Mark David Chapman: The Role of Mental Illness, Delusional Fantasies, and Missed Intervention in the Assassination of John Lennon

The murder of John Lennon by Mark David Chapman on December 8, 1980, shocked the world, leaving an indelible mark on history and celebrity culture. Chapman, a former fan, killed the famed singer-songwriter outside his New York City residence, claiming Lennon represented the “phoniness” he despised. In the aftermath, Chapman’s mental health was scrutinized as authorities, psychologists, and the public tried to understand what drove him to murder. By examining Chapman’s life, diagnoses, delusional fantasies, therapy sessions, and missed intervention opportunities, we can gain a clearer understanding of how mental illness, unresolved trauma, and unaddressed psychological issues escalated into obsession and violence.

Early Life and Psychological Struggles: The Roots of Alienation

From a young age, Chapman displayed signs of emotional instability and a growing sense of alienation. Born in Fort Worth, Texas, and later raised in Decatur, Georgia, Chapman grew up in a turbulent household marked by conflict and insecurity. His father, a staff sergeant in the Air Force, was described by Chapman as emotionally unloving and often physically abusive toward his mother, creating an atmosphere of fear in the home. The volatile environment led to a lack of security and nurturance for Chapman, who often felt isolated, misunderstood, and unworthy of affection.

This emotionally deprived environment had a profound impact on his psyche, instilling a deep sense of inadequacy and insecurity that would follow him throughout his life. Lacking the stability and support a child needs, Chapman’s self-esteem suffered, leaving him vulnerable to emotional struggles as he moved through adolescence. After his family moved to Decatur, Chapman attended Columbia High School, where he experienced intense bullying. Due to his lack of athleticism and his introverted demeanor, he became a frequent target of his peers. Other boys called him derogatory names like “Pussy,” further wounding his fragile self-esteem and exacerbating his feelings of inadequacy.

This relentless bullying led Chapman to retreat further into his mind, constructing elaborate fantasies to cope with his reality. One of these fantasies involved a group of “little people” who lived in the walls of his bedroom, over whom he imagined having god-like control. These “little people” became Chapman’s coping mechanism, giving him a sense of power that he felt was missing from his actual life. In this fantasy world, he could command and protect his imaginary subjects, offering him an escape from the harshness of his home life and the torment he faced at school. This early retreat into fantasy marked the beginning of Chapman’s long history of escapist delusions and helped lay the groundwork for his later obsessions and deteriorating mental health.

By the time he reached adulthood, Chapman’s self-image was fractured. He struggled with an intense need for external validation, which would later manifest in his fixation on public figures like John Lennon. Without a strong support network or a healthy sense of identity, Chapman found solace in his fantasies and developed a black-and-white view of the world—a perspective that would shape his interactions, perceptions, and eventual descent into obsession and violence.

Therapy, Diagnoses, and Missed Red Flags

Chapman’s mental health challenges became more apparent in his early 20s when he began seeking therapy to understand his erratic emotions and emerging obsessions. During his therapy sessions, he revealed feelings of inadequacy, fantasies of fame and heroism, and a deep-rooted fixation on individuals he both admired and resented. Diagnosed with schizophrenia and borderline personality disorder, he exhibited symptoms such as auditory hallucinations, paranoia, and emotional instability. These conditions created a fertile ground for Chapman’s obsessive tendencies, particularly his black-and-white thinking, which led him to idolize figures like Lennon only to later view them as symbols of betrayal.

Despite these signs, Chapman’s therapists failed to recognize the severity of his condition. His therapy was sporadic, and he often abandoned sessions without follow-up. His symptoms were frequently downplayed as expressions of insecurity rather than indicators of serious mental illness, resulting in fragmented treatment that left him vulnerable to worsening delusions and paranoia. His fixation on Lennon, when expressed in therapy, was not flagged as a high-risk obsession, leaving a critical opportunity for intervention unexplored.

Fantasy of Moral Purity and The Catcher in the Rye

One of the most telling signs of Chapman’s deteriorating mental health was his fixation on J.D. Salinger’s novel The Catcher in the Rye. Chapman identified intensely with the protagonist, Holden Caulfield, who views himself as a protector against the “phoniness” of society. Chapman saw himself as a real-life “catcher” whose mission was to shield society from hypocrisy and insincerity.

In John Lennon, Chapman saw the ultimate “phony.” He perceived Lennon’s wealth and fame as contradictions to the ideals of peace and love that the musician promoted. This contradiction intensified Chapman’s anger, as he felt Lennon’s lifestyle betrayed the values he claimed to uphold. Chapman’s fantasy of moral purity turned into a delusional belief that he was on a righteous crusade against hypocrisy, with Lennon as his prime target. This sense of moral duty fueled his fixation, convincing him that his actions would serve a higher purpose. His attachment to The Catcher in the Rye became more than just an obsession; it was a moral justification that allowed him to rationalize his growing hostility toward Lennon.

Heroic Fantasy of Fame and Recognition

Chapman’s fantasies extended beyond moral purity; he also harbored a deep desire for fame and recognition. He had long felt insignificant and worthless, and his need for validation manifested in fantasies of achieving greatness. Chapman began to believe that by killing Lennon, he could escape his own obscurity and achieve lasting fame. The idea of being remembered, of “being somebody,” became a powerful motivator that pushed him toward violence. For Chapman, killing a globally revered figure like Lennon would grant him the notoriety he craved, allowing him to finally feel seen and important.

These fantasies of fame were tied to his feelings of inferiority and resentment toward successful public figures. Lennon’s fame, which Chapman both admired and resented, embodied everything Chapman felt he lacked. In his mind, eliminating Lennon would elevate him, transforming him from a “nobody” into someone worthy of public recognition. This twisted logic illustrates how his self-loathing and desire for validation fueled his obsession, shaping his delusions into a plan for notoriety.

Fantasy of Transformation and Redemption

In addition to fame, Chapman nurtured a fantasy of personal transformation. He saw the act of killing Lennon as a way to undergo a profound change, almost as if the murder would cleanse him of his insecurities and feelings of failure. He believed that taking Lennon’s life would give him purpose and direction, filling the emotional void he had long felt. This idea of transformation was a powerful motivator, as it represented an escape from the inadequacies that had plagued him for so long.

In his mind, the murder would be a transformative act, one that would grant him a sense of fulfillment and inner peace that had eluded him throughout his life. This belief highlights the extent to which Chapman’s mental illness shaped his reality, as he projected his desire for redemption onto a violent, delusional plan.

Paranoid Fantasy of a Predestined Mission

As Chapman’s mental health deteriorated, he experienced hallucinations and reported hearing voices that urged him to kill Lennon. He began to feel as though he were on a predestined mission, a divine or moral imperative he was meant to fulfill. These hallucinations, which likely stemmed from his schizophrenia, intensified his sense of purpose and added a layer of inevitability to his plans. Chapman’s paranoid delusions created a sense of predestination, convincing him that he had no choice but to carry out the murder.

This perceived predestination removed any feelings of doubt or guilt, as Chapman believed he was fulfilling a duty imposed upon him by forces beyond his control. His paranoid fantasy of a mission contributed to his sense of self-importance and moral righteousness, fueling his fixation on Lennon and justifying his violent intentions.

The Assassination of John Lennon and Chapman’s Psychological State

On December 8, 1980, Mark David Chapman arrived at the Dakota, the New York City residence of John Lennon, carrying with him a copy of The Catcher in the Rye signed with the chilling words, “This is my statement.” Chapman had planned this day meticulously, rehearsing the encounter in his mind, driven by a twisted combination of hatred, admiration, and a delusional sense of mission. The act itself, and Chapman’s mental state before, during, and after the murder, reflected the deeply fractured psyche of a man whose untreated mental illness, delusional fantasies, and distorted sense of purpose had reached a crisis point.

Earlier that day, Chapman had approached Lennon for an autograph on a record, which Lennon, known for his openness with fans, kindly obliged. This initial encounter was brief and uneventful, yet it left a powerful impression on Chapman. Later, he would recall the surreal experience of standing close to his idol, the man he had both adored and condemned. Despite his growing hostility and delusions, Chapman felt momentarily awestruck by Lennon’s presence. This inner conflict—part of him idolizing Lennon, the other condemning him as a hypocrite—was evident throughout the day and would later surface in Chapman’s description of the murder.

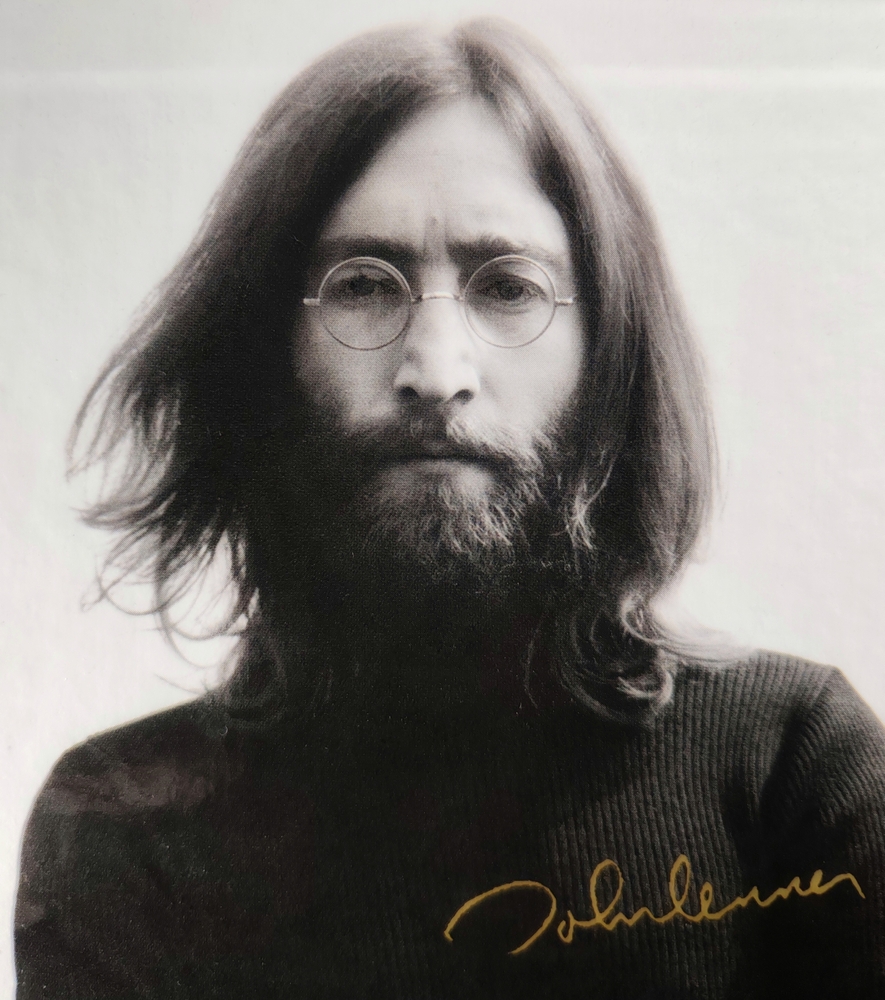

John Lennon

Chapman spent hours standing outside the Dakota, wrestling with his intentions. His internal struggle was evident; on one hand, he felt a moral imperative to carry out what he saw as his mission to eliminate a “phony.” On the other, he experienced a strong pull of admiration and even empathy for Lennon. In interviews, Chapman has reflected on this emotional turbulence, describing how he alternated between leaving the scene and remaining committed to his plan. His mind was divided, a battle between his delusional sense of duty and the residual admiration he had for Lennon, who had profoundly influenced him as a young man.

As the day wore on, Chapman’s sense of predestination and his delusions gained the upper hand. His fixation on The Catcher in the Rye as his “moral compass” convinced him that he was fulfilling a role similar to Holden Caulfield’s, protecting society from an individual he deemed fraudulent. In his mind, Lennon’s fame and wealth contradicted the ideals of peace and love he promoted, rendering him, in Chapman’s eyes, an ultimate “phony.” This belief formed the core of Chapman’s delusional fantasy, allowing him to rationalize his plan as a necessary act of moral correction.

Related: Charles Manson: The Dark Influence Behind The Manson Family Murders

When Lennon and his wife, Yoko Ono, returned to the Dakota around 10:50 p.m., Chapman was waiting. As Lennon walked past, Chapman pulled out a .38 revolver and fired five shots, four of which hit Lennon in the back and shoulder. Lennon staggered into the Dakota’s entryway, collapsing from his injuries. Chapman, meanwhile, remained at the scene, calmly setting his gun down and pulling out his copy of The Catcher in the Rye, opening it and reading as he waited for the police to arrive. Witnesses described his demeanor as eerily calm and detached, an unsettling contrast to the violence he had just committed.

This detachment, often associated with dissociative episodes in individuals with severe mental illness, underscored the profound disconnection between Chapman’s actions and his awareness of their consequences. He later described feeling as though he were watching himself from outside his body during the shooting, a phenomenon common among individuals experiencing dissociation. This psychological detachment allowed him to separate himself from the brutality of his actions, reinforcing his delusion that he was fulfilling a “higher” purpose.

In the immediate aftermath of the murder, Chapman’s actions baffled both the public and law enforcement. When police arrived, he made no attempt to flee or resist arrest. Instead, he confessed to the crime on the spot, stating that he had done it because he believed Lennon was a “phony.” His calmness in the face of such a heinous act left many questioning his mental state. Even as he was handcuffed and taken into custody, Chapman appeared detached, immersed in his book, a stark image of a man who had fully succumbed to his delusional beliefs.

During his initial court appearances, Chapman’s mental state continued to reveal his profound psychological conflict. He openly expressed remorse at times, while at other moments he spoke of his actions as if they were necessary and justified. This inconsistency reflected his ongoing struggle to reconcile his original delusional purpose with the reality of having taken a life. To the public, he appeared as both a remorseful criminal and a man still clinging to his sense of mission. In one particularly haunting moment, Chapman read aloud from The Catcher in the Rye in court, reaffirming his attachment to the book as a moral guide.

Over time, Chapman began to understand the enormity of his crime, yet his reflections have remained complex and sometimes contradictory. In various parole hearings, Chapman has expressed deep regret, stating that he was “sorry” for what he had done and that he wishes he could take it back. However, he has also reiterated that at the time, he believed he was fulfilling a duty, illustrating the enduring hold of his delusional thinking even in the years following his incarceration.

Chapman’s mental state in the days and months after the murder provides insight into the powerful grip of his untreated mental illness. Diagnosed with schizophrenia and borderline personality disorder, he exhibited signs of both severe paranoia and deep-seated feelings of inadequacy. His borderline traits, marked by extreme black-and-white thinking, had caused him to shift from adoring Lennon to despising him, unable to accept the contradictions he perceived in Lennon’s persona. Meanwhile, his schizophrenia contributed to the auditory hallucinations and paranoid delusions that framed his crime as a predestined act.

Psychologists assessing Chapman in prison noted the persistence of his delusional beliefs and his identification with The Catcher in the Rye long after the murder. Although he has claimed to understand the gravity of his actions, Chapman has struggled to separate himself entirely from the mindset that led to the murder. This ongoing struggle highlights the complexities of mental illness and the challenges of fully overcoming deeply ingrained delusions.

The Impact of Missed Mental Health Interventions and Evolving Standards of Care

Mark David Chapman’s tragic decision to end John Lennon’s life is often examined through a psychological lens, raising questions about whether missed mental health diagnoses and intervention failures played a role. Although no legal actions were ever taken against mental health professionals or institutions tied to his case, Chapman’s history presents a compelling example of the potential ramifications of untreated mental illness. From an early age, Chapman exhibited troubling symptoms—detachment, violent fantasies, and delusional behavior—that might today prompt intervention from mental health professionals.

However, these signs went largely unaddressed. While Chapman did receive limited mental health support in his early years, it was neither sustained nor sufficient, leaving his underlying issues unchecked. Given the lack of extensive documentation on Chapman’s early mental health evaluations, it’s unclear whether his condition could have been diagnosed accurately at the time. Still, the absence of consistent support or intervention highlights the missed opportunity for potentially mitigating the escalation of his violent tendencies. Had there been a robust framework for recognizing and treating individuals with serious psychological symptoms, it is conceivable that Chapman’s behavior might have been redirected or managed.

In similar cases today, mental health professionals could face negligence claims if they failed to identify or properly address a patient’s violent tendencies, particularly if such failures directly contributed to harm. Standards of care for mental health have evolved since Chapman’s era, with far greater awareness of conditions like schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and other complex psychological disorders that can lead to delusional thinking or violent behavior if left untreated.

In Chapman’s case, however, it appears that his interactions with mental health providers were brief and sporadic, making it difficult to establish clear legal grounds for accountability. Legally, mental health professionals today are held to standards that require them to take preventive action if a patient poses a credible threat to themselves or others. This duty of care includes alerting authorities or placing patients under watch, steps that could, in theory, prevent tragedies like Chapman’s crime.

Chapman’s case also reflects systemic issues in mental health support from that era, particularly the lack of resources, limited understanding, and reluctance to treat patients with complex needs. Many individuals, especially during Chapman’s formative years, slipped through the cracks in a mental healthcare system that was not equipped to handle cases like his. Although these factors do not translate directly into legal liability, they underscore the critical need for a robust mental health infrastructure, one that can identify at-risk individuals and offer effective intervention.

Today, there are stronger mechanisms in place for evaluating individuals displaying psychological distress, including an emphasis on early intervention and treatment plans for those with violent ideations or delusions. Legal standards have progressed, partly due to cases where failures in mental healthcare resulted in public harm, prompting a change in how professionals are trained to respond to at-risk patients. For instance, duty-to-warn statutes now mandate that providers report credible threats of violence to law enforcement or intended victims, which was less rigorously enforced during Chapman’s time.

Chapman’s story highlights the importance of such legal and healthcare shifts. While no single diagnosis or specific intervention could guarantee the prevention of violence, the broad improvements in mental healthcare standards raise awareness about how early diagnosis and intervention can mitigate potential risks.

You Might Like: Carlos the Jackal: The World’s Most Wanted Revolutionary—Terror, Espionage, and the Cold War’s Greatest Villain

The lack of direct legal repercussions in Chapman’s case speaks to the limited awareness and capabilities of the time, but it also serves as a reminder of the transformative role that mental healthcare plays in public safety. By providing structured care and establishing legal mandates to act on credible threats, today’s systems aim to reduce the risk of tragic outcomes. In examining Chapman’s case through this lens, we gain insight into the ways in which legal and medical institutions have adapted to address the needs of those with untreated mental illness, underscoring the necessity of continuous improvement in both fields.