A Clearly Rattled Delaware Contemplates Significant Changes To Its Corporations Code

On Monday, Delaware State Senator Bryan Townsend introduced Senate Bill 21 which would, among other things, statutorily define “controlling stockholder” and substantially change the rules governing the “cleansing” of controlling stockholder transactions. Professor Ann Lipton provides a summary of these changes here and Professor Stephen Bainbridge provides his own take on the amendments here. Among other things, Professor Lipton observes:

Collectively, the changes represent a wholesale repudiation of Delaware’s common law approach to lawmaking; instead, they most closely resemble the MBCA’s rule-bound approach.

Actually, I believe that Delaware is moving in the direction of Nevada’s statutory based approach whereby the rules of the road are established primarily by the legislature and not the courts. In fact, this is often cited as a reason to reincorporate in Nevada:

After considering various alternatives, the evaluation committee concluded that Nevada’s statute-focused approach would likely foster more predictability than Delaware’s less predictable common law approach, and that that predictability could be a competitive advantage for the Company in a time of rapid business transformation.

Information Statement filed by Dropbox, Inc. on February 10, 2025.

I do disagree with both Professor Lipton and Dropbox insofar as they characterize Delaware as having a “common law approach”. A distinctive feature of the Court of Chancery is that it is a court of equity, something relatively rare in jurisprudence. A court of equity is results oriented because it is focused on “doing equity”. In fact, this has been the historical understanding that equity (ἐπιεικές*) serves as a correction (ἐπανόρθωμα) of the law. Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics Book V, Section 10. Thus, it has been my own view that while the Court of Chancery has been an historical draw for Delaware, the Court’s broad power to do equity is ultimately proving to undermine Delaware’s preeminence. SB 21 and the Delaware legislature’s assertion of statutory law implicitly recognize this fact.

New York Proposes Expansion of Disclosure Requirements for Material Health Care Transactions

Governor Kathy Hochul released the proposed Fiscal Year 2026 New York State Executive Budget on January 21, 2025 (FY 26 Executive Budget). The FY 26 Executive Budget contains an amendment to Article 45-A of New York’s Public Health Law (hereinafter, the Disclosure of Material Transactions Law), which has been in effect since August 1, 2023. The law currently requires parties to a “material transaction” to provide 30 days pre-closing as well as post-closing notice to the New York State Department of Health (DOH). Since the law has taken effect, DOH has received notice of 9 material transactions, the details of which are listed on its website. If enacted, the amendment will change the reporting parties’ notice requirement, extend waiting periods, and increase DOH’s oversight of material health care transactions.

Existing Pre-Closing Notice Requirements

The Disclosure of Material Transactions Law currently requires a written notice to be submitted to DOH at least 30 days prior to the proposed material transaction’s closing. A transaction will be considered “material” if any of the below occur, whether in a single transaction or through a series of related transactions during a rolling 12-month period that results in a health care entity increasing its gross in-state revenues by $25 million or more:

A merger with a health care entity;

An acquisition of one or more health care entities, including, but not limited to, the assignment, sale, or other conveyance of assets, voting securities, membership, or partnership interest or the transfer of control (which is presumed if any person, directly or indirectly, owns, controls, or holds with the power to vote, 10% or more of the voting securities of a health care entity);

An affiliation or contract formed between a health care entity and another person; or

The formation of a partnership, joint venture, accountable care organization, parent organization, or management service organization for the purpose of administering contracts with health plans, third-party administrators, pharmacy benefit managers, or health care providers.

The law requires all “health care entities”, defined under Article 45-A of New York’s Public Health Law to include physician practices or groups, management services organizations or similar entities that provide all or substantially all administrative or management services under contract with at least one physician practice, provider-sponsored organizations, health insurance plans, and any other health care facilities, organizations, or plans that provide health care services in New York (except for insurers or pharmacy benefit managers regulated by the New York State Department of Financial Services), to submit the notice to DOH. Such notice must include:

The names of the parties to the transaction and their current addresses;

Copies of any definitive agreements governing the terms of the material transaction, including pre- and post-closing conditions;

Identification of all locations where each party provides health care services and the revenue generated in the state from such locations;

Any plans to reduce or eliminate services and/or participation in specific plan networks;

The closing date of the transaction;

A brief description of the nature and purpose of the proposed transaction;

The anticipated impact of the material transaction on cost, quality, access, health equity, and competition in the markets the transaction will impact, which may be supported by data and a formal market impact analysis; and

Any commitments by the health care entity to address anticipated impacts.

Change to Pre-Closing Notice Requirement

The proposed amendment to the Disclosure of Material Transaction Law would modify the timing and content requirements of the required notice to DOH. First, the written pre-closing notice would need to be submitted to DOH at least 60 days prior to the closing of the proposed transaction, as opposed to 30 days under the current law. Second, the written pre-closing notice would require:

A statement as to whether any party to the transaction, or a controlling person or parent company of such party, owns any other health care entity which, in the past three years has closed operations, is in the process of closing operations, or has experienced a substantial reduction in services; and if so,

A statement as to whether a sale-leaseback agreement, mortgage, lease payments, or other payments associated with real estate are a component of the proposed transaction. If so, the parties shall provide the proposed sale-leaseback agreement or mortgage, lease, or real estate documents with the notice.

DOH Preliminary Review

When the Disclosure of Material Transactions Law was initially proposed in the Fiscal Year 2024 Executive Budget (FY 24 Executive Budget), it included not only the notification requirement but also a DOH approval process. Under the FY 24 Executive Budget proposal, each material transaction would be subject to DOH review and approval, including DOH’s consideration of several factors (Review Factors), such as:

If the potential positive impacts of the transaction outweigh any potential negative impacts;

Potential anticompetitive effects of the transaction;

The parties’ financial conditions;

The character and competence of the parties, their officers, and their directors;

The source of funds or assets involved in the transaction; and

The fairness of the exchange.

The amendment to the Disclosure of Material Transactions Law proposed in the FY 26 Executive Budget does not revive the Review Factors. However, it does provide that DOH shall conduct a preliminary review of all proposed transactions and, at its discretion, conduct a full cost and market impact review of the transaction. DOH shall notify the parties of the date the preliminary review is completed, and if DOH requires a full cost and market impact review, it shall notify the parties that such a review is required. The law does not specify a timeframe by which DOH must complete its preliminary review. However, if a full cost and market impact review is required, DOH has the power to delay the transaction until the review’s completion, however, closing cannot be delayed more than 180 days from the completion of the preliminary review. As part of a review, DOH may require the parties to the transaction (including parent and subsidiary companies of the parties) to submit additional documentation and information as necessary. Additionally, DOH may require that the parties to a transaction pay to DOH all actual, reasonable, and direct costs incurred by DOH in reviewing and evaluating the notice. Any information obtained by DOH pursuant to the cost and market impact review may be used by DOH in assessing certificate of need applications submitted by the parties. The proposed amendment to the Disclosure of Material Transactions Law in the FY 2026 Executive Budget does not propose a DOH approval process for material transactions, as initially sought in the FY 24 Executive Budget. However, it does give DOH the power to delay transaction closings until it receives all requested information from the parties.

Five-Year Transaction Reporting Requirement

The proposed amendment would add an annual reporting requirement for five years following the transaction’s closing. Each year on the anniversary of the transaction’s closing, the parties to the material transaction would need to provide a report to DOH so that DOH can assess the impact of the transaction on cost, quality, access, health equity, and competition. In addition, DOH may require any parents or subsidiaries of the parties to the material transaction to submit to DOH within 21 days upon request information needed for DOH to assess the impact of the transaction on cost, quality, access, health equity, and competition.

Implications

The proposed amendment indicates the DOH’s desire to heavily regulate and increase its oversight over health care transactions in New York. Including a cost and market impact review signals that DOH may be trying to move toward a more comprehensive review and approval process similar to the framework implemented in Massachusetts in 2012. For providers and other entities who are currently party to a transaction, or contemplating entering into such a transaction, that would be subject to the Disclosure of Material Transactions Law, it is important to note that these proposed amendments may significantly lengthen the timeline of your transaction. In this case, it may behoove such providers and others to proceed with such transactions sooner rather than later.

We will continue to monitor and report on this proposal and other state legislative efforts to broaden the scope of government review of health care transactions.

Global M&A Trends: Spotlight on Japan

According to a recent KPMG report, the global M&A landscape in 2024 signals a rebound despite challenges like geopolitical tensions, high interest rates, and persistent inflation for much of the year. The dealmaking environment gained momentum in part due to inflation and interest rate pressures starting to ease towards the end of the year, the return of major lenders to acquisition finance markets, and technology advancements, particularly artificial intelligence (AI).

Although 2024 marked a turnaround for global M&A markets, performance was mixed. The KPMG report states that while deal volumes declined by approximately 17%, the total deal value rose, driven by 89 megadeals totaling an impressive $1.034 trillion. However, smaller deals (valued under $500 million) experienced a dip in both value and volume.

Private equity (PE) firms faced hurdles in closing new funds, reflecting challenges in the broader dealmaking environment. However, last September, a pivotal moment arrived when the US Federal Reserve initiated a rate cut. This infused a cautious optimism into the market.

Stable interest rates, cooling inflation, and abundant dry powder sparked a renewed interest in PE markets. Valuation gaps started to narrow, and lenders, both traditional and private credit funds, started offering more favorable financing terms.

Spotlight on Japan

While the Americas attracted around half of the total deal value in 2024, the biggest gains were seen in Japan. Last year was a busy year for Japan-related mergers, thanks in part to private equity funds snapping up businesses being shed by companies that have become increasingly focused on capital efficiency.

According to a JP Morgan report, after three decades of deflation and stagnant growth, recent government and market reforms designed to improve corporate governance and capital management have encouraged corporates to embrace a more transparent, pro-growth agenda. This has led to a wave of dealmaking in Japan.

The volume of mergers and acquisitions linked to Japan was up around 20% in the first half of the year compared to 2023 and was followed by a strong performance in the second half of 2024. Japan-related deals accounted for over 20% of Asia’s entire transaction volumes for 2023, the highest in four years, MARR data showed. Much of this has been driven by increases in shareholder activism and PE activity.

Japan’s recent reforms and renewed focus on growth create opportunities for US companies to expand in a potentially undervalued but stable market, particularly when the yen is hovering at multi-decade lows.

Japan’s M&A activity towards the US is being influenced by economic conditions, currency, and the regulatory environment. While the weak yen makes overseas investments more expensive for Japanese acquirers, a strong US economy compared to Japan’s stagnant growth encourages Japanese companies to pursue acquisitions in the US as a growth strategy.

2025 Outlook: Optimism on the Horizon

Recent coverage in Bloomberg indicates that Japan’s dealmakers are expecting a busier 2025 after more than $230 billion in mergers and acquisitions last year. In 2024, the value of M&A deals that involved a Japanese company rose 44% to more than $230 billion, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. That’s the fastest growth since 2018 and compares with a 38% rise in M&A activity across the Asia-Pacific region.

Much of this increase was due to a jump in foreign PE firms looking for undervalued companies in Japan. According to Pitchbook, PE deals in Japan with foreign PE participation reached an all-time high in 2024, a pace that seems to be continuing. Bain Capital recently announced the acquisition of 300-year-old Tanabe Pharma for $3.4b, which was the largest PE deal ever announced in the Japanese healthcare sector.

While the forecast is positive, dealmaking activity remains susceptible to unexpected disruptions. That said, if current trends remain steady, 2025 could solidify itself as a year of robust growth in M&A markets.

Where Is Corporate Venture Capital Headed In 2025, And Will It Lead To More M&A?

Corporate Venture Capital (CVC) investment is an increasingly used strategic tool that enables large corporations to make minority investments in startups that will complement and expand their existing products or services. This type of investment can be highly beneficial as it can provide strong financial returns, as well as access to innovation, without the time and heavier expense load of in-house research and development (R&D) projects.

While many would think that an eventual merger, acquisition, or other type of M&A transaction would be the end goal of CVC investment, a recent analysis by PitchBook indicates that despite elevated CVC activity over the past 10 years, it has not resulted in much M&A. According to their data, from 2014 to 2024, CVC has made up more than 46% of total VC deal value and 21% of deal count. However, despite having invested a vast amount of capital, very little of this investment has translated to acquisitions.

To put it into perspective, their data shows that since 2000, below 4% of CVC-backed companies were acquired by an existing CVC investor. So, why aren’t more CVCs moving toward acquisitions, especially as their approach typically involves looking for companies who could provide great returns and complement or expand their existing products? The definition of what a strategic return looks like can vary greatly among CVCs. It could be access to new technologies or markets, driving innovation, competitive advantage, a boost to public image, or many other motivating factors. But for only a small fraction of CVCs, a strategic return yields an acquisition.

PitchBook points to several factors that might explain why M&A is not always their “end goal,” such as stage preference. CVC investors tend to focus on later-stage investment. This is due in large part to their interest in companies that have reached a more mature stage of product development and pose a lower risk. While some CVCs focus on earlier-stage investment, the asset class as a whole favors later-stage investment. It is simply more difficult and costly to integrate a company in its later stages into a larger corporation. And for those investing in earlier-stage startups, there are, of course, more risks that go along with acquisitions of these companies, as well as a higher risk of failure.

CVCs might also be motivated by a need for flexibility and options. As a minority stakeholder, they can have great insight into a startup’s innovation, inner workings, and competitive position with minimal risk. As conditions change, they still have the ability to pivot. That becomes much more difficult once they enter into an acquisition. There is also the issue of investing in complementary businesses versus those that you want to integrate into your corporation. Investing in a startup that is complementary to yours that allows access to new technologies or innovations does not necessarily mean it makes sense to then fully integrate it into your organization.

Additionally, the goals of the startup may not be aligned with CVC M&A. CVCs are targeting later stage startups in larger numbers. At this stage, founders often have their sights set on an IPO as opposed to an acquisition, and even if their goal is to be acquired, there is likely more than one interested party, making the competition fierce. An IPO or sale to another buyer could still allow a CVC to realize some significant returns without going through the acquisition process.

While the goal of a startup might not be an acquisition by its corporate investors, there are some significant benefits that come with corporate investment. A study conducted by Global Corporate Venturing showed that startups that had corporate investors saw their risk of bankruptcy cut in half, as well as an increase in exit multiples in the case of an acquisition or IPO. This is likely due in large part to the additional advantages that can accompany corporate investment as opposed to traditional VC investment. These could include access to invaluable knowledge, facilities, distribution channels, or strategic partnerships. Corporate investment can also help to boost the profile of a startup, enhancing its visibility, providing validation, as well as a greater sense of stability.

There are many reasons why the actual number of acquisitions by CVCs is so low. It truly depends on the motivating factors of the company and what makes the most sense based on their short and long-term goals, as well as those of the startup. However, it is clear that CVC investment can come with incredible benefits for startups, and it is showing no signs of slowing down anytime soon.

New HSR Rules Go Live: Your Playbook for Effective M&A

Starting today, February 10, 2025, all merger filings will be subject to new Hart-Scott-Rodino (HSR) rules. The new HSR rules will fundamentally alter the premerger notification process, and substantially increase the burden on filing parties, who will need to provide significantly more information and documents with their initial filings.

Companies can take steps today to make filings under the new rules less burdensome and increase the likelihood of achieving antitrust clearance, such as collecting and regularly updating the “off-the-shelf” information needed for all filings, and engaging in earlier discussions with the legal team to identify potential overlaps and supply relationships and develop key themes around transaction rationales and impacts on competition that will need to be included in the filing.

In Depth

MAJOR CHANGES

The two biggest changes in the new HSR rules are the requirements to (1) submit new business descriptions of transaction rationales, competitive overlaps, and supply relationships; and (2) submit more business documents with the filing, including ordinary course strategic documents presented to the CEO or board of directors.

New Business Descriptions

For all transactions, the merging parties must:

Describe each of the principal categories of their products and services.

Identify and explain each strategic rationale for the transaction discussed or contemplated (including rationales later abandoned).

For transactions with competitive overlaps, the merging parties must:

Identify and describe the current products or services that compete with, or could compete with, the other party – including known planned products or services in development.

Submit data on sales of such products in the most recent year, a description of all categories of customer types by product (e.g., retailer, distributor, commercial, residential), and the top 10 customers for the product, and each customer category identified.

For transactions in which the parties have supply relationships, the merging parties must:

Describe each product or service (1) supplied to the other party or another entity that competes with that party, or (2) purchased or otherwise obtained from the other party or another entity that competes with that party; in both cases, above a de minimis threshold.

Submit data on sales or purchases from the other party and/or another entity that competes with that party, and the top 10 customers or suppliers for each such product or service.

More Business Documents

For all transactions, merging parties must include:

Transaction-related documents.

Parties must provide materials equivalent to what were formerly referred to as “Item 4 documents” and include confidential information memoranda, and documents that discuss the transaction in terms of markets, market shares, competitors, competition, synergies/efficiencies, and opportunities for sales growth/expansion into markets.

There is a new requirement to collect such documents not only from officers and directors, but also from the “Supervisory Deal Team Lead,” defined as the individual with the primary responsibility for supervising the strategic assessment of the transaction.

Draft documents presented to any board member must be included, unless the board member received such drafts in a deal team role and not in a capacity as a board member (clarified in recent “two hats” guidance from the Federal Trade Commission).

For transactions with competitive overlaps, merging parties must also include:

Ordinary course Plans and Reports (from within one year of filing), even if not prepared in connection with the transaction.

All documents shared with the board that discuss markets, market shares, competitors, or competition for the overlap product or service.

All regularly prepared reports (annual, semi-annual, or quarterly) shared with the CEO that discuss markets, market shares, competitors, or competition for the overlap product or service.

OTHER KEY CHANGES

CATEGORY

NEW OR UPDATED REQUIREMENTS

Officers and Directors

New requirement to identify officer or director interlocks with other businesses that have a vertical or horizontal competitive relationship with the target business.

Minority Shareholders or Interest Holders

Requires identifying minority holders (more than 5%, but less than 50%) anywhere in the acquiring entity’s corporate chain.Limited partners need to be identified if they have the right to influence the Board, such as by having the right to appoint or nominate a member – previously only general partners of limited partnerships needed to be listed.

NAICS Codes

Require filing persons to identify which operating business contributes to each North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) code.

Prior Acquisitions

Both buyer and target need to report certain prior acquisitions involving products or services in the Overlap Description (not just NAICS overlap).

Defense/Intelligence Community Contracts

Must report contracts valued at $100 million or more involving horizontal overlaps or vertical supply relationships.

Foreign Subsidies

Must report financial subsidies from certain foreign countries or entities (e.g., China, Russia, Iran, North Korea).

IMPLICATIONS FOR MERGING PARTIES

Earlier Antitrust Counsel Involvement is Critical

Assessing Overlaps

The data and documents needed to file differs significantly for transactions with competitive overlaps, therefore determining whether there is an overlap early in the process can significant benefit this workstream – overlap deals may require bringing more employees “in the tent” to facilitate gathering of necessary documents, data, and information.

Exchanging NAICS codes with other party (via antitrust counsel) should be advanced earlier in the process. Sellers should consider pushing buyers for overlap input earlier in the process because filings with even limited overlaps (and no significant antitrust issues) under the new HSR rules will, nonetheless, require substantially more preparation to file.

Reviewing ordinary course strategic documents that will be filed is critical, because overlap descriptions in the filing need to be consistent with such documents.

Developing – and Documenting – Key Themes

More documents being submitted with the initial filing provides more opportunities for government agencies to identify and investigate potential issues.

It is important that these documents are accurate and based on real data/facts and avoid content that can be misconstrued in a way that could be harmful for competition reviews. Employees at portfolio companies who prepare such documents presented to the company CEO or the board should consult and share drafts with the legal team before sharing/finalizing.

Early discussions with the legal team to develop and document transaction rationales is important because parties must in their business descriptions, explain any inconsistencies with Business Documents.

Changes to Antitrust Provisions in Purchase Agreements

Timing

The time to prepare an HSR filing is substantially increased under the new HSR rules.

HSR timing provisions will need to be updated to provide greater time/flexibility (e.g., no longer a specific timeline, but a shift to “as soon as reasonably practicable”; longer timelines, such as 20 business days or 30 days).

Pre-signing HSR preparation is critical to be able to proceed quickly.

Cooperation

With more advocacy and documents submitted with the initial filing, more robust cooperation provisions should be incorporated into purchase agreements to cover sharing of the draft filings/submissions between counsel.

STEPS THAT CLIENTS CAN TAKE NOW TO MAKE HSR FILINGS MORE EFFICIENT AND SUCCESSFUL

Companies can consider the following steps to prepare for the new filing regime:

With counsel, draft high-level descriptions for each active portfolio company investment or operating company, describing each of the products and/or services provided by the company.

Maintain a list of NAICS codes for each active operating business.

Develop a list of minority shareholders holding more than 5% but less than 50% of each holding company, fund, portfolio company, and/or subsidiaries.

Create a list of prior acquisitions within the previous five years for each portfolio company, organized by product or service lines.

Collect and organize all board documents and regularly prepared documents shared with the CEO that discuss markets, market shares, competitors, or competition.

Refresh – and expand – document creation training for employees likely to draft Business Documents.

SECURE Act 2.0 Mandatory Automatic Enrollment Requirements for New Retirement Plans Guidance Released

One of the hallmarks of the SECURE 2.0 Act of 2022 (SECURE Act 2.0) legislation was to increase participation in retirement plans. On January 10, 2025, the Treasury Department and the IRS came one step closer when they announced the issuance of proposed regulations requiring automatic enrollment for new Code Section 401(k) and 403(b) retirement plans (Proposed Regulations). As background, the SECURE Act 2.0 added Code Section 414A, which provides that a retirement plan will not be qualified unless it satisfies certain automatic enrollment requirements under Code Section 414(w). These requirements:

Require automatic enrollment of employees with elective deferral contributions of at least 3% and no more than 10% in the first year of participation (with 1% increases between 10-15%)

Permit participants to withdraw their automatic elective deferrals within 90 days of their first elective deferral contributions being made

If no investment election is made, permit the automatic elective deferrals to be invested in qualified default investment alternatives (QDIAs)

The legislation, as originally enacted, provides that the automatic enrollment requirements do not apply to 1) retirement plans established before December 29, 2022; 2) retirement plans that have been in existence for less than three years; 3) governmental plans; 4) SIMPLE 401(k) plans; and 5) retirement plans with fewer than 10 employees. The Proposed Regulations provide additional regulatory guidance and clarification on issues such as eligibility for the automatic enrollment feature, contribution requirements, permissive withdrawals and investment requirements. The Proposed Regulations also incorporate previous IRS automatic enrollment guidance issued last year (provided in Notice 2024-2) with some modifications.

Highlights From the Proposed Regulations

Eligibility – Provides that an employer cannot exclude groups of employees, and the automatic enrollment requirements must apply to all employees eligible to elect to participate in the plan. However, an employer can exclude employees who already have an election on file (whether an election to contribute or to opt out) on the date the plan is required to comply with the automatic enrollment requirements.

Contribution limits – Clarifies how an employee’s “initial period” is determined for purposes of initial contributions. The initial period begins on the date the employee is first eligible to participate in the plan and ends on the last day of the following plan year. This is important for the application of the automatic escalation rule that requires the plan to automatically increase an auto-enrolled participant’s contribution percentage by one percentage point (up to 10%) each plan year following the employee’s initial period.

Plan mergers and spinoff – Generally, incorporates guidance provided in Notice 2024-2 regarding the application of the automatic enrollment requirement to plans that are the result of mergers but expands the guidance to address mergers involving multiple employer plans; incorporates the guidance in Notice 2024-2 regarding spinoffs. Importantly, the merger of two plans established prior to December 29, 2022, into one plan will not create a new plan subject to the automatic enrollment requirements.

New and small business – Provides that the automatic enrollment requirements should start on the first day of the first plan year that begins after the employer has been in existence for three years. Further, the 10-employee requirement is determined by the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA) regulations under Q&A-5, Treasury Regulation Section 54,4980B-2.

Multiple employer plans – Clarifies that if an employer adopts a multiple employer plan, the automatic enrollment requirements apply to the employer as if it adopted a single employer plan (i.e., they apply if adopted after December 29, 2022) regardless of when the multiple employer plan was adopted. This would not affect the employers who adopted the multiple employer plan on or before December 29, 2022.

The Proposed Regulations will not take effect until the first plan year beginning six months after the issuance of final regulations. However, the change in presidential administration (and related changes within the administrative agencies) casts uncertainty on whether these regulations will be finalized without further modifications or withdrawn all together. A plan sponsor should proceed in good faith to apply these rules until they are final.

Implementation of the Mobility Directive: Significant Changes for Mergers, Divisions and Conversions with the Introduction of a New Dual Regime

On 23 January 2025, Luxembourg enacted a bill implementing the EU Mobility Directive (2019/2121) for cross-border conversions, mergers and divisions, featuring (i) a harmonised legal framework for these transactions across the European Union, and (ii) a distinct set of rules for transactions not covered by the EU special regime.

Transposition of the EU Mobility Directive and Introduction of the EU Special Regime

The Luxembourg legislator has leveraged all available options under the EU Mobility Directive to create a favourable regime for company mobility within the transposition of the EU special regime. It applies to cross-border operations involving companies based in at least two EU member states, with the Luxembourg company being an SA (société anonyme), SCA (société en commandite par actions), or SARL (société à responsabilité limitée). This regime enhances consistency and clarity in the applicable EU cross-border operations while ensuring adequate protection, including:

Minority Shareholders Rights

Shareholders who voted against the European cross-border transaction may exercise exit rights and claim cash compensation. Those who did not exercise this right can challenge the share exchange ratio.

Information Rights

Rights to information include detailed explanatory reports from the management body for the benefit of employees and shareholders. Additionally, shareholders, creditors and employee representatives may submit comments on the draft terms.

Role of the Luxembourg Notary

The notary scrutinizes the transaction to ensure the legality of the planned cross-border operations.

General Regime Applicable to Domestic Transactions and Cross-Border Transactions Not Covered by the EU Special Regime

The general regime builds on the existing framework and simplifies procedures for conversions, mergers and divisions. Key points include:

Mergers Between Sister Companies

A simplified merger process has been introduced that does not require the issuance of new shares applicable when one party directly or indirectly owns all shares in both companies or when the same parties hold the same proportion of shares in each of the merging companies.

Domestic and Non-EU Cross-Border Mergers and Divisions

Draft Terms

The draft terms and board report need less-detailed information, and the merger or division might be contingent upon a condition precedent.

Independent Expert’s Report

Report is no longer mandatory for single-shareholder companies in case of mergers and divisions.

Non-EU Cross-Border Conversions

Unless there are employees and specific assets involved, only an extraordinary general meeting of the company’s shareholders before a Luxembourg notary is required to approve the conversion.

When Do the New Regimes Come Into Effect?

The new law will come into force on the first day following the month of its publication in the Luxembourg Official Journal. Once the new provisions come into effect, they will apply to all new restructurings. However, the new rules will not affect ongoing projects where the draft terms were published before the first day of the month following the law’s entry into force.

Competition and Consumer Law Round-Up

What’s Inside This Issue?

This edition of the K&L Gates Competition & Consumer Law Round-Up provides a summary of recent and significant updates from the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC), as well as other noteworthy developments in the competition and consumer law space.

Enforcement

NDIS Providers Warned Against Misleading Advertising

Misleading Pricing Alleged Against Woolworths NZ

Mergers and Acquisitions

Divestiture Required for Blackstone’s Acquisition of I’rom

Consultations

Treasury Consults on ACL Reform for AI-Enabled Goods and Services

Treasury Further Consults on ACL Prohibitions Against Unfair Trading Practices

Noteworthy Developments

Mandatory Merger Clearance Regime to Commence on 1 January 2026

ACCC Releases Sustainability Collaborations Guidelines for Businesses

ASIC’s Enforcement Priorities Focus on Cost-of-Living Pressure

Click here to view the Round-Up.

RWI in Health Care M&A: Part 2 [Podcast]

In part two of this two-part series, Matt Miller and Andrew Lloyd analyze representations and warranties insurance (RWI) in the health care M&A landscape.

They discuss the process of finding and securing an insurance underwriter, practical tips for structuring and negotiating RWI policies, how to navigate a claim after the policy is in place, and future trends in the RWI market.

Find part one of this series here.

5 Trends to Watch in 2025: AI and the Israeli Market

Israel’s AI sector emerging as a pillar of the country’s tech ecosystem. Currently, approximately 25% of Israel’s tech startups are dedicated to artificial intelligence, according to The Jerusalem Post, with these companies attracting 47% of the total investments in the tech sector (Startup Nation Finder). This strong presence highlights Israel’s focus on AI-driven innovation and entrepreneurs’ belief in the growth opportunities related to AI. The Israeli AI market is expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 28.33% from 2024 through 2030, reaching a value of $4.6 billion by 2030 (Statista). This growth is driven by increasing demand for AI applications across diverse industries such as health care, cybersecurity, and fintech. Government-backed initiatives, including the National AI Program, play a critical role in supporting startups by providing accessible and non-dilutive funding for research and development (R&D) purposes. Despite facing significant challenges since the start of the war in Gaza, Israel has continued to produce cutting-edge technologies that are getting the attention of global markets. Additionally, Israel’s highly skilled workforce and partnerships with academic institutions provide a steady supply of talent to meet the sector’s demands. With innovation, resilience, and collaboration at its core, the Israeli AI landscape is poised to remain a global force in 2025 and beyond.

Mergers and acquisitions to remain a cornerstone of deals. According to IVC Research Center, 47 Israeli AI companies successfully completed exits in 2024, showcasing the global demand for AI-driven innovation. Investors are continually identifying the differences between companies whose foundations were built on AI, versus those leveraging AI to enhance other core elements of their value proposition—sometimes only marginally. Savvy buyers look beyond the “AI label” and seek out companies with genuine, scalable AI solutions rather than superficial integrations, understanding that value lies in robust and transformative applications. AI is also sector agnostic and may disrupt virtually every vertical. From health care and finance to retail and manufacturing and others, numerous industries are increasingly leveraging AI to enhance or even change their core competency to gain competitive advantages. Deals in this space are coming from strategics such as automobile manufacturers, banks, digital marketing companies and life science firms, among others. As AI continues to permeate multiple sectors, Israeli companies are poised to receive increased attention from strategic M&A buyers looking to unlock new technologies and business opportunities in the market.

Intersection of PropTech and AI to further revolutionize the global real estate industry. Israeli innovation is expected to be at the forefront of this trend. According to IVC Research Center, over 70 PropTech companies headquartered in Israel are leveraging AI to develop cutting-edge technologies that are reshaping the industry on a global scale. We anticipate these companies will continue advancing AI-driven tools and third-party solutions to streamline acquisition strategies, enhance underwriting processes, and drive operational efficiencies. By harnessing AI to identify leasing opportunities, forecast rental trends, and optimize costs, Israeli PropTech firms are set to solidify their position as global leaders in real estate innovation in the year ahead.

AI to become increasingly important across global industries. Israeli companies have demonstrated genuine thought/R&D leadership in AI innovation. Some of the AI-centric legal trends that may stand out in 2025 include (1) a greater focus on data rights management as Agentic AI continues to carve new learning standards; (2) regulatory advancements in science, highlighted by two AI-related Nobel Prizes in science, that will likely materialize in the U.S. Food and Drug Administration adopting new rules for AI-driven drug approvals, as well as new AI patenting standards and requirements; (3) greater emphasis on responsible AI usage, particularly around ethics, privacy, and transparency; (4) the adoption of quantum AI across many industries, including in the area of securities trading, which will likely challenge securities regulators to address its implications; and(5) turning to AI-powered LegalTech strategies (both in Israel and in other countries). Israeli entrepreneurs are likely to continue working within each of these industries and help drive the AI transformation wave.

AI-based technology to continue changing how companies handle recruitment and hiring. While targeted advertising enables employers to find strong talent, and AI-assisted resume review facilitates an efficient focus on suitable candidates, the use of AI to identify “ideal” employees and filter out “irrelevant” applicants may actually discriminate (even if unintentionally) against certain groups protected under U.S. law (for example, women, older employees, and/or employees with certain racial profiles). In addition, AI-assisted interview analysis may inadvertently use racial or ethnic bias to eliminate certain candidates. Israeli companies doing business in the United States should not assume their AI-assisted recruitment and hiring tools used in Israel will be permitted to be utilized in the United States. Also, Israeli companies should be mindful of newly enacted legislation in certain U.S. states requiring companies to notify candidates of AI use in hiring, as well as conduct mandatory self-audits of AI-based employee recruitment and hiring systems. AI regulation on the state level in the United States is likely to increase, and Israeli companies that recruit and hire in the United States will be required to balance their use of available technology with applicable U.S. legal constraints.

2025 HSR Thresholds and Filing Fees Published, Effective in 30 Days

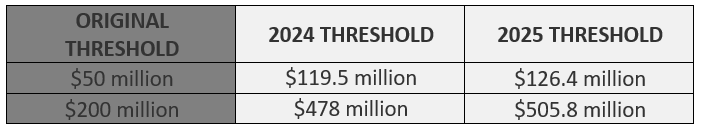

What Happened: The Federal Trade Commission published revised Hart-Scott-Rodino (“HSR”) thresholds and updated filing fees, and revised thresholds for interlocking directorates, in the Federal Register. The new thresholds and filing fees become effective on February 21, 2025.

The Bottom Line: The new HSR thresholds are higher than current thresholds, and the new filing fees have been increased for transactions valued above $555.5 million. The new interlocking directorates thresholds are also higher. Clients contemplating mergers or acquisitions or appointing board members need to be aware of the new thresholds and filing fees. Companies may need to file with the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) and Department of Justice (“DOJ”) if the value of the deal exceeds $126.4 million.

The Full Story:

HSR Thresholds and Filing Fees

The FTC revises the HSR thresholds each year based on gross national product, and now also revises filing fees and fee tiers based on gross national product and CPI. Generally, under the revised thresholds, if the “size of transaction”—value of non-corporate interests, assets, voting securities or a combination thereof held as a result of the transaction—exceeds $505.8 million and no exemption applies, the parties must file. If the size of transaction exceeds $126.4 million but is less than $505.8 million, then antitrust counsel will need to do a “size of person” analysis. Generally, an HSR filing will not be required unless one party to the transaction has total assets or annual net sales of $25.3 million or more and the other party has total assets or annual net sales of $252.9 million or more.

The new Size of Transaction thresholds are as follows:

The new Size of Person thresholds are as follows:

The notification thresholds for less than 50% acquisitions of voting securities, which are designed to act as exemptions, also increased as follows:

Pursuant to the Merger Filing Fee Modernization Act signed into law at the end of 2022, the HSR filing fees now have a six-tier structure, and the thresholds and the amount of the fee for each tier have been adjusted based on changes to gross national product and the consumer price index.

The civil penalty for violating the HSR Act is also expected to increase soon. The current penalty is $51,744 per day for each day of noncompliance.

Interlocking Directorates

The FTC also published revised thresholds relating to interlocking directorates based on gross national product. Section 8 of the Clayton Act prohibits a person from serving simultaneously as an officer or director of two or more competing corporations, subject to certain exceptions. Under the revised thresholds, Section 8 may apply when each of the competing corporations has capital, surplus and undivided profits aggregating more than $51,380,000 and each corporation’s competitive sales are at least $5,138,000.

Conclusion

HSR and interlocking directorates analysis is fact-specific and requires a comprehensive and thorough understanding of both the statute and relevant regulations. Clients are advised to consult with antitrust counsel as early as possible to determine if an HSR filing is needed before closing the deal or when appointing board members.

Big Law Redefined: Immigration Insights Episode 5 | Where Employment and Immigration Law Collide: Tips for In-House Counsel and HR Managers [Podcast]

In this episode of Greenberg Traurig’s Immigration Insights series, host Kate Kalmykov is joined by GT colleagues and Labor & Employment Shareholders Kristine Feher and Raquel Lord to discuss common employment law issues questions including wages, audits, mergers and acquisitions, performance management, and terminations.