The recently released videos of Memphis police officers violently beating Tyre Nichols, a 29-year-old Black man, show how quickly a traffic stop—that police initially said was for reckless driving—led to officers ending Nichols’ life through their deadly actions. While the footage is shocking and disturbing, the police violence it captures is far from new. Researchers contend that more people were killed by U.S. police in 2022 than in any other year in the past decade.

At the Stanford Center for Racial Justice, we are researching the policies that govern when and how police are permitted to use force against the members of their communities. Our research is culminating in the development of a comprehensive Model Use of Force Policy that aims to reduce deadly encounters between police and the people they serve, while promoting law enforcement practices that will be fair, safe, and equitable for everyone.

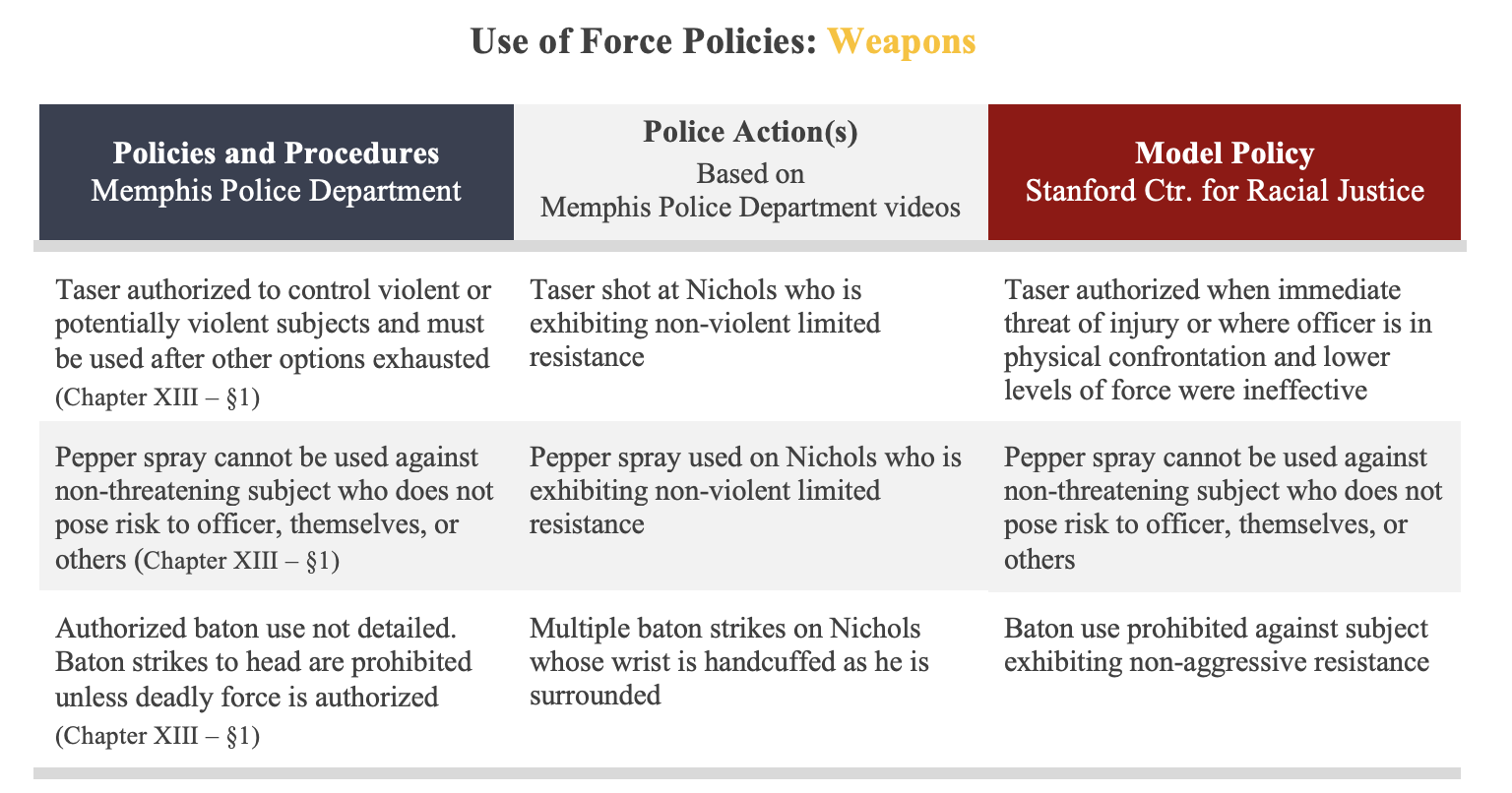

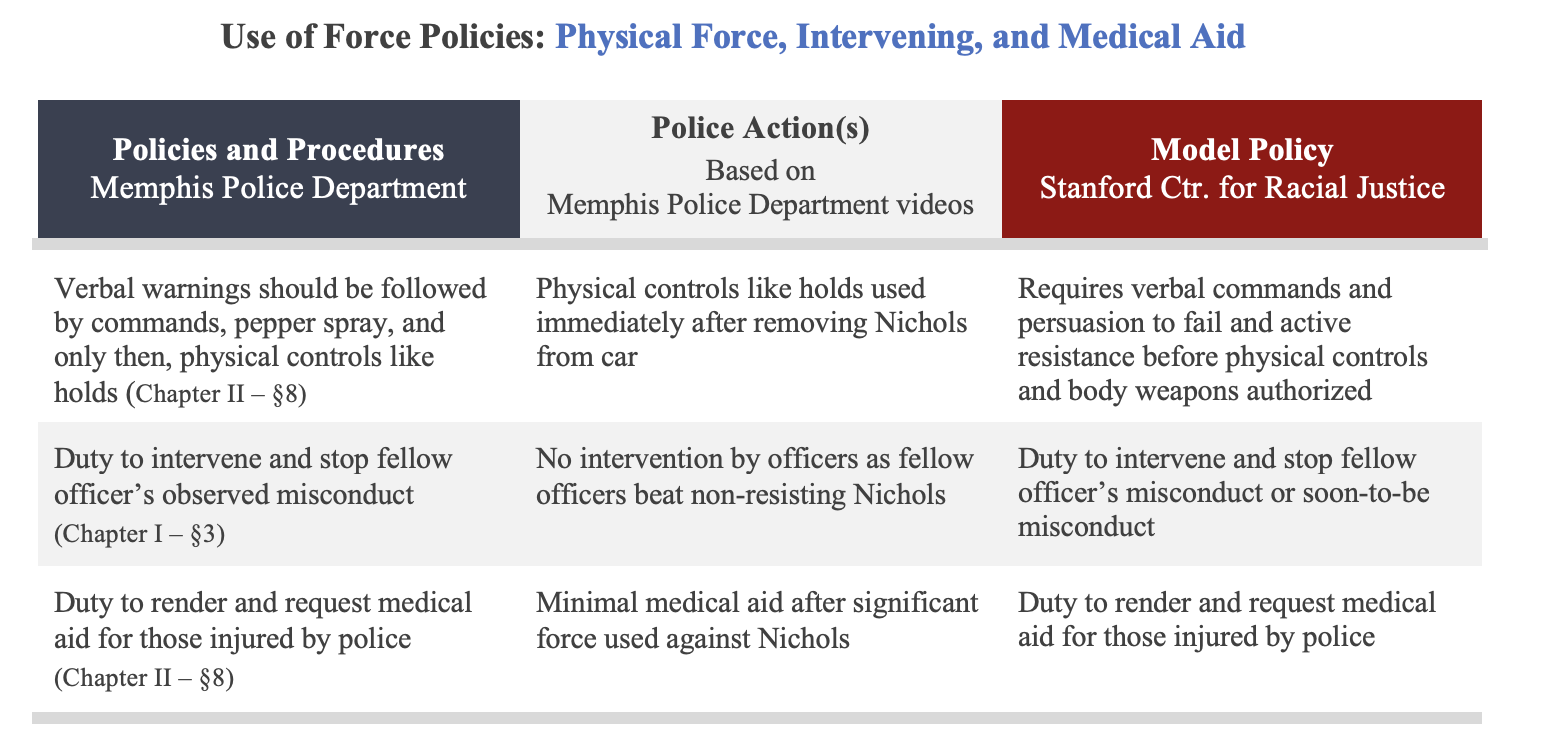

In this post, we have examined the actions of the Memphis officers, identified the Memphis Police Department’s corresponding policies on use of force—several of which were clearly violated by multiple officers—and compared those policies with the best practices in the beta release version of the Center’s Model Policy.

Read more: Memphis Police Department Policy and Procedure Manual, Chapter II – §8

There are several ways the Memphis use of force policies compare well with the Center’s Model Policy. Indeed, the Model Policy draws from Memphis’ principles on de-escalation and, like the Model Policy, Memphis’ policy sections on the duties to intervene and render aid create firm obligations for officers to stop harmful situations and get those injured by police the medical care they need. But there are also key ways the policies differ. The Model Policy requires officers to use de-escalation techniques, whereas the Memphis policy appears to only encourage their use. In discussing weapons like batons, the Memphis policy is light on how the weapons should be used while the Model Policy specifies that, for instance, an officer must be able to “articulate the facts and circumstances that justify each and every strike.” These differences demonstrate the need for communities and law enforcement leaders to scrutinize their existing policies and closely consider future policy language.

Read more: Memphis Police Department Policy and Procedure Manual, Chapter XIII – §1

The Memphis Police Department touted reforms in the wake of George Floyd’s 2020 killing—such as the incorporation of the 8 Can’t Wait campaign’s principles around de-escalation and a ban on no-knock warrants. However, the department’s “Response to Resistance” section of its policy manual—which focuses on use of force—remains largely unchanged from a version dated July 2017, except to reflect a 2021 Tennessee law prohibiting chokeholds. Despite the importance of use of force regulations, Memphis’ principal policies are tucked into a chapter of the department’s policy manual titled “Arrests Charges & Investigations” and a summary of the chapter’s contents does not mention the “Response to Resistance” section. If a use of force policy is difficult to find, police officers may be less likely to review and consult it, which could lead to more violations of the policy, not to mention the need for policy transparency with the public on critical issues like use of force.

As Nichols’ tragic death makes clear, policies alone are not enough to prevent police violence and are the first pieces in a series of legal and administrative frameworks that attempt to positively shape officer conduct. When an officer violates their department’s policy, this violation is rarely, in and of itself, a crime—even if the underlying action, like an assault, is a criminal offense. But, a clear violation of department policy typically means two things. First, the department will have stronger arguments for terminating the officer’s employment. In announcing the firing of five police officers involved in Nichols’ death, the Memphis Police Department cited the officers’ violations of multiple department policies including excessive use of force, the duty to intervene, and the duty to render aid.

Read more: Memphis Police Department Policy and Procedure Manual, Chapter I – §3 and Chapter II – §8

Second, a prosecutor and grand jury who believe the officer’s conduct to be criminal know that the officer-turned-defendant will struggle to mount a defense that is rooted in their conduct complying with the department’s policy and training, a defense that is often persuasive to juries. The formal determination of these policy violations by the Memphis Police Department likely contributed to the Shelby County District Attorney and grand jury’s ability to charge the officers with serious crimes—including second degree murder—just twenty days after the traffic stop. When these prosecutions move towards trial in the coming months, we should expect to see witnesses from within the department, as well as external experts, called to testify about the charged officers’ departures from established department policy on use of force.