How to File a Letter of Protest in Trademark Cases

Filing a letter of protest is a proactive approach to show disagreement with the potential registration of a trademark. Such a letter is a document that can be sent to the trademark examiner to inform them of the grounds for refusing to register a certain trademark. In this article, we will discuss who can file […]

Designers Beware: Prior Utility Patent Lacking Written Support Can Anticipate Later-Filed Design Patents

In its recent In re Floyd opinion, the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit upheld a decision by Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) to reject a design applicant’s priority claim to an earlier utility filing for failing to adequately support the claimed design, while simultaneously finding that those same disclosures in the utility filing anticipated the claimed design.

Background

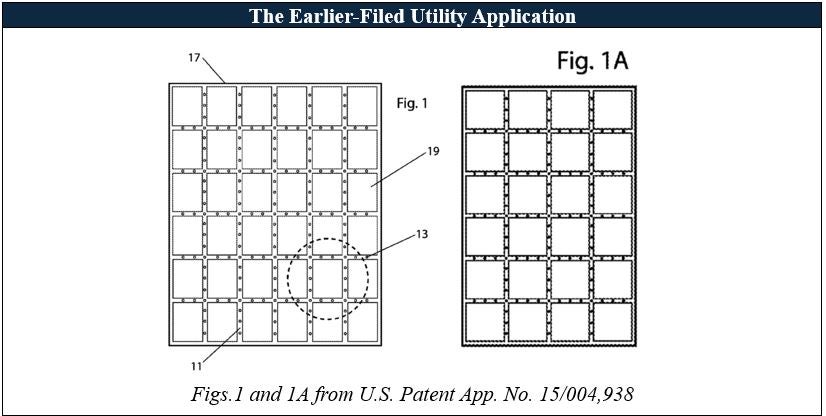

On January 23, 2016, Applicant Bonnie Floyd filed a utility patent application claiming a cooling blanket with ventilated openings along a matrix of sealed compartments. The utility application disclosed figures of cooling blankets in six-by-six and six-by-four arrays.

Three years later, on March 27, 2019, Floyd applied for a design patent claiming the ornamental design of a cooling blanket with rectangular compartments separated by channels of ventilated openings. To secure an earlier filing date, Floyd claimed priority to her previously filed utility application. But unlike the six-by-six and six-by-four arrays depicted in prior utility application, the figures in her design application depicted a six-by-five array of rectangular compartments.

During prosecution of the design application, the Patent Office rejected Floyd’s priority claim to the earlier utility filing because it did not disclose the six-by-five design, and as such, “the claimed design include[d] new matter.” Once priority was denied, the previously-filed utility application became prior art, which the Examiner then relied upon to reject the six-by-five design as being anticipated by the same utility application.

The PTAB agreed with the Examiner’s finding that the utility application did not sufficiently disclose the six-by-five arrangement claimed in the design application. While the utility application contained a generic statement allowing the “embodiment to be made in any size,” the Board interpreted this as referring to the size of the rectangular compartments, not their arrangements. Id. at 4.

The PTAB likewise affirmed the Examiner’s findings that those same disclosures of the utility application anticipated the six-by-five design.

Floyd appealed, challenging both of the Board’s findings.

The Federal Circuit Decision

Recognizing that an earlier utility filing must “reasonably convey” the visual impression of the claimed design, the Federal Circuit found that nothing in Floyd’s utility application would allow a skilled artisan to appreciate the precise six-by-five ornamental arrangement of the later-filed design application. Nor were all intervening arrangements implicitly disclosed because the utility application never articulated a “range of possible arrays rather than the distinct examples depicted in the figures.” Accordingly, Floyd’s design could not claim priority to the earlier-filed utility application.

The Federal Circuit likewise dismissed Floyd’s “inherent” disclosure theory ─ namely, that the utility claims referred to “a plurality of individualized compartments” ─ because nothing in the specification suggested a skilled artisan would necessarily adopt the exact six-by-five arrangement of Floyd’s claimed design. The Federal Circuit instead held that the missing limitation must have necessarily flowed from the earlier utility filing, not merely that it could be selected among many possibilities.

Finally, the Federal Circuit explained that differing legal standards for written description and anticipation allow for a prior utility filing to anticipate a claimed design even though those same disclosures are insufficient to support a priority claim.

Practical Considerations

Prepare Parallel Design and Utility Filings. Where the commercial value of an invention lies in both its function and appearance, applicants should consider filing the design and utility applications in parallel, as opposed to relying on continuation practice. Parallel prosecution eliminates the risk highlighted in Floyd, as each application stands on its own written-descriptions. This dual-track strategy also broadens enforcement options. Whenever possible, applicants should budget for and execute parallel filings at the outset to avoid the evidentiary gaps that may arise when a later-filed design application attempts to retroactively mine aesthetic support from the utility specification.

Prepare Numerous Design Disclosures in the Earlier Utility Filing. If design protection cannot be pursued until after the utility filing, an applicant should consider including numerous design disclosures — drawings, photographs, or other depictions that, even if unnecessary to support the utility claims, unmistakably convey the varying aesthetic features of the product — so that any future design application can rely on the earlier filing as clear written-description support for the claimed design.

Nanjing’s Intellectual Property Protection Center Bans the Use of Generative AI in Drafting Patent Application Documents Submitted for Pre-Examination

On June 4, 2025, Nanjing’s Intellectual Property Protection Center (NIPPC) announced it is banning the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in drafting patent application documents submitted for pre-examination. China’s pre-examination system enables applicants to submit their patent applications to a regional office for an initial examination and potentially receive expedited examination at China’s National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) if certain conditions are met. The NIPPC stated that it was determined that “relevant content [of patent applications] was directly generated by artificial intelligence.”

The NIPPC stated:

I、 Clear prohibition requirements1. It is strictly prohibited to use AI generated content directly in patent application documents. The patent application documents shall be manually written, drawn, edited, and organized by the applicant or their authorized patent agency based on real inventions, research results, and related materials.2. It is strictly prohibited to use AI to generate research and development evidentiary materials, including but not limited to experimental data reports, technical research and development documents, scientific research achievement explanations, etc. The R&D certification materials should be generated by real R&D activities, objectively and accurately reflecting the R&D process and results, and have verifiability and traceability.II、 Explanation of the consequences of violationFor those who violate the prohibition regulations, the relevant pre-trial cases will not be approved, and a “Pre-Examination Quality Notice” will be issued to the applicant and the agency.For serious cases, according to the “Management Measures for Pre Examination Services of Filing Entities and Agency Institutions (2024)” (宁知保〔2024〕32号), the qualification for pre-examination services will be suspended for a certain period of time and included in the negative list of graded and classified management.3. For particularly serious circumstances that clearly violate Article 20 of the Patent Law and Article 11 of the Implementing Regulations of the Patent Law, reports will be made to the administrative authorities at all levels, and corresponding administrative penalties will be recommended for the applicant and the agency in accordance with the law.III、 Notification of verification measuresIn the subsequent pre-examination review of cases, the Nanjing Intellectual Property Protection Center will use various methods to verify the application documents and research and development certification materials, including but not limited to: using professional text detection tools to analyze the originality of the content; organizing review experts to evaluate the rationality, logic, and professionalism of the documents; requiring the applicant to explain, clarify or provide further supporting materials for the key content in the document.

The original Notice is available here (Chinese only).

Failures as a Brand Basis

“What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” – Romeo and Juliet, Act II, Scene II This quote from Shakespeare is prophetic from a trademark standpoint. The primary function of a trademark is to identify and distinguish the goods or services of one party from […]

The post Failures as a Brand Basis appeared first on Attorney at Law Magazine.

Alice Patent Eligibility Analysis Divergence before USPTO and District Court: Federal Circuit Clarifies Limits on Relying on USPTO Findings in § 101 Eligibility Disputes

In our prior article, we discussed instances in which the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) and the district courts made different findings with regard to patent eligibility under 35 U.S.C. § 101. A recent nonprecedential Federal Circuit decision, Aviation Capital Partners, LLC v. SH Advisors, LLC, No. 24-1099 (Fed. Cir. May 6, 2025), highlights a critical procedural point: District courts are not required to accept findings made by the USPTO as true at the pleading stage — unless those findings are specifically alleged in the complaint.

This issue came to the forefront on appeal after the Delaware District Court dismissed Aviation Capital’s patent infringement complaint under Rule 12(b)(6), finding the asserted patent claims ineligible under § 101. The plaintiff-appellant, Aviation Capital Partners (doing business as Specialized Tax Recovery (“STR”)), argued on appeal that the district court erred by failing to accept the USPTO’s prior eligibility analysis, which favored patent eligibility, as a factual finding at the motion to dismiss stage.

Specifically, STR contended that the USPTO’s conclusion — made during prosecution — that the claims were “integrated into a practical application” and “contained significantly more than an abstract idea” should have been accepted as a true factual finding by the District Court as part of deciding the motion to dismiss. But the Federal Circuit rejected that argument outright, stating:

STR additionally argues that, in deciding the motion to dismiss, the district court was required to assume as true the Patent Office’s “factual finding that the claims were integrated into a practical application and contained significantly more than an abstract idea.” Appellant’s Br. 23–25. We disagree. “[F]or the purposes of a motion to dismiss we must take all of the factual allegations in the complaint as true . . . .” Ashcroft v. Iqbal, 556 U.S. 662, 678 (2009) (emphasis added). Here, the complaint included no factual findings made by the Patent Office. J.A. 16–32; Oral Arg. at 4:38–5:45 (complaint alleged the Patent Office made two legal determinations but alleged no factual findings). Accordingly, the district court did not err by declining to accept as true any unalleged factual findings that the Patent Office may have made in its § 101 eligibility analysis.[

This passage underscores the procedural rigor applied to motions to dismiss: The court is bound only to the facts actually pled in the complaint. While STR tried to import the examiner’s analysis into the record, the Federal Circuit made clear that any “factual findings” by the USPTO must be explicitly alleged for a district court to credit them at the motion to dismiss stage.

Implications for Litigants and Drafting Complaints Where Examiner Made Comments Regarding § 101 Eligibility

This ruling serves as a practical guidepost for practitioners navigating § 101 disputes post-Alice. Litigants cannot assume that favorable examiner conclusions — such as an “integration into a practical application” — will be treated as facts unless those determinations are squarely and specifically alleged in the complaint.

The USPTO’s current guidance instructs examiners to evaluate whether a claim is “integrated into a practical application” and whether it includes “significantly more” than an abstract idea — criteria that may allow applications to clear the § 101 hurdle during prosecution. Yet, as Aviation Capital confirms, the deference afforded to such examiner determinations may vary, and on a Rule 12(b)(6) motion, only factual allegations specifically made in the complaint must be taken as true. This begs the question — if a patent owner explicitly alleges factual findings made by an examiner during prosecution regarding § 101, is that sufficient to defeat a motion to dismiss? Though nonprecedential, Aviation Capital suggests as much.

Takeaway

The Aviation Capital decision is a sharp reminder that litigators must be deliberate in pleading factual support for eligibility. To preserve arguments based on examiner findings, those examiner findings must be more than background — they must be alleged facts in the complaint, not just cited conclusions.

Otherwise, courts remain free to assess eligibility from a clean slate. And as this decision reaffirms, that assessment may diverge from what the USPTO previously concluded.

[1] Aviation Capital Partners, LLC v. SH Advisors, LLC, No. 24-1099 at 7 (Fed. Cir. May 6, 2025).

Riding on Empty: ‘Stang’ With No Anthropomorphic Characteristics Isn’t Copyrightable Character

The US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit affirmed a district court’s denial of copyright protection for a car that had a name but no anthropomorphic or protectable characteristics. Carroll Shelby Licensing, Inc. v. Denice Shakarian Halicki et al., Case No. 23-3731 (9th Cir. May 27, 2025) (Nguyen, Mendoza, JJ.; Kernodle Dist. J., sitting by designation).

In 2009, Denice Shakarian Halicki and Carroll Shelby Licensing entered into a settlement agreement resolving a lawsuit concerning Shelby’s alleged infringement of Halicki’s asserted copyright interest in a Ford Mustang known as “Eleanor,” which appeared in a series of films dating back to the 1970s. Under the agreement, Shelby, a custom car shop, was prohibited from producing GT-500E Ford Mustangs incorporating Eleanor’s distinctive hood or headlight design. Shortly thereafter, Shelby licensed Classic Recreations to manufacture “GT-500CR” Mustangs, a move Halicki viewed as a breach of the settlement agreement. Halicki contacted Classic Recreations and demanded it cease and desist in the production of the GT-500CRs.

Shelby filed a lawsuit alleging breach of the settlement agreement and seeking declaratory relief. Halicki counterclaimed for copyright infringement and breach of the agreement. Following a bench trial, the district court ruled in Shelby’s favor on both the breach and infringement claims but declined to grant declaratory relief. Shelby appealed.

The Ninth Circuit began by addressing whether “Eleanor” qualified for copyright protection as a character under the Copyright Act. Although the act does not explicitly list characters among the types of works it protects, the Ninth Circuit has recognized that certain characters may be entitled to such protection. The applicable standard, articulated in 2015 by the Ninth Circuit in DC Comics v. Towle, sets forth a three-pronged test, under which the character must:

Have “physical as well as conceptual qualities”

Be “sufficiently delineated to be recognizable as the same character whenever it appears” with “consistent, identifiable character traits and attributes”

Be “especially distinctive” and have “some unique elements of expression.”

The Ninth Circuit concluded that Eleanor failed to satisfy any of the three prongs of the Towle test. As to the first prong, the Court found that Eleanor functioned merely as a prop and lacked the anthropomorphized qualities or independent agency associated with protectable characters. Regarding the second prong, the Court noted that Eleanor’s appearance varied significantly across the films in terms of model, colors, and condition. Under the third prong, the Court found that Eleanor lacked the distinctiveness necessary to elevate it beyond the level of a generic sports car commonly featured in similar films. Thus, the Court concluded that Eleanor did not qualify as a character, let alone a copyrightable one.

The Ninth Circuit next turned to the parties’ settlement agreement. While California law permits the use of extrinsic evidence to aid in contract interpretation, the Court found the language sufficiently unambiguous to render such evidence unnecessary. Notably, the parties did not include “Eleanor” as a defined term in the agreement, and the term was used in varying contexts throughout the document, conveying different meanings depending on the provision. Ultimately, the Court found a clause that specifically restricted Shelby only from producing vehicles incorporating two design elements associated with Eleanor – its hood and headlight design – to be dispositive. Halicki’s broader interpretation, the Court found, would require an unreasonable reading that pieced together unrelated provisions in a manner unsupported by the agreement’s text.

Finally, the Ninth Circuit addressed the denial of Shelby’s request for declaratory relief. The Court found that the district court erred by conflating Shelby’s breach of contract claim with its separate request for a declaration regarding Halicki’s potential claims. Because Shelby sought clarity as to whether its production of a newer, similar vehicle would infringe Halicki’s asserted rights, the Court held that declaratory relief was warranted. Thus, it remanded the case with instructions for the district court to issue a declaration confirming that Shelby’s conduct did not infringe Halicki’s rights.

No Fair Use Defense Results in Default Judgment

The US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit reversed a district court’s dismissal of a copyright infringement claim alleging copying of a photograph, finding that the defendant’s use of the photograph did not constitute fair use and that the district court erred in its substantive fair use analysis. Jana Romanova v. Amilus Inc., Case No. 23-828 (2d Cir. May 23, 2025) (Jacobs, Leval, Sullivan, JJ.) (Sullivan, J., concurring).

Jana Romanova, a professional photographer, sued Amilus for willful copyright infringement, alleging that the company unlawfully published her photograph, originally licensed to National Geographic, without authorization on its subscription-based website. Amilus failed to appear or respond in the district court proceedings, and Romanova sought entry of default judgment.

Instead of granting the motion, the district court sua sponte raised the affirmative defense of fair use. After considering Romanova’s show cause order response, the district court dismissed the complaint with prejudice, finding that the fair use defense was “clearly established on the face of the complaint.” Romanova appealed on substantive and procedural grounds.

Romanova argued that the district court erred in finding a basis for the fair use defense within the four corners of the complaint and erred by sua sponte raising a substantive, non-jurisdictional affirmative defense on behalf of a defendant that failed to appear or respond.

Citing the Supreme Court decisions in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music (1994) and Warhol v. Goldsmith (2023), the Second Circuit reversed. The Court explained that “the district court’s analysis depended on a misunderstanding of the fair use doctrine and of how the facts of the case relate to the doctrine. We see no basis in the facts alleged in the complaint for a finding of fair use.”

The Second Circuit explained that the district court misapplied the first fair use factor (“the purpose and character of the use”). The Court noted that a transformative use must do more than merely assert a different message; it must communicate a new meaning or purpose through the act of copying itself. Here, Amilus’ use of Romanova’s photograph did not alter or comment on the original work but merely republished it in a commercial context.

The Second Circuit also found no basis for the district court’s finding of justification for the copying, a factor that typically depends on the nature of the message communicated through the copying, such as parody or satire, and was mandated by the Supreme Court in Warhol. The Court rejected the notion that Amilus’ editorial framing – claiming to highlight a trend in pet photography – could justify the unauthorized use.

On the procedural issue, the majority noted that an “overly rigid refusal to consider an affirmative defense sua sponte can make a lawsuit an instrument of abuse. A defendant’s default does not necessarily mean that the defendant has insouciantly snubbed the legal process.” In this case, the Second Circuit explained that it “cannot fault the district court for considering a defense which it believed (albeit mistakenly) was valid and important. While district courts should indeed be cautious before sua sponte invoking affirmative defenses on behalf of defaulting defendants, they should also be cautious about not considering such defenses.”

In his concurrence, Judge Sullivan disagreed on the procedural issue. He took the position that the district court’s sua sponte invocation of an unasserted affirmative defense was itself reversible error. Since fair use is an affirmative defense, Judge Sullivan noted that the party asserting the defense bears the burden of proof. He warned that judicial overreach via sua sponte assertions could undermine the adversarial process, particularly in default settings.

Practice Note: The ruling underscores the Second Circuit’s continued alignment with the Supreme Court’s narrowing of the fair use doctrine in Andy Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith, particularly with respect to commercial uses that do not involve commentary, criticism, or other transformative purposes. The Court’s opinion includes a comprehensive survey of fair use jurisprudence, making it a valuable reference for copyright practitioners.

X-Ray Vision: Court Sees Through Implicit Claim Construction

The US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit reversed the Patent Trial & Appeal Board’s final determination that challenged patent claims were not unpatentable, finding that the Board’s decision relied on an erroneous implicit claim construction. Sigray, Inc. v. Carl Zeiss X-Ray Microscopy, Inc., Case No. 23-2211 (Fed. Cir. May 23, 2025) (Dyk, Prost, JJ.; Goldberg, Chief Distr. J., sitting by designation).

Zeiss owns a patent related to X-ray imaging systems that incorporate projection magnification. Sigray filed a petition requesting inter partes review (IPR) of all claims in the patent. After institution, the Board issued its final written decision, which declined to hold any of the challenged claims unpatentable. Sigray appealed.

On appeal, Sigray argued that the claims were unpatentable based on a single prior art reference, Jorgensen. The Jorgensen reference “describes a system that uses an X-ray source to generate an X-ray beam, which then passes through a sample before being received by a detector.” Sigray argued that Jorgensen anticipated or rendered the challenged claims obvious. The parties agreed that Jorgensen explicitly disclosed all the limitations of the independent claim except for one reading “a magnification of the projection X ray stage . . . between 1 and 10 times.”

The parties’ arguments centered on whether the magnification limitation was inherently disclosed in Jorgensen. The Board concluded that “viewing the record as a whole, . . . [Sigray] has not shown persuasively that Jorgensen inherently discloses projection magnification within the claimed range. Sigray argued, and the Federal Circuit agreed, that the Board’s findings incorrectly relied on a flawed understanding of the claimed range. In Sigray’s view, “the Board implicitly and incorrectly construed the limitation ‘between 1 and 10’ to exclude unspecified, small divergence resulting in projection magnifications only slightly greater than 1.” This was illustrated by the Board’s determination that Sigray “failed to show that the . . . X-ray beam in Jorgensen diverges enough to result in projection magnification between 1 and 10 times.”

The Federal Circuit found that the Board’s use of the term “enough” indicated that the evidence it relied on supported a finding of some divergence in the X-ray beams. Because the beams were not completely parallel, the Court reasoned that some magnification necessarily resulted, and that even a miniscule amount (as disclosed in the prior art) fell within the claimed magnification range of 1 to 10. Since the Board made only one evidence-supported finding relevant to anticipation, the Court reversed on the independent claim and two dependent claims without remand. However, the Court remanded the case to the Board to determine whether the three remaining challenged claims, which recited further material limitations, would have been obvious.

Eminem Sues Meta for $109M Over Unauthorized Music Use

Eminem Sues Meta for $109M Over Unauthorized Music Use. The rap icon’s team says Meta used his music without permission hundreds of times. Now they want justice. His music publishing company, Eight Mile Style, has filed a major lawsuit against Meta, the parent company behind Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp. The core of the complaint? They […]

FTC Revives Orange Book Listing Challenges

On May 21, 2025, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) issued its third round of warning letters – and its first under the Trump administration – against pharmaceutical manufacturers for allegedly improper listing of patents in the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Orange Book. The FTC made clear that its prerogative under President Trump’s leadership is to seek “transparent, competitive, and fair healthcare markets.”

The FTC issued renewed warning letters to drugmakers that did not delist previously challenged Orange Book listings, disputing more than 200 patents across 17 brand-name pharmaceuticals. The patents relate to device components of combination drug-device products treating asthma, diabetes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The FTC alleges the device patents constitute improper listings that allow brand-name manufacturers to delay – or even prohibit – generic competition. These patents were previously the subject of warning letters the FTC issued in November 2023 and April 2024 to more than a dozen pharmaceutical manufacturers. Although some manufacturers delisted patents in response to the initial warning letters, others chose to continue listing the targeted patents in the Orange Book.

In Depth

BACKGROUND

The FTC issued a policy statement in 2023 under Chair Lina Khan declaring that “improper” pharmaceutical patent listings in the Orange Book may constitute an unfair method of competition in violation of Section 5 of the FTC Act. The patents are listed for the purpose of putting generic rivals on notice to deter patent infringement. The FDA, however, takes only a ministerial role as to listing patents and does not assess whether patents are properly listed in the Orange Book. Following the 2023 policy statement, the FTC issued a series of warning letters to manufacturers.

In the FTC’s recent warning letters, the agency cites the December 2024 US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit decision in Teva Branded Pharm. Prods. R&D, Inc. v. Amneal Pharms. of N.Y., LLC as support for their assertion that the previously identified patents are improperly listed. The Federal Circuit affirmed a lower court’s order requiring Teva to delist five patents associated with its ProAir® HFA inhaler, a drug-device combination product, from the Orange Book. The court found Teva had improperly listed its ProAir HFA inhaler patents in the Orange Book for primarily two reasons:

First, Teva had misinterpreted the requirements set forth in the listing statute by arguing that the term “drug” encompasses any component of an article that treats a disease, and therefore its patents claiming the device components would also “claim the drug.” The Federal Circuit rejected this argument, holding that determining whether a patent is properly listed “requires what amounts to a finding of patent infringement,” and the mere fact that a product could infringe a patent does not mean the patent “claims” the underlying drug.

Second, Teva argued that a patent can be listed when it claims any part of the product other than the active ingredient, and therefore its patents that claim the device component are valid. The Federal Circuit rejected this argument, holding that in order for a patent to claim the “drug” and be listed in the Orange Book, the patent must claim at least the active ingredient of the approved product, as the active ingredient provides the primary mode of action of the drug.

The Federal Circuit subsequently denied Teva’s request for an en banc rehearing in March 2025. Notwithstanding Teva’s petition seeking Supreme Court review, Teva must now delist the five patents.

WHAT’S NEXT

On the day following the Federal Circuit’s opinion, the FTC issued a press release applauding the Federal Circuit’s holding and reiterating its position that, due to the 30-month statutory stay triggered by listing patents in the Orange Book, improper listings can negatively affect competitive conditions permitting generic entry of competing drug products. The press release, however, was issued in the waning days of Chair Khan’s tenure with a Democratic majority at the FTC, and practitioners and industry stakeholders alike questioned whether the FTC’s policy on Orange Book listings would continue under a Republican-led FTC. The recent warning letters suggest that, under current Chair Andrew Ferguson, the FTC appears to be sticking to the prior administration’s policy and remains focused on enhancing competition between brand-name and generic pharmaceuticals to lower healthcare costs.

The Federal Circuit’s decision vindicated the FTC’s position against improper listings in the Orange Book and likely empowered the agency to undertake the most recent enforcement efforts despite the change in administration. The agency’s continued scrutiny of patent listings in the Orange Book indicates it is possible the FTC may pursue enforcement actions concerning its Orange Book challenges in the future. Therefore, brand-name manufacturers are advised to carefully review their current listings, paying particular attention to the underlying claim of the patent, as patents that do not claim the active ingredient in the drug may be considered improperly listed. Brand-name manufacturers are encouraged to proactively seek counsel when conducting such reviews to ensure compliance.

Mondelēz Sues Aldi Over Alleged Copycat Packaging in U.S. Federal Court

Mondelēz Sues Aldi Over Alleged Copycat Packaging in U.S. Federal Court. Mondelēz International (commonly referred to as Mondelez International), maker of Oreo, Nutter Butter, and Chips Ahoy! has filed a federal lawsuit against grocery retailer Aldi. The complaint, filed on May 27, 2025, in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois, accuses […]

$222M Jury Verdict Against Walmart in Trade Secret Case Reflects Growing Trend

Monetary awards in trade secrets cases continue to grab headlines in 2025. A reported in this recent blog post, a Boston jury awarded a medical device company $452M for theft of trade secrets by a competitor, later reduced to $59.4 in exchange for a permanent injunction. Last month, an Arkansas jury found Walmart liable for trade secret misappropriation and awarded $222M to the plaintiff, Zest Labs, a provider of technology solutions for tracking food freshness. And then there is the $2.036 billion jury award in favor of Appian Software against Pegasystems that was vacated by the Virginia Court of Appeals in 2024 but was granted review by the Virginia Supreme Court just a few months ago. These awards are part of a growing trend of very large monetary awards in trade secrets cases.

Getting trade secrets cases to trial and winning on the merits is arguably easier than in patent cases. One of the main reasons for this belief is that patent infringement cases involve case-dispositive legal issues that courts decide pre-trial: the meaning and scope of the claims and whether claims are sufficiently definite. Many patent cases never get past this Markman stage. While courts in trade secrets cases often must decide whether the asserted trade secret is sufficiently identified to present to a jury, the plaintiff is frequently given several opportunities to fix its articulation of the secret before trial. By contrast, patent claims cannot be fixed during litigation. Moreover, given their fact intensive character, trade secrets cases often have an easier road to trial than patent cases, and strong narratives often emerge from these cases that involve related claims for breach of contractual secrecy obligations and civil conspiracy. A Stout 2024 report pegs trial win rates for plaintiffs bringing trade secret claims in federal court at 84% since 2017, with juries awarding some form of monetary damages in 78% of the cases.

Monetary and non-monetary remedies available for trade secret misappropriation, in both state and federal courts, are robust and relatively easy to access in comparison to patent cases. Patent jurisprudence on remedies often throttles damages recovery in ways that trade secrets law does not, and injunctive relief against post-trial infringement is significantly constrained because courts often regard harm as compensable by the availability of an ongoing royalty. Unlike in utility patent cases, disgorgement of ill-gotten gains is available in trade secret cases and often these alleged gains far exceed any provable economic loss. As with patent cases, proving damages in trade secrets cases depends heavily on expert testimony, but the controlling law in patent cases is far more developed and restrictive than in the trade secrets context when it comes to screening expert damages theories.

Similarly, although both patent and trade secrets law reserve an award of attorneys’ fees to the trial court’s discretion in exceptional cases, the practical threshold for such awards may be lower for successful plaintiffs in trade secrets cases. Last month, a federal court in California awarded attorneys’ fees to the plaintiff who proved misappropriation of only one of twenty-eight asserted trade secrets and only recovered 1.1% of the damages it originally sought. In granting the fees motion, the court held that winning “any significant issue … which achieves some benefit in bringing suit” is sufficient to justify a full recovery of attorneys’ fees.

Trade secret owners’ run of success in courtrooms across the country seems likely to continue. These cases are more likely to go to trial because of their fact-specific nature, and the enhanced remedies available to trade secret holders often justifies rolling the dice. This trend behooves those potentially facing trade secret misappropriation risk to carefully manage that risk through contracts with trade secret owners and to thoughtfully and proactively defend claims asserted against them while realistically evaluating the litigation risk they face.