Is An LLC’s Membership List A Trade Secret?

Yesterday’s post considered one of several matters raised on appeal in Perry v. Stuart, 2025 WL 1501935. The case involves a former member’s demand for inspection of records of a California limited liability company. Another issue raised in the appeal was whether the trial court erred in its finding that the LLC’s member list must be redacted prior to production because it is a trade secret.

The California Revised Uniform Limited Liability Company Act requires an LLC to keep, among other things, a current list of the full name and last known business or residence address of each member and of each transferee set forth in alphabetical order, together with the contribution and the share in profits and losses of each member and transferee. Cal. Corp. Code § 17701.13(d)(1). The RULLCA further provides that each member, manager, and transferee has the right, upon reasonable request, for purposes reasonably related to the interest of that person as a member, manager, or transferee, to inspect and copy during normal business hours any of the records required to be maintained pursuant to Section 17701.13. Cal. Corp. Code § 17704.10(b)(1).

The courts found that the membership list was a protectible trade secret, as defined under Section 3426.1 of the California Civil Code. Thus, the question was which code prevailed. The Court of Appeal concluded that the Civil Code took precedence as the more specific statute and thus the trial court had not erred in ordering the redaction of the membership list. The Court did not articulate why the Civil Code statute was more specific other than to note that trade secrets are a subset of business information. However, it is certainly arguable that membership list is an even smaller subset of business information and that the RULLCA provision is even more specific (i.e., detailing the exact information to be maintained) than the general Civil Code definition.

Plausibly Alleging Access Requires More Than Social Media Visibility

The US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit affirmed a district court’s dismissal of a copyright action, finding that the plaintiff failed to plausibly allege either that the defendant had “access” to the work in question merely because it was posted on social media, or that the accused photos were substantially similar to any protectable elements of plaintiff’s photographs. Rodney Woodland v. Montero Lamar Hill, aka Lil Nas X, et al., Case No. 23-55418 (9th Cir. May 16, 2025) (Lee, Gould, Bennett, JJ.)

The dispute arose between Rodney Woodland, a freelance model and artist, and Montero Lamar Hill, also known as Lil Nas X, a well-known musical artist. Woodland alleged that Hill infringed on his copyright by posting photographs to his Instagram account that bore a striking resemblance to images Woodland had previously posted. Woodland claimed that the arrangement, styling, and overall visual composition of Hill’s photos closely mirrored his own, asserting that these similarities constituted unlawful copying of his original work.

Woodland’s original images had been publicly shared on his Instagram account, where he maintained a modest following. He did not allege any direct contact or interaction with Hill or his representatives, nor did he claim that Hill had acknowledged or referenced his work. Instead, Woodland’s claim rested on the contention that the similarities between the two sets of photographs were so substantial that copying could be inferred. In his complaint, Woodland asserted that Hill had access to his publicly posted images and that the degree of similarity supported a finding of unlawful copying. The district court dismissed the complaint, holding that Woodland failed to plausibly allege either access or substantial similarity. Woodland appealed.

The Ninth Circuit affirmed, agreeing with the district court that Woodland failed to satisfy the pleading standard necessary to survive a motion to dismiss. The Ninth Circuit explained that to state a viable claim for copyright infringement, a plaintiff must alleged both the fact of copying and the unlawful appropriation of protected expression. The Court found that Woodland failed to establish either element.

The Ninth Circuit considered two principal legal issues:

Whether Woodland sufficiently alleged that Hill had access to Woodland’s copyrighted works

Whether the photographs posted by Hill were substantially similar to Woodland’s photographs in their protectable elements under copyright law

On the issue of access, the Ninth Circuit found that the merely alleging availability of Woodland’s photos on Instagram did not, by itself, plausibly demonstrate that Hill had seen them. The Court noted that in the era of online platforms, “the concept of ‘access’ is increasingly diluted.” And while that might make it easier for plaintiffs to show “access,” there must be a showing that the defendants had a reasonable chance of seeing that work under the platform’s policies. The mere fact that Hill used Instagram and Woodland’s photos were available on the same platform raised only a “bare possibility” that Hill viewed the photos. Woodland had not plausibly alleged that Hill “followed, liked, or otherwise interacted” with Woodland’s posts or other similar accounts – the content merely being of a similar subgenre, even if true, was not sufficient. Without additional factual allegations suggesting that Hill had encountered Woodland’s work, the Court found that there was no reasonable basis to infer access.

Woodland also alleged that Hill copied 12 of Woodland’s photographs, characterizing the case as one of “serial infringement.” The Ninth Circuit rejected these allegations, finding that the number of allegedly copied images did not constitute direct evidence of access, nor was it dispositive of infringement. The Court noted that there was no precedent tilting the scale in Woodland’s favor based solely on the volume of alleged copying. Accordingly, the Court concluded that Woodland failed to plausibly allege a “reasonable possibility” that Hill had viewed his work.

On the issue of substantial similarity, the Ninth Circuit conducted a qualitative comparison of the two sets of photographs and found them lacking in protectable overlap. While both featured similar themes, such as styling, lighting, and pose, these elements were deemed either unoriginal or too general to warrant protection under copyright law. The Court emphasized that copyright does not extend to ideas, concepts, or unoriginal components such as generic backdrops, common poses, or standard photographic techniques. Furthermore, the Court found that the selection and arrangement of elements in the photographs was not sufficiently unique to establish a valid claim for infringement of elements protectable by copyright.

China’s Supreme People’s Court Designates Record-Setting Trade Secret Case as a Typical Case

On May 26, 2025, China’s Supreme People’s Court (SPC) released the “Typical cases on the fifth anniversary of the promulgation of the Civil Code” (民法典颁布五周年典型案例) including one intellectual property case – the record-setting 640 million RMB trade secret case of June 2024. While the decision was a hollow victory as the defendant is insolvent and has not paid any damages, designation as a typical case may encourage lower courts to award higher damages in future trade secret cases. While the parties are unnamed, the plaintiff is Geely Holding Group and the defendant is WM Motor.

As explained by the SPC:

III. “Strict protection” and “high compensation” to actively create an environment that encourages innovation – Ji XX Company et al. v. Wei XX Company et al. Case of infringement of technical secrets

1. Basic Facts of the Case

Nearly 40 senior managers and technical personnel of Ji XX Company and its affiliated companies resigned and went to work for Wei XX Company and its affiliated companies, of which 30 joined the company immediately after resigning in 2016. In 2018, Ji Co. discovered that Wei Co. and the two companies used some of the above-mentioned resigned personnel as inventors or co-inventors, and applied for 12 patents using the new energy vehicle chassis application technology and 12 sets of chassis parts drawings and technical information carried by digital models (hereinafter referred to as “the technical secrets involved in the case”) that hey learned from their prior employer. In addition, the Wei EX series electric vehicles launched by Wei Co. were suspected of infringing the technical secrets involved in the case. Ji Co. filed a lawsuit with the first instance court, requesting that Wei Co. be ordered to stop the infringement and compensate for economic losses and reasonable expenses totaling 2.1 billion RMB.

2. Judgment Result

The effective judgment held that this case was an infringement of technical secrets caused by the organized and planned use of improper means to poach technical personnel and technical resources of new energy vehicles on a large scale. Through overall analysis and comprehensive judgment, Wei Co. obtained all the technical secrets involved in the case by improper means, illegally disclosed part of the technical secrets involved in the case by applying for patents, and used all the technical secrets involved in the case. Therefore, the judgment is: unless the consent of Ji Co. is obtained, Wei Co. shall stop disclosing, using, or allowing others to use the technical secrets involved in the case in any way, and shall not implement, permit others to implement, transfer, pledge, or otherwise dispose of the 12 patents involved in the case; all drawings, digital models, and other technical materials containing the technical secrets involved in the case shall be destroyed or handed over to Ji Co.; the judgment and the requirements for stopping infringement shall be notified to Wei Co. and all its employees, affiliated companies, and relevant component suppliers by means of announcements, internal company notices, etc., and the relevant personnel and units shall be required to sign a letter of commitment to maintain secrecy and not infringe, etc.; considering that Wei Co. has obvious intention to infringe, the circumstances of infringement are serious, and the consequences of infringement are serious, double punitive damages shall be applied to Wei Co.’s infringement profits from May 2019 to the first quarter of 2022, and Wei Co. shall compensate Ji Co. for economic losses and reasonable expenses of about 640 million RMB. At the same time, it is made clear that if Wei Co. violates the obligation to stop infringement determined by the judgment, it shall pay the late performance fee on a daily basis or in one lump sum.

3. Typical significance

General Secretary Xi Jinping profoundly pointed out that protecting intellectual property rights is protecting innovation. Strengthening judicial protection of intellectual property rights is an inherent requirement and important guarantee for the development of new quality productivity. In this case, the People’s Court, in accordance with the relevant provisions of the Civil Code, based on the determination of infringement of technical secrets, while applying punitive damages in accordance with the law, also actively explored the specific way to bear civil liability for stopping infringement and the calculation standard of delayed performance of non-monetary payment obligations, which promoted the renewal of intellectual property trial concepts and innovation of judgment rules, fully demonstrated the clear attitude of strictly protecting intellectual property rights and the firm stance of punishing unfair competition, and was conducive to creating a legal business environment of honest operation, fair competition, and innovation incentives.

4. Guidance on the provisions of the Civil Code

Article 179 The main forms of civil liability include:

(1) cessation of the infringement;

(2) removal of the nuisance;

(3) elimination of the danger;

(4) restitution;

(5) restoration;

(6) repair, redoing, or replacement;

(7) continuance of performance;

(8) compensation for losses;

(9) payment of liquidated damages;

(10) elimination of adverse effects and rehabilitation of reputation; and

(11) extension of apologies.

Where punitive damages are available as provided by law, such provisions shall be followed.

The forms of civil liability provided in this Article may be applied separately or concurrently.

Article 1168: Where two or more persons jointly commit an infringement and cause damage to others, they shall bear joint and several liability.

The original text, including four other Civil Code Typical Cases, can be found here (Chinese only).

Trade Secret Law Evolution- Episode 77: Establishing Irreparable Harm and Likelihood of Success [Podcast]

In this episode, Jordan breaks down a recent ruling from the Northern District of New York that addresses what to do and not to do to establish the elements of irreparable harm and likelihood of success for a motion to enjoin trade secret misappropriation.

Biopharmaceutical Patent Litigation: Regeneron’s Defense Against Biosimilar Launches

This case[1] involves an appeal from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.’s (Regeneron) efforts to prevent defendants from marketing biosimilar versions of EYLEA®, a drug used to treat eye diseases, by asserting patent infringement. In particular, the Federal Circuit addressed issues of personal jurisdiction, preliminary injunctions, and patent validity.

Background

Regeneron holds a Biologics License Application (BLA) for EYLEA®, which contains a fusion protein called aflibercept that acts as a vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) antagonist. This drug is commonly used for treating angiogenic eye diseases through intravitreal administration. Regeneron also owns patents related to the formulation and use of this drug. In 2022, Samsung Bioepis (SB) and other companies filed for FDA approval of EYLEA® biosimilars, prompting Regeneron to file patent infringement lawsuits against SB and other defendants. The case was consolidated in the Northern District of West Virginia, where another defendant is incorporated.

In the district court, Regeneron sought preliminary injunctions against SB and other defendants to prevent the sale of biosimilars that allegedly infringed on Regeneron’s patents. The district court granted Regeneron’s motion for a preliminary injunction, finding that Regeneron was likely to succeed on the merits of its patent infringement claims. The court determined it had personal jurisdiction over SB based on SB’s filing of an abbreviated BLA (aBLA) and its plans for nationwide distribution of its biosimilar product. SB contested these findings, arguing against the court’s jurisdiction and the validity of the preliminary injunction. Subsequently, SB appealed the district court’s decisions to the Federal Circuit, challenging both the jurisdictional ruling and the grant of the preliminary injunction.

Issue(s)

Whether the West Virginia district court had personal jurisdiction over SB, a South Korean company, based on its interactions and agreements related to the U.S. market.

Whether Regeneron demonstrated a likelihood of success on the merits and the threat of irreparable harm, justifying the preliminary injunction against SB.

Whether SB raised substantial questions regarding the validity of Regeneron’s patents, particularly concerning obviousness-type double patenting and written description sufficiency.

Holding(s)

The Federal Circuit affirmed that the district court had personal jurisdiction over SB, as SB had established distribution channels for its biosimilar that included West Virginia.

The Federal Circuit upheld the preliminary injunction against SB, finding that Regeneron met all the necessary factors, including likelihood of success and irreparable harm.

SB did not raise a substantial question of invalidity under the doctrines of obviousness-type double patenting or lack of written description support.

Reasoning

Regarding personal jurisdiction, the Federal Circuit found that SB’s filing of an aBLA, coupled with its agreement with Biogen to distribute the biosimilar nationwide, constituted sufficient minimum contacts with West Virginia. The Court emphasized that SB’s plans for nationwide distribution, without excluding any states, further supported jurisdiction.

Regarding the preliminary injunction, the Federal Circuit evaluated the four relevant factors: likelihood of success on the merits, potential for irreparable harm, balance of hardships, and public interest. Regeneron demonstrated a likelihood of success given the strength of its patent claims and SB’s inability to present a substantial invalidity defense. The Court found that Regeneron would suffer irreparable harm through market share loss and price erosion if SB launched its biosimilar. The balance of hardships favored Regeneron because Regeneron would suffer significant market disruption and loss of goodwill if the biosimilar products were launched, whereas SB would not face comparable harm from a delay in entering the market, given that the injunction would only temporarily prevent their entry until the patent issues were resolved. And, finally, the public interest supported enforcing valid patent rights.

On the issue of obviousness-type double patenting, the Federal Circuit concluded the patent at issue was patentably distinct from the reference patent, particularly due to its specific stability and glycosylation limitations. Regarding written description, the Court held that the patent at issue’s specification adequately supported the claims, with sufficient disclosure of the claimed stability levels of glycosylation.

In conclusion, the Federal Circuit upheld the district court’s decision to grant a preliminary injunction against SB, affirming that personal jurisdiction was appropriate and that Regeneron was likely to succeed on the merits of its patent infringement claims. The Court found no substantial question of patent invalidity, reinforcing the strength of Regeneron’s patent rights against marketing biosimilar versions of EYLEA®. This decision underscores the importance of detailed patent specifications and robust patent rights in biopharmaceutical patent litigation.

FOOTNOTES

[1] Regeneron Pharms., Inc. v. Mylan Pharms. Inc., Amgen USA, Inc., Biocon Biologics Inc., Celltrion, Inc., Formycon AG, Amgen Inc., Samsung Bioepis (Defendant-Appellant) No. 2024-1965, 2024-1966, 2024-2082, 2024-2083 (Fed. Cir. Jan. 29, 2025)

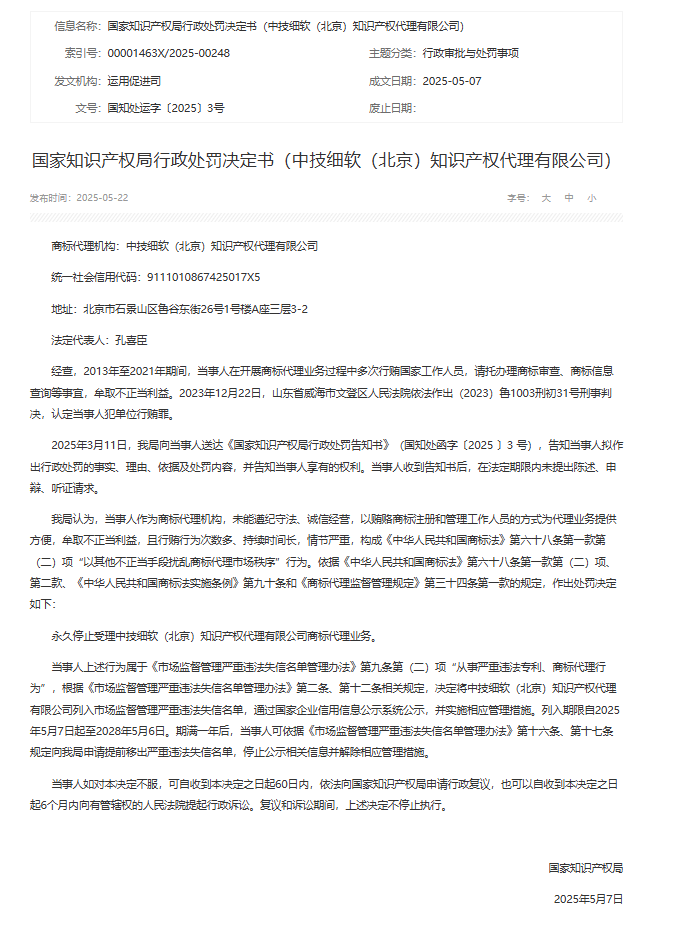

CNIPA Permanently Suspends Three Chinese Trademark Firms for Bribery

On May 22, 2025, China’s National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) released three administrative penalty decisions permanently suspending three trademarks firms from accepting trademark work. Per Tianyancha (geoblocked) and a court decision, one firm in particular was found to have bribed a CNIPA trademark examiner from 2013 to 2021 totaling 1.29 million RMB. The firm was criminally convicted and fined 100,000 RMB and the illegal gains of 1,382,680 RMB were seized.

A translation of one of the Decisions follows. The original text of the Decisions can be found here, here and here. A screen shot from Tianyancha can be found here courtesy of 知识产权界.

After investigation, it was found that from 2013 to 2021, the party bribed state officials many times in the process of carrying out trademark agency business, asking them to handle trademark examination, trademark information inquiry and other matters, and seeking improper benefits. On December 22, 2023, the People’s Court of Wendeng District, Weihai City, Shandong Province, rendered a criminal judgment (2023)鲁1003刑初31号 in accordance with the law, and found that the party was guilty of corporate bribery.

On March 11, 2025, our office served the party concerned with the “Notice of Administrative Penalty by the State Intellectual Property Office” (State Intellectual Property Office Letter [2025] No. 3), informing the party concerned of the facts, reasons, basis and content of the proposed administrative penalty, and informing the party concerned of the rights they enjoy. After receiving the notice, the party concerned did not make a statement, defense or request for a hearing within the statutory period.

Our bureau believes that the party concerned, as a trademark agency, failed to abide by laws and regulations and operate in good faith, and provided convenience for agency business by bribing trademark registration and management staff, and obtained improper benefits. Moreover, the bribery was frequent, lasted for a long time, and the circumstances were serious, constituting the act of “disrupting the trademark agency market order by other improper means” as stipulated in Article 68, paragraph 1, item (2) of the Trademark Law of the People’s Republic of China. In accordance with Article 68, paragraph 1, item (2) and paragraph 2 of the Trademark Law of the People’s Republic of China, Article 90 of the Regulations for the Implementation of the Trademark Law of the People’s Republic of China, and Article 34, paragraph 1 of the Regulations on the Supervision and Administration of Trademark Agencies, the following penalty decision is made:

Permanently stop accepting trademark agency business from Beijing Zhonglian Aizhi Intellectual Property Agency Co., Ltd.

The above-mentioned behavior of the party concerned falls under the provisions of Article 9, Item (2) of the “Administrative Measures for the List of Serious Illegal Dishonesty in Market Supervision and Administration”, “engaging in serious illegal patent and trademark agency behavior”. According to the relevant provisions of Article 2 and Article 12 of the “Administrative Measures for the List of Serious Illegal Dishonesty in Market Supervision and Administration”, it is decided to include Beijing Zhonglian Aizhi Intellectual Property Agency Co., Ltd in the list of serious illegal dishonest companies in Market Supervision and Administration, publicize it through the National Enterprise Credit Information Publicity System, and implement corresponding management measures. The inclusion period is from May 7, 2025 to May 6, 2028. After one year, the party concerned may apply to our bureau for early removal from the list of serious illegal dishonest companies in accordance with Articles 16 and 17 of the “Administrative Measures for the List of Serious Illegal Dishonesty in Market Supervision and Administration”, stop publicizing relevant information and lift corresponding management measures.

If the parties are dissatisfied with this decision, they may apply for administrative reconsideration to the CNIPA within 60 days from the date of receipt of this decision, or file an administrative lawsuit with the People’s Court with jurisdiction within 6 months from the date of receipt of this decision. During the reconsideration and litigation, the above decision shall not be suspended.

Orange Book Listings: Republican Led FTC Picks Up Where Democrat Led FTC Left Off

Key Takeaways

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC), now under Republican leadership, has continued its scrutiny of Orange Book listings for device patents, signaling bipartisan concern over potential anti-competitive practices

Despite new Warning Letters, many of the questioned patents were already delisted or tied to discontinued products, suggesting limited immediate impact on generic competition

Both branded and generic drugmakers may need to reassess litigation strategies and patent listings as regulatory and enforcement dynamics evolve

During the past two years, we have reported on actions regarding the listing of certain patents in the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Orange Book for drug/device products where the patents focus on the device aspect of the product.1 During the Biden Administration, the FTC, under Democratic-led leadership, started taking note of what it deemed to be “improper” Orange Book patent listings. With all of the changes being implemented by the Trump Administration and at FTC, an open question remained as to whether the FTC would remain active in this area. We now have at least a partial answer to this question – the propriety of certain Orange Book patent listings will remain a focus of FTC.

Under the Biden Administration, the FTC issued two sets of Warning Letters (on November 7, 2023, and April 30, 2024) to multiple drug manufacturers and FTC commenced so-called patent listing dispute proceedings before FDA. Historically, however, the FDA has treated the listing of patents as an administrative matter and does not challenge the information submitted by the NDA holder. As we noted on July 17, 2024, those proceedings initiated by FTC had a minimal impact, as many of the patents remained in the Orange Book.

However, on December 20, 2024, the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit held that certain patents that were listed in the Orange Book for an asthma inhaler should have been delisted as the claims in question did not recite the active ingredient. Teva Branded Pharmaceutical Products R&D, Inc. et al. v. Amneal Pharmaceuticals of New York, LLC et al., (Fed. Cir Case 2024-1936, Dec. 20, 2024). On March 3, 2025, the Federal Circuit denied Teva’s petition for an en banc hearing. We have observed that in recent updates to the Orange Book, many device type patents have been delisted, presumably at the NDA holder’s request.

For certain products, the Teva decision could lead to additional patent listing disputes and the potential for antitrust counterclaims where patents focusing on the device aspect of drug/device patents are listed. Determining when this would be a potential strategy for generic companies involves an analysis of the competitive landscape, the timeliness of the FDA’s review, the types of patents the brand holds and what the expiration date is for each patent. But, with the significant changes brought about by the Trump Administration, it was an open question how active the FTC would be going forward, even after the Teva decision.

Specifically, on January 20, 2025, President Trump designated Andrew Ferguson to become the new Chairman of the FTC. Then, on March 18, 2025, President Trump fired the two remaining FTC Democratic Commissioners. All these changes begged the question as to whether a Republican-led FTC would continue to take aim at Orange Book listings? The answer to that question appears to be ‘yes’! On May 21, 2025, the new FTC leadership issued Warning Letters that were similar to the ones sent in 2023 and 2024 to seven companies, questioning the legitimacy of the listings for multiple products. Like the previous Warning Letters, FTC’s action was to institute patent dispute procedures at FDA.

In the May 21, 2025, FTC Press Release, Commissioner Ferguson stated:

The American people voted for transparent, competitive, and fair healthcare markets and President Trump is taking action. The FTC is doing its part, . . . . When firms use improper methods to limit competition in the market, it’s everyday Americans who are harmed by higher prices and less access. The FTC will continue to vigorously pursue firms using practices that harm competition.

We have reviewed each of the seven Warning Letters published by FTC (that cover 16 products) and a deeper dive indicates that Commissioner Ferguson’s proclamation may not have a significant impact on competition. Of the 16 brand products identified, seven have been discontinued by the brand, one of the products already has multiple generic competitors, the patents for two of the products will expire in roughly three months, and, for five others, the products in question have Orange Book listed patents whose legitimacy for listing was not questioned by FTC expiring later than those whose legitimacy was questioned. It appears that only one of the sixteen products appears to only list patents questioned by FTC. Moreover, at the time the FTC’s letters were sent, several of the patents in question had already been delisted from the Orange Book.

We also note that FTC has deferred action to the FDA, which is in the midst of significant staffing reductions that have led to slower response times. And, as discussed above, the FDA has traditionally taken the position that its role in patent listings is only ministerial. That being said, it will be interesting to see whether the new FDA leadership will take a different view.

While the new FTC has continued in its predecessor’s wake by sending out a series of Warning Letters relating to Orange Book patents, whether this action will create a more competitive landscape remains to be seen. And, both branded and generic companies may need to rethink their strategies in dealing with patents whose Orange Book listing is questionable. For example, for those products where there are both FTC questioned and unquestioned patents listed in the Orange Book, both the brand and generic company may desire legal certainty and the inclusion of both types of patents in a single lawsuit may be preferred to separate suits. Even if device patents are ultimately removed from the Orange Book, the possibility of litigation over these patents at some point in time still exists. The industry should certainly pay close attention to future developments in this area.

1] See Chad A. Landmon, Andrew M. Solomon, Federal Circuit Refuses to Rehear Case Involving Orange Book Listing of Device Patents, Polsinelli (Mar. 05, 2024), https://natlawreview.com/article/federal-circuit-refuses-rehear-case-involving-orange-book-listing-device-patents ; Court Ruling Alters the Calculus for Orange Book Patent Listings, Polsinelli (Jan. 23, 2025), https://www.polsinelli.com/publications/court-ruling-alters-the-calculus-for-orange-book-patent-listings; Federal Circuit Decides Case Involving Orange Book Listing of Device Patents, Polsinelli (Dec. 23, 2024), https://natlawreview.com/article/federal-circuit-decides-case-involving-orange-book-listing-device-patents; The FTC’s Challenge to the Listing of Device Patents in the Orange Book: What Challenge?, Polsinelli (Jul. 17, 2024), https://natlawreview.com/article/ftcs-challenge-listing-device-patents-orange-book-what-challenge

No Credit Where It Isn’t Due: The Importance of Preemption and Inventorship in Patent Law

Mr. Storms, an individual with significant experience with Bitcoin mining, is the founder and sole employee of BearBox LLC. Mr. McNamara and Dr. Cline co-founded Lancium in November 2017 with the intention of co-locating flexible datacenters (e.g., Bitcoin miners) at wind centers to exploit the highly variable power output of windfarms.

Lancium intended to exploit the power output of flexible datacenters by “ramping down” and selling power to the electrical grid when energy prices are high. Conversely, when energy prices were low flexible datacenters would “ramp up.” These concepts were disclosed by Lancium in February 2018 in International Publication No. WO 2019/139632, entitled “Method and System for Dynamic Power Delivery to a Flexible Datacenter Using Unutilized Energy Sources.” This application names McNamara and Cline as inventors, and has a priority date of January 2018.

In 2019, Lancium began to develop internally its own software to control cryptocurrency miners, which it monitored at least one windfarm with by May 2019. Lancium also worked with various companies to design and manufacture portable mining containers.

Around this same time (late 2018 to early 2019) BearBox began to design, build, and test the BearBox system that allowed a remote user to control an individual relay to turn on and off Bitcoin miners. By May 7, 2019, Mr. Storms developed source code that could control a mining site based on various economic conditions, such as the cost of electricity.

On May 3, 2019, Mr. Storms met Lancium for cocktails and dinner at a cryptocurrency conference, where Mr. Storms and Mr. McNamara discussed the Bear Box system. The two exchanged numbers, but never met in person again. On May 8, 2019, after a few exchanged text messages, Mr. McNamara asked Mr. Storms for BearBox design specifications. Mr. Storms responded the by an email with the following attachments: (1) a one-page BearBox Product Specification Sheet; (2) an annotated diagram of BearBox’s Automatic Miner Management System; (3) specification sheets on fans and other hardware components; and (4) a data file modeling a simulation of the BearBox system. Mr. McNamara credibly testified that he spent no more than three minutes reviewing the attachments before considering the price of the BearBox system too high compared to other solicited manufacturers.

On October 28, 2019, Lancium filed U.S. Provisional App. No. 62/927,119 ( the ’119 application), which ultimately issued as the ’433 patent, entitled, “Method and Systems for Adjusting Power Consumption Based on a Fixed-Duration Power Option Agreement.” The ’433 patent relates to a set of computing systems that are configured to perform computational operations using power from a power grid; and a control system that monitors a set of conditions and receives power option data based, in part, on a power option agreement, and McNamara and Cline are the named inventors.

BearBox brought a lawsuit against Lancium asserting, inter alia, claims of sole or joint inventorship of the ’433 patent and conversion under Louisiana state law. Lancium succeeded on summary judgment that federal patent law preempted the conversion claim as pled.

Lancium was denied summary judgment on inventorship, but in the interim, the district court struck a supplemental report from BearBox’s technical expert. The district court determined BearBox had acted in bad faith when it served the report three weeks before the start of trial, and five months after the close of expert discovery, without seeking leave of court or Lancium’s consent, as required by the district court’s scheduling order.

Following a three day bench trial, the district court concluded that BearBox had not met its burden under the inventorship claim by clear and convincing evidence. BearBox appealed the district court decision.

Issues

Did the district court err in holding BearBox’s claim for conversion, under Louisiana state law, as pled is preempted by federal patent law?

Did the district court err in deciding to strike BearBox’s expert’s supplemental report in toto?

Did the district court err in holding that BearBox failed to provide clear and convincing evidence that Mr. Storms should be named a sole or joint inventor?

Holding

No, the district court properly held that federal patent law preempted the state law conversion claim as pled by BearBox.

No, the district court properly excluded BearBox’s expert’s supplemental report.

No, the district court properly held that BearBox failed to provide clear and convincing evidence that Mr. Storms should be named a sole or joint inventor.

Reasoning

Preemption of Conversion Claim

The Federal Circuit reviewed de novo the district court’s grant of summary judgment as is required under the law of the regional circuit, the Third Circuit. However, for the question of whether federal patent law preempts a state law claim Federal Circuit law governs.

While there are three types of preemption: explicit, field, or conflict preemption; only conflict preemption was implicated by BearBox’s claim. Conflict preemption occurs “when a state law stands as an obstacle to the accomplishment and execution of the full purposes and objectives of Congress.” BearBox v. Lancium, 2023-1922, 12 (Fed. Cir. 2025) (quoting Ultra-Precision Mfg., Ltd. v. Ford Motor Co., 411 F.3d 1369, 1377 (Fed. Cir. 2005)). While there are several congressional objectives for federal patent law, “public disclosure and use . . . is the centerpiece of federal patent policy.” BearBox, 23-1922 at 12 (quoting Bonito Boats, Inc. v. Thunder Craft Boats, Inc., 489 U.S. 141, 157 (1989)). Thus, any state law that “substantially interferes with the enjoyment of an unpatented utilitarian or design conception which has been freely disclosed by its author to the public” is preempted as contravening the ultimate goal of federal patent law. Id.

Under Louisiana state law, conversion is “an act in derogation of the plaintiff’s possessory rights and any wrongful exercise or assumption of authority over another’s goods, depriving him of the possession, permanently or for an indefinite time.” BearBox, 23-1922 at 13 (quoting Bihm v. Deca Sys., Inc., 226 So. 3d 466, 478 (La. App. 1 Cir. 2017)). A Louisiana conversion cause of action is not necessarily preempted by federal patent law, as a it may cover a range of conduct not implicating federal patent law. Id. at 13. Additionally, BearBox’s claim was not based on acts of patent infringement or a determination of inventorship, but rather on conversion of documents and information. Id. at 13. However, under Federal Circuit law, a preemption analysis is not a “mechanical compar[ison]” of the required elements of the state law claim with the objectives embodied in the federal law. Id. Instead, the analysis is whether the state law as pled “stands as an obstacle to the accomplishment of the full purposes and objectives of Congress.” Id. (quoting Ultra Precision, 411 F.3d at 1378).

Under this analysis the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s determination that BearBox’s conversion claim was preempted by federal patent law. BearBox’s claim, as pled, was “essentially an inventorship cause of action and patent infringement cause of action” that sought patent-like protection for ideas that are unprotected under federal law. BearBox, 23-1922, at 14. The Federal Circuit held the conversion claim “reads like a patent infringement cause of action.” BearBox, 23-1922 at 14. Even the damages sought by BearBox for the use, sale, and monetization of the technology it alleged it owns and invented, were patent-like damages. BearBox’s proposed damages were a “repackaged form of a royalty payment,” instead of the proper measure of damages under a Louisiana conversion claim, which is the return of the property or the value of the property at the time of the conversion. BearBox, 23-1922at 15-16.

Furthermore, federal patent law generally precludes a plaintiff from recovering damages from a defendant’s making, using, offering to sell, or selling an “unpatented discovery after the plaintiff makes the discovery available to the public.” BearBox, 23-1922 at 16 (quoting Ultra-Precision, 411 F.3d at 1380). Here, BearBox’s technology was not patented and was freely shared with others. Thus, allowing BearBox’s claim to proceed would potentially allow it to “recover lost profits or a reasonable royalty from its competitor . . . [for] alleged use of technical information that ‘otherwise remain[s] unprotected as a matter of federal law.’” BearBox, at 16-17 (quoting Bonito Boats, 489 U.S. at 156).

Exclusion of Expert Report

BearBox argued the district court’s decision to strike the supplemental expert report in toto was an abuse of discretion for three reasons: (1) the untimely supplemental report was justified; (2) the supplemental report did not offer new opinions; and (3) the district court incorrectly determined the Pennypack factors weighed in favor of exclusion. BearBox, 23-1922 at 17. The Federal Circuit reviewed the district court’s evidentiary rulings for abuse of discretion.

BearBox first asserted that its expert’s supplemental report, although untimely, was justified because Lancium raised a new claim construction dispute for the first time after the close of discovery. BearBox, 23-1922 at 17-18. The Federal Circuit, however, viewed this assertion as a mischaracterization of the record. While the district adopted Lancium’s construction after the close of discovery, the adopted constructions were raised before and were not new to either BearBox or its expert. The Federal Circuit agreed that BearBox should have addressed Lancium’s proposed constructions in its expert reports.

Next, BearBox asserted that the district court erred in concluding its expert’s report offered new opinions. BearBox, 23-1922 at 19-20. The Federal Circuit saw no error in the determination that the opinions in the Supplemental Report were “beyond mere elaboration or clarification.” Id. at 19. Furthermore, the portions of the prior expert reports BearBox pointed to as support for its claim construction did not overcome or otherwise rectify its expert’s “clearly contradictory testimony.” Id.

Lastly, the Federal Circuit took up BearBox’s contention that even if the supplemental report contained new opinions, striking the report was an “extreme sanction, not normally warranted absent a showing of willful deception or flagrant disregard of court orders.” BearBox, 23-1922 at 20 (internal citations omitted). The Federal Circuit reviewed the district court’s Pennypack factor analysis forabuse of discretion in excluding the evidence. BearBox, 23-1922 at 20-21. The Pennypack factors are:

(1) “the prejudice or surprise in fact of the party against whom the excluded witnesses would have testified” or the excluded evidence would have been offered; (2) “the ability of that party to cure the prejudice”; (3) the extent to which allowing such witnesses or evidence would “disrupt the orderly and efficient trial of the case or of other cases in the court”; (4) any “bad faith or willfulness in failing to comply with the court’s order”; and (5) the importance of the excluded evidence.

BearBox, 23-1922 at 20-21 (quoting ZF Meritor, 696 F.3d at 298 (quoting Meyers v. Pennypack Woods Home Ownership Assn., 559 F.2d 894, 904–05 (3d Cir. 1977))).

For factors (1) and (2), the Federal Circuit reiterated that “the supplemental report offered new legal theories and opinions related to BearBox’s alleged conception and communication of the subject matter of the ’433 patent.” BearBox, 23-1922 at 21. Additionally, the new theories, if allowed, would have unfairly prejudiced Lancium because it was months after the close of discovery and only a few weeks before trial. While allowing Lancium’s expert to respondcould have cured some of the prejudice, given the strained schedule and quickly approaching trial, the Federal Circuit agreed that Lancium had “no meaningful opportunity” to sufficiently cure the prejudice. Id.

Similarly, for factor (3), the Federal Circuit saw no error in the conclusion that the risk of prejudice to Lancium was uncurable in light of the strained schedule and quickly approaching trial, and BearBox presented no evidence to demonstrate that the district court’s determination for this factor was erroneous. Id. at 22.

For factor (4), the Federal Circuit pointed to the district court’s scheduling order that stated that “after discovery no other expert reports [would] be permitted without either the consent of all parties or leave of the court.” BearBox, 23-1922 at 22. Since BearBox did not seek either Lancium’s consent or leave from the district court, the Federal Circuit saw no error in the determination that BearBox’s disregard of the scheduling order indicated bad faith and weighed in favor of exclusion of the report. Id.

For factor (5), the Federal Circuit reviewed the district court’s analysis, which it noted was assessed in two different ways. See BearBox, 23-1922 at 22-23. First, the district court compared BearBox’s expert opening and reply reports to the supplemental report at issue, and concluded the supplemental report “went beyond mere elaboration or clarification.” Id. at 22. Alternatively, the district court assumed the supplemental report did not contain new opinions. Id. at 23. Nevertheless, the district court found it could not reasonably conclude that the exclusion of the supplemental report would harm BearBox. Id. Thus, under either analysis the Federal Circuit viewed the district court as doubtful of the supplemental report’s importance and saw no error in either analysis.

The Federal Circuit ultimately determined, noting the considerable discretion of district courts in expert discovery and case management matters, that there was no abuse of discretion in excluding BearBox’s supplemental report.

Inventorship

For inventorship, BearBox did not challenge the district court’s factual findings or credibility determinations, rather it contended that the district court erred by: (1) excluding Mr. Storms’ testimony as hearsay; (2) analyzing individual claim elements (rather than a combination) by comparing them to Mr. Storms’ corroborating documents; and (3) applying the rule of reason by evaluating documents in isolation.

A district court may correct inventorship under 35 U.S.C. § 256 when it determines that an inventor has been erroneously omitted from a patent. BearBox, 23-1922 at 24. Inventorship is determined on a claim-by-claim basis and the issuance of a patent creates a presumption that the named inventors are the true and only inventors. Id. Any party seeking to correct inventorship of a patent must show by clear and convincing evidence that a joint inventor “contributed significantly to the conception . . . or reduction to practice of at least one claim,” and the “contribution” must arise out of some joint behavior of the inventors. Id. at 25 (internal citations omitted). Furthermore, an alleged joint inventor’s testimony is insufficient to establish inventorship and must be corroborated by further evidence. Id.

To determine whether an alleged co-inventor’s testimony has been sufficiently corroborated a rule of reason is applied by the district court. BearBox, 23-1922 at 24 (quoting Blue Gentian, LLC v. Tristar Prod., Inc., 70 F.4th 1351, 1357 (Fed. Cir. 2023)). The rule of reason requires the district court to examine all pertinent evidence to “determine whether the inventor’s [testimony] is credible.” BearBox, 23-1922 at 24 (quoting Blue Gentian, 70 F.4th at 1358). Since inventorship is a question of law based on underlying facts, a district court’s inventorship determination is reviewed de novo and the underlying fact findings are reviewed for clear error. BearBox, 23-1922 at 24-25 (citing In re VerHoef, 888 F.3d 1362, 1365 (Fed. Cir. 2018); and Dana-Farber Cancer Inst., 964 F.3d at 1370 (Fed. Cir. 2020)).

With respect to the ’433 patent, the only information shared by Mr. Storms with Lancium was his May 2019 email containing the four attachments, which the district court held were insufficient to establish that Mr. Storms’ inventorship. As a result, the Federal Circuit affirmed that BearBox had failed to prove by clear and convincing evidence that Mr. Storms had either conceived of, or communicated prior to Lancium’s independent conception, the subject matter of any claim of the ’433. BearBox, 23-1922 at 25.

BearBox also contended that the district court improperly excluded, as hearsay, Mr. Storms’ testimony about statements he made to Mr. McNamara at the May 2019 dinner. The Federal Circuit acknowledged some merit in BearBox’s contention but held that BearBox did not properly preserve its claim of error for appellate review. BearBox, 23-1922 at 27. Specifically, when the district court ruled that Mr. Storms’ testimony was hearsay, BearBox’s counsel made no offer of proof as to what Mr. Storm’s response would have been had he been permitted to answer the question. Id. Therefore, the Federal Circuit could not determine that there was prejudicial error in excluding Mr. Storms’ testimony as hearsay. Id.

BearBox’s next contention was that the district court failed to consider claim elements in combination and only focused on individual elements when it evaluated whether Storms conceived of the claimed inventions. BearBox, 23-1922 at 27-28. The only case BearBox cited in support of this argument that addressed inventorship was Blue Gentian. Id. The Federal Circuit, however, noted that in Blue Gentian it did not adopt a general criticism of limitation-by-limitation analysis. Id. Thus, Blue Gentian could not support a determination that the district court erred in adopting a limitation-by-limitation approach.

Lastly, BearBox contended that the district court erred by “referenc[ing] the Rule of Reason” but “not address[ing] whether, under the Rule of Reason, the totality of the evidence, including circumstantial evidence supports the credibility of the inventors’ story.” BearBox, 23-1922 at 28 (internal quotations omitted). BearBox asserted that two of the district court’s fact findings were inconsistent, and thus, improperly evaluated. First was the finding that “through late 2018 into early 2019, Storms began to design, build, and test a system . . . that allowed a remote user to control individual relays so that miners could be turned on or off.” Id. The alleged conflicting finding was “BearBox did not otherwise proffer evidence establishing that the BearBox System could individually control the system of 272 miners.” Id. The Federal Circuit held the that the later fact finding was taken out of context. For that finding of fact, the district court found, based on a credibility determination regarding competing expert testimony, that Mr. Storms’ “Source Code ‘only ever instructs . . . all the relays of the PDUs to turn on or off.” Id. at 29 (emphasis added). Additionally, the district court found, which BearBox did not mention on appeal, that “even if Storms’ Email did meet [the claim element at issue] of the ’433 patent, the Court finds as a matter of fact that Storms did not communicate [this element] prior to [Lancium’s] independent conception.” BearBox, 23-1922 at 29. Finding the remaining arguments unpersuasive, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s dismissal of the state law conversion claim, exclusion of the supplemental expert report, and denial of the claim that Mr. Storms was either a sole or joint inventor of the ’433 patent.

Listen to this post

Take That Conception Out of the Oven – It’s CRISPR Even If the Cook Doesn’t Know

Addressing the distinction between conception and reduction to practice and the requirement for written description in the unpredictable arts, the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit explained that proof of conception of an invention does not require that the inventor appreciated the invention at the time of conception. Knowledge that an invention is successful is only part of the case for reduction to practice. Regents of the Univ. of Cal. et al. v. Broad Inst. et al., Case No. 22-1594 (Fed. Cir. May 12, 2025) (Reyna, Hughes, Cunningham, JJ.)

The Regents of the University of California, the University of Vienna, and Emmanuelle Charpentier (collectively, Regents) and the Broad Institute, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the President and Fellows of Harvard College (collectively, Broad) were each separately involved in research concerning CRISPR systems that “are immune defense systems in prokaryotic cells that naturally edit DNA.” At issue was the invention of the use of CRISPR systems to modify the DNA in eukaryotic cells. Regents and Broad filed competing patent applications resulting in an interference proceeding under pre-AIA law at the US Patent & Trademark Office Board of Patent Appeals & Interferences to determine which applicant had priority to the invention.

The main issue before the Board was a priority dispute over who first conceived of the invention and sufficiently reduced it to practice under pre-AIA patent law. Regents submitted three provisional patent applications dated May 2012, October 2012, and January 2013 and moved to be accorded the benefit of the earliest filing date, May 2012, for the purpose of determining priority. Alternatively, Reagents sought to be accorded either October 2012 or January 2013 as its priority date. The Board found that Regents’ first and second provisional applications (filed in May and October 2012, respectively) were not a constructive reduction to practice because neither satisfied the written description requirement of 35 U.S.C. § 112. The third provisional application, filed in January 2013, was the first to amount to a constructive reduction to practice of the counts in interference. The Board then ruled that Broad was the senior party for the purposes of priority in the interference proceeding because Broad reduced the invention to practice by October 5, 2012, when a scientist submitted a manuscript to a journal publisher. The Board ruled that Regents failed to prove conception of the invention prior to Broad’s actual reduction to practice. Regents appealed.

Regents argued that in assessing conception, the Board “legally erred by requiring Regents’ scientist to know that their invention would work.” The Federal Circuit agreed and vacated the Board’s decision. As the Court explained, there are three stages to the inventive process: conception, reasonable diligence, and reduction to practice. At the conception stage, “an inventor need not know that his invention will work for conception to be complete.” Rather, knowledge that the invention will work, “necessarily, can rest only on an actual reduction to practice.” The Board therefore legally erred by requiring Regents to know its invention would work to prove conception.

The Court found that the Board should have considered whether a person of ordinary skill in the art could have reduced the conception to practice using only routine skill or routine techniques “without extensive research or experimentation.”

Evidence of purported experimental success by others (at the time of the conception), and the use of routine methods in subsequent successful experiments are pertinent to the inquiry. Here the Board erred by focusing on the difficulties Regents’ inventors encountered and their doubts of success rather than on “routine methods or skill.” The Federal Circuit noted that a complete conception does not occur if “a research plan requires extensive research before the inventor can have a reasonable expectation that the limitations of the count will actually be met.” That issue should be determined by considering “the reasonable expectation of a person of ordinary skill in the art” and whether that person would “have been able to reasonably predict” that experimentation would produce the claimed result. On remand, the Court instructed the Board to evaluate whether the later party to reduce to practice was the first to conceive of the invention and subsequently exercised reasonable diligence in reducing the invention to practice, or whether it was the first to conceive of the invention that then communicated the conception to the adverse claimant.

Regent also argued that the Board legally erred in its written description analysis by requiring the first provisional application “to convince a person of ordinary skill in the art that the invention will work in eukaryotes.” The Federal Circuit disagreed because the written description requirement mandates that a patent’s disclosure “must clearly recognize that the inventor invented what is claimed.” The test requires a court to “determine how a person of ordinary skill in the art would understand the four corners of the specification.” The Board correctly analyzed whether a person of ordinary skill in the art would understand that Regents had possession of the claimed subject matter considering the “highly unpredictable and complex” subject matter.

Copyright, AI, and Politics

In early 2023, the US Copyright Office (CO) initiated an examination of copyright law and policy issues raised by artificial intelligence (AI), including the scope of copyright in AI-generated works and the use of copyrighted materials in AI training. Since then, the CO has issued the first two installments of a three-part report: part one on digital replicas, and part two on copyrightability.

On May 9, 2025, the CO released a pre-publication version of the third and final part of its report on Generative AI (GenAI) training. The report addresses stakeholder concerns and offers the CO’s interpretation of copyright’s fair use doctrine in the context of GenAI.

GenAI training involves using algorithms to train models on large datasets to generate new content. This process allows models to learn patterns and structures from existing data and then create new text, images, audio, or other forms of content. The use of copyrighted materials to train GenAI models raises complex copyright issues, particularly issues arising under the “fair use” doctrine. The key question is whether using copyrighted works to train AI without explicit permission from the rights holders is fair use and therefore not an infringement or whether such use violates copyright.

The 107-page report provides a thorough technical and legal overview and takes a carefully calculated approach responding to the legal issues underlying fair use in GenAI. The report suggests that each case is context specific and requires a thorough evaluation of the four factors outlined in Section 107 of the Copyright Act:

The purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes

The nature of the copyrighted work

The amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole

The effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

With regard to the first factor, the report concludes that GenAI training run on large diverse datasets “will often be transformative.” However, the use of copyright-protected materials for AI model training alone is insufficient to justify fair use. The report states that “transformativeness is a matter of degree of the model and how it is deployed.”

The report notes that training a model is most transformative where “the purpose is to deploy it for research, or in a closed system that constrains it to a non-substitutive task,” as opposed to instances where the AI output closely tracks the creative intent of the input (e.g., generating art, music, or writing in a similar style or substance to the original source materials).

As to the second factor (commercial nature of the use), the report notes that a GenAI model is often the product of efforts undertaken by distinct and multiple actors, some of which are commercial entities and some of which are not, and that it is typically difficult to discern attribution and definitively determine that a model is the product of a commercial or a noncommercial actor.

Even if an entity is for-profit, that does not necessarily mean the modeling use will be considered “commercial.” The work of researchers developing a model for purposes of publishing an academic research paper, for example, would not be deemed commercial. Similarly, a nonprofit could very well develop a GenAI model to license for commercial purposes.

With regard to the third factor (the amount of the copyrighted work used), the report acknowledges that machine learning processes often require ingestion of entire works and notes that the wholesale taking of entire works “ordinarily weighs against fair use.” However, in evaluating the use of entire works in GenAI models, the report offers two questions for analysis:

Is there a transformative purpose?

How much of the work is made publicly available?

Fair use is much more likely in instances where a GenAI model employs methods to prevent infringing outputs.

Finally, addressing the fourth factor (market harm), the report acknowledges that the analysis of fair use in GenAI training places the CO in “uncharted territory.” However, the CO suggests that assessment of market harm should address broad market “effects” and not merely the market harm for a specific copyrighted work. The report explains that the potential for AI-generated outputs to displace, dilute, and erode the markets for copyrighted works should be considered because such effects are likely to result in “fewer human-authored” works being sold. This reflects concerns raised by artists, musicians, authors, and publishers about declining demand for original works as AI-generated imitations proliferate. Where GenAI systems compete with or diminish licensing opportunities for original human creators – especially in fields such as illustration, voice acting, or journalism – the fourth factor is likely to weigh strongly against fair use.

Practice Note: Companies developing GenAI systems for text, image, music, or video generation should proceed cautiously when incorporating copyrighted material into training datasets. The CO report casts doubt on assumptions that current training practices are broadly protected under fair use. GenAI developers should consider initiatives such as proactively licensing the content used to train their models. As this fair use issue remains an evolving area of copyright law, companies should be prepared to adjust business models in response to judicial or legislative developments.

On May 10, 2025, the day after the report issued, the White House terminated Registrar of Copyright Shira Perlmutter “effective immediately.” On May 12, 2025, the White House appointed Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche, who represented Donald Trump during his 2024 criminal trial, as acting registrar. The CO has raised questions about the appointment on the basis that only Congress has the power to fire the registrar or appoint a new one.

Federal Circuit Addresses District Court Oversight of Expert Testimony on Infringement

In Steuben Foods Inc. v. Shibuya Hoppmann Corporation, the Federal Circuit addressed the boundaries a district court may impose on experts by deeming their testimony wrong as a matter of law.

Background

Steuben Foods Inc. (“Steuben”) owns U.S. Patent Nos. 6,209,591 (the “’591 Patent”), 6,536,188 (the “’188 Patent”), and 6,702,985 (the “’985 Patent”), collectively (the “Asserted Patents”)). All of the Asserted Patents related to systems for the aseptic packaging of food products.

Starting in 2010, Steuben filed suit against Shibuya Hoppmann Corp., Shibuya Kogyo Co. Ltd., and HP Hood LLC (collectively, “Shibuya”) for allegedly infringing the Asserted Patents. In 2019, the actions were consolidated and transferred to the District of Delaware.

The district court issued its claim construction order in 2020 and denied cross-motions for summary judgment of noninfringement, infringement, and invalidity in 2021. Prior to trial, the district court denied Shibuya’s motion for JMOL of noninfringement under FRCP 50(a) as to each of the Asserted Patents. Then, after a five-day jury trial the jury returned a verdict in favor of Steuben, finding that Shibuya infringed the Asserted Patents and that the Asserted Patents were not invalid. The jury awarded Steuben over $38 million in damages.

Following trial, Shibuya renewed its motions for JMOL of noninfringement under FRCP 50(b) and moved for JMOL with respect to invalidity and damages. Shibuya also moved for a new trial on noninfringement, invalidity, and damages.

With respect to Steuben’s infringement case, the district court determined that Steuben’s expert, Dr. Sharon, was wrong as a matter of law for each of the Asserted Patents. For the ’591 Patent, the district court found that Dr. Sharon’s testimony was inconsistent with the specification of the ’591 Patent. For the ’188 Patent, the district court found Dr. Sharon’s testimony could not have convinced a reasonable juror that accused devices were substantially similar to the claimed invention. For the ’985 Patent, the district court found Dr. Sharon’s testimony to be contrary to one of the parties’ stipulated constructions. Ultimately, and notwithstanding the jury’s verdict to the contrary, the district court granted Shibuya’s motion for JMOL of noninfringement for all Asserted Patents.

The district court also preemptively granted a new trial under FRCP 50(c)(1) in the event that its JMOLs with respect to noninfringement, invalidity, or damages were reversed or vacated. The district court entered an FRCP 54(b) judgment in favor of Shibuya, and Steuben appealed.

Issues

Did the district court err in discrediting Steuben’s expert testimony, and in consequentially granting Shibuya’s motion for JMOL of noninfringement of the ’591 and ’118 Patents?

Did the district court err in discrediting Steuben’s expert testimony, and in consequentially granting Shibuya’s motion for JMOL of noninfringement of the ’118 Patent?

Reasoning and Outcome

1. The Federal Circuit held that the district court erred in discrediting Steuben’s expert testimony, and in consequentially granting Shibuya’s motion for JMOL of noninfringement of the ’591 and ’118 Patents.

The specification of the ’591 patent described a valve wherein a secondary sterile region (purple in Fig. 1 below) is supplied with a sterilizing media (item 424 in Fig. 1 below), such that a portion of the valve stem (red in Fig. 1 below) is sterilized when the valve stem leaves the primary sterile region (blue in Fig. 1 below):

Figure 1: An illustration of the invention described in Steuben’s ’591 Patent

The relevant limitation of the claim at issue read “a second sterile region positioned proximate said first sterile region.” Notably, the supplied sterilizing media was described in the specification of the ’591 Patent, but was not recited in the claim at issue.

Steuben’s theory of infringement was that Shibuya’s accused product (illustrated in Fig. 2 below) contained a first sterile region in the form of a sterile fill pipe (tan in Fig. 2 below) which was proximately positioned from a surrounding second sterile region (blue in Fig. 2 below):

Figure 2: An illustration of the invention described in Shibuya’s accused product

The district court structured its analysis with respect to infringement of the ’591 Patent based on the RDOE. The Federal Circuit recited the relevant case law on RDOE:

An alleged infringer may avoid a judgment of infringement by showing the accused “product has been so far changed in principle [from the asserted claims] that it performs the same or similar function in a substantially different way.” SRI Int’l v. Matsushita Elec. Corp. of Am., 775 F.2d 1107, 1124 (Fed. Cir. 1985). A patentee alleging infringement bears the initial burden of proving infringement. Id. at 1123. If the patentee establishes literal infringement, then an accused infringer claiming noninfringement under RDOE bears the burden of establishing a prima facie case of noninfringement under RDOE. Id. at 1123–24. If the accused infringer meets this burden, then the burden shifts back to the patentee to rebut the prima facie case. Id. at 1124.

Shibuya’s expert, Dr. Glancey, testified that the principle of operation of the invention of the ’591 Patent was the supply of a sterilizing media to actively maintain the second sterile region. Because Shibuya’s accused product had no such supplied sterilizing media, the district court determined that Dr. Glancey’s testimony satisfied Shibuya’s burden to raise a prima facie RDOE defense.

In rebuttal, Steuben’s expert, Dr. Sharon, testified that the principle of operation of the invention was “…having these two sterile regions that the valve is sort of constrained to so that as it opens and closes, it only stays within those two regions and it does not go into any non-sterile region [….]” Although the jury apparently accepted Dr. Sharon’s version with regard to the principle of operation, the district court found Dr. Sharon’s testimony contrary to the specification of the ’591 Patent and entitled to no weight. As a consequence, the district court granted JMOL because Steuben had failed to rebut Shibuya’s prima facie RDOE defense in the eyes of a reasonable juror.

In reversing the district court, the Federal Circuit found that Dr. Sharon’s testimony regarding the principle of operation of the ’591 Patent’s invention constituted substantial evidence for the jury’s rejection of Shibuya’s RDOE defense. Thus, the district court erred by discrediting Dr. Sharon’s rebuttal testimony regarding Shibuya’s RDOE defense, and in granting JMOL of noninfringement of the ’591 Patent.

With respect to the ’118 Patent, Dr. Sharon again testified, this time regarding the substantial equivalents of elements defined via mean-plus-function language. Dr. Sharon testified that Shibuya’s accused neck grippers and rotary wheels operate in substantially the same way as the conveyors and conveyor plates defined in the ’118 Patent’s specification. Shibuya’s expert, Dr. Glancey, testified that there were several differences between the accused rotary systems and the claimed conveyor systems.

The district court granted JMOL of noninfringement, finding that Dr. Sharon’s testimony was wrong as a matter of law and entitled to no weight. Like with Dr. Sharon’s testimony on Shibuya’s RDOE defense, the district court believed no reasonable juror could credit Dr. Sharon’s testimony that neck grippers and rotary wheels operate in substantially the same way as conveyors and conveyor plates.

According to Federal Circuit precedent on means-plus-function language, “the individual components, if any, of an overall structure that corresponds to the claimed function are not claim limitations. Rather, the claim limitation is the overall structure corresponding to the claimed function.” Odetics, Inc. v. Storage Tech. Corp., 185 F.3d 1259,1268. In the eyes of the Federal Circuit, the district court focused too much on the individual components and failed to consider infringement in the context of the claimed function, for which Dr. Sharon’s testimony constituted substantial evidence.

The Federal Circuit reversed the district court’s grant of JMOL of noninfringement and reinstated the jury’s verdict of infringement with respect to both the ’118 and ’591 Patents.

2. The Federal Circuit held that the district court did not err in discrediting Steuben’s expert testimony, and in consequentially granting Shibuya’s motion for JMOL of noninfringement of the ’985 Patent.

The ’985 Patent included a limitation wherein “atomized sterilant is intermittently added to said conduit[.]” Steuben and Shibuya had stipulated to a construction of “intermittently added” as “[a]dded in a non-continuous matter.” It was also undisputed that Shibuya’s accused machines added sterilant in a continuous matter.

Steuben’s expert, Dr. Sharon, testified that the accused product’s continuous sterilization was substantially equivalent to the “intermittently added” limitation under the Doctrine of Equivalents (the “DOE”) because “…in the end, the point is to get the right amount of sterilant into the bottle.” The district court determined that the “intermittently added” limitation could not be met under the DOE by a continuous addition of sterilant because “intermittently” and “continuously” are antonyms of each other. Consequently, the district court deemed Dr. Sharon’s testimony wrong as a matter of law and granted JMOL of noninfringement of the ’985 Patent.

According to Federal Circuit precedent, DOE may not apply where “the accused device contain[s] the antithesis of the claimed structure,” such that the claim limitation would be vitiated. Deere & Co. v. Bush Hog, LLC, 703 F.3d 1349, 1356 (Fed. Cir. 2012). The Federal Circuit found no error with the district court’s reasoning because finding infringement under DOE where the parties had stipulated to a construction antithetical to the operation of the accused device would vitiate the claim limitation.

The Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s grant of JMOL of noninfringement with respect to the ’985 Patent.

Listen to this post

Considerations for Life Sciences Employers When Planning Reductions in Force

Life sciences employers have been impacted by various market forces in the last several years, and the recent economic turbulence is only adding to the challenges they face.

Many employers in this space have implemented, or are considering, reductions in force (RIFs) to meet these headwinds. Indeed, one industry source cataloged 187 layoffs among biotech companies in 2024—a 57 percent jump compared to 119 layoffs in 2022. That trend appeared to accelerate in the first quarter of 2025, as that same industry source tallied sixty-seven layoffs. A leading consulting firm noted that 30 percent of life sciences senior executives surveyed would focus on cost-cutting initiatives in 2025, including layoffs.

Life sciences employers planning RIFs may want to develop a planning matrix that addresses key employment law compliance issues, as well as considerations that are specific to the industry. This article provides an overview.

Quick Hits

Life sciences employers planning RIFs may want to develop a planning matrix that addresses key employment law compliance issues, including federal and state WARN Act requirements and industry-specific considerations.

Employers may want to ensure they have created defensible and analytical selection criteria for layoffs, ensuring decisions are based on legitimate, nondiscriminatory business justifications and supported by credible evidence.

Conducting a statistical review of preliminary layoff decisions can help employers identify and address any potential disparate impact on certain demographic groups.

1. Consideration of WARN Act and Mini-WARN Requirements

Any reduction in force should take into account federal and state laws that regulate layoffs. The federal Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification (WARN) Act requires employers to provide employees sixty days’ advance notice prior to a “plant closing” or “mass layoff.” A plant closing or mass layoff can be triggered with as few as fifty employment losses at a “single site of employment.”

Moreover, many states have similar plant-closing laws as well, often referred to as “mini-WARN” laws. Some of these laws are not mandatory but rather encourage voluntary compliance, while others contain requirements that, for the most part, follow the federal WARN Act requirements. However, several states’ mini-WARN laws have lower thresholds for employment losses and thus are triggered more easily than the federal WARN Act. These include Maryland (fifteen employees) and Illinois, Iowa, and Wisconsin (twenty-five employees). The Maine law can require severance in certain situations, while California’s law varies from the WARN Act in several ways. New Jersey law requires ninety days’ notice, and, in some cases, the payment of severance. Thus, before conducting the RIF planning process, employers may want to take into account the impact federal WARN Act and state mini-WARN laws may have on the reduction in force well in advance.

2. Developing Defensible Selection Criteria

To defend its layoff decisions, an employer will want to be able to identify legitimate and nondiscriminatory business justifications, backed by credible evidence, as the basis for its RIF employee selections and terminations.

Position or Group Elimination. In some cases, the reason for a decision is easily established, and there is little basis for second-guessing any “selections,” as all of the employees in a specific position or group are terminated. For example, a biotech company might eliminate all research positions working on a particular oncology molecule if early clinical stage results are poor. This type of elimination is the easiest to defend, as all employees are usually affected and there is no basis for an employee to argue he or she was treated unfairly or differently than employees in other demographic categories. Thus, defending selection decisions for these reasons primarily requires explaining and documenting the business rationale for position or group eliminations.

Selections Among Employees in Like Jobs. Employers often will select some but not all employees in a specific position or job classification (for example, a reduction in force affecting 10 percent of employees holding the role “Research Scientist I”). Because the employer is picking and choosing between employees, keeping some and discharging others, the decision can be subject to challenge by employees who believe an impermissible factor may have driven the decision (i.e., age, race, gender, etc.). As such, employers may want to consider utilizing business-based criteria to guide the decision-making. The factors considered can include subjective and objective factors. Factors an employer might utilize include performance, skill sets, tenure, location, or other criteria important to the department involved. (Note that the criteria need not be the same for each group or department.) For example, human resources likely values different skills and proficiencies as compared to product development. Many employers will weigh each factor in a matrix that produces an overall “score” for each employee and then “stack rank” each employee from highest- to lowest-ranked, and ultimately choose the lowest-ranked employees for layoff. By creating such a (relatively) scientific process, the employer will have created valuable evidence of a fair and nondiscriminatory method for its decision-making. While the initial decisions might wisely be considered attorney-client privileged, subject to review by employment counsel, in the event of a charge of discrimination or demand, the employer often benefits from maintaining final documents in a discoverable and nonprivileged format that can be shown (if needed) to employees and their counsel. These documents often form the basis for the company’s defense—proof of the legitimate and nondiscriminatory reasons for the selection.

3. Statistical Review