5 Key Takeaways | SI’s Downtown ‘Cats Discuss Artificial Intelligence (AI)

Recently, we brought together over 100 alumni and parents of the St. Ignatius College Preparatory community, aka the Downtown (Wild)Cats, to discuss the impact of Artificial Intelligence (AI) on the Bay Area business community.

On a blustery evening in San Francisco, I was joined on a panel by fellow SI alumni Eurie Kim of Forerunner Ventures and Eric Valle of Foundry1 and by my Mintz colleague Terri Shieh-Newton. Thank you to my firm Mintz for hosting us.

There are a few great takeaways from the event:

What makes a company an “AI Company”?

The panel confirmed that you cannot just put “.ai” at the end of your web domain to be considered an AI company.

Eurie Kim shared that there are two buckets of AI companies (i) AI-boosted and (ii) AI-enabled.

Most tech companies in the Bay Area are AI-boosted in some way – it has become table stakes, like a website 25 years ago. The AI-enabled companies are doing things you could not do before, from AI personal assistants (Duckbill) to autonomous driving (Waymo).

What is the value of AI to our businesses?

In the future, companies will be infinitely more interesting using AI to accelerate growth and reduce costs.

Forerunner, who has successfully invested in direct-to-consumer darlings like Bonobos, Warby Parker, Oura, Away and Chime, is investing in companies using AI to win on quality.

Eurie explained that we do not need more information from companies on the internet, we need the answer. Eurie believes that AI can deliver on the era of personalization in consumer purchasing that we have been talking about for the last decade.

What are the limitations of AI?

The panel discussed that there is a difference between how AI can handle complex human problems and simple human problems. Right now, AI can replace humans for simple problems, like gathering all of the data you need to make a decision. But, AI has struggled to solve for the more complex human problems, like driving an 18-wheeler from New York to California.

This means that, we will need humans using AI to effectively solve complex human problems. Or, as NVIDIA CEO Jensen Huang says, “AI won’t take your job, it’s somebody using AI that will take your job.”

What is one of the most unique uses of AI today?

Terri Shieh-Newton shared a fascinating use of AI in life sciences called “Digital Twinning”. This is the use of a digital twin for the placebo group in a clinical trial. Terri explained that we would be able to see the effect of a drug being tested without testing it on humans. This reduces the cost and the number of people required to enroll in a clinical trial. It would also have a profound human effects because patients would not be disappointed at the end of the trial to learn that they were taking the placebo and not receiving the treatment.

Why is so much money being invested in AI companies?

Despite the still nascent AI market, a lot of investors are pouring money into building large language models (LLMs) and investing in AI startups.

Eric Valle noted that early in his career the tech market generally delivered outsized returns to investors, but the maturing market and competition among investors has moderated those returns. AI could be the kind of investment that could generate those returns 20x+ returns.

Eric also talked about the rise of venture studios like his Foundry1 in AI. Venture studios are a combination of accelerator, incubator and traditional funds, where the fund partners play a direct role in formulating the idea and navigating the fragile early stages. This venture studio model is great for AI because the studio can take small ideas and expand them exponentially – and then raise the substantial amount of money it takes to operationalize an AI company.

Retailers: Questions About 2024’s AI-Assisted Invention Guidance? The USPTO May Have Answers

In February 2024, we posted about the USPTO’s Inventorship Guidance for AI-assisted Inventions and how that guidance might affect a retailer in New USPTO AI-Assisted Invention Guidance Will Affect Retailers and Consumer Goods Companies. With a year now having passed, it is likely you have questions about the guidance.

In mid-January 2025, the USPTO released a series of FAQs relating to this guidance that may answer certain questions. Specifically, there are three questions and responses in the FAQs. The USPTO characterized these FAQs as being issued to “provide additional information for stakeholders and examiners on how inventorship is analyzed, including for artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted inventions.” The USPTO further stated that “[w]e issued the FAQs in response to feedback from stakeholders. The FAQs explain that the guidance does not create a heightened standard for inventorship when technologies like AI are used in the creation of an invention, and the inventorship analysis should focus on the human contribution to the conception of the invention.” The FAQs appear to stem, at least in part, from written comments the USPTO received from the public on the guidance.

The FAQs serve to clarify key issues, including that:

1) there is no heightened standard for inventorship of AI-assisted inventions;

2) examiners do not typically make inquiries into inventorship during patent examination and the guidance does not create any new standards or responsibilities on examiners in this regard; and

3) there is no additional duty to disclose information, beyond what is already mandated by existing rules and policies.

A key statement by the USPTO in the FAQ responses is: “The USPTO will continue to presume that the named inventor(s) in a patent application or patent are the actual inventor(s).”

Regardless of whether the USPTO will (most likely) not make an inventorship inquiry during patent examination, IP counsel should still ensure that appropriate inventorship inquiries are made during the patent application drafting process. A best practice is to maintain all applicable records after drafting to support an inventorship inquiry, which may not come until after a patent issues, such as during litigation.

While the FAQs may not address all questions about the AI inventorship guidance, they are a step towards demonstrating how the USPTO will handle AI related patent issues moving forward.

Federal Circuit Highlights the Importance of Separating Claim Construction and Infringement Analysis When Dealing with After-Arising Technology

Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation v. Torrent Pharma Inc., No. 23-2218 (Fed. Cir. 2025) — On January 10, 2025, the Federal Circuit reversed the district court’s opinion that claims of a Novartis patent are invalid for lack of adequate written description, but affirmed the district court’s finding that the claims were not proven invalid for lacking enablement or being obvious over the asserted prior art. The Federal Circuit emphasized that the proper analysis for enablement and written description challenges is focused on the claims and after-arising technology need not be enabled or described in the specification—even when the after-arising technology is found to infringe the claims because the issues of patentability and infringement are distinct. “It is only after the claims have been construed without reference to the accused device that the claims, as so construed, are applied to the accused device to determine infringement.”

Background

Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation (“Novartis”) sued multiple defendants accusing them of infringing all claims (1-4) of U.S. Patent No. 8,101,659 (“the ’659 patent”) titled “Methods of treatment and pharmaceutical composition.” The ’659 patent relates to a pharmaceutical composition comprising a combination of valsartan and sacubitril, which Novartis markets and sells as a treatment for heart failure under the brand name Entresto®.

The U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware found that although the claims of the ’659 patent were not shown to be invalid as being obvious, indefinite, nor lacking enablement, the claims were shown to be invalid for lacking a written description. The district court “construed the asserted claims [of the ’659 patent] to cover valsartan and sacubitril as a physical combination and as a complex.” After claim construction, defendants MSN Pharmaceuticals, Inc., MSN Laboratories Private Ltd., and MSN Life Sciences Private Ltd. stipulated to infringement of the as-construed claims. However, the district court found that since complexes of valsartan and sacubitril (which included the accused product) were unknown to a person of ordinary skill in the art as of the priority date of the ’659 patent (i.e., the accused product was an after-arising technology), “Novartis scientists, by definition, could not have possession of, and disclose, the subject matter of such complexes . . . and therefore, axiomatically Novartis cannot satisfy the written description requirement for such complexes.”

Novartis appealed the district court’s determination of invalidity.

Issues

The primary issues on appeal were:

Whether the claims of the ’659 patent are invalid for lack of written description?

Whether the claims of the ’659 patent are invalid for lack of enablement?

Whether the claims of the ’659 patent are invalid as being obvious?

Holdings and Reasoning

1. The claims of the ’659 patent are not invalid for lack of written description.

The Federal Circuit found that the district court clearly erred in finding that the claims of the ’659 patent are invalid for lack of a written description. Specifically, the Federal Circuit found the district court erred when it “construed [the claims] to cover complexes of valsartan and sacubitril.” And the district court’s written description analysis under this construction to be incorrect with respect to complexes of valsartan and sacubitril.

The Federal Circuit noted that the issue is whether the ’659 patent describes what is claimed (i.e., a pharmaceutical composition comprising valsartan and sacubitril administered in combination). And that the issue is not whether the ’659 patent describes complexes of valsartan and sacubitril—because the ’659 patent does not claim complexes of valsartan and sacubitril. The Federal Circuit found that by stating the claims of the ’659 patent were “construed to cover complexes of valsartan and sacubitril,” the district court “erroneously conflated the distinct issues of patentability and infringement.” The Federal Circuit explained that “claims are not construed ‘to cover’ or ‘not to cover’ the accused product. . . . It is only after the claims have been construed without reference to the accused device that the claims, as so construed, are applied to the accused device to determine infringement.” The Federal Circuit found that “the ’659 patent could not have been construed as claiming [] complexes [of valsartan and sacubitril] as a matter of law” because it was undisputed that the accused product was unknown at the time of the invention.

The Federal Circuit found that since the district court gave the disputed claim term its plain and ordinary meaning during claim construction (i.e., “wherein said [valsartan and sacubitril] are administered in combination”), the ’659 patent need only to adequately describe combinations of valsartan and sacubitril to satisfy the written description requirement.

The Federal Circuit further found that the ’659 patent “plainly described [combinations of valsartan and sacubitril] throughout the specification” and that accordingly, the claims of the ’659 patent are not invalid as lacking a written description.

2. The claims of the ’659 patent are not invalid for lack of enablement.

The Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s ruling that the claims of the ’659 patent are not invalid for lack of enablement “for reasons similar to those that led us to reverse its written description determination: a specification must only enable the claimed invention.” The Federal Circuit found that “because the ’659 patent does not expressly claim complexes, and because the parties do not otherwise dispute that the ’659 patent enables that which it does claim . . . [the defendants] failed to show that the claims are invalid for lack of enablement.”

In affirming the district court’s ruling that the claims of the ’659 patent are not invalid for lack of enablement, the Federal Circuit agreed with the district court’s finding that “valsartan sacubitril complexes . . . are part of a ‘later-existing state of the art’ that ‘may not be properly considered in the enablement analysis.’”

3. The claims of the ’659 patent are not invalid as being obvious.

The Federal Circuit found “no clear error warranting reversal of the district court’s obviousness analysis” and thus affirmed the district court’s ruling that the claims of the ’659 patent are not invalid as being obvious. The Federal Circuit agreed that the district court’s rejection of the defendants’ two theories of obviousness: (1) that a person of ordinary skill in the art would have been motivated to modify a prior art therapy with valsartan and sacubitril to arrive at the claimed invention; and (2) that a person of ordinary skill in the art would have been motivated to individually select and combine sacubitril and valsartan from two different prior-art references to arrive at the claimed invention.

The Federal Circuit distinguished the cases defendants relied upon: Nalproprion Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Actavis Laboratories FL, Inc., 934 F.3d 1344 (Fed. Cir. 2019) and BTG International Ltd. v. Amneal Pharmaceuticals LLC, 923 F.3d 1063 (Fed. Cir. 2019). The Federal Circuit reasoned that in Nalproprion and Actavis, the prior art showed that the claimed drugs “were both together and individually considered promising . . . treatments at the time of the invention.” In contrast, the district court found that “there was no motivation in the relied-upon prior art to combine valsartan and sacubitril, let alone with any reasonable expectation of success.”

The Federal Circuit agreed “with the district court that [the defendants’] obviousness theories impermissibly use valsartan and sacubitril as a starting point and ‘retrace[] the path of the inventor with hindsight.’”

Listen to this post

USPTO Scam: A Warning to Trademark Owners

As we warned in December 2023, multiple trademark owners have contacted Blank Rome to say that, in a renewed fraud, scam artists have contacted them by telephone pretending to be the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”). The scam artists claim to be from the USPTO (e.g., from the USPTO’s Accounts Receivable division, sometimes even displaying their caller ID), and seek credit card payment for fees related to trademarks and trademark applications.

This request is a fraud and if any fees are due, rest assured—if Blank Rome is your representative for such trademark work—we are handling the matter directly with the USPTO. The USPTO does not contact represented trademark owners directly. If you receive any such phone call, hang up immediately (or do not answer) and refrain from any discussion or disclosure whatsoever. If you believe you have already given your credit card information to a fraudster, immediately contact your credit card company to cancel the card and obtain a new one.

Please visit the USPTO website for more information on scams and protecting yourself from scams: Caution: Scam alert | USPTO.

Beijing Higher People’s Court Affirms Win for Belgian Artist Christian Silvain in Copyright Suit Against Sichuan Academy of Fine Arts Professor

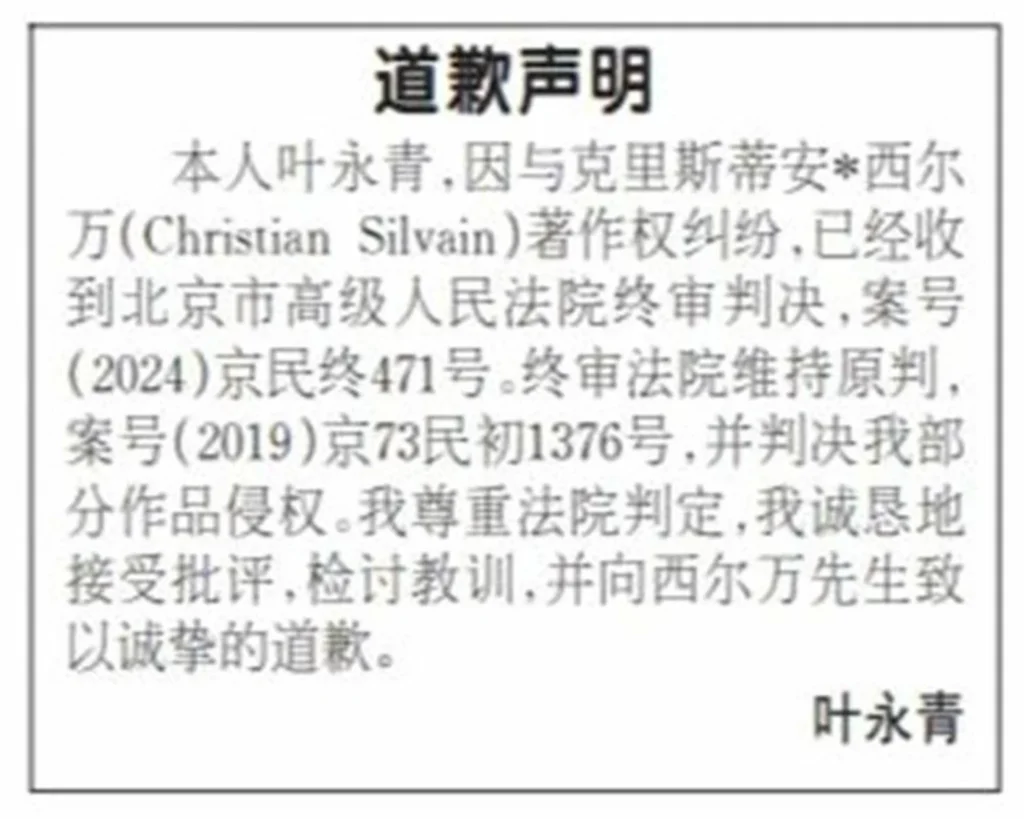

Marking the conclusion of a long legal battle, the Beijing Higher People’s Court recently affirmed an August 24, 2023 decision by the Beijing IP Court against Sichuan Academy of Fine Arts Professor Ye Yongqing. The Beijing IP Court ruled that Ye infringed the copyright of Silvain in his paintings and ordered Ye to pay Silvain 5 million RMB, publish an apology and cease infringement. That apology was published in China’s Legal Daily on January 23, 2025.

Ye Yongqing’s public apology to Belgian painter Christian Silvain for plagiarizing his artworks.

Left: Artwork by Silvain in 1990. Right: Artwork by Ye from 1994.

The apology reads,

I, Ye Yongqing, have received the final judgment of the Beijing Higher People’s Court for the copyright dispute with Christian Silvain, case number (2024) 京民众471号。 The appeals court upheld the original judgment, case number (2019) 京73民初1376, and ruled that some of my works infringed. I respect the Court’s judgment, sincerely accept the criticism, review the lessons, and sincerely apologize to Mr. Silvain.

I have been unable to locate the appeals decision but a copy of the ruling from the Beijing IP Court courtesy of 书法订阅 is available here (Chinese only).

China’s State Council Releases Antitrust Guidelines for the Pharmaceutical Sector Covering Reverse Payments and Evergreening

In follow up to the State Administration for Market Regulation’s (SAMR) draft of August 9, 2024, China’s State Council has released the final version of the Antitrust Guidelines for the Pharmaceutical Sector (国务院反垄断反不正当竞争委员会关于药品领域的反垄断指南) on January 24, 2025. Of specific interest to patentees are the regulations on reverse payments and evergreening, translations of which follow. The existence of patents can also used in the determination of a dominant market position.

Article 13 Reverse Payment Agreement

There is an actual or potential competition relationship between the patent holder of the generic drug and the generic drug applicant. If the patent holder of the generic drug gives or promises to give direct or indirect benefit compensation to the generic drug applicant without justifiable reasons, and the generic drug applicant makes a reverse payment agreement with non-competition commitments such as not challenging the validity of the patent right related to the generic drug, delaying entry into the market related to the generic drug, or not selling generic drugs in a specific region, it may constitute a monopoly agreement prohibited by Article 17 of the Anti-Monopoly Law.

To analyze whether a reverse payment agreement constitutes a monopoly agreement, the following factors may be considered:

(1) Whether the compensation given or promised by the patent owner of the generic drug to the generic drug applicant obviously exceeds the cost of resolving disputes related to the generic drug patent and cannot be reasonably explained;

(2) Whether the agreement substantially prolongs the market exclusivity period of the generic drug patent holder or hinders or affects the entry of generic drugs into the relevant market;

(3) Other factors that exclude or restrict competition in the relevant market.

Article 27 Other acts of abuse of dominant market position [Evergreening]

If a pharmaceutical operator purchases goods at unfairly low prices, sells goods at prices below cost, or engages in other abuses of market dominance as determined by the anti-monopoly law enforcement agency of the State Council, the analysis will be based on Chapter III of the Anti-Monopoly Law and the Provisions on Prohibition of Abuse of Market Dominance.

If a drug patent holder with a dominant market position obtains new drug patents by redesigning existing patented technical solutions and adopts measures such as stopping sales and repurchasing to achieve product switching from original patented drugs to new patented drugs, thereby hindering generic drug operators from effectively competing, it may constitute an abuse of market dominance prohibited by Article 22, paragraph 1, item 7 of the Anti-Monopoly Law.

To analyze whether product redirection behavior constitutes an abuse of market dominance, the following factors may be considered:

(1) Whether the new patented drug fails to significantly improve the drug’s use or efficacy, or significantly enhance the drug’s safety, etc.;

(2) When implementing the conversion from the original patented drug to the new patented drug, whether the relevant business operator has planned to launch a generic drug;

(3) Whether the conversion of the original patented drug to the new patented drug hinders or affects the entry of generic drugs into the relevant market or their effective competition;

(iv) whether the range of choices for patients and physicians will be substantially restricted;

(5) Whether there are legitimate reasons.

The full text is available here (Chinese only).

What in the [Meta]World?: Abitron Creates More Questions than Answers

At a glance, a unanimous Supreme Court, holding that two provisions of the trademark-governing Lanham Act (15 U.S.C. §§ 1114(1)(a) and 1125(a)(1)) do not apply extraterritorially and extend only to alleged infringement in domestic commerce, does not appear groundbreaking. Nor does it appear to have any effect on the metaverse. Yet, the two worlds do collide, and the courts and legislature will need to consider extra-tangible applications more frequently at a time in history when virtual reality is just a couple clicks away.

Numerous Supreme Court decisions have reached the same conclusion as Abitron Austria GmbH et al v. Hetronic International, stressing the importance of the “presumption against extraterritoriality,” and reasoning that the laws of the United States should not reach too far abroad. Similarly, preceding decisions have used the same two-step framework applied in this case to evaluate the extraterritorial reach of a statute and to determine if the case merits any redress, asking first (1) whether the statute at issue clearly and affirmatively rebuts the presumption against extraterritoriality; and if not, (2) asking whether the case involves a domestic application of the statute. If step two uncovers a domestic infringement of rights covered by the disputed statute, then there is potential that the alleged harm may be remedied.

Nine justices concluding that the Lanham Act does not reach extraterritorially, and treading a well-worn path to get there, should provide a rather ho-hum decision, right?

Not quite.

Context: Facts of the Case

Hetronic International, Inc., a U.S. company, contracted with six foreign parties (Abitron Austria GmbH, et al.) to distribute Hetronic’s products, mostly in Europe. The relationship deteriorated when Abitron decided that it, not Hetronic, owned the rights to Hetronic’s trademarks and other intellectual property. Abitron began manufacturing products identical to Hetronic and selling those products under the Hetronic brand. Hetronic terminated the contractual relationship, but Abitron continued to manufacture and sell the lookalike products. Hetronic sued in federal district court under the Lanham Act and won approximately $96 million and a worldwide injunction. On appeal, the trial court’s decision was affirmed.

Abitron turned to the Supreme Court in hopes of a different result, and presented the question: does the Lanham Act permit the owner of a U.S.-registered trademark to recover damages for the use of that trademark when the infringement occurred outside the United States and is not likely to cause confusion in the United States?

A Split Unanimity

Justice Alito’s majority opinion was the majority by a margin of just one justice, teaming up with Justices Kavanaugh, Gorsuch, Thomas, and Jackson. Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Kagan and Barret joined Justice Sotomayor’s concurrence in the result. So, the “unanimity” factor here appears more strained than a typical 9-0 result. While the two sides reached the same conclusion, the paths taken to get there vigorously differed.

Both sides agreed at step one of the extraterritoriality two-step: the Lanham Act does not clearly and affirmatively rebut the presumption against extraterritoriality, therefore, it should not apply abroad.

At step two, however, the iceberg split. Justice Alito’s slight majority understood step two to focus solely on whether infringing “conduct” had occurred in domestic commerce within the United States. The slim majority subscribed to a conduct-based approach at step two because, when a claim involves “both domestic and foreign activity, the question is whether ‘the conduct relevant to the statute’s focus occurred in the United States.’”

In other words, after determining a statute’s focus, Alito argued that courts should determine whether actual activity relevant to the statute’s focus occurred within the defined bounds of United States territory. If the activity occurred outside the United States, courts could end their analysis; at that point, the case could be presumed extraterritorial and out of reach of the statute(s) governing the lawsuit.

Again, in the majority’s understanding, location of conduct, and not the location of the resulting confusion or lost profits, dictates whether any claims should be classified as extraterritorial or domestic.

The majority reasoned that the relevant conduct alleged in Abitron, under the trademark-focused Lanham Act, was infringing use of a trademark in commerce. Whether that conduct fell within or outside of the bounds of the United States would be a question returned to the lower courts to unravel based on the conduct-focused understanding of the extraterritoriality two-step. Because the Abitron proceedings in the lower courts were not in accord with the majority’s interpretation of extraterritoriality, they were vacated; and while the majority did not definitively describe when an infringing use in commerce of a trademark occurs in a U.S. territory, it remanded the case for the lower courts to figure it out.

While in agreement with the result, Justice Sotomayor’s concurrence argued that step two actually requires more than an analysis of mere conduct in the United States, which she believed too narrow a divining rod. Rather, it was the concurrence’s impression that step two should be based on a contextual likelihood of confusion test to determine whether activities, either at home or abroad, could induce consumer confusion in the United States.

In contrast to the majority’s conduct-based approach, Justice Sotomayor provided a focus-based approach: which interests were Congress’s focus when it enacted a statute, which parties did it intend to protect, and where were those parties and interests located? Instead of focusing on just the relevant conduct, the minority concurrence would have a court consider whether, under the Lanham Act, the alleged infringement created a likelihood of consumer confusion in the United States, regardless of where that alleged infringement occurred.

Justice Sotomayor’s minority accused Justice Alito’s conduct-based approach of adding a third step to the two-step framework which “frustrates” Congress’s goal to legislate with predictability, especially in the case of protecting U.S. trademark owners and consumers. Justice Sotomayor believed Justice Alito completely ignored the accepted second step—looking to the statute’s focus, regardless of whether its focus goes to or beyond conduct—and conjured up an unprecedented assessment of whether conduct, and solely conduct, relevant to the statute’s focus, occurred domestically. To Justice Sotomayor, this “novel approach” contradicted years of Supreme Court jurisprudence because the Court “has expressly recognized that a statute’s ‘focus’ can be ‘conduct,’ ‘parties,’ or ‘interests’ that Congress sought to protect and regulate.”

To majority’s main gripe with Justice Sotomayor’s concurrence was how broadly she would interpret the second step of the extraterritoriality framework. “Use in commerce,” Justice Alito wrote, “provides the dividing line between foreign and domestic applications of [the Lanham Act],” and shifting the relevant inquiry, as Justice Sotomayor would, to a “focus-only standard . . . that any claim involving a likelihood of consumer confusion in the United States would be a ‘domestic’ application of the Act . . . . is wrong.” The majority felt that the minority’s approach resisted a straightforward application of precedential extraterritoriality framework and would “create headaches for lower courts.”

Interestingly, although part of the majority, Justice Jackson wrote her own concurring opinion that spun “conduct” and “use in commerce” in a more expansive way than perhaps either Justices Alito or Sotomayor considered. To Justice Jackson, even though she ascribed to the majority’s conduct-focused approach, “a ‘use in commerce’,” read “conduct,” “does not cease at the place the mark is first affixed, or where the item to which it is affixed is first sold. Rather, it can occur wherever the mark serves its source-identifying function.” Citing Jack Daniel’s Properties, Inc. v. VIP Products LLC, another trademark case, Justice Jackson explained that a trademark is a trademark under the Lanham Act when it serves as a source identifier, distinguishing goods from those manufactured and sold by competitors. She emphasized that the Lanham Act defines commerce as “the bona fide use,” again, “conduct,” “of a mark in the ordinary course of trade,” which, to her, could occur “wherever the mark serves its source-identifying function”—whether that is in its country of origin, or elsewhere, even many times removed from the first sale. “If a marked good is in domestic commerce, and the mark is serving a source-identifying function in the way Congress described,” the trademark receives protection under the Lanham Act. Conversely, “if the mark is not serving that function in domestic commerce, then the conduct Congress cared about is not occurring domestically.” This understanding of conduct, particularly related to trademarks, appears to combine the Justice Alito approach (domestic conduct only) and the Justice Sotomayor approach (infringing conduct, activity, focus, or interests originating outside the United States can still have domestic implications).

Enter: The Metaverse

In a world where reality transcends tangible commerce that moves from point A to B on boats, trains, and airplanes, the question presented in future extraterritoriality cases, trademark-related or not, is going to be forced to consider where conduct takes place—both in- and outside of tangible reality.

This burgeoning understanding of extraterritoriality received hints in Abitron: both Justices Sotomayor and Jackson exhibited concern about how Abitron might affect internet commerce, and each dedicated a footnote to thinking about the online use of trademarks. Justice Jackson suggested that use “in commerce,” “in the internet age,” may very well include “a mark serving its critical source-identifying function in domestic commerce even absent the domestic physical presence of the items whose source it identifies.” Justice Sotomayor referenced “today’s increasingly global marketplace, where goods travel through different countries, [and] multinational brands have an online presence,” to argue that the majority’s conduct-only approach limits the Lanham Act to “purely domestic activities,” which results in “trademarks [that] are not protected uniformly around the world, . . . leav[ing] U. S. trademark owners without adequate protection.”

While the casual observer would do well to appreciate gestures toward the internet in any Supreme Court decision, technology has already leapt far beyond online storefronts. In a world of ChatGPT and MetaBirkins, the general “internet” is only the beginning. Source-identifying trademarks may appear far deeper in the wrinkles of cyberspace.

The metaverse, being neither foreign nor domestic, provides unique problems for a piece of legislation, like the Lanham Act, originally written generations before the concept of dial-up. Yes, a user might access the internet from the United States, but once that user hops into the metaverse, there are not necessarily any helpful geographical moorings that a court can easily define as foreign or domestic because there is no real “conduct” occurring—in the metaverse, avatars run by algorithms and code do the interacting, and while they are doing, does a statute yet exist that covers virtual doings in a virtual world? Should a statute cover such dealings? Should an extraterritoriality statute do the heavy lifting here? If one applies the majority approach, where does conduct occur in a metaverse scenario? Maybe only virtual reality users accessing virtual reality in a United States territory will be on the hook. In the minority application, maybe those outside U.S. territories can still be prosecuted if their actions affect virtual reality users accessing virtual reality inside a U.S. territory.

Location, however, provides only the starting point for a metaverse inquiry. As mentioned above, what exactly constitutes “conduct” when one takes part in business as a virtual avatar? Is intangible activity also “conduct” as recognized by the Lanham Act or other statutes? Furthermore, the fact that Abitron included three different interpretations of what could constitute foreign trademark use adds another wrinkle to the metaverse inquiry because the Court has yet to nail down a meaning in the real world. Which interpretation would be most useful going forward? Does Justice Jackson’s incredibly broad definition of “use in commerce” scratch the metaverse itch that commerce within virtual reality presents? Does Justice Alito’s conduct-focused approach transcend the tangible world—and how would/should he, and we, define extraterritoriality in a place that operates on servers where the physical location isn’t germane to anything? Would Justice Sotomayor’s consumer confusion test be the most workable solution for a world where reality can be more virtual than ever before, linking a visitor in the metaverse to a geographical location?

Abitron, albeit based on tangible goods traded across real borders, shines an uncomfortably glaring light on how slowly American jurisprudence plods along in relation to lightning-quick tech updates. The questions above are what make Abitron so intriguing, however, and will have to remain unanswered for a little while longer.

Two-Minute Drill: Department of Education Guidance and Department of Justice Weigh in on House Settlement

Change is inevitable. This sentiment resonates across the college sports landscape. Few, if any, would argue that the current model of college athletics is sustainable. While fans continue to tune in and March Madness remains a cornerstone of excitement, the line between amateurism and professionalism in college sports has grown increasingly blurry since July 2021.

As the fallout continues from the potential settlement of an antitrust class-action lawsuit filed against the NCAA — providing for nearly $2.8 billion in backpay to former athletes — new guidance from the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights and a Statement of Interest from the Department of Justice may disrupt the approval and impacts of the settlement, as well as the immediate future of college sports. The new DOE guidance warns NCAA schools that name, image, and likeness (NIL) payments must be distributed in a nondiscriminatory manner, pursuant to Title IX regulations. Meanwhile, the DOJ’s statement objects, among other things, to the settlement’s 22% cap on revenue sharing, citing concerns over antitrust violations since the cap was not collectively bargained.

With the potential final approval of the House v. NCAA settlement on the horizon, a hearing is set for April 7, 2025, rampant claims of transfer portal tampering, and headlines about college athletes signing deals rivaling NFL rookie contracts, the call for a solution to this largely unregulated system is louder than ever. Proposals for a “new model” are making headlines, but without fundamental legal and organizational changes, any attempts to fix college sports’ NIL system are as futile as us trying to guard Cooper Flagg at the top of the key — doomed to fail.

Under the proposed settlement in House v. NCAA, which has been preliminarily approved, in addition to the nearly $2.8 billion in backpay to Division I athletes who competed from 2016 to the present, a 10-year revenue-sharing plan would allow NCAA conferences and their member schools to share 22% of annual revenue with student-athletes. The settlement would establish a salary cap framework, in which schools would initially be able to pay their athletes up to $22 million annually.

Title IX

The new fact sheet from the Department of Education, released on January 16, 2024, may impose new guardrails on how the proposed revenue-sharing plan is implemented. The department’s guidance states that the department considers NIL compensation provided by a school as “athletic financial assistance.” Under Title IX, schools must provide equal athletic opportunity, regardless of sex, including “athletic financial assistance” awarded to student-athletes. The department further stated: “The fact that funds are provided by a private source does not relieve a school of its responsibility to treat all of its student-athletes in a nondiscriminatory manner [and it] is possible that NIL agreements between student-athletes and third parties will create similar disparities and therefore trigger a school’s Title IX obligations.”

Whether or not the new guidance from the Department of Education will significantly impact the distribution of the payments under the House v. NCAA settlement, with objections to the settlement due at the end of January, remains an open question. Jeffrey Kessler, an attorney for one of the plaintiffs in the class action, said that the guidance “has no impact on the settlement at all.” Instead, “the injunction does not require the schools to spend the new compensation and benefits that are permitted to any particular group of athletes and leaves Title IX issues up to the schools to determine what the law requires. [The House v. NCAA case] resolved antirust claims — not Title IX claims.”

Additionally, the timing of the new guidance, only days before the beginning of President Donald Trump’s new administration, may also influence how long the fact sheet will be relevant, if at all. Gabe Feldman, a professor of sports law at Tulane, stated that “the timing does call into question the impact this is going to have, because it is likely, as in a number of areas of law, that a new administration will reverse, rescind, amend, or completely change the guidance.” Indeed, the guidance itself states that the fact sheet “does not have the force and effect of law” and is “not meant to be binding” beyond what is required by actual law. Finally, in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo last year, overruling the Chevron doctrine that required courts to defer to agency interpretation of ambiguous statutes, the new guidance will likely have an even less binding effect.

The new guidance, released just days before the beginning of a new presidential administration, implies that schools may face risks under Title IX with the distribution of NIL payments, even if third parties or collectives are providing the funds. However, with a new administration, the position of the DOE could change resulting in even more uncertainty.

Cap on Revenue Sharing

The DOE was not the only government agency to raise concerns over the proposed House settlement. In a Statement of Interest filed on January 17, the DOJ raised objections surrounding the proposed settlement’s 22% cap on revenue sharing. The DOJ argues that the cap “functions as an artificial cap on what free market competition may otherwise yield” and raises “important questions about whether the settlement is fair, reasonable, and adequate.” The DOJ argues that even though the settlement would increase the cap on NIL payments from zero to $22 million, “the new amount is still fixed by agreement among organizations that collectively control the entire labor market.” Additionally, the DOJ objects to arguments that the revenue share cap is similar to caps imposed in professional sports leagues. The DOJ argues that salary caps in professional sports leagues were collectively bargained, which are generally immune from antitrust scrutiny. In this case, however, the 22% cap was not collectively bargained, and the proposed settlement was negotiated without college athletes benefiting from the substantive and procedural rights afforded to workers during collective bargaining.

The DOJ is also concerned that the proposed settlement could be used by the NCAA and power conferences as a defense in future antitrust cases. The DOJ has asked the court to either decline to approve the settlement or make it clear that the approved salary cap does not constitute a judgment on its competitive impact or that it complies with antitrust laws. Effectively, the DOJ has asked the court to either decline to approve the settlement or allow future litigants to file antitrust claims regarding the cap.

In order to approve the settlement, Judge Claudia Wilken, the presiding judge over the House case, must assess whether the settlement is fair, reasonable, and adequate. It remains to be seen whether Wilken will follow the DOJ’s requests. Regarding the settlement being used as a defense, the proposed settlement has certainly not dissuaded litigants from filing antitrust actions against the NCAA. Even after preliminary approval, at least two college athletes brought antitrust claims against the NCAA — a trend that is likely to continue, even if the settlement is granted final approval. The timing of the Statement of Interest is also notable, as it was filed mere days before Trump was sworn into office. The new administration might not align with the previous DOJ’s position, but the timing of confirmation hearings could delay any retraction or opposing opinion prior to the April 7th hearing.

Schools and athletes alike should continue to closely monitor the progress of the House v. NCAA settlement, as well as potential changes or rollbacks from the new administration that would affect distribution of the settlement payments and the proposed new revenue-sharing plan. With so much uncertainty surrounding college sports, schools are navigating uncharted waters, trying to maintain a competitive edge. Without a clear picture of the future, any decisions may feel like walking a tightrope — one wrong move could lead to success or setback.

Untwisting the Fixation Requirement: Flexible Rules on Moveable Sculptures

The US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit reversed and remanded a district court’s dismissal of a claim of copyright infringement for kinetic and manipulable sculptures, finding that movable structures were sufficiently “fixed” in a tangible medium for copyright purposes. Tangle, Inc. v. Aritzia, Inc., et al., Case No. 23-3707 (9th Cir. Jan. 14, 2024) (Koh, Johnstone, Simon, JJ.)

Tangle, a toy company, holds copyright registrations for seven kinetic and manipulable sculptures, each made from 17 or 18 identical, connected 90-degree curved tubular segments. These sculptures can be twisted or turned 360 degrees at the joints, allowing for various poses. Aritzia, a lifestyle apparel brand, used similar sculptures in its retail store displays, leading Tangle to file a lawsuit alleging copyright and trade dress infringement. Aritzia’s sculptures were larger, were a different color, and had a chrome finish.

The Copyright Act requires that a work of authorship be “fixed in any tangible medium of expression.” 17 U.S.C. § 102(a). At the pleading stage, the district court concluded that the sculptures were not fixed and thus dismissed Tangle’s copyright claim. The district court also dismissed the trade dress claim for failure to provide adequate notice of the asserted trade dress. Tangle appealed.

While the Ninth Circuit agreed with the district court’s dismissal of the trade dress claim, it disagreed with the district court’s ruling on the copyright claim. Comparing the kinetic, movable sculptures to music, movies, and dance, the Court found that Tangle’s dynamic sculptures were entitled to copyright protection and that Tangle adequately alleged valid copyrights in its sculptures. The Court held that the works’ ability to move into various poses did not, by itself, support the conclusion that they were not “fixed” in a tangible medium for copyright purposes.

The Ninth Circuit held that under the “extrinsic test” test, which looks at “the objective similarities of the two works, focusing only on the protectable elements of the plaintiff’s expression,” as set forth in the Court’s 2018 decision in Rentmeester v. Nike, Tangle plausibly alleged copying of its protected works by alleging that the creative choices it made in selecting and arranging elements of its copyrighted works were substantially similar to the choices Aritzia made in creating its sculptures.

Since Aritzia failed to dispute that Tangle had properly alleged copying, the Ninth Circuit stated that Tangle only needed to show that the sculptures were substantially similar to prove infringement. Applying its 2004 decision in Swirsky v. Carey, the Ninth Circuit explained that “substantial similarity can be found in a combination of elements, even if those elements are individually unprotected.”

The Ninth Circuit found that the copyrighted and accused sculptures were similar enough to the ordinary observer to constitute infringement because both were comprised of identical, connected 90-degree curved tubular segments that could be twisted and manipulated to create many different poses. The Court further explained that the vast range of possible expressions could afford the sculptures broad copyright protection.

This article was authored by Hannah Hurley

Be Wary: Sophisticated Scam Emails Impersonating IP Attorneys

Business owners should be aware of a new email scam circulating impersonating an intellectual property (IP) representative, containing false information, and offering trademark assistance. This nefarious email scam is sent by an operator impersonating a known Australia registered patent and/or trade mark attorney to garner legitimacy. IP Australia has provided an example of the scam and both IP Australia and the Institute of Patent and Trade Mark Attorneys (IPTA) continue to publish alerts regarding this issue.

Thousands of Australians fall victim to email scams each year. In April 2024, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) reported a 64.8% increase in email scams1 between 2022-2023. IP owners are not immune, often receiving misleading renewal notices sometimes causing payment of unnecessary fees to scammers that do not result in renewal of a trademark.

In an already email heavy environment, it is prudent to exercise a healthy level of caution about emails and correspondence sent from an unknown or new external email address. Be aware of these characteristics often associated with fraudulent emails:

A sense of urgency that require immediate action on behalf of the recipient;

Typographical errors and incorrect grammar; and/or

The sender’s email address may be like a legitimate email address but with a letter missing or added.

Any correspondence that claims to be associated with a government department such as IP Australia or a foreign trade mark registry should be considered carefully. Business owners should also train staff to recognise false invoices and renewal notices.

As we have previously reported here, encouragingly some jurisdictions are prosecuting these sophisticated criminals by imposing significant fines and imprisonment for their fraudulent trade mark renewal schemes. However, scammers are increasingly prevalent, and it is far less costly to prevent a scam, than to remedy one.

Footnotes:

1 Targeting scams: Report of the National Anti-Scam Centre on scams activity 2023 (Report no.1 April 2024) 15.

A Lynk to the Past: Published Applications Are Prior Art as of Filing Date

The US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit affirmed a Patent Trial & Appeal Board decision finding challenged claims invalid based on a published patent application that, in an inter partes review (IPR) proceeding, was found to be prior art as of its filing date rather than its publication date. Lynk Labs, Inc. v. Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd., Case No. 23-2346 (Fed. Cir. Jan. 14, 2025) (Prost, Lourie, Stark, JJ.)

Samsung filed a petition for IPR challenging claims of a Lynk Labs patent. Samsung’s challenge relied on a patent application filed before the priority date of the challenged patent. However, the application was not published until after the priority date of the challenged patent. The Board rejected Lynk Labs’ argument that the application could not serve as prior art and determined the challenged claims to be unpatentable. Lynk Labs appealed to the Federal Circuit, raising three arguments.

Lynk Labs’ first argument was that the application could not serve as prior art because the publication date meant that it was not publicly available until after the priority date of the challenged patent. Pre-America Invents Act (AIA) law applied. Lynk Labs cited 35 U.S.C. § 311(b), restricting IPR petitioners to challenges “on the basis of prior art consisting of patents or printed publications.” While Lynk Labs admitted that the published application was a printed application, it denied that it was a prior art printed publication.

The Federal Circuit reviewed the issue de novo as a question of statutory interpretation. The Court noted that §§ 102(e)(1) and (2) carve out a different rule for published patent applications than the test for §§ 102(a) and (b) prior art. Under the statute, a patent application filed in the United States before an invention claimed in a later filed application qualifies as prior art if the application is published or a patent is granted on it.

Lynk Labs did not dispute that, under § 102(e)(2), an application resulting in an issued patent can be prior art, even if the patent is granted after an invention’s priority date, as long as the application is filed before the challenged invention priority date. However, Lynk Labs took issue with the fact that the Board applied the same principle, under § 102(e)(1), to applications that are published but do not become patents.

The Federal Circuit explained that the plain language of the statute permitted IPR challenges based on such applications and rejected Lynk Labs’ arguments that the statute should be interpreted differently. Lynk Labs argued that when Congress enacted § 311(b), it transplanted the term “printed publications” from case law, along with that case law’s “old soil” that established that the application would not be prior art.

In support of its argument, Lynk Labs cited case law that in its view suggested that patent applications are never prior art printed publications. However, the Federal Circuit distinguished those cases on the basis they were decided at a time before applications were published and therefore did not address published applications. Lynk Labs also argued that because the “old soil” required public accessibility, it excluded applications. The Court rejected this argument as well. While the Court agreed with the “old soil” definition of “printed publications,” the Court explained that the definition includes published patent applications, since the latter are publicly accessible, thus confirming that “published patent applications qualify as ‘printed publications.’”

Finally, Lynk Labs argued that the term “printed publication” carries its own temporal requirement. The Federal Circuit rejected this argument, noting that it would create inconsistency in § 102. The Court determined that treating a published application like the one at issue here as prior art is consistent with the congressional purpose of restricting reexamination to printed documents because they do not require the substantial discovery of sale or public use and are a type of reference “normally handled by patent examiners.”

Vimeo’s Fleeting Interaction With Videos Doesn’t Negate Safe Harbor Protections

The US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit affirmed a district court’s decision, granting Vimeo qualified protection under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) safe harbor provision. Capitol Records, LLC v. Vimeo, Inc., Case Nos. 21-2949(L); -2974(Con) (2d Cir. Jan. 13, 2025) (Leval, Parker, Merriam, JJ.) This case addresses, for the second time, whether Vimeo had “red flag knowledge” of the defendant’s copyrighted works under the DMCA.

DMCA Section 512(c) provides a safe harbor that shelters online service providers from liability for indirect copyright infringement on their platforms under certain conditions. Congress provided two exceptions that would remove the safe harbor protection:

Actual or red flag knowledge of infringing content

The ability to control content while receiving a financial benefit directly attributable to the accused infringement activity.

EMI, an affiliate of Capitol Records, vehemently opposed Vimeo’s inclusion of videos containing EMI’s music on its site and initiated the present suit in 2009. The district court granted summary judgment in favor of Vimeo, dismissing the plaintiffs’ claims on the ground that Vimeo was entitled to the safe harbor protection provided by Section 512(c). EMI appealed.

In a 2016 appeal (Vimeo I ), the Second Circuit considered Vimeo’s activities under the DMCA. In Vimeo I, the Court (in the context of an interlocutory appeal) ruled that the copyright holder must establish that the service provider (e.g., Vimeo) had “knowledge or awareness of infringing content,” and that the service provider bore the initial burden to prove it qualified for the DMCA safe harbor, whereupon the burden shifted to the copyright holder to prove a disqualifying exception.

Knowledge of Infringement

In Vimeo I, the Second Circuit cited its 2012 decision in Viacom Int’l v. You Tube and explained that red flag knowledge incorporates an objective standard. The facts actually known to the service provider must be sufficient such that a reasonable person would have understood there to be infringement that was not offset by fair use or a license. Vimeo I clarified that service provider employees who are not experts in copyright law cannot be expected to know more than any reasonable person without specialized understanding.

The Second Circuit explained that this knowledge analysis is a fact-intensive one, and that copyright owners cannot rely on service provider employees’ generalized understanding to prove red flag knowledge for any video (or other work). The Vimeo I court also noted that the DMCA did not place a burden on service providers to investigate whether users had acquired licenses. In Vimeo I, the Second Circuit further instructed that because the legal community cannot agree on a universal understanding of fair use, it would be unfair to expect “untutored” service provider employees to determine whether a given video is not fair use on its face.

Right and Ability to Control

In analyzing what constitutes the right and ability to control, the Second Circuit emphasized that Congress’ purpose behind the DMCA was to effect a compromise between rightsholders and safe harbor claimants: “Congress recognized that the creation of websites on which the public could post videos would render a hugely valuable public service. However, the expense of either policing all postings to weed out infringements or of paying damages for infringements by users would be prohibitive.” Congress therefore gave rightsholders “limited recourse against service providers that have the ‘right and ability to control’ infringements by users, which our court has interpreted to apply in circumstances when the service provider has exercised ‘substantial influence’ over user activities.”

While Vimeo employees did not take part in the videos’ creation, they interacted in some way with each video at issue, such as by liking, commenting, promoting, or curating.

The Second Circuit concluded that Vimeo’s actions “were far less extensive as to both coercive effect and frequency” compared to past cases involving substantial influence. Promoting or liking certain videos is not restrictive or coercive and occurred with regard to only a small proportion of the site’s videos. Banning videos pursuant to community guidelines also does not qualify as control because the process furthers validated platform purposes: removing illegal videos and curating a platform for users “with particular interests.”

Taylor MacDonald also contributed to this article.