$222M Jury Verdict Against Walmart in Trade Secret Case Reflects Growing Trend

Monetary awards in trade secrets cases continue to grab headlines in 2025. A reported in this recent blog post, a Boston jury awarded a medical device company $452M for theft of trade secrets by a competitor, later reduced to $59.4 in exchange for a permanent injunction. Last month, an Arkansas jury found Walmart liable for trade secret misappropriation and awarded $222M to the plaintiff, Zest Labs, a provider of technology solutions for tracking food freshness. And then there is the $2.036 billion jury award in favor of Appian Software against Pegasystems that was vacated by the Virginia Court of Appeals in 2024 but was granted review by the Virginia Supreme Court just a few months ago. These awards are part of a growing trend of very large monetary awards in trade secrets cases.

Getting trade secrets cases to trial and winning on the merits is arguably easier than in patent cases. One of the main reasons for this belief is that patent infringement cases involve case-dispositive legal issues that courts decide pre-trial: the meaning and scope of the claims and whether claims are sufficiently definite. Many patent cases never get past this Markman stage. While courts in trade secrets cases often must decide whether the asserted trade secret is sufficiently identified to present to a jury, the plaintiff is frequently given several opportunities to fix its articulation of the secret before trial. By contrast, patent claims cannot be fixed during litigation. Moreover, given their fact intensive character, trade secrets cases often have an easier road to trial than patent cases, and strong narratives often emerge from these cases that involve related claims for breach of contractual secrecy obligations and civil conspiracy. A Stout 2024 report pegs trial win rates for plaintiffs bringing trade secret claims in federal court at 84% since 2017, with juries awarding some form of monetary damages in 78% of the cases.

Monetary and non-monetary remedies available for trade secret misappropriation, in both state and federal courts, are robust and relatively easy to access in comparison to patent cases. Patent jurisprudence on remedies often throttles damages recovery in ways that trade secrets law does not, and injunctive relief against post-trial infringement is significantly constrained because courts often regard harm as compensable by the availability of an ongoing royalty. Unlike in utility patent cases, disgorgement of ill-gotten gains is available in trade secret cases and often these alleged gains far exceed any provable economic loss. As with patent cases, proving damages in trade secrets cases depends heavily on expert testimony, but the controlling law in patent cases is far more developed and restrictive than in the trade secrets context when it comes to screening expert damages theories.

Similarly, although both patent and trade secrets law reserve an award of attorneys’ fees to the trial court’s discretion in exceptional cases, the practical threshold for such awards may be lower for successful plaintiffs in trade secrets cases. Last month, a federal court in California awarded attorneys’ fees to the plaintiff who proved misappropriation of only one of twenty-eight asserted trade secrets and only recovered 1.1% of the damages it originally sought. In granting the fees motion, the court held that winning “any significant issue … which achieves some benefit in bringing suit” is sufficient to justify a full recovery of attorneys’ fees.

Trade secret owners’ run of success in courtrooms across the country seems likely to continue. These cases are more likely to go to trial because of their fact-specific nature, and the enhanced remedies available to trade secret holders often justifies rolling the dice. This trend behooves those potentially facing trade secret misappropriation risk to carefully manage that risk through contracts with trade secret owners and to thoughtfully and proactively defend claims asserted against them while realistically evaluating the litigation risk they face.

Federal Circuit Sinks Appeal Over Design Patent Claiming Well-Known Pool Features

The US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit recently affirmed a summary judgment of no design patent infringement in North Star Tech. Int’l Ltd. v. Latham Pool Products, Inc., ruling that the patented and accused pool designs were “plainly dissimilar” despite sharing structural similarities formed by geometric shapes and angular edges common in preexisting pool designs.

Background

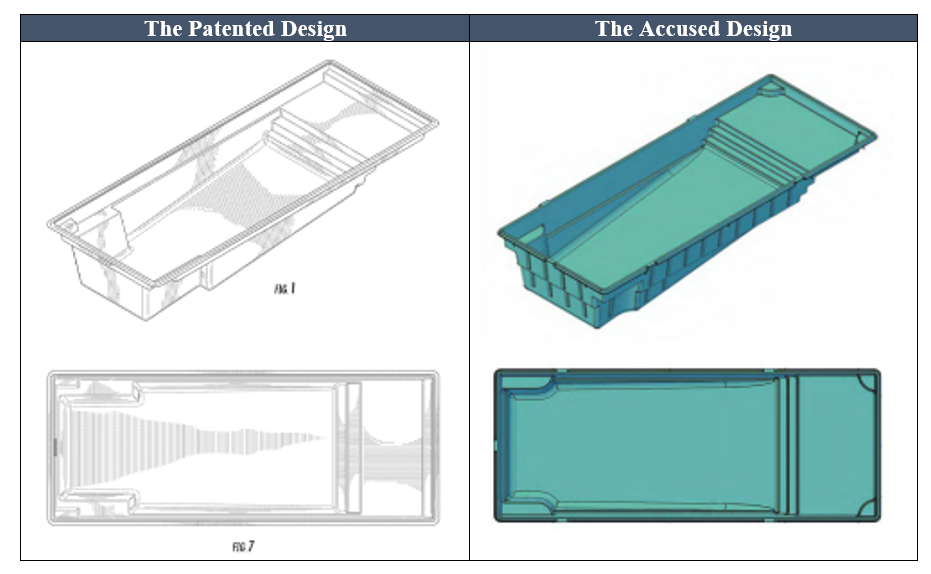

In April 2019, North Star filed a complaint against Latham in the Eastern District of Tennessee alleging infringement of US Design Patent No. D791,966 (D’966), which claims the ornamental appearance of a fiberglass swimming pool. As shown below, both the patented North Star design and accused Latham design relate to rectangular pools with tanning ledges and built-in benches.

Latham moved for summary judgment of non-infringement, arguing that the designs are plainly dissimilar and that “any similarities that do exist between the D’966 Patent and the [accused] designs stem from their use of design elements that were commonly used in pool designs before the D’966 Patent.” Put differently, the accused design could not infringe the D’966 Patent because it did not incorporate any claimed design elements other than those in the prior art.

The district court agreed, explaining that the “prominent ornamental elements of the two designs” — viz., the shape of the entry steps and deep end benches — “differ significantly, creating an overall ‘plainly dissimilar’ appearance.” A review of the prior art further confirmed non-infringement because “[e]ach of the pertinent design elements included in the D’966 Patent and [the accused design] existed before North Star filed the D’966 Patent.” To be sure, the district court cited to examples of fiberglass pools with rectangular tanning ledges that pre-date the patented design, as well as to Latham’s own use of the same deep end benches in prior art pool designs. The district court therefore entered final judgment dismissing the design patent infringement claim, which North Star subsequently appealed.

Federal Circuit Decision

On appeal, the Federal Circuit affirmed the grant of summary judgement after concluding that the patented and accused designs were “plainly dissimilar” for two reasons.

First, applying the Egyptian Goddess test, the Federal Circuit held that the overall appearance of the patent and accused pool designs differed significantly to an ordinary observer, which is a “homeowner considering purchasing a swimming pool in their home.” Like the district court, the Federal Circuit found that the ornamental features of the patented design are characterized by “straight edges and geometric shapes” that collectively produce an “overall angular appearance,” while those of the accused design are characterized by “rounded shapes” and a “curved” design.

For example, the entry step is a pool-width rectangle in the patented design but two separate quarter circles in the accused design, as shown in the comparison chart below.

Second, the Federal Circuit disregarded the structural similarities between the patented and accused design because “North Star cannot monopolize common ornamental pool features or functional pool features by registering a combination of those features as a design patent.” So even though both designs relate to rectangular swimming pools with steps, benches, and tanning ledges, the Federal Circuit ruled that “North Star’s patent only protects the ornamental aspects ─ here, the angular shape ─ of those ubiquitous features.”

Looking Ahead

While nonprecedential, the North Star decision provides a roadmap for litigants to escape design patent infringement claims that cover common or well-known features. Patent applicants would do well to focus on the distinctive ornamental elements of their designs and avoid overreliance on combinations of preexisting design features.

Undetectable Amount of Magnification IS Magnification

This Federal Circuit Opinion[1] analyzes invalidity based on anticipation and obviousness, more specifically based on implicit claim construction of the claim limitation and inherent disclosures.

Background

Sigray, Inc. (“Sigray”) filed an Inter Partes Review (“IPR”) petition challenging claims 1–15 of Zeiss X-Ray Microscopy, Inc.’s (“Zeiss”) U.S. Patent No. 7,400,704 (the “‘704 Patent”) as invalid for anticipation and obviousness over various references. For claims 1, 3, and 4, Sigray alleged that S. Jorgensen et al., Three-Dimensional Imaging of Vasculature and Parenchyma in Intact Rodent Organs with X-ray Micro-CT, Am. J. Physiology (Sept. 1998) (“Jorgensen”), which describes using an X-ray beam to image rodent organs, anticipated these claims. Sigray further argued that claims 2, 5, and 6 were rendered obvious, in part, by Jorgensen.

The ‘704 Patent claims X-ray optics requiring that “magnification of the projection x-ray stage is between 1 and 10 times”—the only limitation in independent claim 1 not agreed to be disclosed in Jorgensen by both parties. Notably, neither party requested formal claim construction, and the USPTO stated it did not engage in claim construction. Instead, the USPTO analyzed the claim language based on the following facts regarding Jorgensen:

Jorgensen describes a process called collimation, which, according to U.S. Patent No. 4,891,829, is used to “achieve [the required] degree of parallelism.” The USPTO found this confirms that collimation is a technique for “minimizing beam divergence” and producing “a nearly parallel” X-ray beam. Zeiss’s expert, Dr. Gonzalo Acre, testified that a “collimated X-ray beam is a beam where . . . no meaningful divergence is present,” and that “the X-rays that reach Jorgensen’s sample are essentially parallel (i.e., not diverging), and there is no projection stage magnification.”

Jorgensen’s prefatory clause references an “X-ray focal spot that subtends ≤0.8 mrad at the [detector],” which Zeiss’s expert, Dr. Julie Bentley, testified is “a very small angle and small enough to be considered [a] parallel source at infinity.”

Dr. Bentley further testified that Jorgensen explains that when magnification of the lens is set to 2x, the sample size doubles (a 12 μm square at the sample corresponds to a 24 μm square at the detector). This can only occur “only if” there is no additional magnification at the projection stage; if the projection stage magnification were even 1.1x, a 24 μm detector pixel would correspond to only a 10.9 μm sample pixel, not 12 μm, as Jorgensen states.

Jorgensen explains that “[t]he geometry and intensity distribution of the X-ray focal spot are of concern if the X-ray beam geometry is used to achieve magnification, but in our system the long X-ray focal spot-to-[sample] distance and the close proximity of the [sample] to the [detector] greatly reduce this concern.”

Based on these facts, the USPTO concluded that Sigray “fail[ed] to show that the . . . X-ray beam in Jorgensen diverges enough to result in projection magnification ‘between 1 and 10 times’. . . ” The USPTO, therefore, found that Jorgensen does not teach X-ray optics with projection stage magnification in the claimed range.

Issue(s)

Did the USPTO engage in claim construction even though the parties did not request it and the USPTO stated it did not perform claim construction?

Is the USPTO’s finding—that the claims are not unpatentable because Jorgensen’s small amount of magnification does not describe a projection magnification “between 1 and 10 times”—a reversible error in claim construction?

Holding(s)

Yes, the USPTO engaged in claim construction.

Yes, the USPTO’s claim construction finding that the claims are not unpatentable is an error that can be reversed by the Federal Circuit because the facts support the opposite—that the disputed claim limitation is anticipated.

Reasoning

USPTO Engaged in Claim Construction by Implicitly Construing the Claim

The Federal Circuit held that the USPTO’s use of the word “enough” reflects that the USPTO considered a certain level of divergence as outside the claim, and that this narrowing of claim scope constitutes claim construction. Because the Federal Circuit was reviewing a claim construction opinion—which is ultimately a question of law—it could review the decision de novo.

USPTO’s Conclusion that the Claims are Not Unpatentable is a Reversible Error

The Federal Circuit disagreed with the USPTO’s conclusion that the “between 1 and 10” magnification requirement in the claim language excludes small amounts of magnification. The Federal Circuit relied on SmithKline Beecham Corp. v. Apotex Corp., which held that the district court erred in requiring a higher standard of proof because it was “sufficient to show that the natural result flowing from the operation as taught [in the prior art] would result in” the claimed invention. 403 F.3d 1331, 1343 (Fed. Cir. 2005).

In addressing point (a), the Federal Circuit held that phrases such as “minimizing beam divergence,” “nearly parallel X-ray beam,” “no meaningful divergence,” and “essentially parallel” X-rays all indicate that there is some resultant, and possibly undetectable, magnification, which falls “between 1 and 10” projection magnification.

Similarly, in response to points (b) and (d), even though the X-ray focal spot is “small enough to be considered [a] parallel source at infinity,” and the design in Jorgensen “greatly reduces” any concern for magnification, these terms do not eliminate the possibility of projection magnification.

Finally, in response to point (c), the Federal Circuit applied a 1.001x magnification and the same rounding principles as Dr. Bentley to arrive at 12 μm, indicating that a minor magnification can result in an undiscernible size difference and contradicting Dr. Bentley’s testimony that the 12 μm size can be obtained “only if” there is no magnification.

Relying on Owens Corning v. Fast Felt Corp., the Federal Circuit reversed the USPTO’s finding that claim 1 is not unpatentable, concluding it is unpatentable because “on the evidence and arguments presented to the Board, there is only one possible evidence-supported finding: [that] the Board’s [determination] . . . when the correct construction is employed, is not supported by substantial evidence.” 873 F.3d 896, 901-02 (Fed. Cir. 2017).

Because no distinction was argued for dependent claims 3 and 4, the Federal Circuit found these claims also unpatentable. For claims 2, 5, and 6, which were not asserted as anticipated by Jorgensen, the Federal Circuit remanded to the USPTO to consider whether these claims would have been obvious.

FOOTNOTES

[1] Sigray, Inc. v. Carl Zeiss X-Ray Microscopy, Inc. No. 2023-2211

Listen to this article

Beijing IP Court Releases 2024 Annual Cases

On April 30, 2025, the Beijing IP Court (BIPC) released their list of 2024 annual cases including 7 IP-related cases and 1 antitrust case. The Court explained that the cases “cover the four major intellectual property trial areas of patents, trademarks, copyrights, and competition and monopoly, involving innovative achievements in emerging industries in key areas such as medicine, communications, seed industry, platform economy and data. These cases reflect five major characteristics: increasing efforts to protect industrial innovation in key areas, cracking down on intellectual property infringements, helping to build a high-level socialist market economic system, serving the development of the intellectual property rule of law, and contributing Chinese wisdom to world intellectual property governance.”

Press conference releasing the 2024 annual cases.

The original text is available here via social media as the BIPC seems to be geoblocked as of the time of writing.

As summarized by the BIPC:

Case Ⅰ: Standard-Essential Patent Infringement and Royalty Rate Dispute——Assisting a Renowned Enterprise in the Communications Field to Reach a Global Settlement1. Case InformationPlaintiff: X CompanyDefendant: X Guangdong Mobile Communications Company.2. Basic FactsBoth parties to this case are renowned enterprises in the field of communications. At the time of this trial, the two parties had been engaged in licensing negotiations for many years over the 3G and 4G standard – essential patent portfolios, and there were numerous related parallel litigations in various jurisdictions globally, including infringement claims and tariff claims. The plaintiff is the holder of the invention patent titled ‘Base Station Device, Mobile Station Device and Communication Method’. It claims that the patent involved is a standard – essential patent of the LTE communication standard, and believes that the defendant’s acts of manufacturing, selling and offering for sale the two models of mobile phones involved constitute an infringement of the patent right involved, and requests the court to order the defendant to stop the infringing acts.The plaintiff did not file a claim for damages and stated that the purpose of its lawsuit was to advance the licensing negotiations. The defendant filed a counterclaim in the dispute over the royalties of the standard essential patents in this case, requesting the court to make a judgment on the licensing conditions, including but not limited to the licensing royalties, within the scope of mainland China for the 3G and 4G standard essential patents which the plaintiff owns and has the right to license for the intelligent terminal products manufactured and sold by the defendant. After trial, the Beijing Intellectual Property Court held that the counterclaim filed by the defendant met the acceptance conditions, thereby accepted the defendant’s counterclaim and actively promoted the joint trial of the two lawsuits, and finally facilitated the two parties to successfully reach a global patent cross – licensing agreement. On the same day, the parties applied for the withdrawal of this case and the counterclaim respectively on the grounds of reaching a settlement, and the Beijing Intellectual Property Court ruled to approve the withdrawal of the lawsuit by both parties.3. Judgment GistWhen a standard-essential patent holder files a patent infringement lawsuit, requesting the court to order the implementer to stop infringing the patent involved, and the implementer files a counterclaim, requesting the court to rule on the licensing conditions of the standard – essential patent portfolio including the patent involved, the court may take into account the fact that both the counterclaim and the original claim need to examine the same fact, that is, the licensing negotiation matters between the patent holder and the implementer regarding the patent involved and the related standard – essential patent portfolio.The counterclaim should be accepted and jointly tried, in a situation where there is a high degree of correlation between the counterclaim and the original claim.4.Typical SignificanceUnder civil procedure law theory, the relationship between the counterclaim and the original claim serves as the basis for their joint trial. The closer the substantive legal relationship between the original claim and the counterclaim, the more necessary it is to jointly try them in the same case. Article 233 of the “Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court Concerning the Application of the Civil Procedure Law of the People’s Republic of China (Amended in 2022)” (referred to as the Judicial Interpretation Concerning the Civil Procedure Law) stipulates the acceptance conditions for counterclaims, stating that if the counterclaim and the original claim are based on the same legal relationship, there is a causal relationship between the claims, or the counterclaim and the original claim are based on the same fact, the people’s court should jointly try them. Generally, the counterclaims and original claims accepted by the people’s court are based on the same legal relationship or the same fact, but there are certain particularities in the field of standard – essential patents.A patent that must be used to implement a certain technical standard is called a standard-essential patent. With the vigorous development of the digital economy, standard-essential patent technologies are widely applied in fields such as mobile communication, intelligent connected vehicles, and the Internet of Things. A smart terminal product often contains thousands of standard – essential patents. Against the backdrop of intensified market competition and accelerated technological iteration, licensing negotiations and disputes surrounding standard-essential patents are increasing day by day. In a standard-essential patent infringement case, the right basis usually only involves one or several patents, and the alleged infringing product is also specific. However, in actual licensing negotiations, the two parties often conduct negotiations concerning the entire standard – essential patent portfolio of the patent holder and all related products of the implementer. This leads to a situation where a standard – essential patent infringement lawsuit and a royalty rate lawsuit are not consistent in the scope of patents and products involved. So, on the surface, it does not meet the general acceptance conditions for counterclaims in the civil procedure law. This is exactly the case in this lawsuit. Based on this, the Company claimed that the counterclaim filed by the Mobile Communications Company should not be accepted, and further claimed that the original claim and the counterclaim did not involve the same fact because it did not request the calculation and payment of infringement damages based on the licensing fees in this case.In response to this claim, the court referred to the previous judicial practice of standard – essential patent trials, comprehensively considered the trial ideas and judgment logic of standard – essential patent infringement lawsuits and royalty rate lawsuits, and held that in an infringement lawsuit involving standard-essential patents, whether to order the defendant to stop the infringement is not only determined by whether the defendant has implemented the patent involved without permission, but also by whether the negotiating parties have violated the FRAND obligation. To determine whether the patent holder has violated the FRAND licensing obligation and whether the implementer has violated the obligation of good faith negotiation, in addition to examining the negotiating behaviors of both parties, it is also necessary to examine whether the licensing conditions proposed by both parties during the negotiation process are obviously unreasonable. These licensing conditions are not only for the patent involved, but for all 3G and 4G standard-essential patents for which the X Company has the right to grant licenses. To determine whether the licensing conditions proposed by both parties are obviously unreasonable, it is necessary to determine the reasonable range of licensing conditions, and the trial content of the royalty rate lawsuit for standard-essential patents is exactly the licensing conditions.Based on this special trial logic, although the counterclaim and the original claim in this case are not based on the same legal relationship, there is a causal connection between them, and both are closely related to the fact of the licensing negotiation between the two parties. On this basis, the Beijing Intellectual Property Court held that the the counterclaim should be accepted and jointly tried.The acceptance of the counterclaim aligns with the interests of the parties, which was mutually acknowledged by both sides. The essence of standard -essential patent disputes is to promote negotiation consensus through litigation confrontation, and seek negotiation benefits through litigation procedures. In this case, on the one hand, the patent holder has already initiated an infringement lawsuit and sought injunctive relief in advance, on the other hand, the patent implementer hopes that the court will rule on the licensing conditions. If the counterclaim of the patent implementer is not accepted, it can only initiate another subsequent lawsuit, and a new lawsuit may still need to go through complex and time-consuming procedures such as service of process in foreign-related cases and objections to jurisdiction. This is not only inefficient, but also the sequence and speed of the two lawsuits may affect the negotiating positions of the two parties. Facts have proved that the joint trial of the two lawsuits promoted the two parties to successfully reach a global cross-licensing agreement and subsequent cooperation plan, which resolved the long-standing patent disputes between the two parties and achieved a win-win cooperation between the two parties.This case not only delves deep into the application of the law and clarifies the conditions for the joint trial of a standard-essential patent infringement lawsuit and a counterclaim for standard-essential patent royalties, but also adheres to the judicial concept of “promoting negotiation through trial and substantially resolving disputes”, promoting the substantial resolution of disputes, maximizing the interests of both parties, and promoting industrial licensing. The fair and efficient trial of this case demonstrates the high level and professionalism of China’s judicial protection of intellectual property rights, and reflects the wisdom and responsibility of Chinese courts in the new era in resolving international disputes, as a useful reference for the trial of similar cases in the future.

Case Ⅱ: Administrative Litigation Case Regarding the Invalidation of the Patent Right for “A Crystalline Form of Rocuronium Bromide”—— Assessing the Inventiveness of a Pharmaceutical crystalline form Patent Based on Technical Effects1. Case InformationPlaintiff: Chengdu Xin X pharmaceutical companyDefendant: National Intellectual Property AdministrationThird Party: Wang XX2. Basic FactsThe plaintiff is the patentee of an invention patent titled “A Crystalline Form of Rocuronium Bromide”. The third party filed a request with the National Intellectual Property Administration to declare the patent invalid. The National Intellectual Property Administration issued a decision under appeal declaring the entire patent invalid. Then the patentee filed an administrative lawsuit with the Beijing Intellectual Property Court, claiming that this patent achieved unexpected technical effects and had been commercialized and marketed with actual industrial value, and that the Claim 1 of this patent is inventive and the decision under appeal is incorrect. After the trial, the Beijing Intellectual Property Court held that crystalline form A of rocuronium bromide in this patent had better technical effects compared to the rocuronium bromide solid disclosed in the prior art, and that this patent is inventive and the decision under appeal was incorrect in this regard. Accordingly the court ruled to revoke the decision under appeal and ordered the National Intellectual Property Administration to make a new examination decision. After the judgment was pronounced, none of the parties appealed, and the first-instance judgment of this case has taken effect.3. Judgment GistWhen assessing the inventiveness of a pharmaceutical crystalline form patent, even if obtaining the crystalline form itself is obvious, it doesn’t necessarily mean it lacks inventiveness. It’s still necessary to consider its technical effects compared to the prior art. If the crystalline form achieves better technical effects than the prior art, and these effects are closely related to the formation of the medicine, it can be determined that the crystalline form patent is inventive.4. Typical SignificanceThe pharmaceutical and healthcare industry is not only a core component of China’s strategic emerging industries but also an important area related to people’s livelihood and well-being. Its sustainable development has a profound impact on the overall economic and social situation. As a typical technology – intensive industry, the pharmaceutical field is characterized by high investment in research and development, long cycles, and high risks. Therefore, intellectual property protection plays a prominent role in stimulating technological innovation, improving drug accessibility, and promoting industrial upgrading.Pharmaceutical patents are the most core intellectual property achievements of pharmaceutical enterprises. Regarding a certain drug, the patents obtained by pharmaceutical enterprises for different technical solutions form a complete patent system, including the effective active compound as well as the corresponding crystalline form and the composition. This system is like a “firewall” or a “moat”, and it effectively ensures that pharmaceutical enterprises can fully realize the commercial interests of the drug during the patent exclusivity period, enhancing their market competitiveness. The crystalline form patent in question in this case is a common type of pharmaceutical patent. The crystalline form usually refers to the solid existence form of the drug’s active compound. Due to different crystallization conditions and processes, the active compound of the same drug may yield crystalline forms with different spatial structures and molecular arrangements. This phenomenon of polymorphism in drugs is very important for drug research and development, because different crystalline forms exhibit different physical and chemical properties. This not only affects the preparation, processing, and storage of the drug, but also affects the dissolution and release characteristics of the drug in the human body, thus affecting the efficacy and safety of the drug. On the one hand, the selection of the crystalline form is of great significance for drugs. On the other hand, enterprises have invested a large amount of manpower and financial resources in the research and development of crystalline forms. Therefore, original research pharmaceutical companies usually include the crystalline form, compound, composition, and other inventions in the scope of patent applications together to form a multi-level and all-round pharmaceutical patent protection system.Generic pharmaceutical companies will also increase their efforts in researching the crystalline forms of known active compounds of drugs, and strive to avoid the crystalline form patents of original research pharmaceutical companies, in order to compete in the market for this drug. It can be seen how important crystalline form patents are for pharmaceutical enterprises and the pharmaceutical industry.As the exclusive jurisdiction court for administrative cases regarding patent authorization and confirmation across the country, the Beijing Intellectual Property Court has always attached great importance to the trial of administrative cases of requests for invalidation of patents related to pharmaceutical crystalline forms. By applying the rules of inventiveness judgement correctly, the judgment of this case clarifies the factors to be considered for the technical effects of pharmaceutical crystalline form patents, providing a reference and guidance for the decision of such cases.In this case, it is fully recognized by the court that the prior art has a strong demand as well as provide inspiration on forming crystalline forms of known active compounds and changing known crystalline forms. Compared with the process of creating a compound from scratch, the development of crystalline forms usually results from multiple attempts to use different crystallization methods for known active compounds. crystalline form inventions usually use the general properties of crystals known to those skilled in the art and conventional crystal preparation methods, which makes it extremely difficult for the technical means of such patents themselves to meet the requirement of non-obviousness in the inventiveness judgment. If the exclusive protection of an invention patent is granted merely because there are technical effects predictable by those skilled in the art, it is obviously inconsistent with the contribution made by the inventor to the prior art. There have always been different understandings in practice on how to consider the role played by the technical effects of crystalline forms in the inventiveness judgment. The judgment of this case proposes the rule that to determine whether a crystalline form has achieved technical effects that make it inventive compared with the prior art, it is possible to consider whether the technical effects recorded in the specification are related to the finished medicine.The technical effects described should be specific rather than general physical and chemical properties, such as purity, melting point, and hygroscopicity. If the recorded technical effects are highly related to the finished medicine and the marketed drug uses this crystalline form, it can be considered that it has beneficial technical effects. Correspondingly, the crystalline form patent is inventive and should be protected by the Patent Law.This case is a typical example of Beijing Intellectual Property Court’s active implementation of the innovation-driven development strategy based on the judicial practice of the pharmaceutical and healthcare industry. For the inventiveness judgment of drug-related patents, within the framework of the current rules system, it is necessary to comprehensively consider the relationship between marketed drugs and technical effects, fully protecting the interests of patent holders. The specific judicial rules of this case are helpful to promote the continuous innovation and development of the pharmaceutical industry, thus providing judicial support for ensuring the accessibility of medicines for the people and promoting the implementation of the Healthy China Strategy.

Case Ⅲ: Administrative Litigation Case Involving Invalidation of the “Dou Hai Yin” Trademark Right——Recognizing the Core Service Trademark of XX Internet Platform Enterprise as Well-Known1. Case InformationPlaintiff: Beijing XX Network Technology Co., Ltd. (hereinafter referred to as “XX Network Company”)Defendant: National Intellectual Property AdministrationThird Party: Shanghai XX Technology Co., Ltd. (hereinafter referred to as “XX Technology Company”)2. Basic FactsXX Technology Company applied for registration of the trademark “Dou Hai Yin” on August 31, 2018, which was approved for use in Class 39 services including “travel reservations.” On January 4, 2022, XX Network Company filed an invalidation request on the grounds that the disputed trademark violated Article 13 of the Trademark Law of the People’s Republic of China (prohibition against imitation of well-known trademarks). The National Intellectual Property Administration reviewed the case and determined that the “Dou Yin” trademark claimed by XX Network Company has a short period of use and insufficient evidence to prove it had achieved well-known status. It thus ruled to maintain the disputed trademark. XX Network Company refused to accept the ruling and filed an administrative lawsuit with the Beijing Intellectual Property Court. The court held in its first-instance judgment that although the “Dou Yin” trademark had been used for less than two years before the application date of the disputed trademark, the Dou Yin App had experienced explosive growth with short videos and social platforms as the core business since its launch in September 2016. By June 2018, it had become the top domestic short-video platform with a market penetration rate of 29.8%, reached over 500 million monthly active users (MAU) by July 2018, and accumulated over 3.1 billion total downloads by September 2018. In this case, XX Technology Company used promotional slogans such as “Check-in with Dou Yin,” demonstrating obviously malicious intent to free-ride on XX Network Company’s goodwill. So the “Dou Hai Yin” trademark should be deemed an imitation of “Dou Yin,” violating paragraph 3 of Article 13 of the Trademark Law. The Beijing Intellectual Property Court revoked the administrative ruling. The National Intellectual Property Administration filed an appeal against the decision, and the Beijing High People’s Court issued a final judgment rejecting the appeal and upholding the original judgment.3. Judgment GistWhen determining whether a trademark in the internet sector has achieved well-known status, courts must fully consider the internet industry’s unique characteristics and comprehensively assess factors such as the actual use effects of the trademark, market coverage, user growth rate, and other multidimensional criteria to evaluate whether the trademark meets the standard of being “widely recognized by the relevant public.”4. Typical SignificanceThe platform economy has emerged as a pivotal engine driving the digital transformation of the real economy and unleashing new-quality productive forces. Platform enterprises rapidly accumulate market reputation through technological innovation and business model updates, with their highly influential brand value in particular becoming a core competitiveness driving innovative development. As the trademark of these enterprises hold enormous commercial value, the more well-known a trademark becomes, the more likely it is to be targeted for malicious registration or free-riding.In China’s trademark registration system, protection for registered trademarks is confined to identical or similar goods/services. To combat cross-class malicious registrations, rights holders must prove their trademark has achieved “ wide recognition by the relevant public” to obtain cross-class protection for a well-known trademark. A well-known trademark, as the highest embodiment of corporate goodwill, represents consumers’ utmost trust in product quality and service standards—it is not merely an honorary title. In judicial practice, courts apply the principles of “ case-by-case determination” “passive protection” and “ protection as needed” to dynamically examine well-known trademark recognition. This approach balances precise strikes against cross-class bad-faith registrations with avoiding over-expansion of protection that could stifle market innovation. This case establishes adjudication rules for the recognition and protection of well-known trademarks in the internet sector:First, Significantly Shortening the Traditional Time-in-Use Requirement for Well-Known Status. Under the Provisions on the Recognition and Protection of Well-Known Trademarks issued by the former State Administration for Industry and Commerce, evidence proving a registered trademark’s well-known status must demonstrate at least three years of registration or five years of continuous use. In this case, the National Intellectual Property Administration initially denied recognition primarily because the “Dou Yin” trademark had been in use for a short period before the disputed trademark’s application. The judgment of this case which is based on the trademark law and judicial interpretations pointed out that with the innovative advantages of short video content distribution and algorithmic recommendation mechanism, Dou Yin APP has shown exponential growth in users and downloads in a short period of time, and rapidly accumulated a wide user base and market influence, and the cycle of its trademark popularity formation has been significantly shortened. If the traditional length-of-use requirement of the recognition standard is applied mechanically, it will be inconsistent with the development law of the Internet industry and the actual influence of the trademark.Second, Deepening Analysis of Well-Known Status Recognition in the Traffic Era. With the popularization of the Internet, short videos, artificial intelligence and other technologies, it has become a common business model for merchants to obtain economic benefits by attracting public attention. This case combines the characteristics of the “attention economy” of the Internet with an in-depth analysis of the considerations for the determination of well-known trademarks as stipulated in Article 14, Paragraph 1 of the Trademark Law of the People’s Republic of China. Beijing Intellectual Property Court holds that important indicators with the characteristics of the internet industry, such as the number of daily and monthly active users, average online duration, and market penetration rate, should be used as the basis for determining “the degree of recognition among relevant public.” Taking into account the characteristics of the internet environment, such as fast information dissemination, wide reach, tendency for explosive growth, and the common revenue model in the internet industry where users are acquired for free and income is generated through advertising and other means, the Court will assess adjudication factors such as “duration of continuous use” and “promotional efforts.”Third, Reasonably Defining the Scope of Protection for Internet Well-Known Trademarks. In this case, XX technology company, as an Internet practitioner providing travel information and other services through the Internet platform, used the trademark “Dou Hai Yin”with obvious intention of imitating and climbing, objectively weakened the identification function of the company’s trademark “Dou Yin”, improperly seized the goodwill resources legally accumulated by others, and constituted a substantial damage to the rights and interests of well-known trademarks. Therefore, it was determined that the trademark of the platform Company has reached the status of well-known, and the cross-class protection was in line with the principle of case-by-case and on-demand determination.This case provides clear judicial guidance for recognizing well-known trademarks in the internet sector, demonstrating courts’ firm support for the healthy development of high-value brands. By reasonably defining the boundaries of well-known trademark protection and regulating competition in the digital economy, it also guides platform enterprises and tech innovators to enhance trademark strategy and protection awareness, offering tangible judicial safeguards for high-quality development of new productive forces.

Case Ⅳ: Trademark Infringement and Unfair Competition Dispute Involving the “Lao Ban” Mark— Crackdown on Full-Chain Counterfeit Trademark Infringement1.Case InformationPlaintiff: Hangzhou X Electric Co., Ltd. (hereinafter referred to as “X Electric Company”)Defendants: Chaozhou X Ceramics Factory (hereinafter referred to as “X Ceramics Factory”), Chaozhou X Intelligent Technology Co., Ltd. (hereinafter referred to as “X Tech Company”), Lü X, Chen X, and Wu X2.Basic FactsThe plaintiff, X Electric Company, is the exclusive owner of the registered trademark “Lao Ban”, which is approved for use on Class 11 goods including kitchen range hoods. The five defendants, via multiple business entities including X Ceramics Factory (a sole proprietorship operated by Chen X), X Tech Company (jointly held by the married couple Lü X and Wu X), with other entities such as a Guangdong-based kitchen and bath company (which was suggested to be deregistered during litigation) and a Hong Kong-registered company solely directed by Lü X and in their individual capacities, used the marks “Lao Ban” “LAOBAN WEIYU” and “www.LAOBAN WEIYU.net” on sanitary ware products such as toilets, showers, and sinks. Meanwhile, the Defendants repeatedly used the term “Lao Ban” in their company names, personal or corporate account names, and store names. The plaintiff alleged that the collective actions of the five defendants infringed its exclusive trademark rights and constituted acts of unfair competition. Accordingly, it sought injunctive relief and joint compensation of RMB 5 million for economic losses and RMB 290,000 for reasonable expenses. Upon trial, Beijing Intellectual Property Court found that the five defendants had engaged in trademark infringement and unfair competition, and ordered them to cease the infringing activities and jointly pay the plaintiff RMB 5 million in damages and RMB 150,000 in reasonable costs.The defendants appealed, but Beijing High People’s Court dismissed the appeal and upheld the original judgment.3.Judgment GistWhere a company shareholder deregisters a company during litigation without legally liquidating it and has made relevant commitments at the time of deregistration, the shareholder shall bear corresponding legal liability for the company’s pre-deregistration acts of infringement.If a company committing the infringement was jointly funded by a married couple during their marriage, and no proof or agreement of property division exists between them, the company’s ownership may be deemed substantively unified. Accordingly, in line with rules applicable to single-member limited liability companies, the shareholder couple may be held jointly liable with the company for the infringement-related debts.4.Typical SignificanceAs a core intellectual property asset of a business, a trademark symbolizes its market competitiveness and serves as a vital tool for distinguishing the source of goods and services, building commercial reputation, and establishing brand recognition among consumers. The protection of trademark rights lies at the heart of China’s Trademark Law and is a key aspect of intellectual property protection. It plays a critical role in fostering a sound business environment and safeguarding fair market competition. Beijing Intellectual Property Court has jurisdiction over first-instance civil cases involving the recognition of well-known trademarks within Beijing, as well as other second-instance civil trademark cases. Since its establishment, the court has adjudicated over 3,200 first- and second-instance trademark infringement cases. In adjudicating such cases, the Court has consistently applied trademark laws and judicial interpretations with rigor and accuracy, distilled judicial principles from individual cases and unified standards of adjudication, adhering firmly to the principle of “strict protection” and continuously strengthening judicial safeguards for trademark rights.The development of new technologies and new business models has posed challenges to the legal system for trademark protection. Especially in the context of the digital economy and the diversification of commercial entities, the hidden and interconnected characteristics of trademark infringement subjects have become increasingly prominent. How to correctly understand the legislative intent and legal provisions, accurately identify trademark infringement behaviors that involve novel forms and complex associations, and ensure that all types of entities maliciously engaging in infringement along the entire chain bear corresponding legal liabilities—so as to create an effective deterrent against trademark infringement—is a critical issue worthy of attention and study in the adjudication of such cases. In this respect, the present case has made a valuable exploration and provides effective solutions to difficult judicial issues such as the determination of joint infringement and the attribution of infringement liability in trademark disputes.Based on the correct identification of the trademark infringement act, the judgment in this case adopts a penetrating adjudication approach, and employs a combination of institutional measures such as piercing the veil of shareholder liability and expanding joint and several liability. These measures significantly increase the cost of trademark infringement and effectively curb full-chain infringement behaviors that exploit legal loopholes to construct “firewalls” of liability, thus preventing infringers from concealing their identity and escaping responsibility.This case made meaningful breakthroughs in the following aspects and provided substantive guidance for resolving complex issues in trademark infringement disputes.Firstly, Piercing the Corporate Veil to Address “Shell Company” Infringement. According to the basic theory of company law, each shareholder of a limited liability company shall be liable for the company to the extent of the capital contribution subscribed for by it. In intellectual property infringement lawsuits, including those involving trademark infringement, an increasing number of infringing parties have used this fundamental principle of company law as a shield to evade liability by establishing companies—sometimes even cross-border or across different jurisdictions—they provide a “legal shell” for actual infringers to escape liability. The judgment in this case creatively applies Article 20 of the Provisions of the Supreme People’s Court on Several Issues Concerning the Application of the Company Law of the People’s Republic of China (II) to clearly define the scope of liability borne by shareholders who carry out simplified deregistration of a company without liquidation during the course of litigation. During the proceedings of this case, Chen X and Wu X, the shareholders of a Guangdong-based kitchen and bath company, implemented a simplified deregistration. Although formally extinguished the company’s legal status, the judgment pierced the corporate veil by examining the correlation between the shareholders’ signed commitment letters and their undertakings to assume debt liability, thereby holding the shareholders accountable. This effectively curbed the malpractice of actual infringers maliciously deregistering companies to avoid debts, and imposed punishment on infringing acts that exploit the formation and unlawful deregistration of companies to achieve a “getaway” from liability.Secondly, establishing a judicial standard of recognizing spouse-owned companies as sole proprietorships and refining the evidentiary rules for asset commingling. When determining the liability of the defendant, the Tech Company, the court went beyond the literal interpretation of Article 63 of the Company Law of the People’s Republic of China (2018 Amendment), and, in light of the joint shareholding by the spouses and the absence of any property division, held that the entirety of the company’s equity essentially derived from a single property interest, which was jointly owned and exercised as a single property right, with the equity interest exhibiting substantive unity and alignment of economic interests, thereby construing the company as a de facto single-shareholder limited liability company, and, pursuant to the principle of asset commingling, imposed joint and several liability on both spouses—the two shareholders—for the infringing acts committed by the company. This judgment established a judicial review standard that infers asset commingling from the common origin of shareholding, thereby effectively curbing infringing conduct that seeks to evade legal liability through intricate equity structures.Thirdly, establishing a framework for joint liability among related entities to crack down on industrial-scale infringement. In response to the coordinated infringing acts conducted by five defendants across different regions and legal entities, the case adopted a comprehensive adjudicative approach combining “behavioral relevance” and “concerted intention,” which involved examining factual elements such as cross-shareholding among the entities and shared trademark usage, and further relied on evidentiary chains including trademark licensing arrangements and coordinated online-offline sales activities among the defendants, to ascertain their shared intent to commit joint infringement. The adjudicative reasoning provides valuable guidance in resolving the complex issue of establishing joint infringement across a fragmented chain of “manufacturing–sales–brand operation.”This judgment systematically applied a multi-dimensional set of legal instruments, including the Company Law, Trademark Law, and the Civil Code, and achieved three major breakthroughs in the judicial determination of trademark infringement subjects: a shift from reviewing individual entities to examining related parties, an elevation from formal compliance assessment to substantive illegality determination, and an evolution from imposing individual liability to regulating joint and several liability. This innovation in adjudicative philosophy not only enhances the judicial protection of trademark rights, but also serves as a paradigm for establishing a robust regime of strict intellectual property protection.

Case V : Copyright Infringement Dispute involving over a hundred paintings that allegedly plagiarized works including Fallen Leaves.——Determination of Copyright Infringement of Artworks1. Case InformationAppellant (the defendant in the first instance): Ye XXAppellee (the plaintiff in the first instance): Xi XX2.Basic FactsThe Plaintiff Xi XX, a Belgian painter, alleged that the Defendant Ye XX had plagiarized over a hundred paintings created since 1993 over a span of 25 years, including artworks such as Fallen Leaves to which the Plaintiff held copyright. The Beijing Intellectual Property Court, after conducting a holistic comparison of the accused infringing paintings with the 13 copyrighted artworks involved in the case, along with comparative analyses of partial element combinations and individual element analyses, concluded that the 122 accused infringing paintings exhibited substantial similarity to the 13 copyrighted artworks in terms of visual artistic effects. Consequently, the court ruled that Ye XX’s acts of creating, publishing, and auctioning the disputed paintings infringed Xi XX’s exclusive rights to the 13 copyrighted artworks, including reproduction rights, modification rights, attribution rights, and distribution rights. Accordingly, the Beijing Intellectual Property Court ordered Ye XX to cease the infringement, make a public apology, rectify adverse effects, and compensate for economic losses amounting to 5 million RMB yuan. Ye XX filed an appeal, but the Beijing High People’s Court dismissed the appeal and upheld the original judgement.3.Judgment GistTo determine whether a work of art constitutes substantial similarity, it is generally assessed through a holistic examination and comprehensive evaluation of the artistic expression embodied in the work. This process focuses on visual characteristics such as constituent elements, specific expressions and the overall visual effect, which collectively define the work’s creative manifestation. If the differences between two artworks are merely minor in their entirety to the extent that an ordinary observer would tend to overlook such distinctions unless intentionally searching for them, such works may be deemed substantially similar.When a large number of copyrighted works and allegedly infringing works are involved in the comparison, all works under dispute should be considered holistically. Meanwhile, factors such as the author’s creative history, methods, and style should be comprehensively evaluated to determine of the extent of infringement, which serves as the basis for establishing the standards for damages compensation.4. Typical SignificanceArtworks carry the cultural connotations and artistic styles of a specific era and are an important component of the cultural industry. Protecting the copyright of artworks not only safeguards and inspires creators but also is of significant importance for promoting the standardized development of the cultural and artistic sector and enhancing a nation’s cultural soft power. This case is a typical copyright infringement case which clarifies two aspects of judicial rules: Ideas and expressions in artworks should be distinguished based on creative principles and characteristics, and judgment of substantial similarity should take into account the visual imagery characteristics of artworks.First, considerations regarding the differentiation between ideas and expressions in artworks.

The first consideration is the creative principles of artworks. The creative process of artworks is a gradual process of transforming ideas into expressions. Before the final completion of artworks, authors typically engage in ideational activities such as material collection and creative conceptualization. These mental processes generally extend from before the initiation of the creative act through the entire creative journey, encompassing the author’s subjective observations of specific objects, social phenomena, and personal life experiences, as well as their individual perspectives and emotional insights. Additionally, the final artistic outcome is closely intertwined with the author’s technical proficiency, artistic vision, and aesthetic sensibilities. Through external expressions in specific forms, the author finalizes and publicizes the aesthetic imagery within their consciousness, enabling others to appreciate, evaluate, and understand their artistic attainments and aesthetic preferences through the medium of the artwork. Objectively, this process also defines the scope of expressions protected by copyright.The characteristics of artworks should also be considered. According to the definition in the Implementing Regulations of the Copyright Law, the expression of an artwork primarily lies in the artistic representation objectively presented through the organic integration of aesthetic elements such as composition, lines, colors, and forms. The artistic image of an artwork is manifested as a visual image, characterized by visual immediacy, definiteness, and visibility. Copyright protection for artistic works focuses more on the external form of expression rather than the specific depicted content, which distinguishes it significantly from the protection of literary works that places greater emphasis on the substantive written content.Second, the criteria for determining substantial similarity between artworks.In copyright infringement disputes involving artworks, determining whether there is substantial similarity between the allegedly infringing works and the copyrighted works should involve comparing whether the choices, selections,arrangements, and designs made by the author in the expression of the artworks are the same or similar. As previously mentioned, artistic works are a form of visual art, and thus the external form of expression they embody constitutes the essence of their value. While different types of artistic works may cater to audiences with varying characteristics and levels of appreciation, once an artwork is publicly disclosed, it primarily targets the general public for appreciation and evaluation.Therefore, the determination of whether two artistic works constitute substantial similarity should be based on the perspective of ordinary observers. This involves a holistic assessment and comprehensive judgment of the visual characteristics of both the copyrighted artwork and the allegedly infringing artwork. If the two works only exhibit minor differences in details that would only be noticeable to ordinary observers through deliberate searching and comparison, then it can be concluded that the works constitute substantial similarity.After the judgment took effect, the defendant voluntarily issued a public apology in Legal Daily, a Chinese newspaper, marking the resolution of a five-year, cross-border copyright dispute over artistic works. The judgment undertook a total of 303 comparative analyses between over 100 allegedly infringing artworks and the copyrighted works, examining them across multiple dimensions including compositional elements, modes of expression, and overall aesthetic effect, ensuring no detail was overlooked. On this foundation, the court conducted a comprehensive assessment of potential infringement by integrating factors such as the author’s creative history, methodologies, and stylistic idiosyncrasies. Through this process, it fastidiously demarcated the boundary between permissible artistic reference and infringing plagiarism in artworks. The judgment ultimately safeguarded the copyright rights of the Belgian artist in strict accordance with legal provisions. While providing valuable guidance for the adjudication of similar cases, the judgment also demonstrates a judicial stance of equal protection for the lawful rights and interests of foreign entities, thereby conveying the spirit of justice, transparency, and openness inherent in the rule of law.

Case VI: The First Case on Administrative litigation Involving Anti-Monopoly Review of Concentrations Between Undertakings——First Judicial Clarification of Concentrations Between Undertakings Review Standards

[Omitted]

Case VII: The First Case Involving Validity Confirmation of Data Intellectual Property Registration Certificates in an Anti-Unfair Competition Dispute——First Judicial Recognition of the Legal Effect of a Data Intellectual Property Registration Certificate1. Case InformationAppellant (Defendant in the First Instance): Yin X (Shanghai) Technology Co., Ltd. (hereinafter referred to as Yin X Company)Appellee (Plaintiff in the First Instance): Shu X (Beijing) Technology Co., Ltd. (hereinafter referred to as Shu X Company)2. Basic FactsShu X Company, having lawfully obtained authorization, collected a Mandarin Chinese speech dataset totaling 1,505 hours and registered it with a Data Intellectual Property Registration Certificate. Shu X Company sued Yin X Company for providing a 200-hour subset of this dataset without permission, alleging infringement of data property rights, copyright, trade secrets, and unfair competition, and sought damages of over RMB 700,000 yuan. The court of first instance ruled that the dataset constituted a trade secret and found Yin X Company liable for disclosing and using it unlawfully, ordering compensation of 102,300 RMB.Yin X Company appealed, arguing that the dataset had been open-sourced before the alleged conduct occurred and therefore lacked secrecy, which did not qualify as a compilation due to lack of originality, and the alleged conduct did not constitute unfair competition. The Beijing Intellectual Property Court, on appeal, held that the Data Intellectual Property Registration Certificate could serve as preliminary evidence of Shu X Company’s lawful acquisition and property interest in the dataset. However, since the dataset was publicly available, it did not meet the criteria for trade secret protection. Furthermore, the dataset’s selection and arrangement lacked originality and did not constitute a compilation.Nonetheless, Shu X Hui X Company invested significant technology, capital, and labor in collecting and organizing the data, resulting in commercially valuable entries that conferred competitive advantages and business opportunities. These interests deserved protection under the Anti-Unfair Competition Law. Yin X Company failed to follow the terms of the open-source license, violated commercial ethics, harmed Shu X Company ’ s interests and the competitive market order, and thereby committed an act of unfair competition under Article 2 of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law. The appellate court corrected the erroneous finding on trade secrets but upheld the lower court ’ s compensation ruling and dismissed the appeal.3.Judgement GistThe Data Intellectual Property Registration Certificate may serve as preliminary evidence of a data holder’s proprietary interest in the dataset and of the dataset’s lawful origin and collection. Without the data holder’s consent, no party may publicly disseminate a dataset lawfully and substantially collected by the holder. Where a data holder has open-sourced a dataset, whether a user complies with the license terms is a critical factor in assessing whether the use violates commercial ethics in the data services field.If the dataset is publicly available and features original selection or arrangement of content, it is preferably protected as a compilation under copyright law. If the dataset is not readily accessible to those in the relevant field, it may be protected as a trade secret. If the dataset is public and lacks originality in its selection or arrangement, it does not qualify for copyright or trade secret protection, but may be protected under Article 2 of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law depending on the circumstances.4.Typical SignificanceAs the digital economy becomes deeply integrated into production and daily life, data is increasingly recognized as a core production factor. Efficient circulation and secure protection of data are crucial for stimulating market innovation. The data registration system, by standardizing the registration of rights related to data ownership, processing, and commercialization, lays the groundwork for the market-based allocation of data resources. On one hand, it uses public disclosure and credibility mechanisms to clarify rights boundaries, reduce verification costs and legal risks in data transactions, and provide a “base map ” for cross-industry and cross-regional data flows. On the other, it recognizes and protects legitimate input by data processors, incentivizing real innovation in data collection, cleaning, and labeling, thereby promoting the transformation of data from a “resource” into an “asset.” This case is the first in China to examine the legal effect of a Data Intellectual Property Registration Certificate. The appellate judgment, guided by the policy directive in the “Opinions of the CPC Central Committee and the State Council on Establishing a Data Infrastructure System to Better Leverage the Role of Data as a Production Factor ” (the “ 20 Measures on Data ” ), which calls for “ exploring new approaches to data property rights registration,” responds to the regulatory needs of the data registration regime through judicial innovation, establishing a legal foundation for the healthy development of the data element market.In recent years, the Beijing Intellectual Property Court has handled a diverse and technically complex range of data rights cases, 95% of which involved unfair competition, covering emerging disputes like data scraping, trade secret protection, and open-source data and involving AI training datasets and speech datasets. The appellate ruling in this case establishes rules for judicial protection of data rights, especially in clearly defining the legal effect of registration certificates and guiding corporate data protection strategies.First, it affirms the preliminary evidentiary effect of Data Intellectual Property Registration Certificates. Such certificates can initially prove lawful possession and source legitimacy, unless rebutted by contrary evidence. However, this recognition must be understood in three ways: (1) the certificate’s effect is case-specific and rebuttable; (2) its weight depends on the registration agency’s qualifications, review standards, and content; and (3) data holders may assert rights by other means even without registration. This balanced approach both affirms the role of registration and preserves judicial restraint.Second, it establishes a tiered path for protecting enterprise data rights based on the dataset ’ s legal nature. Datasets with original selection or arrangement are protected by copyright law; non-public datasets meeting trade secret criteria fall under relevant unfair competition provisions; and public datasets lacking originality but involving substantial input may be protected under Article 2 of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law. In this case, although the dataset did not qualify as a trade secret due to its public nature, the court recognized Shu X Company’s lawful investment and certificate-based proof, and penalized Yin X Company’s breach of the open-source license under the unfair competition framework, establishing boundaries for “ethical use and respect for prior investment” in the use of public data.Third, it strengthens regulatory constraints on the circulation of open-source data. The ruling explicitly states for the first time that users must strictly comply with open-source license terms, and unlicensed commercial use constitutes unfair competition. This rule addresses the tension between free use and rights protection in an open-source context and establishes clear expectations for enterprises to unlock data value through open-source licenses by affirming that legitimate open-sourcing does not equate to relinquishing rights, while emphasizing that unauthorized commercial exploitation in violation of the agreement terms will still incur legal liability.This case marks a transition in China toward coordinated governance through data rights registration and judicial protection. It provides clear behavioral guidance for data processors and signals to the market that the development and utilization of data must occur within the rule of law. Legitimate rights are protected, and violations carry consequences. With continued accumulation of such judicial principles, China’s data element market is poised to develop into a legally regulated environment where “ registration has standards, transactions have legal grounds, and disputes have solutions,” laying a strong foundation for high-quality growth in the digital economy.

Case VIII: “FL218” Corn Plant Variety Right Invalidity Administrative Dispute——Clarifying Novelty, Specificity Standards and Burden of Proof in Plant Variety Invalidity Procedures1. Case InformationPlaintiff: Hui X Seed Industry Co., Ltd. Of ZunYi city, GuiZhou Province. (hereinafter referred to as Hui X Company)Defendant: The Reexamination Board for New Varieties of Plants, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (hereinafter referred to as The Reexamination Board for New Varieties of Plants)Third Party: Hubei Kang X Seed Industry Co., Ltd.2. Basic FactsThe disputed variety in this case is a new corn variety named “FL218” for which Company K holds the plant variety rights. Hui X Company filed a request for invalidation with the Reexamination Board for New Varieties of Plants, which made the decision to maintain the validity of the disputed plant variety right. Hui X Company disagreed and filed an administrative lawsuit with the Beijing Intellectual Property Court, arguing that the disputed variety is the same as the parent varieties of several approved corn varieties, such as “Eyu 16” and that prior to the application date, the disputed variety had already been widely produced and sold, and was used as a parent to breed other corn varieties. The other varieties bred from it were also widely produced and sold, thus the involved variety had lost its distinctness and novelty, therefore the decision was incorrect. Furthermore, the Reexamination Board for New Varieties of Plants did not accept Hui X Company’s application to identify that the disputed variety and other varieties ’ parent plants were the same variety, claiming procedural violations. After hearing the case, the Beijing Intellectual Property Court found that the procedures were not improper, and the conclusion of the decision was correct, thus dismissing Hui X Company ’ s claim. Hui X Company appealed, and the Supreme People’s Court made a final ruling, dismissed the appeal and upheld the original judgment.3. Judgement GistThe examination of the novelty of a new plant variety involves determining whether the variety was sold or promoted prior to the application date. The act of using a variety as a parent to breed hybrids does not constitute commercialization. Furthermore, commercialization activities pertain to the protected variety itself, not to hybrids bred using that variety as a parent. Therefore, the sale of hybrids, in principle, cannot be regarded as the sale of the parent variety.The examination of distinctness for a new plant variety determines whether the variety is clearly distinguishable from known varieties. In invalidation proceedings for plant variety rights, the invalidation petitioner bears the burden of proof regarding the existence of clear distinctness, and the Reexamination Board for New Varieties of Plants is not obligated to conduct investigations.4. Typical SignificanceSeeds are the “ chips ” of agriculture, and the seed industry is a core national industry that plays a crucial role in agricultural stability and national food security. Intellectual property protection in the seed industry is vital for its revitalization and prosperity, and it is an indispensable part of the intellectual property protection system. Plant variety rights, as a major component of intellectual property rights in the seed industry, focus on the protection of reproductive materials, namely seeds. It has been proven that granting exclusive rights to seeds that are clearly distinguishable from other known varieties and have not been sold or promoted before the application date—thus possessing the characteristics of specificity and novelty as stipulated in the Seed Law of the People’s Republic of China — strengthens intellectual property protection for plant varieties, providing breeders with a fair economic return for their innovative contributions. This, in turn, effectively increases breeding activity and encourages breeding innovation.In the legal system governing plant variety rights, the authorization and invalidity review of plant variety rights are key procedures. The Reexamination Board for New Varieties of Plants is the administrative authority responsible for conducting these reviews. Whether the variety applicant, the variety right holder, or the party petitioning for invalidation of the plant variety right, all may file an administrative lawsuit with the Beijing Intellectual Property Court if they are dissatisfied with the decisions made by the Reexamination Board for New Varieties of Plants.The Beijing Intellectual Property Court, as the exclusive court with nationwide jurisdiction over this type of special and “ niche ” intellectual property administrative dispute, has established a multi-disciplinary technical fact-finding mechanism led by academicians from agricultural science institutions, and a specialized review system for seed industry cases. By leveraging the advantages of a specialized court, the court actively explores a judicial protection model for intellectual property in the seed industry that aligns with its unique characteristics, having heard a number of landmark administrative cases regarding plant variety right authorization and confirmation. This case is a typical example, and the judgment provides clear guidance on the standards for assessing novelty and specificity of plant varieties and the burden of proof in the plant variety invalidity process.Unlike the novelty requirement for patents, there is only one way to destroy the novelty of a new plant variety, namely through public sale or promotion in the market. This judgment starts from the intrinsic meaning of the novelty characteristic of new plant varieties and strictly adheres to the provisions of the Seed Law of the People’s Republic of China and the Regulations on the Protection of New Plant Varieties of the People’s Republic of China. It clarifies that sales and promotional activities should be accurately understood as actions that enable relevant technicians to obtain propagating materials in the market. The act of using propagating materials as parent plants to breed other hybrid varieties should not be broadly interpreted as sales or promotional activities. Furthermore, the sales or promotional activities that undermine novelty only apply to the protected variety itself, not to hybrid varieties bred using it as a parent.The “clear distinction” of a new plant variety from known varieties constitutes its distinctness. This distinctness must be scientifically demonstrated through field trial results. In this ruling, the court carefully examined the methods for proving distinctness, including the requirement to submit field test reports when applying for variety rights. It clarified that in invalidation proceedings, the party seeking invalidation bears the burden of proving that the disputed plant variety lacks distinctness, while the administrative authority is not obligated to conduct its own investigations. Simply requesting a field examination from the Plant Variety Review Board does not fulfill this burden of proof. By clarifying the allocation of the burden of proof, this decision helps standardize the review process for plant variety right invalidations.This judgment also serves as a reminder to industry participants that they must accurately understand the legal system surrounding plant variety protection. While legally protecting their innovative crops and commercial outcomes, they must also properly utilize the plant variety invalidity procedure, actively fulfilling their burden of proof, and discharging their evidentiary obligations in accordance with the law. This will help resolve disputes amicably and maintain the effective operation of the plant variety protection system, promoting the high-quality development of China’s seed industry and ensuring that the Chinese people always keep our food security firmly in our own hands.

Lamborghini Accused of Driving Away With Former Partner’s Trade Secrets

Prema Engineering S.r.l. (“Prema Engineering”) has accused automaker Automobili Lamborghini S.p.A. and Automobili Lamborghini America, LLC (collectively, “Lamborghini”) of stealing Prema Engineering’s intellectual property and trade secrets it supplies to Hypercars used in endurance racing.

In Prema Engineering S.r.l. v. Automobili Lamborghini S.p.A., filed in the United States District Court for the Western District of Texas, Austin Division, Prema Engineering alleges that in 2024, Lamborghini, while in a racing partnership with Prema Engineering and Iron Lynx racing team, stole Prema Engineering’s high-tech trade secret-protected steering wheel software in order to use it in Lamborghini’s new racing partnership with Riley Motorsports, a competitor of Prema Engineering and Iron Lynx.

Prema Engineering alleges that Lamborghini entered into a partnership with the Iron Lynx racing team, pursuant to which Lamborghini sold two Lamborghini-manufactured Hypercars to the Iron Lynx team and agreed to provide spare parts and other supply-related assistance for the Hypercars. Under the partnership, Prema Engineering was the exclusive provider of all servicing, maintenance, engineering and technical support to the Iron Lynx racing team.

The steering wheel software at the center of the action involves a “proprietary package of computer code developed by engineers and technicians at Prema Engineering,” referred to as steering wheel setups (“Setups”), that Prema Engineering “developed and customized” using its team’s forty years of experience in formula and endurance racing. Per the Complaint, the “Setups are customized for each racetrack and race session, and they enable the collection and processing of data collected from the Hypercars while they are running.” The Setups are also used to customize the steering wheel to the specific driver to implement during a race “the team’s strategies and maximize the Hypercar’s performance.”