An Updated Outlook for Private Equity in 2025

This year is off to a bumpy start in terms of dealmaking. A multitude of factors, including tariff-a-geddon, supply chain disruption, stubbornly high long-term interest rates (not coming down as expected), deregulation (not yet commenced, much less bearing any fruit), and an increasingly volatile stock market, have together summarized in the now ubiquitous term “market uncertainty” and have slowed the pace of dealmaking significantly. The impact of market uncertainty has been especially pronounced in the Private Equity (PE) space. In this context, PitchBook analysts have revised their outlook for the PE landscape for the balance of 2025.

Their new US PE Pulse report highlights the fast evolving picture for PE in 2025 in the face of what they term “meaningful macroeconomic threats.” In just December of 2024, their expectation was for stronger exit opportunities, along with some challenges related to capital deployment as the projection was for valuations to rise. They have now reversed that position, with an expectation of tougher exit conditions, coupled with more attractive capital deployment as sellers become more motivated.

One significant factor at play here is what they call “high-impact policies” from the new administration that stand to create “substantial economic effects.” These are leading to a wave of uncertainty for PE firms, and they must reconsider their strategies as conditions shift and regulatory uncertainty persists.

As of late 2024, their data shows that exits were surging (79% YoY in Q4). However, the introduction of tariffs and the onset of market volatility is no doubt impacting exit planning, particularly for those industries that will be most affected such as manufacturing, industrials, and consumer goods.

In the most recent Deal Flow Predictor from SS&C Intralinks, they also consider the delay in interest rate reductions as a contributing factor that could prolong the stall in M&A activity. Everyone is watching to see what the Fed will do in the face of rising economic pressures. But the report also points to the significant pressure on PE firms to execute deals and the expectation of eventual rate cuts that, when combined, could lead to “pockets of activity in strategic sectors.”

As this time of uncertainty does not seem to be ending any time soon, some exit windows might be closed or suboptimal for the foreseeable future. This is a time when PE firms can pivot to value creation mode, taking a strategic and proactive approach to protecting and growing value for their portfolio companies. This could mean looking at operational improvements or optimization of balance sheets, or even bolt-on acquisitions to buy smaller, synergistic companies at more attractive valuations that will boost value when exit conditions improve.

Even if a full exit is not feasible, there are also partial or structured exits to consider, including dividend recapitalizations, minority sales or spin-offs to continuation funds, or other vehicles. And there is always the option to reposition portfolio companies, whether that means reducing geographic or regulatory risks, or even pivoting toward a sector that is more insulated from volatility. No matter how firms choose to use this time, it is important to be strategic so they are ready when the exit window opens again, as it no doubt will.

We believe there is much reason to be optimistic for the balance of this year, despite the many challenges the private equity world is facing. Pitchbook’s report cites approximately 3,800 US PE-backed companies that have been held between five to 12 years and are waiting for their exit opportunities. And with close to $1 trillion of dry powder sitting on the shelf, PE firms are going to be looking to deploy that capital as conditions make putting that cash to work more and more attractive.

What Every Multinational Company Should Know About … Customs Enforcement and False Claims Act Risks (Part I)

As detailed in our prior article on “What Every Multinational Company Should Know About … The Rising Risk of Customs False Claims Act Actions in the Trump Administration,” the Department of Justice (DOJ) is encouraging the use of False Claims Act (FCA) claims to address the underpayment of tariffs by importers. In addition, many of President Trump’s new tariff proclamations have directed Customs to prioritize enforcing the new tariffs while also stating that Customs should assess the maximum penalties for underpayments without considering any mitigating factors. This article is the first in a series that highlights the heightened risks of importing in a high-tariff, high-penalty environment based on a comprehensive review of all prior FCA enforcement actions based on underpayment of tariffs.

As detailed in other articles in this “What Every Multinational Company Should Know” series, Customs has full access to electronic data from every importer for every entry through the Automated Commercial Environment (ACE) portal. This gives Customs the ability to run sophisticated algorithms, to find anomalies and ferret out potential underpayments. This includes comparing importers’ import patterns and entry-specific information (valuation, country of origin, etc.) not only against their own prior entries but also those of competitors bringing in similar merchandise. Much of this data also is available publicly, and the FCA permits private relators to file qui tam suits in the government’s name. The end result is that Customs and relators have the unparalleled ability to find underpaid tariffs.

There are five elements working to create a sharply increased risk profile for importers:

Heightened tariff levels, which make it possible to run up tariff underpayments and associated penalties very quickly.

Customs’ increased attention to tariff underpayments, particularly for the new Trump tariffs.

The threatened use of alternative enforcement tools on top of normal Customs penalty procedures, including the FCA and potential criminal penalties.

The increasing incentives for employees, competitors, and other potential relators to become whistleblowers.

The enhanced ability of Customs and plaintiff law firms to target and identify tariff underpayments.

The Customs enforcement and FCA risks are especially high for declaring the correct country of origin. This risk is encapsulated by the March 25, 2025 settlement of a Customs FCA action for $8.1 million. According to the DOJ, the importer misrepresented the country of origin of certain wood flooring imports by declaring them to be a product of Malaysia instead of the proper country of China, thereby paying the far-lower tariff rates levied on products of Malaysia.

Several aspects of this settlement are especially notable in the current high-tariff environment:

The underlying qui tamcomplaint did not contain specific evidence of scienter beyond the allegedly inaccurate statements on customs documents, although the government’s investigation likely uncovered such evidence because the FCA requires that false statements be made “knowingly.”

The settlement amount was based on unpaid duties from three different types of tariffs: antidumping duties, countervailing duties, and section 301 tariffs, all of which simultaneously applied to imports of wood flooring manufactured in China. While this type of multiple-tariff importation used to be rare, many of the new tariffs announced by the Trump administration “stack,” which means it will be common for entered products to be subject to multiple tariff regimes. This increases the chances of errors quickly multiplying and creating a much higher risk exposure.

In its press release, the DOJ highlighted the role that CBP played in the case, including how it made factory visits, detained shipments, analyzed import records, and conducted witness interviews. We expect this type of cooperation will become a regular feature of Customs FCA actions, as Customs has long-established expertise in identifying tariff underpayments.

The settlement states that the relator was a competitor of the importer, which ended up receiving $1,215,000 of the settlement proceeds. This is a reminder that FCA risks can arise from employees, former employees, suppliers, competitors, or even customers who could file qui tam suits as relators. Further, because services exist that gather import-related data and sell it to the general public, all of these parties — or relator-side law firms — could data mine this information to look for opportunities to file qui tam actions in hopes of achieving a similar payday. This also serves as a reminder that it is important for importers to file manifest confidentiality requests every two years, to minimize the amount of such information released to the public.

The allegations of underpaid duties were all related to the alleged failure to declare the correct country of origin. With the announcement of the new “reciprocal tariffs,” the country of origin generally will be the primary determinant of the amount of tariffs due. We accordingly expect Customs to focus heavily on whether importers are correctly declaring the country of origin, particularly when importers declare the country of origin to be low-tariff countries like the United Kingdom or Singapore.

Indeed, we expect that this specific fact pattern of misrepresenting the country of origin on goods will lead to numerous FCA actions. That fact pattern was present in one of the largest FCA cases, which resulted in the importer of printer ink paying $45 million in 2012 to resolve allegations that it misrepresented the country of origin on goods to evade antidumping and countervailing duties. In that settlement, the DOJ stated that although the printer ink “underwent a finishing process in Japan and Mexico before it was imported into the United States, the government alleged that this process was insufficient to constitute a substantial transformation to render these countries as the countries of origin.”

Preventing and Remediating Customs and FCA Enforcement Risk

The combination of increasing Customs FCA activity and sharply increasing tariff levels leads to the following corollaries that every importer should know:

Corollary #1: In a high-tariff environment, errors in Customs compliance can lead to quickly mounting underpayments of tariffs, thereby sharply increasing the risk profile of acting as the importer of record.

Corollary #2: In a high-tariff environment, Customs compliance is thus more important than ever.

Corollary #3: In a high-penalty environment, the aggressive and consistent use of post-summary corrections to fix import-related errors before they become final is also more important than ever.

Corollary #4: In an environment where Customs assesses penalties without considering mitigating factors, making voluntary self-disclosures is an essential tool to minimize Customs penalty risks, because Customs does not assess penalties for voluntarily disclosed conduct without analyzing aggravating and mitigating factors.

Corollary #5: In an environment of enhanced FCA actions, taking steps to minimize the risk of qui tamrelators is essential for all tariff-related issues.

These realities and recent enforcement cases underscore the importance of importers carefully reviewing areas where Customs is focusing its enforcement attention, which undoubtedly will include any shipments from low-tariff countries in light of the global and reciprocal tariff announcement. If the third-country processing or manufacturing is not enough to support an argument that the inputs were substantially transformed into a product with a different name, character, or use, thereby essentially changing its identity, then the importer could be accused of making a false statement by declaring an improper country of origin.

In sum, the combination of the new high-tariff environment, the heightened ability of Customs (and the general public) to data mine, and the stated emphasis of the DOJ to focus on and encourage the use of the FCA substantially increases import-related risks. In subsequent articles, we will highlight additional areas where we see heightened enforcement risk so that importers can take proactive steps to avoid Customs and FCA penalties.

US Customs and Border Protection Issues Guidance on Reciprocal Tariffs

US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) issued guidance on its Cargo Systems Messaging Service[1] on April 4, 2025 implementing the first round across-the-board 10% duty under the President’s reciprocal tariff executive order (the Reciprocal Tariffs EO), and issued additional guidance on April 8, 2025 concerning the Reciprocal Tariffs EO’s second round of country-specific tariffs (together, the CBP Guidance). The 10% duty went into effect on April 5 and the country-specific tariffs are effective on April 9, 2025. Both are imposed on most goods imported into the US, with narrow exceptions.

Tariff HTSUS Codes

A Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (HTSUS) code is a unique classification used to identify and categorize goods for import and export purposes. These codes help determine the applicable tariff rates and regulations for specific items entering the US.

10% Worldwide Tariff

The CBP Guidance requires importers to use HTSUS code 9903.01.25 when filing entry summaries for all imported goods subject to the 10% tariff. This applies to goods entered for consumption, or withdrawn from warehouse for consumption, on or after 12:01 a.m. EDT on April 5, 2025, unless they are subject to country-specific tariffs or fall under one of the exceptions listed below.

Country-Specific Tariffs

The CBP Guidance also requires importers to apply the following country-specific HTSUS code listed in Annex I of the Reciprocal Tariffs EO. These country-specific ad valorem duty rates will replace the 10% additional ad valorem duty under HTSUS code 9903.01.25. This applies to goods entered for consumption, or withdrawn from warehouse for consumption, on or after 12:01 a.m. EDT on April 9, 2025, unless they fall under one of the exceptions listed below.

HTSUS codes for select countries are set forth below; the full list is available in Annex I.

9903.01.50: Articles the product of Jordan or the European Union (Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden) will be assessed an additional ad valorem rate of duty of 20%.

9903.01.53: Articles the product of Brunei, Japan, or Malaysia will be assessed an additional ad valorem rate of duty of 24%.

9903.01.54: Articles the product of South Korea will be assessed an additional ad valorem rate of duty of 25%.

9903.01.55: Articles the product of India will be assessed an additional ad valorem rate of duty of 26%.

9903.01.63: Articles the product of China, including Hong Kong and Macau, will be assessed an additional ad valorem rate of duty of 34%.

9903.01.72: Articles the product of Vietnam will be assessed an additional ad valorem rate of duty of 46%.

Exceptions

The above tariffs do not apply to goods that fall within one of the following categories. Importers should not use the HTSUS codes listed above and should instead use the alternate HTSUS codes listed below:

9903.01.25 – Goods in transit with country-specific rates: Goods from countries with a country-specific duty rate are loaded onto a vessel in transit on or after 12:01 a.m. EDT April 5, 2025, and before 12:01 a.m. EDT April 9, 2025, and entered for consumption or withdrawn from warehouse for consumption before 12:01 a.m. EDT May 27, 2025, are subject to the 10% additional tariff, rather than the country-specific rate.

9903.01.26 – USMCA-origin goods from Canada: Goods that originate in Canada, including those entered free of duty under the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA).

9903.01.27 – USMCA-origin goods from Mexico: Goods that originate in Mexico, including those entered free of duty under the USMCA.

9903.01.28 – Goods in transit: Goods loaded onto a vessel at the port of loading before 12:01 a.m. EDT on April 5, 2025, and entered for consumption or withdrawn from warehouse on or after this date. Notably, CBP clarifies that importers have until 12:01 a.m. EDT on May 27, 2025 to declare these items to use this code.

9903.01.29 – Goods from sanctioned countries: Articles from countries subject to US sanctions (e.g., Belarus, Cuba, North Korea, Russia).

9903.01.30 – Donations for humanitarian purposes: Donations intended for human suffering relief, such as food, clothing, and medicine.

9903.01.31 – Informational materials: Goods considered informational materials, such as books, films, photos, microfilm, and news wire feeds.

9903.01.32 – Articles in Annex II: Goods specifically enumerated in Annex II.

9903.01.33 – Iron, steel, aluminum, and vehicle parts: Certain articles of iron, steel, aluminum, and passenger vehicles or light trucks, as well as parts subject to Section 232 actions.

9903.01.34 – Goods with US content: Articles with at least 20% US-origin content will not be subject to tariffs under the Reciprocal Tariffs EO on the US portion; only the non-US content will be tariffed.

The above tariffs also do not apply to goods that are properly entered under certain provisions of HTSUS Chapter 98, as long as they meet CBP’s regulations. However, there are important exceptions:

9802.00.80 – Articles assembled abroad: Additional duties will apply to the value of the assembled article from abroad, minus the cost of any US-made parts.

9802.00.40, 9802.00.50, and 9802.00.60 – Repairs, Alterations, or Processing: Additional duties apply to the value of the work done abroad.

Tariff Mitigation Strategies

De Minimis Exemption

As noted in our previous client alert, shortly after releasing the Reciprocal Tariffs EO, the Trump Administration issued another executive order announcing that the $800 de minimis exemption would not be available for goods originating in or shipped from China and Hong Kong. CBP’s guidance confirms that the exemption remains available for shipments from other countries—at least for now. Importers sourcing low-value goods from non-Chinese suppliers may continue to rely on Section 321 entry, though future limitations could be imposed.

Foreign Trade Zones (FTZs)

The guidance reiterates that goods entered into FTZs under privileged foreign (PF) status are subject to the reciprocal tariffs upon withdrawal. This means that even if importers process or assemble goods within the FTZ, they will still be subject to the reciprocal tariffs upon withdrawal for US consumption.

Duty Drawback

In our prior client alert, we noted that the Reciprocal Tariffs EO did not restrict duty drawback—suggesting the possibility of recovery. CBP has now confirmed that duties paid under the reciprocal tariff are eligible for drawback, an important clarification. Duty drawback provides flexible opportunities for relief, including:

Unused Merchandise Drawback – For goods exported without use in the US.

Manufacturing Drawback – For imported components used in goods that are exported out of the US.

Rejected Merchandise Drawback – For defective or nonconforming goods returned or destroyed under CBP supervision.

Third-Party Drawback Agreements – Importers without sufficient exports may partner with exporters to share drawback benefits.

Critically, across many drawback categories, the exported items need not be identical to the imported goods—as long as they share the same 8-digit HTSUS classification, they may qualify for drawback. This classification-based matching significantly expands eligibility and should be evaluated as part of any mitigation strategy.

Conclusion

The CBP Guidance offers critical clarity on tariff scope and administration while reinforcing the importance of compliance strategies. Importers should take proactive steps to prepare for the new tariffs by reviewing their operations and identifying potential mitigation strategies. This includes auditing HTSUS classifications to ensure accuracy, including the appropriate Chapter 99 codes for exemptions. Importers should also evaluate their supply chains to determine opportunities for sourcing alternatives or utilizing FTZs. Exploring duty drawback options is key, and importers should consider formalizing these programs where appropriate. It is essential to stay informed on any additional guidance, particularly regarding the country-specific tariffs effective on April 9. Early engagement with legal or trade advisors will help minimize exposure and facilitate compliance.

We continue to monitor developments and are available to assist clients in navigating this evolving landscape. For additional information, please contact the International Trade Controls team.

[1] We note that while CBP implemented the February and March tariffs imposed on Canada, Mexico, and China through Federal Register notices, it used the Cargo Systems Messaging Service (CSMS) for its most recent announcement on the reciprocal tariffs (and may follow up with Federal Register notices). The reason for this deviation from the norm is unclear (and may be simply a result of the fast-moving pace of changes to tariff policy), but industry should be aware of the distinction and should monitor CSMS as well as the Federal Register for changes.

Massachusetts Targets Founder’s Share Sale After Move…To New Hampshire

he Massachusetts Court of Appeals has ruled that, in some situations, a former resident of the Commonwealth can be liable for Massachusetts income tax on the sale of shares in a Massachusetts-headquartered company even after becoming a resident of another state. This case highlights a potential risk for business owners who assume that their liability for Massachusetts income taxes will end after they leave the Commonwealth.

The Case

Welch v. Commissioner of Revenue1 was an appeal from a decision by the Massachusetts Appellate Tax Board. Craig Welch founded AcadiaSoft, Inc. in 2003 when he was a Massachusetts resident. He worked for the company extensively and was a Massachusetts resident from the time he founded the business until he left the state for New Hampshire in 2015. From 2003 to 2014, he filed Massachusetts resident income tax returns. He took little salary for some of these years, but expected that his hard work would cause his shares in the company to appreciate. For all years in question, AcadiaSoft was headquartered in Massachusetts and paid Massachusetts corporate income tax.

Within two months of moving to New Hampshire, Mr. Welch entered into an agreement to sell his shares in AcadiaSoft and resigned as an officer and director of the company, contingent upon that sale. Despite Mr. Welch’s move north of the border before the sale, the Appeals Court upheld a prior ruling that Mr. Welch was nonetheless liable for Massachusetts state income tax on the capital gain. State tax law provides nonresidents of Massachusetts remain liable for tax on their “Massachusetts source income.” This includes “income derived from or effectively connected with… any trade or business, including any employment carried on by the taxpayer in the commonwealth, whether or not the nonresident is actively engaged in a trade or business or employment in the commonwealth in the year in which the income is received.”2 A Massachusetts tax regulation adds that income that is effectively connected with a trade or business generally does not include the sale of shares of stock in a C or S corporation if the gain is treated as capital gain for federal purposes. However, this gain can generate Massachusetts source income if it is related to the taxpayer’s compensation for services in Massachusetts.3

The Decision

The Appellate Tax Board concluded – and the Massachusetts Appeals Court agreed – that Mr. Welch’s gain from the sale of the shares was compensatory and effectively connected with his employment at AcadiaSoft. The court reasoned that Mr. Welch obtained the stock soon after founding the company, expected that it would be worth more in the future than when he started the company, and looked forward to a payout for his hard work. All of this made the gain from the sale of the shares Massachusetts source income – for a taxpayer who had already left the state.

Looking Ahead

The court’s opinion mentions the unique circumstances of the case, but it is easy to see how the reasoning could be applied more broadly. It is not unusual for an entrepreneur to expect that appreciation in a company in the future will be the reward for commitment to the business in the present. If such an entrepreneur devotes time and energy to a venture in Massachusetts, Welch suggests that the Commonwealth could tax resulting appreciation when a liquidity event eventually occurs, wherever that entrepreneur may then live.

If you have any questions about the information in this advisory, please contact your usual Goulston & Storrs attorney.

1 Welch v. Commissioner of Revenue, No. 24-P-109 (Mass. App. Ct. April 3, 2025).

2 G.L. c. 62, § 5A(a).

3 830 CMR ֻ§ 62.5A.1(3)(c)(8).

Understanding the Allocation of Tariff Payments

In the context of the tariffs imposed by the Trump Administration on imported goods, a prevalent misconception has arisen that foreign suppliers automatically bear the cost of these tariffs. The reality, however, is more complex. The actual payment of tariffs is significantly influenced by the specific contractual agreements between U.S. buyers and their foreign suppliers.

The Fundamentals of Tariff Payment

Contrary to popular belief, tariffs are not inherently paid by foreign suppliers. Legally, tariffs are paid by the importer of record at the time the goods enter the United States. Typically, the importer of record is the U.S. buyer or its agent. The ultimate economic burden of these tariffs is determined by the contractual arrangements among the foreign exporter, the U.S. importer, and any downstream customers of the importer. The economic impact of tariffs can thus be considered a shared burden, which is distributed according to contractual terms (and influence by market dynamics such as bargaining leverage), rather than automatically falling on foreign suppliers as sometimes portrayed in political discourse.

Contractual Provisions

International supply contracts frequently include provisions that state which party is responsible for duties and tariffs. If the contract specifies that the importer, usually the U.S. buyer, is responsible, then the importer will bear the cost of the tariffs.

Conversely, if the foreign supplier is designated as responsible for the tariffs, the foreign supplier will pay these costs.

Sometimes the contract sets forth these responsibilities through the use of the ICC’s International Commercial Terms (also known as Incoterms), which provide a shorthand spelling out the responsibilities for various costs in international trade transactions. For instance, the term Delivered Duty Paid (DDP) indicates that the seller is responsible for all costs, including duties and tariffs, until the goods reach the agreed location inside the buyer’s customs territory.

Conversely, terms like EXW (Ex Works) or FOB (Free on Board) place the burden of import duties and tariffs on the buyer.

Some sophisticated contracts have provisions that anticipate potential changes in duties, and include provisions that allow suppliers to adjust prices in response to new tariffs. Such contracts may permit adjustments in prices or allocation of payment burden in the event of changes in laws and regulations, including those on taxes and duties, and their interpretation after the effective date of the contract.

Ambiguous Contracts

Often supply agreements contain only a general provision, such as “The buyer shall pay the duties on the goods purchased from the seller.” Imagine a situation where a new 54% tariff is imposed on goods imported from China subject to such a clause. The Chinese seller will undoubtedly take the position that the buyer must pay. But the combination of a new tariff and a vague contract provisions may lead to a dispute. Additionally, there could be arguments about whether “duties” and “tariffs” are legally distinct, introducing further complexities in international trade law.

Seller might argue that buyer is responsible for all duties, including new tariff. Buyer could counter that its obligation is limited to duties that existed when the contract was signed, arguing that it would not have agreed to the contract if unforeseeable and substantial tariffs were to be buyer’s responsibility.

In such cases, buyer would be tempted to invoke a force majeure clause, if one exists, in light of the unforeseen tariffs. Courts typically do not consider a new tariff to be a standard force majeure event, unless the force majeure clause specifically lists tariffs as a covered event.

Market Dynamics

When the contract does not explicitly address tariff responsibility, the economic burden becomes a matter of negotiation between foreign exporter and U.S. importer. Foreign suppliers will not naturally pay the tariff unless they are obligated or incentivized to do so. Even if the delivery term is DDP (meaning the exporter pays U.S. duties), in high-tariff environment, the exporter may try to raise its price to offset its loss.

If the U.S. buyer is responsible for the tariff (for example, under any Incoterm other than DDP, or in the absence of a contract term), the U.S. buyer will be obligated to pay the tariff to U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Buyer then has three basic options: (a) pay the tariff and absorb the loss; (b) seek to renegotiate pricing with the foreign supplier to shift or at least share the loss; or (c) pass the tariff onto its customer.

The actual outcome will be heavily influenced by the market power or negotiating leverage of the exporter, importer, and customer. Foreign suppliers with unique products or strong market positions may be able to pass tariff costs to U.S. buyers. Conversely, U.S. buyers with significant purchasing power might pressure foreign suppliers to absorb the costs. In competitive markets, suppliers may have no choice but to absorb some or all of the tariff costs to maintain their U.S. customer base.

Conclusion

It is a misconception that tariffs are directly paid by foreign suppliers (unless President Trump intends to seek monetary payments from trade partners to reduce their trade surpluses with the United States). In reality, U.S. importers pay the tariffs to U.S. Customs, and whether the cost is absorbed by the buyer or passed back to the supplier depends entirely on the terms of the contract.

For businesses engaged in international trade, understanding the allocation of tariff payments has practical implications. It is advisable to review existing contracts to understand tariff liability provisions, take steps to clarify duty responsibilities with counterparties, and discuss steps for transactions going forward. Additionally, businesses should consider building flexibility into pricing structures to account for potential trade policy changes and diversifying supply chains to reduce dependency on heavily tariffed countries. Understanding who pays tariffs is not merely a legal or accounting issue; it is a strategic business consideration. In a global marketplace subject to changing trade dynamics, clear contract terms can make the difference between a manageable cost and a profit-killing surprise.

A Trap for the Unwary – Nonprofit Organization Compensation Arrangement Considerations for High Caliber Executives

Like any for-profit company, nonprofit organizations want to attract and retain high caliber executives to achieve and further their missions. To accomplish this, a nonprofit organization may have to offer a particularly robust compensation arrangement to the executive, especially because other nonprofit or for-profit organizations likely want to engage the services of such executive given the executive’s talent and proven high‑quality performance.

When negotiating a compensation arrangement, nonprofit organizations that are tax‑exempt under Section 501(c)(3), (4), or (29) should be aware of the potential for triggering an excess benefit transaction that may be subject to excise taxes under Section 4958 of the Internal Revenue Code, known as “intermediate sanctions.” In this blogpost, we briefly summarize the intermediate sanction excise taxes and some considerations for nonprofit organizations when designing and negotiating an executive’s compensation arrangement.

Intermediate Sanction Excise Taxes

Section 4958 of the Internal Revenue Code imposes on a disqualified person of a nonprofit organization that is tax-exempt under Section 501(c)(3), (4), or (29) a first tier 25% excise tax on the amount of an excess benefit transaction. If the excess benefit transaction is not timely corrected, Section 4958 imposes on the disqualified person a second tier 200% excise tax on the amount of the excess benefit transaction.

If the IRS determines that a nonprofit organization provides unreasonably high compensation to an executive that results in an excess benefit transaction, the executive is responsible for the Section 4958 excise tax. In addition, the directors, trustees, or executives of the nonprofit organization who approved the transaction may also each be liable for a 10% excise tax on the excess benefit transaction (capped at $20,000 each).

Additionally, depending on the facts and circumstances of an excess benefit transaction, the IRS may propose revocation of tax-exempt status, whether or not Section 4958 excise taxes are imposed.

Creating a Rebuttable Presumption of Reasonableness

Pursuant to regulations under Section 4958, a nonprofit organization may help protect against a finding by the IRS of an excess benefit transaction by creating a rebuttable presumption that a compensation arrangement was reasonable. Payments under a compensation arrangement are presumed to be reasonable if a nonprofit organization satisfies the following three requirements:

The compensation arrangement is approved in advance by an authorized body of the nonprofit organization (for example, the Board of Directors or the Compensation Committee) composed entirely of individuals who do not have a conflict of interest with respect to the compensation arrangement.

The authorized body obtained and relied upon appropriate data as to comparability prior to making its determination. Relevant information may include:

Compensation levels paid by similarly situated nonprofit and for‑profit organizations for functionally comparable positions;

The availability of similar services in the geographic area of the nonprofit organization;

Current compensation surveys compiled by independent firms; and

Actual written offers from similar institutions competing for the services of the executive.

The authorized body adequately documented the basis for its determination concurrently with making that determination.

If the nonprofit organization satisfies these three requirements, then the IRS may rebut the presumption only if it develops sufficient contrary evidence to rebut the comparability data relied upon by the authorized body.

Proskauer Perspectives

As a general matter, it is a best practice for a nonprofit organization to engage a compensation consultant to engage in a compensation benchmarking analysis based on a custom peer group. This serves two important purposes. First, a nonprofit organization can determine an appropriate compensation arrangement to offer an executive. And second, a nonprofit organization can utilize the analysis to satisfy the second requirement of creating a rebuttable presumption of reasonableness.

To attract and retain a high caliber executive, a nonprofit organization may have to offer a compensation arrangement that is significantly above the 50th percentile of the identified peer group. Depending on the facts and circumstances, it may be reasonable and justifiable to offer a very robust compensation arrangement, even between the 90th and 100th percentiles.

In such an instance, issues may arise if an executive attempts to negotiate for an incrementally more generous compensation arrangement, which is not uncommon to expect as part of a negotiation. Such increases in compensation may not just come in the form of obvious economic items like increases in base salary or bonus amounts, but could also come up in respect of certain perquisites, including enhanced retirement contributions, significant expense reimbursement obligations, security services for the executive (unless as a nontaxable working condition fringe benefit), company paid executive medical exams, and others. Increasing the amount of compensation and certain perquisites offered which deviates from the suggested maximum ranges in a compensation benchmarking analysis may give the IRS the contrary evidence it would need to rebut a presumption of reasonableness, and the IRS may impose excise taxes or even potentially a loss of tax‑exempt status.

Considering the potential for excise taxes and loss of tax-exempt status, it is important for both nonprofit organizations and executives to be mindful of possibly engaging in excess benefit compensation arrangements and to engage competent legal counsel.

Law Intern Nicole Arslanian assisted with writing this blogpost.

President Trump’s Tariffs Announcement and their Impact on Mexico

On April 2, 2025, U.S. President Donald Trump announced his tariff policy for numerous countries. In the case of Mexico, exported products that comply with the USMCA regulations are exempt from tariffs, which are approximately half of Mexico’s exports to the United States.

Products exported from Mexico that do not qualify as originating under USMCA provisions will be subject to a 25% tariff. Previously, these products were subject to a 2.5% tariff rate. The 25% tariff on products not protected under the terms of the USMCA, which account for half of Mexico’s exports to the U.S., and have an estimated value of US$300 billion, was enacted by Trump to press Mexico on preventing fentanyl trafficking and undocumented migration. If Mexico continues working with the U.S. on issues of fentanyl and unauthorized immigration, products not protected by the USMCA will be lowered to a 12% tariff rate. Manufacturers and other producers may address compliance with USMCA regulations, but this will not be simple and in the process, could become less competitive and lose market share.

Mexico had a slightly better outcome as it relates to tariffs in comparison with other countries. President Trump’s announcement could potentially usher in new investment opportunities for Mexico, particularly by international companies involved in the export of manufactured products to the U.S. severely affected by tariffs. Countries such as Taiwan (32% tariff), Vietnam (46% tariff), and South Korea (25% tariff), among others, which export approximately US$380 billion in products to the U.S. could potentially look to relocate manufacturing operations to Mexico to bypass tariffs for exporting to the U.S. under the USMCA rules.

The current trade landscape is highly complex. Multinational companies will need to find ways to remain competitive and keep market share while assessing what their global operations may look like in the future.

A Closer Look at Proposed Changes to Medicare Advantage in the “No UPCODE Act”

On March 25, 2025, U.S. Senators Bill Cassidy, M.S. (R-LA) and Jeff Merkley (D-OR) introduced the No Unreasonable Payments, Coding, or Diagnoses for the Elderly (No UPCODE) Act (the “Bill”).

According to Senator Cassidy’s press release, the Bill aims to improve how Medicare Advantage plans evaluate patients’ health risks, reduce overpayments for care, and save taxpayers money by removing incentives to overcharge Medicare. If passed, this Bill would have a tremendous impact on plans, vendors, and risk-bearing provider groups relative to Medicare Advantage (“MA”).

Background

Traditional Medicare (Parts A and B) reimburses health care providers based on the cost of services already rendered (known as “Fee-for-Service” or “FFS”). Conversely, MA functions as a prospective payment model, whereby Medicare Advantage Organizations (“MAOs”) contract with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (“CMS”) to administer and insure their respective member population.

MAOs are paid what amounts to be a fixed amount per member per month that reflects the projected health care costs of a given MAO’s members. MA payments are adjusted by CMS using a risk adjustment (“RA”) model, which weighs the relative health care financial risks of each member based on (1) his or her health status and (2) demographic information. Broadly and logically speaking, sicker members and/or those with more conditions are at risk for higher medical spend. Accordingly, MAOs are paid more under the RA model to address those risks.

This model is not without its criticism on both sides of the table. Health plans generally feel like changes to the payment model have a significant impact typically in the negative direction. For example, the most recent update to the V28 model has gutted funding for a number of cost-driving conditions. And budget hawks take the opposite view, i.e., that MA is, to some extent, overfunded and subject to overcoding and abuse. Nonetheless, the aim of the risk adjustment model (and MA/value-based care generally) is to ensure that MAOs and other MA entities are not deterred from caring for sicker patients.[1]

Senator Cassidy’s Bill purports to address concerns regarding perceived incentives that could lead to exaggerated health conditions aimed at securing improper payments.

Breakdown of the No UPCODE Act

If passed, the Bill would amend title XVII of the Social Security Act, starting in 2026, and implement the following changes to the MA program:

The Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (“HHS”), and under its umbrella, CMS, would use two years of patient diagnostic data in its RA model, instead of the existing one-year model;

Patient diagnoses identified through “chart reviews” and “health risk assessments” (“HRAs”) would be excluded entirely from the RA model; and

The Secretary of HHS would be required to assess the impact of coding differences between MAOs and traditional Medicare providers on risk scores, and to publicly report the findings, ensuring adjustments account for unrecognized coding pattern differences.

Implications on the Medicare Advantage Industry:

This is not the first time this Bill has been introduced in Congress, as Senators Cassidy and Merkley proposed an essentially identical bill in late March 2023 that did not lead to further congressional action.

The three components of this Bill would have a sizeable impact on the MA industry, as described in greater detail below.

Using Two Years of Diagnostic Data

The Bill requires CMS to use two years, rather than one year, of risk-adjusted data when determining payment. This facet of the Bill represents potential good news for MAOs, which spend time and money each year ensuring that chronic conditions are coded and submitted by a provider annually. The MA risk adjustment model, from a financial standpoint, currently “cures” all risk-adjusted diseases at the stroke of midnight each December 31, requiring annual recapture of diseases—even those that are chronic and/or do not resolve.

As discussed below, however, this may be inseparable from the other facets of the Bill, which render the upside of two years versus one year of data dubious. At a high level, requiring this change would appear to positively financially affect MAOs and MA value-based entities (“VBEs”), as their members/patients would now only need to have a Hierarchical Condition Category (“HCC”) attributed to them in just one of the prior two years to predict costs and trigger payment under the new RA model.[2]

The unintended consequence might be a reduction in patient care. The annual requirement of reconfirming diagnoses in many ways forces intervention by plans and their contractors. These take the form of in-home assessments, various gap closure interventions, and similar activities to effectuate a qualifying encounter with a licensed provider. As such, this change might have the unintended consequence of less care provided to MA beneficiaries, as MAOs and value-based entities may be disincentivized from identifying diagnoses and documenting them in the medical record on a yearly basis, as currently required, which in part incentivizes at least these annual provider encounters. This is especially true if in-home assessments are effectively hobbled by this Bill.

Notably, in its June 2020 Report to Congress, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (“MedPAC”) concluded from its study that using two years of diagnosis data to determine beneficiaries’ conditions produces payment adjustments that are about as accurate as using one year of diagnosis data, though it produces larger underpayments for those with high levels of Medicare spending than using one year of diagnosis data, which MedPAC attributes to lower coefficients for HCCs in the two-year RA model and high prediction-year (base year) spending.[3]

This means that not only did MedPAC determine that the two-year RA model would not substantively improve the predictive accuracy of the existing one-year RA model, but it would also likely result in greater underpayments to MAOs (and indirectly, VBEs) serving higher-risk member populations. MAOs and VBEs would naturally be reluctant to continue to serve those high-risk populations if they are not adequately compensated. This could lead to a reduction in members and potential increased utilization and government spending under traditional Medicare.

The 21st Century Cures Act in 2016 permitted CMS to use at least two years of diagnostic data, but CMS has yet to do so in nearly ten years. Doing so now would have a profound (and perhaps even unascertainable at this time) impact on the MA industry.

Excluding Diagnoses Identified from Chart Reviews and HRAs

Chart reviews, or so called “retrospective chart reviews” of medical records are utilized to help ensure member medical diagnoses—which are documented in the medical record, but for a variety of reasons are not submitted to health plans—are appropriately reflected in CMS data. Dropped or missing codes on claims data is exceptionally common. So common, in fact, that it birthed a private equity backed risk adjustment vendor industry. Providers typically focus on service level coding such as EM codes and CPT coding, not ICD diagnostic coding, and retrospective reviews are the last chance that plans have to ensure accurate data is submitted to CMS.

The prospective RA model, built to be an actuarial equivalent of FFS Medicare, requires MAOs to document all conditions to receive accurate payment. It stands to reason that MAOs (and VBEs) should utilize tools like retrospective chart review to capture valid conditions diagnosed and appropriately documented by a provider and submit member data that comprehensively reflects the risks the MAOs are assuming on behalf of CMS.

Should this Bill become law, plans and risk-bearing organizations that rely on retrospective review could be materially and negatively impacted. It would also likely serve as a death blow to a number of retrospective solutions vendors that provide such services.

HRAs differ significantly from chart review. HRAs are an established and longstanding practice in the MA care coordination model that are used to identify gaps in care, identify chronic conditions early, and prevent those conditions from worsening, causing comorbidities, or becoming more costly. These may occur in a patient’s home (often a vital component of comprehensive “In-Home Assessments” or “IHAs,” which are sometimes conflated with HRAs) or in the provider’s office. HRAs have evolved over the course of the MA program, as CMS has issued standards and best practices for conducting HRAs, and it continues to more broadly utilize other tools to ensure payment and data accuracy in MA (and in diagnosis codes identified via HRAs specifically), including through Risk Adjustment Data Validation (“RADV”) audits and HCC coefficient and model changes.

However, HRAs and IHAs have become the lightning rod for risk adjustment criticism by politicians, government agencies, and the media. Tapping into zeitgeist and perceived momentum, the Bill seeks to disqualify their use in the MA RA model. CMS has already taken a contrary view. CMS has, and continues to take, a balanced approach to these interventions and evaluated the appropriateness of using HRAs in MA. It has consistently supported their use, including in August 20, 2021 and September 5, 2024 letters from former CMS Administrator Chiquita Brooks-LaSure to the HHS Office of Inspector General (“OIG”) responding to OIG’s report that certain MAOs used HRAs to drive a disproportionate share of risk adjustment payments. Notably, in the 2024 CMS letter, CMS stated that it did not concur with OIG’s recommendation to “restrict the use of diagnoses reported only on in-home HRAs or chart reviews linked to in-home HRAs for risk-adjusted payments,” as it “allows MA organizations to use HRAs as a source of diagnoses used for the calculation of risk adjusted payments, as long as those diagnoses meet CMS’s criteria for risk adjustment eligibility.” To reinforce this point, CMS later addresses that it “will continue its efforts to conduct RADV audits to inform our understanding of the accuracy of these diagnoses.” CMS has also pointed out that despite OIG’s concern that diagnoses obtained from in-home HRAs may be inaccurate, OIG has “not conducted medical record reviews of the diagnoses that came from visits that may have contained an HRA and have not concluded that these diagnoses are not accurate.”

In addition to this support for HRAs in MA, CMS requires that Dual Eligible Special Needs Plans (“D-SNP”) use HRAs. If the Bill passes, it would likely cause confusion and potential misallocation of resources for MAOs with multiple plan products that have inconsistent legal requirements for HRAs. Additionally, similar to the above risks with excluding chart review-derived diagnosis codes from the RA model, if this Bill passes, MAOs and VBEs may forgo using HRAs altogether and instead initiate more basic encounters (like a less comprehensive PCP visit), which may lead to a deficiency in identifying and submitting diagnoses to CMS for payment under the RA model and therefore insufficient funds to manage the risk of the MAO’s member population.

Notably, this Bill charges the Secretary of HHS to “establish procedures to provide for the identification and verifications of diagnoses collected from chart reviews and health risk assessments,” but it does not give any other details, so it is unclear how these processes will be defined moving forward.

Adjustments in Coding Between FFS Medicare and Medicare Advantage

If passed, the Bill also requires CMS to calculate and publish the difference in coding growth between FFS Medicare and MA and set the adjustment to “fully account[] for the impact of coding pattern differences.” Currently, CMS applies a “minimum adjustment” of 5.9% for CY2025 pursuant to Section 1853(a)(1)(C)(ii)(III) of the Social Security Act, but this calculated adjustment would replace the minimum adjustment.

Importantly, CMS “may include [this coding intensity] adjustment on a plan or contract level,” meaning CMS could implement the adjustment differently among plans and contract years. This would create even more uncertainty for MA stakeholders.

Ultimately, given the wide-ranging implications this Bill will likely have on the MA industry and its members, MAO, VBEs, and other MA stakeholders should be monitoring this legislation and similar aims to materially change the MA program.

ENDNOTES

[1] It should also be noted that MAOs are bound to a percentage cap on profits, as Medical Loss Ratio (“MLR”) rules require MAOs to pay 85% of their revenue towards claims experience or quality improvement activities, with the remaining 15% allocated to various large administrative costs before profits are factored.

[2] For example, if projecting 2025 costs, DOS years 2023 and 2024 would be analyzed under the new RA model, and the MA beneficiary would need to have an HCC in just one of those years for the MAO to receive payment for that HCC.

[3] See Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (“MedPAC”) June 2020 Report to Congress. A separate, 2019 NIH study similarly found that incorporating additional years of clinical information into a Veterans Affairs prospective risk adjustment model did not result in a material increase in fit or predictive capability.

Liberation Day: President Trump Unveils Global, Reciprocal Tariffs – What You Need to Know

President Trump announced new tariffs on April 2, 2025, which he referred to as “reciprocal tariffs,” on almost all imports into the United States. The tariff package will be rolled out in two phases. Tariffs of 10 percent were imposed on all countries as of April 5. On April 9, additional, higher tariffs will be imposed on 57 countries, including the European Union, with which the United States has determined it has the largest trade deficits.

What Are the “Reciprocal Tariffs?”

According to a paper issued by the U.S. Trade Representative, the reciprocal tariffs “are calculated as the tariff rate necessary to balance bilateral trade deficits between the United States and our trading partners.” President Trump decided to impose only half of the rates calculated under that formula, while applying a minimum rate of 10 percent. Country-specific tariff rates span a range from the highest at 50 percent for Lesotho to the lowest at 11 percent for Cameroon and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The tariffs apply only to the non-U.S. content of an import, provided at least 20 percent of the import’s value is U.S. originating. Importers claiming partial exemption for U.S. content may be subject to rigorous auditing requirements.

President Trump enacted the new tariff package under the authority of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (“IEEPA”). The national emergency that the reciprocal tariffs are intended to address is the threat posed by the trade deficit and “other harmful policies like currency manipulation” that undermine the “national security and economy of the United States.” The President has previously used the IEEPA to impose tariffs on China, Canada, and Mexico to address illegal migration and imports of fentanyl into the United States

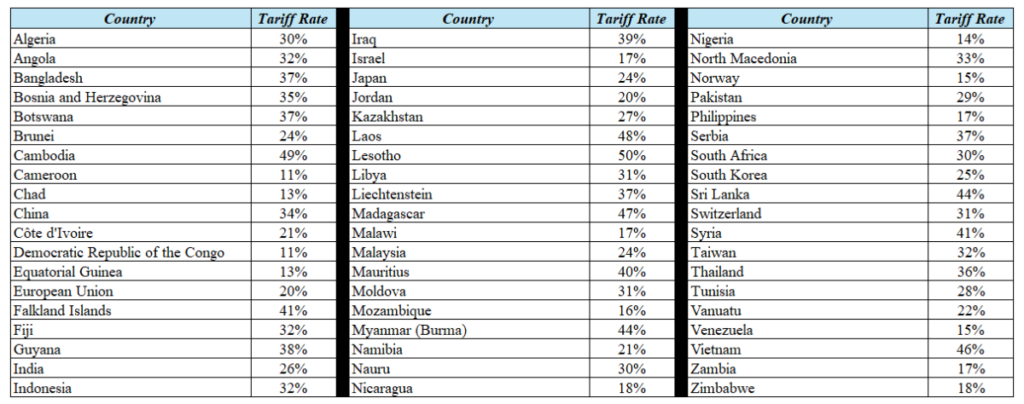

The current list of country specific tariff rates, as set out in Annex I of the Executive Order (“EO”), is below:

As President Trump instructed in his January 20 America First Trade Policy Memorandum, the Commerce Department, the Treasury Department, and the U.S. Trade Representative delivered a Report to the President on April 1 covering a wide range of trade issues, including, among others, reviews of steel and aluminum tariff exclusions, investigations on copper and lumber imports, assessments of U.S. trade agreements, and a review of the “de minimis” tariff exemptions for low-value shipments. On February 13, the President directed further review of “non-reciprocal trading practices.” In addition to providing the basis for the April 2 EO, this Report will likely influence the imposition of further tariffs, especially in the ongoing national security investigations on copper and lumber.

The Interaction of the Reciprocal Tariffs with Additional New Tariffs

In a separate but related action, so-called “secondary tariffs” of 25 percent may soon be imposed on imports from any country that the Commerce Department determines is importing oil from Venezuela. It is widely expected that China will be among the countries designated by Commerce. These tariffs will be in addition to all other tariffs already being imposed.

Finally, President Trump signed an EO on April 2 ending de minimis treatment on imports from China beginning May 2. Imports valued at $800 or less have until now been exempt from any tariffs. After that date, these imports will be subject to a duty of either 30 percent or $25 per item, increasing to $50 after June 1. This is in addition to all other tariffs and duties imposed on China thus far.

Are Any Goods Excluded from the Reciprocal Tariffs?

The EO confirmed that imports from Canada and Mexico, currently subject to 25 percent tariffs (10 percent for energy and potash) to address fentanyl and immigration border security issues will not be subject to reciprocal tariffs. However, goods that comply with the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (“USMCA”) preferential origin rules were and will continue to be exempted from the 25 percent and 10 percent fentanyl/migration tariffs. Should the President terminate the fentanyl/migration orders, Canadian and Mexican goods (with the exception of energy and potash) that are not compliant with the USMCA rules of origin will become subject to a 12 percent rate.

Another class of imports that will not be subject to the April 2 tariffs are items that are subject to the 25 percent tariffs that have previously been imposed under section 232 (an action that that allows the President to adjust imports if they are deemed to threaten national security) against a targeted range of goods, including aluminum, steel, and automobiles and their parts. Products that are currently subject to section 232 investigations, such as lumber and copper, and products that are expected to be investigated such as pharmaceuticals and semiconductors, are also excluded. Bullion, energy, and other certain minerals that are not available in the United States, as well as all other products enumerated in Annex II, are exempt.

Click here for President Trump’s reciprocal tariff EO (which includes Annexes I and II as in-text hyperlinks), and here for the accompanying fact sheet. Click here for President Trump’s April 2 amendment to the de minimis EO on China. Click here for the report to the president from Commerce, Treasury, and the United States Trade Representative.

‘Secondary’ Tariffs Target Countries Importing Venezuelan Oil

On March 24, President Donald Trump issued a new Executive Order that authorizes tariffs on countries importing Venezuelan oil. More specifically, starting on or after April 2, 2025, the U.S. may impose a 25 percent tariff on all goods imported into the U.S. from any country that imports Venezuelan oil, whether directly from Venezuela or indirectly through third parties. These tariffs would expire one year after the last date on which the country imported Venezuelan oil, or at an earlier date subject to U.S. government discretion.

For these purposes:

“Venezuelan oil” means crude oil or petroleum products extracted, refined, or exported from Venezuela, regardless of the nationality of the entity involved in the production or sale of such crude oil or petroleum products

“Indirectly” includes purchases of Venezuelan oil through intermediaries or third countries where the origin of the oil can reasonably be traced to Venezuela, as determined by the U.S. Secretary of Commerce

The Secretary of Commerce, with the U.S. Secretary of State and Attorney General, will determine whether a country has imported Venezuelan oil, directly or indirectly, and issue regulations to implement the order.

It is not yet clear which countries may be subject to tariffs under this Executive Order, but news reports suggest the Chinese government buys the largest amount of Venezuelan crude oil, followed by India and Spain, among others. Indeed, the Executive Order also provides that if the Secretary of State decides to impose tariffs under this order on China, the tariffs will also apply to Hong Kong and Macau to prevent transshipment and evasion.

Companies should prepare by evaluating their supply chain for suppliers located in countries dependent on Venezuelan oil. Companies should also review their import procedures (including tariff classification and country of origin) to prepare for additional potential tariffs.

If tariffs are imposed on China, they will also apply to Hong Kong and Macau to prevent transshipment and evasion.

www.whitehouse.gov/…

Auto Tariffs: Pumping the Brakes on Imports

On or after April 3, 2025, all foreign automobiles imported into the U.S. will be subject to a 25 percent tariff. The new auto tariff will be applied in addition to the general tariff rate of 2.5 percent, plus any applicable steel derivative tariff. President Donald Trump issued a proclamation implementing the new tariffs on March 26, based upon a 2019 report under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, which concluded that “automobiles and certain automobile parts are being imported into the United States in such quantities and under such circumstances as to threaten to impair the national security of the United States.”

The new auto tariffs will apply to automobiles from all countries. However, importers of autos that qualify for the tariff benefits of the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Free Trade Agreement (USMCA) will be permitted to subtract the value of the U.S. content of the autos from the full value of the vehicle for purposes of applying the 25 percent tariff.

The proclamation also provides that if U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) determines that the U.S. content has been overstated, the 25 percent tariff will be applied to the full value of the auto without any exclusion of U.S. content. The 25 percent tariff would be applied retroactively (from April 3 to the date of inaccurate overstatement) as well as prospectively. Thus, significant enforcement efforts by CBP are anticipated.

The proclamation also covers certain auto parts in a yet-to-be published Annex. Because the 2019 Section 232 report specifically identified imported engines and engine parts, transmissions and power train parts, and electrical components of vehicles as a threat, it is anticipated that such parts will be subject to the tariffs. Moreover, within 90 days, the proclamation requires the Secretary of Commerce to establish a process for adding additional parts to the Annex.

Today, only about half of the vehicles sold in the United States are manufactured domestically, a decline that jeopardizes our domestic industrial base and national security, and the United States’ share of worldwide automobile production has remained stagnant since the February 17, 2019, report.

www.whitehouse.gov/…

Buyer Beware: Trying to Avoid or Reduce Tariffs

As the typical tariffs on many goods from China have soared to at least 45 percent, some suppliers in China are offering U.S. purchasers a way of avoiding or reducing the tariffs. However, U.S. importers should carefully scrutinize such offers. Attempting to lower or avoid tariffs without the proper analysis and exercise of reasonable care could lead to enforcement actions by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and significant monetary penalties.

The reported proposal: Some suppliers in China are suggesting to their U.S. customers that the supplier issue an invoice for the imported goods not including engineering, patent licensing, setup, or other overhead costs of manufacturing the goods in China. The suppliers would then invoice the U.S. purchasers separately for those costs. That second invoice would not be sent with the shipped goods.

In other words, the declared, dutiable value of the goods would be lower than the total price actually paid by the U.S. importer to the foreign seller. The amount of duties, which are applied as a percentage of the dutiable value, would thus be lowered.

The problem with such a proposal:

1. Under the U.S. Customs valuation rules, the dutiable value (usually the “transaction value”) is generally the price paid or payable to the foreign seller. If certain pre-import costs such as design or engineering are not included in the price of the goods, those costs must be added to the price of the goods to calculate the dutiable value. All payments made to the foreign seller are presumed to be part of the dutiable value, and the U.S. importer of record bears the burden of overcoming this presumption. Thus, failure to include such costs in the dutiable value generally would be a violation of CBP regulations.

2. The U.S. importer of record bears all the liability for underpayments of duties to CBP and for fines and penalties applied as a result of the violation. Civil fines of an amount up to the domestic value of the imported merchandise can be imposed, and criminal penalties can also be imposed for knowing and willful violations. The foreign seller will have been paid by the U.S. purchaser and will not be responsible for what could be significant amounts owed to CBP.

3. Significant enforcement of tariff evasion on goods imported from China is anticipated, including initiation of False Claims Act cases by the Department of Justice. Furthermore, a presidential proclamation issued in February on additional steel and aluminum tariffs directs CBP to impose maximum penalties for misclassification of such products to evade tariffs.

Given all of these circumstances, U.S. importers should exercise caution when considering any tariff avoidance or reduction proposals offered by suppliers in China.