Cracking the Gardner Heist: Eight Clues to Unlocking the World’s Greatest Art Mystery.

Most art galleries and museums are renowned for their treasures, proudly showcasing priceless masterpieces. However, Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum has gained fame for what is no longer there. On the night of March 18, 1990, the museum fell victim to the largest art heist in history. Two men, disguised as police officers, subdued the guards and made off with 13 pieces of irreplaceable art valued at approximately $500 million. Decades later, the mystery remains unsolved, with the stolen masterpieces still missing. The heist has captivated art lovers, investigators, and conspiracy theorists alike, making it one of the most infamous crimes in cultural history.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

The Missing Masterpieces

The stolen collection includes some of the most renowned works in art history:

- Johannes Vermeer’s The Concert: A masterpiece by the Dutch painter, this work is among only 34 known Vermeer paintings in existence. It is considered the most valuable unrecovered painting in the world.

- Rembrandt’s The Storm on the Sea of Galilee: The artist’s only known seascape, depicting Christ and his disciples in a stormy boat.

- Rembrandt’s A Lady and Gentleman in Black: Another significant work by the Dutch master.

- Édouard Manet’s Chez Tortoni: A celebrated portrait showcasing Manet’s talent for intimate scenes.

- Five Edgar Degas sketches: Small works depicting horses and riders, showcasing the artist’s fascination with movement and equestrian themes.

- An ancient Chinese gu: A ceremonial vessel, adding an exotic element to the thieves’ haul.

- A bronze eagle finial: An odd choice, this ornament was taken from the top of a Napoleonic flag.

Together, these works represent a staggering loss to the art world, with their value and cultural significance immeasurable.

Has the storm on the sea of Galilee been found?

The Woman Behind the Museum

The museum owes its legacy to Isabella Stewart Gardner (1840–1924), a trailblazing philanthropist and art collector. Born into wealth, Gardner became a cultural icon in Boston, known for her bold personality and progressive values. She built the museum in 1903 to house her extraordinary collection, designing it to resemble a Venetian palace. Her will stipulated that the arrangement of the artworks remain unchanged and that nothing could be added or removed.

Gardner’s eccentricities extended to her public persona. She was known for her avant-garde fashion choices, including attending the Boston Symphony wearing a hat emblazoned with “Red Sox.” Her commitment to art and culture made her museum a landmark, and her directives have shaped its response to the heist. To honor her wishes, the museum continues to display the empty frames of the stolen works, symbolizing hope for their return.

The Investigation

The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum heist has confounded investigators for over three decades. The FBI initially suspected local criminals with ties to Boston’s underworld. Among the early suspects was Myles Connor, a notorious art thief who had previously stolen a Rembrandt from Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. However, Connor was in prison at the time of the heist, providing him with a solid alibi.

Another suspect was Brian McDevitt, who had attempted a similar heist in 1980, dressing as a FedEx driver to rob a museum in upstate New York. McDevitt later moved to Los Angeles, where he pitched a film script with striking similarities to the Gardner heist. Despite these leads, no arrests were made.

In 2013, the FBI announced that it had identified the thieves as members of a criminal organization based in the Mid-Atlantic and New England regions. The bureau suggested that the artworks had been moved through organized crime networks, but their current location remains unknown. Investigators also explored connections to the Corsican mob after reports surfaced of stolen paintings being offered for sale in France. The eagle finial, linked to Napoleon, added weight to this theory, as Corsica is Napoleon’s birthplace.

Despite these efforts, the case remains unsolved, and the whereabouts of the masterpieces are still a mystery.

An Inside Job?

One of the most debated theories surrounding the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum heist is the possibility of an inside job. This suspicion primarily stems from the actions of Rick Abath, one of the two security guards on duty during the robbery. Abath’s decisions that night—some of which blatantly violated protocol—have placed him under scrutiny for decades, even though he consistently denied involvement.

Rick Abath was a 23-year-old aspiring musician who worked as a night watchman at the museum. Described as disillusioned with his job and frequently critical of the museum’s operations, Abath’s demeanor raised eyebrows long before the heist occurred. He had previously expressed frustration over the low pay and lack of adequate security measures, calling attention to vulnerabilities that the thieves would later exploit.

Update: 900 Days Without Anabel: The Harrowing Tale of Spain’s Longest Missing Persons Case

On the night of the robbery, Abath’s actions were, at best, questionable. Around 12:30 a.m., approximately an hour before the thieves arrived, he briefly opened the museum’s side door. This move violated security protocol and was never fully explained. Abath claimed he opened the door to check if it was securely locked but failed to document the incident or inform his partner, Randy Hestand. This unusual action was later flagged by investigators as a potential signal to the thieves that the museum was accessible.

At 1:24 a.m., when the men disguised as police officers rang the buzzer at the side entrance, Abath allowed them entry. According to standard procedure, Abath should have verified their credentials or called the police department to confirm their story. Instead, he admitted them without hesitation, trusting their claim of investigating a disturbance. Critics argue that this decision, particularly in light of his earlier unauthorized opening of the door, indicates potential complicity.

Another oddity is the behavior of the museum’s motion detectors during the robbery. Infrared sensors tracked the movements of the thieves through the building, yet no activity was recorded in the Blue Room, where Manet’s Chez Tortoni was stolen. The only movements detected in that room were Abath’s during his patrol earlier that night. This discrepancy led investigators to question whether Abath could have removed the painting himself and staged its theft as part of the larger heist.

Chez Tortoni is a painting by the French artist Édouard Manet, painted ca. 1875.

When questioned by authorities, Abath denied any involvement in the crime. He admitted to making mistakes, such as opening the side door and neglecting to verify the identities of the supposed police officers, but he insisted these errors were due to naivety rather than collusion. Polygraph tests were inconclusive, and no physical evidence linked him to the thieves. However, his actions have fueled widespread speculation about his role—or lack thereof—in the heist.

Former FBI agent Bob Wittman, a leading expert on art theft, has repeatedly emphasized that insider involvement is common in such crimes. “About 89% of museum thefts involve some level of internal assistance,” Wittman explained in an interview. He noted that even unintentional acts, such as failing to follow protocol, can make security personnel unwitting accomplices.

The theory of an inside job is further complicated by the museum’s lax security policies at the time. Guards were paid slightly above minimum wage and received minimal training. The museum lacked interior surveillance cameras, relying solely on outdated infrared motion detectors and a single panic button at the security desk. These vulnerabilities made the institution an easy target for thieves, regardless of insider involvement.

Despite the suspicions surrounding Abath, no concrete evidence has ever been found to implicate him directly in the heist. In his later years, Abath expressed frustration over being repeatedly associated with the crime, maintaining that he was as much a victim as the museum itself. Nevertheless, his actions—both deliberate and accidental—remain one of the most enduring puzzles of the Gardner Museum robbery, ensuring that the question of an inside job lingers in the minds of investigators and the public alike.

Who were the suspects in the Gardner Museum Heist?

For over three decades, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum heist has stood as one of the most perplexing crimes in history. The theft of 13 masterpieces, valued at over $500 million, remains unsolved despite extensive investigations by law enforcement and private experts. With renewed public interest and emerging theories, Lawyer Monthly has undertaken a comprehensive review of the case, weighing the evidence, leads, and profiles of the most probable suspects.

Our analysis draws on available data, expert opinions, and patterns in similar crimes. Using a probability framework, we’ve assigned percentages to the likelihood of each major suspect or group’s involvement in the crime. This breakdown provides a fresh perspective on the most enduring questions surrounding the heist: Who carried it out, and why?

Here’s our list of suspects and their likelihood of involvement:

- Boston Mafia – 40%: A highly plausible theory, supported by the organized nature of the heist and potential use of the stolen art as leverage in criminal negotiations.

- Rick Abath (Security Guard) – 25%: An inside job remains a key consideration, with Abath’s behavior raising significant questions.

- Corsican Mob – 15%: Tied to the unusual theft of the Napoleonic eagle finial and reports of Gardner works surfacing in Europe.

- Myles Connor (Art Thief) – 10%: A legendary art thief with strong ties to similar crimes, though his incarceration at the time weakens his case.

- Brian McDevitt (Con Artist) – 5%: His similar heist attempt and suspicious behavior post-robbery warrant consideration but lack concrete links.

- Unknown Professional Thieves – 5%: The possibility of unidentified individuals pulling off the heist cannot be ruled out given the meticulous execution.

Unmasking the Gardner Heist: A Fresh Look at the Prime Suspects

Despite decades of investigation, the crime remains unsolved, and the stolen pieces—valued at over $500 million—are still missing. The empty frames of the stolen works hang in the museum to this day, a haunting reminder of the loss.

But who was behind this meticulously planned heist? Over the years, investigators have honed in on several suspects, from notorious art thieves to organized crime syndicates, and even the museum’s own staff. Each suspect brings a unique set of motivations and clues to the case, complicating efforts to pinpoint the masterminds. In this feature, we take a closer look at some of the most prominent suspects, evaluating the evidence and theories that link them to the greatest art theft in history.

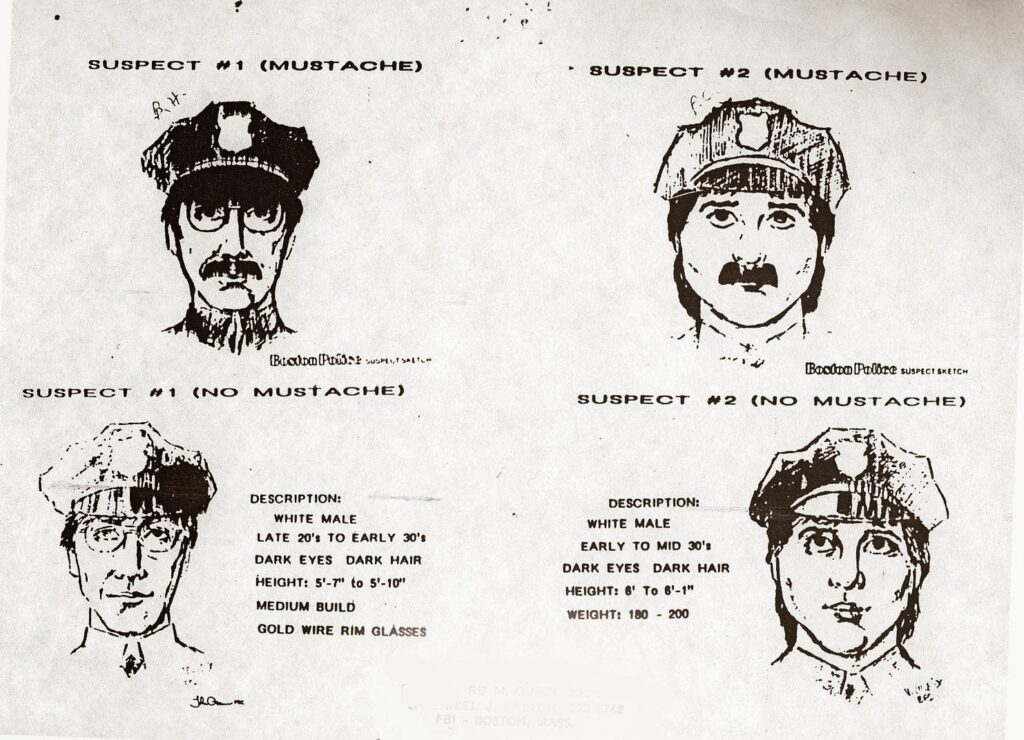

Police sketches of the thieves

Boston Mafia

The FBI’s primary theory centers on organized crime, particularly the Boston Mafia, which was active and embroiled in internal conflict during the late 1980s and early 1990s. The heist’s meticulous planning and execution suggest professional criminals with experience in high-stakes thefts.

The Boston Mafia was deeply involved in illegal enterprises, including art theft. Art is often used as collateral in drug and arms deals or to negotiate reduced prison sentences. Carmine “The Snake” Romano and Vincent Ferrara, mobsters with known ties to art theft, were investigated but not conclusively linked. Robert “Bobby” Donati, a Boston Mafia associate, was implicated in theories suggesting he orchestrated the theft to leverage the release of mob boss Vincent Ferrara. Donati’s murder in 1991 further fueled speculation.

Latest: Could Richard McCoy Jr. Be D.B. Cooper? New Evidence Could Solve the 1971 Hijacking Mystery

Organized crime’s infrastructure and motivations align with the nature of the heist. The mafia’s involvement is plausible, but identifying the specific individuals involved remains challenging due to the lack of physical evidence.

Myles Connor

A notorious art thief and career criminal, Myles Connor is often mentioned as a potential suspect. In 1975, Connor famously stole a Rembrandt from the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, using it to negotiate a lighter sentence. He had deep knowledge of art and security systems. Connor was in prison during the Gardner heist but claimed he may have helped plan it. He suggested that the thieves followed a blueprint he’d discussed years earlier. His background and reputation as a master thief make him a compelling suspect. Connor’s incarceration at the time of the heist eliminates him as a direct participant. However, his knowledge and network could have influenced the planning or inspired the crime.

Rick Abath (Security Guard)

Rick Abath, the night guard who allowed the disguised thieves into the museum, has been scrutinized for his actions and potential complicity. Abath violated protocol by opening the museum’s side door before the heist, allowing the thieves inside without verifying their identities. Motion sensors also showed that Chez Tortoni was removed from the Blue Room, but no activity was recorded there during the robbery—except for Abath’s earlier patrol. Abath has consistently denied involvement and passed polygraph tests, though some investigators remain unconvinced.

Latest: Who Killed JonBenét Ramsey? The Beauty Queen’s Tragic Death

Abath’s behavior raises red flags, but there is no concrete evidence linking him to the crime. If he was involved, it could point to an inside job, either through active participation or as an unwitting accomplice.

Brian McDevitt

Brian McDevitt, a con artist and aspiring screenwriter, attempted a similar heist in 1980, targeting a museum in upstate New York while disguised as a FedEx driver. McDevitt’s failed heist shared striking similarities with the Gardner robbery, including the use of disguises. After moving to Los Angeles, McDevitt pitched a film script eerily mirroring the Gardner heist, raising suspicions that it was a veiled confession. McDevitt’s past and fixation on the Gardner heist suggest he may have been involved or inspired by the crime. However, investigators have found no definitive link to place him at the scene.

Corsican Mob

A surprising lead emerged in the early 2000s, tying the heist to the Corsican mob, a criminal organization based on the Mediterranean island of Corsica. The theft of the bronze eagle finial, a Napoleonic artifact, aligns with Corsica’s connection to Napoleon, who was born on the island. This theory gained traction after reports of stolen Gardner artworks being offered for sale in France. Investigators pursued this lead in 2005, but the operation fell apart when the suspects were arrested for other stolen art.

Cultural Loss and Legacy

The theft was not only a financial loss but also a cultural tragedy. The stolen works represent some of the greatest achievements in Western art, and their absence leaves a void in the art world. For the Gardner Museum, the heist has become an inseparable part of its identity. The empty frames serve as a poignant reminder of what was lost and a symbol of resilience.

Is there still a reward for the Gardner Museum heist?

The museum continues to offer a $10 million reward for information leading to the recovery of the stolen works, the largest bounty ever offered by a private institution. Despite the passage of time, the search for these masterpieces endures, driven by the hope of restoring them to their rightful place.

Why It Still Matters

The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum heist remains one of the most compelling unsolved mysteries in the art world. Its mix of audacity, intrigue, and cultural significance has captured the imagination of generations. The case has inspired books, documentaries, and even Hollywood adaptations, highlighting its enduring allure.

As the art world waits for answers, the empty frames on the museum’s walls stand as a testament to the enduring power of art and the unyielding quest for justice. While the stolen masterpieces remain hidden, the hope for their recovery continues to inspire investigators and art lovers worldwide.

Cracking the Gardner Heist: Eight Paths to Solve the World’s Greatest Art Mystery

The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum heist remains one of history’s greatest art mysteries, but with a combination of new investigative methods and evolving circumstances, the case could one day be solved. Testimonies or confessions from living participants, associates, or family members could break the silence surrounding the crime, especially as time diminishes fears of reprisal or prosecution. Similarly, the role of organized crime networks and the potential for recovered items during raids or through whistleblowers remain promising avenues.

The art black market is another fertile ground for clues. As stolen pieces often resurface in attempts to sell them or as part of criminal negotiations, any renewed movement of the artworks could shed light on their whereabouts. Advances in technology, such as AI, enhanced forensic tools, and improved surveillance analysis, offer investigators new ways to reexamine decades-old evidence.

Public involvement could also lead to breakthroughs, whether through accidental discoveries in storage units or anonymous returns driven by media attention. Cold case reviews and new connections between past crimes and suspects could help map the intricate web of this heist.

By leveraging these eight factors, there is hope that this enduring mystery will one day be resolved, restoring the stolen masterpieces to their rightful place and closing a pivotal chapter in art history.