible use of AI within the PTO and across the broader innovation ecosystem.

Developing AI expertise within the PTO’s workforce.

Collaborating with other US government agencies, international partners, and the public on shared AI priorities.

The PTO stated that it is still evaluating the issue of AI-assisted inventions but reaffirmed its February 2024 guidance on inventorship for AI-assisted inventions. That guidance indicates that while AI-assisted inventions are not categorically unpatentable, the inventorship analysis should focus on human contributions.

Likewise, the Copyright Office discussed public comments regarding AI contributions to copyright, weighing the benefits of AI in assisting and empowering creators with disabilities against the harm to artists working to make a living. Ultimately the Copyright Office affirmed that AI, when used as a tool, can generate copyrightable works only where a human is able to determine the expressive elements contained in the work. The Copyright Office stated that creativity in the AI prompt alone is, at this state, insufficient to satisfy the human expressive input required to produce a copyrightable work.

New PTAB Guidance on Enabling Requirement Under § 102 of the AIA and Construction of Chemical Compound

Synopsis: In a recently issued final written decision, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (the “Board”) found all challenged claims of U.S. Patent No.11,572,334 (“the ’334 patent”) unpatentable.1 The Board’s decision centered on two issues: (1) when does a prior art patent need to be enabled under § 102 of the America Invents Act (“AIA”) to qualify as an anticipatory reference and (2) as a matter of claim construction, is the claim phrase “the compound of Formula (III) is (Z)-endoxifen” limited to the free base form of endoxifen or does it also encompass other forms of endoxifen (i.e., salts, crystalline forms, solvates, etc.).

On the first point, the Board held that under the current AIA § 102, an anticipation reference must be enabling as of the earliest possible effective filing date of the challenged patent. That is a departure from the Federal Circuit’s precedent under pre-AIA § 102(b), which requires anticipation references to be enabling one year before the effective filing date of the challenged patent. The Board also clarified several procedural aspects related to enablement challenges of anticipation references, including that it is a Patent Owner’s initial burden to prove that an anticipation reference is not enabling, and the types of evidence that a Petitioner may rely on to rebut an enablement challenge.

Turning to claim construction, the Board initially construed the claim phrase “the compound of Formula (III) is (Z)-endoxifen” as encompassing various forms of (Z)-endoxifen in its institution decision. At trial, however, the Board requested additional briefing on the issue, and in its final written decision reversed course and construed the phrase as being limited to only the free base form of (Z)-endoxifen.

The Board’s holdings on these issues offer important guidance to both patent practitioners generally and Hatch-Waxman attorneys specifically.

I. Background

Atossa Therapeutics, Inc. (“Atossa” or “Patent Owner”) owns the ’334 patent, which is titled “Methods for Making and Using Endoxifen.” ’334 patent at Title. The ’334 patent explains that endoxifen is an active metabolite of a drug known as tamoxifen. Id., 2:36-38. “Tamoxifen is a selective estrogen receptor modulator that is used for the treatment of women with endocrine responsive breast cancer.” Id., 1:63-66.

The ’334 patent also explains that there are two isomers of endoxifen: (Z)-endoxifen and (E)-endoxifen. Id., 3:1-44. Of these two isomers, “[i]t is widely accepted that (Z)-endoxifen is the main active metabolite responsible for the clinical efficacy of tamoxifen.” Id., 2:36-38.

With those two points in mind, the ’334 patent discloses “industrially scalable methods of making (Z)-endoxifen or a salt thereof, crystalline forms of endoxif[e]n, and compositions comprising them” as well as “methods for treating hormone-dependent breast and hormone-dependent reproductive tract disorders.” Id., Abstract. The ’334 patent issued with 22 claims, including the following independent claims:

An oral formulation comprising an endoxifen composition encapsulated in an enteric capsule, wherein the endoxifen composition comprises a compound of Formula (III):

wherein at least 90% by weight of the compound of Formula (III) is (Z)-endoxifen.

A method of delivering (Z)-endoxifen to a subject, the method comprising administering to the subject an oral formulation comprising an endoxifen composition encapsulated in an enteric capsule, wherein the endoxifen composition comprises a compound of Formula (III):

wherein at least 90% by weight of the compound of Formula (III) is (Z)-endoxifen.

Id., claims 1 and 15.

Intas Pharmaceuticals Ltd. (“Intas” or “Petitioner”) markets endoxifen under the brand name Zonalta® in India where it is approved “[f]or the acute treatment of manic episodes with or without mixed features of Bipolar I disorder.”2 After the ’334 patent issued on February 7, 2023, Intas filed a petition requesting post-grant review (“PGR”) of all issued claims of the ’334 patent based on one anticipation ground and five separate obviousness grounds. PGR2023-00043, Paper 37 at 6. All six grounds relied on U.S. Patent No. 9,333,190 (“Ahmad”) as a prior art reference. Id.

II. The Board’s Final Written Decision

Anticipation references under AIA § 102 must be enabled as of the effective filing date of the challenged patent

The Board began its decision by noting, among other things, that because the ’334 patent’s earliest possible effective filing date is September 11, 2017, it is subject to the provisions of the AIA. Id. at 7. Likewise, the provisions of AIA § 102 were applied to Petitioner’s anticipation and obviousness grounds. Id., 15-20. That became highly relevant to the Board’s decision because although it has long been a requirement that “[a]n anticipatory reference must also be enabling,” there was “no controlling case law specifically addressing the timeframe of enablement of an anticipatory reference under the current AIA § 102.” Id., 15, 18-19.

The Board explained that “under pre-AIA § 102(b), the Federal Circuit held that the relevant timeframe for determining whether prior art reference is enabling is one year before the effective filing date of the patent-in-suit.” Id., 18 (citing Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. v. Ben Venue Lab’ys, Inc., 246 F.3d 1368, 1379 (Fed. Cir. 2001); In re Samour, 571 F.2d 559, 562–63 (CCPA 1978)). In other words, under pre-AIA § 102(b), a prior art reference must be enabling to a person of ordinary skill in the art (“POSA”) at least one year before the priority date of the challenged patent. That requirement was borne out of the one-year bar date of pre-AIA § 102(b). Id., 19.

Turning to the requirements of AIA § 102, the Board held that “[a]lthough AIA § 102(b)(1) provides for a one-year grace period under certain circumstances, that exception does not apply to the facts of this case.” Id. As a result, the Board agreed with Petitioner and “determine[d] that Ahmad need only be enabling prior to the earliest possible effective filing date of the ’334 Patent, i.e., on September 11, 2017.” Id.

Finally, Patent Owner argued that “[p]ost-effective filing date evidence offered to illuminate the post-effective filing date state of the art,” and to establish that an anticipatory reference is enabled, “is improper.” Id. (quoting Patent Owner Sur-reply at 12). The Board disagreed and clarified that under Bristol-Myers Squibb, “the Federal Circuit expressly held that ‘[e]nablement of an anticipatory reference may be demonstrated by a later reference.’” Id. (quoting 246 F.3d at 1379 (citing Donohue, 766 F.2d at 532; Samour, 571 F.2d at 562)). And the Board made clear that it is “Patent Owner’s burden to establish by a preponderance of the evidence that [an anticipatory reference] is not enabling,” consistent with the Federal Circuit’s prior holdings on that issue. Id., 17.

Application of the Board’s AIA § 102 enablement holding to Petitioner’s anticipation ground

Applying its new rule to Petitioner’s grounds, the Board found the claims anticipated. Notably, Patent Owner did not contest the fact that the prior art reference (Ahmad) disclosed every limitation of the challenged claims of the ’334 patent. Id., 20. Rather, Patent Owner argued that Ahmad did not enable the claimed invention as required by AIA § 102. Id. “Specifically, Patent Owner assert[ed] that Ahmad [did] not teach a POSA how to achieve 90% pure (Z)-endoxifen, as required by each of the claims.” Id. “Petitioner argue[d] that Ahmad [was] enabling because using 90% pure (Z)-endoxifen was in the public’s possession, as shown” by other references. Id., 20-21. The Board agreed with Petitioner and held that because Ahmad sufficiently enabled the claims, Patent Owner failed to carry its burden to prove that Ahmad was not enabling. Id., 21, 31.

The Board distinguished this case from two Federal Circuit cases relied on by Patent Owner: Forest Lab’ys, Inc. v. Ivax Pharms., Inc., 501 F.3d 1263 (Fed. Cir. 2007) and Sanofi-Synthelabo v. Apotex, Inc., 550 F.3d 1075 (Fed. Cir. 2008). In those cases, the Federal Circuit held that the prior art references did not enable a POSA to make substantially pure isomers (or enantiomers) of the drug compounds recited in the challenged patents. 501 F.3d at 1263; 550 F.3d at 1075. Here, however, the Board found that Ahmad, along with other references in the prior art, taught a POSA how to separate the (E)- and (Z)-isomers of endoxifen, and thus how to make a composition having 90 % pure (Z)-endoxifen. PGR2023-00043, Paper 37 at 21-31.

The Board also rejected Patent Owner’s argument that because “Ahmad does not contain any working examples of the synthetic method that result in a 90% pure (Z)-endoxifen,” the reference is not enabled. Id., 23. Rather, “as Petitioner note[d], the Federal Circuit does not require actual performance to be enabling.” Id. (citing Bristol-Myers, 246 F.3d at 1379). In addition, the Board agreed with Petitioner that two other references demonstrated that a POSA would have been enabled by Ahmad as of the effective filing date. Id., 20-25. While some of those references were published after Ahmad, Petitioner was allowed to rely on those references to demonstrate what was known by a POSA as of that effective filing date. Id.

The Board also rejected several additional technical and scientific arguments that Patent Owner presented, and briefly addressed the Wands factors. Id., 29-31. The Board concluded that “Patent Owner has not shown by a preponderance of the evidence that a POSA reading Ahmad would have been unable to make 90% pure (Z)-endoxifen.” Id., 29. Thus, because Ahmad enabled a POSA to make 90% pure (Z)-endoxifen (i.e., the free base form of (Z)-endoxifen), and because it disclosed every limitation of the challenged claims, those claims were found unpatentable as anticipated by Ahmad.

The claim phrase “the compound of Formula (III) is (Z)-endoxifen” construed as limited to the free base form of (Z)-endoxifen

Another important issue addressed in the Board’s decision was how to construe the claim phrase “the compound of Formula (III) is (Z)-endoxifen.” PGR2023-00043, Paper 37 at 10-13. The Board initially “construed sua sponte” this claim phrase in its Institution Decision because they “disagreed with Patent Owner’s argument that the phrase is limited to the free base form of (Z)-endoxifen.” Id., 10. Instead, the Board initially determined “that for purposes of the Institution Decision, the construction of ‘the compound of Formula (III) is (Z)-endoxifen’ includes the polymorphic, salt, free base, co-crystal and solvate forms of (Z)-endoxifen.” Id.

After post-trial briefing on this issue, requested by the Board “[d]uring trial,” the Board reversed course and held that “the intrinsic evidence supports construing the limitation ‘the compound of Formula (III) is (Z)-endoxifen’ to be limited to the (Z)-endoxifen free base form and excludes the salt and solvate forms.” Id., 10, 13. While the Board acknowledged that the specification broadly defines “the compound of Formula (III)” to encompass various forms of endoxifen (i.e., polymorphic forms, salts, etc.), “[t]he claim further narrows ‘the compound of formula (III)’ to ‘(Z)-endoxifen.’” Id., 12. And the Board explained that the question was “whether ‘(Z)-endoxifen’ should be construed broadly to include the free base and salt form or if it should be limited to its free base form.” Id.

The Board reasoned that “[w]hen read as a whole … the Specification consistently identifies (Z)-endoxifen salts as separate from (Z)-endoxifen.” Id., 13. Specifically, “the ’334 Patent refers to ‘(Z)-endoxifen and salts thereof,’ suggesting that references to ‘(Z)-endoxifen’ alone do not include the salt forms unless expressly identified as such.” Id. And the Board noted that the specification’s focus was on “preparations of endoxifen free base that are … at least 90% (Z)-endoxifen free base.” Id., 13 (emphasis added) (quoting ’334 patent at 83:43-45).

In view of “the language of the claims and the Specification as a whole,” the Board determined “that the intrinsic evidence supports construing the limitation ‘the compound of Formula (III) is (Z)-endoxifen’ to be limited to the (Z)-endoxifen free base form and excludes the salt and solvate forms.” Id.

III. Conclusion and Takeaways

The Board’s decision provides important guidance on several issues, most notably that a prior art patent must be enabling as of the earliest effective filing date of the challenged patent to serve as an anticipatory reference under AIA § 102. It is worth noting, however, that the Board implied that there may be situations under AIA § 102(b)(1), which “provides for a one-year grace period under certain circumstances,” in which an anticipatory reference may need to be enabled before the effective filing date of the challenged patent. Id., 19. Relatedly, the Board’s decision reaffirms that if a patent owner challenges whether an anticipation reference is enabled, the petitioner may rely on other references, including later-published references, to overcome the patent owner’s enablement challenge.

This decision also highlights the importance of claim construction in the context of patents that claim chemical compounds by structure and/or name. Indeed, whether a claim is limited to only the free base form of a compound (as was the case here) or if it also encompasses other forms of the compound (i.e., salts, polymorphs, etc.) can be critically important to both infringement and invalidity issues in litigation. While the Board determined that the ’334 patent was limited to the free base form of (Z)-endoxifen, it was admittedly a close call. Both patent prosecutors and litigators should review the Board’s decision here when considering whether a claimed chemical compound is limited to a particular form or if it more broadly encompasses multiple forms of the compound.

[1] Intas Pharms. Ltd. v. Atossa Therapeutics, Inc., PGR2023-00043, Paper 37 (PTAB Jan. 29, 2025)

[2] List of new drugs approved in the year 2019 till date. Central Drugs Standard Control Organization, Government of India. Available at: https:// cdsco.gov.in/opencms/resources/UploadCDSCOWeb/2018/ UploadApprovalNewDrugs/newdrugaapproaldec2019.pdf.

Patent Eligibility: The Call for Supreme Court Clarity and for an End to Summary Affirmances

The U.S. Supreme Court has once again been urged to revisit 35 U.S.C. § 101, the statute governing patent eligibility. Audio Evolution Diagnostics, Inc. (AED) filed a petition for writ of certiorari, challenging the Federal Circuit’s summary affirmance under Rule 36 of a ruling that invalidated its patents under the Alice/Mayo framework. Should the SCOTUS take up the case, this presents an opportunity for the Court to clarify the boundaries of patent eligibility and address concerns over the Federal Circuit’s handling of such cases.

AED’s Basis for its Petition

AED’s petition asserts that “the Federal Circuit remains at an impasse over the proper scope of § 101” and that the § 101 doctrine “is in chaos and requires this Court’s review.”

AED raises, inter alia, two key concerns: First, since Alice was decided more than a decade ago, “division among decisionmakers on how to correctly apply the two-step framework has dominated the jurisprudence.” And second, the Federal Circuit’s overuse of summary affirmances under Rule 36, and “whether the Federal Circuit can properly fulfill its § 101 interpretation role using just one word: ‘affirmed.’”

In support of the first key concern, AED asserts several issues: (i) the blending of subject matter eligibility under § 101 with other patentability requirements such as novelty and non-obviousness; (ii) the conflation of factual and legal questions, especially in step one of the analysis; and (iii) arbitrary outcomes caused by “the [Federal Circuit] judges’ differing opinions on § 101 and their decade-long reluctance to address the issue en banc.”

As to the second key concern, AED notes that the Federal Circuit’s use of Rule 36 to summarily affirm lower court decisions without issuing an opinion has been widely criticized. Particularly, AED asserts that the Federal Circuit’s one-word affirmance (“affirmed”) effectively shields the underlying decision from Supreme Court review. The lack of an opinion means there is no explanation of the legal reasoning, “leaving litigants to guess the reasoning behind the decisions.”

Why This Case Matters

Patent holders and accused infringers have asked for more certainty, and given the stakes, clarity is needed. AED’s petition is not the first time stakeholders have asked the Supreme Court to clarify the Alice/Mayo standard. The Solicitor General, courts, USPTO, and Congress have all requested clearer guidance from the SCOTUS on patent eligibility. Due to the lack of clear guidance from the courts, litigants regularly face the question of subject matter eligibility with limited ability to weigh likely outcomes. Even former members of he Federal Circuit itself have voiced concern. Retired Federal Circuit Chief Judge Michel wrote: “[N]ary a week passes without another decision that highlights the confusion and uncertainty in patent-eligibility law.”

Some observers have argued that uncertainty under § 101 stifles innovation, and that this uncertainty has far-reaching implications for innovators, investors, and businesses. Inconsistent rulings under Alice have led to unpredictability in outcomes, particularly in fields such as software, artificial intelligence, business methods, and medical diagnostics. The absence of clear, enforceable standards makes it difficult for companies to assess patentability, protect their innovations, and secure investments. In the words of retired Chief Judge Michel: “The result [of Section 101’s unpredictability], unavoidably, is less innovation. Why? Because all these commercial actors follow the simple caution: when in doubt, do not commit time and money in high-risk endeavors, which is what innovation always is.”

Rule 36 judgments provide no guidance to the parties, the lower courts or to the legal community in general. Worse, they provide no basis for Supreme Court review. These summary affirmances have increasingly come under scrutiny for their lack of transparency. Observers have argued that this practice undermines the Federal Circuit’s role in creating uniformity in patent law—a primary reason for its creation.

What Comes Next?

AED’s petition presents the Supreme Court with an opportunity to provide guidance and clarification on the Alice/Mayo framework and addressing the Federal Circuit’s use of Rule 36 in cases involving significant legal questions.

The Supreme Court’s response to this petition could have major implications for the future of patent eligibility in the U.S. If the Court declines to hear the case, the uncertainty surrounding § 101 jurisprudence will persist, at least for now, leaving some patent holders, accused infringers, legal practitioners and District Court’s to continue to ask for more predictability in securing, defending and weighing the eligibility of their patent rights.

Listen to this post