Trump Administration Files Statement of Interest Supporting State AG Action Against Asset Managers Accused of ESG-related Antitrust Violations

Last week, the Trump Administration’s FTC and DOJ (Antitrust Division) filed a statement of interest in support of a lawsuit filed last November by eleven Republican state attorneys-general against three major asset managers for alleged antitrust violations. This lawsuit is founded upon a novel application of antitrust law; in essence, the state attorneys-general have alleged that, under the guise of responding to environmental concerns, the three asset managers engaged in a scheme to reduce coal output (enabled by their market power–i.e., extensive holdings of stock in coal companies), and so increased the price of electricity (and profits for the coal companies). It is especially unusual as it relies upon collusive efforts by minority shareholders to reduce output across an entire industry in the pursuit of additional profits, rather than an explicit agreement among competitors to reduce competition or increase prices. Nonetheless, the use of antitrust law to pressure ESG-focused investing has been a legal tactic embraced over the past few years by elements of the GOP.

The fact that the FTC and the Antitrust Division have decided to weigh in on a prominent lawsuit is not especially surprising; noteworthy cases attract substantial attention from amici curiae, including the federal government, due to the potential significant of such cases for future litigation or the development of the law. Other prominent organizations, such as SIFMA, have also made filings in the case.

What is perhaps more interesting is how the positions adopted in the legal filing by the federal government are directly tied to the policy priorities of the Trump Administration. Indeed, the press release issued by the DOJ in conjunction with this filing makes that point clear, as it specifically invokes recent executive orders by President Trump concerning energy policy–including Exec. Order 14261, which expressly encouraged increasing domestic coal production–and how this statement of interest was intended to combat efforts “to harm competition under the guise of ESG.” While the fact that the policy priorities of the Trump Administration are guiding legal strategy is not especially surprising, this case provides a noteworthy and concrete example of this broader agenda.

Justice Department and Federal Trade Commission File Statement of Interest on Anticompetitive Uses of Common Shareholdings to Discourage Coal Production Thursday, May 22, 2025 Today, the Justice Department, joined by the Federal Trade Commission (the “Agencies”) filed a statement of interest in the Eastern District of Texas in the case of Texas et al. v. BlackRock, Inc. The States’ lawsuit—led by the Texas Attorney General—alleges that BlackRock, State Street, and Vanguard used their management of stock in competing coal companies to induce reductions in output, resulting in higher energy prices for American consumers. This is the first formal statement by the Agencies in federal court on the antitrust implications of common shareholdings.

www.justice.gov/…

Is There A Contemporaneous Membership Requirement For LLC Inspections?

The Nevada Limited Liability Company Act provides “a manager” of a limited liability company “shall promptly deliver . . . a copy of the information required to be maintained by paragraphs (1), (2), and (4) of subdivision (d) of [s]ection 17701.13” “[u]pon the request of a member” of the limited liability company “for purposes reasonably related to the interest of that person as a member.” Cal. Corp. Code § 17704.10(a). In Perry v. Stuart, 2025 WL ______________, the plaintiff was a member of the LLC both at the time of making a request for records and at the time that the member’s lawyer filed a petition seeking to enforce inspection. The defendant countered that standing was lost when the plaintiff’s membership interest was redeemed. The Court of Appeal sided with the plaintiff:

The Act does not state that a limited liability company member loses its right to request documents under section 17704.10 if it ceases being a member after making such a request. Nor does Milestone identify any language in the statute that supports such a reading. Indeed, the Act does not include amongst the effects of dissociation a loss of the right to request corporate records under section 17704.10 or otherwise cross-reference that provision. (§ 17706.03.).

(footnote omitted).

Customs Fraud Investigations Will Be a DOJ Area of Focus

On May 12, 2025, Department of Justice (DOJ) Criminal Chief Matthew Galeotti issued a memorandum addressing the “Fight Against White-Collar Crime.” The memorandum lists several priorities for white-collar criminal prosecutions. While the first priority – healthcare fraud and federal program and procurement fraud – is not surprising, the second priority – trade and customs fraud, including tariff evasion – is a new focus.

Emphasizing its new focus on trade and customs fraud, the Criminal Division is also amending the Corporate Whistleblower Awards Pilot Program to add trade, tariff and customs fraud by corporations to the list of subject matters that whistleblowers can report for a potential bounty. Under this program, previously reported here, whistleblowers can recover a percentage of the government’s ultimate forfeiture amount.

Looking at previous trade and customs cases provides insight into both how the DOJ may be planning to pursue them and what whistleblowers are likely to report. The alleged misconduct in tariff evasion cases generally falls in three areas that affect the duties owed: (1) misrepresenting the classification/type of product, (2) undervaluing the product, and (3) misrepresentation of the country of origin and/or transshipment cases. Even well-intentioned companies may find themselves making missteps in these areas because the nuance in the governing regulations makes them surprisingly complicated. Appropriate classification of a product can be challenging, and the country of origin is often unclear when manufacturing occurs in multiple countries.

Civil False Claims Act Cases

As our regular blog readers know, the False Claims Act (FCA) is a federal law that imposes civil liability for submitting false claims to the federal government. The law imposes treble damages and civil penalties on those who submit false claims. In fiscal year 2024, FCA settlements and judgments totaled over $2.9 billion. Under the FCA, whistleblowers (called “relators”) can file cases under seal on behalf of the government. The government then opens an investigation to determine whether they should intervene in the case. Much like they can share in criminal forfeitures through the Corporate Whistleblower Awards Pilot Program discussed above, the relators who bring FCA violations to the government’s attention share in the civil recovery obtained by the government.

International Vitamins Corporation

In January 2023, International Vitamins Corporation (IVC) entered a civil settlement for $22,865,055, admitting that it misclassified 32 of its products imported from China under the HTS as duty-free, over an almost five-year period. IVC also admitted that even after it retained a consultant in 2018 who informed IVC that it had been misclassifying the covered products, IVC failed to implement the correct classifications for over nine months and never remitted duties that it knew it had previously underpaid to the United States because of its misclassification. This case was originally brought as a whistleblower lawsuit by a former financial analyst at IVC (U.S. ex rel. Welin v. International Vitamin Corporation et al., Case No. 19-Civ-9550 (S.D.N.Y.)).

Samsung C&T America, Inc. (SCTA)

In February 2023, Samsung C&T America, Inc. (SCTA) resolved a FCA lawsuit that was initially filed by a whistleblower. SCTA admitted that, between May 2016 and December 2018, it misclassified imported footwear under the United States’ Harmonized Tariff Schedule (HTS) and underpaid customs duties. SCTA further admitted that it had reason to know that certain documents provided to its customs brokers inaccurately described the construction and materials of the imported footwear and that SCTA failed to verify the accuracy of this information before providing it to its customs brokers.

SCTA, with its business partner, imported footwear manufactured overseas, including from manufacturers in China and Vietnam. The tariff classifications for footwear depend on the characteristics of the footwear, including the footwear’s materials, construction, and intended use. Depending on the classification of the footwear, the duties varied significantly.

In the settlement agreement, SCTA specifically admitted and accepted responsibility for the following conduct:

As the importer of record (IOR), SCTA was responsible for paying the customs duties on the footwear and providing accurate documents to the United States Customs and Border Protection (CBP) to allow CBP to assess accurate duties.

SCTA and its business partner provided SCTA’s customs brokers with invoices and other documents and information that purportedly reflected the tariff classification of the footwear under the HTS, as well as the corresponding materials and construction of the footwear. SCTA knew that its customs brokers would rely on the documents and information to prepare the entry summaries submitted to CBP, which required classifying the footwear under the HTS, determining the applicable duty rates, and calculating the amount of the customs duties owed on the footwear.

SCTA had reason to know that certain documents provided to its customs brokers, including invoices, inaccurately stated the materials and construction of the footwear. SCTA failed to verify the accuracy of this information before providing it to its customs brokers. Thus, SCTA materially misreported the classification of the footwear under the HTS and misrepresented the true materials and construction of the footwear.

SCTA, through its customs brokers, misclassified the footwear at issue on the associated entry documents filed with CBP and, in many instances, underpaid customs duties on the footwear.

This case makes clear that the company and/or IOR bears responsibility for accurately reporting to CBP and that the government will not allow an importer to pass the blame to the customs broker when it has reason to know that it is providing the customs broker with inaccurate information.

Ford Motor Company

In March 2023, Ford Motor Company (Ford) agreed to pay the United States $365 million to resolve allegations that it violated the Tariff Act of 1930 by misclassifying and understating the value of hundreds of thousands of its Transit Connect vehicles. This settlement is one of the largest recent customs penalty settlements.

While Ford did not admit to any wrongful conduct, the settlement resolves allegations that it devised a scheme to avoid higher duties by misclassifying cargo vans. Specifically, the government alleged that from April 2009 to March 2013, Ford imported Transit Connect cargo vans from Turkey into the United States and presented them to CBP with sham rear seats and other temporary features to make the vans appear to be passenger vehicles. The government alleged that Ford included these seats and features to avoid paying the 25% duty rate applicable to cargo vehicles instead of the 2.5% duty rate applicable to passenger vehicles. The settlement also resolves allegations that Ford avoided paying import duties by under-declaring to CBP the value of certain Transit Connect vehicles.

King Kong Tools LLC (King Kong)

In November 2023, a German company and its American subsidiary agreed to pay $1.9 million to settle allegations of customs fraud under the FCA. The government alleged that King Kong was falsely labelling its tools as “made in Germany” when the tools were really made in China. By misrepresenting the origin of the tools, King Kong avoided paying a 25% tariff.

This case began when a competitor of King Kong filed a whistleblower complaint alleging that King Kong was manufacturing cutting tools in a Chinese factory (U.S. ex rel. China Pacificarbide, Inc. v. King Kong Tools, LLC, et al.,1:19-cv-05405 (ND Ga.) ). The tools were then shipped to Germany, where additional processing was performed on some, but not all, of the tools. The tools were then shipped to the United States and declared to be “German” products.

Homestar North America LLC

In December 2023, Homestar North America LLC (Homestar) agreed to pay $798,334 to resolve allegations that it violated the FCA by failing to pay customs duties owed for furniture imports from China between September 2018 and December 2022. The government alleged that the invoices were created and submitted to the CBP containing false, lower values for the goods. The settlement resolved allegations that Homestar and its Chinese parent company conspired to underreport the value of imports delivered to Homestar following two increases on Section 301 tariffs for certain products manufactured in China under the HTS.

This case was filed by a whistleblower in the Eastern District of Texas under the FCA, and the government subsequently intervened (U.S. ex rel. Larry J. Edwards, Jr. v. Homestar North America, LLC, Cause No. 4:21-cv-00148 (E.D. Tex.)).

Alexis LLC

In August 2024, women’s apparel company Alexis LLC agreed to pay $7,691,999.63 to resolve a FCA case also initially filed by a whistleblower (U.S. ex rel. CABP Ethics and Co. LLC v. Alexis et al., Case No. 1:22-cv-21412-FAM (S.D. Fla.)). The settlement, which was not an admission of liability by Alexis, resolved claims that from 2015 to 2022 Alexis materially misreported the value of imported apparel to CBP and thereby avoided paying the customs duties and fees owed on the imports. Alexis did, however, admit and acknowledge certain errors and omissions regarding the value and information reported on customs forms. Specifically, the errors related to failure to include and apportion the value of certain fabric and garment trims, discrepancies between customs forms and sales-related documentation, misclassifying textiles, and listing incorrect ports of entry.

In negotiating this settlement, Alexis and its senior management received benefits for its cooperation with the government. For example, Alexis voluntarily and timely submitted relevant information and records to the government. These submissions assisted the government in determining the amount of losses. Also, Alexis and its management implemented compliance procedures and employee training to prevent future issues.

Criminal Case

Kenneth Fleming and Akua Mosaics, Inc. (Akua Mosaics)

Kenneth Fleming and Akua Mosaics, Inc. plead guilty to a conspiracy to smuggle goods into the United States under 18 U.S.C. §§371 and 545. According to the plea agreements, from 2021 through June 2022, the defendants conspired to defraud the United States by smuggling and importing porcelain mosaic tiles manufactured in China by falsely representing to the CBP that the merchandise was of Malaysian origin. This was done with the intent to avoid paying antidumping duties of approximately 330.69%, countervailing duties of approximately 358.81%, and other duties of approximately 25%.

Fleming and Akua Mosaics conspired with Shuyi Mo, a citizen and resident of China who was arrested when he was attempting to flee the United States. They caused “Made in Malaysia” labels to be placed on boxes containing tiles manufactured in China and then caused a container with tiles manufactured in China to be shipped from Malaysia to Puerto Rico, misrepresenting the country of origin as Malaysia. The amount of unpaid duties and tariffs on this shipment was approximately $1.09 million. At sentencing, Fleming was ordered to pay restitution of $1.04 million and was sentenced to two years of probation.

Takeaways

Based upon DOJ’s new prioritization of trade and customs fraud, companies that import or export goods should ensure that they have the resources and training for employees working in jobs related to customs. Even simple errors and omissions could have more significant monetary consequences with increased tariffs. Companies should implement compliance programs to properly train employees and to identify and correct any issues as they occur.

Companies should also work with experienced trade counsel to determine if they are following the law. Failure to heed trade counsel’s advice could potentially put a company in a worse situation, like in the IVC matter discussed above.

If there is any indication of a criminal or civil investigation, companies should be proactive in retaining counsel with expertise in this area. Regardless of whether they dispute or settle the matter, experienced counsel is key in reaching a favorable resolution. Counsel can help determine when and how best to cooperate with the government to maximize cooperation credit in any settlement, as discussed above in the Alexis LLC matter.

Finally, companies should be diligent in their employment law practices. That means not only complying with applicable employment law when dealing with whistleblowers, but also ensuring that personnel files are appropriately documented when there are employee issues. FCA whistleblowers are often former, disgruntled employees who were terminated for performance issues. However, the employees’ files often do not reflect their poor performance, which can create unnecessary challenges in defending whistleblower claims. Companies that import or export goods should expect to see more whistleblowers come forward, both as traditional FCA relators and because DOJ has now added trade, tariff, and customs fraud issues to the Criminal Division’s Corporate Whistleblower Awards Pilot Program. All such companies will be best served by being diligent and prepared for DOJ’s new focus in this area.

Listen to this post

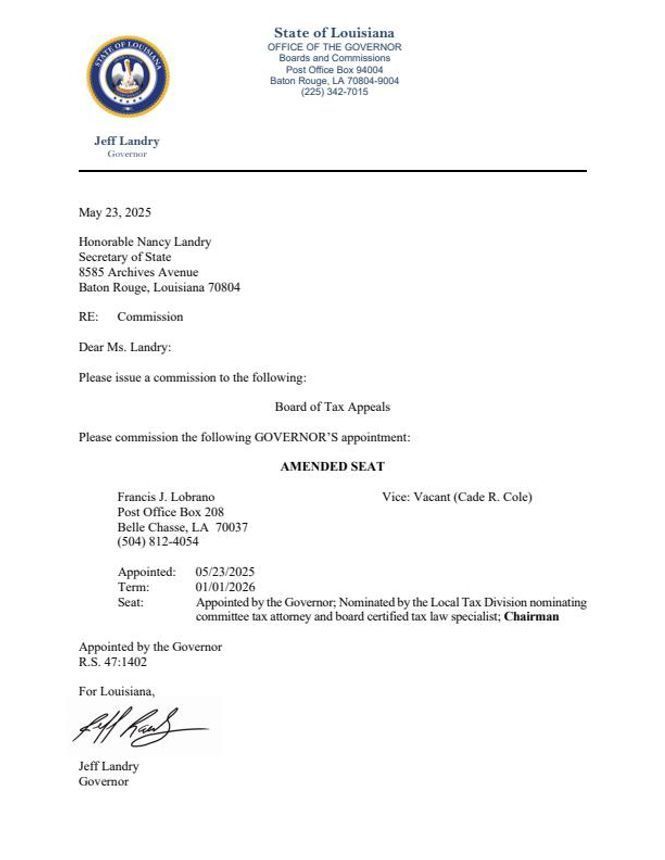

Judge Jay Lobrano Appointed Local Tax Judge at the Board of Tax Appeals

On May 23, 2025, Louisiana Governor Jeff Landry appointed Francis J. (Jay) Lobrano as the Local Tax Judge of the Louisiana Board of Tax Appeals to complete the term of outgoing Local Tax Judge, now Louisiana Supreme Court Justice Cade Cole.

Judge Lobrano has served as the Chairman of the Board since March of 2022, and has served as a member of the Board since April 2016. In his new role, Judge Lobrano will preside over all local tax matters pending at the Board, including sales and use tax disputes between Parish tax administrators and taxpayers, as well as legality challenges involving property tax assessments.

Judge Lobrano will still sit as the Chairman of the full Board, that hears tax matters involving state tax matters.

Open File0.17MB

The First Amendment, Front and Center – SCOTUS Today

The U.S. Supreme Court did not issue any merits opinions today, but there were two dissents from denials of cert. that merit attention, both concerning the First Amendment.

One of them has particular importance for parents interested in the rights and limits of their children’s self-expression in their schools. The other, which affects only a small group of people, is worthy of note, if for no other reason than that it is passionately and beautifully written.

The first of these cases that could not command the votes of four Justices, the number required for cert. to be granted, was L.M. v. Town of Middleborough. As Justice Alito, who was joined in dissent by Justice Thomas, asserted, the case which the dissenters believed was one “of great importance for our Nation’s youth” concerning “whether public schools may suppress student speech either because it expresses a viewpoint that the school disfavors or because of vague concerns about the likely effect of the speech on the school atmosphere or on students who find the speech offensive.”

The case concerned a middle school that, according to the dissent, “permitted and indeed encouraged student expression endorsing the view that there are many genders.” The petitioner, a seventh grader, was barred from class unless he removed a t-shirt that said “There Are Only Two Genders,” and a later version where the words “Only Two” was blocked out and overwritten with “CENSORED.” When the student, through his parents, sued, claiming a violation of his First Amendment rights, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit ruled against him, holding that the general prohibition against viewpoint-based censorship does not apply to public schools. While there was no written explanation for the majority’s denial of cert., the dissenters question its consistency with Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School Dist., 393 U. S. 503 (1969).

This blog takes no position on whether the Court was justified in denying cert. as a matter of school discipline and concern for students who identify as non-binary or otherwise gender non-specific, or was, as the dissenters argue, an exercise in political correctness. Nevertheless, this latest chapter in a continuing sequence of cases concerning the application of the First Amendment in school settings is worthy of attention.

The second case that could not command four votes for cert. was Apache Stronghold v. United States, and it should be unsurprising that the primary dissenter was Justice Gorsuch, who, joined by Justice Thomas, sided with an Indian band of Western Apache. Gorsuch has always shown himself to be a strong supporter of Indian rights and interests. This case concerns a site known as Chích’il Bił Dagoteel, or Oak Flat, which the Indians consider to be sacred and a “direct corridor to the Creator,” and where the tribe conducts “religious ceremonies that cannot take place elsewhere.” While Oak Flat had long been a protected site, the government engaged a mining contractor to turn the site into what Justice Gorsuch called “a massive hole in the ground” to gain access to and extract copper. This crater—perhaps 1,000 feet deep and nearly two miles wide—will permanently “destroy the Apaches’ historical place of worship, preventing them from ever again engaging in religious exercise” at Oak Flat.

Acting on behalf of the tribe in attempting to block the destruction of their sacred site, an interest group sued under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 (RFRA), claiming a violation of their free exercise of religion. Readers might remember RFRA, a law that prevents the federal government from “substantially burden[ing] a person’s exercise of religion,” as the centerpiece of several free exercise and establishment cases, perhaps most notably, Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc. The picture painted by Justice Gorsuch’s rich and poignant discussion is consigned to our memory and conscience, but no further consideration by a Court that could not summon four votes to grant certiorari.

These dissents from the denial of cert. are to be consigned to the catalog of unanswered prayers. Sometimes, those petitions are worth knowing about for the quality of their writing and their contributions to public discourse about issues of concern in a divided society.

Should Miller be Set Aside? Observations from a Recent U.S. Supreme Court Decision Regarding a Trustee’s Power to Set Aside Fraudulent Transfers

The U.S. Supreme Court recently decided United States v. Miller, which resolved a circuit split over whether a trustee could avoid federal tax payments under section 544(b) of the United States Bankruptcy Code.[1] In this case, a trustee utilized section 544(b) to claw back tax payments under Utah’s state fraudulent transfer statute. Ordinarily, an action under Utah law against the federal government would be barred by sovereign immunity; however, section 106(a) of Bankruptcy Code contains a waiver of sovereign immunity with respect to section 544(b). Despite this, the Supreme Court held that the sovereign immunity waiver under section 106(a) only applies to section 544 itself, and not to the state-law claims “nested” within the statute.

Background

The underlying facts of the case concerned a Utah-based transportation company, All Resort Group, which became insolvent in 2013 following financial struggles and the misappropriation of company funds by two of its shareholders. In 2014, these shareholders transferred $145,000 of company funds to the IRS to pay for their personal income tax obligations. In 2017, All Resort Group filed for bankruptcy. Shortly thereafter, the trustee sued the United States under section 544(b) seeking to avoid the 2014 tax payments as fraudulent transfers under Utah state law. The United States argued that sovereign immunity prevented the trustee’s cause of action under Utah law, while the trustee argued that section 106(a) waived the government’s sovereign immunity with respect to section 544(b). The parties cross-moved for summary judgment. The Bankruptcy Court for the District of Utah entered judgment for the trustee, holding that sovereign immunity did not preclude the trustee from suing because of the waiver under section 106(a). The District Court and the Tenth Circuit affirmed the Bankruptcy Court’s decision. This further entrenched a circuit split where the Fourth and Ninth Circuits had previously sided with a trustee, while the Seventh Circuit had sided with the government—and the Supreme Court granted certiorari.

Avoidance Powers

Under chapter 5 of the Bankruptcy Code, trustees have avoidance powers that permit a trustee to recover certain assets for the benefit of the bankruptcy estate. There is a strong policy justification for these avoidance powers, because they enable trustees to equalize distributions among creditors, and prevent debtors from offloading assets to preferred creditors on the eve of bankruptcy. Specifically, section 544(b) permits a trustee to “avoid any transfer of an interest of the debtor . . . that is voidable under applicable law by a creditor holding an unsecured claim.” 11 U.S.C. § 544(b)(1). State laws, like the Uniform Voidable Transfers Act and the Uniform Fraudulent Transfer Act, provide a common basis for a trustee to invoke section 544(b) and generally provide creditors with a cause of action to invalidate fraudulent transfers.

The Interplay between Sections 106 and 544

The crux of the dispute involved how broad section 106(a) of the Bankruptcy Code may be. The relevant portions of section 106(a) read: “sovereign immunity is abrogated as to a government unit to the extent set forth in this section with respect to . . . (1) section[] 544,” and “(5) [n]othing in this section shall create any substantive claim for relief or cause of action not otherwise existing under this title, the Federal Rules of Bankruptcy Procedure, or nonbankruptcy law.” The trustee argued that section 106 provided a broad waiver of sovereign immunity for both section 544(b) and the “applicable law” invoked by this section, whereas the government argued the waiver applied only to section 544(b) itself and did not extend to the “applicable law” nested within section 544(b). According to the majority, the government had the better reading.

The Supreme Court explained that section 544(b) requires a bankruptcy trustee to identify an actual creditor who could have set aside the transaction under applicable law. If there is no actual creditor who could have set aside the transaction, then the trustee is prohibited from avoiding the transaction. In this case, no actual creditor would be able to avoid the federal tax payment under Utah law (because of sovereign immunity), and therefore, section 106(a) cannot provide a backdoor into creating liability for the government. The Court explained that the legislative history bolsters this reading, quoting the relevant House and Senate Reports, which provide “the policy followed here is designed to achieve approximately the same result that would prevail outside of bankruptcy.” The Court cited other sovereign immunity precedents for the proposition that sovereign immunity waivers are typically jurisdictional in nature and concluded that construing section 106(a) as applying to and modifying the elements of section 544(b) would be a “highly unusual understanding of sovereign-immunity waivers.” The Court also explained that the text of section 106(a)—that it does not “create any substantive claim for relief or cause of action not otherwise existing”—plainly refutes the argument that section 106(a) extends to both section 544(b) and its elements (the underlying “applicable law”).

In sum, the Supreme Court held that while section 106(a) abrogates sovereign immunity for causes of action under section 544(b), it did not abrogate sovereign immunity under the state-law claim that supplied the “applicable law” under section 544(b).

The Dissent

In a short dissent, Justice Gorsuch reasoned that because the parties did not dispute that a fraudulent transfer claim existed under Utah law, the “applicable law” element of section 544(b) was satisfied, even though the defendant was the federal government. In Justice Gorsuch’s view, sovereign immunity would operate as an affirmative defense to such a suit, but that here, the waiver in section 106(a) prohibited the government from raising this defense. Justice Gorsuch reasoned that applying the section 106(a) waiver to the “applicable law” did not “modify the elements” of 544(b) and concluded that trustees should be permitted to avoid fraudulent transfers to the federal government.

Observations and Takeaways

The majority opinion drives the point home that the key analysis of section 544(b) is whether an actual creditor could prevail against a party outside of bankruptcy, despite the term “actual” not appearing in section 544(b)’s text. Here, since an actual creditor would not prevail against the federal government outside of bankruptcy because of sovereign immunity, the Trustee could not maintain a claim. This ruling will provide guidance to attorneys engaged in disputes even outside of the sovereign immunity context, as it reinforces that a trustee cannot succeed in bringing an avoidance action pursuant to state law if an existing creditor cannot prevail under that law.

Interestingly, the Supreme Court’s holding can be read to be in direct tension with the fundamental principle of bankruptcy that creditors in equal positions should be treated equally—meaning, in this context, that prepetition transfers to preferred creditors should be prohibited. Indeed, preventing these and making such transfers also available to other creditors is the entire purpose of a trustee’s avoidance powers.

[1] U.S. v. Miller, 604 U.S. ___ (2025).

Biopharmaceutical Patent Litigation: Regeneron’s Defense Against Biosimilar Launches

This case[1] involves an appeal from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.’s (Regeneron) efforts to prevent defendants from marketing biosimilar versions of EYLEA®, a drug used to treat eye diseases, by asserting patent infringement. In particular, the Federal Circuit addressed issues of personal jurisdiction, preliminary injunctions, and patent validity.

Background

Regeneron holds a Biologics License Application (BLA) for EYLEA®, which contains a fusion protein called aflibercept that acts as a vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) antagonist. This drug is commonly used for treating angiogenic eye diseases through intravitreal administration. Regeneron also owns patents related to the formulation and use of this drug. In 2022, Samsung Bioepis (SB) and other companies filed for FDA approval of EYLEA® biosimilars, prompting Regeneron to file patent infringement lawsuits against SB and other defendants. The case was consolidated in the Northern District of West Virginia, where another defendant is incorporated.

In the district court, Regeneron sought preliminary injunctions against SB and other defendants to prevent the sale of biosimilars that allegedly infringed on Regeneron’s patents. The district court granted Regeneron’s motion for a preliminary injunction, finding that Regeneron was likely to succeed on the merits of its patent infringement claims. The court determined it had personal jurisdiction over SB based on SB’s filing of an abbreviated BLA (aBLA) and its plans for nationwide distribution of its biosimilar product. SB contested these findings, arguing against the court’s jurisdiction and the validity of the preliminary injunction. Subsequently, SB appealed the district court’s decisions to the Federal Circuit, challenging both the jurisdictional ruling and the grant of the preliminary injunction.

Issue(s)

Whether the West Virginia district court had personal jurisdiction over SB, a South Korean company, based on its interactions and agreements related to the U.S. market.

Whether Regeneron demonstrated a likelihood of success on the merits and the threat of irreparable harm, justifying the preliminary injunction against SB.

Whether SB raised substantial questions regarding the validity of Regeneron’s patents, particularly concerning obviousness-type double patenting and written description sufficiency.

Holding(s)

The Federal Circuit affirmed that the district court had personal jurisdiction over SB, as SB had established distribution channels for its biosimilar that included West Virginia.

The Federal Circuit upheld the preliminary injunction against SB, finding that Regeneron met all the necessary factors, including likelihood of success and irreparable harm.

SB did not raise a substantial question of invalidity under the doctrines of obviousness-type double patenting or lack of written description support.

Reasoning

Regarding personal jurisdiction, the Federal Circuit found that SB’s filing of an aBLA, coupled with its agreement with Biogen to distribute the biosimilar nationwide, constituted sufficient minimum contacts with West Virginia. The Court emphasized that SB’s plans for nationwide distribution, without excluding any states, further supported jurisdiction.

Regarding the preliminary injunction, the Federal Circuit evaluated the four relevant factors: likelihood of success on the merits, potential for irreparable harm, balance of hardships, and public interest. Regeneron demonstrated a likelihood of success given the strength of its patent claims and SB’s inability to present a substantial invalidity defense. The Court found that Regeneron would suffer irreparable harm through market share loss and price erosion if SB launched its biosimilar. The balance of hardships favored Regeneron because Regeneron would suffer significant market disruption and loss of goodwill if the biosimilar products were launched, whereas SB would not face comparable harm from a delay in entering the market, given that the injunction would only temporarily prevent their entry until the patent issues were resolved. And, finally, the public interest supported enforcing valid patent rights.

On the issue of obviousness-type double patenting, the Federal Circuit concluded the patent at issue was patentably distinct from the reference patent, particularly due to its specific stability and glycosylation limitations. Regarding written description, the Court held that the patent at issue’s specification adequately supported the claims, with sufficient disclosure of the claimed stability levels of glycosylation.

In conclusion, the Federal Circuit upheld the district court’s decision to grant a preliminary injunction against SB, affirming that personal jurisdiction was appropriate and that Regeneron was likely to succeed on the merits of its patent infringement claims. The Court found no substantial question of patent invalidity, reinforcing the strength of Regeneron’s patent rights against marketing biosimilar versions of EYLEA®. This decision underscores the importance of detailed patent specifications and robust patent rights in biopharmaceutical patent litigation.

FOOTNOTES

[1] Regeneron Pharms., Inc. v. Mylan Pharms. Inc., Amgen USA, Inc., Biocon Biologics Inc., Celltrion, Inc., Formycon AG, Amgen Inc., Samsung Bioepis (Defendant-Appellant) No. 2024-1965, 2024-1966, 2024-2082, 2024-2083 (Fed. Cir. Jan. 29, 2025)

Preliminary Injunction of Recent DoD + GSA Memo Means Federal Contractors Must Continue to Comply with Biden-Era Project Labor Agreement EO + FAR

Takeaways

The injunction vacates federal agencies’ memoranda exempting certain construction projects from mandatory PLA requirements.

Executive Order 14063 (EO) and related Federal Acquisition Regulations requiring PLAs on large-scale federal construction projects remain in effect.

Despite the injunction, the Trump Administration is likely to continue scaling back the use of PLAs on federally funded projects.

A D.C. federal judge granted the North America’s Building Trades Union and Construction Trades Council’s request to enjoin the recent memoranda exempting certain construction projects from Executive Order (EO) 14063. North America’s Building Trades Unions (NABTU) v. Department of Defense et al, No. 1:25-cv-01070 (DDC May 16, 2025).

Executive Order 14063 is a Biden-era rule requiring every federal contractor to enter into a Project Labor Agreement on federal construction projects over $35 million. The Federal Acquisition Regulatory Council implemented this rule in 2023 as a Federal Acquisition Regulation. In February 2025, the Department of Defense (DOD) and Federal General Services Administration (GSA) issued memoranda purportedly eliminating this requirement. The North America’s Building Trade Union’s filed suit seeking to enjoin the DOD and GSA memoranda.

The court held the two unions demonstrated a substantial likelihood of establishing that the memoranda are contrary to law and violate the Administrative Procedure Act in deviating from the EO requirements without “providing adequate justification or following the proper exception process.” The court further noted that agencies are bound by EOs until they are “rescinded or overridden through lawful procedures.” Accordingly, the DoD and GSA memoranda were vacated.

PLA Basics

A PLA is a pre-hire, collective bargaining agreement that contractors enter with one or more labor organizations establishing terms and conditions of employment for a specific construction project. The PLA can include dispute resolution procedures, wages, hours, working conditions and bans on work stoppages.

Under the EO, non-union contractors may bid for and work on covered federal PLA projects, but they must abide by the terms of the PLA (and the applicable terms of collective bargaining agreements referenced therein) for the duration of that project. For contractors already signatory to a union contract, the PLA is an additional layer to the existing union agreement. The non-union contractor need not sign on to union agreements for other work not covered by the PLA.

Executive Order 14063

Former President Joe Biden signed Executive Order 14063, Use of Project Labor Agreements for Federal Construction Projects, on Feb. 4, 2022. That order provided that, with certain exceptions, government contractors and subcontractors working on federal construction projects that meet the threshold of $35 million must “become a party to a project labor agreement [PLA] with one or more appropriate labor organizations.”

The order explained that PLAs “avoid labor-related disruptions on projects by using dispute-resolution processes to resolve worksite disputes and by prohibiting work stoppages, including strikes and lockouts.”

On Dec. 22, 2023, the FAR Council, after issuing a proposed rule and receiving public comment, issued its final rule implementing the EO, with minimal changes to its proposed regulations.

Trump Administration Impact

The lawsuit highlights ongoing legal challenges over the Biden Administration’s mandatory PLA requirements. Recently, in MVL USA Inc. v. United States, several construction companies filed a lawsuit in the U.S. Court of Federal Claims challenging the legal authority of federal agencies to mandate PLAs under the EO. 174 Fed. Cl. 437 (Fed. Cl. 2025). The court found in favor of the construction companies, holding the PLA mandate, as applied in those cases, violated full and open competition under the Competition in Contracting Act because it excludes responsible offerors declining to enter PLAs, even when the data indicates an exception should be made. While the D.C. Circuit noted in NABTU v. DoD that the holding was limited to the specific procurements in that case, the case will likely serve as precedent when future bidding challenges arise.

Nonetheless, President Trump is expected to make efforts to revoke or scale back the mandate during his administration. On March 14, 2025, for example, he issued EO 14236 (Additional Rescissions of Harmful Executive Orders and Actions) which revoked Biden-era EO 14126 (Investing in America and Investing in American Workers) that encouraged federal agencies to prioritize projects involving PLAs, among other pro-labor agreements. EO 14236 does not impact the PLA mandate, but it does indicate the Trump Administration will, at the very least, minimize the use of PLAs going forward.

Although the district court decision is subject to appeal, the federal PLA mandate is still in effect. Construction employers should therefore anticipate that large-scale federal projects may require PLAs that comply with EO 14063’s requirements.

Umbrella Insurer’s “Business Decision” to Pick Up an Insured’s Defense Leads to a Multi-Million Dollar Fraudulent Concealment Claim

A primary insurer (Truck Insurance Exchange) and an umbrella insurer (Federal Insurance Company) have been involved in a series of lawsuits dating back to 2007. The California Court of Appeal recently ruled that their litigation is not done yet. Truck Ins. Exch. v. Fed. Ins. Co., No. B332397, 2025 WL 1367172, ___ Cal. Rptr. 3d ___ (2025).

Truck and Federal insured a company named Moldex-Metric, Inc., which was named as a defendant in several civil lawsuits. Initially, Moldex was defended and indemnified by various primary insurers.

In 2003, when the primary insurers’ limits were purportedly exhausted, Federal – which had issued a commercial umbrella policy to Moldex – began to indemnify Moldex and pay for its defense. However, in late 2004, Moldex discovered it was an additional insured under a primary liability policy issued by Truck. This ultimately led to three different lawsuits between Federal and Truck.

Lawsuit #1: Federal first sued Truck seeking contribution for indemnity and defense costs that Federal had paid on Moldex’s behalf. Federal argued, among other things, that as an umbrella/excess insurer, Federal had no duty to indemnify or defend Moldex until all primary policies were exhausted – including Truck’s. The trial court ruled in Federal’s favor. While the case was on appeal, Truck reached a settlement with Federal as part of which Truck agreed to pay more than $4.8 million in defense and indemnity costs.

Lawsuit #2: Truck later sued Federal (and other defendants) seeking reimbursement or contribution for defense and indemnity costs that Truck paid after its policy limits were exhausted. In response, Federal argued Truck could not seek reimbursement from Federal for defense costs because Federal had no duty to defend Moldex; rather, Federal claimed that it “made a business decision” to exercise its right to associate in Moldex’s defense. Specifically, Federal relied on a provision in its umbrella policy that stated it “shall not be called upon to assume” the defense of any suits brought against Moldex, but that Federal “shall have the right and be given the opportunity to be associated in the defense,” which if it chose to do would be at Federal’s “own expense.” Federal ultimately prevailed in that second lawsuit, in part, based on that argument.

Lawsuit #3: Truck then filed a fraud action against Federal that alleged, among other things, that Federal had misrepresented to Truck that Federal had a duty to defend Moldex or, alternatively, that Federal concealed that it had voluntarily made defense payments as a “business decision.” Truck argued that had it known that Federal’s payments were voluntary, Truck never would have entered into the $4.8 million settlement because Federal would not have had a basis to seek contribution from Truck for defense costs that Federal voluntarily assumed.

That fraud action went to a bench trial. After considering extensive evidence, the trial court issued a tentative statement of decision in Federal’s favor finding that Federal had no duty to disclose to Truck that Federal did not have a duty under its umbrella policy to defend Moldex. The court also concluded that even if the evidence supported that Federal had committed fraud, that fraud was intrinsic to Lawsuit #1 and therefore protected by the litigation privilege. Truck objected to the trial court’s tentative, including because it did not address Truck’s alternative concealment claim. The trial court disagreed and entered judgment in Federal’s favor, which Truck appealed.

The California Court of Appeal reversed. First, the court held that the trial court failed to address Truck’s concealment claim – which was not that Federal concealed it had no duty to defend under its policy, but that Federal concealed that it made a “business decision” to voluntarily assume that duty. In doing so, the court rejected Federal’s argument that it was not acting as a “volunteer” simply because it was motivated to avoid potential bad faith liability to Moldex. The court also recognized that “California law does not require one insurer to contribute to or reimburse another insurer who makes a voluntary payment.”

Second, the court held that Truck’s concealment claim was not barred by the litigation privilege. The court concluded that during Lawsuit #1, Truck did not unreasonably neglect to explore whether Federal had voluntarily assumed the defense of Moldex. Of note, the court pointed to how Federal had alleged in its complaint in that lawsuit that Truck was “obligated” to reimburse Federal for defense costs, which was inconsistent with Federal voluntarily assuming a defense obligation. Moreover, Federal never disclosed during discovery anything that indicated that it had made a voluntary “business decision” to defend Moldex. Therefore, the court agreed with Truck that Federal’s alleged concealment would amount to extrinsic fraud, which does not fall under the litigation privilege.

Accordingly, the Court of Appeal remanded the case to the trial court with instructions to hold a new trial on Truck’s concealment claim.

There are lessons to be learned on both sides of this dispute. For primary insurers, when faced with a contribution claim from an excess insurer, it’s important to closely review the excess insurance policy to assess the nature of the excess insurer’s obligations to the insured – e.g., whether it does or does not have a duty to defend. That could impact the excess insurer’s right to seek contribution from a primary insurer, in particular, if the excess insurer’s payments could be considered voluntary.

As for excess insurers, be aware that voluntarily assuming an obligation not owed under the terms of the policy could impact your right to seek recovery from other insurers.

Massachusetts Appeals Court Affirms Treble Damages for Knowing Chapter 93A Violation

In Wicked-Lite Supply, Inc. v. Woodforest Lighting, Inc., the Massachusetts Appeals Court examined whether a seller’s conduct in a commercial lighting transaction violated Chapter 93A, Sections 2 and 11, and if the conduct was knowing or willful enough to warrant multiple damages. The plaintiff, having experienced repeated failures with purchased lights, received only blame-shifting and inadequate remedies from the seller. Despite knowledge of defects, the seller insisted there was no problem and provided knowingly incompatible replacement lights. Discovery revealed the seller was aware of the faulty lights. Despite additional discussions about resolving the matter, the seller did not fix the problem and made the buyer feel like “a hamster on a wheel.” The trial judge found a Chapter 93A violation and awarded treble damages due to the defendant’s willing and knowing misconduct.

Appeals Court Analysis

On appeal, the defendant argued the conduct amounted to a simple breach of contract (which the jury had found), not a Chapter 93A violation, especially since the jury found no breach of the implied warranty of merchantability. Thus, the defendant contended, the jury necessarily rejected the premise that the defendant knowingly sold a product that it knew or should have known was defective. The Appeals Court disagreed, explaining that whether conduct violates Chapter 93A is based on “the totality of the circumstances.” The court reaffirmed that conduct need not attain “the antiheroic proportions of immoral, unethical, oppressive, or unscrupulous conduct, but need only be within any recognized or established common law or statutory concept of unfairness” to violate Chapter 93A. The trial judge had found the Chapter 93A violation was distinct from any breach of contract or related warranty issues, based on the defendant’s knowledge of defects and persistent, unfounded assurances that nothing was wrong, which were in essence, misrepresentations.

Willfulness, Knowledge, and Multiple Damages

The Appeals Court upheld the award of treble damages, noting that multiple damages under Chapter 93A were warranted based on the egregiousness of the conduct. The Appeals Court was bound by the trial judge’s findings of fact, which were supported by the evidence and all reasonable inferences drawn from that evidence. Here, the evidence was sufficient to prove willfulness and knowledge to support multiple damages.

The Appeals Court contrasted this case with VMark Software, Inc. v. EMC Corp., where the defendant “acted in good faith in its dealings with the plaintiff” and fully expected the product would function as represented. The defendant in that case also was “persistently ready and willing, though ultimately unable, to correct” the issue. Thus, in VMark Software, multiple damages were not appropriate.

Key Takeaways

This decision underscores that Chapter 93A findings are highly fact-specific. Courts will assess both the unfairness of the conduct and the willfulness of the violation under the totality of the circumstances when determining liability and damages. Also, in the context of dealings with customers, the decision underscores the importance of attempting to resolve problems in good faith and not giving customers the “runaround.”

Federal Court Strikes Down Key Portions of EEOC Harassment Guidance

On May 15, a Texas federal court vacated portions of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s (EEOC) Enforcement Guidance on Harassment in the Workplace, concluding that the agency’s expanded interpretation of “sex” under Title VII exceeded its statutory authority (Texas, et al. v. EEOC, 2:24-CV-173).

This decision has immediate, nationwide implications for employers, particularly with respect to workplace policies addressing harassment based on gender identity and sexual orientation.

Background and Scope of the Ruling

The EEOC’s guidance, adopted in 2024 by a narrow 3-2 vote, faced internal opposition, notably from the Acting Chair Andrea Lucas, who objected to provisions treating denial of access to facilities consistent with an individual’s gender identity and intentional misuse of names or pronouns as harassment under Title VII. President Trump’s Executive Order titled “Defending Women from Gender Ideology Extremism and Restoring Biological Truth to the Federal Government,” excluded gender identity from the definition of sex and directed federal agencies to align policies with “biological truth.” As a result, the EEOC was instructed to amend any conflicting guidance. However, due to a lack of quorum, the agency has been unable to formally rescind or revise the guidance. In response to the Executive Order, Lucas declared a change in the agency’s priorities, emphasizing the protection of women from sex-based discrimination by rolling back policies associated with gender identity. These changes involve deactivating the agency’s “pronoun app,” removing non-binary gender markers from discrimination charge forms, and purging EEOC resources of materials that promote gender ideology.

In its ruling, the Texas court determined that certain provisions — specifically all language defining “sex” in Title VII to include “sexual orientation” and “gender identify,” harassment based on sexual orientation and gender identity, and all language defining “sexual orientation” and “gender identity” as a protected class — exceeded the EEOC’s statutory authority and conflicted with existing law. As a result, the court vacated these sections on a nationwide basis.

Vacated Guidance

The vacated guidance of these provisions likely means the EEOC will not be filing litigation alleging discrimination on the basis of sex or gender identity. The EEOC has already withdrawn a number of cases alleging discrimination on the basis of gender identity and has marked these sections on its website to help identify which provisions are no longer operative. This includes guidance and examples related to harassment based on sexual orientation or gender identity, such as intentional misgendering and denial of access to sex-segregated facilities aligned with an individual’s gender identity.

Implications for Employers

Employers should still proceed with caution where these issues arise. The US Supreme Court has interpreted Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to prohibit discrimination rooted in sex-based stereotypes, beginning with its decision in Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins in 1989. This interpretation was further expanded in 2020 with Bostock v. Clayton County when the Supreme Court held that adverse employment actions against individuals because of their sexual orientation or transgender status are forms of sex discrimination. However, given the Texas decision, future clarification is likely. Moreover, there are a number of state and local laws that expressly prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity.

Employers should closely monitor further developments from the EEOC and the courts. In the interim, it is advisable to review workplace policies and training materials to ensure they are consistent with applicable federal and state law and to seek legal guidance on handling complaints related to gender identity and sexual orientation.

Weekly Bankruptcy Alert May 27, 2025 (For the Week Ending May 25, 2025)

Covering reported business bankruptcy filings in Massachusetts, Maine, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island, and Chapter 11 bankruptcy filings in New York and Delaware listing assets of more than $1 million.

Chapter 11

Debtor Name

BusinessType1

BankruptcyCourt

Assets

Liabilities

FilingDate

Broadway Realty I Co., LLC2(New York, NY)

Activities Related to Real Estate

Manhattan(NY)

$500,000,001to$1 Billion

$500,000,001to$1 Billion

5/21/15

Carbon Sequestration III, LLC(San Francisco, CA)

Other Financial Investment Activities

Wilmington(DE)

$10,000,001to$50 Million

$100,000,001to$500 Million

5/22/25

Chapter 7

Debtor Name

BusinessType1

BankruptcyCourt

Assets

Liabilities

FilingDate

Paravel Inc.(New York, NY)

Retail Trade

Wilmington(DE)

$1,000,001to$10 Million

$10,000,001to$50 Million

5/19/25

Northrop and Johnson Yacht Charters, Inc.(Portsmouth, RI)

Consumer Goods Rental

Providence(RI)

$0to$50,000

$500,001to$1 Million

5/21/25

Repapers Corporation(New York, NY)

Miscellaneous Durable Goods Merchant Wholesalers

Manhattan(NY)

$1,000,001to$10 Million

$10,000,001to$50 Million

5/21/25

1Business Type information is taken from Bankruptcy Court filings, which may include incorrect categorization by the debtor or others.

2Lead case filed. Please contact Pierce Atwood for information about additional affiliate filings.