USPTO Memorandum Bifurcating PTAB Institution Process Signals Shift Toward Increased Discretionary Denials in IPR and PGR

New Interim Process for Patent Trial and Appeal Board Workload Management

The USPTO has fundamentally altered the PTAB institution decision framework through a March 26, 2025, memorandum from Acting Director Coke Morgan Stewart. In a significant departure from existing practice, the memorandum details the Acting Director’s decision to bifurcate discretionary denial determinations from merits-based reviews. This update analyzes the procedural changes and their implications for PTAB practice.

Understanding Discretionary Denial Authority

The Director of the USPTO has long claimed broad statutory authority under 35 U.S.C. §§ 314(a) and 324(a) to deny institution of IPR and PGR proceedings, even when petitioners meet the threshold showing of unpatentability. The US Supreme Court confirmed in United States v. Arthrex (2021) that “Congress has committed the decision to institute inter partes review to the Director’s unreviewable discretion.” This “discretionary denial” power allows the USPTO to decline review for reasons unrelated to the technical merits of the petition — such as parallel district court litigation timing (so-called Fintiv denials), serial petitioning (General Plastic denials), or prior consideration of the same arguments (Advanced Bionics/325(d) denials).

Historically, this discretionary denial authority has been delegated to the three-judge PTAB panel assigned to each petition, which considered both discretionary and merits-based grounds simultaneously when evaluating institution. The Acting Director’s new memorandum fundamentally changes this approach by removing responsibility for decisions on discretionary denial from the PTAB’s panels and vesting it in the Director herself.

The Complex Pre-Institution Timeline Under the New Process

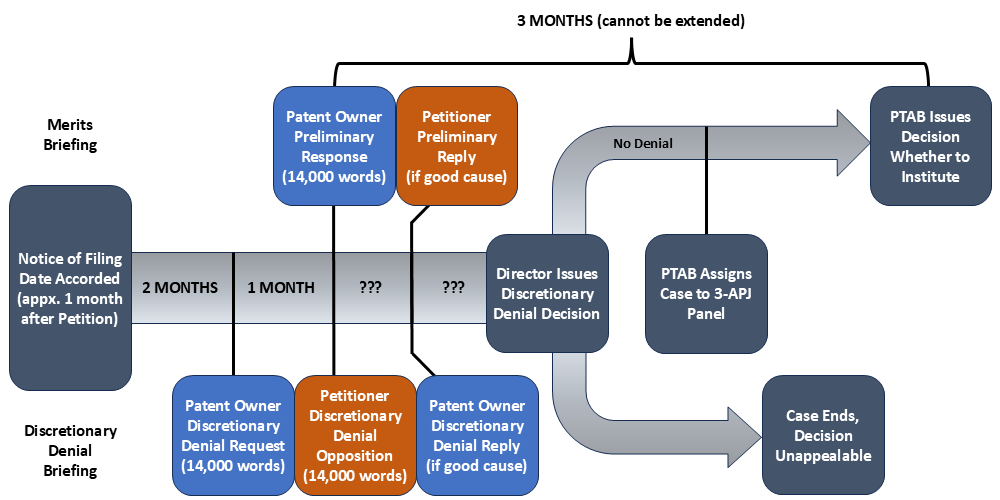

The new bifurcated approach creates a complex pre-institution process with distinct phases for discretionary and merits considerations:

Notably, the statutory three-month clock for the PTAB’s institution decision begins running at the Preliminary Response filing date. This creates an unprecedented scheduling challenge. If the Director must personally decide discretionary issues for more than a hundred petitions monthly, the discretionary review process could take considerable time, even with the assistance of several APJs. This delay in addressing the petition’s merits will likely consume a significant portion of the statutory window between the Petitioner’s discretionary denial brief and the institution decision, leaving the merits panel with limited time to evaluate the case if the Director decides against discretionary denial. (If the Director grants Patent Owner a discretionary denial reply, this time period for evaluation on the merits is shortened even further.) The memorandum provides no guidance on how the PTAB will manage these overlapping timelines or what will happen if the Director’s discretionary review extends too close to the statutory institution deadline, delaying assignment of a case to a merits panel.

Workload Management: Justification and Context

The memorandum explicitly cites “current workload needs of the PTAB” as the driving force behind these procedural changes, with a stated aim to “improve PTAB efficiency, maintain PTAB capacity to conduct AIA proceedings, reduce pendency in ex parte appeals, and promote consistent application of discretionary considerations.” This workload concern appears directly connected to recent federal workforce policies affecting the USPTO.

The Trump administration’s “fork-in-the-road” deferred resignation program, government-wide hiring freeze, and return-to-office mandates have anecdotally led to significant attrition among Administrative Patent Judges (APJs). With approximately a dozen APJs taking the “fork” offer, and others announcing early retirement, a reasonable estimate is that the PTAB has already lost approximately 10 percent of its judge corps in recent months. While the USPTO memorandum characterizes this situation as “temporary,” it is unclear how the situation is likely to improve in the near term. In fact, PTAB Chief Judge Scott Boalick recently notified his organization to prepare for a reduction-in-force (RIF).

However, the Acting Director’s memorandum implementing an entirely new process for evaluating discretionary denials raises questions about how workload benefits will be realized by the PTAB. Realistically, more than three APJs will need to “consult” with the Director to keep pace with the 100-plus petitions filed each month, as it is reasonable to assume that patent owners will seek discretionary denial in almost every, if not every, case. Diverting these APJ resources to a separate discretionary denial process does not appear likely to free up resources to consider the merits of IPR/PGR challenges; rather, it merely moves those resources under the Director’s direct control. The only way the bifurcated process is likely to result in a significant reduction of the PTAB’s workload will be if the new procedure leads to an increase in discretionary denials. Thus, despite the memo’s workload justification, its practical effect will likely be to increase discretionary denials, which will, in turn, reduce the overall institution rate for petitions.

New Discretionary Considerations: Expanded Scope With Little Precedent

The Director’s memorandum also substantially expands the factors that may justify discretionary denial far beyond the established framework. The factors include:

Whether any forum has previously adjudicated the patent claims’ validity.

Post-issuance changes in law or precedent affecting patentability.

The strength of the unpatentability challenge.

The extent of the petition’s reliance on expert testimony.

“Settled expectations” of the parties, including how long the patent has been in force.

Compelling economic, public health, or national security interests.

The PTAB’s workload capacity and ability to meet statutory deadlines.

Unlike the Fintiv, General Plastic, and Advanced Bionics discretionary denial considerations — which developed incrementally through PTAB precedent, with case law citations and regulatory justifications — the new factors appear to be novel and lack traditional statutory or regulatory foundation. This immediate expansion of discretionary considerations with little accompanying commentary leaves practitioners with extremely limited guidance on how these factors will be applied or weighed in practice.

Several considerations may be particularly likely to lead to increased uncertainty. The “settled expectations” factor suggests older patents might be immune from PTAB review based on their age, but the memorandum provides no guidance as to how old a patent needs to be before its validity cannot be subject to IPR. Similarly, the prospect of discretionarily denying a petition because of “the extent of reliance on expert testimony” may make petitioners question whether a detailed, comprehensive expert declaration may counterintuitively lead to denial of the petition. And from an efficiency standpoint, the “strength of the challenge” consideration will require the Director to examine the merits of each petition’s validity grounds, an evaluation which the PTAB merits panel will have to later undertake as well — a potentially inefficient duplication of effort, now built into the process.

Most concerning for stakeholders may be the explicit acknowledgment that the Director may deny institution based solely on PTAB “workload capacity.” If the USPTO begins denying meritorious challenges purely for administrative convenience, this factor risks transforming discretionary denial from a policy-based consideration into a resource management tool. It also may severely diminish the predictability of the Director’s discretionary denial evaluation — it is difficult to see how a prospective petitioner could adequately anticipate the workload demands of the PTAB three to six months in the future, when the Director will be deciding whether to deny a particular petition due to workload capacity.

Immediate Application and Strategic Considerations

The procedures outlined in the Acting Director’s memorandum apply to all IPR and PGR proceedings where the patent owner preliminary response deadline has not yet passed. For cases where the discretionary denial briefing timeline has already elapsed, patent owners have a one-month window from the memo’s date to submit discretionary denial arguments. Practitioners, therefore, must immediately adapt to these changes on behalf of their clients.

Patent owners may wish to capitalize on this shift by attempting creative new discretionary denial arguments that test the limits of the new factors announced by the Director, particularly emphasizing patent age and PTAB workload concerns. Petitioners should carefully evaluate the extent of their reliance on expert testimony and consider challenging the application of any new discretionary denial justifications that are applied without notice. All practitioners should closely monitor early decisions under this framework to identify how the Director weighs these new factors and consider whether alternative forums may now provide more predictable paths for patent challenges.

Finally, it is critical to recognize that decisions whether to institute an IPR or PGR are unappealable, and thus parties will have no opportunity to seek review of the Director’s decision whether to discretionarily deny a petition. Moreover, appellate courts will not have the ability to provide direct feedback to the USPTO on the new discretionary denial doctrines announced in the memorandum. Given that the new bifurcated process and considerations announced by the Acting Director were not the product of traditional notice-and-comment rulemaking as required by the Administrative Procedure Act, this means that the sole opportunity for stakeholders to have a voice in these rapidly developing doctrines is through case-specific briefing during pending IPR or PGR petitions. This context only heightens the importance of strategically developing arguments and counterarguments on discretionary denial under the new briefing process.

While characterized in the memorandum as “temporary,” it is reasonable to expect that these procedures will significantly impact PTAB practice for the foreseeable future. The USPTO has promised a “boardside chat” with PTAB leadership to address implementation questions, which will hopefully provide additional clarity on these sweeping changes. We will continue to monitor the significant changes to the PTAB and provide updates as warranted.

The BR Privacy & Security Download: April 2025

STATE & LOCAL LAWS & REGULATIONS

Virginia Governor Vetoes AI Bill: Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin vetoed the Virginia High-Risk Artificial Intelligence Developer and Deployer Act (the “Act”). The Act was similar to the Colorado AI Act and would have required developers to use reasonable care to prevent algorithmic discrimination and to provide detailed documentation on an AI system’s purpose, limitations, and risk mitigation measures. Deployers of AI systems would have been required to implement risk management policies, conduct impact assessments before deploying high-risk AI systems, disclose AI system use to consumers, and provide opportunities for correction and appeal. The governor stated that the Act’s “rigid framework fails to account for the rapidly evolving and fast-moving nature of the AI industry and puts an especially onerous burden on smaller firms and startups that lack large legal compliance departments” and that the Act “would harm the creation of new jobs, the attraction of new business investment, and the availability of innovative technology” in the state. The governor also noted that existing state laws “protect consumers and place responsibilities on companies relating to discriminatory practices, privacy, data use, libel, and more” and that an executive order issued by the governor in 2024 established safeguards and oversight for AI use.

CPPA Advances Regulations for Data Broker Deletion Mechanism: The California Privacy Protection Agency (“CPPA”) advanced proposed California Delete Act regulations through the establishment of the Delete Request and Opt-Out Platform (“DROP”). These regulations would create an accessible mechanism for consumers to request the deletion of all their non-exempt personal information held by registered data brokers via a single request to the CPPA. The proposed rules also clarify the definition of a “direct relationship” with a consumer, specifying that simply collecting personal information directly from a consumer does not constitute a direct relationship unless the consumer intends to interact with the business. This revision could bring more businesses, such as third-party cookie providers, under the definition of data brokers. Consumers will likely be able to access DROP by January 1, 2026, and data brokers will be required to access it by August 1, 2026.

Virginia Enacts Reproductive Privacy Law: Virginia enacted amendments to the Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act to prohibit the collection, disclosure, sale, or dissemination of consumers’ reproductive or sexual health data without consent. “Reproductive or sexual health information” is defined under the law as “information relating to the past, present, or future reproductive or sexual health of an individual,” including: (1) efforts to research or obtain reproductive or sexual health information services or supplies, including location information that may indicate an attempt to acquire such services or supplies; (2) reproductive or sexual health conditions, status, diseases, or diagnoses, including pregnancy, menstruation, ovulation, ability to conceive a pregnancy, whether an individual is sexually active, and whether an individual is engaging in unprotected sex; (3) reproductive and sexual health-related surgeries and procedures, including termination of a pregnancy; (4) use or purchase of contraceptives, birth control, or other medication related to reproductive health, including abortifacients; (5) bodily functions, vital signs, measurements, or symptoms related to menstruation or pregnancy, including basal temperature, cramps, bodily discharge, or hormone levels; (6) any information about diagnoses or diagnostic testing, treatment, or medications, or the use of any product or service relating to the matters described in 1 through 5; and (7) any information described in 1 through 6 that is derived or extrapolated from non-health-related information such as proxy, derivative, inferred, emergent, or algorithmic data. “Reproductive or sexual health information” does not include protected health information as defined by HIPAA.

Oregon Attorney General Releases Enforcement Report on Oregon’s Consumer Privacy Act: The Oregon Attorney General released a six-month report on the enforcement of Oregon’s comprehensive privacy law, the Consumer Privacy Act (“OCPA”), which took effect on July 1, 2024. The report provides that, as of the beginning of 2025, the Privacy Unit within the Civil Enforcement Division at Oregon’s Department of Justice (“Privacy Unit”) received 110 complaints. Most of these complaints were about online data brokers. In the last six months, the Privacy Unit initiated and closed 21 matters after sending cure notices (the OCPA provides for a 30-day cure period, which sunsets on January 1, 2026) and broader information requests. Some of the most common deficiencies identified were the lack of requisite disclosures or confusing privacy notices (e.g., not listing the OCPA rights or not naming Oregon in “your state rights” section), and lacking or burdensome rights mechanisms (e.g., the lack of a webpage link for consumers to submit opt-out requests).

Utah Becomes First State to Enact Legislation Requiring App Stores to Verify Users’ Ages:Utah has enacted the App Store Accountability Act, which mandates that major app store providers must verify the age of every user in the state. For users under 18, the law requires verifiable parental consent before any app can be downloaded, including free apps, or any in-app purchases can be made. App stores must also confirm a user’s age category (adult, older teen (16-17), younger teen (13-15), or child (under 13)). When a minor creates an account, it must be linked to a parent’s account. App store providers are responsible for building systems to verify ages, obtain parental consent, and share this data with app developers. They must also provide sufficient disclosure to parents about app ratings and content and notify them of significant changes to apps their children use, requiring renewed consent. Violations of the law will be considered deceptive trade practices, and the act creates a private right of action for harmed minors or their parents. The core requirements for age verification and parental consent are set to take effect on May 6, 2026.

Michigan Legislative Committee Advances Judicial Privacy Bill: The Michigan Senate Committee on Civil Rights, Judiciary, and Public Safety provided a favorable recommendation for a judicial privacy bill that would allow state and federal judges to request the deletion of their personal information from public listings. The Michigan bill would create a private right of action with mandatory recovery of legal fees for any entity that fails to respond to a valid deletion request. The purpose of the bill is to protect against a significant uptick in threats against judicial officers and their families. The bill is based on Jersey’s Daniel’s Law, which has sparked a wave of class action lawsuits against data brokers and online listing companies. If passed, businesses that receive a valid request from a member of the judiciary or their immediate family members under the proposed bill would have to remove from publication any covered information pertaining to the requestor.

Virginia Legislature Passes Consumer Data Protection Act Amendments Restricting Minors’ Use of Social Media; Governor Declines to Sign: The Virginia Legislature unanimously passed a bill to amend the Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act to limit minors’ use of social media to one hour per day. Specifically, the bill would require that any social media platform operator to (1) use commercially reasonable methods, such as a neutral age screen mechanism, to determine whether a user is a minor younger than 16 years of age and (2) limit any such minor’s use of such social media platform to one hour per day, per service or application, and allow a parent to give verifiable parental consent to increase or decrease the daily time limit. Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin declined to sign the bill as passed, recommending several changes to strengthen the bill. These recommendations include raising the age of covered users from 16 to 18 and requiring social media platform operators to disable infinite scroll features and auto-playing videos unless the operator has obtained verifiable parental consent.

FEDERAL LAWS & REGULATIONS

Lawmakers Reintroduce COPPA 2.0 to Strengthen Children and Teens’ Online Privacy:U.S. Senators Bill Cassidy (R-LA) and Edward Markey (D-MA) have reintroduced the Children and Teens’ Online Privacy Protection Act (“COPPA 2.0”), aiming to update online data privacy rules to better protect children and teenagers. The bill seeks to address the youth mental health crisis by stopping data practices that contribute to it. COPPA 2.0 proposes several key measures, including a ban on targeted advertising to children and teens and the creation of an “Eraser Button,” allowing users to delete personal information. It also establishes data minimization rules to limit the excessive collection of young people’s data and revises the “actual knowledge” standard to prevent platforms from ignoring children on their sites. Furthermore, the legislation would require internet companies to obtain consent before collecting personal information from users aged 13 to 16. Previous versions of COPPA 2.0 have advanced in Congress, passing the Senate and a House committee in the past.

White House Seeks Stakeholder Input for Trump Administration’s AI Action Plan:The White House Office of Science and Technology Policy issued a Request for Information to gather public input on the administration’s AI Action Plan. This AI Action Plan intends to define priority policy actions to enhance America’s position as an AI powerhouse and prevent unnecessary regulations from hindering private sector innovation. The focus is on promoting U.S. competitiveness in AI, limiting regulatory burdens, and developing safeguards that support responsible AI advancement. Stakeholders, including academia, industry groups, and private sector organizations, were encouraged to share their policy ideas on topics such as model development, cybersecurity, data privacy, regulation, national security, innovation, and international collaboration. The submitted comments will be used to inform future regulatory proposals.

Congresswoman Issues RFI for Input on U.S. Privacy Act Reform: Congresswoman Lori Trahan (D-MA) announced her effort to reform the Privacy Act of 1974, aiming to protect Americans’ data from government abuse. The proposed reforms seek to address outdated provisions in the act and enhance privacy protections for individuals in the digital age. Trahan emphasized the importance of updating the act to reflect modern technological advancements and the increasing amount of personal data collected by government agencies. The initiative includes measures to ensure greater transparency, accountability, and oversight of data collection practices. Trahan highlights the urgency of the issue as a result of access by the Department of Government Efficiency staff to personal data held by several agencies and calls for legislative action to protect citizens’ privacy rights and prevent government overreach.

U.S. LITIGATION

Court Blocks Enforcement of California Age-Appropriate Design Code: Industry group NetChoice scored yet another victory over the California Age-Appropriate Design Code Act, obtaining a second preliminary injunction temporarily blocking its enforcement. The act was passed unanimously by the California legislature in 2022 and—if enforced—would place extensive new requirements on websites and online services that are “likely to be accessed by children” under the age of 18. NetChoice won its first preliminary injunction in September 2023 on the grounds that the act would likely violate the First Amendment. In August 2024, the Ninth Circuit partially upheld this injunction, finding that NetChoice was likely to succeed in demonstrating that the act’s data protection impact assessment provisions violated the First Amendment. However, the Ninth Circuit remanded the case for determination of the constitutionality of the remaining provisions as well as whether any unconstitutional provisions could be severed from the remainder of the act. On remand, Judge Beth Labson Freeman again granted NetChoice’s motion for preliminary injunction finding that the act regulates protected speech, triggering a strict scrutiny review. Judge Freeman concluded that although California has a compelling interest in protecting the privacy and well-being of children, this interest alone is not sufficient to satisfy a strict scrutiny standard. This ruling is likely to strengthen NetChoice’s opposition of similar acts, such as the Maryland Age-Appropriate Design Code Act.

Court Rejects Allegheny Health Network’s Attempt to Force Arbitration over Meta Pixel Tracking:The U.S. District Court for the Western District of Pennsylvania ruled that Allegheny Health Network (“AHN”) cannot compel arbitration in a class action lawsuit filed by a patient under a pseudonym. The patient alleged that AHN unlawfully collected and disclosed his confidential health information to Meta Platforms. AHN initially sought to compel arbitration based on an arbitration provision within their website’s Terms of Service. However, the court denied this motion, finding that the patient did not have actual or constructive notice of the arbitration agreement. The court found that the link to the AHN’s Terms of Service, a “browsewrap” agreement, was not sufficiently conspicuous, as it was located at the bottom of the homepage among numerous other links and in a less visible footer on its “Find a Doctor” page. Additionally, the court found AHN failed to prove the patient had seen the specific Terms of Service containing the arbitration provision that was added to the website.

Supreme Court Declines Review of Sandhills Medical Data Breach Suit:The U.S. Supreme Court has declined to review a Fourth Circuit decision that ruled Sandhills Medical Foundation Inc. (“Sandhills Medical”), a federally funded health center, cannot use federal immunity to shield itself from a data breach lawsuit. The lawsuit was brought by Joann Ford following a data breach at Sandhills Medical. Sandhills Medical argued it was entitled to federal immunity under 42 U.S.C. § 233(a), which protects federally funded health centers from lawsuits related to the performance of medical, surgical, dental, or related functions. The Fourth Circuit, however, interpreted “related functions” narrowly, stating it did not cover data protection. Sandhills Medical, in its petition to the Supreme Court, contended that this ruling created a circuit split with the Ninth and Second Circuits, which have taken a broader view of the immunity. Sandhills Medical warned that the Fourth Circuit’s “unnaturally cramped” reading of the statute needed correction. Despite these arguments, the Supreme Court denied Sandhills Medical’s petition, meaning the health center will now face the lawsuit in South Carolina District Court.

Utah Attorney General Seeks Reinstatement of Utah Minor Protection in Social Media Act: Utah has requested a federal appeals court to reinstate a law that imposes restrictions on social media platforms. The Utah Minor Protection in Social Media Act (the “Act”), passed in 2024, was previously blocked by a lower court. The act aims to protect minors from harmful content and requires social media companies to verify the age of users and obtain parental consent for minors. Utah’s Attorney General argues that the law is necessary to safeguard children from online dangers and prevent exploitation. Previously, tech industry group NetChoice successfully sued to block the law, arguing it infringes on First Amendment rights and imposes undue burdens on businesses.

Court Holds Sharing of IP Address Insufficient to Prove Harm in CIPA Case: Judge Edgardo Ramos of the Southern District of New York granted defendant Insider, Inc.’s (“Insider”) motion to dismiss claims that its use of Audiencerate’s website analytics tools constituted an unlawful ‘pen register’ in violation of California’s Invasion of Privacy Act (“CIPA”). Plaintiffs argued that Insider invaded their privacy when it installed a tracker on their browsers, sending their IP addresses to a third party, Audiencerate, without their consent. However, Judge Ramos found that this collection and disclosure of IP addresses was insufficient to establish harm for purposes of Article III standing. He found that unlike a Facebook ID, which can be used to track or identify specific individuals, an IP address cannot be used to identify an individual and can only provide geographic information “as granular as a zip code.” Therefore, disclosure of an IP address would not be highly offensive to a reasonable person. Judge Ramos further emphasized that this “conclusion is consistent with the general understanding that in the Fourth Amendment context a person has no reasonable expectation of privacy in an IP address.” Despite this ruling, CIPA class actions and demands are likely to remain a constant threat to business with California-facing websites.

Periodical Publisher Unable to Dismiss VPPA Class Action: Judge Lewis J. Liman of the Southern District of New York denied defendant Springer Nature America’s (“Nature”) motion to dismiss claims that its use of Meta Pixel violated the Video Privacy Protection Act (“VPPA”). The VPPA prohibits videotape service providers from knowingly disclosing personally identifiable information about their renters, purchasers, or subscribers. Despite being drafted to address information collected through physical video stores, the VPPA has become a potent tool in the hands of the plaintiffs’ bar to challenge websites containing video content. Although Nature is primarily a research journal publication, Judge Lewis found that it could qualify as a videotape service provider as defined under the VPPA in part because of the video content on its website and its subscription-based business model. Relying on the recent Second Circuit decision in Salazar v. National Basketball Association, Judge Liman also found that the plaintiff had alleged a concrete injury sufficient to confer standing because the disclosure of information about videos viewed was adequately similar to the public disclosure of private facts. This ruling should remind companies whose websites contain significant video content to carefully review their cookie usage and consent management capabilities.

U.S. ENFORCEMENT

CPPA Requires Data Broker to Shut Down: As part of its public investigative sweep of data broker registration compliance, the CPPA reached a settlement agreement with Background Alert, Inc. (“Background Alert”) for failing to register and pay an annual fee as required by California’s Delete Act. The Delete Act requires data brokers to register and pay an annual fee that funds the California Data Broker Registry. As part of the settlement, Background Alert must shut down its operations for three years for failing to register between February 1 and October 8, 2024. If Background Alert violates any term of the settlement, including the requirement to shut down its operations, it must pay a $50,000 fine to the CPPA.

New York Attorney General Settles with App Developer for Failure to Protect Students’ Privacy: The New York Attorney General settled with Saturn Technologies, the developer of the Saturn app, for failing to protect students’ privacy. Saturn allows high school students to create a personal calendar, interact with other users, share social media accounts, and know where other users are located based on their calendars. The New York Attorney General’s investigation found that unlike what Saturn Technologies represented, the company failed to verify users’ school email and age to ensure only high school students from the same high school interacted. The investigation also found that Saturn Technologies used copies of users’ contact books even when the user changed their phone settings to deny Saturn’s access to their contact book. Under the settlement, Saturn Technologies must pay $650,000 in penalties and change its verification process, provide enhanced privacy options for students under 18, and prompt users under 18 to review their privacy settings every six months.

New York Attorney General Sues Insurance Companies for Back-to-Back Data Breaches: The New York Attorney General sued insurance companies National General and Allstate Insurance Company for back-to-back data breaches, which exposed the driver’s license numbers of more than 165,000 New Yorkers. In 2020, attackers took advantage of a flaw on two of National General’s auto insurance quoting websites, which displayed consumers’ full driver’s license numbers in plain text. The complaint alleges that National General failed to detect the breach for two months and failed to notify consumers and the appropriate state agencies. The complaint also alleges that National General continued to leave driver’s license numbers exposed on a different quoting website for independent insurance agents, resulting in another data breach in 2021. This action is the New York Attorney General’s latest effort to hold auto insurance companies accountable for failing to protect consumers’ personal information against an industry-wide campaign by attackers targeting online auto insurance quoting applications.

California Attorney General Announces Investigative Sweep of Location Data Industry: The California Attorney General announced an ongoing investigative sweep into the location data industry. The California Attorney General sent letters to advertising networks, mobile app providers, and data brokers that appear to be in violation of the California Consumer Privacy Act, as amended by the California Privacy Rights Act (“CCPA”). The enforcement sweep is intended to ensure that businesses comply with their obligations under the CCPA with respect to consumers’ rights to opt out of the sale and sharing of personal information and limit the use of sensitive personal information, which includes precise geolocation data. The letters sent by the California Attorney General notify recipients of potential violations of the CCPA and request additional information regarding how the recipients offer and effectuate such CCPA rights. Location data has become an enforcement priority for the California Attorney General given the federal landscape affecting California’s immigrant communities and reproductive and gender-affirming healthcare.

CPPA Settles with Auto Manufacturer for CCPA Violations: The CPPA settled with American Honda Motor Co. (“Honda”) for its alleged CCPA violations. The CPPA alleged that Honda (1) required consumers to verify themselves and provide excessive personal information to exercise their rights to opt out and limit; (2) used an online privacy management tool that failed to offer consumers their CCPA rights in a symmetrical way; (3) made it difficult for consumers to authorize agents to exercise their CCPA rights on their behalf; and (4) shared personal information with ad tech companies without contracts containing CCPA-required language. As part of the settlement, Honda must pay $632,500, implement new and simpler methods for submitting CCPA requests, and consult a user experience designer to evaluate its methods, train its employees, and ensure the requisite contracts are in place with third parties with whom it shares personal information. This action is a part of the CPPA’s investigative sweep of connected vehicle manufacturers and related technologies.

OCR Settles with Healthcare Provider for HIPAA Violations: The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office for Civil Rights (“OCR”) settled with Oregon Health & Science University (“OHSU”) over potential violations of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (“HIPAA”) Privacy Rule’s right of access provisions. The HIPAA Privacy Rule requires covered entities to provide individuals or their personal representatives access to their protected health information within thirty days of a request (with the possibility of a 30-day extension) for a reasonable, cost-based fee. OCR initiated an investigation against OHSU for a second complaint OCR received in January 2021 from the individual’s personal representative. OCR resolved the first complaint in September 2020, when OCR notified OHSU of its potential noncompliance with the Privacy Rule for only providing part of the requested records. However, OHSU did not provide all of the requested records until August 2021. As part of the settlement, OHSU must pay $200,000 in penalties.

Democratic FTC Commissioners Fired by Trump Administration: The Trump administration fired the Federal Trade Commission’s (“FTC”) Democratic Commissioners Alvaro Bedoya and Rebecca Kelly Slaughter. Their removal leaves the FTC with no minority party representation among the agency’s five commissioner bench. Slaughter was originally nominated by Trump in 2018 and was serving her second term. Bedoya was in his first term as commissioner. Bedoya and Slaughter indicated in public statements that they would take legal action to challenge the firings. Among potential privacy impacts of the firings is how the lack of minority party representation may affect the enforcement of the EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework (“DPF”), which is used by many businesses to legally transfer personal data from the EU to the United States. The DPF is intended to be an independent data transfer mechanism, and the removal may heighten concerns about the independence of agencies tasked with enforcing the DPF. The move at the FTC follows the prior removal of democrats from the U.S. Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board, which is charged with providing oversight of the redress mechanism for non-U.S. citizens under the DPF.

CFPB Drops Suit Against TransUnion: The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (“CFPB”) voluntarily dismissed with prejudice its lawsuit against TransUnion in which it alleged that TransUnion engaged in deceptive marketing practices in violation of a 2017 consent order. The CFPB provided no explanation for its decision and each party agreed to bear its own litigation costs and attorneys’ fees.

INTERNATIONAL LAWS & REGULATIONS

CJEU Rules Data Subject Is Entitled to Explanation of Automated Decision Making: The Court of Justice of the European Union (“CJEU”) ruled that a controller must describe the procedure and principles applied in any automated decision-making technology in a way that the data subject can understand what personal data was used, and how it was used, in the automated decision making. The ruling stemmed from an Austrian case where a mobile telephone operator refused to allow a customer to conclude a contract on the ground that her credit standing was insufficient. The operator relied on an assessment of the customer’s credit standing carried out by automated means by Dun & Bradstreet Austria. The court also stated that the mere communication of an algorithm does not constitute a sufficiently concise and intelligible explanation. In order to meet the requirements of transparency and intelligibility, it may be appropriate to inform the data subject of the extent to which a variation in the personal data would have led to a different result. Companies will have to be creative in assessing what information is required to ensure the explainability of automated decision-making to data subjects.

European Parliament Publishes Report on Potential Conflicts Between GDPR and EU AI Act: The European Parliament published a report on the interplay of the EU AI Act with the EU General Data Protection Regulation (“GDPR”). One of the AI Act’s main objectives is to mitigate discrimination and bias in the development, deployment, and use of “high-risk AI systems.” To achieve this, the EU AI Act allows “special categories of personal data” to be processed, based on a set of conditions (e.g., privacy-preserving measures) designed to identify and to avoid discrimination that might occur when using such new technology. The report concludes that the GDPR, which imposes limits on the processing of special categories of personal data, might prove restrictive in the circumstances under which the GDPR allows the processing of special categories of personal data. The paper recommends that GDPR reforms of further guidelines on how the GDPR works with the EU AI Act would help address any conflicts.

Norwegian and Swedish Data Protection Authorities Release FAQs on Personal Data Transfers to United States: The Norwegian and Swedish data protection authorities issued FAQs on Personal Data Transfers to the United States in response to the dismissal of several members of the U.S. Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board (“PCLOB”). The PCLOB is responsible for providing oversight of the redress mechanism for non-U.S. citizens under the U.S.-EU Data Protection Framework (“DPF”), which is one legal mechanism available to transfer EU personal data to the U.S. under the GDPR. Datatilsynet, the Norwegian data protection authority, stated that it understands that the intent is to appoint new PCLOB members in the future and that, even without a quorum, the PCLOB can perform some tasks related to the DPF. Accordingly, Datatilsynet stated that issues would only arise in the adequacy decision underpinning the DPF as a result of the removal of the PCLOB members if the appointment of new members takes a long time. The Swedish data protection authority, Integritetsskydds myndigheten (“IMY”) also cited confusion of the European business community following the dismissal of several members of the PCLOB. The IMY stated that the Court of Justice of the European Union has the authority to annul the DPF adequacy decision but has not taken such action. As a result, the DPF is still a valid mechanism for data transfer according to the IMY. Both data protection authorities indicated they would continue to monitor the situation in the U.S. to determine if anything occurred that affected the DPF and its underlying adequacy decision.

OECD Releases Common Reporting Framework for AI Incidents: The OECD Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (“OECD”) released a paper titled “Towards a Common Reporting Framework for AI Incidents.” The paper outlines the need for a standardized approach to reporting AI-related incidents. It emphasizes the importance of transparency and accountability in AI systems to ensure public trust and safety. The report proposes a framework that includes guidelines for identifying, documenting, and reporting incidents involving AI technologies. The paper specifically identifies 88 potential criteria for a common AI incident reporting framework across 8 dimensions. The 8 dimensions are (1) incident metadata, such as date of occurrence, title, and description of the incident; (2) harm details focusing on severity, type, and impact; (3) people and planet, describing impacted stakeholders and associated AI principles; (4) economic context describing the economic sectors where the AI was deployed; (5) data and input, which includes a description of the inputs selected to train the AI system; (6) AI model providing information related to the model type; (7) task and output, describing the AI system tasks, automation level, and outputs; and (8) other information about the incident to catch any complementary information reported with respect to an incident.

China Issues Draft Measures for Financial Institutions to Report Cybersecurity Incidents and for Data Compliance Audits: The People’s Bank of China (“PBOC”) released draft administrative measures for reporting cybersecurity incidents in the financial sector (“Draft Measures”). The Draft Measures provide guidelines for identifying, reporting, and managing cybersecurity incidents by financial institutions regulated by the PBOC. Reporting requirements and timing vary according to type of entity and classification of incidents. Incidents would be classified as one of four categories – especially significant, significant, large, and average. Separately, the Cyberspace Administration of China (“CAC”) issued administrative measures on data protection audit requirements (“Data Protection Audit Measures”). The Data Protection Audit Measures provide (1) the conditions under which an audit of a data handler’s compliance with relevant personal information protection legal requirements would be required; (2) selection of third-party compliance auditors; (3) frequency of compliance audits; and (4) obligations of data handlers and third-party auditors in conducting compliance audits. The Data Protection Audit Measures include guidelines setting forth the specific factors that data handlers must evaluate in an audit, including the legal basis for processing personal information, whether the data handler has complied with notice obligations, how personal information is transferred outside of China, and the technical security measures employed by the data handler to protect personal information, among other factors.

European Commission Releases Third Draft of General-Purpose AI Code of Practice: The European Commission announced the publication of the third draft of the EU General-Purpose AI Code (“Code”). The first two sections of the draft Code detail transparency and copyright obligations for all providers of general-purpose AI models, with notable exemptions from the transparency obligations for providers of certain open-source models in line with the AI Act. The third section of the Code is only relevant for a small number of providers of most advanced general-purpose AI models that could pose systemic risks, in accordance with the classification criteria in Article 51 of the AI Act. In the third section, the Code outlines measures for systemic risk assessment and mitigation, including model evaluations, incident reporting, and cybersecurity obligations. A final version of the General-Purpose AI Code of Practice is due to be presented and published to the European Commission in May.

Additional Authors: Daniel R. Saeedi, Rachel L. Schaller, Gabrielle N. Ganze, Ana Tagvoryan, P. Gavin Eastgate, Timothy W. Dickens, Jason C. Hirsch, Adam J. Landy, Amanda M. Noonan and Karen H. Shin.

DEFENSE WIN: Court Dismisses TCPA Class Action – Recruitment Calls Are Not “Telephone Solicitations”

Hey TCPAWorld!

TCPA litigation is on the rise, with plaintiffs’ attorneys often trying to target companies that aren’t actually engaged in telemarketing. But not this time, the Court got it right and Defendant walked away with a Win (for now at least).

We have an exciting and interesting case out of the Western District of New York where the Court granted Defendant’s Motion to Dismiss finding that the calls made by Medicus Healthcare Solutions, LLC (“Medicus”) were not in violation of the Telephone Consumer Protection Act of 1991 (TCPA). Rockwell v. Medicus Healthcare Solutions, 2025 WL 959745 (W.D.N.Y. Mar. 31, 2025).

Plaintiff Rockwell, a physician, alleged that Medicus made multiple unwanted calls to him in 2023 regarding temporary physician placement opportunities. Rockwell, who was registered on the national Do Not Call Registry, received four calls from Medicus offering locum tenens opportunities and other professional services. Despite requesting that the calls stop, he claims that he continued to receive them.

According to his complaint, Rockwell claims that these calls violated the TCPA, which prohibits multiple unsolicited calls to a number on the Do Not Call Registry within a 12-month period and the TCPA implementing regulations, including “No person or entity shall initiate any telephone solicitation to…[a] residential telephone subscriber who has registered his or her telephone number on the national do not-call registry of persons who do not wish to receive telephone solicitations that is maintained by the federal government.” 47 C.F.R. § 64.1200(c)(2).“Telephone solicitation” is defined as “the initiation of a telephone call or message for the purpose of encouraging the purchase or rental of, or investment in, property, goods, or services.” 47 U.S.C. § 227(a)(4); 47 C.F.R. § 64.1200(f)(15).

But Medicus correctly argued that the calls were not “telephone solicitations” because they were recruiting calls, not calls to sell or market a product or service. Defendant contended that simply informing Rockwell of job opportunities did not encourage the purchase, rental, or investment in property, goods, or services. Exactly!

The Court noted that several district courts have concluded that communications sent for the purpose of job recruitment do not constitute telemarketing or telephone solicitations and ultimately, sided with Medicus, citing the case of Gerrard v. Acara Solutions, Inc., where recruitment calls were found not to violate the TCPA. The Court emphasized that Medicus’s calls were not made to sell anything to Rockwell; instead, they were designed to recruit physicians for staffing opportunities, which does not fall under the definition of “telemarketing” or “telephone solicitation” under the TCPA.

The Court also noted that Rockwell did not allege that Medicus would receive payment for the professional services provided to him or that any of those services were intended to generate revenue from him.

“It is possible that an individual client like Rockwell would pay a fee if he accepted Medicus’s placement for professional services or have a portion of his eventual income earmarked to cover those services. But it is equally possible that Medicus receives no payment for these services and simply uses them as a tool to ensure it has qualified candidates to place with its corporate clients seeking short-term staffing. In the absence of any allegations about the workings of Medicus’s business model and the role that its professional services play in that business model, this Court cannot conclude that the telephone calls Rockwell received constituted “telemarketing” or “telephone solicitation” under the TCPA and its implementing regulations.”

Without this critical element, the Court could not conclude that the calls constituted a violation of the TCPA. As a result, the Court granted Medicus’s Motion to Dismiss the complaint, dismissing it without prejudice. Rockwell was given 30 days to amend his complaint to address any deficiencies identified by the Court.

This ruling underscores that recruitment calls—without the element of selling goods or services—do not violate the TCPA.

Til next time!!!

TWICE AS BAD: Choice Home Warranty Suffers Massive TCPA Loss That Opens the Door to Double Dipping

The TCPA is bad enough without Plaintiffs being able to recover twice under the statute’s abusive provisions for a single phone call or text. But that is exactly what just happened in New Jersey with Choice Home Warranty losing a motion to dismiss a double dip effort by a number of individual TCPA litigators.

In Jubb v. CHW, 2025 WL 942961 (D. N.J. March 28, 2025) the Plaintiffs each alleged several calls from CHW that allegedly were made without consent in violation of the TCPA’s DNC provisions.

CHW moved to dismiss on several grounds asserting the complaint did not either directly or indirectly link the calls back to it, but the court completely disagreed and found the complaint adequately alleged both direct and vicarious liability.

This is bad enough but the Court also refused to dismiss the Plaintiff’s time restriction claim–i.e. that the calls had been made before 8 am or after 9 pm–even though they plaintiffs were separately suing for those same calls under a basic DNC violation theory.

In other words, the court just allowed the plaintiffs to double dip and recover twice under 227(c) for a single call.

Not good. This is especially true given the massive onslaught of time restriction TCPA class actions that have been filed as of late.

So big loss for CHW and now, potentially, the industry.

Class Action Litigation Newsletter | 4th Quarter 2024

This GT Newsletter summarizes recent class-action decisions from across the United States.

Highlights from this issue include:

First Circuit addresses four questions of first impression relating to CAFA jurisdiction and “home state” and “local controversy” exceptions.

Second Circuit holds class representative’s susceptibility to unique defenses is not a basis for finding lack of adequacy, though it may go to typicality.

Fourth Circuit reverses certification of FLSA class action, finding conclusory allegations of company policies were insufficient to satisfy commonality requirement.

Sixth Circuit vacates class certification based on individualized questions in automotive defect case.

Seventh Circuit affirms decertification of Rule 23(c)(4) issues class for lack of superiority.

Ninth Circuit holds unexecuted damages model sufficient to demonstrate damages are susceptible to common proof at the class certification stage.

Continue reading the full GT Class Action Litigation Newsletter | 4th Quarter 2024

Additional Authors: Richard Tabura, Aaron Van Nostrand, Gregory A. Nylen, David G. Thomas, Angela C. Bunnell, R. Morgan Carpenter, Gina Faldetta, and Gregory Franklin.

Yes, Damages for Delay: Court Permits Delay Damage Claim to Proceed

A federal court in upstate New York is permitting a subcontractor’s delay claim to proceed notwithstanding a “no damages for delay” provision in the subcontract. The case, The Pike Company, Inc. v. Tri-Krete, Ltd., involves delay claims asserted by a subcontractor hired to install pre-cast concrete walls on a college dormitory project. The subcontractor alleges that the general contractor, The Pike Company, actively interfered with its work causing it to incur costs to overcome that interference and mitigate delays. Pike moved for summary judgment based on the no damages for delay provision in the subcontract, which generally provided that (1) the subcontractor’s only remedy for delays caused by an act or omission of the contractor was an extension of the schedule and (2) any damages for delay, interference, or changes in sequence were waived.

The court held that while such clauses are generally valid and enforceable, there are a number of recognized exceptions:

Yet there are exceptions to the general enforceability of a no damages for delay provision. Even when a contract includes such a provision, damages may be recovered for: (1) delays caused by the contractee’s bad faith or its willful, malicious, or grossly negligent conduct, (2) uncontemplated delays, (3) delays so unreasonable that they constitute an intentional abandonment of the contract by the contractee, and (4) delays resulting from the contractee’s breach of a fundamental obligation of the contract. For example, the failure of a contractor to supervise and coordinate the work of subcontractors on a construction site may preclude the enforcement of a no damages for delay provision. Likewise, a no damages for delay provision may be found to be unenforceable where there is an “intentional abandonment” of the contract that renders it unenforceable—such as when an owner makes dramatic changes to the work or causes significant delay. As the party seeking to preclude the enforcement of the no damages for delay provision, [the subcontractor] bears the “heavy burden” of demonstrating that the provision does not apply.

Applying this law to the facts at hand, the court held that evidence in the record supported a finding that one or more of these exceptions applied. This included evidence that Pike interfered with the subcontractor’s means and method of production, failed to timely complete predecessor work, compressed the subcontractor’s schedule by a factor of 50%, and refused to grant time extensions as provided for in the subcontract. Such evidence of uncontemplated and unreasonable delays caused by Pike, and Pike’s breach of its fundamental subcontract obligations, precluded summary judgment in Pike’s favor.

The court also rejected Pike’s argument that the subcontractor failed to give adequate written notice of its delay claims. The court held that under New York law, oral directives may sustain a claim for extra work damages notwithstanding a contractual provision requiring written authorization. The court further held that Pike arguably waived the written notice requirement when it granted change orders to another contractor on the same job without insisting on written notice. The issues created genuine issues of material fact that precluded summary judgment in Pike’s favor.

A copy of the court’s decision can be found here. No trial date has been set.

Listen To This Article

Fintiv Guidelines for Post-Grant Proceedings Involving Parallel District Court Litigation

On March 24, 2025, the US Patent & Trademark Office (PTO) released new guidance that clarifies application of the Fintiv factors when reviewing validity challenges simultaneously asserted at the Patent Trial & Appeal Board and in district court or at the US International Trade Commission.

This guidance follows the PTO’s February 28, 2025, announcement reverting to its previous guidelines for discretionary denials of petitions for post-grant proceedings where district court litigation is ongoing. That announcement rescinded the PTO’s June 21, 2022, memorandum entitled “Interim Procedure for Discretionary Denials in AIA Post-Grant Proceedings with Parallel District Court Litigation,” which prevented the Board from rejecting validity challenges where there was “compelling evidence of unpatentability.”

Based on the new guidance, the Board is more likely to defer to the district court or the Commission if the Commission’s projected final determination date is earlier than the deadline for the Board’s final written decision. The PTO pointed out that a patent challenger’s stipulation not to raise the same invalidity arguments in other proceedings if the PTO institutes an inter partes review or post grant review is highly relevant but not dispositive.

This change in policy increases the likelihood that the Board will grant discretionary denials in situations involving parallel district court or Commission proceedings.

Impermissible Convoyed Sales Wash Away Damages Award

The US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit affirmed a district court’s finding of infringement but vacated its damages award because the award improperly included auxiliary products lacking any functional relationship to the infringed patent claim. Wash World Inc. v. Belanger Inc., Case No. 2023-1841 (Fed. Cir. Mar. 24, 2025) (Stark, Lourie, Prost, JJ.)

Belanger owns a patent related to a spray-type car wash system. A competitor, Wash World, filed for a declaratory judgment that its car wash system did not infringe the patent.

A jury returned a general verdict of infringement and awarded Belanger $9.8 million in lost profit damages. Wash World moved for judgment as a matter of law of noni nfringement based on the positions it previously raised and challenged the damages award. Wash World argued that Belanger failed to prove entitlement to lost profits for convoyed sales. The district court rejected Wash World’s arguments. Wash World appealed, challenging the district court’s constructions of three claim terms that Wash World argued were dispositive to noninfringement and the damages award for improperly including nearly $2.6 million in ineligible convoyed sales.

The Federal Circuit concluded that for two of the three claim terms, the constructions Wash World argued for on appeal were materially different from the constructions it urged the district court to adopt. The Federal Circuit emphasized that while a party is not confined to the precise wording of the constructions it advances at the district court, it must still present essentially the same dispute on appeal. Finding no exceptional circumstances, the Court deemed Wash World’s appellate positions on the two claims to be forfeited. As to the remaining term, the Court found that while Wash World had preserved the issue for appeal, the district court’s interpretation was correct.

On the issue of remittitur, the Federal Circuit first found that Wash World had properly preserved the issue for appeal and that even if it had not, exceptional circumstances would justify reaching the merits. The Court stated that it could discern the precise damages the jury awarded based on convoyed sales, and that the requirements for lost profits on such sales were plainly not satisfied.

The Federal Circuit explained that entitlement to lost profits for convoyed sales exists only where the unpatented products (e.g., dryers sold together with a patented car wash system) and the patented product together constitute a “functional unit,” like parts of a complete machine. The Court found that no evidence in the record could support such a finding and that damages awarded for sales of the unpatented products were thus improper. The Court further rejected Belanger’s argument that the jury’s return of a general verdict insulated the award from further scrutiny. The Court noted that based on the evidence presented, it was overwhelmingly likely that the jury’s verdict included the impermissible damages for convoyed sales. Therefore, the Federal Circuit instructed the district court on remand to remit $2.6 million in damages corresponding to sales of the unpatented components.

When Analyzing Likelihood of Confusion, It’s Not Just Location, Location, Location

The US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit vacated a district court’s decision finding no infringement that focused on only the geographic distance between the physical locations of the two users without considering the factors bearing on any likelihood of confusion. Westmont Living, Inc. v. Retirement Unlimited, Inc., et al., Case No. 23-2248 (4th Cir. Mar. 18, 2025) (Niemeyer, Benjamin, Berner, JJ.)

Westmont Living, a California corporation that operates several retirement communities and assisted living facilities on the West Coast, sued Retirement Unlimited, a Virginia corporation that operates retirement communities and assisted living facilities on the East Coast, for trademark infringement. Westmont, which operates and markets its facilities using the mark WESTMONT LIVING, alleged that Retirement opened a new facility using the name The Westmont at Short Pump for services identical to those provided by Westmont.

The district court entered summary judgment for Retirement. The district court acknowledged that many factors are potentially relevant to determining the likelihood of confusion, but it concluded that because the parties’ physical facilities were located “in entirely distinct geographic markets,” as a matter of law “consumer confusion [was] impossible.” The district court based its holding on the Second Circuit’s 1959 decision in Dawn Donut v. Hart’s Food Stores, which held that when parties use their marks in separate and distinct markets, there can be no likelihood of confusion. Westmont appealed.

The Fourth Circuit found that the district court failed to address the parties’ competitive marketing, the locations from which they solicit and draw their customers, the scope of their reputations, and any of the nine factors for determining likelihood of confusion in the Fourth Circuit under its 2021 decision in RXD Media v. IP Application Dev. The Court explained that while not every factor necessarily needs to be considered in the analysis, the district court erred by relying solely on the fact that the parties’ physical facilities were on opposite coasts, without considering the many other factors that might bear on whether Westmont had shown a likelihood of confusion.

The Fourth Circuit disagreed with the district court’s reliance on Dawn Donut, explaining that the case stands for a narrow principle that where businesses use the same mark in physically distinct geographical markets, and their marketing and advertising are confined to those markets, there won’t be a likelihood of confusion. Given increased potential customer mobility, the internet, and the reduced influence of local radio and newspaper advertising, it is far less likely today that two businesses would operate in such physically distinct geographical markets as when the Dawn Donut rule was promulgated. In this case, both parties advertised nationwide on the internet. The Court noted that it may be especially difficult for a casual consumer to distinguish between the two companies when engaging in online research about retirement living, and the physical distance of the parties’ facilities does not eliminate that risk. The Fourth Circuit concluded that the district court’s reliance on only the geographic distance between the physical facilities of the two companies was simply too narrow an approach and remanded for further proceedings to consider all relevant factors for determining likelihood of confusion.

Crafting Composition Claims: Federal Circuit Reverses ITC on Diamond Polycrystalline Diamond Compact Patent Eligibility

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit recently reversed an International Trade Commission decision that found certain composition claims for a polycrystalline diamond compact patent ineligible

This ruling provides valuable insights for companies drafting composition of matter claims in materials science, particularly when the claims involve measurable properties that reflect material structure

Companies drafting composition of matter claims should define a specific, non-natural material with measurable parameters, provide detailed specification support for enablement, and link measurable properties to structural features

In a significant decision for the materials science and patent law communities, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit has overturned a ruling by the International Trade Commission (ITC) that found certain claims of a polycrystalline diamond compact (PDC) patent ineligible under U.S. patent laws. The case, US Synthetic Corp. v. International Trade Commission, decided on Feb. 13, 2025, offers important guidance on the patentability of composition of matter claims involving measurements of natural properties.

US Synthetic Corp. (USS) filed a complaint with the ITC alleging violations of customs laws known as Section 337 based on the importation and sale of products infringing its U.S. Patent No. 10,508,502 (‘502 patent), titled “Polycrystalline Diamond Compact.”

A PDC includes a polycrystalline diamond table bonded to a substrate, typically made from a cemented hard metal composite like cobalt-cemented tungsten carbide. PDCs are manufactured using high-pressure, high-temperature (HPHT) conditions. The process involves placing a substrate into a container with diamond particles positioned adjacent to it. Under HPHT conditions and in the presence of a catalyst (often a metal-solvent catalyst like cobalt), the diamond particles bond together to form a matrix of bonded diamond grains, creating the diamond table that bonds to the substrate.

The ‘502 patent describes several key properties of the PDC. It exhibits a high degree of diamond-to-diamond bonding and a reduced amount of metal catalyst without requiring leaching. The PDC’s magnetic properties reflect its composition, including coercivity, specific magnetic saturation, and permeability.

The patent discloses that USS developed a manufacturing method using heightened sintering pressure (at least about 7.8 GPa) and temperature (about 1400°C) to achieve these properties without resorting to leaching, which can be time-consuming and may decrease the mechanical strength of the diamond table.

ITC’s Initial Determination

The ITC initially found the asserted claims infringed and not invalid under Sections 102, 103, or 112 of U.S. patent laws. However, it determined they were patent ineligible under Section 101, preventing a finding of a Section 337 violation. Specifically, the ITC concluded the asserted claims were directed to the “abstract idea of PDCs that achieve . . . desired magnetic . . . results, which the specifications posit may be derived from enhanced diamond-to-diamond bonding,” and that the magnetic properties are merely side effects of the unclaimed manufacturing process.

Federal Circuit’s Analysis

The Federal Circuit focused its analysis on claim 1 and 2 of the ‘502 patent. Claim 1 recited, “a polycrystalline diamond table, at least an unleached portion of the polycrystalline diamond table including: a plurality of diamond grains bonded together via diamond-to-diamond bonding … a catalyst including cobalt … wherein the unleached portion of the polycrystalline diamond table exhibits a coercivity of about 115 Oe to about 250 Oe; wherein the unleached portion of the polycrystalline diamond table exhibits a specific permeability less than about 0.10 G∙cm3/g∙Oe.” Claim 2, depending from claim 1, further recited, “wherein the unleached portion of the polycrystalline diamond table exhibits a specific magnetic saturation of about 15 G∙cm3/g or less.”

The court emphasized that the claims were directed to a composition of matter, not a method of manufacture. It noted that USS had developed a way to produce PDCs with high diamond-to-diamond bonding and reduced metal catalyst content without leaching, addressing known issues in the field.

The Federal Circuit delved deeper into the relationship between the claimed magnetic properties and the structure of the PDC. The court recognized that coercivity, specific magnetic saturation, and specific permeability provide information about the quantity of metal catalyst present and the extent of diamond-to-diamond bonding, which were key features of the inventive PDC. As the court summarized, “Each of these magnetic properties provides information about the quantity of metal catalyst present in the diamond table and/or the extent of diamond-to-diamond bonding.”

The court also highlighted the importance of the specification’s disclosure, which included comparative data between the claimed PDCs and conventional PDCs. This data demonstrated that the claimed PDCs exhibited significantly less cobalt content and a lower mean free path between diamond grains than prior art examples. The court recognized that the prior art examples “exhibit a lower coercivity indicative of a greater mean free path between diamond grains and thus may indicate relatively less diamond-to-diamond bonding between the diamond grains.”

The Federal Circuit engaged in the two-step analysis established by Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank International. Applying Alice step No. 1, the court determined that the claims were directed to a specific composition of matter having particular characteristics, rather than being directed to an abstract idea and did not reach Alice step No. 2. The court found that, in view of the recitation of “a polycrystalline diamond table, at least an unleached portion of the polycrystalline diamond table,” a “plurality of diamond grains,” a “catalyst including cobalt,” and the limitations of magnetic properties, dimensional parameters, and the interface topography between the polycrystalline diamond table and substrate, the claims are plainly directed to matter.

In so holding, the court found the ITC erred when it concluded that the asserted claims are directed to the “abstract idea of PDCs that achieve . . . desired magnetic . . . results, which the specifications posit may be derived from enhanced diamond-to-diamond bonding.” The court also disagreed with the commission’s apparent expectations for precision between the claimed properties and structural details of the claimed composition. As the court noted, a perfect proxy is not required between the recited material properties and the PDC structure.

The court also affirmed the ITC’s finding that the claims were enabled under Section 112, indicating that the specification provided sufficient information for a person of ordinary skill to make and use the invention without undue experimentation. This determination was based on the detailed manufacturing methods and examples provided in the patent specification.

Takeaways

This decision provides valuable guidance for patent practitioners in the materials science field and reinforces the importance of carefully crafting claims and specifications to withstand Section 101 challenges. Composition of matter claims can remain patent-eligible under Section 101 even when they involve measuring natural properties, as long as they claim a non-naturally occurring composition.

When drafting claims for materials science inventions, practitioners should consider including specific, measurable parameters that distinguish the invention from naturally occurring substances or prior art.

The decision also highlights the importance of providing detailed descriptions in the specifications of how to measure claimed properties and how they relate to the composition’s structure or function.

Detour Ahead: New Approach to Assessing Prior Art Rejections Under § 102(e)

The US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit established a more demanding test for determining whether a published patent application claiming priority to a provisional application is considered prior art under pre-America Invents Act (AIA) 35 U.S.C. § 102(e) as of the provisional filing date, explaining that all portions of the published patent application that are relied upon by the US Patent & Trademark Office (PTO) to reject the claims must be sufficiently supported in the provisional application. In re Riggs, Case No. 22-1945 (Fed. Cir. Mar. 24, 2025) (Moore, Stoll, Cunningham, JJ.)

Several inventors who work for Odyssey Logistics filed a patent application directed to logistics systems and methods for the transportation of goods from various shippers by various carriers across different modes of transport (e.g., by rail, truck, ship, or air). PTO rejected the application under § 102(e) in view of Lettich, which claimed the benefit of a provisional application (Lettich provisional), and as obvious in view of Lettich in combination with the Rojek reference.

The inventors appealed the Lettich rejections to the Patent Trial & Appeal Board, arguing that Lettich did not qualify as prior art under § 102(e). The Board initially agreed with the inventors, but the Examiner assigned to the application requested a rehearing, asserting that the Board applied the incorrect standard for § 102(e) prior art. The Board ultimately issued its decision on the Request for Rehearing, stating that it had jurisdiction over the Examiner’s request and that the Examiner’s arguments regarding Lettich’s status as prior art under § 102(e) “[we]re well taken.” The Board amended its original decision “to determine that Lettich is proper prior art against the instant claims.” The Board then reviewed and affirmed the Examiner’s anticipation and obviousness rejections. The inventors appealed.

The Federal Circuit vacated and remanded the Board’s decision. With respect to whether Lettich qualified as § 102(e) prior art, the Court found that the Board’s analysis was incomplete. The Court concluded that the Board correctly applied the test set forth in the Federal Circuit’s 2015 decision in Dynamic Drinkware v. National Graphics by determining that the Lettich provisional supported at least one of Lettich’s as-published claims. However, the Court found that this test was insufficient because all portions of the disclosure that are relied upon by the PTO to reject the claims must also be sufficiently supported in the priority document. Although the PTO asserted that the Board had conducted this additional analysis, the Federal Circuit disagreed and vacated and remanded for the Board to determine whether the Lettich provisional supported the entirety of the Lettich disclosure that the Examiner relied on in rejecting the claims.

Court Sides with RICO Complainant Who Received Tainted Medical Marijuana and with FDA on Regulating E-Cigarettes – SCOTUS Today

The Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO) allows any person “injured in his business or property by reason of” racketeering activity to bring a civil suit for damages. 18 U. S. C. §1964(c). However, the statute forbids suits based on “personal injuries.” But are economic harms resulting from personal injuries “injuries to ‘business or property?’”

Yesterday, in Medical Marijuana, Inc. v. Horn, the U.S. Supreme Court, in a 5–4 opinion written by Justice Barrett and joined by Justices Kagan, Sotomayor, Gorsuch, and Jackson, answered that question in the affirmative. Justices Thomas and Kavanaugh wrote dissenting opinions, the latter joined by the Chief Justice and Justice Alito.

Attempting to alleviate his chronic pain, Douglas Horn purchased and began taking “Dixie X,” advertised as a tetrahydrocannabinol-free (“THC-free”), non-psychoactive cannabidiol tincture produced by Medical Marijuana, Inc. However, when his employer later subjected him to a random drug test, Horn tested positive for THC. When Horn refused to participate in a substance abuse program, he was fired. Horn then brought his RICO suit.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, reversing the U.S. District Court for the Western District of New York, held that Horn had been “injured in his business” when he lost his job and rejecting the “antecedent-personal-injury bar,” which several circuits had adopted to exclude business or property losses that derive from a personal injury. Affirming the Second Circuit, the Supreme Court held that the civil RICO statute did not categorically bar that form of recovery.

Interestingly (and the subject of the dissents, particularly that of Justice Thomas, who asserted that cert. had been improvidently granted), the Court did not address issues deemed outside of the question presented, including whether Horn suffered a personal injury when he consumed THC, whether the term “business” encompasses all aspects of “employment,” and what “injured in his . . . property” means for purposes of §1964(c). Thus, the majority opinion encompasses several assumptions, the verification of which will be the subject of the Court’s ultimate remand to the Second Circuit.

The essence of the opinion is derived from the dictionary, and a debate over how its definitions should be read informs the split among the Justices. Justice Barrett’s majority opinion starts with the American Heritage Dictionary and the “ordinary meaning of ‘injure’”: to “cause harm or damage to” or to “hurt.” While the statute precludes recovery for injury to the person, its business or property requirement operates with respect to the kinds of harm for which the plaintiff can recover, not the cause of the harm for which he seeks relief. For example, a gas station owner beaten in a robbery cannot recover for his pain and suffering. But if injuries from the robbery force him to shut his doors, he can recover for the loss of his business. A plaintiff can seek damages for business or property loss, in other words, regardless of whether the loss resulted from a personal injury.

Rejecting Medical Marijuana’s (and the dissenters’) view of what “business or property” should mean under RICO, Justice Barrett, in a delightfully written paragraph, remarks that:

Medical Marijuana tries valiantly to engineer a rule that yields its preferred outcomes. (Civil RICO should permit suit against Tony Soprano, but not against an ordinary tortfeasor.) But its textual hook—the word “injured”—does not give it enough to go on. When all is said and done, Medical Marijuana is left fighting the most natural interpretation of the text—that “injured” means “harmed”—with no plausible alternative in hand. That is a battle it cannot win.

It didn’t.