Growth Management: Moving Small to Mid-Sized Law Firms Out of Start-Up

The business life cycle of a small/mid-sized law firm is often significantly different from the life cycle of other industries. Product companies, for example, have a life cycle that depends on the sustainability of their existing market offerings combined with their ability to innovate and create new offerings. These companies can make long-term strategic investments, change management and, if necessary, completely remake themselves.

Conversely, most small and mid-sized law firms are tied to their equity members’ ability to practice law, originate revenues, and adapt to legal industry developments. These firms usually have little flexibility in dealing with abrupt market changes, poor management or long-term strategic plans.

Because small and mid-sized law firms are owner-operated businesses and rely on equity partners or members to generate revenue, there isn’t time for them to develop systems or pursue long-term priorities. Rarely is there a person, much less a team, whose only responsibility is managing the development of the firm.

Equity partners have little interest in investing in future initiatives that involve short-term risk and deferred profits. A 5-year aggressive growth plan is not attractive to a 60-year-old member at the top of her earnings capacity who needs her current income to max out retirement savings.

Moreover, there is no market in the United States for outside capital investment in law firms (investors seeking financial returns only). The ABA currently does not approve of any models of law firm ownership by non-lawyers. And since most young lawyers do not have the net worth to underwrite long-term strategies that may or may not pay off, senior partner net worth is a vital component of the long-term plans of small and mid-sized law firms.

For these reasons, it is easy to see why small and mid-sized law firms fixate on current profits to the detriment of longer-term goals. Rather than invest in the future, they apply all earnings to partner compensation.

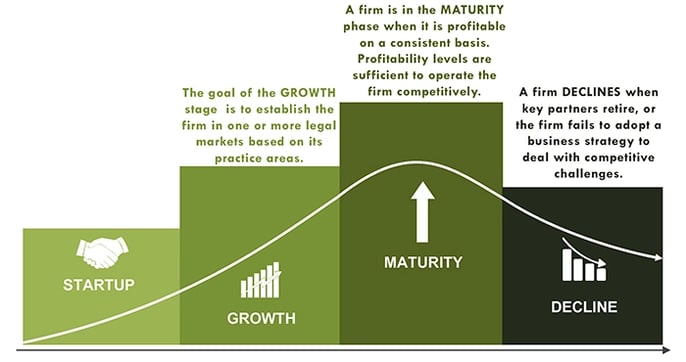

While it may be surprising that small and mid-sized law firms progress at all, most firms do follow a path resembling a business life cycle. When PerformLaw works with law firms that wish to develop into better organizations, we start with the following outline to assess their position on the business life cycle and to guide our recommendations:

To firmly establish the firm in the legal market requires a growth management plan including the following components:

A Focused Start Managing Growth

As with any new company’s start-up, a law firm’s founding partner(s) should first define a vision (long-term future goal), a mission (present business approach to realize the vision), as well as initial financial and strategic objectives (to be revised over the cause of the firm’s existence).

Financial objectives focus on targeted revenues, costs, profit margins, etc. Strategic objectives are long-term competitive positioning goals. Among others, these could include market share, technological leadership, brand name value, and client satisfaction. After giving the firm its purpose, defining the law firm operational strategy is next.

This step should include the following basic elements:

Business Plan

Financial Plan

Entity Creation

Operating Agreement

Office & IT Infrastructure

Software and Apps

Website Development

Compensation and benefit planning

Since the need to generate revenue and positive cash flow is primary, some of these elements remain a work in progress after startup. Beyond billing and collections, high-level business administration develops at a slower pace and requires additional skills. Advanced skill set either come from new hires or outside resources.

Once profits occur on a consistent basis, a growth phase typically starts and requires the firm to move to a professional business management approach, which is less reliant on the firm’s equity members.

Scale and Manage Sustainable Growth

To scale and manage growth successfully, we recommend that law firms determine their projected income versus the projected expenses required to pursue their objectives. Additionally, firms should require members to consider what investments are needed to sustain and grow their revenues and profits.

These investments include operational and marketing components.

Operational investments include:

Staffing mix,

Infrastructure investments,

Practice tools, and

Systems.

Meeting these needs using a combination of in-house resources, outsourced services, and software applications is recommended.

All marketing investments include all components of a law firm’s marketing plan, which are listed and displayed in the graphic below:

Marketing Strategy

Budget & Activity Plan

Contact Management

Metrics

We recommend the same approach to meet the firm’s marketing needs: a combination of in-house resources, outsourced services, and software applications.

This basic planning process and related investments should result in two major benefits:

An operational team with clear legal and non-legal functions and responsibilities

Brand awareness and service differentiation, resulting in a competitive advantage.

Regardless of how a firm chooses to manage a growth phase, we highly recommend these steps to ensure sustainable organizational growth. Using this recommended approach promotes the firm’s brand, supports a healthy cost structure, and promotes the long-term stability of the law firm.

P R E S E N T A T I O N

Here is a helpful presentation that walks you through the various steps of a law firm’s growth and development – from a start-up firm to a firm that exhibits sustainable growth.

Click on the image or presentation link below to view the slides. A link to a video of us explaining each of the slides can be found on Slide 2:

Or click here to view and download the “Moving the Small and Mid-Sized Law Firm Out of Start-Up” presentation.

How Artificial Intelligence Is Re-Shaping Litigation

Imagine sitting in court, getting ready to hear a victim impact statement during a sentencing hearing, but instead of hearing a family member deliver the impact statement about the decedent, you see a video. Not just any video, but an AI generated video of the deceased themselves. A video where the victim has been brought back to life to deliver an emotional impact statement. This is no longer a scenario from a sci-fi movie or from imagination.

This is where litigation and trials are now. The use of AI is rapidly embedding itself into the legal process, and shows no signs of stopping. Recently in Arizona, Stacey Wales created an AI video of her brother, who was tragically killed in a road rage accident, delivering his victim impact statement at his killer’s sentencing hearing. While this was a creative, and rather harmless use of AI in the legal, there have been more sinister uses of AI in the courtroom. Jerome Dewald, representing himself in an employment dispute in front of the New York State Supreme Court Appellate Division’s First Judicial Department, used an AI generated “attorney” to deliver his oral arguments. Justice Sallie Manzanet-Daniels almost immediately halted the presentation when it dawned on her that the person on the screen was not real.

While those are the two newsworthy moments of AI use in the courtroom in 2025, it is a guarantee that more are to come. Additionally, while these two incidents were done by non-attorneys, if this pattern continues, there is no doubt it will start becoming the norm for attorneys to use AI in similar manners.

As of now, outdated guidelines exist for the use of AI in the courtroom; these two incidents in 2025 alone are sufficient to demonstrate why we need stronger, more robust universal rules regarding the use of AI in the litigation process. Furthermore, a large number of the rules revolve around the disclosure of the use of AI, not the use of AI itself. Since the Federal District Court for the Northern District of Texas, namely Judge Brantley Starr, issued a standing order regarding AI disclosures in 2023, several other district courts have followed suit. However, a majority of these standing orders were drafted with the idea of preventing AI hallucinations in court filings and motions. Now in 2025, hallucinations have decreased, making it necessary to create a universal approach and guideline to how we approach AI use in the litigation process.

The Path & The Practice Podcast Episode 125: Kimberly Klinsport, Partner [Podcast]

This episode of The Path & The Practice features a conversation with Kimberly Klinsport, a litigation partner in Foley’s Los Angeles office where she is also the Office Managing Partner. In this discussion, she reflects on growing-up in Palos Verdes, California, attending the University of Southern California for undergrad and earning her J.D. from Loyola Law School. She explains her decision to join Foley as a lateral associate and the various leadership roles she’s held since joining the firm. Kim also gives great advice to law students on how to navigate the evolving entry-level interview process. Finally, Kim provides wonderful insight on the importance of building and maintaining relationships.

Kim’s Profile:

Law School: Loyola Law School

Title: Partner

Foley Office: Los Angeles

Practice Area: Litigation

Hometown: Palos Verdes, CA

College: University of Southern California

Why Governance — Not Growth — Will Define the Next Era of Family Offices

Family Offices are entering a new era — one defined less by asset growth and more by structure, resilience, and governance.

As Forbes recently forecasted, the defining trend for Family Offices in 2025 is not asset growth — it’s professionalization and governance.1 As families confront generational transitions and operational complexity, building resilient governance structures is becoming a strategic imperative, not a secondary concern.

Introducing the Governance Imperative

This shift is further underscored in Deloitte’s recently published 2025 Family Office case study series, The Fireside.[2] The report pulls back the curtain on the often-private world of global Family Offices and reveals an urgent pattern: where governance falters, legacy cracks. Where it’s prioritized, cohesion and continuity are amplified.

The Governance Gap

For decades, many Family Offices concentrated on managing investments: allocating portfolios, sourcing deals, and growing capital. Today, those priorities are evolving. The challenge is no longer “How do we make money?” — it’s “How do we keep it? How do we coordinate it? And how do we prepare the next generation to lead it?”

Recent data underscores the urgency:

86% of Family Office executives cite governance as their number one challenge.3

69% of global Family Offices now list succession planning as a core strategic focus.4

66% prioritize family wealth advisory and intergenerational training programs.4

Yet despite recognizing the need, many families are slow to act — often because governance feels abstract, emotionally charged, or secondary to immediate financial results.

The High Cost of Inaction

The absence of governance isn’t neutral. It’s destabilizing.

Without frameworks to guide decision-making, manage risk, and align stakeholders, Family Offices face:

Increased family disputes

Fragmented investment strategies

Talent flight (especially among rising generation members)

Higher exposure to succession crises

In The Fireside, a first-generation executive warns, “If you’re going to be honest, the biggest risk to most Family Offices is the family.” [2] He goes on to describe a scenario in which a patriarch’s failure to plan for succession could lead to chaos, stalled operations, and a hemorrhaging of wealth.

One generational transfer gone wrong can fracture a fortune built over decades. Without clear structures for ownership, leadership, and communication, even the most sophisticated portfolios are vulnerable.

What the Next Era Requires

Families leading the way are treating governance not as a “nice to have,” but as a strategic asset—building institutional-quality practices into private wealth structures.

Key trends defining forward-looking Family Offices include:

Family Constitutions and Charters: Clearly defined values, mission, and governance bodies.

Formal Investment Committees: With professional standards around risk management, due diligence, and accountability.

Structured Succession Planning: Leadership development programs and shadow boards for next-gen family members.

Family Councils and Communication Protocols: Regular, structured engagement across generations.

From The Fireside: “The absence of a succession plan can send the rats skittering off the decks.”

Other families are going further, embracing advisory boards composed of legal, financial, philanthropic, and next-gen governance experts. One CEO featured in Deloitte’s report explained, “We selected our board the same way you would for a public company — a financial expert, an investment expert, a lawyer who works with wealth holders, and two members focused on family dynamics and philanthropy.”2

The result? A professional-grade Family Office that aligns with fiduciary best practices and enhances trust.

Why Governance is the New Growth Strategy

At a time when investment returns are increasingly volatile, governance delivers durable value. Good governance:

Reduces strategic drift

Protects against legal and regulatory risk

Creates clarity around roles, rights, and responsibilities

Strengthens the family’s human capital alongside its financial capital

Moreover, it enables continuity in a landscape marked by volatility. One family office COO interviewed by Deloitte, after describing a painful yet successful split into multiple branches, summarized it succinctly: “Families should feel empowered to do good in their respective ways.”2

It’s no longer enough to focus on growing AUM. The real edge belongs to families that can navigate complexity, steward leadership, and foster unity across generations.

The Family Offices that will define the next era won’t be the ones that took the most risk. They’ll be the ones who built the strongest foundations.

Endnotes/Sources

Paul Westall, “Predictions For The Family Office Space In 2025,” Forbes, February 5, 2025.

Dr. Rebecca Gooch, The Family Office Insights Series – Global Edition, The Fireside, May 8, 2025.

Ocorian Family Office Study, 2024.

J.P. Morgan Private Bank, Global Family Office Report, 2024.

Lawyer on the Move: Using a Legal Recruiter

This month’s article focuses on a topic that I am repeatedly asked about, namely recruiters. Should a recruiter be used in a job search, and if so, how do I find a good one? Given the continued robust lateral market, I decided that this month’s column would focus exclusively on this popular topic.

Over the years, I’ve had the opportunity to work with some of the best recruiters in the US in connection with my lawyer mobility and ethics practice. They’ve taught me a lot about this profession from their perspective. I can say without hesitation that finding a good recruiter to help navigate through your career is critical.

Question: How do I decide whether to use a recruiter in connection with my job search?

Answer: The answer depends on multiple factors, including what type of a position you are looking for, where you are in your career, and how developed your network is in relation to that position.

The first question you must ask yourself is what type of position are you seeking? If you are looking for a position in government or in-house, it may be more effective to rely upon your network connection to make inroads into your job search because, oftentimes, recruiters are not used to helping fill those types of positions. For example, one of my friends recently left private practice for an in-house position. He secured this position because he knew several individuals who worked in the legal department at that organization. That’s why it’s critical to continue to develop relationships throughout your career and to stay in touch with former classmates and colleagues, because one never knows where that classmate or former colleague may end up working. On the other hand, if you are looking to make a lateral move from one firm to another, I would urge you to find a recruiter to assist with your search. The recruiters are most knowledgeable about which firms are looking to hire and for which positions in which offices. They have relationships with management and the recruiting staff at these law firms that can be helpful in making certain that your resume gets in front of the right person.

Second, where are you in your career? If you are just starting out and have not had an opportunity to develop your network, a recruiter is likely a wise choice. A good recruiter will spend time learning about you and your interests and can guide you in terms of which firm may be a good fit for you and why. But if you are someone who has been practicing for a period, you may know someone at a firm you would like to apply to, or someone within the organization that you can contact and ask if the organization is hiring. This contact can also describe the position for you and what it is like to work there.

Whether you choose to work with a recruiter or not, I would encourage you to conduct your due diligence regarding any position you apply for to make certain it will be a good fit for you professionally and culturally.

Question: I received a cold call from a legal recruiter at the office. I am thinking about leaving my current law firm, but I told the recruiter I was not interested and hung up pretty quickly. The reason I did that was I figured that the person on the other end of the phone might be anyone, including someone from my own firm looking to root out disloyal associates. Call me paranoid, but what’s the best way to handle a call like the one I got?

Answer: I understand how you reacted. It’s common. It’s difficult to get those calls at the office, especially if you have not had to field them before. Here are a couple of tips for you moving forward.

First, thank the person for calling. It’s not easy for a recruiter to make cold calls either, so be polite.

Second, if you would like to hear more from the recruiter, you should tell the recruiter that now is not a good time for you to speak. You can provide them with a personal email address or cell phone number, where that person can reach out to you to schedule a convenient place and time to discuss further.

Third, when the recruiter follows up, make sure you schedule a date and time where you can focus and will not be interrupted. If you are going to take the time to speak with a recruiter about a possible job search, you want to take it seriously. Prior to having such a call with the recruiter, you should put together a list of questions to ask, some of which may include: what you like/dislike about your current position; what you are looking for in a new position; and what opportunities does this recruiter have for someone at your level. You also should evaluate the recruiter during this conversation to determine if you want to work with this person. It’s important that you feel comfortable with this recruiter. The best recruiters have a genuine interest in you and will want to work with you throughout your career. During this call, while the recruiter interviews you, you should use this opportunity to interview the recruiter. Recruiters will be presenting your information to potential employers. You want to ensure that this individual acts professionally and will present your candidacy to employers using their years of experience for your benefit.

Question: What are some signs that a headhunter has strong relationships with reputable firms, and how can I assess whether they have the right connections for my practice area?

Answer: As I’ve said before, choosing a recruiter who is a good fit for you is a must. Here are a few tips to make certain you find the best fit.

First, conduct your due diligence. Does this recruiter speak and write articles about their profession? Do they have a podcast or a social media presence? Do they have a well-developed website? The best recruiters are involved in their industry and write articles about trends and hot topics that they are seeing in the lateral marketplace. Does the recruiter offer value-added services, such as assisting you with preparing a lateral partner questionnaire (LPQ) or an application that presents your information and firm metrics in a clear and concise manner? Does the recruiting firm provide its candidates with ethics counsel that can assist them in navigating ethical considerations and obligations when making a move? These are good indicators that the recruiter is reputable and has spent time and resources to invest in his or her candidates. Ask the recruiter which firms they typically work with and how many placements they handle each year. Ask how long they have been recruiting. If you are an associate, ask if they work exclusively on associate recruiting and why. If you are a partner, ask if they focus solely on partner recruiting and why. Finally, ask the recruiter which firms they typically work with and if they specialize in any types of practices. If you have a particular firm or firms in mind as part of your search, ask the recruiter if they have worked with those firms, how often, and in connection with what type of placements. These basic questions will enable you to gain insight into whether this is the correct recruiter for you.

Second, do you like this person? The best recruiters are not just looking to make a one-time placement. Rather, the best recruiters are looking to develop a long-term relationship with you and serve as an advisor to you throughout your career. If the recruiter does not make an effort to really get to know you or your practice, this may be a sign that this person is not the right fit.

Workplace Strategies Watercooler 2025: Bringing People Together During Changing Times [Podcast]

In this installment of our Workplace Strategies Watercooler 2025 podcast series, Luther Wright offers listeners an engaging discussion on how employers can create a cohesive and resilient workforce in the face of change, conflict, and uncertainty. Luther, who is the office managing shareholder of Ogletree’s Nashville office and the firm’s Assistant Director of Client Training, shares strategies for strengthening team connections, enhancing communication, and maintaining a positive work culture during uncertain times. He also provides actionable insights on leading through change while promoting unity and collaboration throughout the organization.

The Hidden Liability: Why Expert Witness Due Diligence Is No Longer Optional

In modern litigation, the strength of your expert witness can be a determining factor in the trajectory of your case. An expert’s credibility, background, and litigation history often come under intense scrutiny—both in and out of court. For attorneys, the failure to thoroughly vet an expert witness, whether retained or opposing, carries serious professional and strategic risks.

Expert Witnesses Under the Microscope

Expert testimony serves as a cornerstone in complex litigation—shaping liability, influencing damages, and framing technical issues for judges and juries alike. But with that influence comes a heightened burden: the need to ensure that an expert’s qualifications and history can withstand rigorous cross-examination and judicial scrutiny.

A growing number of cases have demonstrated how overlooked details—such as undisclosed board sanctions, prior litigation conduct, or inconsistent statements—can be leveraged by opposing counsel to impeach an expert’s credibility. Even experienced attorneys can find themselves blindsided if their expert’s record hasn’t been fully vetted. Worse, if the lapse is egregious enough, it could expose the firm to malpractice claims.

Common Pitfalls in the Vetting Process

Attorneys frequently rely on publicly available sources such as state licensing boards or disciplinary records to evaluate expert witnesses. While these are important starting points, they can be incomplete or difficult to access. Sanctions may not be updated in real-time, and some jurisdictions maintain opaque or fragmented reporting systems.

Further, expert witnesses often have extensive litigation histories, academic publications, or industry affiliations that may contain contradictory or problematic material. An expert who testifies inconsistently across cases, for example, opens the door to impeachment. Similarly, undisclosed financial relationships or conflicts of interest can call an expert’s neutrality into question.

When Expert Vetting Fails: High-Stakes Lessons from Recent Litigation

Recent high-profile cases underscore the critical importance of thoroughly vetting expert witnesses, as lapses in credibility have led to significant legal repercussions.

In the Paraquat Products Liability Litigation, (MDL No. 3004, Case No. 3:21-md-3004-NJR), thousands of plaintiffs allege that exposure to the herbicide Paraquat caused Parkinson’s disease. The plaintiffs’ sole general causation expert, a biostatistics professor, was excluded by both federal and state courts due to concerns over his methodology. This exclusion has significantly undermined the plaintiffs’ position, highlighting how even a single expert’s shortcomings can jeopardize large-scale litigation.

Meanwhile, the Karen Read trial, (Commonwealth v. Karen Read, Norfolk Superior Court, Massachusetts) has received national attention. Read is accused of murdering her boyfriend, Boston police officer John O’Keefe. The case has been marked by intense scrutiny over expert testimony and evidence handling. Notably, the defense’s use of two expert witnesses raised serious ethical and procedural concerns, leading a Massachusetts judge to suspend the retrial after discovering undisclosed payments exceeding $23,000 to experts from ARCCA LLC. The judge expressed “grave concern” over these payments and their potential to influence testimony, illustrating how non-transparent expert arrangements can threaten the integrity of a defense strategy.

These cases serve as stark reminders that expert witness credibility hinges not only on academic qualifications but also on transparency, methodology, and litigation history—all of which demand thorough and ongoing vetting.

Vetting the Opposition: A Strategic Imperative

While it’s standard practice to assess your own expert’s background, applying the same level of scrutiny to opposing experts can create valuable strategic advantages. Identifying prior credibility issues, financial incentives, or testimony that contradicts their current opinions can equip attorneys with powerful tools for cross-examination or motion practice.

This kind of intelligence gathering often goes beyond traditional research. Attorneys increasingly rely on technology-assisted review and monitoring tools that provide ongoing insight into an expert’s involvement in litigation, public commentary, and professional conduct.

How Legal Tech and AI Are Transforming Expert Witness Due Diligence

Advancements in legal technology are fundamentally reshaping how attorneys approach expert witness vetting. AI-powered tools can now aggregate and analyze vast amounts of data—spanning court filings, publications, deposition transcripts, disciplinary records, media coverage, and online content—that would take an individual attorney dozens of hours to review manually, if accessible at all.

By synthesizing this information, these technologies help attorneys identify potential red flags in both retained and opposing experts, such as inconsistent testimony, undisclosed affiliations, financial conflicts, or patterns of bias. This kind of analysis allows for a more complete and proactive assessment of an expert’s litigation history and professional conduct.

Whether leveraging sophisticated platforms or conducting manual investigations, attorneys must treat expert vetting as a critical component of case strategy. A well-documented, thoroughly scrutinized expert can offer a strategic advantage—not only at trial, but during early case evaluation, expert selection, and pre-trial motion practice.

Checklist: Key Areas to Evaluate When Vetting Expert Witnesses

To ensure credibility and minimize risk, attorneys should review the following:

Litigation HistorySearch past testimony and involvement in prior cases for inconsistencies, frequency of retention, or potential bias.

Publications & Academic WorkExamine peer-reviewed articles, books, or public statements for positions that may contradict current opinions.

Deposition & Trial TranscriptsIdentify patterns in how the expert performs under examination or how their testimony has been challenged.

Licensing & Disciplinary RecordsConfirm active licensure and check for sanctions or disciplinary actions through relevant state or professional boards.

Professional AffiliationsInvestigate organizational memberships or consulting roles that may pose conflicts of interest.

Media Coverage & Online PresenceReview interviews, social media activity, and public commentary for any material that could affect credibility.

Financial RelationshipsDisclose and evaluate payments received from parties with vested interests in the litigation.

A Heightened Standard of Care

In an era where expert testimony is increasingly under attack, courts and clients alike expect attorneys to meet a higher standard when it comes to expert witness due diligence. The ability to identify red flags—before opposing counsel does—can mean the difference between advancing your case and defending against an avoidable credibility crisis.

By leveraging the latest legal tech tools, attorneys are positioned to meet that heightened standard. These platforms do not replace legal judgment—but they elevate the investigative foundation on which sound decisions are made.

In high-stakes litigation, there is simply no substitute for knowing exactly who your expert is—and who the other side’s expert claims to be.

Weathering the Business Divorce Storm: Charting Safe Passage for Both Sides of the Transaction

Business divorces often involve turbulence as business partners go through this process. But partners who plan ahead can navigate through their business divorce to avoid capsizing the company or frustrating their personal business objectives. This type of planning requires each of the partners to (1) review and understand the terms of the agreements in place that govern their separation, (2) develop a real world, objective appraisal of the value of the interest that is being transferred, and (3) consider the business issues that may arise for both sides after the divorce, e.g., future competition by the departing minority partner.

The change and separation involved in a business divorce can be hard for all parties, but anticipating the issues that are likely to arise provides a compass for partners that will help them chart a predictable course to smooth sailing on the other side of the transaction. In the following post, we will consider the goal of becoming prepared for a business divorce from the perspective of both the majority owner purchasing the interest of the departing partner and the minority investor whose ownership interest is being purchased.

Step 1: Closely Review the Written Agreements That Apply to the Business Divorce

The first step in approaching any business divorce is to know the rules of the game.

The Majority Owner

The majority owner needs to understand whether a buy-sell agreement exists that allows the owner to redeem the interest held by the minority investor or that will permit the investor to demand a buyout. If this type of agreement is in place, it governs the manner in which either party can exercise a call or put option that will result in a redemption of the minority interest. In either case, the agreement will address how the value of the minority interest is determined, and it will also set forth the payment terms after the value of the interest is determined.

In the absence of a buy-sell agreement, the majority owner does not have the right to trigger a repurchase of the minority interest and therefore has to negotiate with the investor to find terms that are acceptable. If the investor demands payment of an excessive amount or insists on including unreasonable terms, it is likely that a buyout will not take place in the near term. In this scenario, the majority owner will have to consider taking actions that cut off all further economic benefits to the investor before a liquidity event takes place that cashes out the investor’s interest in the business. This is known as a freeze out or squeeze out situation.

Minority Investor

The minority investor also needs to determine whether a buy-sell agreement exists that permits the majority owner to exercise a call right to redeem the minority interest or that authorizes the investor to exercise a put right, which requires the majority owner to purchase the investor’s interest. The terms of the buy-sell agreement are therefore critical to fully appreciate before a business divorce is considered.

If no buy-sell agreement is in place, the good news is that the minority investor cannot be forced out of the business by the majority owner on terms the investor considers unfavorable. The bad news, however, is that the investor cannot require the majority owner to purchase the investor’s interest for the price desired by the investor if the investor wants to exit the business for any reasons. Without a buy-sell agreement, the minority investor must assess whether leverage can be obtained that will bring the majority owner to the table to discuss a buyout. This leverage may be available if the majority owner has engaged in self-dealing in managing the business. The bottom line is that the minority investor needs to evaluate the majority owner’s conduct to determine whether any misconduct by the owner will provide some leverage that the investor can apply to facilitate a buyout discussion with the owner.

Step 2: Develop a Real World (Objective) Assessment of Value

The next critical step for the partners to prepare for a business divorce is to understand the actual fair market value of the minority interest that will be changing hands.

The Majority Owner

If a buy-sell agreement exists, it will specify the method the parties must use to determine the value of the minority investor’s interest that is being purchased in the business divorce. If no buy-sell agreement exists, the majority owner will need to negotiate the purchase price directly with the minority investor. At the outset, the majority owner typically directs the company to retain an independent valuation expert to determine an objective value of the minority interest that the parties can use as the basis for their negotiation of the purchase price.

Under these circumstances, however, the majority owner should expect the minority investor to demand payment of a premium for the minority interest, because the investor has no contractual duty to sell. As long as the minority investor’s proposed purchase price is within the realm of reason, the majority owner who wants to purchase the interest should seriously consider paying a premium of some amount, because (1) the owner will secure the return of the investor’s equity in a manner that avoids a prolonged exit, (2) the purchase of the investor’s interest will avoid incurring any legal fees dealing with claims or litigation by the investor, and (3) the owner will capture all future appreciation in the value of the business.

Minority Investor

As noted above, the minority investor cannot renegotiate the purchase price for his or her interest in the company if a buy-sell agreement exists that dictates the process for determining the value of the investor’s interest. When there is no buy-sell agreement, the minority investor can choose to hold out to secure a purchase price that reflects full market value of the investor’s interest. As a cautionary note, however, the majority owner has no contractual obligation to purchase the investor’s interest in the absence of a buy-sell agreement. Therefore, if the investor drives too hard a bargain in the negotiations, the owner may simply walk away from buyout discussions and also terminate all distributions or dividends to the investor. As a result, the investor who insists on receiving top dollar for his or her minority share of the business, must be prepared to wait a very long time to be in a position to monetize his or her interest if the majority owner is not prepared to pay what the investor perceives as full value for the minority interest.

Step 3: Consider Post-Separation Business Issues

The final step in preparing for a business divorce concerns the need to consider what will take place after the business divorce has been completed.

The Majority Owner

For the majority owner, the planning process needs to address how the company will operate after the minority investor departs, which is more of a significant issue if the investor had an active role in the business. If so, the majority owner will need to take steps to arrange for a smooth transition of all duties previously handled by the investor relating to customers, vendors and the supervision of other company employees.

The majority owner will also want to ensure that the departing minority investor does not create problems for the company after leaving. First, the majority owner will want to retrieve all confidential information that is held by the investor as part of the business divorce. Second, the majority owner needs to consider whether to request the minority investor accept restrictive covenants that prevent the investor from competing with the company and from soliciting its employees for some period of time.

If the majority owner believes these restrictions on the investor are necessary, the owner will likely have to pay additional consideration to obtain them in addition to the purchase price that is paid to the investor for his interest in the business. The majority owner should require that this additional amount be paid to the minority investor over time so that the unpaid amounts can be withheld if the investor fails to comply with the restrictive covenants during the period that they remain in force.

Minority Investor

The minority investor does not need to retain confidential information that belongs to the company, but the investor does need to decide to what extent she has any interest in remaining active in the same industry as the company. If the investor wants to remain active in the industry in some capacity, the investor needs to make sure that complete clarity is reached regarding the exact scope of any restrictive covenants that the owner seeks to impose on the investor’s future conduct. The extent of the restrictive covenants will also impact the amount that the minority investor seeks as additional compensation for accepting these new restrictions.

But, if the minority investor is receiving a fair price from the majority owner for the purchase of the investor’s minority ownership interest in the business, the investor should be wary of overplaying his or her hand. If the minority investor seeks too much compensation from the majority owner in payment for the restrictive covenants that are requested by the owner, the investor may cause the entire deal to fall through and lose the opportunity to monetize the minority interest in the business for a reasonable price.

Conclusion

Most business divorces include some rough waters to cross for the partners, but if they plan ahead, they can successfully weather the storm. This advance planning requires the partners to (1) develop a keen understanding of their contract rights based on the terms of the agreements in place, (2) determine the objective, fair market value of the minority interest that is being sold in the business divorce, and (3) consider the business goals of the other partner after the business divorce has been completed.

This careful planning by business partners will enable them to navigate their way through a business divorce in a manner that saves them time and expense, preserves their relationship, and also avoids running the business into rocky shoals.

Listen to this post

Avoiding Ethical Pitfalls as Generative Artificial Intelligence Transforms the Practice of Litigation

“It has become appallingly obvious that our technology has exceeded our humanity.”

This quote from Albert Einstein warns that as technology rapidly advances, human ethical oversight is required to ensure tools are used thoughtfully and appropriately. Decades later, this quote rings loud today as generative artificial intelligence (“GAI”) transforms the practice of law in ways that eclipse even the introduction of computer-assisted legal research from Westlaw and Lexis in the 1970s.

GAI has brought about revolutionary changes in the practice of law, including litigation, over the last five years, particularly since the launch of ChatGPT on November 30, 2022, and its subsequent rise. Advancements are so major and rapid that the legal profession recently witnessed the first appearance by an avatar before a court in a real proceeding.1 In a profession governed by a defined set of principle-based ethical rules, litigators making new use of the technology will likely find themselves in an ethical minefield. This article focuses on governing ethical rules and tips to avoid violations.

Brief Overview of GAI

GAI is a powerful technology that trains itself on massive datasets – typically taking the form of large language models (“LLMs”) which mimic human intelligence allowing it to perform a variety of functions seemingly as if it were a person. GAI can analyze data, produce relevant research, and generate new product, including written material, images, and video. For ease of use, GAI functions through “chatbots,” which simulate conversation and allow users to seek assistance through text or voice. The main chatbots include ChatGPT (developed by OpenAI), Gemini (Google), Claude (Anthropic), and Copilot (Microsoft). These chatbots are all public-facing, as such any member of the public can use them. Unless the functionality is switched off, queries and information shared by a user are retained and continue to train the model meaning such information loses its confidentiality. There is also non-public-facing GAI, which utilizes proprietary models that are private to the user.

The main difference between GAI and the versions of Westlaw and Lexis that lawyers today grew up using is that GAI can do the same research and much more. Responding to conversational commands, GAI can engage in human-like functions, including creating first drafts of documents and culling document sets of all sizes for relevance and privilege.

GAI Litigation Use Cases

The early days of GAI have seen five main use cases in the litigation context as set out below.

Legal Research

In little more than a quarter century, the legal profession has seen revolutionary advances in legal research. The manual and laborious practice of visiting law libraries and pulling bound case reporters gave way to technology as Westlaw and Lexis gained widespread use in the early 1990’s with the rise of personal computers. Recent years have witnessed the next technological revolution in legal research with the advent of GAI. Searches are now simpler and available to all. Whereas traditional Lexis and Westlaw (they each now have GAI versions) rely on more primitive search terms and require a paid subscription, GAI allows for conversational commands – typed or spoken – and basic versions are available free of charge. GAI can also conduct advanced queries, such as mining vast troves of data to ensure no precedent is missed.

E-Discovery / Document Review

“Technology Assisted Review” (more commonly known as “TAR”) has materially changed e-discovery over the last decade. TAR, aka predictive coding, learns from a lawyer’s tagging of sample documents and efficiently classifies the remainder of the population. The process has dramatically sped up e-discovery and has reliably assisted with relevancy and privilege determinations. Following a seminal decision by SDNY Magistrate Judge Peck in 2012,2 where he encouraged the use of predictive coding in large data volume cases, U.S. judges have regularly approved of TAR as an acceptable (and often superior) method for identifying responsive documents.

GAI is elevating TAR to the next level. Before GAI, TAR relied heavily on keyword searches and the results were only as good as the search terms. By contrast, GAI can learn context and intent, which allows it to surface relevant documents even if they do not contain identified keywords. Similarly, GAI can learn legal concepts and flag privileged material. Unlike legacy TAR systems, which need to be re-trained for each project, GAI LLM models constantly re-train themselves and stand ready for use.

Studies have found that GAI-based review can be more accurate and efficient than human review in finding relevant material. For example, a 2024 study published by Cornell University, which pitted LLMs against humans in a contract review exercise, found that LLMs match or exceed human accuracy, LLMs complete the task in mere seconds compared to hours for humans, and LLMs offered a 99.97 percent reduction in costs.3

Legal Writing

GAI can amaze at preparing first drafts of any legal document. For a simple example, ask ChatGPT to “please draft a SDNY complaint for a 10b-5 claim where the stock price dropped 10 percent after the CEO misrepresented future prospects.” First-time users will do a double take at the results—a highly workable draft that provides both structure and the start of relevant content. Studies again confirm efficiencies—with one showing GAI cut brief-writing time by 76%.4

Trial Preparation

GAI has shown great promise in assisting trial preparation through summarizing and organizing documents, such as deposition transcripts. Aside from relevance, GAI can be used to create chronologies, and zero in on key admissions and impeachment material. GAI can be used to compare the deposition transcript to prior statements by the witness or others to speedily find inconsistencies. GAI can even generate deposition transcripts in real-time allowing questioners to raise inconsistencies that will be captured in the official record, as well as to suggest real-time relevant follow-up questions.

Predictive Analytics for Trial Outcomes

Lastly, GAI can sift through vast legal data sets to help forecast how a trial may play out. It can assess legal precedent, rulings by the judge, and even jury behavior. The analysis can get micro, focusing on issues such as how often a particular judge grants motions to dismiss and what types of arguments are most persuasive to the judge. While early days, there is a reported episode of a litigation where a law firm, which was inclined to settle, won at trial following its use of a GAI tool which predicted an 80% chance of victory.5

Ethical Issues

While the benefits are immense, use of GAI is laden with risks that must be carefully managed. As Chief Justice John Roberts stated in his 2023 year-end report, which was devoted to artificial intelligence, “Any use of AI requires caution and humility.”6 To apply caution and avoid pitfalls, lawyers should be mindful of two main concerns when using GAI:

(1) While the tools are immensely powerful in applying logic to locate and analyze material, they cannot discern the truth and they can become confused leading to erroneous output – discussed below and colloquially referred to as “hallucinations,” thereby requiring close human review; and

(2) Several of the Model Rules of Professional Conduct (and state versions thereof) apply to use of GAI and need to be complied with at the risk of attorney discipline.

The Rules

No lawyer should use GAI in practice without being aware of the following Model Rules, along with relevant states’ versions, and their application to the technology. For a more fulsome review of the governing Model Rules, practitioners would be well-served to read ABA Formal Opinion 512 dedicated to GAI.7

Competence – Rule 1.1 and ABA Comment 8 thereunder, which require that lawyers keep informed of changes in the law and its practice, including the benefits and risks associated with relevant technology.

Client Communication – Rule 1.4, which requires sharing with the client all information that can be deemed important to the client, including the means by which a client’s objectives are to be met.

Fees and Expenses – Rule 1.5, which requires that both be reasonable.

Confidentiality of Client Information – Rule 1.6, which requires informed consent from clients before disclosing their information to third parties.

Candor Toward the Tribunal – Rule 3.3, which sets forth specific duties to avoid undermining the integrity of the adjudicative process, including prohibitions on submission of false evidence.

Responsibilities of Partners, Managers and Supervisory Lawyers – Rule 5.1, which requires such persons to take reasonable steps to ensure that all lawyers in their firm conform to the Rules of Professional Conduct.

Tips to Avoid Running Afoul

While not meant to be an exhaustive list, the following tips represent critical practice points based on early GAI experience.

Do not learn GAI on the job

Lawyers’ first use of GAI should not be in connection with a live matter. Under Rule 1.1, lawyers have a duty to understand a technology–including nature of operation, benefits and risks–prior to use.8 As per ABA Formal Opinion 512, a “reasonable understanding,” rather than an expertise, is required.9 To satisfy this requirement, attorneys should be familiar with how a tool was trained, its capabilities (which tasks it can be used for) and its limitations (confidentiality, bias risk based on the data that was inputted, etc.) before using the tool.

A mishap example comes from Michael Cohen, President Trump’s former lawyer, who presented his lawyer with three non-existent cases that made their way into motion papers.10 Cohen obtained the cases from Google Bard, a GAI tool, and, upon realizing the mistake, informed the court that he “did not realize [Bard] … was a generative text service that … could show citations and descriptions that looked real but actually were not. Instead [he had] understood it to be a super-charged search engine.” The court, while describing Cohen’s belief as “surprising,” declined to impose sanctions finding a lack of bad faith.

Never submit GAI-generated research to a court or adversary without human verification of all relevant points – legal and factual.

Cohen aside, there have been at least six additional hallucination cases to date where erroneous cites were submitted to courts.11 These have included citations for cases which simply do not exist12 as well as cases which do exist but do not support the proposition they are used to support.13 Accordingly, it is not enough to solely verify citations – rather, it must be confirmed that the citation stands for the point represented. These matters have involved law firms big14 and small,15 showing the risks do not only reside at small firms looking to save on the costs of Lexis and Westlaw.

These risks are real and material. A June 2024 Stanford University study found that leading legal research GAI tools hallucinate between 17% and 33% of the time.16 The consequences can be severe, ranging from professional embarrassment17 to Rule 11 sanctions to referrals to bar associations for potential discipline based on competence violations

Promptly notify the court and adversaries of any known inaccuracy generated by GAI.

Should an error occur, it is imperative to promptly notify the court and adversaries. The duty of candor imposed by Rule 3.3 requires that lawyers correct any material false statement of law or fact made to a tribunal. Prompt remedial action can also persuade the judge to refrain from imposing sanctions for submission of the hallucination.18

Never input client information into a GAI tool without informed client consent and an evaluation of attendant risks.

As stated clearly in ABA Formal Opinion 512 and its analysis of Rule 1.6 governing the confidentiality of client information, “[B]ecause many of today’s self-learning GAI tools are designed so that their output could lead directly or indirectly to the disclosure of information relating to the representation of a client, a client’s informed consent is required prior to inputting information relating to the representation into such a GAI tool.” Informed consent should come from a direct documented communication and not from statements made in boilerplate engagement letters.

Consent aside, Rule 1.1 governing competence requires an evaluation of the disclosure risks of inputting such information, including from use by the public, others within the same firm but walled off from the matter, and via cyber breaches. As a baseline, practitioners should read the Terms of Use, privacy policy and other contractual terms applicable to the GAI tool being used. Such review such focus on: the confidentiality provisions in place; who has access to the tool’s data; the cyber controls that are in place; and whether the information is retained by the tool after the lawyer’s use is discontinued. Even if the system is custom to a firm, issues can still arise if others within the firm, but not working on the matter, can inadvertently view such data.

Never input client information into a public-facing GAI tool, period.

Client information should never be inputted into a public facing GAI tool such as Chat GPT. While Chat GPT keeps conversations private by default, its OpenAI architecture uses chat to improve model performance (i.e., for training) unless the user opts out. Risks of disclosure of client information are too great and consequence too severe (violations of ethical rules and waiver of attorney-client privilege and work product protections), such that client information should not be shared with such tools.

Discuss with the client any use of GAI to help form litigation strategy.

Rule 1.4 requires lawyers to advise the client promptly of information which would be important for the client to receive, including the means by which the client’s objectives are to be accomplished. As such, lawyers should consult with their client prior to using GAI to influence a significant litigation decision. As stated in ABA Formal Opinion 512, “A client would reasonably want to know whether, in providing advice or making important decisions about how to carry out the representation, the lawyer is exercising independent judgment or, in the alternative, is deferring to the output of a GAI tool.” By contrast, it is unlikely that using GAI to conduct research gives rise to a consultation requirement, just as it is not the practice to do so today when using Westlaw or Lexis.

Ensure all fees and expenses tied to GAI use are reasonable.

Rule 1.5 provides that a lawyer’s fee must be reasonable and the basis for the charges must be communicated to the client. The new terrain of GAI can lead to violations of this rule. Under ABA Formal Opinion 93-379, lawyers cannot bill for more time than worked. While GAI can speed up the completion of many tasks, lawyers may only bill for the actual time spent on such task, even if compressed. Next, as per ABA Formal Opinion 512, it is permissible for lawyers to bill for the time to input data and run queries, as well as to learn a tool that is custom to the client. By contrast, it is not permissible to bill for the time spent learning a tool that will be used broadly within a lawyer’s practice. As to expenses, as per ABA Formal Opinion 93-379, absent an agreement, a lawyer can charge a client no more than the direct cost associated with the tool plus a reasonable allocation of related overhead – no surcharges or premiums may be added. Flat fee arrangements give rise to their own considerations – as per Model Rule 1.5, the fee must be “reasonable,” which would not always be the case if GAI allowed the project to be completed in rapid fashion. Here, price adjustments may be in order. As stated in Formal Opinion 512, “A fee charged for which little to no work was performed is an unreasonable fee.”

Managerial lawyers must take steps to ensure those at their firm comply with the rules.

To ensure compliance with Rule 5.1, law firms should establish clear policies and provide training on the appropriate use of GAI prior to allowing such use.

Conclusion

As its use takes off, GAI is likely to have several material impacts on the practice of law, including: reducing the demand for law firm associates as research, first drafts of documents, first level document review, and other traditional tasks performed by these lawyers will now be handled by computer; an increase in cost reduction pressure given clients’ greater expectation of efficiencies; and the potential for higher quality product given a broader landscape of data which can be efficiently surveyed for relevance and more lawyer time available for strategy and tactical decisions.

Increased future use of GAI will also assuredly result in more errors, hallucinations and otherwise. To guard against the consequences of missteps, practitioners should follow the tips herein as but a baseline for good practice.

1 See Larry Newmeister, An AI Avatar Tried To Argue A Case Case Before A New York Court. The Judges Weren’t Having it,” AP News, April 4, 2025 (Discussing a March 26, 2025 proceeding before the New York State Supreme Appellate Division, where a panel of judges shut down an attempt by a pro se plaintiff to show a video of his argument delivered by an avatar moments into delivery. The court scolded the attorney and required him to deliver his argument himself).

2 Da Silva Moore v. Publicis Groupe, 287 F.R.D. 182 (SDNY 2012).

3 Lauren Martin, Nick Whitehouse, Stephanie You, Lizzie Catterson, and Rivindu Perera, Better Call GPT, Comparing Large Language Models Against Lawyers, Cornell University (January 24, 2024).

4 Bob Ambrogi, CaseText Study Says Its ‘Compose’ Technology Cuts Brief-Writing Time by 76%, LawSites (July 28, 2020).

5 Ashley Hallene and Jeffrey M. Allen, Using AI for Predictive Analytics in Litigation, ABA website, October 2024.

6 Chief Justice John Roberts, 2023 Year-End Report on the Federal Judiciary at 5.

7 ABA Formal Opinion 512, Generative Artificial Intelligence Tools, July 29, 2024.

8 ABA Comment 8 to Model Rule 1.1 (“[A] lawyer should keep abreast of changes in the law and its practice, including the benefits and risks associated with relevant technology.”

9 Id. at 2.

10 U.S. v. Cohen, 18-CR-602 (JMF) (SDNY March 20, 2024)

11 Sara Merken, AI “hallucinations’ in court papers spell trouble for lawyers, Reuters (Feb. 18, 2025) (citing to at least seven such cases over the prior two years).

12 See Mata v. Avianca Airlines, No. 22-CV-1461 (SDNY June 22, 2023)[INSERT PARENTHETICAL]; Wadsworth v. Walmart LLC, No. 2:23-CV-118-KHR (D. WY Feb. 24, 2025) (lawyers sanctioned for citing six cases that do not exist in a motion to dismiss); U.S. v. Cohen, 18-CR-602 (JMF) (SDNY March 20, 2024) (sanctions considered but not imposed on Michael Cohen and his attorney for citing to three cases that do not exist). Iovino v. Michael Stapleton Assoc., No. 5:21-cv-00064 (W.D. Va. July 24, 2024) (sanctions considered but not imposed on lawyer for citing two cases that do not exist).

13 Iovino, id (also citing two cases for quotes that are not found in the opinions).

14 See Wadsworth, supra note 8 (AmLaw 100 firm filed a motion citing eight cases that do not exist).

15 See, e.g., Mata v. Avianca Airlines, [cite] (two lawyers fined $5,000).

16 Varun Magesh, Faiz Surani, Matthew Dahl, Mirac Suzgan, Christopher D. Manning, and Daneil E. Ho, Hallucination-Free? Assessing the Reliability of Leading AI Legal Research Tools, Stanford University (June 6, 2024).

17 Negative press aside, the lawyers in the Avianca Airlines matter were ordered to send the judge’s opinion sanctioning them – which called their filing “legal gibberish” – to the judges to whom the GAI improperly attributed the fake citations. Similarly, in the Michael Cohen matter, Judge Furman described the episode as “embarrassing” and “unfortunate.” Cohen, supra note 8.

18 Iovino v. Michael Stapleton Assoc., No. 5:21-CV-64, Transcript of Order to Show Cause Proceeding, (W.D. VA Oct. 9, 2024).

Financial Planning Strategies for Founder-Owned Law Firm Transitions

Transitioning from a first-generation to a second-generation law firm is a complex and multifaceted process. It requires careful planning, clear communication, and a thorough understanding of the financial, operational, and cultural implications. This section provides a comprehensive overview of the essential financial planning components of a successful transition plan, offering insights and strategies to law firm leaders.

Understanding the Transition Process

The transition process in founder-owned law firms involves a series of steps that significantly impact the firm’s future. Healthy firms with accurate information can expedite the process, while those lacking profitability and strong financial reporting may need remedial action.

Action Step:

Conduct a thorough financial assessment of the firm to identify areas needing improvement before starting the transition process.

The Importance of Financial Planning

A transition-oriented financial plan must address several critical elements:

Cash flow, debt, and equity over the transition period

Effect of transition compensation on earnings for the firm and assuming equity owners

Profitability of transitioned work

Effect of multiple transitions occurring simultaneously

Scenario planning at various levels of transitioned work

Exit costs in the event of a failed implementation

Action Step:

Develop a detailed financial plan that includes projections for cash flow, debt, equity, and profitability.

Cash Flow, Debt, and Equity

The capital structure of many firms relies on a combination of trade credit, bank and other interest-bearing debt obligations, and owners’ equity (direct contributions and undistributed earnings). Preparing equity owners for the possible need for additional capital ensures that sufficient cash is available for retirement payments.

Action Step:

Communicate with partners about the potential for increased debt or capital contributions to support the transition.

Effect of Transition Compensation

The impact of a retiring partner’s compensation is either distributed among all partners or only those participating in the transition plan. Firms must decide on the most equitable method.

Action Step:

Calculate the pro forma effect on remaining partners’ compensation to ensure transparency and fairness.

Profitability of Transitioned Work

Projecting future profits post-transition is crucial. This includes considering changes in the staffing mix and the impact on profitability.

Action Step:

Perform profitability analysis for key client relationships to determine post-transition financial viability.

Multiple Transitions

Simultaneous transitions can strain a firm’s resources. To manage the financial burden, some firms cap combined transition costs at a percentage of net income.

Action Step:

Establish guidelines for managing multiple transitions to prevent overtaxing the firm’s resources.

Scenario Planning

We recommend modeling best and worst-case scenarios to prepare for various outcomes. This includes considering the risks and additional resource costs in case of failure.

Action Step:

Develop a monitoring system to detect issues early in the transition process and allocate resources accordingly.

Exit Costs

Firms must also consider the costs associated with a failed transition. Clear agreements on compensation can mitigate financial risks.

Action Step:

Define exit costs within the transition agreement to handle potential failures effectively.

Establishing a Credible Process

A well-defined and repeatable process adds credibility to a firm’s transition strategy. This competitive advantage can attract and retain top talent, ensuring the firm’s long-term success.

Action Step:

Document the transition process and communicate it clearly to all stakeholders.

Summary

Transitioning a founder-owned law firm to a second-generation leadership involves meticulous financial planning, transparent communication, and strategic scenario planning. Firms can successfully navigate this complex process by addressing critical elements such as cash flow, profitability, and multiple transitions. Establishing a credible and repeatable process ensures long-term stability and growth.

Unfair Competition and Chapter 93A: Takeaways from Governo Law Firm LLC v. Bergeron

The Massachusetts Appeals Court recently reviewed a Chapter 93A Section 11 claim for a second time. Plaintiff Governo Law Firm LLC alleged that former employees secretly copied files while still employed by the firm and later used them to compete unfairly. After the initial trial, the jury found the defendant liable of conversion but determined that the former employees did not violate Chapter 93A Section 11. The Supreme Judicial Court vacated that portion of the judgment and remanded for a new trial on that claim.

After a subsequent bench trial, the trial judge found that defendants did not violate Section 11 because their unfair and deceptive conduct did not harm or injure plaintiff law firm.

On appeal, the court found that the trial court’s findings related to a lack of harm or injury was based on clear error. The appeals court reversed the Chapter 93A judgment and remanded for entry of a new judgment in plaintiff’s favor and an assessment of damages consistent with the court’s opinion.

The bench trial found that after failed sale negotiations at plaintiff law firm, defendants prepared to leave in order to begin their own firm. Prior to departing, the defendants copied electronic files to external drives that they brought with them to their new firm. Once the new firm was established, most clients that the departing attorneys represented decided to transfer their business to the new law firm. The trial court thus concluded that while defendants acted unfairly and deceptively when they secretly copied the electronic materials and took them to the new firm before they had any clients, the firm did not suffer a loss or injury since the defendants only accessed materials that belonged to clients who ultimately transferred their business.

The appeals court was not persuaded by this no-harm, no foul approach. Specifically, defendants took an organizational system they developed while employed at the plaintiff law firm in order to streamline their practice. This database was not the type of material that the Rules of Professional Conduct contemplate would be transferred when a client transfers their business to a new firm. The appeals court determined that the clients who ultimately left plaintiff firm were not entitled to the entire database that was developed to efficiently represent multiple clients defending against similar claims, even if those clients paid for some portion of the time used to create and update the database. While at the new law firm, the defendants did not rebuild the database and re-enter the data record by record from current client files. Instead, they used the copied materials to “find and access discovery materials, investigatory materials, [and] case history summaries.” That evidence was adequate to establish unfair and deceptive conduct and that the violation was willful or knowing. The use of the copied materials harmed plaintiff law firm. The appeals court then remanded for an assessment of damages (including attorney’s fees) based on a disgorgement of profits theory resulting from unfair competition. The parties may present experts on remand to determine the appropriate amount of damages. This case demonstrates the scope of the “loss of money or property” requirement for Section 11 claims.

Can AI Replace Lawyers? The UPL Challenge

Introduction

A popular refrain echoes through legal technology conferences and webinars: “Lawyers won’t be replaced by AI, but lawyers with AI will replace lawyers without AI.” This statement offers a degree of comfort to legal professionals navigating rapid technological advancement, suggesting AI is primarily an augmentation tool rather than a replacement. While many practitioners hope this holds true, a fundamental question remains: Is it legally possible for AI, operating independently, to replace lawyers under the current regulatory frameworks governing the legal profession? As it stands, the rules surrounding the unauthorized practice of law (UPL) in most jurisdictions present a significant hurdle.

The UPL Barrier: Protecting the Public, Impacting Access

All jurisdictions in the United States have established rules prohibiting the unauthorized practice of law. These regulations typically mandate that individuals providing legal services must hold an active license issued by the state bar association. The primary stated goal is laudable: to protect the public from unqualified practitioners who could cause significant harm through erroneous advice or representation.

However, these well-intentioned rules have downstream consequences, notably impacting efforts to broaden access to justice. By strictly defining what constitutes legal practice and who can perform it, UPL rules can limit the scope of services offered by non-lawyers and technology platforms, even for relatively straightforward matters. For instance, the State Bar of California explicitly notes on its website that immigration consultants, while permitted to perform certain tasks, “cannot provide you with legal advice or tell you what form to use” – functions often essential for navigating complex immigration procedures.1

Legal Tech’s Current Role vs. Direct-to-Consumer AI

Much of the legal technology currently deployed operates comfortably within UPL boundaries because it serves as a tool for lawyers. AI-powered research platforms, document review software, and case management systems enhance a lawyer’s efficiency and effectiveness. Crucially, the licensed attorney remains the ultimate provider of legal advice and services to the client, vetting and utilizing the technology’s output.

The UPL issue arises dramatically when the lawyer is removed from this equation. If a software platform or AI system interacts directly with a consumer, analyzes their specific situation, and provides tailored guidance or generates legal documents, regulators may argue that the technology provider itself is engaging in the unauthorized practice of law.

Historical Precedents: Technology Pushing Boundaries

This tension is not new. Technology companies have long tested the limits of UPL regulations. The experiences of LegalZoom offer a prominent example. The company faced numerous disputes with state bar associations regarding whether its automated document preparation services constituted UPL. In North Carolina, for instance, LegalZoom entered into a consent judgment allowing continued operation under specific conditions, including oversight by a local attorney and preserving consumers’ rights to seek damages.2

DoNotPay, once marketed as the “world’s first Robot Lawyer,” also faced and settled UPL lawsuits. Its potential as a UPL test case is complicated by recent regulatory action; DoNotPay agreed to a Federal Trade Commission (FTC) order to stop claiming its product could adequately replace human lawyers. The FTC complaint underpinning this order alleged critical failures, including a lack of testing to compare the AI’s output to human legal standards and the fact that DoNotPay itself employed no attorneys.3

The Patchwork Problem: State-by-State Variation

The LegalZoom saga underscores a critical challenge: UPL rules are determined at the state level. While general principles are similar, specific definitions and exemptions vary significantly, creating a complex regulatory patchwork for technology companies seeking national reach.

Texas, for example, offers a statutory exemption. Its definition of the “practice of law” explicitly excludes “computer software… [that] clearly and conspicuously states that the products are not a substitute for the advice of an attorney.”4 This suggests a pathway for sophisticated software, provided the appropriate disclaimers are prominently displayed.

A Proactive Model: Ontario’s Access to Innovation Sandbox

In contrast to reactive enforcement or broad statutory exemptions, some jurisdictions are exploring proactive, structured approaches. The Law Society of Ontario’s Access to Innovation (A2I) program provides an interesting example.5 A2I creates a regulatory “safe space” or sandbox, allowing approved providers of “innovative technological legal services” to operate under specific conditions and oversight.

Applicants undergo review by the A2I team and an independent advisory council. Approved participants enter agreements outlining operational requirements, such as maintaining insurance, establishing complaint procedures, and ensuring robust data privacy and security. During their participation period, providers serve the public while reporting data and experiences back to the Law Society. This process allows for real-world testing and informs future regulatory policy. Successful participants may eventually receive a permit for ongoing operation. Currently, 13 diverse technology providers, covering areas from Wills and Estates to Family Law, operate within this framework.

The AI Chatbot Conundrum and the Path Forward

Modern AI chatbots often exhibit behaviour that sits uneasily with UPL rules. Frequently, they preface interactions with disclaimers stating they are not providing legal advice, only then to proceed with analysis and suggestions that closely resemble legal counsel. While this might satisfy the Texas exemption, regulators in many other jurisdictions could view it as impermissible UPL, regardless of the disclaimer.

Ontario’s A2I model offers an appealing framework for fostering innovation while maintaining oversight. However, the core strength of many technology ventures lies in scalability. Requiring separate approvals and adherence to distinct regulatory frameworks in every jurisdiction presents a formidable barrier to entry and growth for AI-driven legal solutions intended for direct consumer use.

Conclusion

While AI is undeniably transforming the practice of law for existing attorneys, the notion of AI replacing lawyers faces a steep legal climb due to UPL regulations. The historical friction between technology providers and regulators persists. While some jurisdictions like Texas provide explicit carve-outs, and others like Ontario are experimenting with regulatory sandboxes, the lack of uniformity across jurisdictions remains the most significant obstacle.

For AI to move beyond being merely a lawyer’s tool and become a direct provider of legal guidance to the public at scale, a significant evolution in the regulatory landscape is required. Whether this takes the form of model rules, interstate compacts, or broader adoption of supervised innovation programs like Ontario’s A2I, addressing the UPL challenge will be critical to balancing public protection, access to justice, and the transformative potential of artificial intelligence in the legal sphere.

1 https://www.calbar.ca.gov/Public/Free-Legal-Information/Unauthorized-Practice-of-Law

2 Caroline Shipman, Unauthorized Practice of Law Claims Against LegalZoom—Who Do These Lawsuits Protect, and is the Rule Outdated?, 32 Geo. J. Legal Ethics 939 (2019).

3 https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2025/02/ftc-finalizes-order-donotpay-prohibits-deceptive-ai-lawyer-claims-imposes-monetary-relief-requires

4 Tex. Gov’t Code Ann. § 81.101 (West current through 2023)

5 https://lso.ca/about-lso/access-to-innovation